Did You Play in the Creek?

June 7, 2023

Text by Morgan Hornsby with Wendy Ewald

“Whatever I did came from exactly what was there.”

Wendy Ewald

My favorite Wendy Ewald image is one of and by Denise Dixon, taken in Letcher County, Kentucky. In the black and white photograph, Denise is wearing a sundress and a tall, light wig in what looks like someone’s backyard. A dog scurries under her feet. She looks both comfortable and performative. The caption: “I am Dolly Parton.”

When I see this image, I think of the archives my grandmother has of our family’s life in eastern Kentucky, their backdrops often similar to the rolling hills featured in this photograph. I think of my own childhood there, chests of dress up clothes and hours of make believe. I think of the beauty of the eastern Kentucky landscape and, of course, dreams.

As a photographer and Kentuckian, it was a dream to talk with Wendy about her experiences living in Kentucky and what she gains from working collaboratively.

Morgan Hornsby: First of all, thank you for being here and talking with me; I really enjoyed the conversation we had in class last week and getting to hear more about your artistic process. I wanted to start with asking about something totally different. As a person from eastern Kentucky, I’ve always wondered about how you liked living there. What did you gain from living in that place?

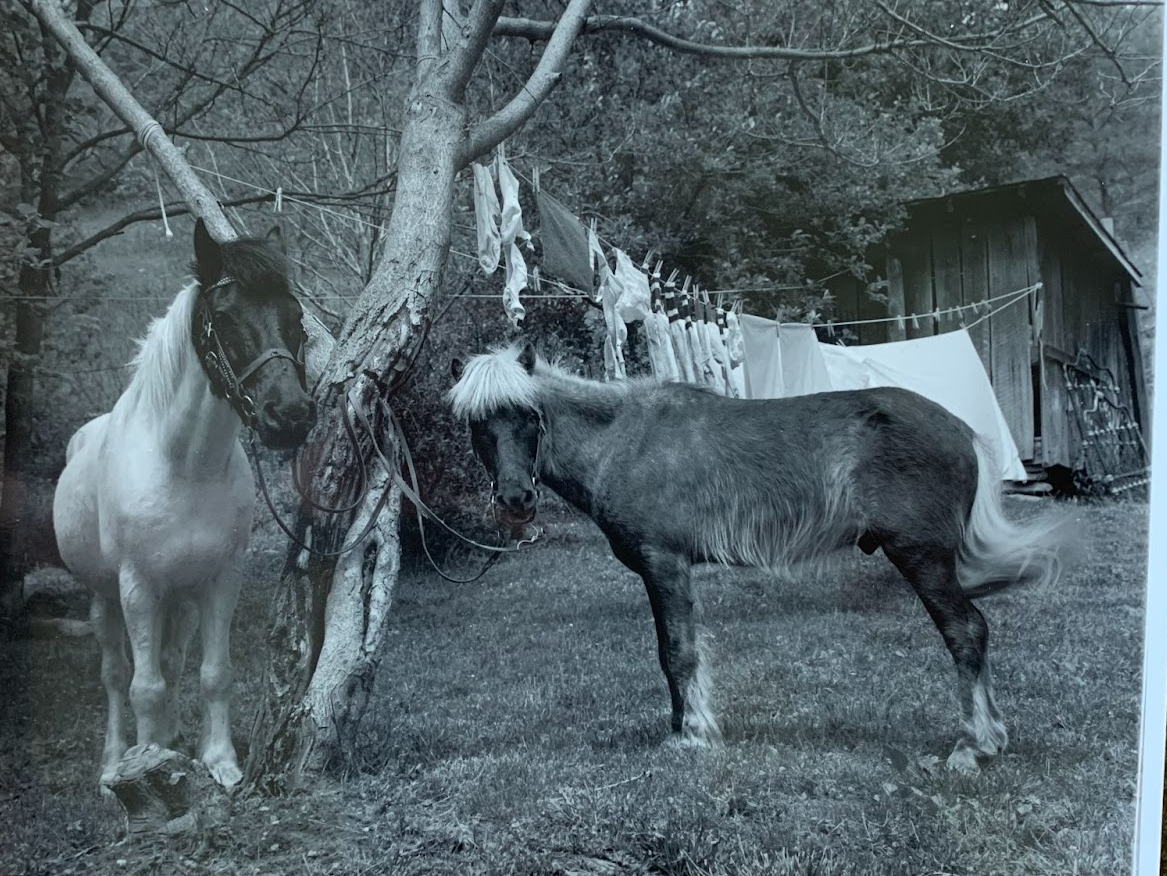

Wendy Ewald: It was really, really important. I always wanted to go to Kentucky. I knew about Frontier Nursing Service and Berea and when I graduated from college, I went to work for Appalshop. I went with my husband, and he started the theater there, with their roadside theater. So it was fantastic to drop into this group of artists of all kinds. Before that I had worked in Canada, so it made a lot of sense to me. It wasn’t easy, as you know, to find a place to live at first, because we were from the outside, but we eventually rented a house on Ingram’s Creekand became a part of that community. And that’s one of the things I really liked too, because we did things like grow corn with our neighbors, and we made molasses, nobody had made molasses there in many years. It seemed like a complete way of living and being an artist, you know, being part of all that. I did that for five years, and I worked in three different schools. I just learned a whole lot. I mean, I figured out my practice in a way. Yeah, not in a way, I figured out my practice there.

Morgan: What was your house like in Kentucky?

Wendy: Oh, well, that’s really a good question. Because I first lived in a little house, and this is all on Ingram’s Creek, but we rented it. I think it was $50 a month. We knew all our neighbors really well. And then we decided we wanted to buy a house. There was somebody who wanted to sell us their farm which was 30 acres or something like that. It had some bottom land and two houses on it. And so we bought it and rented out one of the houses there and were there for five years. And you know, we grew sorghum, made molasses.

Morgan: That’s cool. My family made molasses too.

Wendy: No one had done it in Ingram’s Creek in such a long time. It was a big deal for everybody. I wish I could get some last molasses! Does your family still make it?

Morgan: They don’t make it anymore.

Wendy: Ah. It’s so good.

Morgan: How did you spend your summers there?

Wendy: Well, we had a big garden, of course, we had animals. We were outside all the time, we went to the creek on the weekend to swim. We had outdoor parties.

Morgan: I really wanted to know if you played in the creek when you were there.

Wendy: Yeah, definitely.The whole thing of learning how the landscape is defined by the creeks, where the hills meet and all of that. I just learned so much about all these deep, meaningful things that I hadn’t experienced.Where did you live?

Morgan: I’m from Jackson County. It’s near Berea.

Wendy: Which town?

Morgan: My family lives in Sandgap, but the county seat is McKee. So I lived there, and in different places, but right now I live in Tennessee. Something else I wanted to know related to your work in Kentucky–on your website, you describe your aim for Portraits and Dreams as for the children you were working with to “expand their ideas about picture-making, while staying close to the people and places they felt most deeply about.” I was really struck by the phrase “staying close” the first time I read that description and have thought of it often since. Do you have any other thoughts on the idea of “staying close,” or of the way photography has of doing that?

Wendy: Well, I was trying to figure out how to do that, but I really did develop it there. I wanted them to learn how to start from themselves, self portraits, and then move to their families and then their community. And after that, more expansive things, like their dreams and fantasies. And then later on I went to do other kinds of projects, but that was really the basis of it. So it was a gradual kind of moving from the child, you know, out into the community and eventually to dreams and fantasies. And I don’t know, is that what you meant?

Morgan: Yeah, I think so, I have always just liked the instruction of staying close. Growing up, I sometimes felt like having aspirations of having a creative career separated me from the people around me. For that reason, I am really drawn to the idea of using art to stay close, especially in the context of eastern Kentucky.

Wendy: Yes, yes. And for me, working in those schools really helped to understand that. Because I was living right near all of them, we would see each other on the weekends and do projects together and stuff like that. Whatever I did came out of exactly what was there, both in terms of composition and landscape and in terms of topics. I think that’s the most important thing I’ve done in my career, to try and stay close to wherever I was. Even though I didn’t necessarily know it, I tried to get them to help me.

Morgan: I like that a lot. As a photographer, what do you feel like you gain from giving up the complete creative control that you yourself are making the pictures?

Wendy: Oh, gosh, I gain so much as an artist from that. You probably know what I’m talking about. But because when I went through school and went through rigorous photography classes, like at MIT, it was great, but it wasn’t necessarily mine. And it wasn’t necessarily the places where I was. Although it was good to have as a background. So when I went farther on, it also gave me some space to try different things and to try different techniques and use materials in different ways. And so part of it was pedagogical, but it also as an educational tool it made sense. So I was always trying to make up things that made sense in both ways, in education and then creativity.

Morgan: What do you feel like you’ve learned about yourself through the kind of creative process that you’ve chosen?

Wendy: Well, I’ve learned to look and listen, and to understand that I have preconceptions always, and to learn to let them go or be transformed by the situation. That is also very difficult sometimes, and I feel like I’m not doing the right thing. but I just have to wait it out until I start seeing and understanding.

Morgan Hornsby (she/her) is a photographer and socially engaged artist from eastern Kentucky. She currently lives and works in Tennessee. Her work has been featured in the New York Times, The Guardian, New York Magazine, NPR, Southerly, Vox, and the Marshall Project.

Wendy Ewald (she/her) has collaborated on photography projects with children, families, women, workers and teachers for over forty years. She has worked in the United States, Labrador, Colombia, India, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Holland, Mexico and Tanzania. Her projects start as documentary investigations and move on to probe questions of identity and cultural differences. With each situation, she uses different processes and materials to shift my point of view and engage with my subjects. Her work may be understood as a kind of conceptual art focused on expanding the role of esthetic discourse in pedagogy and creating a new concept of imagery that challenges the viewer to see beneath the surface of relationships.