Uncategorized

The Tapes, Conversation I

“…There was that fear: What if I don’t have full parental rights, just because I’m not the biological mother?’”

MARTI CLEMMONS

Public Domain image by Renee Comet acquired from National Cancer Institute.

Tomatoes, with little tomato seeds, and tomato flesh dripping with tomato juice. Growing up, my grandmother and my mother were always exchanging tomatoes. Tomatoes that they either grew, or found at local farmer’s markets. They would give these tomatoes to family members, friends, co-workers, and each other. Although, the conversation you’re about to read has nothing to do with tomatoes. The conversation you’re about to read has everything to do with closed objects, restricted audio tapes(1), lesbian mothers, and custody trials during the 1980s. In the 1980s, my grandmother left her second husband to live alone in her own home, after her children had grown. In the 1980s, my mother graduated from high school, studied medical assisting and married my father. She also gave birth to my brother and then to me. My mother would later divorce my father in the 1990s, the same time she began working nights for the United States Postal Service.

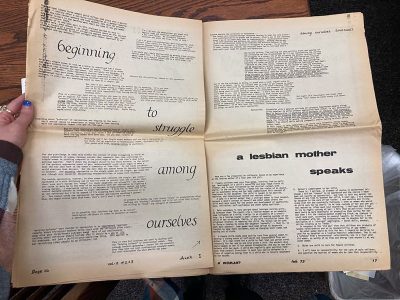

About a month ago, Marti Clemmons [an archivist, now friend and collaborator, who I met through my research assistant position with Portland State University’s Art and Social Practice Archive] shared with me a collection of restricted audio tapes. I wasn’t able to listen to them, but I was able to look at them in a box. These audio tapes were given to Portland State University’s archive from the feminist bookstore, In Other Words, after it closed a few years ago.(2) The tapes contained personal accounts of lesbian mothers in the midst of custody trials during the early 1980s. Their husbands or ex-husbands didn’t want the women to have custody of their children because of their sexual orientation.

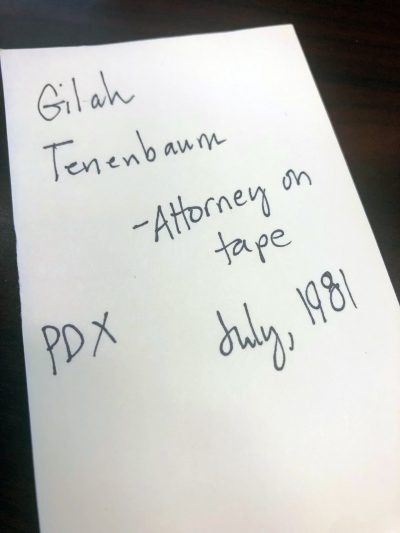

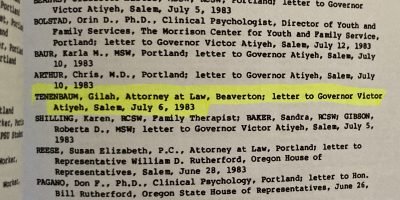

Having history as a single mom, who has had my own experience with lawyers, guardian ad litems, counselors, and such, I’ve developed a personal interest in post-separation abuse, coupled with the use of family court as a tool for abuse. Marti, being a queer single parent, has their own immense connection to the tapes. I told Marti that I would do whatever I could to help find the women on these tapes— to ask for permission to share their stories. We ended up locating a Gilah Tenenbaum. Gilah is a retired lawyer who was recorded on one of the tapes. Gilah doesn’t have children, but was active during the time of these trials and very much a part of the lesbian community in Multnomah County, Oregon. I reached out to Gilah and asked if she knew anything about the audio tapes. Maybe she could help Marti and I locate the people on the tapes so that we could get their permission to share these recorded stories. Marti had digitized the audio tape that Gilah was on.(3) We planned to meet with Gilah over Zoom while Marti was at the university’s archives so we could have her listen to the recording. Unfortunately, at the time of the meeting— as it goes with the life of parents— Marti was stuck at home caring for a sick child, so we weren’t able to listen to the recording. The closedness of the tapes, the remaining lack of access to the actual content of the tapes, adds more power to them.(4) And, consequently, for me, added more meaning to our dialogue about them. My hope is to document a succession of conversations in relation to these tapes from In Other Words, as we move through the process of searching for the people who are recorded on them. The following is the conversation of our first meeting, between the three of us: (Marti, Gilah, and myself).

Rebecca Copper: Marti, if you don’t mind going over some of the things you do and maybe give some context for these tapes, that might be a good introduction.

Marti Clemmons: Yeah, I work in the Special Collections and University Archives at Portland State University. I’ve been there for nearly 12 years, off and on. Now, full-time as an Archives Technician. I process a lot of the collections: I look through things, I throw away the things that don’t have significant historical context. I get collections ready for the researcher, or the user— patrons, students. We acquired a collection a few years ago from In Other Words, a feminist bookstore and collective. They were located in Northeast Portland. I think it was about five boxes. One of these boxes, it was offset, was a collection of about 70 cassette tapes. The custody tapes were of mothers who came out in ‘81— well, probably came out before that, but a lot of the tapes are labeled from 1981, 1982, and 1983— mothers that came out to their husbands, and therefore, their husbands took them to court for custody of their children. So, lesbian custody tapes, I guess is a broader way to describe them. I’ve only been able to listen to a few of them, they aren’t digitized. The only information on the tapes is a name and a date, sometimes initials. There’s no release forms. There’s nothing else.

Gilah Tenenbaum: Is there a name of an interviewer or an interviewee?

Marti: Usually, it’s just the interviewee. A lot of the time on the cassette tape, it might just have initials. I’ve noticed a few that have the same initials. Some of these tapes also take place in Los Angeles. I don’t know what that connection is, either. In an oral tradition or practice, the interviewer would state their name, who they’re interviewing, place, date and so on. I haven’t been able to listen to all these tapes, so some might say the names as they’re introducing. I know on your recording, specifically, it gets cut off, the interviewer’s name gets cut off.

I don’t think Rebecca told you yet— I think I recognize the other voice, the interviewer, which is even stranger. I took an oral history capstone class, from a person named Pat Young, who is a historian in Portland [Oregon]. I swear it’s her voice, but I haven’t made that confirmation. She has a very specific laugh, and it would make sense that she would be doing these tapes. I know that she did have some connection with, I think, Katharine Williams, who’s also mentioned on the tape.

Rebecca: Gilah, there is a Katharine that you mentioned. You said I should reach out to Katharine English. Is that right?

Gilah: She was one of the first, if not the first attorney, to win a lesbian custody case in Multnomah County. She educated the judges, she really put in a lot of effort. It came to be that you could go to court in Multnomah County, and you weren’t going to lose just because you were a lesbian. This was a long time ago, but I think the circuit court generally, in Multnomah County, not just this one judge, came around to deal with these cases the same way, whether or not they personally approved.

Marti: I’ve listened to bits and pieces of your interview and I’m sorry that I’m not at work, I had planned to share a snippet with you— but, you do mention different judges, and just the way that it works. How you would walk in, almost having to expect to lose. I feel like these women, you know, with every inch of their being, they wanted to fight for the custody of their kids. Going into court, it’s traumatizing and scary. And, on this recording, you had a lot to say about that and the different judges, not necessarily by name, but what to expect.

Rebecca: Marti is at home with a sick child. That’s why we can’t share the tape you’re on, we totally planned to have audio for you to hear.

Gilah: I was looking forward to it.

Rebecca: It’ll happen, though. I’m sure we’ll get it to happen at some point.

Marti: The recording is about an hour and fifteen minutes, it’s a long conversation. The snippets of the other tapes that I’ve listened to, it’s devastating. It’s their life stories and what they’re trying to accomplish while going through court. It’s really nice to have your tape. Not as someone who is going through a custody battle, but someone who has a different, outside perspective. I think you say on the tape that you were also community support during this time, so it was affecting you as well.

Rebecca: Gilah, you were just talking about how you weren’t sure how much insight you’d be able to give, considering that you weren’t a mom going through one of these cases. But you were a lawyer, you were a lesbian, and part of the communty. Because I’ve been through court custody-processes myself, when Marti showed me these tapes I was interested in the conversation about family court used as a form of abuse or control. So, there’s that way that I connect to the tapes. I wasn’t born until 1989. I wasn’t even alive when these tapes were recorded. But, you were the name Marti had. Then, I tracked you down. And you were there, you were physically there. To me, it’s valuable how the three of us are connected to these tapes. Also, how some of what was happening in 1981, is essentially, in some ways, still happening today.

Gilah: Oh, yeah.

Rebecca: I was hoping that maybe we could connect in a dialogue over that and maybe some of your experiences. I don’t have any prepared questions.

Gilah: I’m happy to help in any way I can, given all the caveats, you know. I have a vague memory– really vague. Maybe I even created the memory once we started talking; that I was once involved in something with interviews, but you know, I don’t remember a whole lot.

Rebecca: What do you remember?

Gilah: Just that it happened. Not any specific incident. I’m trying to think if I was in a conversation with Pat Young. Was she in a position of having to go through this? Or, were she and I talking as people who were providing support?

Marti: She was in the position… I’m going to pull up my email… Actually I think it is Katharine English, not Williams, now that I’m thinking about it. Let me just pull this up really quick. There are records that say that Pat was working with and doing this type of oral history interviews during that time.

Gilah: And she spoke about Katharine English?

Marti: I’m going to pull my email up, really quick. I remember asking Pat about this a couple years ago. She didn’t say whether she remembers or not, she deferred the question. I am trying to pull that email, I have to scroll because it was a couple of years ago. [laughter]

Gilah: While you’re doing that, Rebecca, how did you find me? It shouldn’t have been hard.

Rebecca: Um, yeah, no. It took me maybe a few hours on the internet. I learned, weirdly, quite a bit by googling your name. Actually, I forgot about this really cool thing I wanted to share with you. I got this booklet titled, Divorce. I printed it out through Google Books, which I didn’t know you could do, but it’s a collection of court documents and articles on divorce and its impact on children. There was a committee held in Washington, DC by the House of Representatives on June 19th, 1986.

Gilah: Is it a collection of essays?

Rebecca: It’s like court documents. But, your name is in this, you submitted a letter to a representative opposing joint custody. I have it highlighted somewhere. It was wild to find this and then be able to print it in a book; to learn there was a committee the House of Representatives created to discuss this topic in Washington D.C in 1986. As I was searching for you, I found that. I was led to your contact information through the Women’s Lawyer Group of Oregon. They connected me to the Oregon State Bar who gave me your email and your telephone number.

Marti: Nice.

Gilah: I tried to look up Katharine English through the Oregon State Bar. I didn’t know if there was a section for retired or inactive members. I resigned from the bar after I had been retired for I don’t know, three or four years— it just didn’t really make any sense to keep paying that money and I wasn’t practicing. I thought maybe I could find Katharine for you through them. But, I wasn’t able to. I don’t remember if Cindy Barrett was involved, but she’s an attorney. She’s now inactive. She certainly would have known what was going on and might have been involved at the time.

Marti: There was a Cindy in this email I’m looking for, Cindy Comfer.(5)

Gilah: Oh, Cindy Comfer! Oh, sure! I haven’t seen her in years. Yeah, Cindy probably worked on cases, maybe even with Katharine.

Marti: I found the email. Pat said, “I will forward your email to Cindy Comfer, who was a lawyer, retired now and did many custody cases along with Katharine English.”

Gilah: So, my memory is reasonably still there! [laughter]

Marti: Cindy wrote me back. This is from 2019. “I’m sorry, but I don’t know anything about these tapes. I remember Joanna from In Other Words. I did some lesbian custody work in the latter 1970s in the 1980s. But, I don’t know anything about these tapes.”

Gilah: Joanna? Did she give a last name?

Marti: Brenner? Yeah, she’s the one that started In Other Words and was active as a professor. I think she may have even started the Women Gender Sexuality Studies Department at Portland State [University]. But, that was the last time I looked into this. I was like, “Okay, you don’t remember.” And, I had so many other things to do in the archives. I got really excited… but…

Gilah: It’s possible that she knows how to contact Katharine English. She might be one of the last people that has kept up with Katharine. All I remember is that Katharine moved back to Utah. She was from Utah, originally. I think she was from a Mormon family. I don’t think she had anything to do with them. I don’t think they accepted her.

Rebecca: What was it like in the ‘80s, as a witness to lesbian mothers going through custody battles? I mean, would you be willing to share what that was like? No pressure by any means.

Gilah: I have a few memories I can share, not tied to specific women. These cases didn’t always come up in the context of a divorce. For example, I remember that there were women who specifically did not live with their partners, to try and keep it from the ex-husband. I remember there was a case one time where the woman got custody, but a condition was that her lover couldn’t live with her and wasn’t really allowed contact with her children. I don’t know if it was in the early 80s or the late 70s, I graduated law school in ’78. I remember that we heard stories all the time about women around the country who were losing their children, so we sent money. Those of us that could help pay for lawyers. It was just crazy. You know, just misogynist, homophobia.

Marti: Did you have that same experience, Rebecca? Well, I mean, you don’t have to go into detail. Did you deal with a lot of misogyny in court?

Rebecca: (6)

Gilah: I would highly recommend that documentary that I told you about, Nuclear Family. It shows a lot of what went on. I remembered when I was watching it, that the women couldn’t be married at the time. It was before there was any legalized gay marriage. That the non-biological mother was not allowed to have anything to do with these discussions. She couldn’t even go into the courtroom. She couldn’t be there for support for her partner. She was just left out as if she didn’t count, which is the same thing that often happened and probably still does. Like, when somebody dies, and their “blood” family comes along and says, “Well, I don’t care if you lived with them for 25 years…” and just completely excludes the partner from any kind of closure rights, whether property or whatever.

Marti: Yeah, when my eldest was born, she’s seven now, there was that fear, What if I don’t have full parental rights, just because I’m not the biological mother? Times are different [now]. Hearing this is just like— that could have been me, 20 years, 40 years ago. I ended up adopting my kids. That’s how I have full parental rights. There are ways around it now.

Rebecca: Even though federally, gay marriage is legalized, there’s still a lot of shit– excuse my language– happening in terms of rights. I’m thinking about conservative states and how much bias can play into a judge ruling.

Gilah: There was at least one time that I remember where a woman moved from somewhere else in Oregon, to Multnomah County. So, when things went to court, it would be in Multnomah County because things were clearly better here.

Marti: I mean, I’m sure that there were cases like that, with people moving elsewhere to get a fair trial, or something close to a fair trial. Yeah, you mentioned [in the recording] that people actually did do that. Wow.

Rebecca: Yeah, that’s a lot. I’m in Ohio, currently, because I can’t pick up my kid and move without money to pay for a lawyer, court fees, etc. And, even then it’s not guaranteed that the judge would rule in my favor. I would have to go through the process; start a motion to move elsewhere and prove that it would be in my son’s best interest. With moving elsewhere to get a fair trial, to even do that is difficult in and of itself. Which makes me think of mutual aid and support. It seems that there is a resurgence in that kind of community-based support.

Gilah: Just from the little that I’ve seen, it is coming back, the sense of a lesbian community is coming back around. Things have changed so much with the greater acceptance of people being gay or trans, however they identify. It’s on people’s minds more than it was in the past. I mean, with the whole craziness that’s going on with abortion, there are national, regional, and local groups that are raising money to help women pay for abortions. I don’t know if there was anything like that back then. I remember giving money, but the money was just funneled through the woman or through her attorney. I don’t remember there being any, or I didn’t know of [any]organizations that were specifically for that purpose.

Something I mentioned in our last email exchange is the Community Law Project. I’ve been trying to remember where it is, this yellowing copy of a 50 page book that was titled something like, Know Your Rights. It had chapters written by different attorneys, and I wrote something in it. [Laughter] I don’t remember what, but I know I have it. I saw it when I was cleaning out some stuff not long ago. There might be something of interest to you there. So I will keep looking for it.

Rebecca: Oh, cool! Thank you! Did the bookstore, In Other Words, close down recently? Like a couple years ago?

Gilah: Yeah. 2018, maybe ‘19?

Rebecca: Do either of you know why it closed down? Was it financial?

Gilah: I remember there being fundraisers more than once, to help keep it going. I think it was just not enough financial support from the community. I was trying to remember where the store was before it was on Killingsworth.

Marti: I think it was on Hawthorne?

Gilah: I didn’t go in there a lot when it was on Killingsworth [Avenue]. I did once in a while. I donated books to them and money; it was also a meeting space, and a safe space for people. I think [the reason] was just basically money, though.

Rebecca: Would you mind telling me a little more about In Other Words? I’ve actually never been there.

Marti: Yeah, it was in the Hawthorne District, originally. I only went into the Killingsworth location. It was small, you walk in, there’s a huge open area, like a gathering spot, lots of readings, lots of music, a lending library. It just felt like a safe space. I moved here from New York, where I went to Bluestockings Bookstore. It was nice to have the same type of vibe, energy and events to get connected, having moved here to Portland and not knowing anyone in the queer community, and going there and just being one with my people. I would always go there because there was a little music venue next door. If you didn’t like the band that was playing, you would just go to In Other Words and hang out. Yeah, I think it was just about the vibe and having a space that felt good.

Gilah: There was a place— I moved here in ’75, for the gay community— it was Mountain Moving Cafe. It was a cafe open for all, but it was known especially as a safe space for gays and lesbians. That closed and that was a real loss.

Marti: Yeah, I’ve come across that name many times in multiple archives. It’s like one of those places, where you think, Ahh, why can’t I time travel? That place just seemed so cool.

Gilah: It was.

Marti: There’s also the aspect with Portlandia, the show that filmed in In Other Words. I know that started off as a good connection, but it ruptured as they kept filming. There with little to no monetary support. And [the show] kind of made fun of, you know, us in the community. That left a bad taste.

Rebecca: Gilah, I was wondering about your position as a lawyer in all of it. With your expertise as a lawyer, in a courtroom, watching as women went through such a process, and understanding the biases of the judges. I’m curious, was there anything that stood out as unconstitutional, or unlawful, for example, that you saw or that you can remember?

Gilah: I don’t remember there being anything unconstitutional. I think there was a lot of white male privilege, assumptions and ignorance about anything to do with gender or sexuality issues.

Rebecca: What would be their [the judges and opposing lawyers’] reason to prevent a gay woman from having custody of her children?

Gilah: Well, that homosexuality was a sin, and illegal in some contexts. They didn’t want the children to be influenced by this. Also that children need a mother and a father. If the children saw two women being affectionate or holding hands, it was not good for the children. The standard is always, What is in the best interest of the children? Under that rubric, lawyers can argue whatever they want, and as you pointed out earlier, they would tear women apart. “Did you have a shoplifting conviction when you were 16?” I mean, so, what?! They would pull out anything they could. “How many times have you moved in the last five years?” Or, whatever, really. I can’t say there was anything really “unconstitutional” other than white male interpretation of the Constitution. You know, all “men” are created equal.

I did some domestic relations. Most of the cases that I handled were settled out of court. And, I did some writing on the way you protected yourself, as a gay person— as a gay person with a partner, or without a partner for that matter, In those days you had to have lots of documents. You had contracts between you and your partner about what would happen if one of you died. Because you couldn’t be married, you couldn’t get any of those assumptions or benefits. I helped people come up with living-together agreements. Like, wills and other contracts or documents to protect their rights, vis-a-vis each other: What’s going to happen if we break up? I was the one that had the money for the down payment. Yeah, but I was the one that was bringing in the monthly income. My theory was always, yes, it’s unpleasant to put one of these agreements together, but it’s going to force you to confront your issues, and to resolve them while you’re still totally in love with each other. That’s the kind of legal stuff that I was mostly doing during that time.

Rebecca: (7)

Gilah: I think I just remembered a judge’s name that Katherine worked on. I think it was Harlow, H-A-R-L-O-W, Lennon, L-E-N-N-O N. I’m going to double check that on my computer to see if he’s who I’m remembering. I would hate to be giving you the totally wrong name just because I happen to remember one of the judges.

Marti: Yeah, I really appreciate that. I feel like I remember you saying that name in the recording. I want to do this again, when I’m at my desk. I really do. I need to figure out if it’s Pat Young, first of all. Then, go forward with that. I don’t want to play something that no one has given permission to play.

Rebecca: Gilah, originally I was thinking we could give you a list of names to see if you recognized anyone, but we can’t actually provide a list. The archive can’t even give out names without signed release forms. Is there a way to work backwards? Like, if you think anyone you know could be on the tapes, could we check that name against the list from the tapes?

Marti: Unfortunately, that’s where we’re at, that’s the only way. [laughter]

Rebecca: I know you said you might recognize some of the names, if you saw them?

Gilah: Yeah. Oh, I might well recognize a name, but that’s not the same as coming up with it on my own. [laughter]

Marti: No pressure! [laughter]

Rebecca: [laughter]

Gilah: Offhand, I can’t think of any friends or even acquaintances who went through that. I think Katharine English had. Other than her, nobody comes to mind. It’s interesting. Katharine, physically, is a very small woman. I don’t think she’s more than five feet tall, but she’s feisty as the day is long. Articulate, and so on. I’m sure she had things to fight just because she was small in stature. It’s hard enough to get taken seriously as a woman.

Rebecca: Yeah, and I really appreciate that name, Katharine English. I’ll make sure to work with Marti, to see if we can locate her.

Marti: Yeah, and Cindy Comfer. I have a connection with that, too. I’ll shoot Pat and Cindy an email.

Rebecca: It’s 7:32pm [EST]. I know, Marti, you have to go?

Marti: Yeah, to pick up the other kid.

Rebecca: I hope Ansel feels better.

Marti: You know how it goes. [laughter] Gilah, it was nice to meet you.

Gilah: Likewise.

Marti: Let’s chat again soon.

Footnotes:

(1) The audio tapes are restricted because there are no signed consent or release forms on record.

(2) In Other Words was a Portland Oregon feminist community center and bookstore and was featured in several episodes of the Netflix comedy series, Portlandia.

(3) Due to the age of the tapes, they are digitized to prevent further wear and tear on the tapes from being listened to repeatedly.

(4) In a conversation with artist Lucia Monge, Lucia pointed out the power of a closed object.

(5) Mentioned in an email from Pat Young to Marti Clemmons as someone who may be connected with the tapes

(6) Redacted text

(7) Redacted text

Rebecca Copper (she/her) is currently a graduate candidate at Portland State University, through the Art + Social Practice MFA Program, where she worked in 2020 as a research assistant for Portland State University’s Art + Social Practice Archive. Rebecca’s work centers on ontology; how our being and perceptions of reality exist against one another. And, how that reality is mediated, dictated back to us in varying forms. She is deeply invested in vast inversion of imperial/masculine archetypes, power dynamics, and ideologies. And, the reduction of hyper categorical, industrialized research.

Marti Clemmons (they/them) is an Archives Technician at Portland State University’s Special Collections and University Archives located in the Millar Library and previously worked as the Archivist for KBOO Radio. They are interested in using archives as a place for Queer activism.

Gilah Tenenbaum (she/her) was born and raised near Boston. B.A. Government and Political Science, Boston University, 1970; J.D. Northwestern School of Law of Lewis and Clark College, Member Cornelius Honor Society and recipient of the first World Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Progress of Women’s Rights Through Law, 1978. Admitted to Oregon State Bar 1978.

I Went Back in Time and Everybody Else Was Moving Forward

“That’s what you learn from interfacing with other people. […] You kind of cling to each other after a while because not everybody out there enjoys what you do. So when you do, you find a kindred spirit. Boy, it’s something a little bit special.”

PERRY HUNTOON

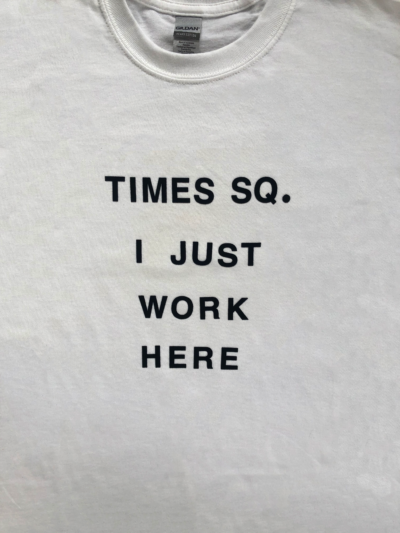

Social Practice creates a unique/nagging/obligatory need/opportunity/desire to investigate/create/document the places where people are making connections. Recently for me, this has melded with my interest in vintage aesthetics, pre-internet mediation, and self-initiated institutions. Zooming out from this mess of ideas and influences, I started to see a shape forming, and that shape was of a fan club. It’s the perfect intersection of ephemera, human interaction, rules and devotion. I started to research fan clubs that had been around a long time, long enough to still have a bit of a pre-internet history, and was pleased to find that the Guiness Book of World Records’ longest running fan club was The International Club Crosby. The club was started by fans of Bing Crosby in 1936 and is still around today.

I was enamored by their website and particularly struck by the availability of the leadership’s contact information. There were people seemingly ready and willing to talk about the club and Crosby himself. It was a contrast from the way that many websites can feel like a barrier to talking directly to a real person (afterall, isn’t an FAQ page just a plea to not call and ask questions?). I contacted the American Vice President of the club, Perry Huntoon, who agreed to talk to me on the phone, and agreed again after I made a time zone mistake. What I found in talking with him was a personal bent toward fanaticism that reminded me of the way my own brain operates. I too am a completist, but for me this tendency has often felt isolating. In Mr. Huntoon, I saw the opportunity for special interest to become a point of connection.

Caryn Aasness: Could you tell me a little bit about Bing Crosby?

Perry Huntoon: A little bit about Bing you say? Okay. Sure. He was basically the Entertainer of the first part of the first half of the 20th century. He did it all, you know –superstar, he was big on the radio, big in the movies. And he was, far and away, the best selling record singer of the time up until probably the time of Elvis, when the rock age came in and changed music so dramatically. But he was also big in the war effort. He was very dedicated to helping out in any way he could. He was too old to be in the service, but did the USO [United Service Organizations] thing.

It’s an amazing story, but he discovered the use of the microphone. That’s what made him so popular and before his time. People were using megaphones or whatever they did. The electric microphone just wasn’t in existence. He knew how to use it. It changed the whole style of popular singing back in the 1920s. Instead of shouting to an audience, like you might hear in an opera setting or whatever, he could hold that microphone up and croon to the audience, if you will. That captivated the world and changed the entire style of male singing. Almost every singer that came along after him in that popular vein took after his style. People forget, they don’t think of him as a movie star. Especially because I think when you go back to the Golden Age of Hollywood, you think of the Clark Gables, the Cary Grants, the Jimmy Stewarts, people like that. But in the second half of the 1940s Bing was the biggest artist in the movies. He was number one at the box office for five or six years in a row. But of course he was singing in the movies. He wasn’t particularly thought of as a great actor, but he did get an Academy Award in 1944 and was nominated again in the 50s. So you know, he had a lot of talents. But the singing is what people remember today. I’m afraid that in today’s age, what they remember best are the Christmas songs because Christmas is in the background, but he was far beyond that. He could handle almost any style— pop stuff, jazz-oriented, Irish songs, old songs from the early part of the 20th century. He could even sing in Spanish or French if he had to. He could do everything and that’s why he had worldwide popularity, he sold a lot of records. He was a comedian too, he teamed up with Bob Hope, on the “Road” pictures(1). They were spectacularly successful. And he could ad lib. He could just speak off the top of his head, make it work— audiences loved it. It was just wonderful.

He was also a technological innovator; he decided after World War II he didn’t want to do live radio. He wanted to do it on tape where they could edit it. He’s the one that basically brought the use of tape to this country. The Germans had developed it, and he brought that to America and that became the industry standard in the later 40s. So performers didn’t have to go on live and worry that they made a mistake or go to a recording studio and cut a record and have to redo it because something got goofed up. You could cut and splice from that, it revolutionized the whole industry. So that’s a brief nutshell.

Caryn: How did you come to know about him? What’s your earliest memory of Crosby?

Perry: I came of age musically, when I was 15. Okay, probably late by today’s standards. A little behind the curve. And at that time, I’m talking 1953, he was still played a lot on the radio. Most top stations would have an hour or half hour devoted to Bing Crosby, I can remember listening to pop music on New York radio stations. From 5:30 to 6:00 on one station, that was Bing Crosby time. My older relatives had Bing Crosby records. I would hear them when I went to their homes, so it was kind of ingrained in me. I just realized this guy had the greatest voice ever. I just took right to it. Everybody was talking about Elvis or the Beatles. I was embarrassed to talk about Bing Crosby, it made me an old fogey living in the past. Now I’m kind of proud of it, you know? I have nothing to be ashamed of.

Caryn: When did you become a member of the club?

Perry: In the mid nineties. I don’t know how much you know about the club, but it originated here in the United States in 1936. Club Crosby, it was called, and that’s the club I joined in the 90s and then I found out almost immediately there was a twin club in England: The International Club Crosby. About two years later I joined that also, because they were publishing things that I was interested in— discographies, glossy magazines and things like that. And then about 2001, the two clubs merged. So we have one now: it’s the International Club Crosby, that’s the survivor, and we date back, as I say, to about 1936. It’s in the Guinness Book of Records as the longest standing fan club in the world.

Caryn: Yeah, that’s pretty amazing. How did you become part of the leadership?

Perry: Well, first I was just an innocent member doing nothing. They had an annual meeting in Leeds, England. I always wanted to attend one. And finally in 2009, I had a major trip planned and I tied that in, and I said Okay, I’m gonna go over there. That’s how I got to meet some of the people. I thought it would be a one time event, but as it turned out, I liked it so well, I went back every year. Then I started giving presentations there every year. We had an American representative that handled things over here for many years, but he had an accident. He was unable to carry on all of his chores and one of the chores was distributing the magazine to the American members. They come over from England in bulk and then we have to separate out the issues into individual mailing envelopes and mail them out. Once he was incapable of that, I volunteered to do that and I’ve done that ever since. Then when he passed on, I just took over the whole shooting match over here, so to speak, and they wanted to call me the American Vice President. That’s where I am. The problem we have is, it’s an aging membership. Bing died in 1977. The memories are getting further and further back and younger people just aren’t aware of or don’t care about him because we’re in a different musical age. So we have an aging membership and a dwindling membership obviously. But they’re very spirited, they’re very enthusiastic. I’m as enthusiastic as I was when I was a teenager.

Caryn: Is there a part of the club that is dedicated towards basically evangelizing for Bing?

Perry: Well, Facebook is one way. There are several Facebook groups devoted to Bing Crosby and our president in England posts almost every day to those groups. And, of course, he promotes the club, offering a free copy of the magazine or a PDF file. I mean this American club started in ‘36, and it was mostly young girls. I don’t think they were called Bobby Soxers back then, but that’s what they were called in the 40s. You know, they just loved certain artists and formed fan clubs. They were just infatuated with the artists and our club kind of started that way too. But it evolved into something much more serious, it’s much more male-oriented now. And people, they’re true collectors, true lovers of music, and they just want to collect it all. It’s amazing. I collect the music, but people collect all sorts of memorabilia that they can find. Whatever they can find with his picture on it or old photographs, old magazines that devote themselves to Bing, whatever. It’s amazing what’s out there. Even ice cream brands, people still have boxes, empty boxes, I’m sure, of the ice cream. So they’re more enthusiastic about doing that than I am. I just want the music; it is my focus. I have a complete collection. He recorded over two thousand songs you know, I’ve got them all, plus a lot that he had only done on the radio or TV or whatever, live performances. So it adds up to a monstrous collection. I probably have close to one hundred Bing Crosby CDs out of my 3,000 disc collection, and they get played a lot.

Caryn: Interesting. So your collection is all on CD?

Perry: Yeah, I went from vinyl records to tape to CD and that’s as far as I can go. People say it’s better with mp3 and blah blah blah, all the streaming. I have too big a collection and I don’t have the time in my life to convert it now. Which is a problem. Cars no longer put a CD player in the car and I play CDs continually. If I jump in the car I pop a CD in. I have an old Sony Walkman and that’s what I take when I do my three mile walk every day and if those things collapse on me I’m dead in the water, so I just hope it holds up for a few more years and that I can buy one more new car that still has a CD player, then I’m happy.

Caryn: That’s the dream.

Perry: It’s just too late for me to make the transition to the new technology. I’m comfortable where I am.

Caryn: I think there’s something to be said about the physicality of a CD or tape or whatever it is. Having an object and having the liner notes, the booklet and everything.

Perry: Well, if they are commercially made, they have liner notes, yeah. In the old days we would buy albums that were 12 inches by 12 inches, so you could fill the back of an album cover with a lot of notes. And I thought, Boy, with a small CD, how do you do it? Well you do it with a booklet now. That works very nicely.

Caryn: Are there other celebrities or topics that you consider yourself to be a big fan of? Have you ever been part of other fan clubs?

Perry: Oh, I have a lot of interest. We have highway groups, right? Driving the old roads, interstates, that kind of thing. And I’m very active in the Jefferson Highway Association, which is an old route from Winnipeg all the way to New Orleans, or the Lincoln Highway Association from New York to San Francisco, and looking for remnants of the old highways— old motels and cafes, and so on, that are not the standard. Every exit now on the interstate has a McDonald’s or Burger King and KFC. No! The old mom and pop places are what we love! I’ve crisscrossed the country. All the US Highways from number one to 101, I want to go from the East Coast to the West Coast and from Canada to Mexico or the Gulf of Mexico. I’ve done them all. It takes a lot of years and a lot of miles, but it’s fun, and we have groups that thrive on that kind of thing. There’s all sorts of varying interests I have, but I think right now, music is what keeps me young. I love it. And I’m compulsive. I’m a completist, you know, when I like something, I want everything of it. When [I’m interested in] an artist, I want everything they ever did. I want to ride a highway, I want to ride it all. I’m just that way, so that’s why I have all Bing Crosby. I didn’t start out thinking I wanted all this stuff. It’s not all totally to my liking, because he did every type of music you can think of, but take it all together and it’s a wonderful panorama.

Caryn: Yeah, neat. What have you learned about Bing Crosby in the fan club that you don’t think you could have learned elsewhere?

Perry: I was focused primarily on the music, and I realized that many members of the club go far beyond that. Film was important to them. I was very casual about Bing Crosby’s movies. Now I have taken a much greater interest and there’s a historical value to it. You’re going back in time, you’re watching the evolution of an artist. That was big. His entertaining on the radio, which was mostly before my time… And I don’t care about their love affairs, marriages, and all that. But in Bing Crosby’s case, how instrumental he was for World War II, or how instrumental he was in the technology of pioneering tape. There was a lot of resistance to that when he did that. Kraft said, No, no, we have got to do the show live. He said, I’ll go to another network, and [so he went to] the Philco show, on a different network. Within two years, all networks fell into line and almost nothing was done live anymore. So those are fascinating things. Historically, quite a bit of interest, and that’s what you learn from interfacing with other people. Because they have their own focus, they can pick up on what they like and kind of run with it. It just broadens and deepens your interest. You kind of cling to each other after a while because not everybody out there enjoys what you do. So when you do you find a kindred spirit? Boy, it’s something a little bit special.

Caryn: So special! What do you think is the role of a fan club in 2021?

Perry: I have no idea if there are fan clubs today even comparable to what they were, because I don’t know the music scene today. I mean, music of today’s age, from really from the 60s on, I know nothing. I mean, I hear some of it, but I don’t care about it. I’m not an expert on it. But back in the pop music days, in the 50s, I can remember there were lots of fan clubs for different artists, mostly younger people. And it was just a form of adulation for the most part. Our fan club is more serious, but the intent is keeping the legacy alive. The number one thing they want to do is keep it alive. They want to publicize, for example, who Bing was– a really important guy and a wonderful singer, a wonderful entertainer, and spread the word. They want to get beyond the Christmas thing and say Hey, he’s good for all seasons.

I grew up on the cusp when rock just came in, you know. The biggest star of my high school senior year was Elvis Presley. And at that point I didn’t care a bit about Elvis Presley. Then, when the Beatles came a few years later, I went back in time and everybody else was moving forward. But the fan club serves the purpose by keeping the name alive. When Bing died, as opposed to when Frank Sinatra died, Bing’s family, his widow, couldn’t do much to keep that flame alive. Whereas the Sinatra people immediately took his name and capitalized on it, to keep it going, going going and twenty years ago. Oh my god, I could run around Chicago and there’s Frank Sinatra on jukeboxes— people are listening to him still, even when he’d been dead for years. That wasn’t so with Bing Crosby, and it was only much later that the estate finally realized they were missing the boat. There was a lot to capitalize on. Not that our club was the total instigator, but the fact that we existed and communicated with them and pushed the issues, I think that helped a lot. All of a sudden, they found archives that Bing had stored away. And they started making sure to do stuff with the public or they got a channel on the streaming audio systems, you know, so you can listen to Bing just like you can with Frank or Elvis. I think all that was a plus. So I think we served a little purpose. We’re here to publicize Bing Crosby and his work. To perpetuate that is our main interest in life and to enjoy it. I mean, whether it’s watching his old movies or putting on the records, in one form or another, that’s our purpose. To spread the joy, so to speak. That’s the main thing we care about.

Caryn: I know that there’s also been things written that have been pretty negative about parts of his life. I don’t necessarily expect you to speak to that, but I’m curious, what do you see a fan club’s role or a fan’s role when it comes to scandalous things or difficult issues in a person’s past?

Perry: Well, yeah, you know, like in Bing’s case, when he died in 1977, within a year, a pair of writers put out a book that absolutely tarnished, almost destroyed Bing’s reputation. The title of the book was, “The Hollow Man.” They were saying he wasn’t what the image of him was at all. They said he was terrible to his children, beat his children, blah, blah, blah, you know. And then his son, his oldest son wrote a book also and elaborated more on that. But he later retracted most of what he said. But those two books really were devastating to the image of Bing Crosby and I read those books and they just washed over me. I didn’t care what they said. I liked Bing for the talents he had and I didn’t care so much about his personal life. But I realized all of this was overstated, and Gary Giddins, the current biographer, has set the record straight on all that. But we do live in a different age today. My God, you know, I wasn’t beat with a strap, but I was sure spanked when I was a kid. Now you don’t even spank a child, let alone anything else. Times change. But I think Bing made up for it. He had a second family and all those kids idolized him, they kept the flame alive very nicely. But yeah, they’ve all grown up to be outstanding citizens as opposed to the four children from the first marriage. Two of them committed suicide, one turned into an alcoholic. It’s very sad to see it, but that’s the sordid side of his personal life. You know, every family has its bad side. Things became a little more public because of the two books that came out after he died. That very much hurt the image. People still refer to that, that he was a terrible father. Today they believe that because they read it once upon a time, and they don’t get dissuaded from it. None of which is true in my opinion. And I’m not an idolizer here, but I saw it for what it was.

Caryn: Okay, that’s interesting. You’re talking about all this information coming out and becoming public, whether or not it’s true about his life. How much information about a celebrity’s life do you feel like we’re entitled to as fans?

Perry: Well, you know, I think today, the internet age with all the cable channels and everything, people like to dig deeply. They go to the checkout counter in their store and see all the tabloid publications there that sensationalize everything. There’s a fair amount of the public that thrives on that. I can’t say that I do. Most of it is misinformation – and hyped up. But how many people are following Britney Spears’ problems, the conservatorship, and all that. I don’t, because Britney Spears means nothing to me. But there’s an element of our society that grew up with Britney. They thrive on all that stuff. I guess it’s been true throughout history. Except that it was a lot easier to hide more of that back in the day, you know, you didn’t have people on your back all the time and photographers chasing you around and all that kind of stuff. But it’s always been there. I pay little attention to it. I guess I could separate the talent the artist has versus their feelings. Elvis Presley for example, a wonderful artist, but my god there’s no reason for him to be dead at age 43. He let himself go and got bloated, got on pills, and whatever, this, that and the other thing, and it just crushed him. Does that change the image the public has? They still love him, they love him! You’re twenty?

Caryn: I’m 27.

Perry: You’re in a different musical world. And I wouldn’t expect you to know anything about the music of Bing Crosby. People almost my age don’t know more than White Christmas. They don’t remember all the big hits because they were too young.

Caryn: Yeah, I guess I know more about him as a performer, as an actor. One of my favorite movies is High Society, and I tell people about it all the time.

Perry: I have a son who is 45 and I brought him up listening to my music at a very young age. And he knew it, he would know Benny Goodman. He would know who Bing Crosby was or whatever. But by the time he was eight or nine he was drifting off into the world that he’s comfortable with and much to my chagrin, it’s heavy metal for him. Metallica, all those groups. We go out, I mean, I’ve been to some concerts with him and I walk out and I’m half deaf!

Caryn: Have you been to a Metallica concert?

Perry: No, I haven’t been. Not the biggest names, but more second tier groups. It was always puzzling to me to walk into an old movie theater and find all the seats have been ripped out. Nobody sits there. You’re just milling around, you could smell the marijuana in the background. But it’s loud. I could get a kick out of it just for the experience, but I’m not going to run out and go play the music on my own. Yeah, and even that music if it’s at a low decibel level in the background, it doesn’t bother me at all because when I go out to the bars, people are playing stuff on the music system. But if it gets too loud, if it gets in my way where I can’t have a conversation with somebody, I gotta get out. I can’t handle that. But my music was loud. Even my favorite big bands, they were loud. But they weren’t amplifying you know, they didn’t amp it up. Because, hey, the brass section can belt out that stuff! An amplified guitar can make a lot of noise. or a drummer that’s amplified. I can remember vividly when rock and roll first came in. I thought it would be gone in a year, because the year before it was the mambo craze and the mambo came and went. I thought rock and roll would do the same thing, and here I’m stuck with it the last 60 years. The early stuff I kind of enjoy, but I don’t care if I ever hear much of it. It bothered me when we’d go to a club with pounding music where you can’t talk. You can’t hear yourself talk and it’s all highly amplified guitars and a drummer. Oh, I got to hate that. Doesn’t anybody remember how to play the trumpet or trombone? But that’s me, and a lot of people my age feel the same way, I’m sure. You adapt to the times and you finally take it for granted.

Caryn: If someone was wanting to listen to some Bing Crosby or watch some Bing Crosby, what’s your number one recommendation? What’s the first thing they should watch or listen to?

Perry: I think there are two avenues. Number one: you can watch a film. Get a sense of him visually; I think that would be important. And a film like High Society would probably be an outstanding bet because it was a later picture, in color and very carefully staged, and if you got tired of Bing, you had Grace Kelly to look at. Or, go back earlier to get the comedy. I would advise them to watch one of the Bing Crosby Bob Hope Road pictures, specifically, The Road to Morocco. That would be a wonderful film. Considered the best. And they were a classic comedy team. But also musically, I would say to seek out a Best Of. The guy had 21 gold records, pretty good sellers. An album that comprises the best of those gives you a very good background of what he was about musically. If you like some of it better you can even veer off into different categories. I like the more swinging stuff. I like stuff where he’s backed by a bigger band, or a little bit jazz-oriented. That’s my cup of tea, but I can listen to it all. And of course, YouTube has all this stuff. I have been amazed at how I could fill out an artist’s repertoire by going on Youtube! I could find the songs that I didn’t actually physically have the record of. Having the toolkit of a computer, you can access all that stuff. It’s amazing. It’s all out there!

Footnotes:

(1) The “Road” pictures were 7 comedy films starring Bob Hope and Bing Crosby released between 1940 and 1962.

Caryn Aasness (they/them) has been club secretary in every club they have ever been a part of.

Perry Huntoon (he/him) is the American Vice President of The International Club Crosby.

Surfing in Maine

“With regards to being paid to surf, it’s more meaningful and respected to work towards being accepted by and becoming a part of the group of locals, than to go pro and be paid to surf.”

– Tess from Maine

I used the $100 to pay Tess, a woman surfer from Maine, to go surfing for a week. This is a conceptual art project where we are both collaborators. I am claiming the action of her surfing for a week as an art project and I am supporting her as a woman surfer by paying her $100 to surf. Similar to the art world, women have been marginalized, underrepresented, and underpaid in surf culture. What form of work is being paid and who gets to be paid? What does it mean to get paid to surf? How does getting paid to surf shift your identity, power, and how you relate to others in a space? How does surf localism filter who deserves power?

Surf localism is what all of my previous artwork is about or was inspired by. It involves usually male surfers who claim a particular surfing spot on the beach as their own, and use power and intimidation tactics to assert their dominance at a place or surf break, filtering who belongs and who doesn’t belong in their space according to oftentimes contradictory or shifting prerequisites. This ties back again to the marginalization of women in surf spaces and colonial practices of white men owning space in the ocean.

I interviewed a person who I will name Tess to protect her identity. Tess is a local, but she is not seen as local by the locals because she does not fit credentials of being angry enough (towards people who live out of town) or other unknown and shifting credentials. She requested to be anonymous to protect her identity and safety in her local surf community. She also had a photographer take photos of her surfing to document the project, but was reluctant to share those photos to protect both her identity and safety, and her local surf spots in Maine. But she thinks it’s super important to have discussions on how surf localism affects personal identity, and that these conversations on surf localism should be made public. With her interest in sociology and different cultures, she had wanted to write about surf localism for a long time. Tess also wanted to mention her support of the women’s surf magazine I started, Sea Together, saying, “It makes women feel like they’re not alone in this man-dominated sport. Now we have our own community of people who also get us, when we all were previously the only woman in the group.” She removed things that she wouldn’t be comfortable having in this interview, like anything that could be perceived as negative by the localized surf spot locals. Tess wanted to add that “references to them being scary and defending the break is something the locals are proud of and something that further protects the break from being surfed by the people they don’t like. It scares people off.” She also ended with saying, “Feel free to use this feature as a way to advertise the rules of surfing.”

In the interview, Tess felt guilty for taking the money; not being paid to surf is seen as the proper way to go and she felt locals would not accept her taking the money. To me, this signifies that to Maine locals, money is power, and they do not want to feel threatened by someone else’s power—let alone a woman who is not a pro surfer. I

Brianna: So, how does it feel to be paid a hundred dollars to go surfing?

Tess: I would’ve done it for free. Donate this money to a good cause. Paying me to go surfing makes me feel uncomfortable.

Brianna: How do you feel about surfers that get sponsored to go surf?

Tess: Oh, well they’re selling their souls. Just kidding. I don’t know. I think getting paid to surf is generally thought of as a sign of making it or respect. And it is fun. I get fun out of surfing. I don’t know if they actually give you money unless you’re a pro.

Brianna: You mentioned respect. So do you feel like if you get paid to surf, people will respect you more?

Tess: I think in one sense or another, you have to kind of earn the right to be paid to surf, except in this instance.

So I think kind of along that path, you’ve gained respect from your surf cohort per se to get recognized on a local or regional or national level sponsorship or through private organizations.

Brianna: How do you feel about me paying you $100 to go surfing as an art collaboration?

Tess: I guess I can see how surfing is art. It is a fluid activity, where you also can’t really judge it. There’s no line drawn between different movements. No movement is done the same way for every person because everyone also has a different body and the way that they react to the wave.

Brianna: Do you feel like it’s similar to dancing or performance?

Tess: Yes. But also no. It is our bodies moving. But instead of our bodies dancing and dancing freely, when we surf, we are responding to the wave.

I guess you could say it’s a collaboration with the wave. Because without the wave, we couldn’t surf. And it depends on what the wave allows us to do on it.

Brianna: I guess it’s similar to art in that it is its own specific medium. Kind of like painting—oil paints only let you do certain things and they prevent you from doing other things with the paintbrush. Or acrylic paint, it dries faster.

How do you feel when people are watching you on the beach?

Tess: On the beach people are always watching the surfers. It’s like we are entertainment for people in a way. Or especially people who aren’t used to seeing surfers; they seem to be more enamored with it than anyone else.

Brianna: So do you feel supported specifically as a woman surfer in the surf community?

Tess: [Long, long pause] I believe that there are marginalized communities within the surf community, which is a subculture. Sometimes women and the elderly, regardless of their surfing abilities, have to prove themselves every single time they go out, even if it’s with the same group of people, to, I guess, earn the right to not be dropped in on. (1)

Brianna: Do you feel that this $100 is supporting you more?

Tess: I feel guilty taking the $100.

Brianna: Why do you feel guilty?

Tess: Because I don’t need to be paid to surf to feel like I’m getting the most out of surfing. I think being in the water is rewarding enough.

With regards to being paid to surf, it’s more meaningful and respected to work towards being accepted by and becoming a part of the group of locals, than to go pro and be paid to surf.

Brianna: Do you feel that you’ve been given the same opportunity as your male sibling in surfing?

Tess: Because I had an extremely supportive father and he had extremely high expectations of us regardless of our sex slash gender.

I was stepping into the same spots as my brother and had to face the same fears. I don’t know. My dad pushed the limits with both of us and didn’t baby either of us.

So in that sense, I had the same opportunities.

Brianna: Do you feel that you have been given the same respect at the localized surf break?

Tess: I don’t surf the localized surf break. So do you mean the same respect at the other break?

Brianna: Yes.

Tess: I feel the same necessity to protect our local spots. And I think by demonstrating that in the water, that would earn me respect if it was seen by the locals. Demonstrating that looks like being angry towards outsiders, being angry towards anyone who is not seen as a local, or yelling at people when perceived as needing to. According to the local culture, people need to be yelled at when they are not from here, or if they are doing anything that’s considered bad in the water, such as dropping in on someone, or if they are not surfing well, or if they fall.

I think my surfing earns me respect in the water. They eventually stopped dropping in on me. I don’t know.

But, I don’t think gaining respect is necessarily a habit from the get-go.

Brianna: Do you feel like they would be supportive of you being paid a hundred dollars for surfing?

Tess: No.

Brianna: Why not?

Tess: I think they think they should’ve been paid a hundred dollars.

Brianna: Why?

Tess: Misogyny.

Brianna: Did it feel like work surfing for a week? Do you feel like you worked hard to earn the hundred by surfing?

I’m just really interested in people’s idea of work, what is worthy of being compensated as work.

Tess: I don’t know how to answer this. I mean like today, for example, I guess I was more willing to wake up early for dawn patrol (2) because I knew the session was going to be photographed. And I was surfing to get paid and we were going to have an interview. So I felt more of an obligation, slash there’s a chance I would not have woken up for dawn patrol if it wasn’t partially work.

If I wasn’t going to let you down, I’m not sure I would have had the willingness to wake up this morning.

So in that sense, I guess it was, I guess there was some feeling of, this is more like work.

I think any time you’re being photographed, it feels more like work. You have to kind of give everything that you’ve got to try to get good photos and get as many waves and do as much on each wave as you can, because a lot of your waves are going to be missed (by the photographer).

In contest surfing, when you’re surfing for a prize and there’s limited time, it definitely feels more like work. And I think sometimes, I get more energized in that situation. I’m less chill and more… not aggro, but like whatever it takes…I push myself harder than I normally would.

And I imagine that for pro surfers, everytime they go out, their job is essentially on the line. That would add a significant sense of responsibility and intensity and urgency.

If you have all the time, I think on some level you can risk your love for the sport. I just think there is a rejuvenating aspect of getting into the water without expectations.

Because I feel like, normally every time I get into the water, I never want to get out of the water. I never think, Oh, I wish I hadn’t gone surfing.

Brianna: I remember one day this guy was yelling at me and calling me stupid for protecting the puffins. And I went to surf after and it was crowded. And the same guy was in the water and in my way three waves in a row. I raised my voice a little bit and said, “If you need to paddle back out, you need to paddle around again.” And looking back, I just feel guilty about that. You know?

Cause other people saw me and maybe I thought, They’re thinking, Oh Bri isn’t being like her positive self, you know. I was trying to both stand up for myself and also educate this guy as he probably didn’t know what he was doing maybe.

Tess: And it’s a safety concern too.

Brianna: Totally. It is a safety concern. I guess there’s this discrepancy, which ties into surf culture. There’s people that think you can’t do that or say that (like what I said to educate the guy). And then there’s people that are like, Oh, that’s what you’re supposed to do. It’s like skiing. You can’t just go to a double diamond trail and think that you can do that if you’ve not reached that level before.

Also, sometimes I feel the pressure that I have to always smile and talk with everyone in the water. But, sometimes I want to just go and surf. Surfing is like a meditation for me.

I don’t want to have to say hi to everyone all the time.

Tess: I think I feel maybe the opposite end of that, where, I need to go out and be more aggro and just be super, super good. And when I’m having an off day, I just feel that I can’t justify being an asshole—not that I am an asshole on any level—but I can’t justify glaring at people ever. It’s hard to not only balance the part of that protective side of myself, the part that says I want to fit in as a local or I want to make the locals proud, but also go out there with no expectations, to have a good time and be happy. Which I feel like I end up surfing better in the latter situation anyways.

And then when people are actually being stupid and unsafe and, you know, ruining great waves for so many other people… Even if you’re nice to them, and you try and redirect them, I feel that they’re less likely to listen because you’re a woman and you just feel guilty about it afterwards.

Brianna: Yeah. I think there’s like this expectation, you know.

I try not to engage with new guys in the parking lot anymore, just because I don’t really want to deal with them trying to date me. And I know that’s not always the case, but I think I got kind of burnt out on that experience repeating itself many times in a short period. So now, sometimes I don’t say hi to random strangers and smile at them because I’m just tired of it, you know? There’s this expectation for women to always be super happy and smiley and give their energy to everyone, you know?

Tess: Yeah. That’s totally an expectation.

Brianna: But then if like a woman surfer is in the parking lot, and then she doesn’t say hi or anything, or just keeps to herself, then I feel like she’s seen as a bitch or something, you know, but men do that all the time. There are so many guy surfers I know that don’t say hi and they just keep to themselves.

Tess: Maybe it’s because I was always out with my dad and my brother. I don’t know. I would hate to talk to people. When I’m out surfing, I’m out to surf. I hate when someone’s talking to you and you feel this in the water, and the set is coming up, and you’re thinking, I need to reposition so that I can get this sick wave.

Brianna: So going back to localism. You were born here, but you mentioned before that you don’t see yourself as a local.

Tess: Guys are pissed at me and they just look like they’re fucking pissed because I’m longboarding. (3) So I’m sitting out on them and then getting the biggest wave set and then yelling at them if they try and go for my wave.

Brianna: Good.

Tess: You definitely can’t just be born here [to be a local]. You have to have the talent [to be a local]. And then you also have… It’s like rushing a frat (to become a local).

You have to prove that you will defend the localized spot, and all of our spots from kooks and from tourists who come in and think that they just own shit because they’re a straight white male and they rent a surfboard, you know? And they’re fucking terrible idiot assholes.

You’d have to prove yourself in that sense too. The locals want you to be mean, you have to be mean when it might be deserved to protect the spot.

Brianna: And then you’re saying you’re only a local if you surf the localized spot, correct?

Tess: Yeah. And it’s just the guys who surf the localized spot, and sit at the beach at their locals-only spot and cheer for their homies, the other locals, and then just heckle everyone else.

Brianna: It’s like a game.

Tess: It’s 100% a game. No one knows who I am.

Brianna: Why don’t the locals know who you are if you were born and raised here and grew up surfing here?

Tess: No one knows who I am.

I feel like I’ve been hidden away or just cause I don’t surf the localized spot… There are the stories from everyone of the dangers socially and physically from surfing the localized surf spot. The rocks aren’t the most dangerous thing.

Brianna: So the people are?

Tess: Yeah, you could legitimately get the shit beat out of you.

And I know, as a girl, that’s not gonna happen, but anytime that someone is yelling in the surf, or even if they’re just talking loudly—because no one can hear with their hoods up—to their friends and joking around or whatever, I’m always scared that they’re yelling at me or telling me to get out of there. As if I don’t deserve to be there or something. And I think being at the localized surf spot, I know that they would yell at a girl. They still yell at you, but they probably won’t punch you as a girl.

Brianna: How did you feel surfing other spots in your home area?

Tess: I kind of just turned it into my own spot and try and earn my stripes, but obviously all the people at the other spots are a lot more chill and I feel like we’re just like a big family, you know, I love that.

In my general localized area though, there’s a hierarchy in the water. And if you don’t know who your senior is and you disrespect them, they’re going to do everything in their power to make you suffer. You don’t want to be the bad apple.

To wrap up this interview, I want to share a few quotes about localism from women surfers around the world from ISSUE 002 of Sea Together. You can check out Tara Ruttenberg’s article in ISSUE 002 of Sea Together, titled Does localism redress neocolonial privilege in Global South surfing destinations? You can read more on my work about surfing in my graduation publication; feel free to email me for a copy at bri.ortega.m@gmail.com

– Brianna Ortega

“Localism to me is having emotional and physical ties to a given spot, after putting in the time to gain respect from others doing the same. Localism can be good by enforcing etiquette in the water, and by inspiring a love for coastal conservation in a given area. Localism can be bad when people use whatever reason they feel local as an excuse to simply be an asshole, as in acting above etiquette rather than leading by example.”

– Lauren

“I don’t see localism as a positive. But being a local and enjoying your break with others is awesome.”

– Terri

“As someone who’s only been surfing for a few years, I’m still terrified of localism. Despite not having experienced any incidences so far, it’s always in the back of my head–especially as a girl who surfs by herself.”

– Emma

“I’ve been a local and also traveled to places where localism was downright dangerous. Really the root feels like a call for ‘respect’ in the water. We can have a long talk about rules and etiquette, but in the end it’s about recognition and earned respect.”

– April

“I’m ok with localism. It is a big part of the roots of surf culture and I don’t think it should die.”

– Sabrina

“I believe localism is best used when it protects and betters the community. For instance, when ‘locals’ put pressure on individuals who disrespect said place and/or the people within it (i.e. stealing, harassing, urinating, and defecating in public areas, etc…).”

– Carla

“As much as I despise the localism often displayed at surf breaks all over the world, I believe it’s a tricky topic. Localism should protect and better the community, and also not harm the environment. I’ve had many talks with Kala Alexander and other locals on the North Shore as well as in Maui, and while I don’t agree with how that localism is sometimes executed, I understand why they are protecting their breaks so harshly. It’s a fine balance. The professional surf industry has often chosen spots and put on contests without enough communication and involvement with the community, which leaves a sour aftertaste. They are now slowly addressing the problem and seem to act more responsibly. Some localism is unacceptable, and we’ve seen the results (even if it took a very long time) in our backyard not too long ago (Lunada Bay).”

– Zora

“The only locals are the marine animals. Seriously though, stewardship means more than localism to us. If you’re a steward and taking care of your spot in all the ways that preserve it for the future, that service means way more than localism protectionism in the name of ego.”

– Katherine

“I feel like localism is there for a reason; when a local yells “GO” on a set wave, you bet your ass I better catch that wave. When a local has been surfing the same break their entire lives, they automatically have first dibs. However, it’s common courtesy to share the waves. When it’s super crowded, I believe it’s okay for locals to play the ‘local card.’ It’s not okay when locals get super territorial and start fights, especially if the waves are small! I think it’s best to always salute the locals when you paddle out and share your gratitude.”

– Thespi

“I’ve been surfing Cardiff Reef for just over two years, and last week I pulled up in my car just to look at it and a local who has been surfing this spot for 40 years sees me, walks over to my car, and says, ‘Definitely go out. It won’t get any more windy than this, trust me.’ He was right. I had an epic session that afternoon, in gratitude. How blessed I felt to receive that wisdom. That’s the best of what localism means, isn’t it? One generation learning from the next, the wisdom of the elders.”

– Kaia

“I feel quite strongly that localism is okay in very few instances. I surf in the Pacific Northwest (U.S.). It’s cold. I’m a beginner and trying my hardest as an adult woman to get into the sport. When I go to spots in Washington and men give me dirty looks and just seem annoyed I’m there, I get it I guess. I think I understand when the lineup is extremely crowded, that locals would want some [waves] to themselves, but I think that should be a time to teach people about surf etiquette and just invite them to learn more about the sport instead of starting fights or making faces. Especially up here, I feel there should be a bit more understanding of what we have to do to catch waves. Most people are traveling to catch waves and so most of the time there is no big local surf scene. It’s just frustrating driving hours, trying my hardest to get just one wave at least, and then getting dropped in on by someone every time who assumes that because they are better they get unlimited access to every wave.”

– Audrey

“Localism is ridiculous!!! What does it really mean? That only locals can surf all the waves??? The only local/owner of the ocean is GOD!! Respect is the key and many times locals are not respectful! If you don’t respect, you can’t ask to be respected! Localism sucks!”

– Audrey

“Localism is rubbish. Not everyone has the privilege of living on the coast, but they are still drawn to the ocean. Sure, it’s annoying when you have perfect conditions on a long weekend and the peaks are crowded, but no one has dominion over the waves. Just because someone isn’t a local, it doesn’t necessarily mean they are unsafe. There are plenty of arrogant locals making bad calls, as well.”

– Jenny

“The term localism gets tossed around frequently in L.A., and I simply see it as an intimidation tactic. People warned me about Topanga for years, so I stayed away for that reason, but then finally got the courage to surf there and have had many wonderful sessions and met some amazing and welcoming people. The key for me is to be patient when I surf a new place–pay attention to where the wave breaks, the feel of the crowd, and observe for a bit. I don’t roll up to a new spot and pretend I already know everything; there is something to be learned from each other and you can usually read individuals in a crowd, and who is approachable. I’ve also had those idiots at Topanga say ‘I’ve been surfing here 20 years and never seen you.’ Ok buddy good for you, want a cookie?”

– Stacie

(1) Dropped in on means when a surfer takes someone else’s wave by paddling into the wave and getting into the other surfer’s way.

(2) When you wake up early to go surf, usually at dawn or before dawn or after dawn, depending on each surfer’s unique relationship to how much earlier than normal they can tolerate waking up.

(3) The original type of surfing from Hawai’i, where you are on a larger board and you paddle into waves sooner than people who are on shortboards, so technically you can get more waves overall because you have to sit on the outside.

Brianna (she/her) is in her third year of the MFA program in Art and Social Practice at Portland State University. Through embedding herself in surf culture, Brianna Ortega uses art as a tool to explore the relationship between identity and place through questioning power in social constructs and physical spaces. She values making art in relationship with others at the global or local site. She engages with topics of gender, race, Otherness, place, and the in-between spaces of identity. Her work is multidisciplinary, spanning across performance, publishing, organizing, video and facilitation. www.briandthesea.com

Tess is a surfer who lives in Maine. She wants to be unidentified to protect her local identity as a surfer.

Talking About Trans Boxing

“When I look at the Trans Boxing class on Zoom in the grid view, I’m like yo, this is deep. It’s really dope. I think it’s a way of actually creating that representation within our group that we’re looking for outside.”

– Eleadah Clack

In the fall of 2013, when I was an undergraduate student at the University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee (UWM), I took a course with Dr. Shelleen Greene called Multicultural America. As part of the class, we worked with the Pan African Community Association (PACA) – a non-profit organization on Milwaukee’s north side which offers after-school programs and assistance to African immigrants and refugees. Throughout the semester, each UWM student paired up with a PACA student to create a collaborative digital storytelling project that shared their stories about migration and learning new cultures.

The collaboration facilitated an engagement with members of the community that I wouldn’t otherwise have had—and it also supported a deeper understanding of the ethnic studies concepts and theoretical frameworks I’d been introduced to in the class. The student I worked with was named Juma, and the experience of working with him had a lasting and profound impact on my life as an artist.

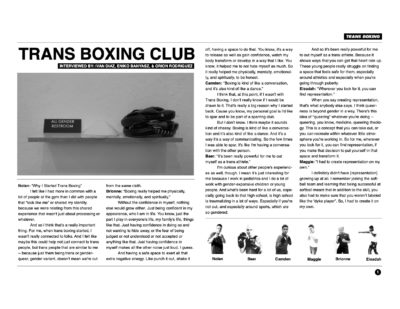

This term, I designed and taught my own class at Portland State University (PSU), an opportunity offered to me by Harrell Fletcher, the director of the Art and Social Practice program where I am completing my MFA, and made available through the advocacy and work of Ellen Wack, an Administrative Coordinator in the department of Art and Design.

The seminar class, called Relational Art and Civic Practice, is designed to support students with conceptual development as well as in-practice application of the strategies involved in socially engaged art projects. In addition to lectures, readings, and discussions, I wanted to give the students hands-on experience with a project.