Illustrations: The Ordered Steps of a Cultural Worker

April 3, 2021

Text by Justin Maxon and H. “Herukhuti” Sharif Williams with Desire Grover

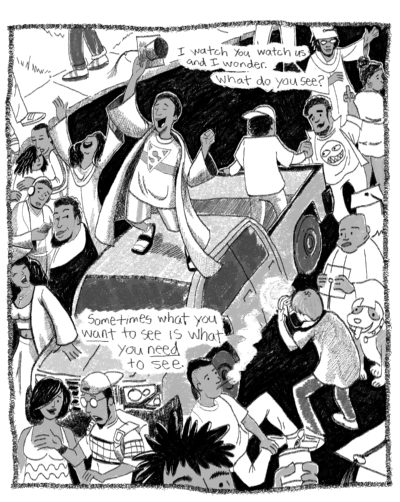

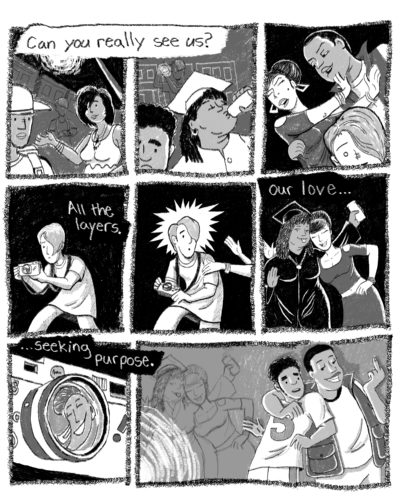

“So, the white gaze in many ways can be an act of power. I’ll see you when I feel like seeing you. And if I am looking at you, it’s because I’m watching you. Or if I am looking at you, you need to perform for me. So, I feel safe.”

Desire Grover

This interview, conducted through email, is a collaboration between H. “Herukhuti” Sharif Williams, Desire Grover and myself. It is a part of an ongoing dialogue and serves as an entry point into a project we have been developing. Since 2017, Williams, Grover and myself have been working on a collaborative book project titled Chester: Staring Down the White Gaze. At the epicenter of this critical collaboration are two sets of images: the work I completed as a photographer and journalist, covering the city of Chester, Pennsylvania from 2008-2016, and photographs from my childhood archives. Using the latter, we built a visual glossary of white racial tropes to unpack my relationship to whiteness. We use this framework to reconsider my work in Chester, along with other contemporary and historical local media coverage of the city, to elucidate the ways the white gaze reflects its own values when reflected off of the bodies of Black people.

Chester: Staring Down the White Gaze will be published as a collaborative book project of co-authors from the city who tell their own narratives: Desire Grover, illustrator; Wydeen Ringgold, citizen journalist; Leon Paterson, self-taught photographer; and Jonathan King, activist and educator. Throughout the pages of the book, the co-authors are in conversation with Maxon about his images through handwritten text that analyzes, critiques, questions, contextualizes, and interprets the nature of the white gaze that is placed on their community.

Justin Maxon and H. “Herukhuti” Sharif Williams: When did you know you were artistic?

Desire Grover: I realized this when I was very young, maybe as young as five. I loved to color and draw. I consumed paint-by-number kits as a child. Spending hours alone writing and drawing comics was like breathing for me and it still is something I love to do despite all of the responsibilities that try getting in the way.

For a season, life happened and I was doing freelance art that was very sterile and didn’t require much creativity and I was working side jobs. I also stayed busy doing community work for over a decade and it robbed a lot of my time being truly focused on art. It’s only in the past seven or so years that I’ve reclaimed art as what I do and who I am. Not everyone in the community knows me as an artist. Most know me as an independent activist journalist. My art in mural painting was something that came later. I’m continuing to shift into a more personal expression of myself as an artist. I’ve primarily done community art but in the last four years, my focus has gone inward. I’m determined to focus on creating comics and graphic novels. It’s partly why I’ve started attending seminary. I’m working on an MA in Theology and the Arts at United Seminary. My love for Christ is what catapulted me into community service and my art has become a way to help me make sense of those years. I learned so much about others and myself and I’d like to share these experiences more broadly.

Justin + Herukhuti: Do you tell people you’re an artist? How did you come to the point of being able to call yourself an artist?

Desire: There’s a little bit of a yes and no to that. Growing up in the city, in my school life, everyone knew that I was an artist. So that wasn’t really something that I had to tell people. I don’t really like necessarily calling myself an artist. I like to be a little more specific when it comes to what I do. I’m an illustrator and illustrators tell stories. It’s really about the effectiveness of telling a story that helps you stand apart from just being labeled an artist, which is partly why I’ve had some difficulty in finding my single voice. Oftentimes, I’m accommodating to a customer’s needs and what it is that they’re trying to convey in their story. So being myself as an artist is not something I’ve always had the privilege to do. It’s only now I’ve become much more focused as an artist on what my voice is and what my story is. And now I’m actually exploring my past and how it has brought me to the present. My faith in Christ was a big part of my life. I was very zealous in my younger years, which is why I was so heavily involved in activism. My devotion to Christ was really intense.

I don’t even know how I kept any friends during college really, but my college years were probably the most zealous years, and I would hit someone over the head with the Bible, big time. Even in art school of all places, but that’s changed a lot— life hits you, you start to see the consequences of a world in pain. You start to experience trauma from that world in pain, and it changes your perspective. I think it changed my perspective being able to see people’s struggles up close and not just make assumptions about folks who were going through something.

Talking about what I want to talk about and not what a client wants is a new space for me. I figured the story I should start with is really a story that I know well, and that is a story about myself. So, people saw a progressive liberation theology being played out in my life. At the time, I didn’t know that’s what it was called. I just knew that I wanted to be of earthly good.

Sometimes this got me into trouble because people couldn’t pin down what my motivations were. I did get the impression over time that some folks got involved in community work to maybe start a professional career as a social worker, complete a college project, or they were trying to become a minister, and others to start a political career. But my motivations were very naive, like, well this is what Jesus would do. This is where Jesus would be. It was that simple. Some of it had to do with me not having a clear goal beyond solving the problem at hand. I could be pretty callous to how I came across to people because I thought I was working for a higher good. I’m on earth now so that’s changed. Hopefully.

Justin + Herukhuti: Who do you consider to be your primary audience? For whom do you make art? Does that audience change depending upon the subject matter or form of the art?

Desire: I think I’m talking to those who are questioning their purpose on earth. Those thinkers who are concerned about, “Why are we here?” I also think I’m talking to folks who might want to stop for a moment and recalculate why they do what they do, and why they believe what they believe, because I know that’s what I’m drawn to, artwork and writings that pull me into a place of contemplation. There are times I’ve tried to write stories for young adults, but I find that it can be limiting to really be that targeted on an age group or a demographic. I don’t know if I can really accomplish that. I haven’t traveled enough to say that I’m worldly, but I think I do have a tendency to think more broadly about the diversity of an audience and that a lot of different people can appreciate the same thing. You know, you definitely wouldn’t want me on the marketing team.

Justin + Herukhuti: Have you ever felt pressure to protect the status quo in your art?

Desire: When initially breaking into an industry like illustration, to be marketable as an artist on a larger scale, I would say yes. Both the broader audience and art directors tend to want art that has commercial appeal and is non-political. When doing community art, the same pressures may exist despite the noble message that some pieces are tied to. I tend to avoid painting people in general due to the human need to decide on whether an art piece is for Black people or white people etc. It can get heavy pretty fast when it comes to identity politics. If I do paint people, I prefer historic figures that are tied to a very clear message and/or context. It makes it more difficult for people to hijack the meaning of a mural when the figure involved is very specific.

Justin + Herukhuti: What began your relationship to Chester as a cultural worker?

Desire: When we first moved to the city of Chester, I was very much to myself, very insular. I didn’t really engage the community much, beyond a very small circles of friends and my church life. When my father briefly took over leadership at Chester Church of God, that’s when things became more intimate. But I wasn’t necessarily with my peers. I was spending a lot of time with older people in the church. But later, because of the gun violence in our neighborhood, our entire family was pretty much shocked into action. I don’t see what we did as courageous or anything like that. Actually, in a shameful way, we knew that gun violence was happening. In the Highland Gardens more specifically. It’s unfortunate that it took a young man getting shot in front of our home to move us into action. Thankfully we did and that’s how my engagement in a more intimate way with the community started. I understood that if I didn’t care about the community, I didn’t care about myself. I wasn’t out there just to be loving, I was scared of the gun violence and what it was doing to my peers. I went to school with some of the people that died. I knew the conditions that some of them lived in were not ideal. They were very harsh.

It’s really heartbreaking and frustrating when people talk about the city, but they don’t have knowledge about what’s actually happening within the city. It can feel very insulting, but at the same time, I know that they’re ignorant of what’s actually going on. Chester is not a place where gun violence is just happening all the time. There’s a lot going on in the city that’s beautiful. I got a chance to participate, to see and understand what’s really the pulse of the city, the work to make sure that children are safe, to make sure that people have access to education, the fight for meaningful work and a living wage. The women of the city are just phenomenal. You know, I do have some biases as a woman. The women of the city do a lot of the work without fanfare. They’re not as concerned about titles. It’s impressive the level of sacrifice that goes on that no one knows about when it comes to the women of the city. It’s hard not to have a heart for Chester once you engage the people. It impacts you. It stays with you. I had so many great people around me. Reverend Warren was one of the first, along with Jean Arnold, Nicola Jefferson, Dr. Willis and Ieasa Nichols. Their passion and their drive to really work hard, especially for the young people. If I could write a thousand books, I would, but I can’t.

Justin + Herukhuti: As a community artist, tell us about an experience you’ve had that has taught you something about power that you have found really meaningful?

Desire: Wow, where do I start? I learned the importance of thinking ahead about relationships and the importance of being very intentional when it comes to relationship building. This goes beyond being a community artist. I think the road that I traveled was bumpy because I had come into the scene to address the gun violence and to help with that. I was dealing with politicians locally in a more antagonistic way. Actually, my skills as an artist were really in graphic design and web design. I did blog about the things that were going on, and that did cause me some problems with political figures. They were not used to that level of scrutiny up close, especially from someone who lived within the community. I think it can feel very jarring and they can get defensive. I had to learn the hard way that you gotta think about where you leave people mentally and emotionally, no matter what your intentions are. Even if you’re right about what you’re challenging them for, you have to think about how you leave them as a person, because leaders are also human beings. I’m much more aware of that now. I wish I had an understanding of that earlier in the process. I could have saved myself some trouble.

Justin + Herukhuti: From your perspective, is cancel culture a worthwhile discussion to have as an artist? What methods of engaging in a socially responsive context do you see working in the city of Chester?

Desire: I think this is a worthwhile conversation for the artist who wants to use their art as activism. The possibility of being canceled is very real and should not be taken lightly. I wish that I understood this in the beginning as a young artist. Idealism can be a blinder. Before an artist jumps into using their skills to critique or challenge power in a community, large or small, they should assess what the outcome will be regarding relationships with local leaders in the long term. These persons will have sway over the community and other leaders. Art as activism, if done relentlessly, can reap negative consequences, so building positive relationships with influential community members is important.

I think most local artists wisely play it safe because they understand certain relationships and dynamics better than an outsider might. Although I partially grew up in Chester, I was still a bit of an outsider. I did not have family ties or history there that could have better informed me about the dynamics. And in hindsight, there are some things I should have passed over to an artist who had those local ties and history. They could have steered me in an informed direction for sure. I was young and idealistic then, so I forgive myself.

It’s important to take time to listen and observe so that you can understand how the community sees the leadership among them. Unfortunately, there may be times you come across certain characters in leadership that are really toxic to the community and you must make a decision on whether or not it is advantageous to point the toxic behavior out. Sometimes the community is not ready for that level of critique of someone they know intimately, and you may end up doing more harm than good when challenging the leadership. In short, it’s good to learn when to step back and clarify what your role is as an artist for the community before reacting. Now this might sound intense, but it all depends on what you are doing with your art in the community that will determine if the things I describe will ever even be an issue for you. Again the way that I ended up on the scene was not through a happy-go-lucky program but rather the jarring experience of addressing a very disruptive experience with gun violence in our neighborhood.

Justin + Herukhuti: How does Chester’s relationship to the County speak about bigger issues of race and power in America?

Desire: Growing up in the city I got the impression that the County at large treated Chester very much like Judea treated Nazareth (John 1:46). If you know anything about that time and space, Nazareth was looked down on. I think the County makes the mistake of doing the same to Chester. One of the remarkable things about the city is that it produces a lot of great thinkers and athletes and I’m willing to bet this has a lot to do with the negativity that is posted about the city in the local news. The local media does print a lot of the good things going on in the city but unfortunately, people from the surrounding towns do not leave comments on those articles of the Delaware County Daily Times. They respond almost exclusively to articles that have to do with gun violence. The comments are very racist and offensive. Despite all of this, there is a lot of pride in the city in overcoming the odds and working past the negative stigma from the surrounding areas. The community has a term we use to describe this resilient disposition. It’s called C-Pride. There are other sayings and phrases often used by grassroots activists who live there. One of the most popular is “What Chester Makes, Makes Chester.” This particular saying has a lot of depth to it because it not only speaks to the achievements accomplished in the present day by Chester residents, but it reaches back into the past reminding residents of Chester’s historic significance. You may notice that I speak both as someone who lived in Chester and at other times my wording is as if I am an onlooker. One of the reasons for this is because my family moved to Chester when I was in my teens, so I try to be careful not to overspeak my ownership of Chester’s greatness. Being born in the city has a very particular honor to it and I try not to cross that boundary.

Lastly, I believe the grassroots movement around education has been the most powerful force for dynamic change in the city. It helped so many of my peers and myself. The school system has struggled for years with very little resources, yet because of determined residents and community leaders they have been able to provide meaningful access to education despite the insane challenges. Again, Chester’s resilience is remarkable and the ability of young people to strive and move forward is something that should be applauded.

Is there more that MUST be done? Yes! But what has been accomplished despite the odds is astonishing!

Justin + Herukhuti: What roles have race, gender, and class played in your experience as an artist?

Desire: Well, as a Black person, especially in the industry of illustration, I do feel like there is this insistence on making sure that Black artists do Black art. I see great artists who are phenomenal, who I admire, who are tremendously talented, and I’m wondering why they only do Black art? Is it really because that’s their passion or is it because that’s where they’re quarantined to, where they’re forced to be? I felt like early on my break with Scholastic had more to do with the fact that I was a young Black artist, illustrating a four-part book series that addressed the sport of basketball for a retired Black athlete. I think I could have pressed harder, but I also realized by visiting some of these studios that women had a very particular role. Men were oftentimes the art directors, and the women had administrative or assistant roles. That structure kind of hit me. And then, being from a poor class and trying to travel to New York, man, that was difficult. You may have experienced this; the portfolio drops back in the day before we had smartphones and iPads. You really had to go out there, track and kind of tackle some of the art directors while they were going to lunch. You had to do the work, it was hard, and I didn’t have the money for all of that. So that also limited my ability to get out there, where my living wage could be consistent.

My white male counterparts fared much better because some of them already had ties in the industry while they were in college. Connections to people who worked in studios so they could get an in-house job because their uncle was like one of those fill in animators, or their dad used to be a graphic designer. There were those relationships, and it was clear that I was not coming from that stock. I was going to have to claw my way in. My art wasn’t exceptional enough to bypass the obstacles as well. It can be deflating, you know, but thankfully, there were Black studios. The sad truth that I had to just accept was that I was primarily going to be hired by independent magazines run by Black people, which meant my pool of opportunity was a bit limited. It was very clear that it was going to be hard. You know, as a Black artist and not just that, but a Black female artist, and not just that, but a Black female artist who had no interest in heteronormative lifestyles. It’s been a rough road, but I think I’m starting to settle in creatively. I haven’t given up on finding the space that is unique for myself. I’m thankful for that. I’m also very thankful for the Black owned studios that gave me awesome opportunities to do my craft, so I’m in debt to them.

Justin + Herukhuti: From your observation, how have European/European-American artists approached Black people and communities as subjects of their art? And the Black community of Chester in particular?

Desire: There is a meme out there among animators which is absolutely hilarious. It has this Black character on Nickelodeon, which seems to always be the staple design for “the” Black character. The box haircut, you know, the t-shirt, the jeans or the shorts and the high-top sneakers. I even participated in that on one of my first projects. But they showed these four very different cartoons and somehow even though these were four different Black characters, they looked the same. It was the same design. There’s another meme out there of Charlie Brown, the Peanuts character. You have the one Black character sitting by himself while all the other characters are on the other side of the table. Oftentimes, I’ve seen Black characters used as a token to say, okay, we’re just nodding saying that you do exist, and we want to make sure one of you is there. I think that happens to a lot of minorities in America, not only Black people.

I was just talking to a group in seminary and we were discussing the issue of racial dynamics in America. And the thing that kept ringing in my mind is this thing called majority bias. My theory is that majority bias doesn’t really require you to be racist. It just requires you to live a life where you think everything is predictable. Everyone seems similar to you. They dress like you. They want the same types of music and they eat the same kinds of food. So, everything seems the same until some anomaly jumps in there and something different happens. The startled reaction that you have can be characterized as racist or characterized as insensitive. But in fact, it’s really just so out of your norm that you don’t really have an appropriate way to respond to it. At least not a rehearsed way of behaving. I think in my Americanness, I’m used to hearing a certain accent everywhere I go, and most people speak the same language as I do. When someone is not speaking the same language or has an accent, I notice it and I might ask, “Oh, where are you from? Are you, this that and a third?” Is that appropriate all the time? I don’t think so. I would like to believe that I’m not being prejudiced, racist or marginalizing someone, but I must check myself and consider how it feels for the person on the receiving end. I don’t think it’s a lot to ask for those in the majority class to do the same.

Then there’s the bias that transitions into racism, where you know better. You have these experiences, and at this point you need to get over yourself. In America, I think when it comes to the industry of illustration or animation or anything in the arts at this point, we have enough history behind us where we should know better. So why do these things still happen? There is a cultural norm that is deeply anti-Black; you just can’t get around it. American cultural identity is built on a very anti-Black foundation. You can’t get around it. Just a surface study of racial laws in America reveals this but we don’t teach our children this history. I’m thinking of the one-drop laws here. We have to address it. I think the country is struggling because it’s embarrassing, and people get defensive because it requires a restructuring of the dynamics of power and access to resources that feels threatening to the majority class. And even though these changes are not a threat, it becomes a threat regardless because it just feels different; it’s therefore a problem. This is very hard to get out of people. It’s very hard. It just is.

Justin + Herukhuti: What has the impact of white gaze been on the Black community in Chester?

Desire: I don’t think it’s necessarily specifically just about Chester per se, as much as it is about the Black community in any area of the country, dealing with a level of intimidation when it comes to the watchful eye. I’m acutely aware of when I walk or drive into a space, people will question why I’m there simply because I do not look like everyone else. Not that I’ve done anything erratic or inappropriate. It’s just, “Who are you? We don’t usually have your kind.” I’ve had those situations happen to me throughout Delaware County. It’s constant. Police stop you for no clear reason and ask you silly questions; even if they don’t ticket you, they just want you to know, “I’m watching you.” I’ve had that happen to me. My brothers even more than myself because they’re Black men. That can get exhausting. You learn how to kind of ignore that, cause you gotta survive. As a Black person in America you can just quit and decide, I’m never leaving the house. But you gotta live, you gotta make a living. You can’t let what people do in those circles, in those spaces, crush you. We don’t have a choice but to survive. It’s not a choice. It’s not that I’m being courageous. I just don’t have another option but to insist on surviving, not just staying alive but also unapologetically asserting my valid existence.

There’s also this other type of gaze that happens from the outside community looking in. And I don’t want to accuse others. I’ll just use myself as an example. I feel like as a Black person, at times, I feel pressured to make the person who’s doing the looking feel safe. You know, that I shouldn’t smile too fast, talk too assertively, look too confident. I noticed in some circles as a minority, if I’m very confident in my delivery, it could feel like people will actually try to ignore me. I’ve seen it happen before my eyes, like I’m standing in my personhood and literally I see the lights go out for them and they’ve decided they’re going to erase me maybe because they find it offensive that this Black woman would dare. You know, that has happened. I’ve had people who were good friends, white friends, who were trying to introduce me to other white people who refuse to acknowledge me by not looking at me or talking to me. I’ve had that happen. And then I’m embarrassed and they’re embarrassed. The white gaze can insist on making you invisible to invalidate you as well.

So, the white gaze in many ways can be an act of power. “I’ll see you when I feel like seeing you. And if I am looking at you, it’s because I’m watching you. Or if I am looking at you, you need to perform for me. So, I feel safe.” Folks are not always aware they are doing this until you say it to them in the moment. It can be crushing for a person when you bring to light what they just did. It takes guts to not let people get away with erasing you depending on what the power dynamics are, whether it’s your boss who’s doing it to you, or whether it’s your pastor doing it to you, versus just your neighbor, you know?

Justin + Herukhuti: How has your relationship to Chester impacted the development of your craft and practice as a maker?

Desire: So, remember when I complained about how as a Black artist in the industry of illustration, oftentimes people will try to corner you and use you as the February-only artist? My job is to only talk about Black things for Black people, only Black themes. Even Black people sometimes will look at you like you are crazy, if you’re not producing some of that. There is some level of expectation that you will have a Black awareness or consciousness in your art. Younger people, not so much. I find this to be great for them. I’m excited by how many young women are entering into art and how many of them are really good at sharing their stuff. Especially the young Black women on Instagram who are really sharing their work and are just reaping the benefits.

But to speak to your question, even though I was complaining about being pigeon-holed as a Black artist, now that’s kind of where I’m directed. That’s where I’m headed. My experiences in life have caused me to become more sensitive about the plight of Blackness in America. It is becoming a big thing in my art and I’ve actually been working on some pieces that I haven’t shared yet. It features a little girl who’s going through this world that is just absolutely bizarre. It’s kind of like a cross between Alice in Wonderland mixed with The Color Purple, my favorite movie of all time. She’s in this insane world and you don’t know how she got there. I don’t have a story for it. I just want to show her in these different environments that look beautiful if you just take a glance. But when you look much closer, you start to see all the dangers around her. That’s inspired by the work of Kara Walker. She has this beautiful silhouette style that on the surface looks like clip art. Then you look closer and you just see the violence and you see the disturbing acts that are going on. You start realizing that she’s playing on that dissonance.

One of the things that people tend to miss about Chester is the resilience of the children. Especially that they can still find joy and laugh despite all of the challenges that exist. The young adults, too, in the city are real survivors and they work hard. Like they work so hard. This stereotype of people being lazy or any of that, is just absolutely absurd. I have yet to meet one lazy person in Chester. Just the constant working, backbreaking work. Two or three jobs, minimum wage, barely making it at times. But then there’s a lot of people in the city who are doing moderately fine, oftentimes in the medical field. Quite a few Black women end up nursing and really bringing home a living wage for their family. A number of the men do city work and get hooked up with the local union as well as a lot of entrepreneurship. They’re just working and loving their family and their friends. There’s a real tight knit family connection in Chester that is admirable. It is amazing how big some of the families are in the city. That’s how you know when someone is actually from the city. Chester is a big family-focused community. I don’t think people really on the outside understand or often get that.

Justin + Herukhuti: From your perspective, what are things in Chester that art can play a role in addressing, and what are the things that art can’t play a role in addressing?

Desire: The young people have quite a few independent dance groups that play a role in building positive relationships and showcasing talent. Also, there’s quite a few people who like to do church plays that really play out in daily life. It gives people an opportunity to express themselves. There’s an LGBTQ community growing in the city. I’ve witnessed a growing LGBTQ awareness among young people, but there are more and more adults who are coming together around LGBTQ issues within the church, even. And they use things like plays and dance crews to really give positive outlets of expression to people in the city, whether they’re the one observing or the one participating. I dated a woman who was a hairstylist and watching her do that, it was very impressive. Seeing all of the different moving parts of that expression which also provides a type of self-care. Getting the hair and nails did, that’s a service to the community. People want to look good; they want to be beautiful, you know? I feel like art can address anything. So, there’s no such thing, in my mind, as art not being able to play a role in different aspects of Chester life. It will always play a role.

There’s really a lot more performing arts in the city; it’s just very performance-oriented, like theater and music. Visual arts tend to be shared through murals. When it comes to things like painting, it’s such an exclusive genre, because when people think of galleries, they think of money and wealth. But I think it is important to bring visual arts to a space where folks can see this isn’t just about the wealthy collecting art, it is also about us as a community collecting art and really supporting one another. And the truth is that art can turn into something financially beneficial down the road, if you buy it, but of course I’m going to say that as an artist.

Desire Grover (she/her) studied digital illustration & design at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. She’s been an illustrator for 18 years. She illustrated the four-book series called Hey L’il D by Bob Lanier. Over the years she has done art workshops for her community. She published her first children’s book, For the Love of Peanut Butter, and is currently working on a graphic novel called, The Fatherless Messiah.

H. “Herukhuti” Sharif Williams PhD (he/him), is the founder and chief erotics officer of the Center for Culture, Sexuality, and Spirituality. He is a playwright, stage director, documentary filmmaker, and performance artist. Dr. Herukhuti is the award-winning author of the experimental text, Conjuring Black Funk: Notes on Culture, Sexuality, and Spirituality, Volume 1 and co-editor of the Lambda Literary Award nonfiction finalist anthology and Bisexual Book Awards nonfiction and anthology winner, Recognize: The Voices of Bisexual Men. Dr. Herukhuti is a core faculty member in the BFA in socially engaged art, co-founder and core faculty member in the sexuality studies undergraduate concentration at Goddard College, and adjunct associate professor of applied theatre research in the School of Professional studies at the City University of New York.

Justin Maxon (he/him) is an award-winning visual journalist, arts educator, and aspiring social practice artist. His work takes an interdisciplinary approach that acknowledges the socio-historical context from which issues are born and incorporates multiple voices that texture stories. He seeks to understand how positionality plays out in his work as a storyteller. He has received numerous awards for his photography and video projects. He was a teaching artist in an US State Department-sponsored cultural exchange program between the United States and South Africa. He has worked on feature stories for publications such as TIME, Rolling Stone, the New Yorker, Mother Jones, and NPR.