We Did This

December 12, 2021

Text by Diana Marcela Cuartas with Jesús “Bubu” Negrón

“For me the ideal would be to get the community to see itself as the artist, becoming responsible for making sure the community understands the project and uses it to its advantage. And you can leave, but the project keeps going, it’s part of the community, you can go find it.”

Jesús “Bubu” Negrón

I’ve been fascinated by Puerto Rico since I was a child. Being born in Cali, the world’s capital of salsa music, I grew up listening to plenty of music by Puerto Rican artists. Somehow, that made me feel connected with their landscapes and people’s culture, whose lives and struggles sounded very close to what living in Cali was like.

Later, when I became interested in art, Puerto Rican artists popped up again with different projects that presented an approach to art more aligned with my own interests. An art that would bring people together and generate shared memories that would make everyone’s hearts pumping with joy. An art that could happen at the beach, the neighborhood, in a fried food kiosk, or anywhere but a white cube.

In 2018 I finally had the chance to visit the island and encounter those landscapes and faces. It felt pretty much like meeting siblings you didn’t know you had. There I met Bubu. We visited his neighborhood, friends, and favorite places. Hanging out with him, I learned about multiple projects developed in such a natural manner that seemed almost magical. At that time, a term like “social practice” didn’t have a daily presence in my life, but I learned a lot about it without knowing it.

I invited Bubu to chat with me for this edition of SoFA Journal to continue learning about Puerto Rican social forms of art and the magic that sparks when people make their way together to resist oppressive structures.

Diana Marcela Cuartas: How would you describe your artistic practice?

Jesús “Bubu” Negrón: I would say that it has been a mixture of allowing myself to be carried away by the circumstances of my life and responding to those situations. I’ve never been able to be the kind of artist who goes into his studio to paint and make work every day. Instead, it’s more like I’m on a mission. They invite me somewhere and I encounter the situation, and the projects come from that. Many of those projects were created to address some specific problem that I had to experience, and the majority were communal experiences, which is something sensitive, but those are the ones I’ve enjoyed the most, where I experienced the most, suffered the most and really lived.

Object pieces often come out of those processes, but I see them more like souvenirs from the project. Because there’s this part of the art world that demands that kind of thing. Like, “Ok, cool projects, but where are the pieces?” There is a public that is like that, and if you can make that kind of artwork, why not?

Diana: Like the Colillón piece. How did the idea emerge to collect cigarette butts in Old San Juan?

Bubu: At the time, I was volunteering for other artists like Chemi Rosado and Michy Marxuach from M&M Proyectos. Spending time with them, I started to throw ideas around, which I didn’t see as art projects at the time, but they did. With the cigarette butts, I was telling them, “Damn, every day I walk around San Juan and I see all these cigarette butts between the cobblestones. It would be really cool to fill it all up with cigarette butts to make a design.” I would say it more like a joke, and they said to me, “Whoa, that’s a project, let’s do it.” And so those projects became an adventure. It’s one thing to talk about it, but suddenly I found myself picking up butts for a month to make the piece. I wound up being a character on the streets of San Juan—the crazy guy who picks up cigarette butts. And that’s when I started to take a liking to that dynamic, not of making the piece, but of what happens in the process. That was what I liked.

People would ask me, “What are you doing?” and it made me laugh because everything could be resolved by saying, “An art project.” I mean, I can do these “crazy” things, and as long as people see it as art it gets neutralized. Eventually, I didn’t know what to do with so many cigarette butts, and there was a joke about making a big one, the colillón. That piece came out and it was neat, but I think the real artwork was actually the indirect performance that happened every night, that crazy person picking up cigarette butts. It wound up being a participatory performance, which was something else I didn’t expect. I started off doing it alone, but suddenly people wanted to help me, and it became a big activity.

All of this, as I said, was circumstantial, because it isn’t something you can plan. And I think it was the project that most led to me giving myself a kind of power, let’s say, of sharing with people outside of my orbit.

Diana: So, it was hanging out with Michy and Chemi that you got interested in making this kind of art. What were they doing that caught your attention?

Bubu: Well look, obviously I was never able to get used to school, to the academy. I don’t know why I couldn’t do it.

Diana: But you went to college?

Bubu: Yeah, I studied at the School of Visual Arts in San Juan. I was always dealing with painting and drawing, like everyone else. But I left because I found M&M, and they began to support me, and if I was already doing the things I was going to school for, why would I keep studying? With them, we would do whatever projects we wanted. They weren’t worried about selling, we didn’t have to make a proposal. It was like, you’d be sitting there and you’d say, “Man, I’d really like to light a fire in that chimney,” and then Michy would say, “Let’s do it!” You didn’t have to go over a why or how much, not like the proposals you have to write to win a grant these days.

And so that really influenced me, I have to admit, because if things had been different I would be someone who makes paintings. But I was motivated by that way of taking an idea to the extreme. The motivation I got from her at the time was a catalyst, you know? Very few people will tell you, “Let’s run with it and I’ll support whatever crazy thing you want to do,” and I come from that school.

It’s not like that anymore, but that’s probably why the vision for so many of our projects was to try and create something transcendent, something that will stick in people’s memories. There are projects that people from town still mention with the same excitement as when they first happened. And those are things where you say, “Hell yeah, it was worth it,” even though you didn’t make any money. That’s the part I love to experience. I’ve always tried to make it so that the projects bring me closer to myself, to my friends, to the people, to where I come from, to we who have to make a living working in other things, like you and I right now.

7 Days in Igualdad, 2004. Añasco, Puerto Rico. Photo courtesy of the artist.

For 7 Days in Igualdad, Bubu reignited an abandoned chimney from a sugar cane hacienda in Añasco, Puerto Rico. In an effort to bring visibility to a dying community, he worked with local collaborators to light the chimney twenty-four hours a day for a week. The resulting smoke signified a concerted social action and the reconsolidation of kinship, symbolically captained by the reignited chimney’s inscription “igualdad” (equality).

Diana: What was your first close encounter with the art world like?

Bubu: Well, obviously it was with M&M. At the time they had gotten really far. Michy is an incredibly visionary person and is respected in that world. I had an idea that she liked. I don’t know if you’ve seen a piece I did called Primeros Auxilios (First Aid). Well, I remember, that was the first crazy thing that they pushed me to do, because I didn’t dare.

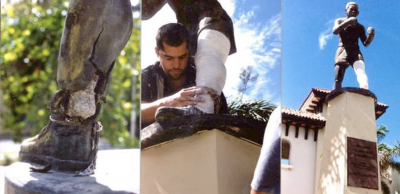

There is a statue in Old San Juan of a boxer who is an icon in Puerto Rico. As a kind of joke, I told people in San Juan that, with all their self-importance as the capital and all that, they had to salute some guy from Barceloneta, the little town where I’m from, every day on their way home. Until someone told me the statue was broken, and I didn’t know that. So, I went to see it and there it was, it had a broken leg. I started to think, “Well shit, this guy was from my town, and if the statue is broken, the memory has been forgotten. I need to give him first aid,” and I told them I wanted to put a cast on it so that at least it wouldn’t look so bad. And their response was like, “Whoa, let’s get on it!” And they took me to a place to buy the plaster, they hoisted me up there, even though I was seeing it as a prank. That was the first piece that Michy took an interest in, and she took it to ARCO. I didn’t know what ARCO was and it turns out to be in Spain. I had never left Puerto Rico, but I won a grant and got a ticket, and that was when I started to see the glamour and the way that world works.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Diana: Speaking of art fairs, can you tell me about Back Portraits?

Bubu: I remember that it was my first fair project. I was interested in these issues of the collector’s role, exclusivity, originality, price. So, I thought I would go as an artist on the lowest rung of the art world, which is the guy who sells drawings on the street. To make it different, instead of drawing people’s portraits, I drew them from behind, which was easier for me too. During the fair, what I did was sell the original pieces to the general public and the “copy” to the collector. And I realized that a lot of “normal” people go to art fairs, families and children who go because there is an event happening in their city, but they come up against the fact that everything is incredibly expensive, and they leave with this feeling of, I can’t have this. I saw it, but I will never have it. I sold them for a dollar, so suddenly they could buy an original drawing by an artist, and they went home happy. I made a photocopy of each drawing, and at the end, I made a mosaic with all of them. That was sold at a collector’s price. It was a way to force the collector to have the copy.

Back Portraits (drawings), 2002. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Diana: And how do you balance that encounter between the art world and community work in your projects?

Bubu: For example, in Bolivia, Cancha Abierta (Open Court) was one of the projects that turned things upside down in my life and made me mature. That is, when you go and you realize that you’re there as an intruder, that no one is asking you to be there, that you have a bunch of money in your hands, but people don’t have electricity or water, and you have to spend it on some stupid project that you came up with.

I was in Puerto Rico thinking about things based on what I had found through Google. But when you get there, you find a community that has nothing and you go into shock. You start to ask yourself, why make drawings when I could develop something functional that will persist? I remember I told them, “The project you chose, I can’t do that anymore,” for the reasons I just told you about. “Instead, let me clean the court,” because the town’s basketball court had been buried in mud and I wanted to clean it, and that was the project, that’s what happened.

In the end I justified it as land art, that it was some kind of contemporary archaeology for recovering the court. Everything was as if it were an archaeological discovery. There you can play your hand and meet the demands of the art world, you give the curators something to write about. But also, the people from the town realized I was trying to help them. They didn’t care if we were making a work of art. Instead, we did something functional. And I’ve always liked it when those worlds meet, the people coming together with the curator and the art world, and they can converse and they both understand the project. When you make it so that the community that you’re working with sees that this is an art project, though we’re cleaning up a basketball court, for strategic reasons it’s an art project. That’s the part I like.

Diana: I’ve also noticed that you’re particularly concerned with the continuity of the process, with what happens after a project is completed. How do you see the possibility of long-term continuity in these kinds of projects?

Bubu: What I’ve had to recognize when working in communities is that there are two rhythms. Art goes a mile a minute, from exhibition to exhibition, right? Communities don’t. Communities go much more slowly. And that’s the dangerous part of it, when it becomes “We did something with the community, on to the next show.” Because if you really want to work with the community you have to stretch that out. It’s difficult because the gallerist doesn’t care if you’ve been bonding with them, they only care about, Where’s the photo? Where’s the video I’m going to take with me? And those are the things about the art world that leave a bad taste in my mouth, but they also made me understand that I can find other sources. For example, there are other organizations that don’t have anything to do with art but that have a ton of resources, and the people are on the mission to help a community.

For me the ideal would be to get the community to see itself as the artist, becoming responsible for making sure the community understands the project and uses it to its advantage. And you can leave, but the project keeps going, it’s part of the community, you can go find it. To me, that’s what should happen, because if it doesn’t, we aren’t developing anything.

In the case of the project Brigada Puerta de Tierra, the phenomenon I experienced was with the children. As always, they’re the most curious. I had worked with children before and I knew how to deal with it. That’s where the Brigada (Brigade) community came from. None of them cared about art, but they saw the potential. They went to see universities, they were able to travel, and all of those opportunities were built through the project. Because we’re fighting for a real cause, people can’t think of it as “Bubu’s project.” I was always trying to get across that it was Brigada Puerta de Tierra, that the community was the artist, that when a curator arrives, anyone can talk about the project. Because when you set out to work on a social project, it’s collective. It doesn’t belong to the artist because we are all the project. I’ve told curators not to put my name on that project, but they say it’s too hard to move the project without the name, and it’s messed up that that happens.

Diana: And why not use that power of the artist, if you know that having your name attached to it will give the project greater visibility?

Bubu: Because the intention was to hand that power over to the community. What happens is that you also have to learn how to empower the community. Right now, we’re making it happen. The curators know who the Brigada is, and they can go and offer them a grant. Although you’re right, if it helps to hear a name, then do it.

Now the members of the group say “Brigada Puerta de Tierra,” and everyone is impressed. When they introduce themselves, what do they say? I was at Harvard, I was in New York in such-and-such museum, I went to England to such-and-such museum, we won this international prize. And that game of taking them here and there has created a really strong CV, but it’s about using that world to their benefit. The government doesn’t understand what that is, but they see that the collective was talking internationally, was featured in a magazine, and they understand that something is happening there. But it has taken like five years to make that happen.

I’ve also learned to not be so harsh about the art world, because the truth is that it’s limited, but you can use it to turn the tables on a bureaucrat. I love that.

Diana: And what do you have to do so that people participate in an authentic way and are “empowered,” as you say?

Bubu: I think there are a lot of ways to do this, and they all involve talking honestly. Telling the truth about the limitations of the project. So, if the community sees a use for your idea, I think that things start there. I think that’s where the connection is, when they see that your project isn’t the wild imaginings of someone who came and did this random crazy thing. Instead they can get to that place where they say, “Wait a sec, out of all those crazy ideas, this person is making sense and we can use this.” Another way is by paying attention to them and using art as a mere facilitator.

In the case of Brigada, it’s much more political because it directly affects me. I live there, and although we haven’t achieved a lot of the things we wanted, if you look back, Brigada Puerta de Tierra is a social organization that is well established in the neighborhood. That’s a big achievement. At least one step has been taken.

Diana: Also, the fact that it’s a space where people can get together and hang out and share ideas, which is something that supposedly doesn’t matter but is part of what gets people out of bed so they can keep living.

Bubu: It matters to the community. At the end of the day, it’s something else they appreciate about Brigada, which brought together multiple generations. When they saw that a child could have opinions and their opinions could matter as much as those of an adult, that blew their minds. But I do believe that, in the end, the best thing you can do is to pass unnoticed. Without losing track of the idea that we’re making art but lowering the artist ego so that people can empower themselves and say, “We did this.”

Jesús “Bubu” Negrón (he/him) is a Puerto Rican artist whose work is characterized by minimal interventions, the re-contextualization of everyday objects and a relational approximation to artistic production as a revealing act of historical, social and economic proportions. Negrón lives in the neighborhood of Puerta de Tierra in San Juan, where he is part of the Brigada Puerta de Tierra – a grass-roots community organization for the preservation and wellbeing of the neighborhood, its history and its people.

Diana Marcela Cuartas (she/her) is a Colombian artist and a current student in the Art and Social Practice program at Portland State University. In 2019, she moved to Portland, Oregon, where she has been working independently for the promotion and exchange between Pacific Northwest and Latin American artists. Currently, she works as a family liaison for Latino Network, serving immigrant families through school-based programs at Parkrose, Benson, and McDaniel High Schools.