Category: Issue 3: Recreation

Tia Kramer: Scores for Creative Exercise

Text by Tia Kramer

I Remember Well: Recreation and Spiritual Striving

Text by Nola Hanson

By Nola Hanson

MRI WRIST WITHOUT IV CONTRAST LEFT ‐ Final result ﴾03/21/2019 11:36 AM EDT﴿

3.26.2019

I’m in Waukesha, Wisconsin for my grandmother’s funeral. I’m playing basketball at the YMCA.

Older people walk in circles on the track above the court. A man stops, leans over the railing with his forearms and looks down at me.

I’m trying to hit a spot that hasn’t changed since the first time I aimed for it in the same gym,

at age five, when I looked like this:

—

My mom signed me up for basketball camp; she bought me a heather gray tank top to practice in; I remember the adhesive strip that ran down the right side of it.

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

I didn’t want to take it off, I thought it was part of the uniform.

—

MRI WRIST WITHOUT IV CONTRAST RIGHT ‐ Final result ﴾04/20/2018 1:08 PM EDT﴿

—

I remember the wood, nylon nets, the orange rims. The mesh jerseys we used for scrimmages. The silver whistle that hung from from a black braided rope on my coaches neck.

During games I’d stick my tongue out and lick; from the heel of my palm to the tip of my middle finger. I’d lift my feet up under me, and slide my hands over the rubber soles of my sneakers to remove the dust, so I could hear them squeak. I had to stop after a teammate saw me, and said that’s the same thing as licking the floor and I couldn’t tell her: I know.

—

At Sunday school when I asked what heaven is they said picture your favorite place;

it’s like going there and never having to leave. I imagined the court I’d seen at the Milwaukee Bucks game, but all of the people were gone except me.

—

I remember being six, sitting on a 5th graders lap in the auditorium. Everyone sat in the dark and faced the same direction, reading lyrics to Christmas songs that were printed on transparencies and projected onto a screen. When he found out I wasn’t male assigned at birth he screamed, pushed me off, and said he was scared of me.

“My body was given back to me, sprawled out, distorted, recolored, clad in mourning…” (Fanon, 259)

I felt like I lost a game I didn’t agree to play in the first place.

—

Recently, back home, my mom and I stood in my sisters kitchen. She asked did I remember what I said to her at the mall the day before my grandfather’s funeral?

No, I forgot.

She said, “You looked at me with tears in your eyes and said ‘What the fuck am I supposed to wear?’”

Which meant, of course “Who am I supposed to be?”

“It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” (Du Bois, 2)

—

My grandfather, Leif, was the star quarterback on his football team in college, and after that, a World War 2 bomber pilot.

He was the person who taught me how to dribble. I remember his sun spotted hands floating over my head in the driveway.

We would go to Swing Time Driving Range and hit balls together. One of the last times we went, he fell and hit his back, smack dab in the middle of a wooden divider that separated the squares of fake grass.

He died when I was sixteen, in his living room with his mouth open next to an American flag folded up in a glass case, and a model of a Boeing B-17 airplane.

MRI WRIST WITHOUT IV CONTRAST RIGHT ‐ Final result ﴾02/04/2017 12:45 PM EST﴿

3.28.19

My cousin Nels eats Mexican food out of a plastic rust colored container. His spoon has a molded rubber grip at the end of it, and he drinks his Coke out of a big cup with a straw and a lid that twists off.

He says he pictures me skipping rope. The rhythm of it, the sound like a rubber band under my feet. He says he remembers the feeling and when he thinks of me he feels it in his body.

He says the last time my grandmother came to see him, she didn’t even make it around the corner to look at him. She leaned over the back of his hospital bed and kissed him on the top of the head.

“The more one forgets himself… the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself. What is called self-actualization is not an attainable aim at all, for the simple reason that the more one would strive for it, the more he would miss it.” (Frankl, 133)

4.17. 2019

I’m sitting at a table with Takahiro Yamamoto, and 10 undergraduate students.

He says, “Forgetting is important.”

MRI WRIST WITHOUT IV CONTRAST RIGHT ‐ Final result ﴾04/20/2018 1:08 PM EST﴿

7.12.16

While hitting the heavy bag at the New Bed Stuy Boxing Gym– home of former world champions Riddick Bowe and Mark Breland– I tear a ligament called the Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex. They call it the meniscus of the wrist. I get a cortisone injection and train on it for two years.

MRI WRIST WITHOUT IV CONTRAST RIGHT ‐ Final result ﴾02/04/2017 12:45 PM EST﴿

—

My friend and I are walking in Chinatown. We go into a Vietnamese restaurant. She swore there used to be fish tanks here, or is she going crazy? The waiter says yes, there were. They renovated a year ago and made room for more tables. When we order, the waiter calls her sir.

She says that when she started taking T blockers and estrogen, she had this feeling, like: oh, so this is what it’s like to be a person.

—

XR WRIST 3+ VW LEFT ﴾XR WRIST PA LATERAL AND OBLIQUE LEFT﴿ ‐ Final result ﴾02/07/2019 4:16 PM EST﴿

4.16.2019

My new roommate tells me she saw her ex for the first time in 15 years: “She was such a cute dyke,” she says, “…now he’s just an old man.”

- Works cited:

- Frankl, Viktor E. Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984. Print.

- Du, Bois W. E. B, and Brent H. Edwards. The Souls of Black Folk. Oxford [England: Oxford University Press, 2007. Print.

- Merton, Thomas. Zen and the Birds of Appetite. [New Directions], 1968. Print.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. New York : Grove Weidenfeld, 1991. Print.

Where I Play

Text by Roz Crews

By Roz Crews

I’m a “lonely only” and when I was a kid, I spent a lot of time by myself or with the neighbors. I knew that playtime meant I could choose to be alone floating through my thoughts or I could be with other kids, developing communication and negotiation skills. Both options were fun, but they required different kinds of mental energy. Playing together was difficult, and it felt like learning, which felt like work. Slow and painful, but then I grew three inches in one year.

I found freedom in privacy, and I frequently experienced self-doubt when I played in public space. All of the kids my age who lived in the neighborhood identified as boys, and they loved baseball, building stuff using power tools, video games, and skateboarding. Sometimes I ran alongside their skateboards pretending I was on a skateboard, but I preferred imagining doll weddings, catering fake events with real food, choreographing music videos for popular songs, searching for fossils in the creek, and narrating the lives of stuffed animals.

One of our greatest collaborations was called “House in the Trees,” and the project combined and benefited from our diverse interests: we built a series of structures between two small magnolia trees on the edge of our property, ate meals there, hosted group discussions, and used it as a backdrop for our life together. We barely left the neighborhood during playtime, and if we did go on an excursion, we usually went to a local park.

In the 1990s, Westside Park, the largest city-owned park in Gainesville, Florida had a few metal climbing structures including classics like a slide and a swing set, but it also had a really simple play object shaped like a spider. It was hard to climb up the metal spider legs, but if you could, you sat upon the spider’s back. Thinking about it now, I’m reminded of Louise Bourgeois’ spider sculptures:

“The spider—why the spider? Because my best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and as useful as a spider.”

—Louise Bourgeois

I felt insecure near the spider. I sat heavy at the juncture where its leg met the ground, and I felt incapable in contrast to my peers who could effortlessly slither up the slender metal limbs. This object stood in the park like a sculpture in a public garden, and I wanted to spend time with it by myself—to appreciate its beauty and persistently practice climbing its legs protected from the gaze of other people. I wish Louise Bourgeois was my grandma, and she could lift me atop the spider where she’d whisper into my ear: “You are patient and reasonable, dainty and subtle, completely indispensable.”

In 2009, the park was renamed Albert “Ray” Massey Westside Park and Recreation Center in recognition of a man who is known regionally as the “Grandfather of Recreation.” In a news article about the renaming, Massey is said to have made recreation possible in the city of Gainesville. This makes me wonder: What does it mean to recreate?

I hate the idea that a park or a playground or a structure or a person would be designed and designated as the facilitator of play.

If it were up to the spider, I’d be alone and crying, destined to a life in the mulch. Eventually, I would create a habitat beneath where I could tunnel into a crystal cavern in the Florida aquifer, but that would take years. At some point during my childhood, the spider was removed, and all the simple metal sculptures were replaced with plastic slides and coated metal walkways with pictures of frogs and pirate swords emblazoned on the ship facades. This type of aesthetics for a playground are pervasive. They function like dictators of play. When I was younger, I yearned for these brightly colored plastic playscapes because they were clean and bright and told me what to do.

In contrast to the plastic play utopias that started to appear all around me in the 1990s, there was an incredible, free-standing wooden world called Kidspace designed by famous playground architect Robert Leathers. On special occasions, I would drive fifteen minutes with the neighbors to visit the playground, stopping to get Subway sandwiches along the way. My neighbor’s mom seemed to like taking us there—maybe it was an escape from reality for her, too.

In 1987, parent volunteers from a local elementary school raised $48,000 to build Kidspace. After purchasing supplies and architectural plans, members of the community came together to build the playground in only four days. It covered 15,000 square feet of a formerly empty field behind the school, and it included “a haunted house, boardwalks leading to suspended networks of automobile tires, to rope catwalks, to parallel bars, to slides. There [was] an amphitheater with a stage, a wooden car, a rocket ship, even—something special for Gainesville kids—a big wooden alligator.” After school hours, the park was open to the public.

All of Leathers’ playgrounds are built by “community volunteers,” usually the parents of the kids who use them, and in this case, a representative from Leathers’ architectural firm in Ithaca, NY came to the site to collect ideas from students about what they wanted to see in their playground. The kids suggested: “pretend go-car shark car,” “a robot that talks,” and “a fish sumdareem (submarine) that goes underwater that kids can get in and see fish and sea animals with 5 windows.” None of those things made it into the finished park, but maybe the kids felt a sense of ownership anyway as a result of this process. After twenty years, the playground was dismantled when it was determined that the elaborate wooden structure was leaching arsenic into the soil.

Apparently, Robert Leathers used to wear a red T-shirt with the message, WE BUILT IT TOGETHER. When I think about the process the parents must have gone through to make this playground a reality, I’m impressed by the collaborative spirit and I see their smiling faces as they hammered the wood together, but I also think about the privilege they had to volunteer their time fundraising and building. I’m not aware of a project like this existing on the east side of Gainesville where the families at the time were mostly working class. When I traveled to Kidspace, I could tell this structure wasn’t just a sculpture, it was infused with community care and consideration, and it was a platform where we as kids could design our own ideas and experiences—an opportunity the ordinary, city-funded playgrounds didn’t afford.

When I was sixteen, a veil was lifted and I realized the amount of production adults require in fostering and maintaining play in plastic playground environments. I was hired as a “play leader” at O2B Kids, an Edutainment Company that offers programs for children 0 to 13 years old. As a play leader, I wore what all the play leaders wore: khaki pants and a branded purple t-shirt. I had a pixie haircut, and once a kid asked me, “If you’re a girl, why do you have short hair?” I said it was because I am a princess, and every real princess has short hair. News got around, and I reveled in my new “Neighborhood Time” identity. There were ways to subvert how Neighborhood Time was used, but ultimately, it was a commodified experience contrived by the company, as stated on the O2B Kids website:

Neighborhood Time is a time to give kids a choice of things to do – just as they would experience in a safe neighborhood of yester-year. Choices include a combination of program calendar classes, non-scripted inside and outside play, and counselor led activities. This provides crucial time for your child to explore, make choices, develop friendships and gain independence. Our Counselors are stationed in zones to facilitate safe play.

The entire playscape exists inside a building adjacent to a mall, and I really question the amount of agency children have to make choices in that space.

Everyday at the end of my shift, I crawled through the plastic play tubes, tediously cleaning the shiny interiors. While I wiped away germs, the tubes vibrated with the sounds of dance class (Lil Mama’s Lip Gloss was popping). Not only was I hired to facilitate “Safe Play,” but I was also required to make sure the environment remained sterile for all the kids who came through. I like to think of this place as a painting. All the colors swirl together to make the secure world we want to be in; where the neighborhood is inside and the birthday party is purchased as an all-inclusive deal. But, instead of a birthday party, it’s actually a cruise where you know everyone, even the strangers. The ocean clouds start melting onto everyone’s faces, and there’s nothing you can do about it.

I recently came across a photo of the Noguchi Playscape designed by Isamu Noguchi for Piedmont Park in Atlanta, Georgia. I thought it was a sculpture park, but then I read more about it: it is a playground that was funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts as part of a project with the High Museum, completed in 1976. The Playscape reconceptualizes play equipment as sculpture, obscuring the divisions between fine art, real life, and playtime. Supposedly, Noguchi’s goal in designing playgrounds was to make sculptures a useful part of everyday life. At first, the sculptural quality of the playground made me feel excited because it looked like an enjoyable way to experience art, but later, I started to worry about the dangerous quality of how it might administer play. Noguchi calmed my worry with his vision:

“The playground, instead of telling the child what to do (swing here, climb there), becomes a place for endless exploration, of endless opportunity for changing play.”

—Isamu Noguchi

When I saw the photo of the playground in Atlanta, I was transported back to a moment in 2012 when I visited the Isamu Noguchi Museum in Long Island, NY. During that visit, my friends and I intuitively began shaping our bodies to match the forms of the sculptures. We were freely playing in a very reserved, private yet public space. The photos of the playground got me thinking about my own necessary conditions for play, and I reflected on the publicness of the playground and the privateness of the museum. I searched for images of that trip to New York.

Now I work at an elementary school, and I wonder if the students feel permission to play there. My job at the school is to help organize programming for the King School Museum of Contemporary Art, a contemporary art museum operating inside a functioning K-5 public school. In the museum, there’s a confusing mix of public and private where anyone is invited to visit, but only during school hours and typically with permission of one of the museum administrators. When we invite artists to do workshops with the students, I see everyone playing. The adults are playing with expectations and materials, and the kids look delighted and surprised by what happens in the workshops. It seems like the intergenerational, playful environment is only possible through face-to-face collaboration and conversation. A very serious combination of whimsy and wisdom, freshness and perspective, listening and being heard. More often than not, our team takes cues from the kids about how to “facilitate play.”

Based on this research, I’d like to fill an entire neighborhood with sculptures of giant friendly spiders designed by the kids I work with. Each spider could have an escalator, or an elevator, or a soft sculpture ladder, or even a happy badger with wings that floats you to the spider’s peak if you’re scared. You would have to choose your own adventure, build your own platform, and you would definitely have to let the sculpture tell your story, instead of the other way around. Noguchi’s playgrounds are too beautiful, and they make me nervous—like art is going to take over the world. What I really want is for the world of a painting to spill into reality, and me and the neighbor’s mom could eat subs together in the pebbled floor where falling doesn’t hurt and the vending machine closet comes with unlimited quarters. The birthday party has no adults and kids are screaming and running until they hurt themselves on accident and everyone starts self-policing. If this could happen, WE BUILT IT TOGETHER.

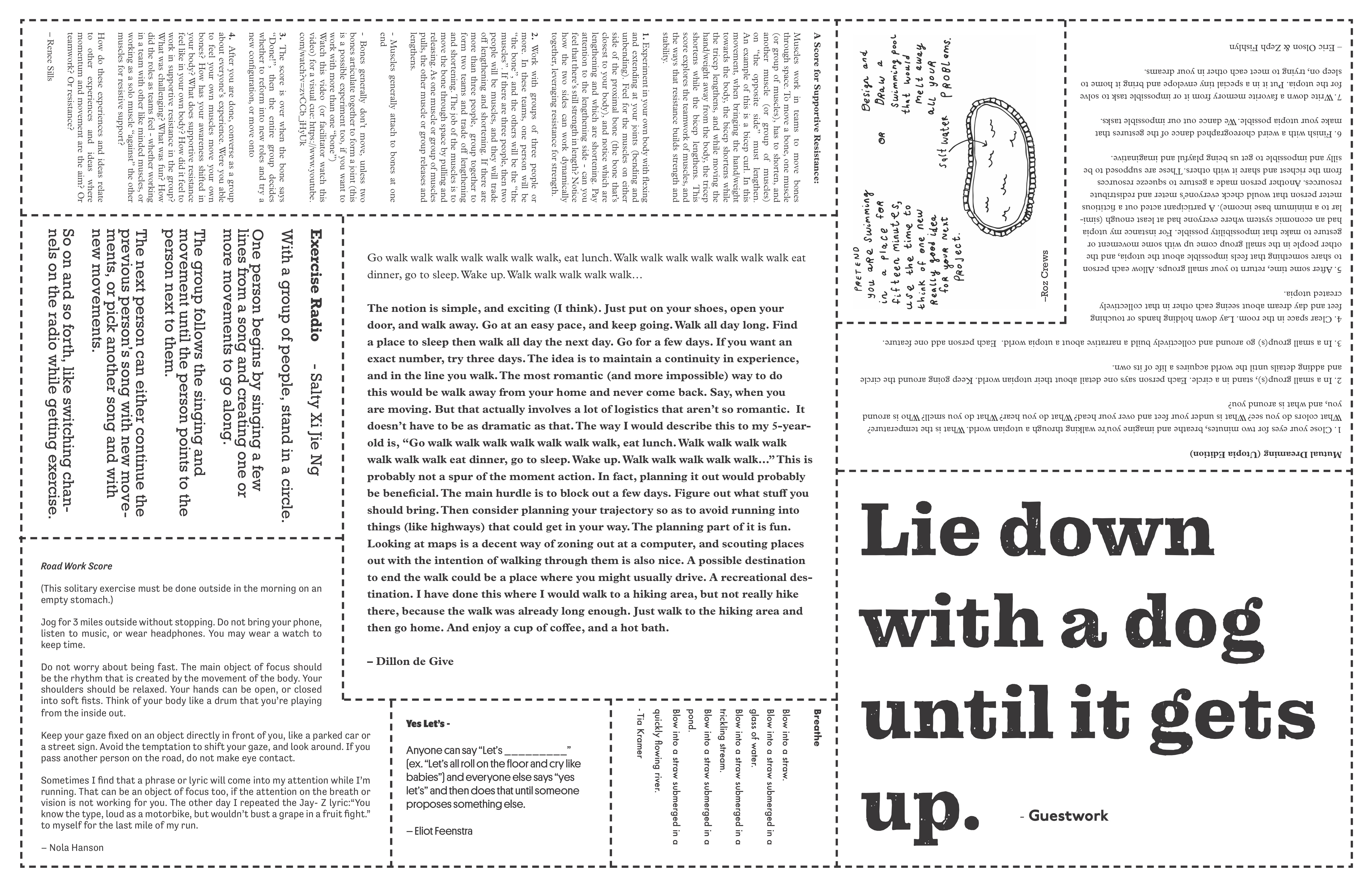

The Radical Imagination Gymnasium

Text by Patricia Vazquez Gomez, Erin Charpentier, Travis Neel, and Zachary Gough

The Radical Imagination Gymnasium is a project by Patricia Vazquez Gomez, Erin Charpentier, Travis Neel, and Zachary Gough.

In the summer 2014, we came across the article Finance as Capital’s Imagination: Reimagining Value and Culture in an Age of Fiction, Capital, and Crisis by Max Haiven. An exploration of the politics of imagination under financialized capitalism, this article raised a lot of questions for us around the ways in which our individual imaginations are dictated by market logic. We’ve essentially lost the ability to value things that aren’t measured by the dollar or monetizable. Furthermore, our imaginations are put to use by developing new ways of capitalizing on resources and exploiting others, rather than resisting such systems and imagining new ways of being together based on mutuality, care, and cooperation.

Further reading brought us to the term radical imagination, which Haiven investigates in several of his books and in his collaborative action/research project, The Radical Imagination Project. In the book Crises of Imagination Crises of Power; Capitalism, Creativity and the Commons, Haiven loosely defines the radical imagination:

“The radical imagination is not a ‘thing’ that we, as individuals, ‘have’. It’s a shared landscape or a commons of possibility that we share as communities. The imagination does not exist purely in the individual mind; it also exists between people, as the result of their attempts to work out how to live and work together.”

That is, the radical imagination is not merely about thinking differently; rather, it is the messy and unorthodox process of thinking together. The concept of the radical imagination, as we use it and borrow from these folks, is largely aspirational; it is a placeholder for the possibilities of collectively reimagining ways of being together in the world.

We began to think of the radical imagination as a group of muscles, weak and underused.

A meeting with our friend and experienced yoga instructor Renee Sills deepened our understanding of anatomy. She explained that muscles only work in teams, and when one muscle is tight, its companion muscle is slack. When one muscle is overused, it causes imbalance and chronic stress. This tightened, overused muscle causes a path of least resistance which dictates movement in its direction. That is, the more you use it, the easier it becomes to use it, and the harder it becomes to reverse the pattern of usage.

Our guiding research question became: What would a workout plan for the ‘radical imagination’ look like? We set out to develop a workout plan for the gymnasium by inviting people to facilitate workshops whose practices already embody the kind of collective imagining that our research was pointing to. The first workout was facilitated by Walidah Imarisha and centered around collective visioning, world building, and science fiction writing on issues of social justice. We designed and facilitated the second workshop with Tamara Lynne, asking participants to collectively (and silently) act out 24 hours in Utopia. Carmen Papalia led the third workout titled “Bodies of Knowledge” exploring notions of radical accessibility and involved crafting a collective definition of open access. The last workout, titled “Yoga for Commonwealth”, was facilitated by Renee Sills and used the form of the yoga class to explore ideas of collective exchange and balance.

These workouts mostly took place in Project Grow’s Port City Gallery with an accompanying exhibition. The exhibition component of this project was accumulative and included influential research, workshop generated material and documentation, as well as staging and equipment for the workshops. Prominent design features included a large scale, vinyl line drawing of a gym floor spanning the wall and floor, standard size CrossFit plyometric boxes reimagined as seating, and a combination weight rack/book shelf.

(Re)create the Radical Imagination Gymnasium

Muscle imbalance continues to feel like an appropriate metaphor for the difficulties of challenging and changing a pattern of behavior or social structure. Within financialized capitalism, we have plenty of opportunities to be rewarded and punished as individuals. What we don’t have is ample opportunity, space, and time to collaborate in the creative process of imagining new ways of being together in the world. For a limited time the Radical Imagination Gymnasium offered space for this work.

We think the radical imagination can be strengthened in the same way that a body is conditioned through incremental exercise; starting small and increasing intensity over time. What if we dedicated two hours every week to collective imagining? Or two hours a day? Could a sustained routine build enough muscle memory to reverse the dominant tendencies of the imagination dictated by market logic? We offer these questions and the proposal to continue exercising the radical imagination.

Physical Education

Text by keyon gaskin, Allie Hankins, Lu Yim and Takahiro Yamamoto

Portland based Physical Education (P.E.) is comprised of dance and performance artists keyon gaskin, Allie Hankins, Lu Yim and Takahiro Yamamoto. P.E.’s vision is to offer performance audiences, artists of all mediums and curious individuals, immersive methods of engaging with dance and performance. The group sat down for a fun and enlightening conversations about the origins of P.E., and the role it plays in each of the dancers lives.

Spencer: So to begin, I’m curious to hear how PE started? What is the origin story for the collaboration?

Silence, then everyone bursts out laughing….

Allie: That is pretty much it in a nutshell.

Lu: It started out of conversations in 2013 about wanting and needing to engage with dance and performance more critically during a project that Taka, keyon and I were involved in. We decided to start a reading group and Physical Education was the first name that came up for it. And Allie was like, hey I want to come.

keyon: No, that’s not right. Because y’all met and then I was like, “hey I want to come.”

Lu: Oh yeah yeah, so we had decided to meet, and I think you (keyon) were out of town for the first one so you knew about it but you were out of town.

keyon: no it was maybe just you two (lu and taka) and then we joined.

Allie: And it was really like: would choose an essay to read and then another one. And we would get together and talk about them, and we would also drink and eat and go off on whatever tangents. Just let it go as long as it went. And then at some point we said “oh, what if this became an open public thing where people could just come and discuss?” There is no rigid sort of way to talk about these texts, and we can just be in a room with a bunch of people. Then we got the Precipice Fund and that’s when things went public.

keyon: At its core was this thing of “come as you are,” and all levels of engagement are valid, and it was really fun. That was a big part of it too, it was super social, amongst the four of us, and kind of like an alternative criticality where we could really be able to go deep. And that was the thing about keeping it small, at first, was to not have that kind of pressure to say the right thing. Really being able to be with friends and talk shit and recognize that “I don’t know how much farther the conversation can go when the structure is so lucid and social and always so layered.”

Spencer: Were you responding to the lack of something in Portland, or the lack of something in the dance community through its inception?

Taka: I think we liked the fact that we geeked out on Martha Graham.

(laughs)

Lu: I don’t know what you are talking about.

Taka: You don’t know what I’m talking about? We were talking about martha graham, and I didn’t know much about her, but for Light Noise we geeked out on it, and we read something. And we talked about how she was a force of presentation. Something like that. Right?

Lu: Yeah yeah we naturally started to talk about the research that was behind that project. And I don’t think that was something I had personally engaged with so much in other dance processes and that was exciting.

Lu:

It wasn’t so much out of response to lack but it was more, “oh, this is nice, we need to keep this going.”

allie:

Yeah, I remember being really excited about the idea because I think many of us, when we make work, were reading a lot of material. That peripheral inspiration that comes into the picture when you’re making a thing, and just sort of just being able to process through the ways we got to different ideas. This associative thinking that often happens in making work, and often trying to read pretty heady texts around performance. And I don’t really consider myself an academic or anything like this, and so sometimes being like, “oh this is hard to read alone because I wanna try and talk through this with other people, but who can I do that with?” And this seemed like a really good opportunity to do it with people that I trust who I can ask questions around, and I don’t have to be the smartest person in the room or anything like this or already know the answers. And that’s what was exciting for me.

taka:

And keyon introduced the component about the video, not just the reading.

keyon:

It was also nice to have a group of folks that were interested in be just working, everyone was kind of thinking in other ways and some of the texts that we were using were by architects, and it felt like a group where we could really push our understanding of performance and these sort of things to allow more space within that. I don’t really feel that it really felt like a lack of Portland, I also feel like it feels very of Portland in a way. Because I do feel like a lot of times there’s more crossover between disciplines and genres aren’t so important. There’s more room to play in between them and I feel like this group was generative for me for that.

Spencer:

Somebody said, “when we went public.” What led to PE going public and how did it change the nature of the group, do you think?

Lu:

People were knockin’ on the door asking, “you have a reading group? How come I can’t come?” And we were like, “well, you can’t come because this is just something we do! ‘Cause if we let you come, then we’re gonna have to let everybody come and then we’re not gonna have this nice, intimate group anymore.” I can’t remember if Precipice Fund sort of came up and then we thought, “oh, actually, what we’re doing could really work with this grant.”

taka:

We changed it a lot. I mean, we haven’t had an intimate, just the four of us, reading group since then. I don’t think.

allie:

We had our beach week.

taka:

Oh we did. We had our beach week. Yeah, that was cute.

allie:

And I miss that dynamic a little bit. I mean, none of us are ever in town anymore anyway. It’s interesting thinking in terms of fun and leisure versus work, the way it’s gotten a bit muddy. One unspoken agreement that we’ve all had is, we’re not gonna do things if it’s not fun. But, that being said, it can sometimes be a little stressful or unwieldy because we’re like, “oh shit, this fucking deadline and I’m in New York and I’m in Stockholm and I’m in Japan and I’m in Minneapolis and who the fuck’s gonna do the Google Doc?” And it can kind of become this scramble which I think can be stressful but also it’s fine. We’re not professional. This is not a professional organization, we’re not a fuckin’ 501(c)(3), we’re not tryin’ to have this cohesive way of working. We’re just trying to make it work when it can. But sometimes it does feel like, “oh, I wish it could just be us in a room, drinking wine and talking about whatever… more… fun.”

Spencer:

I have this question around workshops in general and the idea of that form of the workshop or even the name of the group, Physical Education. Who’s teaching, who’s learning, and what has the project taught you over the years?

Allie:

Well there was a class that I wanted to do, and then Physical Education was the perfect excuse to put it out in the world as something that could be associated with reading, performance, and artists lectures. That it can exist in the same sort of realm and programming as these other things and that a physical embodiment of whatever ideas that get presented in that workshop can then lead to a different type of understanding of the other events going on around it.

So a class might be like: have a conversation about some essay, and then we also hear Samantha Wall talk about her process and then we have this artist share and then we’re gonna go get really sweaty in an aerobics class, but then all of those ideas are carried with you through that class and maybe they’ll come up or maybe you’ll think about them differently after you’re sweaty and tired. You might take your own physical embodiment of ideas to a performance that weekend that you then watch and maybe all of these things kinda can get carried through those various experiences so you’re coming to a performance with new lenses. So that was TRANSCENDENTAEROBICOURAGE. But we’ve taught a lot of different workshops.

Spencer:

I’ve been thinking about the workshop versus the formal performance, too, and how those things might relate to each other, build off of each other or be in contrast…

keyon:

I definitely feel like this group, I’ve been thinking about the name, and just over the years thinking about how things have shifted and changed, in my work, and especially in relationship with this group. I think for me, something that I’ve really been coming to a lot lately is less delineation between all of these things: between my living experience and my work, sales, and art. It’s also heinous that art, in this very Western way of looking at it, separates everyday living experience. It’s interesting to think hoow so much of what we look at are objects from the past are functional objects as well.

I think this group and Physical Education thinks about how our bodies are always teaching us and this way in which we can always be learning. Thoughtfulness and conceptuality and all of these things exist in the world that we’re in all of the time. It doesn’t have to be this kind of elite or separate kind of way of thinking about work and art in relationship to the body and embodiment and these practices. I don’t know, that’s kind of all over the place, but I do feel like this group has helped me… we talk about it as a support group sometimes. And I think there is space for all of that to kind of be in there and mix around and chew on.

taka:

It’s not just people asking me what is Physical Education, it’s the fact that I’m actually wearing a PE shirt as a form of my outfit (points to shirt). We sold 30 shirts last sale, which is kind of big but we are not making a lot of money off of it, so it’s more we’re having fun with the designs, and that’s actually what you kind of talked about?

allie:

I’m also thinking about something you (Lu) and I talked about when we were out one night. Something that happened in Amsterdam. Someone had brought you out to teach a workshop and you showed up and you did something very unconventional: you didn’t structure it like a typical workshop. And you showed up in a way that they kind of questioned you about it, like, “oh, but aren’t you going to teach them something? Aren’t you going to do something?”

We had this conversation around the notion of “you asked me to come engage with these people and I’m gonna do that and it’s not my fault that you wanted it to look like a lesson plan. I’m bringing myself and my experience to this room right now and so are they and we’re gonna go ahead and do that thing.” I don’t remember exactly how you phrased it, but something around that, which I’ve been thinking a lot about since Physical Education began. What is it to get hired to come and teach a workshop? What’s the responsibility in that? How have I been thinking about that responsibility? How have I been taking on so much… I get so stressed about the idea of teaching, because I’m like, “what if I’m not smart enough? What if they hate it? What if they don’t have a good time? I forget that just the act of showing up and bringing all of my years of experience in this field to the room with other people, there’s already so much there, there’s more than enough there, and to be able to be flexible in that environment instead of grasping on to some lesson plan for the sake of controlling the situation. I’m thinking a lot more about that in terms of teaching.

Spencer:

That idea of expectations is really rich. It’s something to play with too. And just challenging people’s expectations of anything, especially around teaching and the labor because so much of it an honorarium or whatever and it’s underpaid for what really is. I’m curious, how much space do you want PE to take up in the bigger picture of each of your lives? Where do you see it fitting?

lu:

I mean, it’s shifted a lot over the years. It’s different all the time. I was just watching this video montage of this performance that we did in 2014? thinking to myself, “aw, look, we’re babies!”

We were really actively working through ideas and trying things out and for all of us. Those things developed into what our next work was going to be. There’s something potent about that time we formed and when we started doing stuff together that has had such an effect on all of our practices that I think now when we get together it just feels different. We’re just, not so young anymore.

Hate to go there. Not that we’re old, but it is a different kind of support and a different kind of decision to come back together and keep doing things together then it was.

Allie:

When I think back to that time I’m like, “Look! Think about the potential here. Physical Education is going to become this giant, wonderful sustainable thing that’s gonna support our work and support us as friends and it’s also gonna bring a bunch of people together, and it’s gonna be this vehicle for all these things to happen all the time. There’s a future here.” And then years go by and then all of the other things that have to happen in life start to happen and you’re just like, “oh, it’s just kinda gonna look like this for now. And oh, then it’s, oh, it’s gonna look like this today…”

lu:

This is the part about getting older?

allie:

I don’t have that much time or energy anymore, but I really like these people, so I’m gonna keep investing in it in whatever way feels reasonable. I was thinking about your question of how much space do I want this to take up and I think the answer to that for me is I want it to take up more space because I want to remember what that energy felt like. But I also sometimes need it to take up a whole lot less space. The administration that has to go on around it. I’ve never been good at that, and I forget that when I have these big dreams, I’m like, “oh no no, but I hate admin work.” Physical Education’s always somewhere around here, and then every once in awhile, I’m lucky enough to have it be the focus, but it has to be super flexy.

Lu:

I love that about it. I feel like I never really had expectations at all of what it would become, although I’ve always been like, “oh, we’re doing this?! Yes! Sure!” It’s this fun, mad, flexy thing.

keyon:

It feels like it does take up the amount of space that we have capacity for. So sometimes it is smaller, and it isn’t happening sometimes because we don’t have the capacity. But I like that, I think it is a different thing that keeps bringing us back together but I do really like these folks. I love the stuff we do and it still feels like a space that even though it’s a very different way of pushing back or doing things. Think about the works we did at Composition. How different, and similar. But it is still pushing, it’s still a generative ground. It still feels like a generative playground in that way.

lu:

Things always happen when we come and do these events and spend a substantial amount of time together in a space–it feels like a magic. Sometimes trouble comes through and we’re not quite sure what’s gonna happen. We better be ready. This time there better be a nurse practitioner in the audience-

taka:

Everybody knows that Physical Education is something that we do, but we are not of it. I was thinking about it. It’s like, “remember Allie of Physical Education?” And nobody’s gonna say that to us. So this entity is so interesting because the sense of belonging is so not, it is a part of our life.

keyon:

I kinda like the idea that everybody’s in Physical Education, whoever is engaged with it. Maybe we’re the little nucleus or something that’s keeping it going or maybe the heart of the thing, but everybody engages, you’re always kind of a part of it.

Spencer:

Well and it’s definitely kind of a lens, I think, or a method of thinking that once someone understands a lens, they can then apply it whenever. It’s like that idea, there’s new ideas around exercises or it’s actually any steps or exercise or going up the stairs once is technically exercise, so you can kind of claim it in that practice and extending that to art I think is really empowering to say, “actually, this is performance, or this is an artist’s practice, even if it’s just sitting in a room and talking or something.”

allie:

Or microdosing on mushrooms on the coast in a cabin.

Lu:

Yes. In a wetsuit.

allie:

Wearing a wetsuit.

keyon:

Those fucking wetsuits.

Guns, Money, Mud, and Play

Text by Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr. and Katie Shook

By Artists Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr. and Katie Shook

Katie and Michael are both artists, and both have practices that involve working with children. So questions about what play is and how play in childhood transfers to adulthood, and to an art practice, are central themes for both of them. Does play in childhood inform one’s interests and pursuits as adults? Does making art for money make art less altruistic? Do violent toys lead to violent behaviours? Is the making of art inherently correlated to play?

Here are some ideas they gathered in response to these questions and others paired with photos drawn from their respective practices and beyond.

PLAY AND ARTMAKING

Children playing in the mud at the Adventure Play Garden, run by the non-profit Portland Free Play. Most people over thirty have memories from childhood of playing outside without adult intrusion. These days, kids don’t get as much time and room to roam, free from an adult agenda.

Katie:

Artmaking really depends on the ability to take the time and space to get into a creative frame of mind. Everyone works differently, but for my practice, I find I need several hours uninterrupted to get anything constructive going. It’s harder for me to get to that place when I’m stressed and feeling under pressure. Creative thinking and the flow state are akin to play, resembling the mindframe that children get into when they are given unstructured play time.

Children deserve time for free play, just as adults have a right to pursue their own intellectual and creative interests.

It can sometimes be hard for adults to see a child’s play time as valuable, and not impose some expectation for learning or performance. There is inherent value in what a child wants to play at according to their own motivation, but the special secret about free play is that children are actually learning and developing on very complex and nuanced levels, often far beyond the outcome of a traditional classroom.

Adults who watch children at play sometimes interpret their actions and intentions inaccurately. We see children’s play through an adult lens, influenced by our history and adult motivations. One way to find out about what kids are playing at is to observe and listen. It can be intrusive to ask kids to explain themselves. And also, I think when kids are in a deep play trance, their experience can be outside of language and putting words to it.

Reflecting on my own experience of art making or being in a state of play, can I put that into words? Would others be able to understand my experience? Sometimes my most satisfying feelings while making art aren’t about ‘fun’ really, but about feeling a drive, or a sense of compulsion. Michael, you’ve used the word ‘compulsion’ in describing your artmaking.

Elijah and Michael open for business at the Totally Honest Bazaar during the Schemers, Scammers, and Subverters Symposium

Michael:

In some of the work that I’ve done with Elijah for Well Made Toy’s㏇, and in other Imagination Academy projects, there’s this imaginary or imaginative premise that then gets actualized in a playful way. Where the rules can change and there’s feeling highs and lows, there’s discomfort with engaging strangers outside the game who’re being invited to play. However in Well Made Toy’s㏇ there’s the fun and exciting pay off to playing the game, actually selling a toy that was made for the game.

The socio economic dynamics that surround the exchange of goods for money are complicated, emotional, and hardcoded into our culture. These things are challenging to understand and navigate for adults, but through gamification of capitol exchange young people can participate and learn from a safe and constructive method of engagement.

PLAYING WITH MONEY

Joseph at the 2017 KSMoCA International Art Fair shows off an artwork to a patron that later resulted in a sale

Katie:

Some recent research has found that kids behave more selfishly after playing with money, real or fake. (See the story in Pacific Standard magazine here: https://psmag.com/social-justice/handling-money-decreases-helpful-behavior-among-young-children ) The act of handling or playing with money results in a decrease in generosity and prosocial behavior.

What happens when we introduce the notion of selling artwork that children make – does the introduction of monetary exchange alter the creative experience for children? Does money change the act of creating for adult artists as well?

It’s curious to think that the materials we provide for children in play can actually prompt very different kinds of behaviors, emotional experiences, and levels of human connection or disconnect. Our choices in the environments we design for children may have greater implications than we anticipated.

Artwork by DeAndre at the KSMoCa International Art Fair

Michael:

In the first KSMoCa International Art Fair, Michael, one of the youth participants, was paired with well known and renowned artist Christopher Johansen. Together they made a few drawings using a pastel color palette. They were listed at $200 a piece and began to sell quite quickly. Other KSMoCA participants saw this capital enterprise and became enthralled by this commercial exchange. They quickly started making drawings and listing them at 10, 20, 50, 200, and 500 dollars. One of the minimally vocal youth scrawled his pricing structure onto an amazing drawing of transformer characters, “20 or 15$ if transformer fan, 5$ I mean it!”

Elijah makes a sale of a Well Made Toy’s㏇ toy

When Elijah and I began setting up for this project I let Elijah know he could set the prices for the objects we were selling. All the toys were made by him and his peers, they were quite simple but elegant and had wonderful pops of color accentuating their preexisting features. I had spent quite a few hours making custom mounts for each toy from some beautiful reclaimed wood. Elijah said “let’s sell them for $7 each!” I was shocked as selling them at that price wouldn’t even cover the cost of materials much less labor. However the goal of the project was not an in depth understanding of economics, so I agreed. Later after making a few hard earned sales, a more confident youth from the Living School came over to Elijah and offered him a photo copied single page zine for $10. It Seemed Elijah contemplated this for less than second and agreed to pay the price. I was shocked again, the premise of material and labor value was totally subverted, the desire for exchange was greater than any other criteria. As the money was his, I pulled $10 out of my pocket and handed it over, and continued to look on with amazement as Elijah handed the money over much more easily than anyone had for him.

TOY GUNS AND COMBAT PLAY

“Toys” in Michael’s collection of objects poised for future projects

Katie:

Children learn positive social skills through play fighting. In combat play, children learn negotiation, empathy, how to read complex facial expressions, and assess boundaries. This can be playing with swords, sticks, toy guns, and rough and tumble play. Dr Stuart Brown’s research has shown that this kind of play reduces violence in adulthood. It’s important for children to have access to all kinds of unstructured play time, including playing at fighting.

SOCIALLY CHALLENGING PLAY

O’Donnell proposes that working with children in the cultural industries in a manner that maintains a large space for their participation can be understood as a pilot for a vision of a very different role for young people in the world – one that the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child considers a ‘new social contract.’

Michael:

In any artmaking, but especially in socially engaged projects, there is the potential to push boundaries that begin to protrude awkwardly and ambiguously into the cultural contexts in which they occur. I often wonder what can we do playfully as adults that challenge societal structures, social norms, the status quo? Again, with any artwork, through viewing or participating one is being asked to understand a complex idea or set of ideas architected by the artist/maker. This form of expression is often attempting to create a dialogue between the work and those experiencing it. This is much like an invitation to play.

When this paradigm within art is extended into a social space, a simple subversion of an ordinary thing may cause participants to extend their comfort zone beyond the ranges in which they are currently held.

____________________________________________________________________

Links:

Preschoolers and gun play

http://teachertomsblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/gun-play.html

Old fashioned play builds skills

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=19212514?storyId=19212514

Penny Holland research on gun play

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2003/jul/12/schools.uk

An Interview with Jen Delos Reyes

Text by Spencer Byrne-Seres in conversation with Jen Delos Reyes

Spencer:

So for the third issue, I’ve been interested in this idea of recreation. I’ve been thinking about projects that are recreational in certain ways either through using forms of play or relaxation or leisure in what they’re actually doing. From there, I got more into this idea of what does recreation actually mean to artists? Are artists, on some level, always doing both work and leisure? As an artist, the assumption is that you’re doing what you love.

I wanted to start there, thinking about your book I’m Going to Live the Life I Sing About in My Song, and thinking about that idea of an artist’s life, and what that means. Maybe you would want to talk about the genesis of that book and how it came about?

Jen Delos Reyes:

For sure. In the intro to that book, I talk about hearing this song for the first time when I was in graduate school, which was written by Thomas Dorsey and performed very famously by Mahalia Jackson. She’s singing clearly from a voice which is her own, but a perspective which the listener could read as the space she occupies in her life. The song is about a gospel singer who is talking about the fact that in her work, her craft as a gospel singer, that she can’t sing these beautiful songs and then live a life that doesn’t feel like it actually upholds the art that she’s putting in the world. The refrain is that “I’m gonna live the life that I sing about in my song.” That felt like a complete revelation hearing that in grad school, and saying, “Yeah, actually 100%. I want the exact same thing. That what it is that I do in the world as an artist, I want it to be completely in line with my values, all my values. And my life practice.”

I guess it was at that point that it really felt like it was a goal. It felt like something almost impossible in some ways. It was definitely in my mind from that point on. I think it’s hard to disconnect that too, especially when, as an artist, a lot of the work you do is about lived practice, lived experience, and being with others in a lot of ways. I think that was really the first seed of that project, and I didn’t really realize it at the time, other than just having this general admiration for that way of living and working, and that connection to what you do in the world, especially as an artist. I also mean that for everyone. I don’t think it’s just for artists at all, to be able to live in that way.

Fast forward years later, half a decade later, and I’m invited to do a residency as the Hyde Park Art Center in Chicago. I’ve been working with this great coordinator there, she’s fantastic. I’m actually really struggling with what I want to do at this residency, like what is the frame for it, what is the structure? At one point she asked me, “Well, what could you do, or what would you do if you could anything? If you could really do anything, what would you do?” My sincere almost immediate answer was that I just want to live. I meant it, but I meant it in this way that I was I want to live with intention and with value, in the vein of I’m Gonna Live the Life I Sing About in my Song. It ended up that I started using that residency, which I think was in 2013, on doing research into intentional living, intentional communities, and utopian impulses. Groups like the Shakers, for example. Other groups in the US, especially that were easier to research and very possible to even visit.

In particular, I wanted to connect those sorts of groups and impulses to artists who are clearly inspired by some of those radical approaches, or different ways of being in the world, and with each other. That came together in the form of the book. In a lot of ways, I feel like the book is a failure. It is an interesting series of cases studies of artists who I really feel do justice to that Mahalia Jackson song. They’re people whose work I admire greatly, I also admire them as people, and what they have set up is incredible and completely inspiration, and so different. The main people in the book were J Morgan Puett, and looking at Mildred’s Lane, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, and looking at the work she did with the New York City Department of Sanitation as the official artist in residence. Then Ben Kinmont and his Antinomian Press, and his work as a bookseller. David Horvitz, and I just feel like everything in his practice is so just emergent from his personal life and relationships in this really beautiful way. And Fritz Haeg, and his embodied practice, but it’s also his communal practice and how he builds community, especially for artists.

All of these people were inspirational for me, and in very different ways. I showed a lot of examples of how an artist could be in the world. Basically everything I described in terms of their primary activity is not necessarily what most people think of as art: like running an art school in your home or starting a bookstore, or foraging for mushrooms, or whatever. All of these things aren’t necessarily the things that we think of when we think of artists, but they’ve been able to structure their lives in a way in which that is something that they get to do. I had hoped and intended that the book would serve as a roadmap for anyone to be able to take inspiration from that and do it, but the truth is, it doesn’t feel like that and it doesn’t read like that.

It’s fine, because in life, there are always more opportunities, and I feel like that to me, has then given birth to this new book that I’m working on that I actually feel will do that thing that I wanted it to do, that is about like, well how can we all live lives of meaning and value and look at our daily activities, and really keep them in connection to what is happening in the world, and not separate them because we are in a moment of social crisis, economic crisis, environmental crisis. We should all be crushed under the weight of how horrible things are in the world right now.

Spencer:

I’ve been reading your lecture What We Want is Not Free, which mentions all of the unpaid labor you put into Open Engagement. I think dovetailing with that, I’ve been thinking a lot about labor, and how normally we have to do stuff that we don’t want to do because it’s what pay the bills, or it’s what basically helps you survive. How do those two things relate to each other? There is this balance between precarity on the one hand, and utopian aspirational values on the other hand. Where do those two intersect, and how do we shift from one to the other?

Jen Delos Reyes:

What a big question. I feel like I have so much to say about that right now, that I’m a little bit like, “Well, where do I start?” One of the first things I’m thinking about is this idea that … and this is a little bit like some of the feedback I had gotten from the I’m Gonna Live the Life book, this idea that to be able to operate in the way that these artists operate from, is a privileged position. That not everyone gets to make these choices and to live in these ways. Which isn’t necessarily wrong, in a lot of these cases, there are instances in place or structures in their life that allowed them to do work for free. Here’s a great example: when I was talking to Mierle Laderman Ukeles, I asked her, “How were you able to be the unpaid artist-in-residence for 40 years?” The reality is that her husband, Jack, helped to support her and make that possible. I think that there’s just not enough transparency around economics, around the problematic structures especially in the art world, around class and privilege that people don’t talk about. This makes it possible for certain people to do unpaid labor, that then helps them to get better jobs within the system.

Let’s talk about unpaid internships. Those are very privileged positions, you can’t be someone from a struggling economic background and think that you can do an unpaid internship and live in London or live in New York or in LA doing this great internship with the Getty or something, and just be able to live. Think about the amount of privilege that one needs to have to be able to do that. When I would talk about, and this was actually with that same amazing residency coordinator, Megha Ralapati. That I was, “Talk about how I want everyone to be able to take inspiration and live these lives, like their lives, with integrity and with purpose and to have a life philosophy that guides what you do in the world.” She’s like, “That feels so privileged. What about the people who are working these jobs that they can barely pay their rent, there’s so many unpaid bills. There is a way in which some of the models, the case studies are not feasible for most people, but I think what is actually possible is that we can still make small and micro decisions within our lives that are within our value structures.

It might not just be on the same scale, but it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t do that because I do believe it will still have an impact. For example, here’s one that I actually think works with this okay, well economic pressing matters of daily existence. Someone like Fritz Haeg is very critical of fast fashion and over consumption, and is someone who’s making and knitting their own clothes. That is not a thing that every single person can do. One, because maybe you might need to gain that skillset, you never learned how to sew, or you don’t have the hours and hours and hours it takes to be able to sew a garment, or knit something. But, you do have the ability to say, “Okay, I do not agree with the exploitative labor practices of fast fashion, and I don’t want to go into one of these chain stores and buy something that I know is basically made by someone who is not even paid close to a living wage, is essentially a slave in another country, and be a part of this chain.”

What can you do to actually stop that cycle? One, you could not buy new clothes. It would actually be cheaper for you to go to a thrift store, to go to a Goodwill, to buy clothes in that way. Everyone would be better served if they also had a better understanding of who they were as an individual and what they wanted to communicate in the world, and not be so seduced by advertising, honestly, and current trends because then you’re in this other cycle of trying to purchase things that will make you feel a certain way because it’s like you haven’t … this sounds so new-agey, but I think it is part of it, like that’s a lot of the inspiration behind some of these artists that I’ve been so enamored with in this book. It’s about actualization. It has a little bit to do with actual knowing yourself and what that means, and then your messaging. I actually think that it would be such a radical act if people took aesthetic control of their lives in the same ways that artists do, and would define what it is that they put out in the world in a daily, every day way.

Spencer:

I wanted to pull back for a second and go back to this question of how do we quantify the work we do as artists? I wonder how we cash in on this work we do just to survive in the first place.

Jen Delos Reyes:

Oh my God. Okay, thank you for bringing us back to this survival question ’cause it got lost in that storm of soap box passion.

I’ve been thinking about this book by Julie Rose called Free Time. I don’t know if you’ve read it, it’s pretty remarkable. Her position is just not one that I had ever heard before, but it made so much sense. She’s framing free time as a social justice issues. She’s says, “The same way we think about the distribution of wealth and resources, we need to think about the distribution of free time.” It gets very complex in terms of how she defines free time, and how that’s measured. It’s a beautiful book. I can’t recommend it enough.

Then it’s like, how do we think about our work as artists? I definitely want to answer that question. You already have a little bit of insight into where I’m at in terms of a position on free labor and needing that to shift. How do you even look at all the problems around being an artist and labor? One, I’ll say that in this country in particular, there is this expectation that artists will work for free. That we are not valued, like people are not valued who are artists, but art objects are. I’m like, “Can we get that to shift a little because if you don’t care for the people who make the work, then you don’t get those beautiful objects or experiences.” Part of caring for artists is actually being able to pay them a living wage.

I guess I don’t like the framing of how do we cash in, or capitalize? Because those reinforce problematic structures of capitalism that I wish we never had. I think it takes radical imagination to be able to think differently about what those governing structures are. Let’s not go into fantasy world. Although, I do think that science fiction and fantasy are very important because it does get us to exercise our muscles and think about other ways and other worlds, which I think we desperately need. We do live under capitalism, we do need to survive, so how can artists ensure that they are paid for their work?

Look, in our world right now, there are actually countries where this happens already. I am like, “Hi, I’m from Canada. We have CARFAC, artist run culture, artist led culture fought for this, and then it became government sanctioned.” Now this is the set regulation of how artists are paid for all their labor, and it’s incredible. It breaks down what an artist should be paid for a workshop, for an artist talk, for a group show, for a solo show, for a write up in a publication, for this, for this. It goes over all these different forms of labor, and then it says like what the percentage rate should be. Then the great thing is that it’s scalable, so it’s not just like an institution looks at it and they say like, “Oh, that’s a shame ’cause we don’t have $1,000 in our budget to be able to pay for a workshop.” It’s scalable in that what the artist is paid in based on what the annual operating budget is of the institution. If it’s a bigger institution, then you get paid more. Then also it’s a pay range based on if it’s a solo show, you get paid more than if it’s a group show. Just all these things that take into account how much labor is expended and how an artist should be compensated.

I think that we need a system that is more like that here. People need to operate in that way. There are amazing groups like Wage, who are advocating for those sorts of structures. I think it starts, also this goes back to this, “Oh well, it doesn’t matter. These systems are so strong, the institutions are so strong. I just have to do it.” I’m like, “No, actually, you don’t. You can bring up for yourself as an individual, as an artist, what your value is, and the fact that you can resist. If an institution is not going to pay you for you work, you can say, “thank you, but I actually have decided to make a choice in which I no longer give my time for free. This is not free.” I guess I’ve gotten to a place of deep frustration around that, and that has come out of years and years of free labor and being exploited, honestly, by large institutions and doing work that no one really told me that I shouldn’t be doing, or that should be only the work that a full time tenure track or tenured faculty does, that’s not your work, you don’t do that ’cause that’s not paid. You’re just adjunct, you’re responsibility is just that one class.

Then we get so, I don’t even know. I think that yeah, it begins with artists actually making demands and then resisting institutions, and calling out and calling in institutions to be able to join and to make this right. For me, part of how I’m making this right is that Open Engagement should actually be a model of sustainable artist led culture. I do not want to do any work anymore for Open Engagement in which like if we were to be transparent about it, and you were to see the inner workings, I want to feel good about it. I don’t want to feel like, “Wow, we really modeled a piece a shit.” No one needs to be working for free. That’s not what I want. Why would we model that? I want us to be an example, and I want us to show larger institutions that these changes actually can be made. Part of that change is valuing artists for their labor.

The other thing too, is like I don’t know, this like, “Oh, well, you could commodify the thing that you do in your life that brings you joy and does this thing, and sell it to an art institution.” Yeah, you could, but you could also just do it for yourself and for your life. I do a lot of these things that yeah, I guess I could do that as public programming somewhere, but I’ve just made that choice that it’s like, “No, I don’t frame it as ‘this is an art project.’” It’s just part of my life practice. I think that that is actually important for us to be able to do, that you don’t have to commodify everything in your life. You don’t have to make everything a project. I think that’s part of what we need to model, maybe as artists for other folk, is that it’s like we can just do these fun and creative things, and you don’t have to call it art. They can just be like what you do because it’s what you want to do in your life.

Spencer:

Yeah. It gets so confusing. Thinking about transparency around boundaries, too. The willingness to say that even if something looks like an art project, to say like, “This isn’t art. Or this is just part of my life practice, I’m not trying to think about this in terms of that bigger, that labor piece, or something.” And setting boundaries where you are able to not so much clock out, but check out from thinking about the thing … or check out from relating to the thing as labor because ideally you want it to be a source of strength, inspiration, resiliency, fun, any of these other things also.

Jen Delos Reyes:

Oh my God, yes. I’m happy to hear you say that because part of the definition of recreation is well, one, you can look at it as like re-creation too, to make a new, to do over. It’s like this practice that’s a constant re-creation. Then it also is supposed to be restorative and revive, that that is like it when you break down the definition. It’s from these words that mean those things. It’s like it is something that we need to do for ourselves to I think, be able to do the work better. It should not be seen as frivolous. I don’t think it’s frivolous. It’s like insert Audre Lorde quote here about self-care being a form of revolutionary practice. It’s guerrilla warfare in a way, because if we care for ourselves, we can do that important work in the world.

Spencer:

Yeah, and it’s only frivolous in the capitalist lens of the important thing is the work, and then the free time is where you get to mess around and do whatever you want. That speaks to a lack of intention, where you’re not thinking about either necessarily, in a very wholistic way.

Jen Delos Reyes:

Yeah.

Spencer:

I just had one last question. What do you like to do in your free time?

Jen Delos Reyes:

I wonder if part of this is about a mind shift, just that even to say like, “Okay, well there is a certain amount of time that is “free time”.” Maybe that’s not even the best way to look at it. I often think about this Annie Dillard quote that has been something that helps guide what I do on almost a daily basis, and was thinking about it even this morning walking to work. The quote is also so simple, you’re like, “Yeah, I know. That’s basic math in a way. That’s basic time math.” What Dillard says is that what you do every day, every hour, of course becomes how you live your life. To think about all time as being equally important and how your life is lived.

I do try to have everything feel values aligned for me, and part of that is why am I here at this job right now even? I’m here because I believe in this mission of urban public research university that it is a majority minority, and it is about access and the most affordable education possible. That that is important to be here and to support that. Or-

Spencer:

On spring break, no less.

Jen Delos Reyes:

Yeah, on spring break, no less. I don’t know, I guess I’m just trying to think of all time as so valuable. The other thing that I’ve often said, now I can’t think of who said it, is that time is the most valuable thing we have to give each other, and that that is so meaningful. I guess I try to think very intentionally about how I spend all my time, not just the time we like to think of as free time. I want to be able to look back on my life or have other people look back on it, and for there to feel like there was meaning and purpose and value in all of it, in all of the time that was spent here and with other people.

The Portland Museum of Art and Sports

Text by Lauren Moran and Anke Schüttler

The Portland Museum of Art & Sports was located at Portland State University’s Rec Center. An institution within an institution, the museum was founded in 2015 as a dynamic space dedicated to the exploration of two subjects that are rarely paired together: contemporary art and recreational sports. Through installations, events and programming that showcased local to international artists the museum explored unconventional situations for engagement to activate the spaces where art and sports intersect. Anke Schüttler and Lauren Moran, the founders and curators of the museum, reflect on the process of bridging divides, pitching art projects, and recreation in art.

Photos by Anke Schüttler

Lauren: We were talking about recreation.

Anke: Yes, I realized that both sports and art can be seen as a means of recreation.

Lauren: For most people, yeah.

Anke: It’s funny because when we were thinking about this museum we were saying sport and arts do not really go together so well or they are usually not seen together, though there is this connection that I actually have never thought about before. And also ironically when we were talking about doing this project at the rec center, we were both saying ‘I’m not exercising a lot at the moment and maybe that’ll get me into exercising more’ and then we actually never got to it really.

Lauren: Yeah, we were so busy working on all the projects and installing all the art and working with all the people at the rec center that we left out the recreation part.

Anke: The fun part… I mean it was also fun to do the project obviously. Earlier I was asking you about your relationship to art and if you would think that art is a form of recreation for you?

Lauren: When you said that it made me think of how it’s probably just as likely to be a famous artist as it is to be a pro sports athlete. They’re probably both as rare, but I’m sure athletes make more money.

Anke: And also probably they wouldn’t say “yes, I do sports for my recreation.”

Lauren: I would do art for my recreation. Right now I don’t think I would do social practice art for my recreation. My recreational art is making things out of clay.

Anke: Oh, yeah. Me, too. Thanks for reminding me!

Lauren: Forms of art I find relaxing are not the kind that I do for my work lately. It’s a little too much like a real job now. I actually started off this year thinking about this topic, maybe recreation or our discussion last year about what you would do for fun and how you could make it into a project? When I did the karaoke project here, or a walk in the woods, various things, sometimes it started to feel like work and I’ve been contemplating that. It was fun, it just felt like the expectations were different … And also I wasn’t consuming it. I was creating the experience, which is a lot more work.

Anke: Yeah.

Lauren: Anyway, exercise and sports is something I was always an observer of and that continued with our project. We were looking at it through this conceptual lens.

Anke: I really liked how this serendipitously came together, being offered the residency at the Rec Center. We went to have a look at what we could do there and while walking around you pointed out how this looks like a museum building-

Lauren: Right, it felt like a museum tour.

Anke: Yeah. I really liked that and ever since you said that I thought “for sure, there are so many aspects to that building that have a similarity to a museum.”

Lauren: Yeah.

Anke: The concrete walls and all the coloring.

Lauren: I wonder if a sports person would go to an art museum and be like ‘oh, you could really play basketball in here.’

Anke: That’s such a funny idea, yeah.

Lauren: It’s interesting to come at non art things from that lens of everything is you know-

Anke: An art space.

Lauren: Yeah.

Anke: I definitely have that lens a lot and I really love that.

Lauren: Me, too. So that’s how it started. We took the tour and we were like “Oh yeah, this is like a museum tour. What if we make it into a museum?” And then we-

Anke: Slowly took it over.

Lauren: Slowly developed these personas, right?

Anke: Yes, thinking about our role and deciding that we were both co-directors and co-curators for the museum. And when I started having that as my signature in my email people from Germany were like “What? You’re a director of a museum now? That’s so cool.’ I really love how that took this extra turn that I didn’t expect at all.

Lauren: I remember Harrell even saying, “you know, PSU doesn’t have a museum yet. Now it’s getting one, I guess.”

Anke: True.

Lauren: So we were really asking what do we do as museum directors and curators … in this museum that we just decided was a museum?

Anke: Yeah, and finding all the artists was fun, thinking about the artists we know that work in that intersection between art and sports. It’s exciting how many things we found and so many different, very diverse works.

Lauren: Right, at first we thought these topics don’t have a lot of overlap, but then we found so many overlaps.

Anke: I really enjoyed when we were taking care of where the art would be, relating the art to the space. That’s a thing that you can’t do in a museum because the museum is just empty and without any personality before you put the art in, and I think that made this project so strong for me.

Lauren: Yeah, yeah.

Anke: Like putting the work that Adam Carlin did about lifting heavy things into the weight lifting room or –

Lauren: The videos with the ping pong balls with the ping pong table. That’s a good point. If it was just a regular museum we wouldn’t be able to make those connections at all.

Anke: And then some people got really into it even though they’re maybe usually not into art or wouldn’t go to a museum, but suddenly they got really excited about the work being at the rec center.

Lauren: I think that happened a lot. With the art and the context, I think it worked both ways. Sometimes we asked:’What can we fit into the space?’ and then sometimes we would find the artist and decide:’ this art would fit perfectly here’.

I think about how combining the two things or maybe inserting the art and deciding it was a museum in a non art space, when we gave the tour it just had this amazing sense of magical realism, you know? That was really special. I always try to seek that out in projects and that was one of the times I feel like it was really successful. Especially with the water dancers in the pool…

Anke: Or the runners…

Lauren: Yeah, with the treadmill pieces.

Anke: Yeah, the treadmill pieces were amazing.

Lauren: And just everyone being active in the space, doing their thing at the gym.

Anke: Activating it so nicely without the intention of activating it. That was very magical.

Lauren: There was definitely just a magic to that that I can’t quite put my finger on, but I feel like I learned a lot from.

Anke: I guess it goes both ways, right? Because it’s an already active space, the running would happen with or without the art, but it’s funny when then you have someone coming in for the art and wanting to look at the art, and they obviously also have to look at the runner in front of the art. Suddenly you end up with this combination of something that’s intended to be art and something that’s just an everyday life activity but in that context you cannot separate it from the rest. You cannot not see the runner in front of the art.

Lauren: So it just becomes all part of the experience.

Anke: It’s sort of like we were seeking out the side noise, which in more traditional art is usually excluded, right?

Lauren: That’s interesting because if all the stuff had just been in a blank space it would have been way less interesting. It needed the people around it to be fully experienced really. It just needed the place itself.

Anke: Right!