Category: Winter 2023

Cover

Text by Luz Blumenfeld and Gilian Rappaport

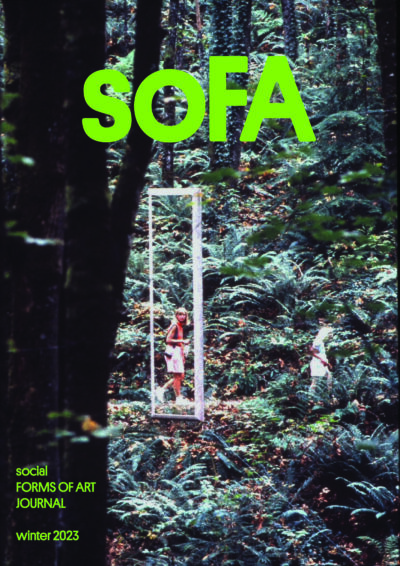

Tim Warner frame installation in ‘Finding the Forest’. Conceived and Directed by Linda K. Johnson. 1991. Forest Park in Portland, OR. Photo by Julie Keefe.

It’s technically March at the time I’m writing this, but here, in Portland, it still feels like winter. I miss the actual sunbeams that used to hit my kitchen floor in the winter in Oakland and how my cat would stretch out her body to fill the whole space. This image feels like summer to me and reminds me of sitting in a fairy ring of redwood trees. I think sometimes you need to bring the sunlight and warmth into the winter, so maybe this cover will do that for you as it did for me. Some other words we associate with this image are: physicality, grounding, ferns, nature, firs, and “feltness,” which Gili talks about in their interview with Linda. The “Finding the Forest” project depicted in this image brought people together in physical space in a way that feels so distinctly pre-pandemic. As our campus reopens in real time and space, we are excited to make new connections with our greater PSU community. You can see some of these connections in this issue of our Social Forms of Art Journal.

-Luz Blumenfeld and Gilian Rappaport

Letter from the Editors

Text by Caryn Aasness, Luz Blumenfeld, Becca Kauffman

For this issue of SoFA, we each interviewed people affiliated with Portland State University. Our social practices tend to engage with communities, but as a program we operate more as a satellite of our parent university. Individually, we have our own ways of connecting with campus life— teaching assistantships in undergraduate classes, working on-campus jobs, hanging out in the park blocks, taking Dance Fusion aerobics class at the athletic center, or working in the Social Practice Archive housed in the Special Collections at the PSU library. But because we primarily convene for classes off campus— at KSMoCA (Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School), Harrell’s living room, on Zoom from our respective homes (or favorite coffee shops)— it can feel like we, as a group, are disconnected from our university community.

This year, as we experience a completely open campus after an era of pandemic protocols, many of us are getting reacquainted, or acquainted for the first time, with our campus; sprucing up our studio space, doing projects at the art department’s Open Studios, or picking up free groceries from the food pantry in the basement of Smith Student Union.

This winter, we found people in departments all over PSU who are engaging with topics connected to our own areas of investigation. We are excited to introduce you to the many people doing incredible research, teaching, projects, and labor across the university.

In the interviews that follow, we meet a dance professor who wants you to notice your body in the city and the city as a body; a pragmatist philosopher who surmises the whole world is one big role playing game; the lone mascot of PSU’s athletic department who’s willing to shake everyone’s hand; a sociology professor who wants us all to talk more about death; a social psychologist devoted to trash; two graduate students with an intimate connection to their bowel movements; a critical feminist geographer using comics to explore the experience of homelessness; a critical race spatial educator uncovering the hidden curriculum within university culture; and the PSU Provost, who wants more artists’ voices in the room.

Come with us on the most in depth and strange virtual campus tour you’ll ever get!

Your editors,

Caryn Aasness, Luz Blumenfeld, Becca Kauffman

A Space of Belonging

Text by Marissa Perez with Dr. Kacy McKinney

“I was invited into this space with these people who are all deeply caring and deeply welcoming and they told me, you belong here and your art is good enough and you are good enough and we need you.”

Dr. Kacy McKinney

I first met Kacy McKinney in a classroom at a small college in rural Vermont. She was a professor in the geography department and I was a student who didn’t know what I was interested in so I took my friend’s advice and took Kacy’s class about GMOs and was so glad I did!

When I moved back home to Portland in 2017, it felt like Kacy was appearing everywhere I went. First, at Sisters of the Road, a community space and cafe for the unhoused community, and then at the Independent Publishing Resource Center (IPRC), a community art studio, where I was a front desk volunteer and Kacy was a student in their comics program. And then again this year when I started this program at PSU I was delighted to remember that Kacy is a Professor in the Urban Studies department and we can continue to run into each other.

Kacy is the facilitator, instigator, coordinator of “Changing the Narrative,” a project that “produced a series of ten short comics created through collaborations between PSU students with lived experience of homelessness, Portland-based comic artists, and the research team” that culminated in a book of comics sold by Street Root vendors on the sidewalks of Portland. It was a pleasure to talk to Kacy about this project that brought together ideas and people from the two places we encountered each other in Portland.

Marissa: I think it would be fun to start with how when I moved back to Portland you just kept popping up. I saw you at Sisters of the Road– I saw your picture on the board members list, and then I started volunteering at the IPRC and I was like “Oh, there’s Kacy again!” It was so fun.

Kacy: And I think the funny thing is– you didn’t ever take a class with me at Middlebury, did you?

Marissa: No, I did!

Kacy: You did? Okay. Which one did you take?

Marissa: I took Political Ecology of GMOs with you!

Kacy: Okay, cool. That was a hard one. Nice. I was trying to tell Sage, my partner, last night, and I was like, I think maybe she never took any classes with me. We just were following each other in Portland, but that’s a good class for you to have been in anyway.

Marissa: I was glad to be in it!

Kacy: Did you live in that house too? The house that everyone lived in? With the food?

Marissa: Yes! I lived in Weybridge.

Kacy: Yeah. That’s where I would’ve lived if I was a student there too.

Marissa: I wanted to start with how you feel about where you are now as an educator and also as someone who is in the comics and DIY world? And how you feel about how you got here?

Kacy: My path through education began with not going to high school and instead I took a test. So I had this different way of doing school and I did finally start a four year undergrad at University of Texas because I wanted to learn Portuguese really well. At that point, I didn’t have that many people in my life who were excited about education or who wanted me to do graduate school or anything, so I just followed models around me and it was very, you pick a discipline and you do the discipline and it’s all social science, and I was drawn to that. So even though I had art and creativity in my life (I was even making comics then), I didn’t take it seriously because nobody around me did. I sort of moved through undergrad and then into a master’s and then into a PhD, all the while being like, someday I’ll have time for art. Someday I’ll have time to volunteer and do service. And by the time I got to Portland I’m like, I cannot separate these things anymore. I cannot only do art over the summer. I’m trying to retrain myself to not think of art as extra or on the side. When I was at the IPRC I was unemployed, so I had the space for the first time since I was 21 to ask, what do I really wanna be doing? So I found myself in Portland like a teenager again asking, how do I wanna live? What do I wanna prioritize? Maybe not a teenager, but maybe more like my twenties because I have a good position that’s grounded and that fits me, but there’s still a bunch of other stuff that is not in my job description that I need to be doing.

The pages of All My Dad’s Cars (2019) with the artists’ dad, Steve McKinney, the subject of the comic. At a gallery show in California at Toby’s Feed Barn. Photo courtesy of Kacy McKinney

Marissa: When I found myself at the IPRC, I was coming from the fine art department at Middlebury where I wasn’t finding any models and was feeling very out of place. At the IPRC I got to realize that printmaking wasn’t about the fine art world or making a single piece. At the IPRC it’s about hanging out with people, or making zines, or just being part of that intimate world. I didn’t have to fit into the fine art world.

Kacy: I’m realizing now that the IPRC was a window into the fine art world for me. I was able to be around that amazing group of people and in that kind of space and work on comics and I could start to believe that I could be in the fine art world. And comics were leading me to painting and drawing and I am sort of like, Wait, am I not doing comics anymore? Am I an illustrator now? Am I a painter now? And I think, for now I’m not really doing comics and I’m okay. Just a couple months ago I finished a giant drawing that is inspired in some ways by comics, like I’m using the same pens I would use, but it’s six feet by four feet and it’s a life size pelican. That is not comics. And that’s okay. So I’m having to sort of settle into the fact that comics are a big part of my life, but I am like, does this mean now that I could have access to this world of fine arts? Yeah. And I’m like, could I do both? You know? How would that look? I wonder for how many people the IPRC leads them into a space of belonging that then allows them to see what they’re capable of and not just in one area.

Marissa: It’s a multi-directional hub. That tracks for me, and it makes me be like, “Ugh, the IPRC is so great!” It doesn’t shoehorn anyone into one way of making art. It’s like, we have these resources and you can do what you want. And I think it’s funny because I talked about the IPRC making me feel accepted outside of the fine art world, but like now I’m in this MFA program.

Kacy: I know. Look at you.

Marissa: I’m like, What? But this program is just a little corner of the fine art world that actually is comfortable for me because this program is questioning what it means to be in a fine art world. And I think that’s what the IPRC also ingrained in me. It’s a place of people being radical within whatever space they’re in. And so now I’m in a fine art world where people are asking what it means to be trying to make art. And what does it mean to be an artist and what does it mean to show work in the world and what is an art project even?

Kacy: And that’s the part of it that inspires me, I’m super drawn to this program. Every student that I’ve had a connection with has been amazing. It’s so inspiring to me to think that you could do social science/art and that’s actually the dream. And I think maybe what I wanted all along was this ability to think critically and do social practice.

I think I wanna say one more thing about the IPRC, which is that because of IPRC, I got connected to Short Run Seattle and I got the Trailer Blaze Residency. And I was so nervous for that residency. I was like, “Will I fit in? What will people think?” But I ended up getting so comfortable there and then got this connection into this Seattle-based women, trans, and non-binary collective. I was invited into this space with these people who are all deeply caring and deeply welcoming and they told me, you belong here and your art is good enough and you are good enough and we need you. It still gives me chills. I realized that I’m looking for that kind of community. That’s why I’m drawn to the program that you’re in because it feels like it offers some of that. Some of the, we are critical, we are welcoming, we are warm, there’s space for all of us.

Trailer Blaze Residency 2019 Residents and Short Run Seattle Board Members (left to right, top to bottom): Lee Bess, Kelly Froh, Graciela Sarabia, Amy Camber, Alejandra Espino, E.T. Russian, Lori Damiano, Leela Corman, Kacy McKinney, Ashley Franklin, Eroyn Franklin, L. Armstrong, Jessica Hoffman, Megan Kelso

Marissa: In academia, especially, there’s such a push for being critical. I love the spaces that are like, you’re here, you belong, but also, what could you be doing? Is that really what you wanna be doing?

Kacy: Yeah, but that’s like a good friendship, right? You don’t want a friend who’s just like, No matter what you do, you’re wonderful. Everything you do is wonderful. You want the one who’s like, Wait, I just heard you use that word, like, are you sure you wanna use that word these days? We’re not really using that word anymore. And you’re like, Oh, shit. Thank you. Or the friend who’s like, I’ve noticed you’ve been interested in this thing. You haven’t really talked about it. Can you say more about that? I think that’s the right kind of belonging.

Marissa: Do you wanna talk about Changing the Narrative? And the ways it’s twisted together and pulled in these pieces of your life and your interests? How has that felt? What have you learned?

Kacy: Yeah, I love that you see that because it feels very natural to me. I have students who want to start right away and I like to express that this took all the things that I did before it. And I’m not young and I didn’t just start out, maybe I wish I could have done it sooner, but the only way that it has been successful is based on the relationships and the experiences I’ve had. Everything has been important: education, certainly the places that I’ve traveled to have been important, the languages that I’ve studied.

The biggest pieces are the pieces when I stepped a bit away from academia, and that was volunteering at Sisters, and I think we did it sort of the same way. I got interested and I got invited to volunteer right after I moved to Portland. And I was sold on day one. I just was like, this is hard and it’s wonderful. I met so many incredible people and started to make friendships. And then at the same time I did the IPRC program and it started to feel like I knew some of the key people and l was getting to know the richness of artists who exist in this area and what they’re capable of.

By that time, I was at PSU and starting to feel comfortable, and there was a grant application that came up that was from the Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative. And I thought, I can get that. It was the first time that I just was like, okay, like these things come together in my mind and it makes sense to me. I care deeply about students and their wellbeing, and I care deeply about homelessness and dignity and respect and stories, and I care deeply about comics and their ability to tell complex stories in ways that engage people deeply. And it feels right to both recognize that yes, I’m an artist, but like this is not about my art. Let me be a facilitator of this happening.

It was very exciting to think about being able to compensate students and hear their stories and value their stories in a deeply respectful way. It was exciting to think about being able to compensate artists and I knew there were so many that we would have to choose from. I knew we would be able to find 10 artists who cared deeply about the project and maybe had some lived experience.

I expected from the beginning that the stories would be really wide ranging and so, therefore the art needed to be very wide ranging. I put it out into the world and then when I got it, I was like, this makes sense that I got this. This is right.

Marissa: I’ve been thinking about comics artists as organizers, about the anthologies that people put together and the ways that you can be an artist that taps into these kinds of organizing and synthesizing skills, rather than just being the visual artist for a project.

Kacy: That’s so interesting, yes. That part of it is hard for me because people will say, what was your role in it? And I’m like, Ooh, the editor? Facilitator? Organizer? Researcher? Selector of people? There’s so many skills that I’ve developed in the process. I sort of did everything and nothing is kind of how I think about it. Right? I made the whole thing possible and they’re not my stories, it’s not my art, you know? I’m trying to understand true collaboration– collaboration in which you are that person, just like you’re saying.

Marissa: What are you thinking moving forward? Like what are the things that need to stay and what are the things that are more flexible within the project, for the future?

Kacy: I think I was just talking to students yesterday about the process, because I’m teaching a methods class and we were talking about how much you have to know in advance to be able to do it. Olivia’s working on a project with me called “Epilogue,” that is requesting the participation of all 10 artists, all 10 storytellers, the three interns on the project, and the two research assistants to come back and creatively reflect on what their experience was with the project. It’s less of what we should do differently next time and more of what did it mean for the artists and what did it mean for the participants? I think I’ll learn more about what to do differently next and how we can build and how can we do more? How can we work more with IPRC? How can we work more with Street Roots to make it easier for them, but also to engage vendors in meaningful ways?

And then I’m trying to raise funds to do the whole thing again. And I do think in this process of reflecting with the whole group of people, there will be some really concrete things that I find I wanna do differently. But the biggest and most important part is like finding the right team. And I’m hoping to do another one in two more years. I’ve doubted whether the right thing to do is to do the same thing again, but if the whole point of it is to share as many wide-ranging stories as possible that are unique and beautiful, then like we just need more. If it’s working, why would we stop? The social scientist in me is like, but what questions are you asking? And are you asking hard enough questions and are you building more data to inform the academy? I have to remind myself, that’s not what this is. This is creating more opportunities to tell stories and trying to change how people think about homelessness.

Marissa: Yeah, and the structure’s already there. There’s such a pressure to do something different, to ask different questions. But since we’re working with people it’s gonna be different and you’re gonna learn different things every time even if you use the same structure.

Kacy: And that’s the point, right? I’m always talking about Chimimanda Adiche’s idea of “the danger of a single story.” I’m always asking: are we telling one story about this really complex thing? Homelessness is a perfect example. We’re telling like one or maybe two stories that supposedly apply to everyone. And anyone who’s experienced housing instability knows that there are so many different reasons why this could happen. It’s so systemic, right? It is so based in discrimination and inequality and poverty. Can we stop selling the same story? Of course we need as many stories as we can have.

Marissa Perez (she/her) grew up in Portland, Oregon. She is a printmaker, party host, babysitter and youth worker. She’s interested in neighborhoods and the layers of relationships that can be hard to see. Her dad was a mail carrier for 30 years and her mom is a pharmacist.

Dr. Kacy McKinney (she/her) is a critical feminist geographer and Senior Instructor in the Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning, and Affiliated Faculty in Comics Studies. She is an artist working in comics, painting, illustration, and textile design. She is a graduate of the Certificate Program in Comics from the Independent Publishing Resource Center, and has had residencies with Short Run Seattle’s Trailer Blaze, Mesa Refuge, The Sou’wester, and The Verdancy Project. She has received grants from Regional Arts and Culture Council and Portland State University for her work in the arts and comics scholarship. She served on the Board of Directors of Sisters of the Road from 2018 to 2021. Her current research: Changing the Narrative Through Collaborative Comics is funded by PSU’s Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative and is in partnership with Street Roots and the Independent Publishing Resource Center. Courses of particular interests to art students that she teaches include: USP410/510: Arts and Community Change (Spring 2023), USP407/507 (and WR407/507): Comics into Research (Fall 2023), and USP325U: Community and the Built Environment (Fall 2023).

Is Everyone Having a Good Time?

Text by Becca Kauffman with Victor E. Viking, Portland State University mascot

“I could care less if we win or lose. I think the experience for me is more, is everyone having a good time?”

‘Z’ aka Victor E. Viking

on PSU campus next to my studio. Portland, Oregon. 2023.

What makes a good time good? I suspect that a hallmark of the “good time” is, quite often, a felt sense of togetherness. Yes, good times can be had alone, and yes, bad times certainly happen in the company of others, but it’s around people that we are reminded of our common humanity; physical proof we are not alone; a temporary dissolution of the hard lines we draw around ourselves. As Elias Canetti says in Crowds and Power, “Only together can men free themselves from the burdens of distance.” And that’s good, right?

It makes sense, then, that within the extraordinary scenario of being en masse (say, at a sports game), there would be an additional element (say, a mascot) to serve the purpose of emphasizing that good time. A mascot acknowledges our value as spectators and rewards us for our presence, amplifies our enthusiasm and reflects it back to us. In the chaos of whistleblowing umpires, aggravated coaches, injured players, fast talking commentators, fouls and buzzers and wins and losses, the mascot acts as a hospitable interlocutor to guide us through, reminding us to enjoy the hubbub, smile for the jumbotron, and accept a fist bump when offered.

I don’t know about you, but mascots are what keep me in the game, when I’m at a game (which I rarely am). There’s something about a seven foot tall, plush dolphin that hits different than a mortal human of flesh and blood. It helps that the mascot even physically scales up in size to proportionally support the crowd’s massive, collective spirit. That seven foot dolphin creates a larger than life fiction you might actually, for a moment, believe; a world where it’s safe to really care about something, to get on board, to root for some basketball team just because they play for your college, to embrace your regional pride or even some kind of newfound patriotism, if only for a couple hours.

Mascotry strikes me as performance art woven into a genre—sports—that we rarely associate with creative expression. And this is where it gets interesting for me. As a self-identified entertainer, I treasure the theatricality and clownish sensibility of these costumed cheerleaders. I relate to their keen consideration of the crowd (what’s a performance without spectators? We need them!) and their ability to distribute equal attention to the players and the audience like a cordial party host. A sports arena is effectively a theater in the round, where everyone watching the game also gets to watch each other. We are all implicated in the experience, and we all play a part. The lively group nature of a sports game recalls the participatory culture of ancient and Elizabethan theater, when it was customary for audience members to respond with loud utterances and a lobbing of stones or a goblet of wine. I love that mascots become a conduit for the collective buzz of the spectacle.

I recently started hosting a weekly public dance happening at Lloyd Center Mall in Portland called Public Acts of Dance Company, and realized that I am effectively a mascot for the “game” of dancing publicly at this half empty shopping mall. In front of the shuttered Hollister or the former Champs, I observe Saturday shoppers walk past us with perplexed or piqued looks on their faces, and I respond by smiling, dancing harder, and beckoning them to join us. I’ve coaxed a few passersby, but I have to wonder if my success rate would increase if I were dressed as a giant sneaker or an absurdly proportioned saxophone.

February 2023. Shuttered Hollister store, Lloyd Center Mall, Portland, OR. Image courtesy @deptofpublicdance.

February 2023. Lloyd Center Mall, Portland, OR. Image courtesy @deptofpublicdance.

Saxophone courtesy of aliexpress.com. Sneaker courtesy of redbrokoly.com.

For all the output of energy and attention toward the crowd’s experience, though, you have to wonder: where does that leave the mascot? What’s it like behind those eyes? For answers, I turned to the closest mascot within reach: Victor E. Viking, the official mascot of Portland State University (PSU).

Mascots aren’t allowed to speak, but the people who play them are. Inside the Athletic Pavilion on campus, it’s “a well known secret,” who the human being is underneath the plush covering of the PSU viking costume, but the identity of “Z” must remain anonymous to the general public. Z works in the marketing department, which is a nod to the fact that mascots are, in truth, a branding strategy. Plus, this position helps conceal his true affiliation with the sports department— only the tennis team, with whom he shares a locker room, and the cheerleading squad, who sometimes teach him a routine, are in on it. His second life will be revealed at graduation, where tradition will have him walk in Victor’s enormous, plush sandalled feet: “It’s supposed to be a final, Oh, this is who it was the whole time.”

PSU tennis team locker room, Portland, OR. February 2023. Photo by Becca Kauffman.

Until then, Z, who possesses the mascot’s holy trinity of athletic, theatrical, and hospitality experience, lives an anonymous dual existence as the one and only mascot of Portland State. As I learned from talking with him, that can be “a weirdly alone experience.” Maybe that’s what, in part, propels the presiding social nature of Victor’s personality. After all, shouldn’t everybody be having a good time?

Becca: How did you become Victor E. Viking? Did you have mascot experience? How long have you been doing it?

Z: I was an athlete, but I was also big into theater. I did a bunch of musicals in high school every spring when I wasn’t playing sports, and that was one of my big niche things that I really liked doing. So when I heard about the opening—which I found out about through a friend, they hadn’t had a Victor in two or three years because of COVID— I remember telling them at the office, Hey, I can just do my best and it’ll be a lot of learning on the job. I showed them some of my theater work, and it just lined up. This was last summer. So I’ve been on the job for six months now.

Becca: How did you train? Or audition?

Z: There was no audition. It was like, Put on the outfit. It fits. Let’s take you to a couple of games, let’s have someone come— they call it a handler— with you; make sure you’re comfortable, and then they’ll report back to us and we’ll get an idea of how you did. My first couple events, I was really worried about how I looked. I’d be like, Hey, does everything look normal? They were like, Yeah, dude, we’re just happy to have a mascot here, you’re overthinking it. So a lot of it for me was understanding that it’s really about just being there and being seen. You don’t have to go so hard and constantly do everything. A lot of it is tough, especially interacting with so many different people, and with limited vision. You can’t see very well at all.

Becca: Through those two eye holes?

Z: That’s it, that’s all you have. So a lot of it is just sort of winging it. I’m way more comfortable at home games because I know the Pavilion really well. It’s been a great season for me personally, because I’ve been able to grow into it and get more interactions with the players. It was a good confidence boost, I think.

Becca: What does growing look like? What’s your vision for where you want to be as the mascot?

Z: As a mascot, you’re like a mime. You can’t speak, but you need to display some sort of emotion. That for me was really hard. I may have done theater, but I’m not the most creative person. So a lot of it was like, Okay, I can do this, and people are responding well, so I’m always going to do this every time there’s a situation like that. I do a lot of repetitive action. You want to kind of stay reserved. One thing I do is I’ll taunt the other team when they’re shooting free throws. But you don’t want to go too far, because they’re college athletes too. Even if we’re playing them, I want them to do well, and I don’t want them to feel like it’s a mean thing. That’s just how Victor is.

Becca: That was a question of mine: who is Victor E. Viking?

Z: Uh, I don’t know. He’s way more confident than I am, I will say that. He’s definitely more cocky than I am. And he’s probably a little annoying. But I think those are all good traits for a mascot. When I put on the Victor outfit, if I see a player complain about a foul, I’ll start doing the crying [motion]. I guess he’s like a troll. A nice one. I always clap for the other team and go visit with the visiting fans.

Becca: So he’s slightly provocative to keep a competitive edge, but still supportive of everyone in the room.

Z: Yeah. I would rather be a bit more empathetic with my approach, versus, if we lose I still want the players to know they did awesome. I could care less if we win or lose. Most of the time I don’t even know the score because I’m walking around trying to shake hands and take pictures, rather than actually pay attention to the game. I mean, I think it’s important to win, but I think the experience for me at least is more like, is everyone having a good time? Did the families, did the kids, or the little brother, little sister, get to dap up the Viking? Because when I remember my experience with mascots, it was always a family thing.

Becca: What kind of value do you feel like the people that you interact with get from getting close to the mascot? Do you feel like they see you as some kind of celebrity? Is there a kind of larger than life excitement getting up close to Victor?

Z: There’s definitely different reactions. A lot of students are too cool for it. I’ll try to dap them up and they’ll kind of look at me and I have to just kind of get them to go. But then there’s other students who are just totally into it, absolutely love it. I try as best I can to give everybody attention, but those are usually the people I will float towards just because it’s easier to get that confidence. When the dance cam is going, you want to be dancing next to people instead of just dancing by yourself. Families are always very easy, because kids don’t care that nobody’s ever heard of Victor E. Viking. You float towards the people who are more into it.

Becca: You’re finding your audience.

Z: Even the game we had here last Saturday, I think most of the people were fans of the opposing team. I was waving at this one little section of the audience and this lady was not having it. She was just like, “Can you move?” She was just like, not about it. A part of me wants to stand there, and just wait as long as I can, act like I didn’t hear her. Another part of me is like, Well, I could just like go say hi to this family who, yeah, they’re all from the Eastern Washington team, but they’re all super into it. Maybe they give me a thumbs down, but they’re very nice about it. It’s very vibe oriented.

Becca: Do you think of yourself as an entertainer when you step into that space?

Z: It’s like pantomiming. You can’t speak, and I have always thought that the best thing about acting is being able to convey something without words. I think that’s the whole point of it.

Becca: The wildest thing about wearing a mask is that you can’t communicate through facial expression and instead you have to translate everything to your limbs and the way that you’re holding your body.

Z: Posture is a big thing, I realized.

Becca: Are you making facial expressions underneath that head, even though his face is out there, never moving?

Z: Absolutely. I’ve caught myself doing it a bunch of times. And I have to make sure I don’t make a noise. I don’t know about other mascots, but I definitely still hit all the facial expressions. I honestly think maybe that’s better for the performance because it’s more natural.

Becca: How does suiting up as Victor affect how you approach the rest of your life? Do you find that the attitude seeps out?

Z: It does for a couple hours. During football season, I went to the grocery store after a game and I felt like everyone was looking at me. And it’s like, No, they aren’t. It’s just because there were two hours of that straight. You have to catch yourself a little bit.

Becca: Totally. Sometimes there’s a real afterglow when you’ve been in the position of entertainer or someone in charge. Like you’re somehow carrying it on you. So maybe they really were looking at you, who knows?

Z: I wouldn’t be surprised, especially because you look kind of crazy after. I’m a pretty fair skinned person, and my face looks extremely red, and my hair is still a little sweaty. I’ve definitely, on my way out, had teenage kids say, Oh that’s the mascot! So I give them a thumbs up.

Becca: When your own humanity is obscured by this costume, does it ever get a little lonely?

Z: There are usually four to five mascots at a university, but because it’s a smaller program, I’m the only one. I’m friends with Benny the Beaver (of Oregon State University)– it’s my friend, Ryan. He tells me he hangs out with the other mascots like every day. So I think the only negative is that it can get a little lonely in that sense. My girlfriend will come to the games and my mom will sometimes come. The social media team I’m very close with, because I do a lot of work with them. But it is sort of a weirdly alone experience. You’re the only one feeling it and you’re the only one going through it. Especially if you don’t have the best interaction with somebody or maybe the night didn’t go as well as you hoped it would. I think that’s why I am not a big fan of the anonymous rule. I love that I’m close with the tennis team, because they know, and there’s a sense of trust there. It’s a little bit of a shame that the basketball team and football team aren’t supposed to know, because I feel like that would only bring us closer, right?

Becca: I relate to that loneliness as a performer. People can fall in love with that thing they see up there, but then at the end of the day, you’re you under there, and you haven’t necessarily been seen. Do you feel like being incognito at least gives you license to amplify some part of your own personal expression?

Z: Yes, it does. But you are also taking on a different persona, right? So the self expression, the creativity, that part of it is great, but there is also still a sense that, this is Victor, it’s not… It is me, right, and I’m the one controlling it. But I think the anonymity factor kind of makes it so… I don’t know.

Becca: It’s like you can’t quite take all the credit, because you’re not being perceived as yourself. You’re pulling the strings of the puppet.

Z: And there’s definitely a sense of freedom to that. I’m not the sort of person who would be in the center of the court, dancing. But when I have that on, who cares? No one sees that it’s me. That’s what they told me in the office about the anonymous rule. So I understand that part of it. But I think that people should be able to be that person, if they have it in them. Maybe the mask, the head, the costume isn’t always a good thing, in that sense. But if it ever got to the point where I was having a hard time with it, or it felt like something I needed to get off my chest, or something I talk to my girlfriend about when I get home, then I would mention it to them. But I don’t really care, it’s just the formal thing. It could be worse. I could not enjoy doing it.

Becca: It is interesting that one of the main purposes of the mascot is to bring everyone in the room together and represent this act of gathering, the athletic spirit and the excitement of a game and togetherness, all inside a culture of teams, and then here you are, the only one that’s not on a team.

Z: I think that’s more a product of us being a smaller program. Oregon State, there’s definitely more of a team aspect to it. But, you’re not totally alone— a lot of the cheerleaders I’m pretty close with; I go to their practices once a month or poke my head in if they have choreography for me to learn. There’s definitely still a sense of community, but it’s just probably less so than other programs. But that’s not a bad thing, right? Like, that’s also just a product of where you are and who you are, and the school you go to.

Becca: Has there been any talk of the team name and the character of a viking coming from an ancient, Nordic, plundering, settler culture?

Z: There hasn’t since I’ve been here, but I’m just a big fan of an animal mascot more than any human mascot. So like, I get it. I’m new to the Pacific Northwest, but I pretty much had the notion that a lot of people here have some sort of Nordic background. That’s a bit outdated, probably. I would hope that one day, they adopt an animal. I think that’s an easier thing to root for. It’s a little less creepy to have an animal mascot versus a spartan or a viking or a pirate. You know what I mean? A big thing for me is like, cuteness, right? If I see a mascot as a cute animal, I’m more prone to interact with it, versus that dude with the big muscles. I think that’s just a me thing, because I’m the one inside the costume. I don’t want to be creepy.

Becca: You’re like, I know how I look right now, so I’ll factor that into how I behave and interact with people.

Z: If you get kids who are really young, a lot of the time they might get a little creeped out or scared. You see that and you’re like, Man, if I was just a dog, or a bird, people would not feel that way. At least to me, it’s like, maybe don’t give him a golden beard. Give him like, a black beard or— especially because I’m a history major, and that’s a big thing for me is the historical value of it. There’s definitely a weird fascination with the entity of a Viking, where it’s like, you just go in and do whatever, and you’re more brutal than anyone else. No one can stand up to you. And I think that’s like a very American mindset. I’m not sure if that is cool. I think that there’s just a mythos to it that is very American in that sense, where it’s like, no one can tell me what to do. I’m stronger than you, even if I’m not smarter than you. It’s one that I personally do not relate to. I always, in my head, I’m like, Well, I hope I’m the only one thinking that.

Becca: You’re probably not, and I think that’s a good thing, that people be a bit more critical of it. I also wish that the mascot was a cute animal.

Orlando Magic’s Stuff the Magic Dragon courtesy of rocketsport.com.

Z: When I was a little kid, I was always a Dolphins fan. Their mascot was the cutest and the most out-there animal that’s in the league. It’s a dolphin wearing football pads. How could you not love that?

Becca: A dolphin with feet! That takes the fiction to another level.

What does it take to be a mascot?

Z: I think it takes being a proactive person, more than a reactive person. When I worked in hospitality, I always saw myself as going that extra step forward. I think that that’s why I do well in the mascot outfit. For example, I went to the Phillip Knight tournament this year, which has a lot of bigger schools like Purdue and Florida, West Virginia. The Florida mascot was a gator, and he was sitting down the entire time, and I was like, I don’t want to be that guy. Even if I’m not the gator, I’m just like this obscure mascot, I’m gonna twirl my arms around a little bit. I think it is having a sense of confidence that is also boosted a little bit by the fact you are anonymous and you’re wearing a costume.

Becca: How do you maintain a sense of optimism in adversity, inside of a game situation?

Z: I have the approach of, don’t give up and just keep going. If the clock is running, then you need to be going, going, going. And maybe part of that is just a sense of work ethic. Even if you’re getting beat real bad, you can act like you’re worried about it or you don’t like it, but you still have to be performing, you know what I mean? When I’m down there, and I can feel that nobody has a good vibe, nobody is reacting, I think that’s where the work ethic part of it clicks in, where I’m like, Well, it’s my job. Even if it’s not the only job I do, I’m gonna do it the best I can for the three hours I’m in this costume. No matter what the circumstances.

Becca: Imagine a team that had no mascot at all. How would that team suffer? What happens in the absence of Victor?

Z: I think you lose some of the ambiance. You lose the feeling of having that host. You can still have an awesome experience, but would that kid on his way out be saying, “Go Viks,” if he didn’t see the Viking there as a symbol of the team? I’m not sure. I do think you lose a symbolic value.

Becca: Do you have any mascot ambitions beyond PSU, now that you’ve gotten a taste?

Z: I’ve thought about it. Maybe a local sports team, or even if they needed somebody at the high school [I worked at] to wear the suit for a year, I would do it right away. But professionally, I don’t think so. I think there are people who are built better for it than I am. I’m 25. So it’s like, how long can I even do this for? It’s a tough job. I feel it the next day, a lot of the time. But I also wouldn’t rule it out. I enjoy being a performer, but I enjoy other aspects of my life more. I remember listening to interviews of professional mascots. A lot of these guys are in their 30s and their 40s, and they’ve been doing this for a long time. They dedicate their lives to it. Maybe if teaching didn’t work out, and I was like, I just want to be a mascot, maybe. But I enjoy being myself. I think anyone who works as a mascot for that long has to really enjoy being that character, at least on equal par with themselves. You know?

Becca: Have you felt different since you started embodying Victor? Do you feel like you’ve taken notes from Victor’s personality in any way or discovered a capacity for one of those traits that you weren’t aware of before?

Z: I think I became a better dancer, which is cool. When I take off the costume, I’m me, right? If anything, more of me has rubbed off on Victor.

Portland, OR. 2023. Photo by Becca Kauffman.

Becca Kauffman (they/them) is a socially inclined artist working in Queens, New York and Portland, Oregon. Practicing art as a public utility through interactive performance, devised gatherings, and neighborhood interventions, their work is currently situated at the local shopping mall and has also taken the form of an unsanctioned artist residency in Times Square, a public access television show, wearable conversation pieces, DJ sets, music videos, choreographed stage shows, original pop music under the moniker Jennifer Vanilla co-created with NYC producer and technologist Brian Abelson, a pedestrian parade with a group of fifth grade crossing guards, and a comprehensive artistic campaign to get a crosswalk painted in Queens. beccakauffman.net

Z (he/him) is a 25 year old originally from Virginia and now living in the Portland Metro area. He is pursuing a degree in history with the hopes of teaching his own students one day. He enjoys spending time with his dog and his girlfriend and doing various outdoors activities such as fishing, gardening, and hiking. For him, mascoting feels like a natural extension of his background in theater and something he does to connect with fellow students, athletes, and the school as a whole.

Can We Have a Dance Party Here?

Text by Diana Marcela Cuartas with Taravat Talepasand

Diana Marcela Cuartas with Taravat Talepasand

“Regardless of where you are, who you’re working for; if you’re working with yourself, or if you’re working with others. That’s the moment where a magic is happening. It’s about how we can talk about things so we can feel like we’re all sharing a safe space where we can speak freely without judgment.”

-Taravat Talepasand

I first met Taravat at the closing party of the Dream Girl exhibition by Sa’rah Melinda Sabino at One Grand Gallery, Portland, in October 2022. While dancing and sharing our excitement at how good the DJ was, I learned she was one of the new faculty at Portland State University School of Art. I started following her work and found myself delighted by its rebellious, vulnerable, and fun nature; a powerful combination very much needed in the academic landscape.

Later on, she had a solo show in Minnesota where, among works from the last 17 years of her artistic career, she presented a video of herself dancing on public TV at age 10. Even as a little girl outside the art-world context, a captivating playfulness was present in her performance, embodying the same inquiries as her adult-life artistic work, as a masterpiece created in advance for future questions. In the PSU Art and Social Practice classroom, we call that “retroactive claiming.” The term, coined by Harrell Fletcher, the program founder, references the possibility of revisiting the past to claim elements of it as artworks.

I reached out to Taravat, interested in hearing how she, as a studio practice artist, could relate to social practice terms. In the process, we ended up talking about the relationships between body expression, safe spaces, critical thinking, and how they arrive together on the dance floor.

Baba Karam dance by Taravat Talepasand. Still from the video. Image courtesy by the artist.

Diana Marcela Cuartas: I’m intrigued by a video you included in your current exhibit in Warsaw Gallery, where you appear dancing on public TV when you were a child. I would like to hear how you arrived at the idea of sharing it as an artwork.

Taravat Talepasand: That video of me dancing when I was ten years old on public access TV in Portland, at the time, was just embarrassing. I didn’t want to do it. I got coaxed by my mom, and she wanted me to do it because she wanted to show off to the Iranian community that I can dance. “Look at my daughter. She’s on TV!” It was definitely a place of narcissism and self-absorption, which is just part of Iranian culture—and other cultures can probably mirror that as well. But I knew at that time that it was something that was always going to be with me. I questioned myself, “What if people can see this any time, any day, at any moment that they want?” As if I knew this idea of the internet would be quickly unfolding in the future.

These videos came around 1990, and I found them on the internet around 2000. The Iranian station of that show uploaded all of their videos on their YouTube channel. It had like 60,000 views. Some people were like, “Isn’t this a weird dance? What is this?” But most people were like, “This is adorable,” or “Oh, she knows how to move.” For me, it was about realizing how I could turn something that I thought was kind of shameful into something that could be educational or informative, really grappling with a young Iranian American girl’s life in existence and identity. So I kept it; I knew there would be a time to share it.

Diana: Are you familiar with the term “retroactive claiming”?

Taravat: Retroactive claiming? I know what retroactive means, and I know what claiming is.

Diana: Harrell Fletcher wrote a book compiling his thoughts on terms and topics related to social practice. It includes retroactive claiming, which says: “An artist can retroactively claim elements of the past as artworks. That could apply to both object-based things—like photographs or a garden—and experiences—like going on a walk or having a discussion. To formalize retroactively claiming as an artwork, an artist can reframe it by giving the object or experience (or even a thought) a title, date, location, description, and potentially documentation […]”

Taravat: I like the retroactively claiming! I think that I do a lot of that in my art practice. That is a terminology that I can absolutely use to describe my practice, my way of thinking, and where I’m getting my inspiration. My ideas come mostly from personal experience or experiences that I’ve heard of, read about, or had been shared with me and given consent to work with, but those are all things that happened in the past. Reclaiming them now and making them into art, in a way, makes them almost a relic because things that we keep in our memory or our journals are personal. Most of the time we don’t share it, or they get forgotten or lost when we leave this world. But when you do work, publish something, or make it as an object, when you share it publicly, that becomes something else. And it also grows out of what is personal or what you thought was more isolating.

Diana: How did you decide to include the video in your latest show?

Taravat: I thought the exhibition at Law Warschaw gallery in Macalester College, Minnesota, was the right place to do it because it surveys a lot of my paintings, drawings, sculptures, and installations over the last 15-plus years. I needed something fun, a good grounding reset because you’re seeing all these works that you can see as beautifully painted or made, but the narrative is very political or can be controversial, a thread of female empowerment and conversation about the oppression of women in the Middle East. I needed something like when you buy perfumes, and they give you a bowl of coffee beans to reset your senses. The video is the reset for the exhibition. It was a place for people to see, “Oh, well, this is really just coming from this girl. This is her. She’s lived with this culture for a long time”. I thought this video would be a place for people to calm their senses, smile, or have that feeling you sometimes get when you see a child do something cute or playful. That’s what the video is for in that exhibition.

Diana: You seem so joyful and graceful in your dance, I wouldn’t tell your mother had to push you to do it. How was the preparation for it?

Taravat: There was a mixture of feelings when I was making that video. I was excited that people liked my dancing, and my mom was really proud. She was very, very excited for me, and as an Iranian girl, you get wound up into wanting to keep your parents happy. I understood at that age that assimilating into American culture was very hard for my parents as refugees. This was a place for them to be seen in a greater community and within the Iranian community that also existed in Portland. I did it more for her than for myself. I think this is one of the first moments I remember having a dissociative experience. I was like, “You don’t want to be here, but you’re here. Your mom is putting makeup on you; you’re wearing these ridiculous outfits; you’re going to dance to the music you’re so used to dancing to in private homes and parties. And now you’re very much in a public space.” So I left my body and danced my heart out the whole night, which turned into three videos.

I particularly like the one with the hat. It’s called Baba Karam. Baba means father, and Karam is a name given to a man. It’s supposed to be for men to dance only, but there are a lot of women that dance it too. I took on that challenge, and I knew in my body that there was some comfort in me wearing this non-feminized outfit; I wasn’t in a dress, I wasn’t in a skirt –I didn’t like those things as a child. It was the hat that really charged me. I was like, “Yes, I can play that part of a man or a boy,” knowing that I’m a girl and that my genetic makeup is feminine. That was the first moment that I got a challenge that stuck with me my entire life. My work is about these challenges, these roles that women are up to and are often told to play, and how we can erase those lines and boundaries as to what a woman should or should not look like, do or not do, say or not say.

Baba Karam dance by Taravat Talepasand. Stills from the video. Images courtesy by the artist.

Diana: I read you have an artwork installed at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Peace in the Middle East, that fell from the ceiling, and you were hired to repair it. In the article, you mention that, while fixing it, you wanted to reimagine your intentions about the installation more collaboratively. I would like to hear more about that. From the social practice perspective, there is this idea of studio practice work being isolated, not really in a dialogue with the community. Can you share how you worked to pursue a collaborative approach with that specific piece?

Taravat: That piece was part of the Bay Area Now in 2018 at YBCA. It’s a bunch of neon signs that say peace in Farsi. I had made these neons in a previous exhibition, and they wanted to have them in the show. They installed it with a very fine type of wiring, and what was supposed to only be there for a year ended up being there for three years. Something happened when there was a big windstorm, and they fell. YBCA was very unhappy about it because they had lived with this neon piece for so long, and they reached out asking how to get it back.

When I had to redesign this piece, the phrase that kept coming to my mind was, “You’re not alone in this. We can’t do this alone”. I wanted to seek a neon artist that was not necessarily Iranian or Middle Eastern but from a different community that could have a hand in this together. I picked the artist Ames at Rebel Neon in San Francisco, who goes by they/them and has fought for their human rights. It was important to me to have their hand bend this neon. Even though they say, “Oh, I’m just fabricating this,” to me, it is more “I sought you out. You are a part of this dialogue now”.

I reached out to several of my Iranian artist friends, designers, filmmakers, and people not necessarily in the fine art world to hear how they could see this reimagined. I also spoke to a lot of the museum’s employees and staff members who had daily contact with the piece to learn how people felt about that installation. I reached out to various gender, race, and socio economic positions, people that were included in the museum and people that were not, and I came up with this other version, very similar to the original it’s the same colors and neon; but positioned to drop down lower, so it can be seen as you’re walking up the stairs. It took a larger space that it needed to take up. It says Peace in the Middle East, but it also gives respect to the sacred geometry that is a part of the art history of the Middle East and Morocco and Egypt. It’s something that wants to encompass it all and doesn’t want to isolate whether you’re Muslim or not, or you’re Shia or Sunni.

Peace in the Middle East, 2017/2022, installation view, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, 2022. Photo courtesy Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. Photograph by Tommy Lau.

Diana: I was told since childhood that you shouldn’t talk about politics, but I like to imagine a world where you can talk about politics with your mom, your grandma, the neighbors, at the school, the museum… As an educator and first-generation immigrant, how do you cultivate the ground to start conversations to unveil taboos?

Taravat: My work is all about that. I’m pretty sure that students signing up for classes are smart enough to look up their professors. I would say 99% of the students that come into my classes know what they’re walking into. That the professor is a woman, a person of color, Iranian but also American, first generation, and can talk about this kind of displacement and constant negotiation of identity. And whether they can relate personally or not, students are intrigued and supportive of my work and know that they’re walking into these possible conversations in the classroom. So far, they enjoy the conversations that I am supporting.

One of the many things I tell students is that I’m trying to create a safe space here. I want everybody to be able to share how they feel honestly and openly. Whether that means they want to leave the space or if they want to say, “I think that there is enough about this conversation.” I love that challenge; I would love to be a safe person and a mediator.

We are constantly talking about what’s happening in the world, what’s happening in academia, what’s happening in the art world, and how we feel about it. I think it enables them to leave the classroom and have these conversations, go see work, attend a lecture, meet new people, and have an open mind. That is really the core of what I’m trying to promote.

Diana: What do you enjoy the most about teaching?

Taravat: I enjoy the kind of back-and-forth in the conversations that happen in the classroom. It can be ignited by the student or by me. When we start engaging and having a dialogue where we’re sharing our ideas, feelings, and research collectively, that’s the moment when it feels really good, that is very helpful in the real world, and I can feel that energy from the students as well. It doesn’t mean that they’re all smiling and in agreement. It’s that conversation; it’s that engagement; it’s “Share what you know about this topic” or “Share what you don’t know about it. What makes you feel enraged or uncomfortable? What can we really learn from this and take from it?”

Regardless of where you are, who you’re working for; if you’re working with yourself, or if you’re working with others. That’s the moment where a magic is happening. It’s about how we can talk about things so we can feel like we’re all sharing a safe space where we can speak freely without judgment. That’s the core of it for me. I learned that in college, and it did a lot for me, and I want to give that back to the students.

Diana: How can we harbor that kind of thinking and conversations outside art school? Because in a college-classroom context, we are somewhat safe, but in many communities outside the art world, a safe space for critical thinking is a privilege of difficult access and is not a priority.

Taravat: That’s interesting because you’re talking about the inclusivity of higher education, and that’s why I think KSMoCA is so rad. You are all getting in there at such an important time in these children’s lives and education to say, “Look at me. Look at what I’m doing. You can do this if it interests you. Let’s talk about it.” I never got that. My parents were like those parents “I don’t know about you being an artist. What kind of artist?” –Maybe an architect, maybe a graphic designer, you know.

As an educator, I think it is important to insert yourself to open conversations and invitations to younger classes and students. What I have learned here at PSU that I didn’t get from the previous institutions that I worked for is how important it is to be a part of a community outside the institution and be able to share who you are, your work, and how you teach in a very open way that can meet people that don’t have to pay the tuition to be at school. However, l know that that is still very narrow. But I’m always very much accepting those types of invitations. I’m seeking it, trying to be as open as possible.

Diana: The day that I met you, we were in this gallery, and we were amazed at how fun that was. It felt like a vortex to Portland in a parallel universe. Am I wrong?

Taravat: Yes. Sa’rah Sabino’s opening, where she had a DJ, hip hop music. It was like, DIVERSITY, all caps.

Diana: Why were you so surprised by that event having an out-of-this-Portland vibe?

Taravat: Okay, I was born and raised here. I can tell you firsthand the lack of diversity that the city and state have had forever. I mean, I have never been in one place with that many brown and black people in my life in Portland. So, I was so excited, it was really special and unique. I didn’t see that a lot, I hadn’t experienced that in Portland before. When I was a kid, I was the only brown person there; no one even cared where I was from; they just assumed that I was, you know…

Diana: Sort of Mexican?

Taravat: Yeah. And I was just like, “Okay, cool.” The thing is, in the 80s, you had to learn how to take it; today, nobody is taking it. We all are voicing our opinions, feelings, and preferences regarding how we want to be seen, right? When I was in my 20’s, going out to bars, clubs, and stuff, there was still a lack of diversity in those scenes. I remember around 2010, I was living in San Francisco and would come to Portland once a month, and I wanted to go to bars and clubs with hip-hop music, but It was so hard to find places that play that music here. There were all these articles that would put out something like “entices the wrong type of people.” So that opening was very special, one of a kind. Really exciting to meet you there as I was dancing.

Diana: What can we artists do to nurture that kind of Portland?

Taravat: I think that Sa’rah Sabino did it right. She created multiple events during her exhibition that generated many different communities to come together. She invited our undergrad students for a gallery talk. She had a couple of DJ open nights, and she just so happens to have a very diverse group of friends. I think that if we can have these kinds of events like just come and dance, just that alone. I mean.., do you know of any places where you can go and dance freely?

Diana: Only my living room.

Taravat: The pandemic really stopped that. There’s just a rad space in the huge lecture hall in the Shattuck Hall, the main floor. It’s just an open, huge auditorium, and I always think, “Can we have a dance party here? An Artist’s Ball?” I believe that the only way to break those barriers of inclusivity, and inviting communities to come together is to hold these types of events.

Diana: I couldn’t agree more.

Taravat Talepasand (she/they) is an artist, activist, and Portland State University art practice professor whose labor-intensive interdisciplinary painting practice questions normative cultural behaviors within contemporary power imbalances. As an Iranian-American woman, Talepasand explores the cultural taboos that reflect on gender and political authority. Her approach to figuration reflects the cross-pollination, or lack thereof, in our Western Society.

Diana Marcela Cuartas (she/her) is a Colombian artist, researcher, and curator transplanted to Portland in 2019. Her work incorporates visual research, popular culture analysis, and knowledge exchange processes, in publications, workshops, parties, or curatorial projects as a framework to investigate the relationships formed between a place and those who inhabit it. With her projects, Diana is interested in shaking off the rigidness of the systems we are inserted into by cultivating spaces to invite people to slow down, think together, share questions, and have fun.

Trash Talk

Text by Caryn Aasness with Dr. Christa McDermott

“None of my friends were surprised that I devoted my life to trash.”

Dr. Christa McDermott

A hodgepodge interest is my favorite kind. I feel my own work and interest is a hodgepodge of language, garbage, compulsion and how following them changes our relationships to objects and others, textiles, craft processes, sensationalizing, serving, and question asking, among other things. I get excited when I see people doing work that feels unprecedented in its specificity yet vital in its nicheness and connected to so many topics in previously unexamined ways. I get especially excited when the work touches on topics that compel me, but exists in the world of research and science, which feels so outside of my own realm. When I read Dr. Christa McDermott’s bio on PSU’s website that mentions the environment, women’s studies, and the “emotional relationships with possessions, how we construct identities through consumption, and hoarding,” I was enthralled and knew I wanted to talk to her. Our conversation was just as rich and varied as I had hoped and inspired me to think in new ways about trash, responsibility, community, and equity.

Evora, Portugal.

Caryn Aasness: To start, would you tell me a little about yourself and what it is that you do?

Dr. Christa McDermott: Sure, My name’s Christa. My background is in psychology and social psychology, my specific degree is Personality and Social Context, and I have a degree in women’s studies so I’ve always had this weird hodgepodge thing, because I’m interested in that and I apply it to recycling [laughs]. I went into psychology and women’s studies with my interest in environmental stewardship of objects and my own personal interest: I’m the person who pulls things out of the trash, have been since high school. None of my friends were surprised that I devoted my life to trash [laughs]. I take pictures of trash on vacation, I take pictures of people’s recycling bins. But I’ve always been interested in the people aspect of it, how we display our identities or understand ourselves through the things we own or want to buy, and the tie-in to capitalism and the fact that our economy runs on consumption and so, of course, we’re oriented to express our psychology through our stuff. I don’t think this is explored a lot in psychology outside of marketing and trying to sell people things. So I was particularly interested in terms of gender studies; consumption has always been tied more to women and women’s identity, like shopping, caring for things, and maintaining them is much more of women’s labor burden. Our relationships to things are also gendered. As a grad student, I made up a course that I taught called the Sex of Things. I’m just trying to lay out the relationship, the genderedness of our consumption.

Minneapolis-St. Paul Airport. “The ‘trash to energy’ label is deceptive marketing.

It is meant to make people feel better about throwing

out materials that will be incinerated.” Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota.

In graduate school you have more opportunity to explore what you want to do. At that time, the theories of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu were really influential to me and all of his ideas around different kinds of capital and social capital. And he’s got one book [Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste] where he did a survey of a bunch of different French people of different backgrounds about the kinds of things that they liked or had in their home. So, he’d ask, Do you like this painting? One painting is boats with rope on it, and another is ballerinas or different things. He did this with a very large sample of people and showed that people’s tastes are not as unique as they think, and they’re very much tied to their social class identities. Things that we feel are very much our own personal preferences are very socially constructed, and it’s not that we don’t have our own personal preferences, but I think we really underestimate how much they’re influenced by our social structures and things like our affinities towards other people who are like us, or our desire to make ourselves dissimilar to other people that we don’t want to be like.

But then, as I actually try to do work in this area, it’s not easy. All the things I’m talking about I rarely get to actually do. It depends on funding in the world, and much more prosaic things. So I’ve spent a lot of time doing energy efficiency work. Right now, the work I do at PSU is around recycling. It’s what other people are willing to work with you on or pay you for. I try to bring my lens, the social structure lens to that work, especially in recycling, people are obsessed about how to get people to sort things differently, and I’m like, that’s not the issue at hand.

Caryn: What is the issue at hand?

Christa: The issue at hand is getting people to use less, reuse more: how do you have social structures that enable people so it’s not just an individual thing? How do you have a society that helps people fix their things? How do you get companies to make things that are fixable? It’s less mechanical and more social. What gaps need to be filled in people’s lives? Right now, what if owning things and shopping and especially turnover of things is what is helping them feel better? Or holding on to things? I’m very interested in hoarding because I see so much good intention in hoarding, but it’s often good intention gone awry. From what we understand, hoarding disorder is mostly driven by anxiety, but there’s different levels of hoardingness, and in a lot of environmentalists, I see a lot of almost-hoarding. We’re all trying to salvage objects and maintain them. That’s something that doesn’t get discussed as much.

Caryn: You mention how lots of this work is tied to institutional support and funding: do you see people doing work that is effective or could be effective, but is outside of that institutional support?

Christa: Yeah. There’s lots of organizations working on these issues from different angles. I don’t exactly know that I’d say there’s one place where people have a more holistic view. What’s important is the coming together of all these stakeholders around different issues and making sure that you have a whole range of people represented: the activists and the nonprofits. Something that’s been really eye-opening for me is some work I started doing with canners, or waste pickers as they’re called everywhere else in the world. That’s a group that makes you think very differently about the structures around recycling and what it can offer people. I met Taylor Cass-Talbot with WIEGO, [Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing], a global organizing group of women’s informal laborers. She works with waste pickers all around the world and also helped start up a co-op here called Ground Score, a cooperative of canners advocating for their needs. At first, when I thought about canning, I was like, Well, that’s something we just have to phase out, this sounds like a terrible life, people picking through people’s trash, hauling things all around, why are you not just trying to end this? And she’s like, No, this is empowering. This is low barrier, flexible work. People build a community around it, and do you want to know who’s actually making sure most of your recycling is working? It’s the people who are coming through and pulling out the recyclables. And I had a 180. It totally changed my perspective, these folks are crucial to the system of recycling, and yet the system is literally designed to either not include them or to be actively against them. For example, the BottleDrop system [the system in which individuals can redeem recyclable bottles and cans for the refund value, often at grocery stores or dedicated recycling centers] was not designed for them at all. It’s not designed for people with hundreds of cans. There’s actually a limit on what you can bring in and grocery stores don’t want to deal with them. Canners experience a lot of stigma and prejudice. So they mobilized something called the People’s Depot where canners can drop off large quantities– it’s run by canners so they also aren’t experiencing discrimination and stigma and being hassled and looked down upon. It’s been eye opening to see the community around it and that social structure aspect of people being able to support each other. I find waste picking to be a really rich place for thinking about how we handle materials. These are people who know how to fix a lot of things or want things to be more fixable. They pick up all different materials for resale. People are finding ways to get by in a way that fits them better than the typical system even though maybe Waste Management isn’t going to hire them to drive a truck.

of trash from around the world. Madras, Oregon. 2017.

Caryn: What do you think is the best way for an individual to get involved or make an impact?

Christa: I’m a big believer in advocating for structural change. A lot of folks are very passionate about zero waste, and it’s individual behavior based, right? Which I mean, I engage in a lot of that as well. I’m constantly sorting all my special recycling, all my little caps, even though I know deep down that this is not really helping. But I also work on these other things at a larger structural level. So if someone has this interest, I say engage in structural advocacy.

I’ll give one example of how I found my way into this. After graduate school, I moved to California, back to Berkeley. There was this group there that combined meditation and environmental activism all around waste [Green Sangha], they were really great. We met about once a month, there was meditation and then a talk about plastic pollution, for example, and what we can do about it. We did some activism, writing old school letters. There was a guy who was like a little Al Gore, going around showing a PowerPoint. Because it was mindfulness based, they weren’t as interested in just looking at why all these things are bad. The PowerPoint had a section that was like, here are all the reasons why we all love plastic or why plastic is great in our lives, this is what it represents and does for us. But we also recognize that it has all these different problems. So it was very much open problem solving. What can we all do to reduce these impacts in our lives? Mostly, we need corporations to change their practices or to lobby legislature to make a different policy. So I’d look for those kinds of groups. I find them to be the most helpful.

of trash from around the world. Oregon.

Caryn: The group you run on campus is doing things that students can get involved in, right? Can you talk a little more about that work?

Christa: Yes, I run CES, Community Environmental Services, at Portland State. It’s different from the SSC, the Student Sustainability Center. We are entirely off-campus oriented. So all my staff are students— not everyone has a huge passion for trash but I’d say 90% of them do. We do a lot of technical assistance for local projects. Right now one of our big projects is for Metro Regional Government. They are replacing the decals on cans in multifamily housing and providing signs to update multifamily enclosures with clear signage. The reason why Metro is investing so much in this is because multifamily housing has had inadequate recycling and trash services— it is an equity issue. The whole reason CES got started was actually out of a student project around improving recycling in multifamily housing, because the recycling of multifamily housing has always been lower than in single family housing and the rhetoric around it is that those people don’t care. It’s impossible to reach out to people in apartments, it’s just easier for them to throw everything out, blah blah blah. And we’ve shown for more than 30 years that actually all the services and the structures in multifamily housing are inadequate and they’re not on par with those in single family housing where you have your own little cart, a weekly service, a newsletter from the city, if you live in Portland. It’s just so much harder in multifamily housing to access that. So Metro is invested, I feel like they’ve really stepped up their efforts. So even though we are putting decals on trash cans, it actually has an equity component. It’s meant to be a step towards making services equitable for all residents, whether you live in your own single family property or an apartment. So we do that kind of work and other kinds of work.

collection of trash from around the world. Hawaii.

Caryn: That’s interesting. How would you say the public perception of environmental issues and the role of waste has changed in the time you have been doing this work?