A Pause Anywhere is a Gift

December 5, 2023

Text by Luz Blumenfeld with Judy Blumenfeld

-Judy Blumenfeld

“Everyone is a teacher, everyone is a learner. Even as therapists and analysts, we’re having an encounter with someone. It’s not that I’m this smart analyst and I know everything about mental health and I’m going to make you better. We’re trying to have a relationship and an encounter.”

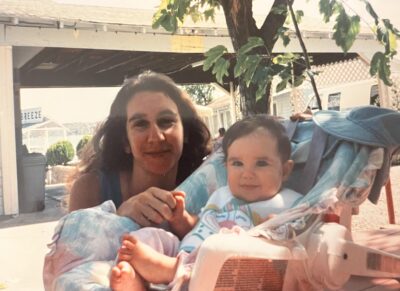

My mom and I both recently had our Saturn Returns, (my first and her second). Your Saturn Return is when Saturn returns to the place in the sky that it was in when you were born. It happens about every 29 years and is known as a time for big life changes and growth. I was born during my mom’s first Saturn Return, when she was 31. I’m 31 now, and my first Saturn Return has just concluded, during which time I left Oakland and moved to Portland and started graduate school.

My mom went back to school when I was in middle school and got her Masters in counseling psychology and Drama Therapy. I think that her work in psychoanalysis has actually transformed our relationship in a big way. It feels easier to talk through complicated things now. It feels like there’s more room for trying to understand each other.

I’m really proud of my mom right now, and I’m excited for both of us because we are both doing the work we love and really want to be doing now. For me, that work is getting my MFA and teaching and deepening my understanding of my art practice. She just finished psychoanalytic training at the Psychoanalytic Institute of Northern California (PINC). This conversation took place just before her graduation where she read a paper she wrote to a big group of people over Zoom. In it, we talk about intergenerational trauma, Palestinian liberation, and the overlaps in our practices.

Luz Blumenfeld: What are you doing in your practice right now?

Judy Blumenfeld: I’m finishing this extensive psychoanalytic training that I’ve been doing for six years now. My graduation paper is a lot about my emergence, or becoming how I was thinking about myself as a psychoanalyst. And it’s a lot about my history, the history in the family, the history of trauma, how that lives in me.

One thing that a mentor told me once is that you’re a psychoanalyst everywhere, and I feel that a lot, it’s the way that I think in the world. Now, I think it helps my politics, it helps me interpersonally, and it helps me in my work. But I think what I’m excited about in my work, what’s been a kind of generative area for me, is groups and place, and that’s a lot of what my paper is about. What does it mean to be in community as a psychoanalyst versus what does it mean to be a psychoanalyst in a private setting?

And when I say institutional, I mean that I’ve seen that some people– we take training, and then we just live in this little world of private practice. And I’m very interested in not just staying in that little private practice world, even though I love my work with my patients.

But, I feel like it’s about the intersection of the social and psychoanalysis. And that’s where I was thinking about your work, Luz, and how just the little I know about art and social practice, is that there’s something very similar there, like about the intersection of something with something. So how do we understand these spaces that we’re all in? And I think yours is from, like, an artistic aesthetic, but also a historical perspective. I see a lot about that in your work. So with psychoanalysis, too, you take a place, and you try to deeply understand a place, but I’m interested in the places where most people are receiving help.

Right now, I’m involved with a community psychoanalysis project that I’ve been part of since the beginning of the training. And it’s an emergent project of psychoanalysis. It’s about community and psychoanalysis and the intersection of the two. I first did a project that was at an agency that did work with refugees and asylum seekers. And what’s different about this is that instead of a person being my training case, because we talk about cases in my field, the whole place is my case, and also I’m their case. I meet with a group of people who are in community mental health, people who are very analytic but have not had formal psychoanalytic training. We dissect and talk about the intersection of what’s happening in that place. And the social, what’s happening socially about immigration and refugees. My colleague and I did what’s called a “case conference,” where the therapists at the agency present their cases to my colleague and I, and then we present that to a group of people. So it’s like groups thinking about groups.

Luz: Yeah, that’s really cool. I can already see a lot of places of overlap in our work. I’m also really interested in place; in site-specific, place based work, and work that is durational. I think what you’re doing is really specific to that place in that time, to being in that time together. Yeah, and that’s not something you can recreate– that’s really interesting to me.

Judy: It’s a moment, yeah.

Luz: What you’re trying to do with that moment is really interesting.

Judy: It’s also the fact that it’s a historical moment that enters into it for me. And now I’m doing a project that’s fascinating– So we’re not in a mental health setting. I’m co-facilitating a group at the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office. These are the people who try to represent people who have no money and who are imprisoned, and try to get them out.

Luz: So what is your role there as someone who is from the mental health side of things?

Judy: Right? Excellent question. Really, just to try and help these people with their trauma and to create some kind of space for them. And it’s emergent. With the community psychoanalysis we never come in with a prescribed idea, like dropping psychoanalysis into a place. Instead, we co-create something. It’s early in the project now, but we’re trying to see what these folks need to help them do their work, to help them with whatever their themes are. So we don’t have anything prescribed that we do except that we hold a space.

I’m excited about the intersection of psychoanalysis and the world. I’m also involved with radicals in psychoanalysis and many of us have been talking about Palestine. I’m going to be starting a study group with other people who are in mental health about Palestine.

Luz: That’s good. I’ve been thinking lately that we need to be creating in-person spaces to meet and talk about everything instead of like, pushing it down and trying to just do our life. Because that’s dangerous. We need to talk to each other. In terms of organizing, too, it seems like no one knows where to start, and everything is so connected. And the way that movements have started historically is people being in the same place talking to each other.

Judy: Yes, yes. I’m thinking about how my colleague and I are starting this group. We trained together, and some of these issues came up, you know, and we were realizing– after October 7, and with the bombing in Gaza, like everybody we were talking to was saying, I don’t know how to have these conversations. There’s also something about positionality in this, like, I’m having it as a Jew, she’s having it as not a Jewish person. And, you know, we’re talking about politics now, but I think it’s connected to psychoanalysis, as I think it has to do with thoughtful and deep conversations, and how do we– it’s hard to not want to just shut out or even get so angry at what other people say and try to have a dialogue.

Luz: Well, it sounds like what you’re saying is that you’re trying to hold a container for people, right? And that is also an area of overlap in our work. I think we use a lot of the same words in our work and I’m interested in what they mean for both of us. We use the word container a lot in my MFA program– we talk about it as a structure or framework to share your work with the world. I’ve been thinking about research that I’ve done as part of my practice, and research can be, like, the way that I see and feel and do the world, like my note taking practice for example. So, it’s about creating or finding a container that already exists in the world to plug that stuff into so that I’m actually sharing it with others instead of like, putting it back into the internal loop of my own practice.

Judy: Oh, wow, that is really powerful when I hear you say that. That’s a powerful overlap to have a container.

Luz: Another thing our practices have in common is working in an emergent way. Adrienne Maree Brown writes about the work of emergent strategy… For social practice and socially engaged artists who do projects in communities they don’t belong to, I think it’s the only method that makes sense and feels ethical. To be able to come in without your own expectations or a problem that you perceived that maybe isn’t actually there, it’s really important in the work, I think.

Judy: Exactly. There’s so much overlap here from what you’re saying. You’re not coming in with anything. A lot of these projects are happening because someone who works there wants a deep thinking space to happen there. One thing that we have been discussing as we try to write theory about this work is that everyone is a teacher and everyone is a learner. Even as therapists and analysts, we’re having an encounter with someone or some place. It’s not that I’m this smart analyst and I know everything about mental health and I’m going to make you better. We’re trying to have a relationship and an encounter, a reflective space.

Luz: That’s interesting because I think that is different from what I thought psychoanalysis was for. When I think about that work, I do think that I’m going to a person who has trained in this, in something that I don’t know and that they are going to show me some unknown or hidden part of myself, right?

Judy: Well, those are the origins, and I think we do– I do, still believe in the unconscious, and I do believe that we don’t know about some things for a reason. I think that we have lots of good reasons to not know a lot of things. And that doesn’t mean we have to bring every single thing we ever felt to consciousness, but I think psychoanalysis is based on the unconscious, but there’s also a legacy of really negative things in psychoanalysis. We’re in a period of trying to liberate and change it, that’s what I’m interested in. For all of his problems, Freud did have a really powerful idea that we have an unconscious, and that sometimes when we don’t understand how we behave in the world, there may be some information there that we don’t know about. That basic thing that can be helpful, but–

Luz: But it sounds like you’re saying that it’s more about creating a relationship and maintaining that relationship, and then seeing what comes from that. That’s really interesting, because I don’t know that I previously understood that this is what your work is about.

Judy: Yeah, that’s where the container comes in. It’s a very protected kind of specific relationship, and it has what we call a frame, which means that we always meet at a certain time, and that someone pays me whatever we decide on. That’s a frame, that’s a container, that’s a space that I reserve for my patients, that time that our minds are together. And we have an encounter.

One really basic thing is that what I’ve learned, and it’s in my paper, is that a pause, anywhere, is a gift. That’s the title of my paper, “the overfull object: history, place and the gift of a pause.”

Luz: What does an object mean in your work?

Judy: Some of the terminology we use is that we take things in and they become our internal objects. So, for me, I have an internal object of mother and father inside me from my parents, so something with that. It’s something we internalize and we call it an object, but I think I also play with it in my paper title.

Luz: When you say that an object is “full,” or “overfull,” what does that mean?

Judy: It’s something that is saturated. So these places I talked about, they’re saturated, there’s so much going on in them. If a person is overfull, it’s very difficult to think and feel and pause because you’re trying to sort out what’s yours. What are my own feelings and what has been kind of put into me? With trauma, what do we hold inside that comes from others, that is in a way put into us, from a mother, father, caregiver, the culture.

Luz: I remember the last time you visited Portland, we were talking about the overfull object a little bit. You were saying for you that a lot of it is with your parents, and specifically your mother, and that there was something for her that was already overfull and then that spilled over and became overfilled for you. I think that’s a really interesting framework, of thinking about not just intergenerational trauma, (although a lot of it is for our family with the Holocaust and stuff,) but like the stuff that fills us. I’m picturing it like you have a box for this and a box for that inside of you, and that because of what happened to your parents and their parents and so far back, that those boxes can get filled up, overfilled.

Judy: Yeah, it’s a beautiful image to work with there. It’s helpful to have an image like that, and a metaphor. But I think everyone has trauma on some level, like there’s big trauma and there’s little trauma, but every human has some trauma. Traumatized parents have a hard time metabolizing things. There isn’t a digestion, it just gets passed around, and then people respond from that place. That’s a lot of what my paper is about.

Luz: I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately.

Judy: I could talk about this for, like, five hours with you.

Luz: Well, I was just gonna say I’ve actually been thinking about what you were just talking about in regards to how American Jews, and Zionist Jews in particular, have been responding to the crisis in Palestine–

Judy: Total trauma response.

Luz: Yeah, there’s so much there that is not being said when someone posts a comment. When I read a comment, I’m just like, what the fuck is wrong with you? And then I’m like, Oh, I know what’s wrong with you, you have like, three generations of unprocessed trauma.

But the thing is, that is literally happening to Palestinians right now. We’re talking about stuff that, generations later, is still going to be present for their descendants. When I think about my grandparents and great grandparents on your side of the family– how your dad and his brother got out, but his parents didn’t. And then I think about how your childhood was and how you talk with your cousins and your sister about how your parents didn’t talk about anything, because they were so traumatized. So that got passed down to you as some kind of unprocessed baggage that you have to hold. And then, you know, you break that cycle, you and your sister and cousins, I think, by naming it and talking about it. And we break that cycle by continuing to talk about it today, but it’s still there three generations later, in your body and in your life. So I’m thinking about that connection, and how some people haven’t examined that for themselves and are having, well, what you’re saying, trauma reactions to this.

Judy: I think the Holocaust has been weaponized, but it’s also an internal response that people are terrified, and for many Jewish people, like our family, we have the Holocaust as part of our origins. The trauma is in us. The state of Israel was founded with the expulsion of 750,000 Palestinians 75 years ago. Children in Gaza now have lived through 4 wars. Israel is an apartheid state, which in part means that there are different laws for Palestinians and Israelis.

Luz: Right, so it’s almost like taking that analogy that I had back at least three more generations.

Judy: The Nakba, 1948, the catastrophe.

Luz: I’ve seen films where Palestinian youth are talking to their grandparents about that. They ask, “will you ever get to go back to your home?”

Judy: And one interesting thing that I think I’ve learned in psychoanalysis that I’m seeing now is that people can’t think when there’s trauma, and actually, being able to think is very important. The thinking function leaves, and this is where you have these people just reacting in these crazy ways. And you can’t really have a conversation, right? That’s where the pause comes in. First, you need to pause. How do you feel about this? People can’t think, thinking is shut down. And it’s dangerous when thinking is shut down.

Luz: What I think is so dangerous right now is that you don’t know what someone is acting out of, or reacting out of, when you are engaging online with them, because you don’t know them and you can’t see them. And so, you know, you do get like these reactionary comments. Every interaction is so charged with all of that. And there’s no place for it in the container of social media, of a corporation.

Judy: That’s so interesting. Also, just like social media as a container– is it a container? It doesn’t feel like a container right now.

Luz: But we’ve been socialized to think of it as that, yeah.

Judy: And Palestinians are also asking us to keep posting, keep posting, keep posting. You know It’s how we’re bearing witness right now, which is crazy.

Luz: It’s the first, I mean, as far as I know, the first time that we are witnessing genocide in real time on social media. That’s insane. I don’t even know what to do with that as a fact.

Judy: Yeah, I’m thinking about my patients– some people are talking about this, and some people are not talking about this. And it’s fascinating to me, where it enters the space. Whether we are talking about it or not, it is there.

Luz: I’m thinking about how deep into this late stage capitalism dystopia we’re in. How we’ve all been just barely getting by for like, a decade, at least. We’re already in the pandemic, we’re already so entrenched in things not being okay and and still continuing because we just have to, apparently. Because the world won’t stop for a pandemic, so the world won’t stop for us needing a pause. If you take a pause, there’s a very real threat of falling behind and suffering because you need to work to survive.

I think about growing up as a child of a family of Holocaust survivors and nonsurvivors, and the thing that was always in my mind was like, Okay, well, what, what would you have done if it was happening in your life? What would you have done if you were not a Jew? And it was not happening to you or your family? And that was always the question, and I always thought I would have fought back, and it actually takes so much courage to do that right now. And obviously, we’re also in a really different time.

Judy: Well, it takes courage, and there’s the silencing. There’s a lot of very intense silencing of the standing up, but millions are in the streets. I mean, we haven’t seen protests this big in decades, since the Iraq War. There’s millions of people in the streets all over the world. So, this is positive.

When you say there’s no pause because we have to keep going, that’s external, right? There’s external factors, but I’m also talking about a pause inside that we can find. I think that to me, a gift of psychoanalysis was finding that. And I don’t do it all the time, you know, I have to still keep reminding myself all the time to do it, but that I can find a pause inside me.

Luz: I think the external stuff has to give way for there to be time and actual space to do that internal work though.

Judy: I know, right, and that’s psychoanalysis, which isn’t accessible to everyone. Even just therapy isn’t accessible to everyone. With these projects I’ve been talking about, it’s exactly that– you work in an agency, you have this incredibly intense caseload, there’s trauma all around you, there’s pressures of work, there’s a demand on your time for more and more and more work, because this is how late stage capitalism is in every workplace. They call it the nonprofit industrial complex. Even in a nonprofit, even in a place that serves people, even in schools, with teachers, it’s present. So, what if people can have a group that meets even once every two weeks for an hour, where they get to sit and reflect and have a reflective space? That’s a pause. And that’s kind of my passion is to find a way to bring that, if people want that. But first, do people want it? It comes back to emergent work.

Luz: I think we know that collectively, we do need a pause right now.

Judy: And a reflective space, yeah, time to think and feel. And that’s not built in, in this culture, in this system. It’s not something that’s honored. But on your dad’s side of the family, your grandmother is really dedicated to this. Like, wait, let’s take a moment and acknowledge that this is someone’s life, their birthday, whatever it is, you know. I think ritual also gives pause, which is a beautiful thing, I love ritual. I wish I did more of it.

Luz: Part of my work that I really have been really appreciative of the last few years is how conceptual it can be, and how, like, deep theory it can get. That you can change the way that you frame something intellectually, and that can have kind of a ripple effect in other parts of your life. You can look back at something you did in the past that may not have felt meaningful enough then and reclaim it as your work now, and that’s really helpful. I often think of Sister Corita Kent’s 10 Rules, and one of them is, and I’m paraphrasing, “You cannot create and analyze at the same time. They are different processes.” I think about that one a lot.

Judy: I’m writing that down, it just feels like it applies to my work, “you cannot create and analyze at the same time, they are different processes.”

Luz: Yeah, and so I think, you can create a framework for a pause or create the space that it is your work to create, and later, when you’re writing about it, you can hold the way that that can be framed as a ritual, actually, because it is something that you’re coming back to over and over again. I think part of the thing that makes it a ritual is doing the same thing in the same place at a certain time. The thing itself, the meaning and the time together itself is a ritual. It’s not ritualistic and loaded with lore and specific aesthetics necessarily, but it is a ritual. And I think of it that way, in a conceptual framework, the work of repeating an event or even a one time thing in one place and time, like we were talking about in the beginning. I think that a moment in time can be a ritual. An encounter can be a ritual.

Judy: Because the container makes it a ritual. Yeah, that’s so beautiful. I always learn when I talk with you. I was thinking of the pandemic recently because the container changed. It was this big regroup, you know, and some people are back in their offices. I’m there less, but, you know, I’m still doing this ritual. I’m still finding a space inside myself to do this work with my patients, you know, whether it’s on Zoom or on the phone. The container is still there. It’s me, I’m the container. But there’s something about the space between us; you know, our voices.

Judy Blumenfeld (she/her) is a licensed marriage and family therapist and psychoanalyst. She locates herself as an activist in movements for social justice in all parts of her life and work. She is a native New Yorker and lives and works in Oakland, California. Judy is Luz’s mom.

Luz Blumenfeld (they/them) is a transdisciplinary artist, writer, and educator. Third generation from Oakland, California, they currently live and work in Portland, OR where they are in their final year of the MFA in Art + Social Practice program at Portland State University. This summer, they published their first book, More and More Often, a collection of notes and pictures. You can see more of their work here. Luz is also Judy’s daughter (there’s no good gender neutral term for being someone’s adult child).