What’s One Other Thing?

January 9, 2021

Text by Nolan Hanson with Gavilán Rayna Russom

“Part of [my approach] is a resistance to signing on to conventional norms of how things get done. It’s basically an application of a certain type of feminist music theory to a business model.”

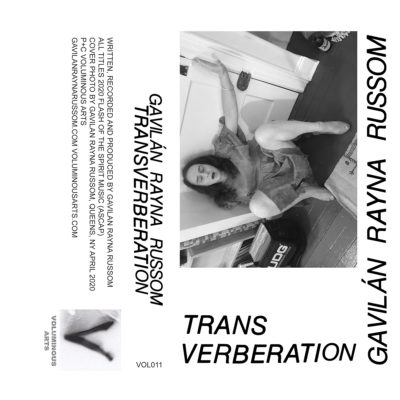

On March 9th, 2020, just eight days after the first confirmed case of the Coronavirus in New York City, people had already begun to substitute handshakes with elbow bumps. When my friend Rayna and I stood in front of The Center on 13th street and hugged each other, the gesture felt transgressive. The next day, Rayna launched her record label, Voluminous Arts. Just days after that, the city went into a period of quarantine and both Rayna and myself became infected with the virus. We’ve since talked about that hug, and both wondered if we got each other sick.

As a social practice artist, I’ve observed how other artists and institutions have responded—or, in many cases, failed to respond—to the rapidly changing social conditions imposed on our society as a result of the pandemic over the past nine months. Overwhelmingly, I’ve witnessed a lack of preparedness and a complete inability to adapt, which to me, signifies the degree to which the commercial art world has attempted to divorce itself from humanity and lived experience.

Which is why watching Rayna’s project has been so exciting to me. Rather than adopting a framework which reinscribes the values that have supported the production of creative material without regard for the humans who produce it, Voluminous Arts is a structural intervention, providing an alternative to conventional record labels, through nurturing care, conversation, and exchange.

I called Rayna on the phone to talk about her experience as an artist, and how it informs her approach to running a record label.

Nolan Hanson: You describe your label, Voluminous Arts, as a “creative support network disguised as a record label,” which I think is really interesting. I’m curious; do you see this record label as part of your art practice?

Gavilán Rayna Russom: I think a quick background sketch might be helpful. Growing up, while I was sort of aware of fine arts practices and classical music, you know, the kinds of things that become labeled as “high art,” I certainly was not introduced to contemporary art at all. But in terms of my experience of how I might be a creative person in the world, what really framed that was growing up in the punk rock and underground scenes in Providence. That was very naturally interdisciplinary—not in an academic way, but because, like in a club, you have multiple disciplines happening all at the same time. There’s dance, there’s how people dress, there’s visual art, there’s performance, there’s all these dynamics, there’s

the visual elements with fliers, album covers… And all those sorts of things exist in an interdisciplinary way and also in a polyvocal way, with multiple

people involved.

And within that was not only interdisciplinary creativity, but it also expanded beyond that, to what you might call social practice, you know, the political, spiritual, the conversational… People would publish zines, texts and we would get together and say, like, “Hey, we could start doing shows in the basement of this building.” And we’d get together and make that happen.

I just recently started to think about how that was naturally interdisciplinary, and that was how I understood a creative person could be in the world, and I just kind of operated on that model. As I started to advance in my education I encountered a very compartmentalized way of thinking about creativity, which I found to be problematic.

But at some point—along a very circuitous educational journey—I encountered this guy Benjamin Boretz, who was a music theorist. His approach was deeply theoretical and academic and he was on a sort of “unlearning trajectory.” My experiences with him were profound, and at the center was this idea of music and composition as an activity of structuring creative material over time. And that it was a thing that was absolutely inherently political. [He said] that what happens to us in a capitalist society is that our time is taken away from us, and then sold back to us and co-opted in all these ways. And the creative act can be this radical act of re-claiming agency over your time. Because if you say, “Well, I’m going to spend an hour composing,” you have, at least, the opportunity to encode meaning onto time in a way that is your own, which you can share with other people.

This idea of composition has become very expansive for me, and extends beyond writing a piece of music, and into other disciplines. The real idea was that everything that one does can be composition. The label came out of that idea, and as a result, I think about the pieces of it in an intentional way. And that’s really how I see my role—as the composer of this creative network.

Nolan: What makes your label different from a conventional record label?

Rayna: The main thing that makes Voluminous Arts a little bit different than other independent artist-run labels that I’m aware of, is that it’s very intrinsically based around my experience and particularly the ways in which working with other labels and working within the music industry was really detrimental to my creativity and also to the political impact of it.

Nolan: We live in this era where artists can operate independently, and self-release their own music. So why sign to a label?

Rayna: Because you get to talk to me, and you get the benefit from my relatively uncompromising, very carefully thought about thirty plus year career in the arts. And part of that is a resistance to signing on to conventional norms of how things get done. It’s basically an application of a certain type of feminist music theory to a business model. You know, Susan McClary talks about how there is no thing that’s like “how music goes.” You can talk about the Western tonal system, and its rules, but those rules are not this background of context. Those rules are also a composition. They have meaning; they come from somewhere, they have social resonances and political motives. So that’s the thing—it’s like looking at running a business in that way, compositionally and with intention. And again in that way It’s absolutely part of my creative practice.

Nolan: That’s really interesting in terms of the values of your label. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I don’t think practices around care and support are prioritized in the majority of record labels.

Rayna: Right, I mean, a conventional record contract says the word exploit about a hundred different times. For a conventional record label, the number one goal is to collect as many master recordings as possible and to gain creative ownership over someone else’s art, and to do that as much as possible, so that when they die, the label will be able to continue to make money from it.

And I mean, that’s not what I’m doing at all. And that’s not what Voluminous Arts is doing. So, I describe it as a creative support network disguised as a record label. And what that’s really about is creating these little pockets of care and nourishment where some really radical ideas can gestate, and then be shared in the world in a way that doesn’t negate the individual artists or artist collectives that created the work. It’s very much based on care and conversation. In a sense it flips the twenty-first century commercial model, where you have a brand, and then you seek out content that allows that brand to continue to propagate itself. Voluminous Arts is not a brand-based idea, what it’s about is facilitating a conversation that continues the process of unearthing the identity of what the thing is.

Nolan: Considering how unconventional the label is, how do you explain your approach to people who are interested in working with you?

Rayna: I think one thing has been to try to communicate as clearly as possible what the label is about, and how it’s operated. And I know we talked about this, but like one thing that was helpful for me was the shift to, you know, I started the label in March, and it was like, “Oh this is not year one, this is year zero.” And what “year zero” is about is showing people what we’re doing and modeling what we’re doing. It’s a gradual process. I’m exploring these alternative ways of doing things not for their own sake, but because I’ve analyzed structurally the way that things work in this world and I understand how problematic that is.

You know, there are these deep problematic structures in place in things that we just sort of let run freely. So I’m trying to find alternative ways to do things because I need to do that to keep my soul from turning into a charred black crumb. [Laughs] It’s not about being intentionally obscure, or capitalizing on the cachet of being avant garde—it’s really about clarifying why I’m making different choices.

That’s what’s happened in the shifting from doing my own creative work and relying on other labels or galleries to put it out in the world, to realizing that I’m interested in not only composing the creative materials, but also composing the way that those get shared with the world.

And I think you’re right [with Voluminous Arts]. There are these existing frameworks I needed to engage with, and then there are these ways in which a lot of it is built from the ground up, or bent in these ways that move it away from the sort of, default setting, towards something that operates with more intentionality and a commitment to a particular set of concerns.

Nolan: Yeah, it sounds like a lot of the process is about the framing of the work itself. You describe this “flattening” that was happening through conventional channels, where you’d make something, but then the framing of the thing—everything that’s around it, all of the context—was not actually supportive of the work.

Rayna: Yeah. And it was helpful to understand that that was very intentional, that it was very built into the structure. And in fact what was actually happening was a process with complete intention and with complete historical lineage that was actually about taking something that was creative and full of intention and communicating on a certain frequency, and flattening it into something that reinforced status quo agendas.

Once I saw that that was what was happening, I was really just disgusted and it was sort of impossible for me to just kind of keep going. You know, it’s like I saw behind the veil and it wasn’t really possible to sort of be like, okay, well I’ll forget I ever saw that and keep going. It required a total reevaluation of the whole thing.

Which is also why I started my own label. Because I understood that there was an intentional hijacking of creative materials, and a reorienting of them back towards a status quo affirming agenda, which promotes dysfunctional ideas about individuality, supports homogeneity and disregards cultural context and ancestral lineage. And I just can’t get good at pretending that’s not happening.

The whole experience and the framework of the label is based on a lot of investigation and understanding that I’ve done—so that people can come into it being able to breathe, because I’ve gone through the labor of excavating that particular flavor of bullshit. With the idea that, having done that, I can hopefully pass it on to people and maybe save them some time.

It’s also related to queer lineage—this idea that by sharing our story as queer and trans people that had a hard time coming out and didn’t start self actualizing until later in life, we can help some younger person get to that point a little earlier, and as a result, experience more freedom, less pain, and also hopefully pass it on again so eventually we reach a point where that becomes a sort of baseline of how people come into the world, with an understanding of queerness and transness…and one that is not mediated by the market.

Nolan: Right. There is one sort of way in which queer and trans people can be represented through like conventional channels or frameworks that actually just reinscribe and reinform exploitative, market driven ethics that just kind of plug new identities into it. And then there are works like Voluminous Arts, which are looking at existing platforms and actually structurally queering them and creating them from a trans perspective.

I think Voluminous Arts, and other projects like it, are doing things in alternative and interesting ways on the structural level—beyond representing something that’s different, but actually structurally embodying and supporting different values and engaging in ways that are not supported in the mainstream. I feel like the high degree of specificity is what gives your work so much depth. I find that the projects I’m most interested in are very specific; they do one thing and they do that one thing very differently than it’s ever been done before.

The autobiographical nature of Voluminous Arts is so interesting to me. You know, it’s like the materialization of things that have been pressing on you and your work for a very long time, you know. It’s like a diamond. But because it is so specific to you, it’s also very complicated. Can you speak to the complexity of your work?

Rayna: Thank you, I really appreciate that. And yeah, I think one of the biggest things in the creative arts is that, you know, if you want to be successful it has to be simple. And it’s based on this bizarre idea that people aren’t complex, or that they can’t understand complexity. It’s so patronizing and classist. You know, this idea that it has to be simple and bite-sized… I’m like, yeah, to some degree that’s true. But also I’m like, look, I’m fucking 46 years old. I haven’t died yet. Yeah, I’ve had some hard times, but I’m still fucking here. And I’m also like you know what? Fuck that shit. I actually don’t want to hear what you think I need to do to be successful. And I want to create a space where other people don’t have to hear that either, where some kid can come to me with a record and I can be like, “I really like what you’re doing, it seems like there’s part of it that you feel like you have to do because it’s what you’re supposed to do. Can we minimize that? Where can I give you permission?

Where can we make this more expansive? Where can we make this more you?” And also ask, “What would be a success to you?” And I’m like, you know, I just think about the 20th century. So many successes and successful records, successful art careers, successful victories in battle, successful inventions and you know, in a hundred years the planet was fucking decimated. Like that’s the price of that. And you know we look at those achievements, those amazing things continue to be held up to justify continuing to live the way we’re living. And that shit’s not real. It’s not real. It’s a fucking haunted weird shadow world that’s killing us. Like, now, very quickly. So, you know, what are some other things we could do, or make? Like what’s one other thing?

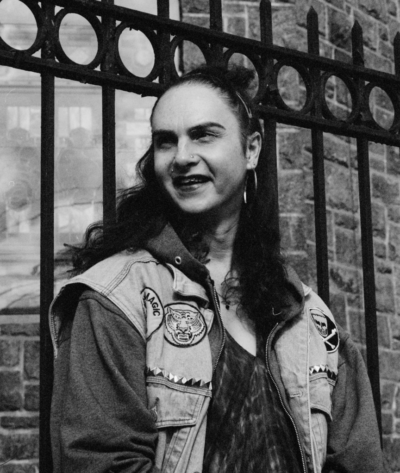

Gavilán Rayna Russom is an interdisciplinary artist based in New York City. Over the past two decades she has produced a complex and compelling body of creative output that fuses theory with expression, nightlife with academia and spirituality with everyday life. Rayna’s renowned prowess with analog and digital synthesizers as composing instruments locates itself within her larger vision of synthesis; an artistic method of weaving together highly differentiated strands of information and creative material into cogent expressive wholes. The central thread of this practice is the exploration of liminality as a healing agent, a phenomenon she has been engaged with since childhood and has researched at an astounding depth. Her work is cumulative and experiential. It requires time and attention to take in, and it powerfully rewards those who bring their time and attention to it.

Nolan Hanson is an artist based in New York City. Their practice includes independent work as well as collaborative socially engaged projects. Nolan is the founder of Trans Boxing, an art project in the form of a boxing club that centers trans and gender variant people. They are an MFA candidate in the Art and Social Practice program at Portland State University, and the 2020 Artist-in-Residence at More Art, an NYC non-profit organization that supports public art projects.