Identity and Spaces

January 9, 2021

Text by Brianna Ortega with Soheila Azadi

“My Muslim audience is the most challenging audience I have and they respond to my work differently based on if or how familiar they are with art and American culture.”

I chose to interview Soheila due to my own background of creating work about women surfers or surf culture in general, which is a specific culture and identity outside of the art world. Soheila explores the identity of Muslim women in her work. She explores this personal and cultural identity that comes along with social norms and constructs, in relationship to places, within which she questions power. In this interview, Soheila opens up about navigating different worlds, considering private and public, how her work has changed over time since moving from Iran, how she navigates talking about her work to audiences not familiar with Islam, and the stereotyping of religion and spirituality in societies.

Brianna Ortega: How has your work changed over time since leaving Iran and how has living in the U.S. impacted your work?

Soheila Azadi: My work has changed a lot. That is a good question. I realize over time it is changing even more. When you live in a place longer you realize that to some degree you are cutting ties from your homeland. It’s been happening to me especially in recent years, maybe two to three years since having my child. I feel like I am much more connected to the culture here than I am to my culture back home. Learning the American humor was part of it. I think it was in graduate school when I started incorporating American humor in my work. Our humor is very dark and very offensive to americans. The more I stay here the more I connect to pop culture which you can see traces of in my work.

In the beginning when I started working, I was really angry and the art form was a way for me to get all the anger out, but at this point in my life I am not angry anymore and I have come to peace with myself, my home country and my identity. That is why how I make work is very different from how I made work at the beginning.

Brianna: Can you give an example of how you work differently now?

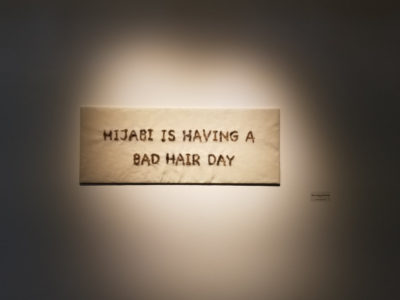

Soheila: Now I think about my Muslim born identity in a more open minded way. It is to accept it, acknowledge it and celebrate it. Whereas before I was angry—asking myself questions like why I was born in that country and thinking about how it affected my childhood and teenage years; I was angry all the time. Versus now, I am just celebrating it. For example the Hijabi is Having a Bad Hair Day piece is a celebration of being a Muslim. It is a celebration of an identity, of which a huge part ties to religion.

Brianna: How has your audience changed over time in your work and how do different audiences respond to your work?

Soheila: I moved from Chicago to Portland. And then that automatically brought a different audience to my work. My last solo exhibition was at George Fox University, which is a Christian university. It was very interesting for me to get that invitation and thinking that there were

conservative Christian people viewing my work, which is a celebration of another religion…it was fascinating to me. That was a huge change. That could be the most different audience I have ever had. But, other than that, most of my work has been in galleries and in festivals and universities, so all of them were in these sorts of safe bubbles.

The other audience I have is the Muslim audience, to whom I recently have started opening my work. Before I was hesitant and wasn’t sure if I was ready to receive any criticism from them, because again my work is sitting on this very fine line that becomes either appropriated or not, or becomes offensive or not. If you are not familiar with American culture and humor, there are parts of my work that may come off as offensive. With the Hijabi is Having a Bad Hair Day project, I’ve had friends come to my house and I have to explain what it means from the beginning, like when someone is having a bad hair day. It is very different from what they think. So my Muslim audience is the most challenging audience I have and they respond to my work differently based on if or how familiar they are with art and American culture. Some of them are very excited that I am taking on this role to represent them. And some are worried that I might represent a very romanticized version of Muslim women, espeically those who have not come to peace with their own Muslim identity. So it is very mixed, but I would say the most diverse audience I have is my Muslim audience.

Brianna: You mentioned in your lecture at King School Museum of Contemporary Art (KSMoCA) that you don’t really talk about your work in Iran?

Soheila: I don’t. Even with family…I just make it very brief if anyone asks and say that it’s on human rights. But then I don’t tell them from which dimension I deal with this issue. The religion subject is very touchy especially back home, because of restrictions with the government and because of different religious views within Iran. Not everybody thinks they are Muslim because they were born Muslim, not everyone is practicing and there are many people who do practice and in different ways, like Christianity. But because of government restrictions, they are not allowed to express that. Just like here, you cannot assume just because someone was born Christian that they practice that. So because it’s such a hush hush subject back home, it is very touchy and I don’t talk about it. They ask me and know I am an artist, but they don’t know my work. I usually disable my website when I go home just to be safe.

Brianna: Have you ever made work about that experience?

Soheila: No, but that is a good idea. It’s this cloud that I feel I am not ready to touch and deal with for now. That is the question that regularly comes up in discussion in regards to my practice. Would you ever have a show in Iran? And I would say, yes I am hoping that I would, but would I be producing similar work that I am producing here? I don’t know, I am not sure.

Brianna: How does it make you feel that you can’t talk about your work when you go back there?

Soheila: I feel like in general going to Iran, I try to be invisible in every aspect. It is such a male-dominated culture that I regularly get disappointed. So to not be disappointed as much, I try to keep it all in and try to stay within the family and celebrate being with them. Something as simple as buying a bag of chips is challenging for me when I go to Iran. And so when it comes to my practice, first of all, most people don’t even want to acknowledge that you have accomplished anything. If they ask me questions, men especially, when they ask me questions, when I answer, so many of them say, “Oh maybe you don’t know, we should ask your husband.” Not in regards to my practice, but in general. So for me to have a concrete conversation with these types of people is not something I welcome. I have been preventing it.

Even there was a point where we were mostly women and talking about feminism and all of a sudden there was a guy there. He started talking about feminism and I had to tell him that feminism is not what he thinks it is. And I talked about different waves of feminism. He was one of the few guys in Iran that had the tolerance to sit down and talk. But there are very few out there so I am not ready to deal with it.

Brianna: I feel like I can relate to the conversation you are bringing up about hiding parts of ourselves due to stereotypes. People always think there is one type of person within a box that they are creating. And I don’t always want to open up and engage with people with my personal spiritual beliefs or other beliefs because there are a lot of misconceptions and stereotypes. I feel like I don’t want to always jump into their stereotype, because a lot of people are closed and not ready to hear about someone else’s experience. Like you’re saying—it’s like this cloud and I don’t always want to engage with that.

Soheila: Exactly, and it is so much heavier in the arts community. I have had friends whose work dealt with Christianity; one of them received so much hateful criticism. Her work was on the intersection between Christianity and obsessiveness. Her work is very interesting, but in graduate school, she was getting many hateful comments. I can see what you are saying. To be cool, that means to not believe in anything.

Brianna: Interesting. I had a conversation recently with someone in Portland who said they loved India. And I asked why did you love India? They said because they had spirituality in all they did in India and that they were really drawn to that, that it was interesting to be around since Portland is not very religious at all. I think ultimately people have a fear of believing in something that is greater than them, but then they are drawn to that at the same time.

Soheila: Double standard.

Brianna: Maybe I should include all of this in the interview. It’s interesting to talk about.

Soheila: Why not? I personally don’t identify as a Muslim and don’t practice it and believe in it, but I have no issues with who believes in it. Because I lived a life where I believed in it and now I can recognize how I felt before as a non-believer. It gives me relief to still be connected to people who do believe and be connected to people who don’t believe.

Brianna: After watching the KSMoCA interview with you, I was thinking about men giving women access to spaces and women giving women access to spaces. Do you have any thoughts on this and in reference to your work?

Soheila: That is very interesting. The spaces for example—the female only taxis are a systematic way of separating people based on their sex which is organized by men in society, and then there are women who are for it within the system and support that. Let’s say that is the creation of men—the gendered space, versus the space of female only parties that women create for themselves.

I think I deal less with the ones that are systematic in a way. I feel like they are all systematic, but I deal with the ones that are invisible. I deal with the ones that women create as a way to liberate themselves. I think about female-only parties. Most of my projects deal with that—almost all of them. Like the creation of craft as a result of these separations. The craft could happen either way. Unveiling is something I would say is the thing that happens in female space that they create for themselves. The unveiling part is the most challenging aspect for me to deal with in my practice because I did deal with it shortly in my work Bazar, where there was a tent within a tent and in the smaller tent there was a Hijabi woman in that community and she was unveiled and only women were allowed to enter that smaller ten. Other than that it has been very challenging to deal with that part.

My focus has been more on women creating gendered spaces for themselves as a way to liberate each other. But the truth is: it is men who created those spaces, which is the result of religion. Please keep in mind that I am specifically speaking about Muslim societies such as Iran.

Brianna: How do you think about private versus public space in your work?

Soheila: It is so challenging because for us in the United States, public is public and private is private. There is no confusion. But in Iran and in my work because I deal with those spaces, public at times can be private and private at times could be public. Lines and boundaries are not defined. And especially in Iran because of different ways of thinking—as long as it is a governmental building for example, rules that define the public are rigid and you know you cannot cross them. But, there are restaurants and cafes and places that people go and unveil secretly. So in those spaces, if government officials come, they will be in trouble, but they still do it. Or for example, if you do mountain climbing, you can at times unveil. That’s why I call them semi-private spaces. They are still public. There’s a huge mountain in my city. It’s such a thing to climb it on weekends. It is a public space. But the further you get to the top the less busy it gets, so the government officials have less access to the top. And so those lines between private and public get blurry on top as you climb it and you realize it. People’s veils get looser and looser to the point where people lose their veil. And many people take alcohol with them which is forbidden in Iran and drink it there. So it’s fascinating.

I remember growing up, I had so many questions that I was puzzled by. I didn’t know what was appropriate based on what is private and what is not, and I still struggle with that.

Brianna: I was also interested in your relationship to explaining your work. For example, all of my work is inspired by surf culture so I sometimes have to explain it a lot. So I was wondering how you navigate that.

Soheila: Yeah, I mean there are two things in my work that I have to explain: one is the history and culture of Iran and then the other aspect is specially talking about Muslim women. These two, although they are related, are different. At times depending on my audience, if it is in a university, sometimes I assume that the audience knows a little bit about the history or social construct of Iran. Or knows a little bit about Islam. So I don’t go deep into explaining to them. But there are communities to whom I felt like I had to explain further. You still want to keep it brief to not take away from your presentation time and your work.

But I think the most challenging time I had was talking about these experiences during graduate school. At that time my work was not dealing with what it deals with now. That is one reason why I started doing events and performance art because it is more tangible with people’s bodily experiences. That is why I started, for example, the Bazar project where people came into a semi-private space and paid for different services from Muslim women, like henna, and others. Eventually, I learned about socially engaged art and how there is no limit for the form of the work.

At that time I knew these two forms of making gave me the liberty to talk about experiences and made it much easier.

Brianna: How did you navigate mirroring social realities in some of your past work?

Soheila: At the beginning I was doing that more, but then I started questioning all the separations. At that time, my work was mirroring those separations and I was, in a way, creating exactly what I was questioning and criticizing. There was a point where I realized, if I am creating the same issue, how am I helping the cause? I was reading so many feminist theories and I realized one of the things they think about constantly is how by recreating an issue you are not helping the issue.

That is why I stopped creating works that were separating people based on sex and rather I focused later on the result of these spaces—the material that could come out and the conversations rather than recreating these spaces.

in collaboration with Zohreh Pasandi, Shahnaz Azad, Iraj Azadi; Chicago, 2015

Brianna: What is one of your favorite memories of how someone has interacted with your work?

Soheila: Grow Some Balls was a part of my thesis exhibition. People could sit on it and swing and there were balls underneath it. It was poking fun at the language we use that is problematic and gendered, as in “grow some balls.” The funny thing is that only men physically interacted with the piece. I thought, I am going to give the people the chance to sit on balls, be elevated and gain some sort of power in a playful way. But men who actually have balls sat on it and rode it. Unfortunately, you see that everywhere—women are more shy in galleries to interact with pieces and men have the confidence to interact. That is the only one that comes to my mind.

Soheila Azadi is an interdisciplinary practicing artist, educator, writer, and a mother based in Iran and Portland. She narrates stories of lived experiences of Muslim women of color visually and verbally. Her practice is concerned with political weight within the context of historic marginalization based on gender in different cultures. Drawing from the expansive conceptual terrain of architecture and its relationship to religion, she thinks through how segregated spaces that are the results of religion utilize a framework for creativity.

www.soheilaazadi.com

Brianna Ortega is an artist, educator, writer, and surfer based on the Oregon coast. Through embedding herself in surf culture, she uses art as a tool to explore the relationship between identity and place through questioning power in social constructs and physical spaces. She engages with topics of gender, race, Otherness, place, and the in-between spaces of identity. Her work is multidisciplinary, spanning across performance, publishing, organizing, video and facilitation. www.briandthesea.com