Conversations On Everything: Interviews Fall 2020

If Images Could Speak

“I’m interested in where language fails us, where it restricts a capacity of knowing and being in the world.”

In this article, use of the word “language” is in specific reference to written or spoken language.

Language is a collection of visual symbols and aural representations of thought, objects, interactions, and more. We use language to communicate with one another—to describe our worlds, explore questions, empathize, remember, and share stories. It is an integral part of existence, of how we excel in technologies, theories, and the arts. But I’m interested in where language fails us, where it restricts a capacity of knowing and being in the world. I imagine at one point in time, long ago, language was created as it applied directly to experience. What was experienced came first, then we applied words to represent that experience. Is it possible that now, so long after it was created, language limits our experiences through defining what experience is for us? For example: we think of a word, then we visualize what it means. Does that visualization, or that attachment to what we know the word to mean, color the actual experience of a thing?

And does language create particular categories or boundaries that limit us in true experience? Let’s take any study of science as another example. Any person, plant, object, or thing that is being tested and studied, usually has a layperson term. Then, the person, plant, object, or thing that is being studied gets a scientific name. The studied object gets put into a category with other things that are similar to it. That group gets a name too. Then, that group gets dissected further into other groups, which all receive their own labels. The pattern continues on and on infinitely. It makes me wonder—if someone is studying lilies, how far do they have to go until they don’t recognize what lilies are anymore? Lilies are no longer just lilies. Lilies are Lilium of the Liliaceae Genus, order: Liliales, higher classification: Lilieae.

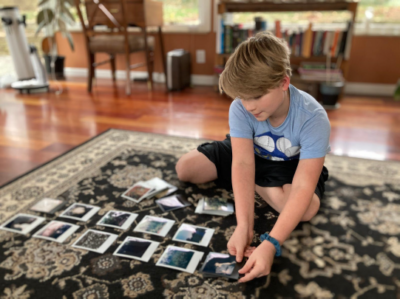

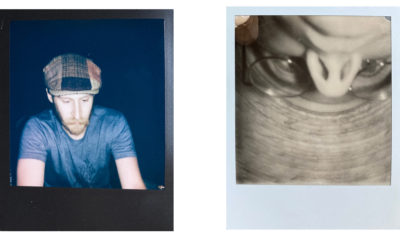

For me, this connects to experiential knowledge versus read knowledge, to presence. Do you lose some part of knowing something when you add the boundary of language? Language extends our knowing, but where does it retract it? To explore this idea further, my 10-year-old son and I played a call and response game using Polaroid photos. I had taken these Polaroids earlier this year. Similar to worded language, boundaries were created through the limitation of the images that were provided. In an interview-like form, Adrian chose an image from the stack of photos to pose a call or a question. In turn, I responded to Adrian’s question by matching a photo from the stack of Polaroids to his chosen photo.

Outcome: Adrian and I set the photos side by side in groups of two. We didn’t discuss what we were trying to communicate through the photos. We discussed other things going on in our lives, like current events of our neighborhood. By not discussing our choices of the photographs, it allowed automatic responses that weren’t clouded or predefined due to knowing by verbal language what we were thinking. There were a number of ways to approach the meaning or response to a photograph. You could try to get an overall feel for the photo based on shapes and colors. You could also reference the subject matter of the photograph directly, whether a plant, person, animal, or object. Much of what was communicated between Adrian and I through the photo-based interview was dependent on our shared knowledge and historical experience.

As a reader of the interview, you will be met with the limitation of being unable to fully define the exchange between Adrian and I. I invite you to bring your own histories and knowledge as you look at the images and interpret the interview.

Adrian’s questions are on the left and my responses are on the right:

Adrian Rosser (b. 2010) is a 5th grader at Wilson Hill Elementary. His favorite color is purple and he likes folk music. Adrian enjoys playing video games like Zelda. He is an avid reader with a big voice. His voice is often heard throughout his home from his singing. Adrian recently joined the school orchestra. He is learning to play the violin. Currently, he misses his friends due to COVID and is working hard on his schoolwork through the Ohio Online Learning Platform, even though he doesn’t like it.

Rebecca Copper (b. 1989) reflects on her lived experiences through art projects that range from socially engaged art to modes of individual creation through film photography and video. Rebecca is interested in the different ways of knowing, experiential knowledge, and how people are influenced in mediated ways. She works through themes such as: phenomenology, intersectional feminist politics, American education, and institutions of care. She is currently an MFA candidate through Portland State University’s Contemporary Art Practice, Art and Social Practice Program. Recently, she worked as a research assistant for the Art and Social Practice Archive which is housed within PSU’s special collections and finished a fellowship with the Columbus Printed Arts Center in Columbus, Ohio.

Cultivating Community

“We think of our social practice of working with people partly as just running the studio space, working with artists, trying to create platforms that are for artists… That’s one way we kind of work-through almost treating arts administration as a social practice.”

I decided to interview the founders of Sunset Art Studios because they provided support to reframe my existing practice into a social practice through their Artist Residency Program. Prior to participating in the residency, my understanding of social practice was limited. My work had participatory elements such as community engagement; I was unknowingly working in the social practice realm. Sunset Art Studios provided a space and resources to expand my understanding of social practice and how it related to my work. The interview was conducted via Zoom on a Saturday afternoon.

Kiara Walls: Hello, I’m really excited to be interviewing with you today. My first question is, how did Rachel and Emily meet?

Emily Riggert: Well, we met working at an arts co-op collective here in Dallas called Oil and Cotton, and we were some of their first employees, interns and stuff like that. We overlapped a couple of times working there and I think we first met briefly and maybe 2013, but then finally met and worked together in 2015 for the first time. Awesome. Awesome. Awesome. Yeah. And then I had this crazy idea because I was so frustrated that I didn’t have studio space. And I think Emily, you were also frustrated because you had just gotten out of school and I was like, what if we just made it, it doesn’t exist. Let’s just make it ourselves. That’s how it began.

Kiara: Awesome. Okay. What you’re referring to is Sunset Art Studios. Yeah. Okay, cool. What is it like to be a part of an artist pair?

Emily: Well for me it feels like we’re kind of two sides of the same coin, where we each bring a part to the process—the creative process that maybe wouldn’t be there without the other, or we have different strengths that play off of one another. For me, Rachel always is bringing in new inspiration and new ideas, and then I follow up with logistics, how to make the ideas happen. I think it’s great because if we’re working on our own, you know, we have our own strengths, but then also areas where our own processes can kind of, at least for me, stall out. So it’s nice to have a partner in the process with me as I move through ideas.

And then I think for me, it’s been working; I don’t know that every partnership works this way, but it’s been really amazing for me to have a working partnership with someone who I know from all of our conversations. Just from the time that we’ve worked together, we have some really specific shared goals. And even if they’re not quite exactly the same, the goals that we do have for ourselves and for our arts practice and even just what we think art should be and do are similar enough that we can support each other through that collaborative effort to realize.

Rachel: This joint vision. And I think that probably to me the most fulfilling part of working in a partnership is having that— having that support for my ideas, but also being able to support someone else with their ideas and then working together to bring those things to fruition. I think that has been totally huge and kind of propels me forward in the stuff that I want to work on. That’s just me, that’s just my personal practice.

Kiara: Hmm. Nice. Can you both talk about your individual practices also?

Rachel: My background is in photography. That was my BFA and my MFA and all of the certificates or whatever. I came to art from this very sort of observational angle that photography has. And then over time realized that I became- I was becoming more and more interested in creating something and building something that was a little more tangible. I think photography was a really great foundation for me, from where I am now, because it helped me think really critically about the world that I’m seeing and to think critically about the images that I’m taking in and the messages that I’m taking in. Helping me figure out how I actually want to respond to those ideas?

So now in a lot of my individual practice, I actually work a lot with appropriated images. Most of them or pretty much all of them are either discarded, abandoned images, images from archives, a lot of public images. Some of my most recent projects have been things like family—my own family archive is something that I’m still kind of working through and figuring out how I want to respond to those types of images. I’ve done projects recently that were using the USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab and they photograph different kinds of bees and related insects. I also did a project a couple of years ago that sort of combed through a lot of satellite imagery of earth, but also of other constellations and planets and things like that. That was thinking a lot about the direction of looking, looking down, looking out and how those two perspectives can kind of blend and fuse together in different ways.

So I think a lot about images and about messaging already and through the image side of things, I tend to like to start an image and then that becomes usually some kind of installation or intervention or something like that. So there’s thing where the image is almost how I’m trying to work through the idea. And then the final outcome is usually something that’s interactive or people can move through it, move through an entire space or something like that.

Emily: Well, for me, I come from a non-disciplinary background. I never chose a certain thing to focus on. And so as a result my art making practice can look like a lot of different things, and also a lot of different things kind of pulled all together. I’m a little bit, I guess the word is multi-disciplinary, and a lot of my work centered around the idea of the home and the female within it. What that looks like can be kind of assemblage sculptures. I do a lot of work with materials that are kind of process heavy. So woodworking and then woodblock printing ceramics, and then pulling all of those things together to make what are basically relief sculptures, still things that you can hang on the wall, but things that kind of blur the line between, is this something that is home decoration, is this artwork, and then thinking about my home as my art making environment, and then also turning my art making environment into a place that resembles the home. So when I set up my own studio at sunset, the first thing I said to myself in alpha at original, I was like, well, it needs to look like the living room. So kind of blurring those lines between art making space and living space.

Kiara: Nice, nice. It sounds like both of your practices pull from a conceptual understanding of things, and that’s really interesting that you incorporated that into the actual studio space for Sunset Art Studios. My next question is if you had to explain the concept of socially engaged art to a family member using one sentence, what would you say?

Emily: This is great because oftentimes when we write grants, we have to think about the grant committee not specifically being involved in a conceptual social practice. So my job during the process is always to get it down to like one or ten sentences. Here’s my sentence: If painters use paint as their medium, social practice artist use engagement with the public as their medium.

Kiara: Nice, that’s a really good explanation. Okay, so your nonprofit is called Sunset Art Studios. What inspired that name?

Rachel: We applied for funding from a local Dallas-Fort Worth sort of consortium or network of galleries that do this really cool program, where everybody has a big fundraiser night and local emerging artists that meet certain criteria all put forth their ideas. The night of is kind of oddly American Idol-ish, like everybody gets on stage and gives an exactly six minute presentation and has to convince the audience of the dinner to vote for them and why their project has to happen. And so I think from the very beginning, that was actually really useful for what we do at Sunset Art Studios, because any project we work on, we sort of automatically have to think, why should this exist? And how do I convince someone else to get onto this train with me? Sorry, repeat the question for me again. I got lost.

Kiara: No worries. What inspired the name Sunset Art Studios?

Rachel: Yes, So when we were working on this idea, I kind of took this concept of wanting… We didn’t really know that we were going to make a social practice studio space; that language came to us later. But in the beginning we knew that we wanted to create a space for artists and the public to connect in a really intimate and approachable way. Part of that came from the desire to be embedded in the local community. We both live and have worked in Oak Cliff for over ten years. So we knew we wanted to be in this neighborhood. In a part of Oak Cliff, there’s this history of old train systems in Dallas and the timeline of how Oak Cliff became incorporated into the major city of Dallas and stuff like that. Part of that history includes a streetcar line that ran through the neighborhood, where we were originally going to try to get our studio. And if you go around Oak Cliff, you see businesses named sunset such-and-such all over the place. There’s like Sunset High School, there’s Sunset Chiropractic. So it’s a name that is sort of embedded in an almost subconscious way into this whole area. And knowing that and understanding the streetcar line as this destination that met people where they were, I think was really significant. And so even though we didn’t land in that location where the streetcar was, we landed on that name as something that was really meaningful to us, had a lot of history built into it and was already meaningful for the community that we wanted to work with.

Kiara: You know, I never knew the inspiration behind your name, but just hearing all of that is really awesome. So my next question was going to be, why did you choose to plant roots in that particular community within Dallas? You touched on that, but do you want to go a little bit more into it?

Emily: So Dallas is like the larger Metro, like the metroplex area where we live, but then within it, there’s neighborhoods that have names, and the neighborhood name is Oak Cliff. But then within that Oak Cliff actually has, uh, I used to know how many, I think it’s eight or ten different zip codes within Oak Cliff. And it used to actually be part of the city, or a separate part of Dallas. It was like Oak Cliff, Texas, way back. So the neighborhood we’re in is called Elmwood and Elmwood is kind of like right in the center of the entire Oak cliff area. And we found a spot—kind of the first place we were looking at was like a strip of office building or just a small block of commercial space within the neighborhood, and you’ll see areas of Oak Cliff and we found another one in Elmwood. There’s like downtown Elmwood, and it’s just a small street maybe; when you’re driving down it’s maybe six blocks long, and then within those are restaurants, car garages, an art studio, a barbershop, a dog park.

So we landed in downtown Elmwood, kind of at a time when the space wasn’t being used in a way. I don’t know if people were thinking about it as a destination space beyond like, Oh, this is where I go to the convenience store. This is where, you know, there’s a school close by. It had kind of gotten forgotten by the city, you know; there were no street lamps, there were no crosswalks, so just public space. The neighborhood association surrounding us has recently begun to do things like put in crosswalks and street plants and things like that. So it has more visibility as a meeting place.

Kiara: Nice. That goes into my next question. What are some of the ways you empower or revitalize the community through your practice?

Rachel: Kind of one thing that we do, one way that we work as a studio, is we think of our social practice of working with people partly as just running the studio space, working with artists, trying to create platforms that are for artists that might have resources, but they haven’t had access to those resources for whatever reason, usually because of being a part of some marginalized group that doesn’t already have built in platforms for them. That’s one way we kind of work—through, sort of, almost treating arts administration as a social practice, right.

Another way that we work is separated from that sort of administration side of things, and is thinking about space and access to space very broadly, and that administration stuff feeds or feeds from that idea of thinking about access to space, but separate from that is also, we think a lot about public space and who has access to it and how it’s planned and visualized. And so aside from the things we do inside the studio is that we think a lot about what’s called placemaking. But we also like to think of it as place keeping, because placemaking sort of through its language implies that nothing existed there before—there was no place—and being in the kind of location we are, where we’re in a neighborhood, we’re in a community that has been around for over a hundred years. That’s just not applicable to where we are. So we have to think we’re not making something new, but we can use our skills and our training and our tools that we have to honor and respect, and then celebrate and bring to light things that are already here, that might have been forgotten that might be, like Emily was saying, neglected by the city. We’ve worked with other organizations and partnered with them to do things like promote what seems like simple things like…responsible dog ownership, because our area has an issue with loose dogs or thinking about access to public parks space. What does that look like? And who’s encouraged to use that space depending on how the space is designed? So those are the two things that we think about when we’re thinking about this, the geographic place that we’re in.

Kiara: Nice. It also sounds like you are practicing transparency too, with the community, as far as dog ownership and accessibility to parks and public spaces, things like that, which is great. Can you talk a little bit about the artists that you have within this space? What’s the process like as far as choosing the artists that you have in your space?

Emily: Well, there’s kind of two to three different ways that an artist can interact with Sunset. The first and kind of cornerstone program that we have is our residency program. And the year we began, we always knew we wanted to have a rotating cast of artists who came through and the residency program has an application process. And part of the question is on processes: How do you expect to engage the public during your time at the studio? So we’re looking for projects where artists have in their mind engagement as a piece of their project. And even if they don’t initially have a concrete idea of engagement, but are interested in it, we’ve worked with different artists who kind of take an overview of what their process is and figure out ways that we can come up with ideas together to engage the public. Now, there are some artists who want to just go into a studio, work alone and show the work, and that’s perfectly fine. There’s a lot of artists that work that way. That’s just not what we’re doing at Sunset. So some artists can’t engage with the public, they want to have that kind of sacred space of their studio. And that’s just a different thing. It’s not bad, it’s just different.

So we look for things where people are already looking to work with the public. And then we’ll do an interview. Sometimes a project comes through when we already know, just kind of based on shared goals, we’ll have them in for an interview because we know that this project is going to fit with us. So usually we’ll have three to four artists come through the residency program per year. Separate from that, and this came to us, I think after our first year of having Sunset, was the membership program. We call it members because they pay monthly dues to have access to studio space. And whereas the residents kind of rotate through and they can stay for two to three months, the membership artist can be a member for six to twelve months and there’s a kind of limited renewable process if they want to keep on paying membership dues and having their studio—they can do it as long as they like. The application process for that isn’t as involved because we’re asking them to pay us money rather than paying them to come make their work. But they can have limited access to their studio all day, as long as they like. Still we do look for people who are going to be socially minded in their practice to an extent.

I think right now we have seven artists who are in the rented studio spaces. And then two of those artists, what we began this year in 2020, are a part of our fellowship program. And these are fully funded studios for six months for an artist of color or queer artists, either or. We created this as a way to, again, like Rachel mentioned, to increase access for groups who may not have had it in the past and, you know, do our part to make sure that we’re being equitable.

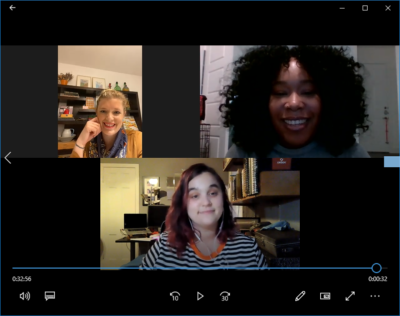

Kiara: Awesome. So with everything happening with COVID, what are some ideas that you have thought about as far as maintaining community engagement within your space?

Rachel: It’s tricky. Yeah. One of the things that was really challenging but I think ended up having a really beautiful output was for 2020, we will have had two artists in total. Like Emily said, normally we have more than that, but with everything happening, we had to slow things down and reevaluate. How can we create socially engaged art when we have to be distant from each other? So one of the ways that we’ve tried to approach this is working a little more intentionally with our resident artists. Our first artist here was Constance Y. White, and she was originally supposed to start in the spring, but we delayed it by a month to sort of take time to reevaluate and figure out how could we still make this idea of hers happen, but in this new format, and her project was already based on a much smaller idea of public.

She was going to hold a series of workshops for different women in the area across age groups. But the goal was that they were all going to be Black women and they were going to work with her originally through these workshops to talk about ways that they think about beauty and how they deal with and interpret their own relationship to beauty. But with everything happening, we were able to work with Constance and she was able to pivot that to being a digital format. So she worked much more individually one-on-one rather than with an entire group. And when she talks about it, she talks about how that it was definitely a different experience because the group brings so much energy and there’s like this shared understanding that people can come to these ideas together and support each other in a space. But when you work one-on-one, you also have the opportunity to go a lot deeper than you would in a group environment.

So she was able to still make her project happen, where she would interview these women one-on-one through things like Zoom, and then she would go and make collages inspired by them. And with their input that it was a lot more about their personal identity and thinking about their internal self, rather than thinking about how they understand their external facing self. Through that, she made a series of collages that were really impactful. I think she’s gone on already to think about new interpretations of them, and she’s taken them from a physical format that she created in the studio of actual glue and paper collages, to turning them into these really amazing digital animated or moving images that sort of realized that idea in a new way. Overall we’ve had to slow down quite a bit this year, but there have been really impactful works that have come out of everything that’s happened.

Kiara: That’s awesome. I definitely see a lot of people’s practices being moved more towards the digital, which is nice because you’re still able to have interactions like the one that we’re having right now and being able to still communicate. What are your goals, I guess, your long term goals for Sunset Art Studios? Where do you see yourselves in five or ten years? Or where would you like to see yourself?

Rachel: Emily? You want to go first?

Emily: Yes. I think having more financial stability. We recently became a nonprofit in 2018, and so that’s opened up a broader range of grant funding that we’ve been able to do and also fundraising, but I think we’ve got more work to do there in order to make sure that our finances are stable so that we can continue coming up with ideas and making them happen. With that said we’ve made a ton of progress in, I guess almost five, yeah is it five years now, Rachel, this fall?

Rachel: Yes. This month!

Emily: That’s our five-year anniversary!

Rachel: Last week!

Emily: So in the five we’ve quadrupled our operating budget and been able to sustain it. It’s kind of tapered off, it’s at a holding point for now. We’ve got some growth to do there just in terms of financial stability. And then with that, we would love to buy a building—our building or a different one still located in Oak Cliff so that we can have some secured longevity and then yeah, go work.

Rachel: I was just gonna say we’ve talked a lot about the building component because I think we’re both very aware that Oak Cliff is in the process of gentrification. And we’re both very aware that artists contribute to that process of displacement for people and being able to secure a space that will be ours, where we won’t be pushed out and rents hiked up. And then all these other things down the road that happened to where historical locations get bulldozed for luxury condos. Right. So part of the goal of buying a building is being able to do our part, to put a stop in that process and to see if we are able to put that stop in. And what kind of impact does that have on that whole gentrification process and how can we impact that and speak to it in a more long term way? What else were you going to talk about? Emily?

Emily: I think increasing the money that we pay to artists is another thing that I would like to continue doing. When we first began, our residency program was unpaid and artists just received free studio space, which is still, you know, a kind contribution. But then actually Kiara you are our first paid resident.

Kiara: OH what I didn’t know that!

Emily: No! We had two before, but it was at a smaller amount. And so you’re first kind of like the full amount that we had, and that year we paid all of our residents that amount, which feels more like a true stipend. I think at first it was like, here’s a little bit so you can cover material stipends. There are stipends that we paid to artists during the residency, and then also making all of our membership studios have lower costs. This is something we can do when, if we own our own space, you know, increasing fellowship studios we have that are fully funded and then keeping the ones that are membership paid at really low cost.

Kiara: Okay. Nice. Well thank you all for participating in this interview and sharing your stories and more information about your studio space. I really appreciate it. Do you have any closing remarks or comments about anything?

Emily: Something! I don’t have anything eloquent to say now at the end. It’s just been great to watch how Sunset has shaped Rachel and I as artists. I think there’s a clearer picture of the kind of work that feels meaningful to us. And actually I have another thing that’s coming, the juices are flowing. I think since that is one of those things that continues to energize me and I can have days where I’m totally drained from working outside of Sunset, and then I need to go to the studio to do X, Y, Z, and my energy gets back up. So I totally get my second wind and without fail every time. To me, that just means that I’m doing something meaningful.

Kiara: Yeah, yeah, for sure.

Rachel: I think the other side of that too, that’s been really meaningful for us is there’s that individual return, right? Taking the collaboration, going back to that individual space, but something else that’s been really significant for us is being able to see the artists that we work with. And while we’re sad anytime an artist has to leave, whether it’s because they can’t do the member studio anymore, or they don’t need the space in the same way, or it’s the end of a residency and it’s time for somebody to move on and someone else to come in—that part’s always sad—but it’s always been incredibly rewarding to see what is that person doing next. Not that there has to be a pressure or an expectation on that, but it’s just we’ve always enjoyed and felt really privileged to see every artist that came through, how did they transform the space, how they transform their practice, how they change us, and then what that looks like as it impacts the next part of their life that’s after us. Yeah. I’m just so proud of everybody that we’ve been able to work with and feel really honored to have, you know, shared the community so far with everybody that’s come through. It’s been really neat.

Kiara: Yeah. Just piggybacking off of what you are saying. I definitely benefited a lot from being in your program because I wasn’t aware of what I was doing with social practice until I was in your studio and we were working together and just, yeah. I feel like it really developed my practice so much and I thank you for that.

Emily: Oh, well, thank you for being a part of it. Congrats on all your new things that you’re doing. It’s really exciting.

Kiara Walls is a teaching visual artist, originally from LA but now stationed in Dallas, Texas. Her work is centered around increasing awareness of the need and demand for reparations to repair the injuries inflicted on the African American community. This interpretation is seen through many forms including drawings, sculptures and video installations.

https://kiarawalls.com/

Sunset Art Studios is an arts non-profit in Dallas, TX focused on social practice. Sunset Art Studios operates an artist-run studio space, residency and gallery where they focus on object-making and the artistic process as access points for empowerment. Their space moves towards establishing sustainable systems of celebratory inclusion and support.

Since co-directors Emily Riggert and Rachel Rushing opened in May of 2016, Sunset Art Studios has increased access to the arts in southern Dallas with area partners. This is done by providing free studio space to artists who identify as a part of marginalized groups and offering free community arts programming to reduce geographic and social barriers of seeing and engaging with art.

Sunset Art Studios continues to evolve and grow prioritizing the need to explore and resist systemic exclusion from the arts. Their strategy for fighting against traditional hegemony in the art world (re: white supremacy and the patriarchy) includes an inclusive artist sustainability program, residency program, and public programming. http://www.sunsetartstudios.com/

The Cascade of Possibilities

“I account for the context, and I ask myself, what is this going to do to the experience of the work? I don’t forget that many different people might visit the space, from the most sophisticated intellectual to someone who is encountering art for the first time.”

In 2013, I first became acquainted with Enrique Martínez Celaya and his work when I was an intern at contemporary art museum SITE Santa Fe. Martínez Celaya created an exhibition called The Pearl. I was struck by its myth-making and how it built an immersive environment as a point of entry for audiences. The installation created a world around Martínez Celaya’s childhood experiences and felt like a guided meditation full of different paintings, sculptures, and sounds. Each weekend, I would spend four to five hours giving tours of the exhibition and noticed a visceral audience response, mainly regarding The Cascade, a sculpture of a boy crying into a bed of pine needles that ran the entire length of the exhibition space. The tension of holding back emotion was broken in this room, and I found that on more than one occasion, people began to cry. At the time, I was interested in the in-between space of public and private displays of grieving. Reflecting back years later, his exhibition was the catalyst for my thinking about audiences and the intimacy of dialogue. I started to ponder if art could create opportunities of authentic emotional expression within a present and engaged audience.

Additionally, I was interested in Martínez Celaya because of his story and how he decided to commit himself to his art practice. Born in Cuba and raised in Spain and Puerto Rico, he started painting seriously as a child, but embarked on a career as a physicist, researching superconductivity at Brookhaven National Laboratory and patenting designs for several lasers. Then he pivoted sharply back to creating art. He works in many mediums, creating site-specific paintings and installations for places as diverse as the Berlin Philharmonic (2004), the Cathedral Church of St. John The Divine (2010), The State Hermitage Museum (2012), and SITE Santa Fe (2013).

Over the years, I have been contemplating his process of pondering questions, regardless of the pathways which he found to pursue answers. For example, though Martínez Celaya had an extensive career as a former physicist, within a singular moment at a lighthouse decided to commit himself fully to his art practice—noticing and honoring the nuances within himself that began early as a child, nuances that could only be explored through art. Martínez Celaya challenges the idea of what an artist does by embodying what people often think of as opposite sides of a spectrum: art and science, left and right brain. I have myself spent a portion of my career in the finance industry using my mathematics skills to prevent money laundering and elderly abuse, and though I did not have a dramatic moment of clarity, I found that my practice at the bank became social practice in nature. I realized that the nuances of my questions were always present and I knew the answers could only be explored through art. My clients became collaborators to the environment of my office within the time we spent together, much like how I felt I was a participant in the world of The Pearl as an audience member. Years after experiencing his exhibition at SITE Santa Fe, I thought about what it means to be multifaceted within my own art practice by combining my knowledge on socioeconomics and art. Now that I am in graduate school at Portland State University’s Art and Social Practice Program, I have the chance to talk with Enrique Martínez Celaya about subjects like audience, gatekeeping, context of environment, and the future of status-quo systems of the art world all these years later.

Shelbie Loomis: In 2013, I was struck by how completely you were able to encompass the exhibition space in a way that allowed for the audience to wander through using multiple forms of artwork, like your sculptures, paintings, writings, music, to form a created environment. I had really felt invited into this space as a collaborator and participant in the experience alongside your artwork. What role do you think the audience plays when experiencing your art?

Enrique Martínez Celaya: People (artists) talk about the importance of the audience, but I find that one can make a lot of assumptions about audiences that are often incorrect. For instance, the assumptions revealed by a phrase like, “Our work forces the audience to question,” don’t usually apply to sophisticated audiences who are likely to have already considered whatever is being thrown at them.

I primarily try to make work as an inquiry guided by the values and judgements that reflect my need for clarity as well as by a constellation of thinkers, writers, artists, and scientists who have been influential to me and whose work I respect. They are my first audience, which is, of course, an imaginary audience. In the case of SITE Santa Fe, it was a bit more specific than that because the exhibition space had a movement, and I wanted to imagine how people would move through the space. I was actively thinking of the audience as somebody who is present in this space moving through it, so I considered how that person would be invited or nudged in one direction or another by their words. When I create environments, I think of that movement through space—that unfolding of the audience—in a similar way one encounters a poem that unfolds in time. Beyond that, I am careful with the assumptions I make about the audience for my work, and I am especially wary of the facile wisdom and challenges artists sometimes like to impart on the world.

Shelbie: It’s interesting to me because you are in a way assuming a guide position, by allowing the artwork to guide the viewer. But has there ever been a situation where the uncontrollable variable (which is the audience) shifted or unintentionally shifted the environment, so that it might be interpreted differently? Have you ever experienced the audience shift the presence or the essence of an exhibition?

Enrique: Oh, yes, of course. I can think of a man—who I have since gotten to know—who cried for a long time in the space with the crying boy (The Cascade). That man’s tears changed that space by his engagement. So, the work is placed in a space as a catalyst for possibilities, and those possibilities come in many different forms. The audience is transformed by the environment, and in turn, it is transformed by their response. I did a project for the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine. People go there for worship, and in an environment like that, the work is directly or indirectly part of their worship, which is very different from a museum when visitors see the work as part of a cultural conversation. So, that shift, for example, makes the work and the audience have a different relationship to one another than what is usually assumed.

Shelbie: Is it intentional for you? Or is that a wonderful surprise, like a byproduct of just creating and putting a lot of effort from yourself outward?

Enrique: No, it is intentional. I chose to do the project at St. John the Divine because I felt it was an environment that demanded more from my work and me. There’s a kind of clever or self-important conversation that is common in museums or galleries that doesn’t make sense in the context of a place where somebody prays for their dead son. For someone like me, who is interested in certain kinds of questions, I want to take those questions to a place where they matter. Context and audience are related but they are not the same things. I account for the context, and I ask myself, what is this going to do to the experience of the work? But I don’t forget that many different people might visit the space, from the most sophisticated intellectual to someone who is encountering art for the first time.

Shelbie: It seems like you’re alluding to the fact that there is a certain amount of gatekeeping. And in that anticipation, you’re essentially eliminating gatekeeping and allowing it to be accessible through multiple gazes, regardless of who audiences are, to allow people to project their own humanity in the work and allow them to come away with their own assumptions.

Enrique: Gatekeeping is one way of thinking of it. There seems to be a tendency for people in cultural arenas to appoint themselves to the role of deciding whether you’re good or not good enough to respond to the work appropriately. Ultimately, I make my work to try to understand something about the nature of things. So, when the work goes into the world, it interacts with the world in a way that might be unexpected to me. A work of art that is dimensional enough—has enough going for it, enough points of entry and enough references—can be approached in many different ways, so to prescribe what that experience would be like, and try to determine or control it, will not only do disservice to the work, but it also underestimates the possibilities of the artistic experience. The Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, the Berlin Philharmonic, SITE Santa Fe, and The Hermitage, are all very different contexts, so over-determining what will happen in one of them because I know what might happen elsewhere is a mistake. It is better to let the work do its thing.

Shelbie: This kind of ties into a question that I’ve been thinking a lot about in terms of your work. If you hadn’t been a physicist and gone through a certain amount of formalized training, would you still be doing the work that you are doing today?

Enrique: I truthfully don’t know the answer. On the one hand, everything I have been and every training I have undergone affected me. On the other hand, when I look at the work I was making in my early teens, and notice the preoccupations I had, the kinds of things I wanted to make, the part of the world I wanted to understand better, they seem similar to what concerns me today. For example, a lot of the literature I was interested in when I was thirteen and fourteen is the same literature I’m interested in at this moment. My understanding is perhaps more sophisticated now, but the things that moved me then, still move me today.

Shelbie: Do you feel there is a strength for artists who are pursuing multiple complexities of fields of knowledge and combining it under the gaze of artwork?

Enrique: It’s not an easy question to answer because I think there are different embodiments of that question. I think the possibility of combining different fields of knowledge and sensibilities can be very powerful. And I think ultimately, the divisions between these fields are often arbitrary in the sense that what we’re after is understanding things better and expanding the island of what we know. So, physics, poetry, or art, are different versions (more or less) of the same thing. On the one hand, there is power in combining all these disciplines and moving seamlessly between them. On the other hand, there is a tendency when people work with multiple disciplines to become dilettantes. Instead of offering new ways to get deeper, the approach becomes an addition of superficially-understood concepts brought together. The result is five concepts that are superficially understood and superficially developed, but because not everyone knows all five concepts you brought together, you appear to yourself—and perhaps also to the world—as some sort of messiah of knowledge. I am all for movement across fields, but I’m also interested in depth within them, in really trying to understand the consequences of a particular line of inquiry or thought by understanding it. If you’re going to use philosophy, then try to understand philosophy. You don’t have to use it, but if you’re going to use it, use it well.

Shelbie: 2020 has brought a lot of interesting obstacles for artists. What do you think the future of art, the artist, and the artist’s role is moving forward after this year?

Enrique: First, I will tell you what I would like it to be, then what it is likely to be. The reflections and clarity artists can provide are more needed now than ever. The connectivity of social media and the triumph of greed and capitalism have made us more lonely than ever, and many feel alienated and disenfranchised. Artists can bring forth self-awareness and connection to a value system that is not dependent on how sellable or popular something is. However, what’s likely to happen is that artists will become voices for trendy ideas and subjects. I think galleries and museums will be damaged—at least temporarily—by this pandemic, and there will be fewer opportunities for artists. Also, the situation is going to get harder for artists in terms of livelihood.

Shelbie: There’s an interesting component, which is the ability to exhibit or engage with a community. Do you think that there are other means of outreach and bringing art into communities apart from the gallery?

Enrique: I think you can be engaged with the community as a part of your practice. You can do projects in the world or you can create your own opportunities. I think artists are shockingly conventional in that they often wait for permission before doing something. You can show your work on the sidewalk if you want to. You can go to a public school and work with kids. Artists wait for the system to allow them access to the alternative space, to the gallery, to the museum or the biennial. This can be very limiting, and I think if anything has been revealed during this pandemic, it is what happens when those things are not there.

It will be a rough time, but I think there is hope. Unlike a movie director, who usually depends on a big network of people, as an artist you can make a show in your living room, or you can collaborate with people. The possibilities are open to your imagination, and we don’t always take that seriously enough.

Enrique Martínez Celaya (b. 1964) is an artist, author, and former scientist whose work has been exhibited and collected by major institutions around the world including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and many more. He is the author of books and papers in art, poetry, philosophy, and physics. Received a Bachelor of Science in Applied Physics and a minor in Electrical Engineering from Cornell University, and a Master of Science with a specialization in Quantum Electronics from the University of California, Berkeley. Part of his graduate research was conducted at Brookhaven National Laboratory, and while there he painted the Long Island landscape. Martínez Celaya was born in Cuba and raised in Spain and Puerto Rico.

Shelbie Loomis (b. 1992) is a multidisciplinary artist and self proclaimed economist who explores issues of class, labor/housing/food rights and critiquing economic systems of indentured servitude like debt. She explores these issues through the use of story-telling, archiving, drawing, and social organizing. Her socially engaged projects are a commentary on the subversion of labor norms, nomadic lifestyles through RV-ing, temporary housing, and self-sustainability through the growth of food. She is based in Portland, Oregon, and is originally from Santa Fe, New Mexico.