Tobacco, Time, and Tarot: Connections to Youth Partnership

June 2, 2022

Text by Lillyanne Phạm with ridhi d'cruz and Jackie Santa Lucia

“We can do cool sh*t all the time, but I just feel like we have limited finite moments together to share and really grow together. I’m going to those rituals. People are sacred and our lives are sacred. The time that we spend together is sacred.”

ridhi d’cruz

My SoFA Journal interviews have been spaces for me to materialize a letting go of institutionalized and organizational conflict. I’ve had the privilege to be in academia for five years in a row and employed in non-white, non-cis male dominated spaces. At the same time, I’ve had to navigate intensely sticky conflict that pulled out a lot of my childhood and survivor traumas. This led me to tackle various dimensions of youth of color organizing as a means to reach out to other seedlings with a,You are not alone.

As I dove deeper into Portland, Oregon youth of color organizing, I met and worked with Jackie Santa Lucia in the Spring of 2020. She gave me the tools and mentorship to build the foundation for my teens of color focused program, Youth for Parkrose, with Historic Parkrose. Then I finally and formally met ridhi d’cruz as an organizational partner, a workspace colleague, a comrade, and a plantcestor doula. ridhi, Jackie, and I worked closely together at the beginning of this year as Your Street Your Voice instructors, a program founded by Jackie. We also shared a journey of discomfort and burnout. In this, we had many hour-long conversations around the meaning of being youth-centered and the Portland activist industrial complex. Below is a glimpse of our friendship, our mentorships, and our youth partnerships.

🍃Tobacco🌱

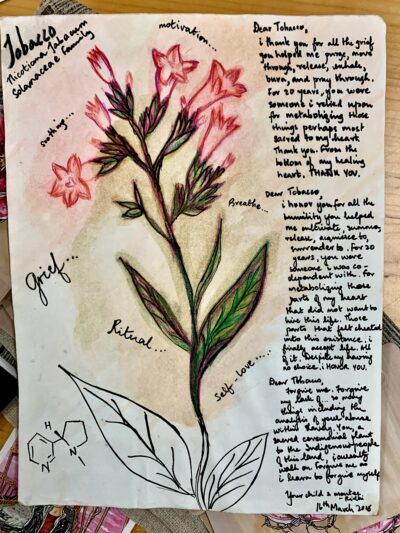

Jackie Santa Lucia: Is that a tobacco flower?

Lillyanne Phạm (LP): Oh! I saw that earlier and I loved the letters you wrote on it. Do you want to talk more about it?

ridhi d’cruz: Tobacco helped me get through some tough times in my youth. I didn’t have mentorship. More than mentorship, I didn’t have a deep connection which, for me, is how I would imagine mentorship: somebody just being with me. I smoked tobacco for more than half of my life, until I was 35 and I started when I was around 14. It was only until I came to this land, I found out about tobacco being used ceremonially and the legacy of slavery with tobacco. Then I worked with a tobacco plant, grew it, and got to know more facets of this plant. It was more than in a pouch. I got to know it in my own way, connecting to a very sacred plant.

So, I try to soften that self-judgment. I feel like whole new dimensions of tobacco opened up to me. I was able to answer what was driving me to use it in this way. I was like, “I am ready to transform my relationship with you.” I haven’t smoked in five years. It was hard. I have had a couple of drags, but I would be like, danger! Okay no. I think this plant is so incredibly powerful, and sacred, and helped me deal with my grief. So, when I had other coping skills, connections, and ways to deal with grief, my reliance on that way of working with tobacco felt released. I do this [holds the illustration] as an ode to tobacco because I continue to learn so much and feel so much about this plant. It’s a testament to how powerful the plant can be. So many people in the world are gripped by tobacco in a way. I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad thing. I just think tobacco is hardcore.

Lillyanne: This reminds me of how you teach about blackberry bushes. Words like ‘invasive’ are used to describe it, but it can be repurposed in various generative ways. You bring more awareness to dismantling the good/bad dichotomy with plants. I used to smoke tobacco for years and it increased when I first left home. It made me feel like I had something. I could sit and sleep in my car if I had cigarettes. I could self-isolate in college if I had cigarettes. Then I stopped because I smoked like five packs a week and felt disgusting. I never mentioned that I used to smoke because it’s very stigmatized. I feel ugly and gross. I feel like people think my teeth are yellow and my nails smell. After hearing your story about smoking and working with tobacco, it makes me want to mend my relationship with it. It’s funny how you mention that it’s kind of like a mentor. I think it can definitely lead to over-mentoring.

ridhi: I think capitalism and colonization have contributed to cheapening it. Cheap is not necessarily bad, but making it so accessible. Certain plants are not meant for that. It’s about dose. When it’s like an intense plant, we should hang out like once a month or something. It’s not an everyday plant.

I love that you talk about connections because that’s what drew me to tobacco. I felt comforted. It didn’t matter if other people smoked with me or not, especially in those times when I didn’t have anybody else. Tobacco was a friend, which is the experience of a lot of people. I think about the plant and I’m like, If you ask anybody who smokes this plant if they have a plant connection, they’re not going to think of tobacco. This plant’s ability to reach is incredible. But, we demonize it. Yeah, you’re not supposed to consume it in a particulate way. At the same time, we’re not supposed to be living in this oppressive f*cked-up society. So, we do what we can and need to do to get fu*king through it.

I think tobacco has specific medicinal properties. And what I’ll also say about mentorship—it’s giving and taking, consent and reciprocity. The more that I get to know plants and people, the more I understand the specific medicine that each individual has to offer. From plant to plant, they might differ. From person to person, it might differ. Deepening that relationship helps me understand like, Whoa, Where am I? What am I feeling? Oh, I just need ‘this thing.’ I don’t want to stigmatize tobacco because we are holding a lot.

I’m trying to be grounded in my own being. So that when I approach another entity, I do so from my own sovereignty. I’m not grasping for, putting expectations on, feeling a lack of, or co-depending on “this thing” to fill something within me. The more I can live into my own liberation, the more I can actually use Thích Nhất Hạnh’s concept of being into being. To tobacco, I can say, “You are an autonomous plant and strong being.” Then I can say, “I am a being too. What’s here?” I come with openness rather than “I’m stressed out and I need to smoke.” With that said, there are so many things that I survived and tobacco definitely brought it back to me.

Jackie: My first cigarette was when I was 13. With the coming of age thing I thought I was so cool and an adult. I thought, now, I can hang out with older people. I can handle this. And, talking about mentorship, I think you were saying that even as a 13-year-old person we hold beings. I was a whole person. I didn’t feel that way at all. Tying it back to the young people that we spend time with, me being an older person in relationship with them, I see them as whole human people. They might not see themselves that way. I’m also thinking that we rely on and we seek relationships with things like seeking approval and smoking a cigarette.

If you asked me about my relationship with plants, as a 17-year-old, I would say that I don’t have one. And it’s like, okay, you’ve got a pack of cigarettes in your car. Do you drink coffee? tea? Yeah. You eat fruits. And I’m drawn to specific things because it evokes memories and comfort and I feel better. And it builds connection. I want to think a little bit about plants in terms of connection and youngness.

ridhi: If I can bounce off that a little bit and say part of the medicine of tobacco is ceremony. I think in this time and culture most of us are really craving ceremony and craving like the markings of passing through different life stages. Most cultures mark those times. Over here, it’s a driver’s license and random bureaucratic sh*t. We don’t have a way of tuning the human to be like, you are a full being. My teenage years were one of the hardest transitions I’ve ever had, with puberty hitting, sexism, and patriarchy really falling on my nonbinary body, and me not having the vocabulary to describe my experiences. So, tobacco was really important to me because it helped me be like, I’m tough. I got all these things.

Jackie: Protection.

Lillyanne: Yes, you can easily leave the room and no one would bother you.

ridhi: There are so many ways to self-care. Even though people are like, Oh, your lungs have been destroyed. Our self-care in our own autonomy is just under the surface of a tobacco practice.

⌛Time⏳

Lillyanne: Since investing more time into plants, I’ve seen myself forgive myself a lot. I’ve also learned a lot from the youth I work with about their openness to accept the expansiveness of plants. When I was younger, I was very hard on myself because I grew up with a lot of no’s and restrictions. Now, I’ve been given the freedom to reflect on complexities because the people and plants around me say, be gentle with yourself. You deserve it. Healing my inner child by working with plants has softened my outer child. I can break things. I can be messy. I can experiment. By talking about smoking through centering the plant, I think I am more open to saying I smoked. There’s so much shame that happens with time/age. I think it piles on top of each other. If you don’t have a community to talk to, it just stays there, which is kind of scary.

Jackie: That brings up a big point in terms of what you shed light on and what you don’t, and where the safety is for that. As a young person talking to older people, I would have never told anybody that at all. I would have needed to have time pass to share the shame. The young people that we spend time with, I don’t see that much shame. I’m sure they have it. I’m sure they sit with it. But they share it. I think that’s something that I really admire. And I learn a lot from them too. When both of you were mentioning not having the language and how the binary can’t hold our entire world from plants to gender, I have enjoyed being able to unlearn that way of thinking. And live and experience life not being in binary with multiple age groups, too.

ridhi: I’ll add to that and pick up a thread from LP. As a young person, I felt this pressure that being an adult meant being perfect. And there wasn’t a supportive culture around failure. I think there’s a window when you’re really really young and you fall on your face and it’s whatever. But, I think there’s a bigger period, especially in your teens, where people are dismissive, derogatory, and ageist. When you become an adult, you’re like, None of y’all frickin’ know what y’all are doing. This makes even less sense to me.

I also remembered feeling very betrayed because I grew up with very binary thinking: right or wrong. So, that was my projection of the world for a bit. You do good, then good things happen. I feel like that was the protectionism of sanitizing childhood for some folks because I grew up with class privilege. My parents buffered me with love. I get that. I also feel like my teenage years were like, Why is this happening? What is this caste system? Oh, this is fu*ked up. I didn’t choose this. I feel like that was part of the grief. It was very hard for me to accept this life. You have to try to get some weird career. I was like, “I opt out!” Then there’s no other option.

I appreciated that my dad took the time to talk to me and work out problems with me when I was younger. There were very few adults who would look me in the eye and say, “Yeah, you’re right. This sh*t that we made up is bullsh*t. Your fresh eyes, questioning, and critical thinking are welcomed here.” Instead, people were really defensive and mirrored it back on me. So, the elders that I really appreciated are the ones who are humble and acknowledge that we grow and learn together. We just have different positionality based on our experiences. Someone can live 70 years and not have wisdom. I call them olders versus elders. You don’t get to self-prescribe that you’re an elder. People call you an elder because you are an elder to them. You can be an elder who is young. I’ve had those types of people in my life. I’m just like, Oh, you’re an old spirit or You’ve been around this block.

The mentors that I really appreciated have been the ones who would receive mentorship from me. In India, there’s a lot of age hierarchy. And that inner child, they never let die. They are always learning. Of course, they make mistakes like pronouns. I’m not saying they’re perfect. But their commitment to continue to learn and be shaped by others showed me what an elder means to me. With people who are younger than me, that’s what I hope I convey. Just because you’re younger doesn’t mean you’re less. It also doesn’t mean you’re more. We’re just different. And I have as much to learn from them. We’re here to learn and grow with each other. Hopefully, we get to impact each other and our healing.

Lillyanne: I can’t believe that I haven’t asked how y’all got into youth work! I loved how you mentioned your dad giving you the time and space to figure stuff out. Did your dad shape your youth allyship work? Also, Jackie, has your mom shaped yours? You mentioned before the interview about your mom coming into the elder role.

Jackie: My mom is definitely a big influence on my relationship with young people. My mom is a nurse. She also was raising three children basically by herself. She needed to get a job. So, she was a camp director for years. Always, there was the connection to being outside and being with all different ages and taking care of each other. And having fun with nature. So, that’s one piece. It’s interesting that you’re asking this question because I didn’t make this connection until Your Street Your Voice started.

My background is I’m an architect and studied architecture at Syracuse until 2008. Then I moved to New York City. I was working by Wall Street when the first crash happened. I got laid off. I was 23 years old. Afterward, I started freelancing and substitute teaching for a French class in New York City and New Jersey. I was on extended substitute teaching. You can only watch so many French movies and musicals. So, I ended up doing design workshops with high school kids in the middle of class. And I was like, “If you could change this room, how would you? Would you want your furniture to be in here? Or do you want to draw something on the whiteboard? We would just do these random things every day.

Flash forward, I moved to Philly and went to graduate school for architecture and immersive kinematic robotic design. I started working at this incredible magnet high school called the Sustainability Workshop School. It’s all project-based learning. It was started by a mechanical engineer Simon Hauger, but he was also an automotive vocational teacher. At this time, West Philadelphia High School was about to be condemned. Instead of teaching his students how to fix diesel engines, they designed and built electric cars. They competed against major companies like Ferrari and Ford and won all this stuff—enough to build their own school. So, they took over the school. All of the projects are based on sustainability, climate action, and working directly with industry, and I got hooked up with them as soon as I graduated from Penn.

.

Here, I became a mentor through Philly’s Project Graduation mentorship program. This was 2009/2010 and the graduation rate for Philly high school students was like 40% and, for BIPOC students: like 25%. So, you have a freshman mentee and you are with them until graduation. My mentee’s name is Nicole at the Sustainability Workshop School. Long story short, I got involved in a lot of awesome projects there. We did a living container, living garden, greenhouse with solar panels, and a full green roof. Students were doing a whole living irrigation system and using plants to do culinary stuff. I helped them set up their digital fabrication lab too. Just fun, fun, fun, stuff!

After graduate school, as an architect, I had the privilege to work on these projects called American Spaces, which were basically study abroad programs using the Smithsonian collections in partner countries with their consulates around the world. I was able to travel to multiple continents and worked with many young people. The constant was, Design can change people’s lives. If you have your own agency and choice in how you impact your environment, and how you do that across language, across age, across culture, across all of it — it always takes time, takes trust, takes fun, and takes joy.

So, that wrapped up and I moved out to Portland and had a complete culture shock, such as the lack of a design community. I should have realized that piece of my career, working in the community, working with young people, and actually physically making stuff, was something that I really needed and enjoyed. So, when I came here to work at a renowned firm that does culture work, they had no contact with young people and communities of color. So, I convinced the firm to sponsor the creation of a program similar to the Workshop School. Students would be paid to participate and think about design issues. And that’s how Your Street Your Voice started.

Do you want me to get into the whole Your Street Your Voice thing? [Everyone laughs]

Basically, we came up with the idea of this question, If you could change one thing in your neighborhood through design, what would it be? And we asked any young person while centering Black and Brown youth, ages 14 to 20. They had eight weeks to come up with some ideas, using the model of a design studio, and a design process of building something in place. This was six years ago.

Lillyanne: Wow, you basically started Your Street Your Voice when you were my age. You started it as a substitute teacher holding space for teens to design and play.

Jackie: I never thought about it that way.

Lillyanne: You were growing through this too. You were 23, technically a youth too. How did that work?

Jackie: That’s so interesting. When I graduated college, I thought I was grown. I was living in New York City and had roommates. I felt like I was grown. Clearly I wasn’t, even though I felt that way. It was only in the past five years that I’ve felt a major age difference between the youth that I work with. But, I’ve always felt that working with young people is also growing with them.

Lillyanne: I didn’t consider myself a youth until I graduated undergrad and worked with older folks. I’d apply for jobs and they’d require me to be 25. Then I found out that 25 is when the brain develops out of adolescence. I also noticed that at my various workspaces I was always the only or one of the few youngest people in the space. For example, when I co-facilitated a Your Street Your Voice workshop, one of the guest instructors thought I was another high schooler. I joked and said I was a freshman. And he believed me. I face a lot of ageism. People automatically think that I don’t have much life experience or make sweeping statements about my abilities. Older folks around me become very guarded or feel like my success is due to my exposure to their skills. I wouldn’t call myself a youth unless I’m directly addressing youth justice and ageism in a space. I’m fully aware that I’m a young adult on my own journey through age. But, I’m also a 24-year-old who is constantly being mistaken for a high schooler, inexperienced, going too fast, and being too naive.

ridhi: Can I add a layer to that? I also feel like it’s ageism combined with sexism and racism specifically the way that Asian folks are infantilized. It’s a form of colonization. I came to the U.S. during my Saturn return at 28. People would treat me like a kid. It’s one of many ways of dominance over young and women presenting folks.

Lillyanne: I think the opposite goes for Black Asians and Black and Brown non-Asian young folks who are forced to go through adultification. Those in power treat them as children and adults when they want to strip power and knowledge from them. They’re too young to drive or have a credit card. But they are old enough to be punished for missing school or being too hungry to focus on an exam. They give them a cruel and purposely oppressive amount of responsibility to prevent their ability to thrive and survive. I especially think about how the city and huge funder organizations want to work with low-income youth of color but aren’t willing to pay them a living wage for their labor.

ridhi: For me, there’s a power dynamic; young people can’t drive. If we go back to consent, if they’re in a power dynamic with a caregiver or someone that they’re dependent on, then there’s your power dynamic. That’s where I feel like we have to pay specific attention. So, we avoid calling something consent when we actually don’t know due to the power differences. We apply this rule between adults from different positions, so I think the same goes for young people. I’m still learning in all the different ways. With young people, I’m like, You feel disempowered in these ways because of your positionality; therefore, as someone with these types of privileges, I need to be more responsible and wield the powers and privileges that come with being an adult.

Jackie: I think that’s a really good point, ridhi. In terms of power, it is such a throughline. I would like to add the building of that intersectionality of power with racism, classism, sexism, capitalism, and also industry. My youth engagement has always been in tandem with the industry of architecture in the built environment. And that is steeped in power internally as organizations with people, steeped in power over land, over dominance, over extraction of materiality. This is often true more times than not.

Something that I’m sitting with a lot is I think that there is a wave. I think that there is a genuine interest in having community-centered design and community-led decision-making. But, I think it definitely falls short. It doesn’t meet the bottom line of making the budget or making the timeline. So, going back to what you were just saying in terms of the tokenism piece of our young people, how do we create meaningful engagement? Or how can we foster and follow young people’s lead and the engagement that they want to be part of?

The “power over” piece is such a big deal. I think in the sense that I want to hold back and follow our young people’s lead. When we talk about power with young people, I’m thinking of myself as a young person, and I didn’t understand the type of power that I actually had as a young person. You can’t even have a bank account without your parents signing it. You can’t get a credit card without all of this stuff. You can’t get your own apartment without your parent co-signing or at all. You can’t get your basic needs.

ridhi: It’s gatekeeping. I’ve been really sitting with the age segregation that happens. I get that there are certain things that happen at certain ages. And it’s fascinating, biologically, physiologically, cognitively—there’s some stuff. But I also feel with intersectionality, that pluralism, and being in a multigenerational space is a very basic, age-old way. I feel like part of what colonization, capitalism, sexism, the patriarchy, and all these ‘isms’ have done is segregated us by age.

For me, coming from India, I remember feeling like y’all made me hang out with just my age group. So, I sought elders. I sought that diversity to enrich my own learning experience. As I see modernity progressing, age segregation intensifies. I feel like multigenerational is not just letting one person or one group lead. It is, I want to be with you.

I’ve heard a really beautiful saying from some mentors in the housing justice movement: Nothing for us without us. As a brown settler, newcomer, and guest doing indigenous solidarity work, I have this thing where I feel that others should go in front. But I heard something really beautiful from an indigenous friend who reminded me, “You do not walk in front of us. But you also do not walk behind us. We walk together.” That visceral image stuck with me.

Lillyanne: With racial justice organizing, I’ve heard something similar like moving from an ally to a partner. Instead of waiting for orders on what to do, you know how to step in and collaborate because you’ve built that relationship and trust. How have you all created youth workshops in collaboration with the youth? There is giving a prompt and having their response, but, how can they own and experiment with the creative direction of a co-learning space in a container that you facilitate?

Jackie: It’s an unfolding and iterative process to figure it out. Like from the beginning, I think a lot of facilitation is asking a lot of reflective questions. One of our exercises that I love is the five senses of how you experience space. Oftentimes, we experience space with our whole body. Identifying five things you smell is just very objective. Then put some emotion to it. What does this make you feel? Why do you like this window? Once you get through the five senses, you get to the root of something interesting or something that’s super true to an individual young person.

I think specifically with the community looking at projects in neighborhoods and communities. They live and breathe that space and those plants in that land. Everyone has an inner knowing of what brings them joy and happiness. I say that with the preface that oftentimes, especially with BIPOC communities, having these questions of what is a joy to you can be very challenging especially when basic needs are not being met and if you’re in constant survivor mode. We have a lot of young people that experience survivor mode since they are born. And being asked something like, “Do you like this chair?” Their thoughts would be, “I can’t even think about this chair because I’m worried about being able to feed my family dinner tonight.” Those are really heavy things.

In terms of my experience with co-creation, safety has to be established first. It can be as simple as, “In this room with the three of us, you gave us delicious food. We know that this space feels safe. There are doors. I know of exit places if anything happens. We can put our shoulders down for a little bit.” I think if that doesn’t happen then it’s tough to get to the collaboration piece. Once you have established safety and the different types of accommodations for folks, I think having everyone feel like they can make their own spot is just the start of the collaboration.

Lillyanne: My next question is how Youth Power PDX (YPP) worked as not a nonprofit. How do you meet the needs of your youth? How does its unknown longevity feel? It goes because the people love it. I’m curious about the magic that happens.

ridhi: It’s the young people who we recruit. It’s Andre who’s one of the organizers. Andre is a trusted person who has established safety with young people. I’ve been building some youth networks. It’s word of mouth. I feel like in today’s world you can’t trust stuff at face value. It looks great on social media. Yes, all of the language is there. But, it’s not working. It’s not about the what or even the why. It’s the how. How are we doing this together?

Back to the young people. They do amazing stuff. They bring their community who think YPP is cool and get involved the next year. There’s always been a connection point and overlap. Also, it’s about trust and respect. When I watched both of y’all as facilitators, I witnessed a lot of respect, deep listening, and reflection. Often people view young people as incomplete. We don’t actually respect and see people for the fullness that they are.

When you create a space where you say that we care, and not just this one time and this one way. I’m actually going to make you suffer through learning how to do a spreadsheet and looking at the budget because I value your opinion and how we are collaboratively making the decision to spend money, including how much is coming to you. We peel back the layers. It’s scary and boring stuff. But, we are meeting each other where each of us is at. Sometimes young people are obviously like no; however, the invitation for you to make this decision is always there.

YPP is not a nonprofit because then we don’t have the overhead stuff. And I feel like putting that on young people would feel funky to me. That’s adultification where this starts to feel exploitative, where we’re not giving like living wages, we’re not giving benefits. I wouldn’t do that to a young person. Also, we have a little more flexibility and we are more responsive. And there’s not as much to lose.

There’s so much on this testing culture, this one moment. I feel like being able to say, “We can make this whatever we want” blows people’s minds. They’re like, “You’re not going to be upset with me if I said I would do like 650 things and I could only do two?” I’m like, “No!” And I think that’s a profound moment of healing. Where we all get to heal together. This is still an incredible event and let’s enjoy it.

Lillyanne: Let’s have a conversation. Let’s make a meal. Let’s go for a walk. You’re talking about relational work. People are always like, “We’re trying to move from transactional to relational.” But, do they know what that means? Are you willing to tear systems down for this relationship?

ridhi: Sometimes I get goal-oriented and forget to enjoy the process of making. Then a younger person who is volunteering ghosts me. I would call them consistently for two months and leave messages. I’m worried about their well-being and not their tasks. They would be like, “No one’s ever done this.” I feel like, what’s the point if we’re doing some event? We’re here today. I think being together, in community, and building relationships. That’s the point for me. The rest is like a great byproduct. We can do cool sh*t all the time, but I just feel like we have limited finite moments together to share and really grow together. I’m going to those rituals. People are sacred and our lives are sacred. The time that we spend together is sacred.

Jackie: When you were talking about the shift of expectations of building this collaboration together, I think that’s something that I love, is how we’ve collaborated together. We thought it was going to be this way, but it is definitely going another way. And it’s gonna go another way, and another. We’re gonna take a break, and we’ll come back later. If we don’t collaborate as a team again now, the timing will reveal itself.

🔮Tarot🕯

Lillyanne: We’ve had our own ceremonies throughout this time we’ve known each other. How has this container been for you all? We all have our separate lives. We all have different circles in Portland too. Coming to Alder Commons and being in ceremony together, how’s it making you all feel?

Jackie: I love it. I’m grateful. I love the inter webbings of things. I think it makes me feel connected to the extensions of you all.

ridhi: I love it so much too. There are reasons people find each other. Even in the short time that we’ve known each other, the depth at which we’ve connected feels significant. While there are a lot of nuances and differences in each one of us, I see very similar commitments to certain things. There’s going to be collaboration in a variety of ways as time moves on because it just feels like it. This is what community feels like. It’s hard to put into words. But there’s a knowing. When I peel back, I’m invested in y’all’s trajectories. Even during this one-hour conversation, I’m like, Wow, there are so many insights I’m having and closures and expansions and so much is happening in my body. Because I’m with two people that I feel like we’re on soul journeys that are being created together for a purpose.

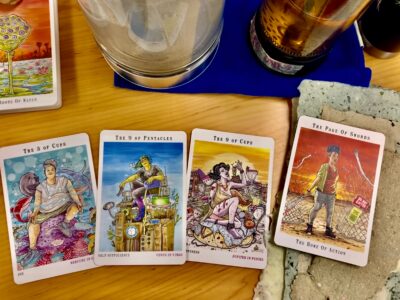

Lillyanne: Okay, let’s do this. Let’s pick a new card, leave the card from the beginning of the interview, and shuffle. Let’s think of the question, “What is your relationship to time at this moment?”

Jackie: This is interesting. It’s the same card.

Lillyanne: You picked the same card! I shuffled pretty well. That is very weird. How about you go first in reading about your card.

Jackie: The Page of Swords cuts through the walls that divide us from privatized natural resources. She rallies other warriors: other purveyors of safety and truth, teachers, activists, and youth. She laughs when seen as a monster in the eyes of industry, environmental terrorists, and white supremacists. She rallies the court of Swords as her affinity group; together ensuring a radical array of ancestral gifts in the frontline of any revolution. The Page of Swords asks you to cut through the roles that are forced onto you. She asks you to speak your highest truth, fight your greatest fight, scam your greatest enemy, and rage with your fullest heart. Whose side are you on? (Description by Cristy C. Roads)

Lillyanne: Wow, how does this sit with you?

Jackie: I’m feeling tingly? Because this definitely sums up the conversation that we’ve been having and cutting through binary thinking of age and time.

Lillyanne: ridhi, would you like to go now?

ridhi: Sitting on top of a sanctuary of her own doing, the 9 of Pentacles lives and breathes self-sufficiency. Her sanctuary includes vessels for her creative tools, self-care tools, fair trade coffee, out-of-print vinyl records, and a do-it-yourself sound system made entirely by herself. The 9 of Pentacles reminds you that you are capable of this. After diligence, determination, editing, and self-checking; comes pride, honor, and whimsical completion. The 9 of Pentacles asks you to own your Work, define your privileges, and slowly combine them in order to practice the kind of self-sufficiency that results in patience and generosity. (Description by Cristy C. Roads)

For me, the throughline is that I want to be the mentor that sees the wholeness and holiness in other people. And who lives that? And is that myself? Self-sufficiency can be a mind trick. It doesn’t mean living on an island. It’s that sovereignty. When I am seated in my own power and trusting myself and my own birthright to belong, that’s when I can live in liberatory relationships with other people.

Lillyanne: I’ve always felt like relationships complete you in some sort of way and they help you be more you. It’s not about taking from each other. Like you’ve said Jackie, you get to experience life together and mold each other.

ridhi: I’m also curious about the other card that I pulled at the beginning. I was trying to find it because I thought it felt visually gentle and I’m not used to gentle. But you go first LP, while I find it.

Lillyanne: Basking in an endless array of home brew, sparkling sheets, and jewels—the 9 of Cups reminds us to stay glamorous. She reminds us of the glitter that accented our darkest nights, and the lights at the ends of every harrowing tunnel. The 9 of Cups is a stellar machine, working hard to survive independently, and allowing herself to indulge in the luxuries that she only dreamt of before this time. The 9 of Cups asks you to rage and bloom as she directs you towards your sanctuary, your day spa, your sexual fantasy—your retreat from normalcy. She asks you to luxuriate but she asks you to stay present, as this moment defines much more than a good time. Are you honoring your gift? Are you revealing at the expense of others? Are you dedicated to the cause that brought you here? The 9 of Cups reminds us of the revolutionary role of self-care. (Description by Cristy C. Roads)

After our conversation today, I feel like I can close up a lot of the conflict that has happened to me in the past few months at the hands of institutions and community organizations. As ridhi mentioned before the interview, I’m saying no. And a no is a yes—to myself. This is the ceremony that I needed. And I’m grateful for you all. When I was hearing everyone’s cards, I felt like they were connected which felt very meaningful too. Anyways, ridhi, I would love it if you read your original card.

ridhi: The 3 of Cups is a party on another planet where you are at your wildest, and your safest. The 3 of Cups trusts their interspecies community–they trust nature and the law of respect. When you listen to your surroundings, your surroundings know you care. The 3 of Cups is a get together unlike any other, as laughter and discovery overpowers escapism. The 3 of Cups asks you to discover magical pockets of joy and camaraderie, and revel in your new definition of safety. The 3 of Cups doesn’t need to discuss or reiterate—they want you to jump and laugh. They ask you to reconnect with your happiest, safe haven and find peace in chaos. (Description by Cristy C. Roads)

Jackie: Oh!

Lillyanne: That’s so weird that that was the first card you chose after we warmed up the room before the interview with a conversation about our life updates. That was the vibe.

Jackie: Yes! You talked about the party and plants and…

ridhi: Interspecies! [We laugh] The party is for everyone! I love it. It’s been such an intense time and things still feel intense in many ways. But I’m tapping into something that feels just so benign, benevolent, soft, timeless. I feel like we use the word intuition, and it still feels individualized and out of context for me. There’s an intuition or a knowing and it’s like a déjà vu, this has never happened before. More recently, I’ve just been like, Oh, that’s because I’m feeling my ancestors. I’ve been shaped by them and there’s something familiar. Familiar comes from the root word familial, right, and intuition is not something about my progress. I’m literally the current version of my ancestors. It feels so much more guided and grounded. I can trust this journey because I’m still struggling. And I don’t want to be individuated or separated. This is for us.

ridhi d’cruz (they/them) is a gender queer Malayali who grew up in the city of Bangalore in southern India and moved to Wapato Valley (Portland) in 2010. they fondly identify as a facilitator, artist and peer mentor. they locate the roots of their life artistry in the intersections of place, healing, design and creative justice(s). they have dedicated over a decade of their life to designing community processes that cultivate liberatory and healing senses of place. they know firsthand the deep healing they experience belonging to themselves, to each other and to the more-than-human world. they believe this is especially true for folx inhabiting intersectional and targeted identities of race, gender, class, ability and more. As their anti-oppression practice deepens, so does their reliance on plant medicine. Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and Queer and Trans (QTBIPOC) folx, endure, survive and transform the ongoing trauma of white supremacy culture, colonization and capitalism. they believe that we need revolutionary acts of self and community care. Centering their own well-being has been and continues to be one of the most challenging and yet transformative practices, helping them decolonize their life artistry and place justice practice. they believe that we all have a birthright to belong. To be well. To reclaim our ancestral lifeways and to experience radical forms of care and support. they strive to honor and benefit the sacred and stolen lands of the Chinook people and several other tribes both recognized and unrecognized that they are a guest upon. you can follow them on IG @ridhidcruz and email them at ridhidcruz@gmail.com.

Jackie Santa Lucia, (she/her) AIA, LEED AP is the co-founder and program director of Your Street Your Voice and EmpowHER. Jackie is an architect and educator, with a focus on social and environmental equity in design. She has a background in experiential design through community and education institutions, with particular interest in inclusive cultural spaces. Jackie has experience in practice at Hacker Architects and as a public agent at Prosper Portland, working with community partners and the city alike. She has worked with young people across the country and has been an architectural critic at University of Oregon, Portland State University, Philadelphia University, Drexel University, University of Pennsylvania and Syracuse University.

Lillyanne Phạm (they/bạn/she/em/chị/LP) was raised by Việt refugees in a trailer park near cornfields and suburbs (b. 1997). LP is a multimedia storyteller, placekeeping facilitator, social media scholar, and cultural worker. LP grounds their work in ancestral knowledge, the world wide web, community-powered safety, and emotional emotions. Since graduating from Reed College in 2020, LP and their work have been rooted in East Portland exploring the power of BIPOC youth decision making. LP also builds community as an organizer and member of Metro’s Equity Advisory Committee (EAC), the Contingent’s SINE and ELI network, 2022 Atabey Medicine Apprenticeship, and virtual care lab. You can follow LP’s work on IG: @lillyannepham or website: lillyannepham.com