Visual Intentions

December 4, 2022

Text by Laura Glazer with Eliza Gregory

“I really like the capacity for art to ask questions as opposed to trying to answer questions.”

Eliza Gregory

I wanted to be a photographer and then I didn’t. Well, that’s kind of true. I have always wanted to take photos because I believed they were the fastest way to make, share, and keep beautiful things, especially beautiful things that were too expensive to own. I studied photography in college and before I graduated, I told my classmates and professors that I wasn’t going to earn a living from it. (I wish I had thought to ask myself what I would do instead but eventually I figured it out. Kind of.) If you asked me why I didn’t want to earn a living as a photojournalist or commercial or editorial photographer— all of which were natural and available next steps after graduating— I would’ve told you that I couldn’t stomach anyone directing how I saw and photographed the world; I only wanted to see what I thought was in front of me or what I created with other people. While I adore my undergraduate professors and think of them daily because of the work ethic and technical skills they taught me, I wish Eliza Gregory had been in my undergraduate life. I imagine how the development of social practice as an art, along with her collaborative and participatory project experience, would’ve helped me develop a career for myself as an artist and photographer sooner and more confidently. After our conversation, it was clear to me that while I consider myself an artist, I’m as much a photographer as I ever was and ever wanted to be.

Eliza Gregory: Hi!

Laura Glazer: Hi! So nice to meet you.

Eliza: Likewise!

Laura: Thank you for making time to talk with me.

Eliza: Oh, of course. It’s fun. I wanna hear about your New York Public Library Fellowship. That sounds so amazing.

Laura: It was amazing and I feel pangs of missing the place and the people.

Eliza: How long did you hang out there for?

Laura: I was there for three weeks. I gave myself one of those weeks to acclimate, so it was really two intensive weeks on-site in the library’s Picture Collection. I will return in March to launch the publication or at least do a work-in-progress presentation.

Eliza: Tell me a little bit about it. I am so curious. I want to hear about that because I’m teaching my students right now about visual research and also thinking about how to integrate that into my own projects. And it’s just fun hearing about what you found and what you’re making from it.

Laura: Well, I went there for the first time in 2018 and I casually gave them my business card and said, Contact me if you ever need another person to do an Instagram takeover. And they did! So in 2019, I did a takeover of their Instagram using the digital collection from home in Portland.

Eliza: Cool.

Laura: Of course, I had this deep desire to know what it was like to actually be in the Picture Collection doing research—do people talk to each other? Are people looking at what everybody else is looking at?—I had this longing to know what it was like to physically be in the place.

Last year I spent a lot of time researching the Picture Collection and Taryn Simon’s project on it called The Color of a Flea’s Eye. Then in November 2021, I visited New York and stopped by the Picture Collection to say hello to the librarians and to see Simon’s exhibit.

A few months later, I interviewed Jessica Cline, the Picture Collection director, for the Winter 2022 issue of SOFA journal and she mentioned that they were launching a fellowship. I applied and was accepted as one of four fellows. My project evolved while I was there and I’m calling it See Also, a phrase that comes from a library term for a cross reference.

Eliza: That’s great.

Laura: Instead of researching a subject heading within the Picture Collection, I essentially researched the researchers.I started with what they were researching, and then went into a “see also” of, Oh, you’re researching Mary McLeod Bethune? What else do you do? Oh, you design custom flamenco dresses. Great. Can I come to your studio and see them? Okay. I’ll see you on Monday.

Eliza: That’s so rad. Oh my God. I love it. I’m like an—I don’t know what we’re calling it—affiliate or something of this new foundation called the Flickr Foundation, where Flickr, the photo platform has gotten some money to try to make a 100 year plan to think about what it means to conserve the 50 billion photographs on Flickr right now! What does it mean to treat that as a site of cultural heritage and actually think about how it is preserved going forward?

Of course, the way I think about it is like what you’re doing there. When and how do those pictures come back into the world? Or when do they become objects? When do they stay digital? How do people use them? How are people interacting with them? One of the great things that George Oates—the woman who is the head of the foundation—is talking about is, What’s the role of ritual in communication and is there a ritual-like translation that happens every few years from whatever the current format is into the next format? Because that’s what’s happening all the time, you know? Are we even gonna have JPEGs in a hundred years? What’s gonna be the equivalent mechanism for accessing visual data? So from what you’re saying, I’m like, Oh, this is so great! It ties in with other random things I’m thinking about. I don’t really know how they all come together in my own practice.

Laura: Well, that is one of my questions for you. Where are you right now with the intersection of photography and socially engaged art? That’s a big question and I just asked it casually like it’s small talk!

Eliza: There are a few different ways I talk about it.

In my own practice, I was really interested in telling stories about people. But as soon as I started to do that, I ran into all these ethical questions about the objectification of a person. When we literally make an object out of a person—the photograph being the object—what are the ethical implications of that? I started to solve those problems or engage with those questions through social practice mechanisms. That’s how I got to social practice, because I just started to build out the relationships and the accountability and start questioning each choice that you make in the process of representing another person or representing a story. Then through that interrogation, I started to have more and more other stuff going on in my work that was not the picture, but that still was connected to the picture. That’s what I really look for now when I’m engaging with other photographers’ work—what is happening outside of, around and beyond the picture?

I think photography is such an amazing tool and it’s used in so many incredible different ways now. Sometimes I have an optical engineer come into my History of Photography class, and he talks about all the different lenses that go into a Roomba or all the different lenses that are inside of the way we read COVID tests.

Photography is everywhere and trying to say anything clear about it is really hard because it can mean so many different things. Along with that, we’re inundated with photographs. We look at them so much. I feel like the historical fine art photography dialogue of the last 70 years or so—where there was this big fight to make photography be seen as a fine art and then to fetishize it—has become really obsolete. That dialogue was all about telling a story and having layers of information in the frame and this myth that you could get a lot from the experience of simply looking at a picture with nothing else going on.

Now I think it’s very clear that a picture can mean one thing in one context, and the same picture can mean the opposite thing if you have slightly different information surrounding it or a slightly different location that it’s being viewed in or a different caption or a different picture that’s next to it. I really believe that to make art using photography right now involves really engaging with the context in which it’s going to be viewed, which includes thinking about the audience that’s going to see it. What does that particular audience bring to that experience and the location it’s going to be viewed in, and the visual material that’s surrounding it; all of that has a lot to do with social practice.

I think the people who are making the most exciting lens-based work are engaging with all that stuff. They’re engaging with the context, the audience, and they’re also engaging with all these other aspects of making art that are happening around the picture. And then there’s still a picture sometimes in there somewhere. [Laughs]

It can be really good. Pictures are still really amazing and really fun to look at. They do communicate a lot and they are powerful. I think that’s why it’s so much fun to be engaging in these questions—photographs can accomplish so much and they’re also so limited.

Laura: In what you were just saying, I imagine the picture just getting smaller and smaller and smaller and the people in the picture getting bigger and then the image is super tiny. The image is becoming less and less of a focal point.

Eliza: The flip side is I’m still teaching in a photography program and there are so many skills involved in controlling what goes into a picture, how you make an interesting picture, and how you get something that has nuance and that is interesting to look at more than once. How do you make a picture that unfolds more and more meaning as you engage with it? There is still so much to talk about within the frame—it’s not like that’s gone away, but I think in terms of building lens-based artists now, I really try to bring in all those other questions.

Laura: What is the relationship between your teaching practice and your art practice?

Eliza: That’s a good question and ever-evolving. Recently, I’ve really been trying to connect them in a big way. The venn diagram of my practice and my teaching is almost a single circle. I’m trying to make art through teaching, using the social architecture of the classroom as my project structure in a certain way. Within that, I engage my students in this back and forth dialogue. I offer a bunch of research and ideas to the students and they respond to that by making art, and what they make influences my next class and my own artwork.

I’m learning from them, they’re learning from me, and they’re influencing what I’m making and I’m influencing what they’re making. I’m using the timeframe of a semester and the social form of a class to create a container in which they make things on their own, but those things come together to become a cohesive product that we bring to a public.

Laura: Can you give an example of that?

Eliza: I’ve thought about creating a public presentation of our work in three different ways. What are the main mechanisms through which pictures meet an audience right now? Exhibitions, the internet—which could involve social media as well as a website, which functions as an online exhibition—and then through publications.

I’ve been testing out all three of those as the containers. We’ve done a couple of different public exhibitions and we’ve made that set of books called Books About Place, and we’ve done an online exhibition through building a website.

Laura: That was a great answer! I’m teaching for the first time in person this term and your answers are really powerful as I make my lesson plan for tomorrow; I’m teaching a class called Ideation in the School of Art and Design’s CORE program.

Eliza: Tell me about that! That’s actually something I’ve been struggling with. I’m teaching an elective course that’s all about relationships to land. We’re working toward an exhibition that will be about our understanding of relationships or lack of relationships to land, what that means, and what that looks like.

I asked students to bring in five experiments that they had done–potential projects that they might engage with or that they might want to do, a little sketch of five different ideas. But that turned out to be really, really difficult for my students this term; they’re not used to coming up with ideas like that. They were stumped by that and I had thought that would be a great starting place or an easy first step. They really weren’t prepared for that exercise.

And I thought, Oh my gosh, what does it mean to have an idea? What are the tools? What are the tools that I use to have ideas and how can I offer that to them? So, I want to hear what you’re doing because I think you might have the answers for me.

Laura: I was the teaching assistant for this class last year and we set up the use of a field notebook. Every week the students were responsible for making something on at least four pages in the notebook, and often we would give a prompt.

For example, I was just grading week two’s assignment where, as a class, we took the streetcar to this little-known park in downtown Portland called Tanner Springs Park. Only one of the 22 students had been there and most had never ridden the streetcar. So the field trip became a series of “firsts.”

Then we spent half an hour in this one block by one block park, picking out at least 10 things we found curious. In their field notebooks they could do written descriptions, drawings, or take photos to print out later and then add to the notebook.

That’s an example of how we’re using experiential learning to practice noticing. I also did a brief introduction to Sister Corita Kent’s use of viewfinders.1 I gave everyone slides and told them how to deconstruct the slides to remove the film and just use the holder as a viewfinder. I think most students forgot to use it because it was so exciting to be in a new place in a really beautiful park in the heart of the city that they almost didn’t need to focus in that way. The next class we will be talking about that experience and how to continue extracting ideas from it.

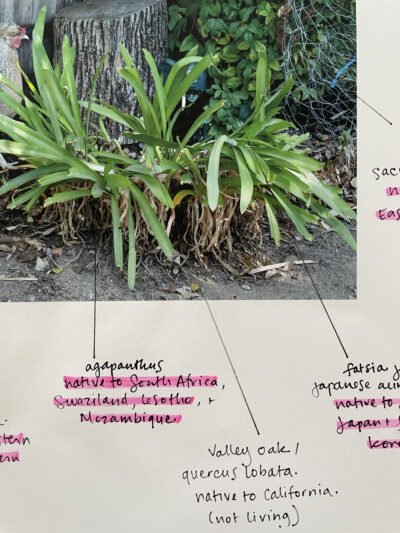

Eliza: That’s so cool. I love that and it’s very validating. I impulse-bought 18 scrapbooks and gave each student a scrapbook. My students have also struggled with layout and understanding the aesthetic language of the arrangement of elements on a page. I ask them to deal with context all the time, and you have to build up a little bit of a design sense for how to build that context visually. That was something we learned last year when we did the books with them. These students have never made scrapbooks, they’ve never arranged things with visual intention. I’ve also been having them try to make some pages in their scrapbook just to build up a practice of recording their ideas in an aestheticized way as opposed to just a linguistic way.

Laura: There was also a presentation I gave on wild note taking. I went through examples of writers and artists who use the context of the page to explore their thoughts visually and in text form. For example, Oliver Sacks is documented as being an annotator and his notes are really great. I’m happy to share the deck with you.

Eliza: I would love that so much. That would be a huge gift. Thank you.

Laura: I would be honored to share it. I like thinking about more people being exposed to methods for turning a page of notes and thoughts into an artwork.

Eliza: Me too. I grew up having what my mom called “the art center.” It was this little set of cubbies that she got. It had weird stuff for collages and pens and paper and we had an Apple IIe2 and so for a long time there was all the extra printer paper with the funny little things on the side.

It’s still there in my parents’ house, this weird pile of stuff to make things. That was just something that was always available and I made scrapbooks and stuff like that. My students are not coming from that same environment. That has been good for me to realize and then try to offer that in a way that makes sense for where they are now and for what we’re doing.

Laura: I’m curious, where did you grow up? Where was “the art center?”

Eliza: In San Francisco, in the Richmond district, in the fog.

Laura: I’ve been reading about your work and studying your projects and thinking about San Francisco as this core place in your practice. Is that true?

Eliza: I’ve had sort of a moving practice because I have lived in a bunch of different places. But I did grow up in San Francisco and then I lived there again recently. Now I live in Woodland, California, which is close to Davis and close to Sacramento. It’s a town of about 50,000. I’ve lived here for five years, but I lived in San Francisco for seven years before that. I was making a lot of projects there and my parents are still there. Definitely that’s my hometown, my “home place.”

Laura: Would you consider California more broadly as a core place in your practice?

Eliza: Definitely. I’ve also lived in Southern California a couple different times and my husband is from Southern California. We go there a lot because his parents are in Santa Barbara now. In our family we have this sense of a California identity that includes relationships to a bunch of specific locations within California.

Laura: When you were talking about the social form and photography, it reminded me of when I was studying photography at Rochester Institute of Technology and declared, right before I graduated, that I wasn’t going to earn a living professionally from photography because I really wanted relationships with people to be primary and photography to be secondary. I didn’t know about art and social practice until 2017—like 20 years later! For you, were those things always running alongside each other? How was photography connected to people in your early life? How did you find this direction?

Eliza: I studied photography. It was actually accessible in my elementary school. I took my first photo class in seventh or eighth grade, and then was able to do a class or two in high school and then in college.

In my family there are a lot of people who had made pictures in previous generations. I also saw examples of a visual record of a family life coming from both sides of my family back a couple of generations. I had lots of pictures of people around me, in these subliminal ways. I like people and I’m curious about people. I also felt an interest in service. What does it mean to be of service and also to make pictures? I think those were questions that maybe I couldn’t articulate so clearly, but that were operating behind the scenes.

Somebody gave me this book called In Our Time: The World As Seen by Magnum Photographers, which is a collection of greatest hits of Magnum photographers. That was when I was in high school or eighth grade or something. I really thought that book was amazing because I was looking at these pictures of people from all over the world, and conflicts, and history, and was thinking, Oh, this is a way that I can learn about other people—through looking at pictures—and that seems useful. I had that in my mind as what I wanted to do, but I didn’t really want to be a war photographer. I tried being a journalist and worked for the school paper in college. I also had some jobs photographing community/university partnerships when I was out of college working in Arizona and I like that kind of documentation, but I really like the capacity for art to ask questions as opposed to trying to answer questions.

Basically, I was interested in the idea of making pictures in order to help people understand each other and build compassion. But my first efforts at that just isolated people further and accentuated differences.

I went to work for the International Rescue Committee which was providing social services in the refugee camps in the western part of Tanzania. That’s where I made some of these pictures and I thought, Oh, well, you know the culture of Tanzania in these refugee camps and the town where I’m living is really different from what I grew up experiencing in San Francisco. So won’t that be interesting? I’ll be able to build this common ground by showing an audience that I have access to what I saw and experienced in this other place.

I showed these pictures to really wonderful people who taught at Arizona State University like Stephen Marc and Bill Jenkins. They said, Eliza, that’s not what’s happening here, we are not seeing what we have in common. We’re seeing differences here. Also, you are a white woman taking pictures of Black people in Tanzania and you can’t bring that back into an American context and have that just be not a big deal.

I was trying to make pictures of people in one part of the world and show them to people in another part of the world and that just accentuated differences as opposed to highlighting what we have in common. So I was like, Oh, well that was a bust. So what am I gonna do? How can I solve that problem?

Then I thought if I can’t make these pictures that are going to talk about compassion and common ground through that mechanism, what if I take pictures of resettled refugees in Phoenix because these are people coming from cultures all over the world, but then have to adapt to this place and the place will be recognizable even though aspects of the life that these different families are creating are different. Maybe that is the visual entry point for me to create this dialogue that I want.

Then I worked with a nonprofit organization in order to meet resettled refugees living in Phoenix whom I could ask to photograph. Through that process, I had a whole different kind of accountability. They were a really wonderful organization that built relationships with their clients. They were the ones who helped me realize that we have to get the clients who are in the pictures to be able to see the show; you can’t just take a picture of somebody and then show it to somebody else and have that not be weird. You have to make it possible for them to access what we’re doing together.

We were able to create an opportunity to show the work at the ASU Museum of Anthropology, which of course is a little weird. I mean, anthropology as a discipline —there are a lot of things to be unpacked there. But that was where we were able to show the work. Then we got this corps of volunteers to actually drive people to the opening reception because a lot of resettled refugees didn’t have cars or didn’t have easy access to transportation to get on campus. And a college campus by itself is not easily navigable to someone who hasn’t been there before.

All of a sudden I had this partner that could bring up the logistical issues that were connected to the ethical issues, and then we could solve them together. Going through all of that, I started to become more aware of what I was doing and the implications of what I was doing. That fed back into how I started to build projects and how I started to conceive of structures.

Laura: That was great for many reasons. The first of which is I just got off the phone with Wendy Ewald.3

Eliza: Oh, she’s the best, what an amazing person.

Laura: She’s boarding a plane to Portland to be a visiting artist for the next week at Dr Martin Luther King Jr School Museum of Contemporary Art (KSMoCA.) Hearing you talk about Tanzania means that, of course, I’m thinking about Wendy. What role has Wendy’s work played in your practice and projects?

Eliza: She is really somebody I look up to a lot and I’m thinking about a lot. Certainly the shift in the last couple of years toward trying to make art through teaching comes directly from being exposed to her projects through Harrell4 and through the Art and Social Practice MFA Program. Also through Julie Ault, who turned me onto this documentary that you may have seen called Stranger with a Camera that was made by Elizabeth Barrett from Appalshop—she made a film about Wendy, too. It’s all part of this same community of people thinking about some of these issues around representation and storytelling and what it means to support people telling stories about themselves. One of the things that Wendy says is—I can’t remember whether it was in a conversation with her or something I read—you’re making art through teaching, and the students are making these photographs, but they have to make good photographs, you’re teaching them how to make good photographs.

It all starts there. The teaching has to be really good in order for the rest of this to work because that’s the exchange where it all starts. If you, as the teacher, aren’t helping the student really make something that they can feel proud of and that they feel expresses something that is important to them, then all the rest of it will collapse.

Laura: When you’re talking about Wendy saying you’re teaching them how to make good photos, what does that mean to you?

Eliza: I was thinking that in this context I don’t know how to measure what I’m doing against “good photographs” as a standard, because I think what I’m teaching them to make is so much more amorphous. I don’t exactly always know what’s happening in what we’re doing. But the way I connect what I’m doing now to what I just talked about with Wendy is that it’s really important to me every time that my students feel proud of what they’ve produced. I’m really looking for that as one of my evaluation metrics as opposed to a grade.

Part of what I think can happen through a “teaching as art making” structure is that it allows the students to make something more sophisticated and different than what they could make on their own, which allows them to feel surprised by themselves and excited about their work in a way that can be a type of momentum that carries them forward once they’re outside of that class structure.

I think a lot about teaching as building my students’ muscle memory—the way you would on a sports team, practicing drills so that when the time comes for the game your body just knows what to do. I ask myself, How am I leading them through a series of actions that they can then repeat afterwards, even if it’s in a totally different context or with a totally different outcome? How do I allow them to feel comfortable and empowered doing a series of things that then will let them do that again without me?

Laura: In what ways have you observed that happening?

Eliza: Some of it is what I hope is happening, because I’ve just started my career as a college-level teacher, so we’ll see. Some of that takes a little while to come to fruition and to understand if it’s really working and certainly there’s always room for a lot of improvement. This is sort of a madcap way of teaching because it’s different every time and you’re always figuring things out and you’re making art as it’s happening and making art is a notoriously unwieldy and unpredictable process. You’re throwing students into that and there’s a lot of discomfort and frustration for them, even as they also grow a lot through it.

One answer is—I have no idea. But another answer is, I did have a great chat with a couple of students who graduated last year. I had them all year last year when they were seniors at Sacramento State. Now they are creating exhibition opportunities for themselves, and they’ve applied successfully for things and they are operating in the world as artists, and that’s what I’m aiming for and that was really exciting to me.

Laura: Can you tell me a little bit about how you think about exhibiting social practice work in museum or gallery environments?

Eliza: There are a bunch of ways in which that can work really well. I have been thinking a lot recently about what it means to invite the audience into the research in a research-based practice, whether it’s a social practice or another kind of practice.

Thinking about the scrapbook again, what does it look like to let an audience see my ideas developing? I’ve done that in two ways in the last two years. Last year, I put a lot of the students’ work on display. I basically cherry-picked four people from each of the previous two years whose work had been not necessarily the best but the most interesting to me in terms of ideas that I want to be carrying forward in my own work.

I was trying to show some back and forth. First, these students made this work in my class based on the techniques and ideas that I offered to them. It’s connected to me and my work, even as it’s also their work. These are the works that I’m the most curious about and that I’m still thinking about and want to take forward. Whether it’s because of the aesthetic solutions they came up with, or the subjects they photographed, or the way they put things together, or the research they did, each one was a little bit different in what they showcased. I showed that alongside some of my own experiments and messy notes and things I’m working through in my own practice.

This year I showed the work of other artists who are doing things that I’m really interested in—who are pursuing similar ideas and lines of inquiry to me, but have actually been able to make an aestheticized thing as a result of that. Whereas I’m just reading the books and thinking mostly about this particular project and still fussing around.

In some ways, those are two efforts of showcasing a social practice because I’m making this art with my students and I’m making this art through dialogue with my colleagues and with other artists. I’m trying to show all of that even as it also functions as a conventional sort of visual art exhibition experience.

One thing was really exciting to me in the first show and it has informed a lot of what I’m doing now. This nice guy and his partner were in the show and he said to me, “It seems like you are really good at connecting with your place. Could you teach me how to connect with my place? I want to be able to do that.” I was like, that’s so wonderful, what a great idea! Maybe that’s what the [Placeholder]5 project is: allowing the audience to come with me as I try to connect with my place and then offering different strategies for how that could happen for you.

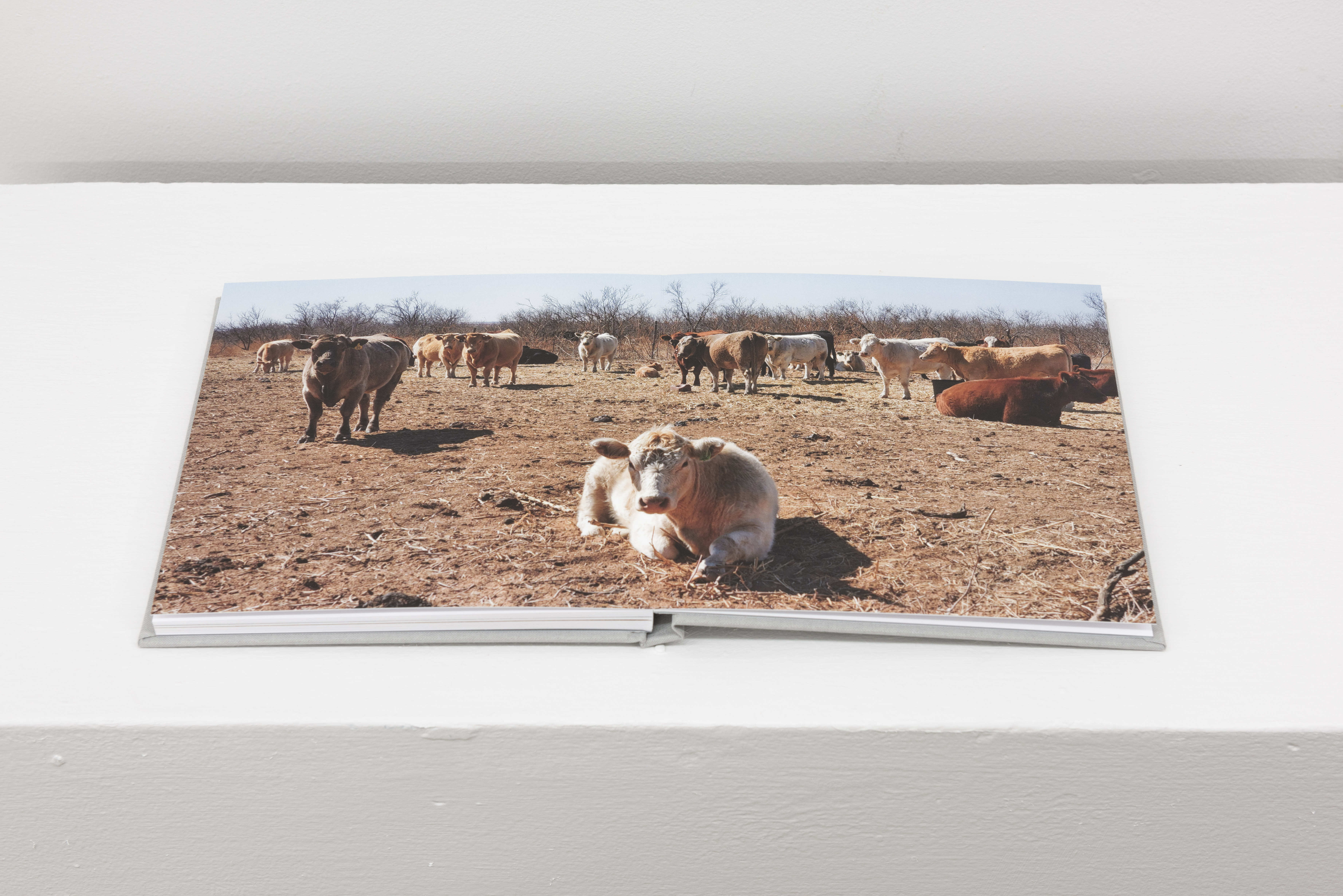

In the little show I did this year, I put in Travis Neel and Erin Charpentier’s project called The Mesquite Mile.Travis and Erin were in the MFA Program when I was. Now Travis teaches at Texas Tech in Lubbock and Erin is a professional graphic designer. That is a really social practice-y project where it’s all about these partnerships and relationships and transplanting native plants that are seen as weeds for ranchers into the urban core of Lubbock and creating the native habitat in the city.

They’re doing curb cuts and getting memoranda of understanding6 with the city so that they can reorganize people’s yards in a way that the water flows properly to irrigate the mesquite trees they’re transplanting. This is such a cool project where all sorts of different crazy stuff is going on that’s very much about people connecting with each other, as well as people connecting with land and understanding the history of this land and the native plant communities that are past and present.

In order to put that on display, they have this wonderful video that they commissioned of a mesquite tree being dug up from a ranch, carried into the urban core, and then being replanted in somebody’s yard. That was on display and they sent me some photographs that document the project.

There’s this really interesting thing that the program helped me identify, which was, in social practice, if you can make the documentation of the work as sophisticated and rich as the work itself, then you can show it. That sometimes is a pain in the butt and it doesn’t make sense for every project. Sometimes the real-time enactment of the project is the main thing and it should be the main thing and telling the story of it afterward doesn’t need to be as complex. Certain projects have a great, really quick story that can travel far beyond the initial audience of the project very effectively.

Sometimes the story is more complicated or more fragmented and can’t be condensed so easily. In that case, sometimes it makes sense to take this other approach. Certainly, I’ve enjoyed taking that approach and making publications and things that tell aspects of the story of what I’ve been doing and invite the audience into those phases of a larger project.

Laura: What are some details of your non-professional and non-artistic life?

Eliza: It’s very chaotic! I have my studio and it currently looks like a hoarder palace. It’s really a mess. I have 10 chickens in what I call my dystopian garden because I let them free range in there and they just dig everything up and destroy everything. I have two dogs and then I have two daughters who are 10 and 3. And my husband Ryan works at UC Davis, running the Center for Community and Citizen Science, and that’s what brought us here to the Central Valley.

Laura: It was really nice to hear you talk about showing artistic research and process in a museum environment because I gathered all this research at the library and what I find myself talking about is my process. When I share that with people, they get so excited. They’re like, You ended up in that person’s apartment at midnight after going to a bunch of gallery exhibits?! That is truly how I roll in the world; I could end up in Paris tomorrow if I ran into somebody on the street and we started talking and they’re like, I gotta go to Paris. And I don’t want the conversation to end. I’m gonna go with them.

Eliza: That’s awesome.

Laura: I have all of this documentation that I’ve organized and I’m really eager to share, but I’m still figuring out how to do that. I usually make a publication and we have a museum exhibit in June, and I’m wondering how that will work. Hearing what you said is really validating.

Eliza: Julie Ault told me something that has really helped me a lot. She advocated for inviting the audience into the research. But she also said, you have to chart a pathway through that research. You don’t want to just put everything out there for people, because that’s just making them do all the work. You still have to lead them through what they need to experience in a way that is satisfying and exciting for them. That’s what a publication often forces you to do because you have to make choices— you can’t just put everything in there. That is often a linear pathway. But whether you’re doing that in an exhibition or in a publication or in a talk or whatever, that’s been a really nice idea for me to hang onto, that you’re really leading somebody down a path and you don’t want to put the onus on them to take everything in and sort it.

Laura: I think that having a background in photography is a good foundation for making those pathways.

Eliza: I think you see Julie doing that really well in her books and in her writing, and you also see it happening in Group Material, in the AIDS timeline shows or all those early shows where you have tons of material there, but it never feels like too much, it feels like everything is interesting, everything is worth your time. That’s something I talk about a lot with my students. How do you reward the audience for the time that they’re spending with you? Are you meeting expectations or not? Are you rewarding that attention?

Laura: What does reward mean to you?

Eliza: It means, is the audience getting something out of it? Are they able to engage? Are they taking something with them that they want? Are they having an experience that feels satisfying?

Laura: I have way more questions than we could ever get to, and I love that our conversation had its own pathway. Let’s do a few lightning-round questions. What year did you graduate from the program?

Eliza: 2014.

Laura: Did you live in Portland when you did the program?

Eliza: No, I lived in San Francisco and we spent every May up in Portland. The first time my first daughter was eight weeks old and we just moved up there for a month with her and it was so amazing. Harrell and Jen7 were so great and said, You can bring her to everything. My husband sat in the Park Blocks holding her until she got hungry and then he would bring her into the classroom and I would feed her and then he would take her out again.

Laura: One of my classmates has asked each of us to ask our interviewees a certain question. So this is a question coming from Caryn, who’s in my cohort: how do you explain social practice to non-artists?

Eliza: I always say it’s art that is made using social interactions as a core component of the work. Often I follow up by saying it can be a non-object-based practice, but it doesn’t have to be. Then I sometimes follow that up by saying my practice uses photographs, interviews, relationships, experiences, events, publications, and I layer things all together.

Laura: Is there anything you want to tell me about that I wouldn’t know about or I haven’t asked you about?

Eliza: I do think a lot about the program and how it functioned, especially because I’m an educator working to educate artists to become social practice artists and photographers. In all my educational experiences, I feel like there are things that I took away as they were happening and then there are things that I’ve gotten from them later. There’s this kind of half-life of really good teaching that unfolds as you move through your life and things resurface when you’re ready for them. There are certain things that were offered to you as a student that you weren’t ready for yet, and I’ve found myself able to access those ideas later and they’ve started to make more sense later.

I think about what it means to teach like that. What does it mean to offer my students things that they can learn from in this moment, but also offer them things that maybe will serve them well later or become relevant later or unfold in their lives? I think some of the things that the program did like that for me was this experience of being in a project. When you’re in the program, you’re a participant in somebody else’s project and many times as social practice artists, you haven’t necessarily had that experience before because you’re usually the architect of the experience. I think that’s really, really valuable and wonderful.

(1) Sister Corita Kent was an artist, educator, and advocate for social justice at the Immaculate Heart College in the 1960s. One of the tools she introduced to her students was a “finder” which is an index-card size piece of paper with a square or rectangle cut out of it. “[The finder] is a device, which does the same things as the camera lens or viewfinder. It helps us take things out of context, allows us to see for the sake of seeing, and enhances our quick-looking and decision-making skills,” said Kent and her co-author Jan Reynolds in Learning by Heart: Teachings to Free the Creative Spirit.

(2) A model of personal computers released by Apple in 1983.

(3) Wendy Ewald is a photographer who for over forty years, has collaborated on photography projects with children, families, women, workers, and teachers. She is based in the Hudson Valley of New York and has worked in the United States, Labrador, Colombia, India, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Holland, Mexico and Tanzania

(4) Harrell Fletcher is an artist and the founder and co-director of the Art and Social Practice MFA Program at Portland State University.

(5) A project about our relationship to land. It is called [Placeholder] because it’s about holding and being held by place.

(6) A memoranda of understanding or “MOU” is a document that describes the broad outlines of an agreement that two or more parties have reached.

(7) Jen Delos Reyes taught in the Art and Social Practice MFA program at Portland State University from 2008-2014. She is an artist, author, and Associate Professor of Art at Cornell University.

Laura Glazer (she/her) is an artist using curatorial strategies to share exciting stories that she finds in places she lives and visits. Her work is socially-engaged and depends on the participation of other people; sometimes a close friend, and other times, complete strangers. Her background in photography and design inform her social practice, and her artworks appear as books, workshops, radio shows, zines, festivals, exhibitions, installations, posters, signs, postal correspondence, and sculpture. She holds a BFA in Photography from Rochester Institute of Technology and is an MFA candidate in Art and Social Practice at Portland State University. She is based in Portland, Oregon, after living in upstate New York for 19 years. Visit her website to see her projects and follow her on Instagram for updates.

Eliza Gregory (she/her) is a social practice artist, a photographer, an educator and a writer. She has collaborated on her projects with the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, Wave Pool Art Fulfillment Center & Cincinnati FotoFocus, the Portland Art Museum, SFMOMA, the Arizona State University Museum of Anthropology, Southern Exposure, the HeadOn Photo Festival in Sydney, and the Storefront Lab, among other institutions. Eliza’s work focuses on identity, relationships, and connections between people and places. She builds complex project structures that unfold over time to reveal compassion, insight and new social forms. She currently teaches in the photography program at Sacramento State University.