The Eyes Don’t Deny It: An Interview with my Dead Grandmother

December 5, 2023

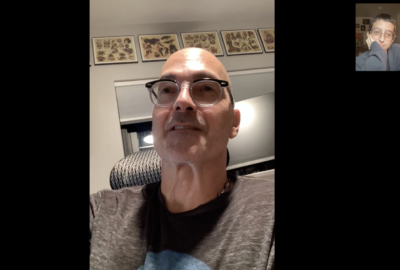

Text by Olivia DelGandio with MariAna Zachary/Michael DelGandio

– Something I think my grandmother would say

“Death would have had to drag me kicking and screaming because who the hell knows what’s waiting for you on the other end. But since I couldn’t tell my ass from my elbow, I didn’t even know it was coming for me.”

How can we blur the lines between life and death? How can we keep the memory of those we’ve loved and lost alive? How can we move past regrets and let go of the things we never got the chance to say? In an attempt to explore these questions, I decided to have a hypothetical conversation with my dead grandmother. It’s one of my biggest regrets that I didn’t ask her more about her life or have the chance to say goodbye to her.

I wanted this interview to be as close to accurate as possible so I sat down with my father, who knew my grandmother in many different contexts, to come up with her answers. I wrote down everything I wanted to ask her and, together, we talked about what we thought she might say. Once I had the interview written up, I called and read it back to him. Again, we discussed the answers and changed and tweaked until it was like we could hear her voice. Although this interview is a hypothetical, totally made up conversation I had with a dead person, it feels intensely real and I’ll treasure it as the last conversation I got to have with my grandmother and the one where I actually got the chance to tell her how much she meant to me.

Note: My grandmother, Nona, had a strong and wacky personality and I tried to capture that as best as I could but it’s hard to do someone like that justice.

Olivia DelGandio: Hi, Nonna.

MariAna Zachary (Nona): Hi, Livvie Pips.

[My grandmother used to call me Livvie Pips or Livvie Pipellina. When I asked my dad where she got that from, he said she referred to me as her little pip or pal and added -ellina, a common Italian suffix added as a form of endearment.]

Olivia: Can you tell me about your experience becoming an artist?

Nona: I always wanted to be an artist but my mother told me I had to be a secretary. It was the 50s so that was expected and I had no choice. I didn’t have the fire in me to reject it yet.

Olivia: What was your mother like?

Nona: She wasn’t a very nice lady. She used to dress me up to show me off but other than that, she didn’t care for me much. She always favored my brother and I never seemed very important to her. So, it made sense that when I wanted to be an artist, she couldn’t care less. I think I was really impacted from that lack of love even though I’d never say it.

Olivia: How’d you end up getting through that and becoming an artist?

Nona: It wasn’t until I was older and met Poppy [second husband] that I could really do what I wanted. Before that, I was a single mother to two boys with barely enough money to take care of them. I married Poppy in my 40s and he encouraged me to really start thinking about art again. So I enrolled at the Fashion Institute of Technology and I got a degree in interior design.

Olivia: I never knew you did interior design.

Nona: That’s because I did one job and realized it wasn’t my thing. I went back to FIT and got another degree in Fine Arts.

Olivia: I had no idea you had two art degrees. What did you focus on then?

Nona: I painted a lot and I really devoted myself to textiles. I made a lot of scarves and sarongs with silk screening, dying, and batik processes. Your dad would take them to work and sell them to all the girls in his office for me.

Olivia: That’s so cool. What’d you do once you graduated?

Nona: I got a job as a teaching assistant at FIT and I did that up until we moved to Florida to be closer to you guys. I loved being near you and your brothers but that move really fucked with me. I’m a New Yorker, Florida wasn’t the right place for me. I missed the city and FIT and having my own practice. My work was never the same.

Olivia: I never would’ve known you felt that way. I loved working in the studio you made in your Florida house, it seemed like everything was so great but I guess I was too young to know otherwise. Did you ever make work about those feelings or other emotions?

Nona: No, I could never go there. I’ve been too traumatized; there’s a lot you don’t know about my life and that’s how I wanted it. If I went there, I don’t think I’d ever come back. Even though I never talked or made work about it, I feel a lot. It’s the darkness in me. And the Scorpio energy. You get that from me.

Olivia: I seem to have gotten a lot from you.

Nona: Those eyes don’t deny it, you look just like me.

Olivia: You know, the only time I’ve ever seen you make anything emotional was when you were living with us when I was in high school. You were already pretty deep into Alzheimer’s and I got you to come and draw with me. You did a self portrait with something written on it about feeling lost. I felt so emotional watching you do that. There was so much I wanted to talk to you about but we had already been losing you for years at that point.

Nona: I guess my memory was so gone, I forgot about my rule of not being emotional in my work.

Olivia: I wish we could make something together. What do you think we would make if we could?

Nona: I wish we could, too. I think we would do some sort of self portrait project together. It’d be really dramatic and beautiful.

Olivia: I agree. You are the one who got me into photography. I still use the camera you got me over 10 years ago and I think of you every time I do.

Nona: I’m glad. The second you picked up mine I knew I had to get you your own.

Olivia: Nonna, what was it like to lose your memory?

Nona: Honestly, I was scared shitless. I’d come downstairs and stand in the kitchen for ages, having no idea what I was doing there until your father would come in and offer me something to eat or drink. I knew something was wrong for a long time but those last two or so years were the worst. I didn’t even recognize your father the last time I saw him.

Olivia: Were you afraid to die?

Nona: I think if I had my wits about me I would have been. Death would have had to drag me kicking and screaming because who the hell knows what’s waiting for you on the other end. But since I couldn’t tell my ass from my elbow, I didn’t even know it was coming for me.

Olivia: What do you think of what I’ve done with my life in the past few years?

Nona: Oh, I’m beyond proud. I’m your biggest fan. You know, it sucks for everyone that I’m gone but I think it especially sucks for you. We always had a deeper connection; I saw so much of myself in you. I regret that I really started losing myself when you really started to find yourself.

Olivia: But you helped me find myself long before that. Some of my favorite memories are of you taking me to get coffee (that I wasn’t allowed to drink) and we’d wander around the art supply store for hours together. You’d buy me whatever I wanted and then let me make a mess with it in your studio. I wouldn’t be the artist I am today without you. I regret being gone for the last year of your life but I am glad to have these memories with you. And especially glad that the last time I saw you, you still had enough left in you to know who I was.

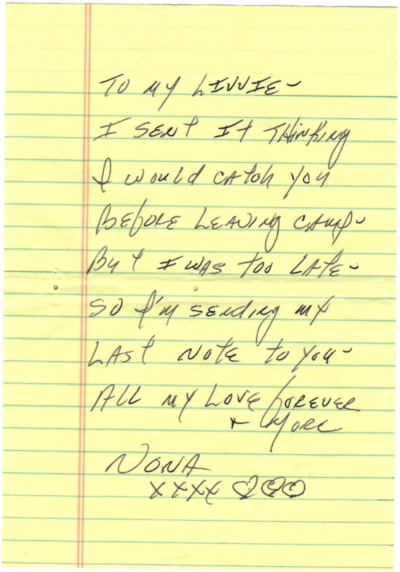

Nona: I never could have forgotten you, my Livvie Pipellina.

Olivia DelGandio asks intimate questions and normalizes answers in the form of ongoing conversations. They explore grief, memory, and human connection and look for ways of memorializing moments and relationships. Through their work, they hope to make the world a more tender place and aim to do so by creating books, videos, and textiles that capture personal narratives. She is MariAna’s granddaughter and is the artist she is because of it.

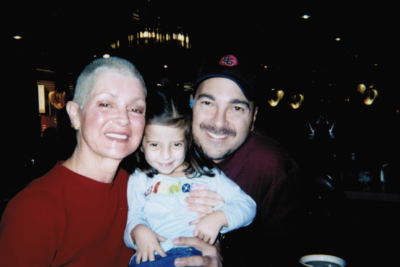

MariAna Zachary (1944-2021) was a painter, photographer, and textile artist from Brooklyn, New York. She liked her grandchildren more than anyone else, smoked a lot of cigarettes, and had two degrees from the Fashion Institute of Technology. She was Olivia’s grandmother and is missed every day.