A History of the Early Days of W.A.G.E.

March 26, 2020

Text by A.K. Burns and Spencer Byrne-Seres

A.K. Burns talks to Spencer Byrne-Seres about the beginnings of W.A.G.E, an artist initiated non-profit that advocates for sustainable relationships between artists and institutions.

Spencer:

In thinking about the foundation of WAGE, I’m interested in artist compensation, and how WAGE was recognizing those things for the first time. I’m really interested in what led to the coming together of this group to talk about these issues. What were those conversations initially about?

A.K.:

Well, in its inception, it was really A.L Steiner and I just having some gripey conversation and complaining. It stemmed from something that Steiner brought up because she had just been in Spain and had done this installation where she actually got paid a seperate fee on top of the exhibition costs being covered. Which was something she hadn’t experienced before. We talked about how rare that was. And began to really pick apart and question why it was so rare.

This conversation occurred in 2007, probably about a year before we made our first public statements as W.A.G.E. I had also just started grad school, so I personally wasn’t interfacing with arts organizations on that scale yet, but I had experienced the problem of how to cover the cost of producing a work for exhibition and the ongoing costs of supporting my practice, which always required (and still does to this day) having a job on top of my work as an artist. And of course I was very much in the midst of incurring the debt of grad school, as an ‘investment’ towards that career. And while I knew a few artists who survived off the art market (people with extremely focused object/material based practices), most, even those with very large international careers were teachers or had some other means to support their work.

Once we started to recognize that it was possible to be paid for the work we do as artists then we began to wonder why there seemed to be systemic obstacles to being paid for what we contribute to society? And by work, I do not mean the artwork itself, I mean all the office work it takes to run a studio and produce exhibitions beyond just the making of the work. So many emails, archiving, PR, promotion, writing, mapping out, planning, organizing, communicating and the management of others for various aspects of production. I would say personally, about a half or a third of my time in the studio is actually spent making artwork.

Also in 2007, we were on the threshold of the economic collapse of 2008. But we didn’t know it yet. When we looked around the art market appeared to be rapidly proliferating. Everyone was rushing to get MFAs like never before, until the mid-90s it was fairly rare for artists to get MFAs. Art Basel founded Art Basel Miami in 2002 and from there art fairs began popping up. It’s now a nearly continuous stream of fairs year round. Yet when we looked at ourselves and our peers, primarily queers, women, and those working in less commodifiable modes of art—which makes up a substantial part of art production and is highly valued by museums and non-profit institutions because it is seen as more ‘radical’—it became clear that this boom served to support very few. And that everyone else was working double time to have a very basic level of economic sustainability. I think there was, historically, a notion that artists were poor until they died (and value increased post mortem). But by the 70s and 80s we began to see artists make real money within their lifetime. The romanic model shifted as neo-libral policies and late capitalism took hold in the Regan/Bush/Clinton eras. By the late 90s into the mid-2000s I think it became a kind of fever to create a massive art market and in a belief that artists would be supported by that market. Silently we were all speculating, assuming it was just a matter of time till we ‘made’ it.

Spencer:

Right.

A.K.:

Then it was like a light bulb went off, ‘making’ it, ie. meeting the demands of having an art career, has very little to do with the ‘market.’ And we called up a group of friends, of other artists, inviting them over to engage this discussion more broadly, I don’t remember who all was there. K8 Hardy for sure. I know we called Sharon Hayse but she couldn’t make it. And from that meeting in early 2008, we did what you do when your angry about an issue, we wrote a manifesto. The W.A.G.E. wo/manifesto.

Sometimes I think some of the success of this project was that we did not take ourselves all that seriously. Because it all seemed so far fetched. We wrote a manifesto so that we could vent. So we could get it off our chests, but I don’t think we understood it as structural to making something far bigger.

Spencer:

How did W.A.G.E. go from being a mode of venting to a real public project?

We also didn’t really have an idea of what it meant to publish the wo/manifesto or how to put it into the world. But then K8 Hardy got invited to the first Creative Time Summit: Democracy Now to give some kind of stump speech. K8 was like “Well, I don’t have anything in particular I want to present, but I have this group that I’m working with. That we’ve got this idea. We’ll make speeches.” The three of us (Hardy, Steiner and I) wrote speeches.

So on September 27, 2008 we went out there gave those speeches and beforehand we were joking around, saying “Okay, this is probably the end of our art careers. But I guess we didn’t have much to begin with so it doesn’t really matter.”

It just seemed like a great opportunity to make some noise about something that we’ve been thinking about. And then from that moment on, it was like a deluge. We pointed out the elephant in the room and everybody was like, “oh this is really important and we have to talk about this and think about this and act on this.” It was also, of course, on the threshold of Obama’s election. At this point, the election had not happened, but the economic crash had. And it would seem like economic collapse would be a bad time to ask for change and more fiscal support. But it was good timing in terms of people being willing to rethink old models.

From that moment on, there was allot of requests to do talks, and educate people on the ideas about inequity, especially in the non-profit model. Which is what W.A.G.E. focuses on.

Spencer:

Can you explain how you built W.A.G.E.s critique around issues in non-profits as opposed to the for profit gallery system?

A.K.:

Well galleries, as fucked-up as they are have an economic system in place. And I think we were aware early on about having a single issue to build our platform on. With the small amount of resources we have as a group, remaining single issue, I think, is why we are still functioning. And because the non-profits (arts spaces & museums) made up most of our careers and of those around us. You can have a fairly huge career but spend most of your time rotating through public institutions, for some artists galleries are more of a badge of alignment than an actual source of money. And galleries like to have ‘radical’ artists who don’t really sell on their roster to make them look more diverse.

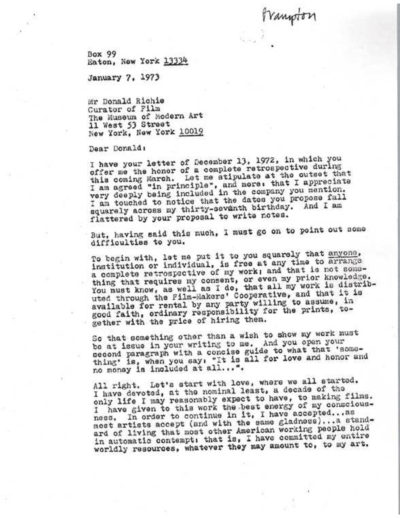

When we started to break things down, it became very clear. We were like, “Okay, these are nonprofits. They are tax-free because they are educational institutions.” Then you have to wonder… “Who’s the educator? Oh yes, the artist is the educator.” Then the educator must be paid for their work just like everyone else at the organization. And we also started digging into the archives at MoMA where we found really amazing documents like the papers from Art Workers Coalition and the Hollis Frampton letter to the Director of MOMA, when they wanted to do a retrospective on his films. And he was asking for something like $200 for the whole retrospective. Some measly amount. Over the course of a four page letter he painstakingly explains how the projectionist expects to get paid, and the how the person who develops his film expects to paid, etc, everyone else in the process of making and displaying art expects to get paid. And Frampton had gotten this letter from the director saying, “It’s was for love and honor so there’s no money included.” And Frampton is like, “I can’t tell all these other people that it’s for love and honor.” It’s a very eloquent rant on how there’s an illogical romance around the artists. That somehow we function outside of the economy because we have this passion that drives us. Like we’ll make the work regardless. But no matter how illogical it is to be an artist, it’s no excuse to be seen as free cultural labor. Or to expect that the cultural capital you get from showing at the MoMA will result in sales. That’s not a real equation.

Spencer:

There is this idea that somehow the freedom involved to do what you want to do means you don’t have to suffer through a regular type of compensation structure or something.

A.K.:

Right. Also how do you compensate for something like this? And this became a real problem for us when we started to think about how you create any kind of equity. How do you put a number on art production or the other kinds of labor involved in exhibition? People do it all the time for the gallery system. But that’s also just a weird fiction. It’s like well this painting’s bigger than that painting so it cost more. That has nothing to do how much work you do to make it. There’s no labor ratio.

Spencer:

How hard you try on the painting. How many hours you have spent on it…

A.K.:

Like I think for us we were like, “Well, if we’re really going to put energy into making this is a real organization, we want it to be productive and make real change in the world.” And Art Workers Coalition is amazing. They made a lot of documents and they supported allot of causes and protested and were crucial to the dialogue going on at that moment around the vietnam war, etc. But you look at their list of demands and most of those things still have not been met from their 13 demands. I think one of the main things they got was the free nights at museums which are now “Targets-free” nights. And they’re one evening a week. But the AWC, they really wanted free museums. Access to culture for everyone.

Spencer:

I wonder if the status quo version or the reason for the lack of compensation was because you have this gallery model. It was assumed that you were selling a bunch of paintings all the time and that was your source of income. And then these exhibitions were, like you said, for love and honor or whatever. What has shifted in terms of artists’ practices and what they’re doing, that this came into contrast?

Is artists’ work not commoditifiable in the same way, when you engage with an institution? Or is it a status quo version, the assumption that somebody comes from the museum and just picks up the painting from my studio. I don’t have to do much work. It’s already there or something like that?

A.K.:

But it’s never… Even if you’re a painter, it’s not that simple.

There’s a lot of coordinating and talking with the curator and other aspects of an institution. It’s like it’s a farce that there’s not a whole other layer of labor going on beyond the making of work. I’ve never had a show where a curator just takes something and runs away with it and never talks to you about it. No artist would want to engage in that. It’s an ongoing conversation and it’s many meetings and it’s planning and it’s like, and depending on the scale of the show there could be a public conversations or writing to coordinate. Then there is coordinating pick-ups and drop-offs and packaging the art, finding where it is stored. Usually galleries or studio assistance handle allot of those parts but the people who have those resources are the people who have money to pay for that. And then install can take anything from weeks to a day depending on the scale of the show. I think it’s also shifted a lot in the sense that I think the MFA industrial complex really upped the stakes of what artists are investing financially. So allot of artist start from a point of debt.

Spencer:

It’s so interesting to think about the MFA and its role in shifting the economy of being an artist. All of a sudden people were willing to go $100,000 into debt just to be an artist, right? And that then shifts the stakes of everything, right?

A.K.:

Artists don’t really need MFAs. Except to teach but they used to not even need MFAs to teach. I don’t think MFAs are a load of shit. I think they can be a very productive time for artists, i mean I got one and I teach in MFA programs, so dare I be a hypocrite. But I know I felt like I was buying time I couldn’t get on my own because I was so busy working instead of making art. So it’s a perverse situation where you buy yourself time to develop because there is no time in this economy that doesn’t cost money. Especially given the cost of living in cultural hubs like New York.

Spencer:

And one of the few jobs that exists for an artist to teach, right? Like that’s a salaried job where I get to be an artist and paid for my knowledge in that field.

A.K.:

It’s a real Catch 22 in many ways. MFAs to teach but not enough well paid positions for the amount of MFAs so that’s not really a sustainable model either. Hence why nonprofits need to step up to the plate and pay fees for exhibiting. We need these things to have a healthy cultural eco-system. Artist fees aren’t about getting rich, they are about providing more support for diverse practices.

Spencer:

And it’s all within a capitalist structure that we live in now. It’s economized no matter what you are doing.

A.K.:

Yes first it was the loft living boom of the late 90s that transformed every medium to large city in the United States (San Francisco, Portland, New York, LA..etc) and dare I say worldwide became deeply gentrified and turned into these hipster villages. A lifestyle that has become a commodified, rather than a form of survival for those who need other kinds of spaces for the specific way artist work. And now many artists go without studios or have downsized practices out of their bedrooms.

Then came the gig economy and things like WeWork that also evolved from practical situations that were created to manage the precarity of being an artist. I often think we have a much bigger influence on society in the way it’s economically structured than through the culture we make. Do you know what I mean?

Like this whole gig economy stuff and the way that artists function, is a very high risk lifestyle. It’s actually not something that large portions of the population should be doing. Nor is a loft a great way to live, unless you have money to burn on a massive heating bill.

Spencer:

Right. There’s no job security. There’s no benefits.

A.K.:

Yeah, it’s just like you are spinning your wheels in something that is exploiting you. And I think part of what W.A.G.E. is acknowledging, is that, we as artists we are participating in being exploited. Because we are often willing to ignore the monetary relationships to how we move through the world because we are ‘dreamer’ types. I mean you have to be, like I said, kind of nuts to be an artist. We’re not the best at making logical decisions for ourselves, I think. W.A.G.E. offered a kind of retraining not just for institutions and there responsibility to artists, but the way artists are responsible for the systems they participate in.

Spencer:

And there’s this perception that it is a privilege to be an artist, right?

A.K.:

Well, it enforces that. If you’re not paying the educator at a nonprofit organization and your a tax deductible organization, you’re actively eliminating the artists with fewer resources who cannot afford to participate for free. It very much benefits the artists who are already privileged enough to take the risks.

Spencer:

Yeah, and I think about that a lot. And risk, in general, a lot about who’s able to take risk, right?

A.K.:

Yeah, and then there’s the burn out, where all of us are taking risk, risk, risk and at a certain point, you’re like I can’t do it anymore. Can I sustain this? What’s the value of my limited amount of life energy and labor? You know what I mean? Yet the art system seems to want it, right? They’re hungry. They’re just pushing out exhibition after exhibition after exhibition and they need programming, programming, programming.

It’s been almost 12 years now since we started WAGE. And there’s a whole younger generation of artists and they’re not fucking around. They don’t go and do something if someone’s not paying them. Like they expect to have a discussion about money. I see this more and more over the years since we started. It used to be an almost unheard of conversation.

Spencer:

And a big part of it, I think, is recognizing that social capital doesn’t feed you. Like feed your body.

A.K.:

Yeah, that romance is dead. W.A.G.E. killed that romance. That was our primary goal. I think that’s the one good thing that we did. Your celebrity status is not going to feed you.