Category: Essays

Tia Kramer: Scores for Creative Exercise

Text by Tia Kramer

I Remember Well: Recreation and Spiritual Striving

Text by Nola Hanson

By Nola Hanson

MRI WRIST WITHOUT IV CONTRAST LEFT ‐ Final result ﴾03/21/2019 11:36 AM EDT﴿

3.26.2019

I’m in Waukesha, Wisconsin for my grandmother’s funeral. I’m playing basketball at the YMCA.

Older people walk in circles on the track above the court. A man stops, leans over the railing with his forearms and looks down at me.

I’m trying to hit a spot that hasn’t changed since the first time I aimed for it in the same gym,

at age five, when I looked like this:

—

My mom signed me up for basketball camp; she bought me a heather gray tank top to practice in; I remember the adhesive strip that ran down the right side of it.

S

S

S

S

S

S

S

I didn’t want to take it off, I thought it was part of the uniform.

—

MRI WRIST WITHOUT IV CONTRAST RIGHT ‐ Final result ﴾04/20/2018 1:08 PM EDT﴿

—

I remember the wood, nylon nets, the orange rims. The mesh jerseys we used for scrimmages. The silver whistle that hung from from a black braided rope on my coaches neck.

During games I’d stick my tongue out and lick; from the heel of my palm to the tip of my middle finger. I’d lift my feet up under me, and slide my hands over the rubber soles of my sneakers to remove the dust, so I could hear them squeak. I had to stop after a teammate saw me, and said that’s the same thing as licking the floor and I couldn’t tell her: I know.

—

At Sunday school when I asked what heaven is they said picture your favorite place;

it’s like going there and never having to leave. I imagined the court I’d seen at the Milwaukee Bucks game, but all of the people were gone except me.

—

I remember being six, sitting on a 5th graders lap in the auditorium. Everyone sat in the dark and faced the same direction, reading lyrics to Christmas songs that were printed on transparencies and projected onto a screen. When he found out I wasn’t male assigned at birth he screamed, pushed me off, and said he was scared of me.

“My body was given back to me, sprawled out, distorted, recolored, clad in mourning…” (Fanon, 259)

I felt like I lost a game I didn’t agree to play in the first place.

—

Recently, back home, my mom and I stood in my sisters kitchen. She asked did I remember what I said to her at the mall the day before my grandfather’s funeral?

No, I forgot.

She said, “You looked at me with tears in your eyes and said ‘What the fuck am I supposed to wear?’”

Which meant, of course “Who am I supposed to be?”

“It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” (Du Bois, 2)

—

My grandfather, Leif, was the star quarterback on his football team in college, and after that, a World War 2 bomber pilot.

He was the person who taught me how to dribble. I remember his sun spotted hands floating over my head in the driveway.

We would go to Swing Time Driving Range and hit balls together. One of the last times we went, he fell and hit his back, smack dab in the middle of a wooden divider that separated the squares of fake grass.

He died when I was sixteen, in his living room with his mouth open next to an American flag folded up in a glass case, and a model of a Boeing B-17 airplane.

MRI WRIST WITHOUT IV CONTRAST RIGHT ‐ Final result ﴾02/04/2017 12:45 PM EST﴿

3.28.19

My cousin Nels eats Mexican food out of a plastic rust colored container. His spoon has a molded rubber grip at the end of it, and he drinks his Coke out of a big cup with a straw and a lid that twists off.

He says he pictures me skipping rope. The rhythm of it, the sound like a rubber band under my feet. He says he remembers the feeling and when he thinks of me he feels it in his body.

He says the last time my grandmother came to see him, she didn’t even make it around the corner to look at him. She leaned over the back of his hospital bed and kissed him on the top of the head.

“The more one forgets himself… the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself. What is called self-actualization is not an attainable aim at all, for the simple reason that the more one would strive for it, the more he would miss it.” (Frankl, 133)

4.17. 2019

I’m sitting at a table with Takahiro Yamamoto, and 10 undergraduate students.

He says, “Forgetting is important.”

MRI WRIST WITHOUT IV CONTRAST RIGHT ‐ Final result ﴾04/20/2018 1:08 PM EST﴿

7.12.16

While hitting the heavy bag at the New Bed Stuy Boxing Gym– home of former world champions Riddick Bowe and Mark Breland– I tear a ligament called the Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex. They call it the meniscus of the wrist. I get a cortisone injection and train on it for two years.

MRI WRIST WITHOUT IV CONTRAST RIGHT ‐ Final result ﴾02/04/2017 12:45 PM EST﴿

—

My friend and I are walking in Chinatown. We go into a Vietnamese restaurant. She swore there used to be fish tanks here, or is she going crazy? The waiter says yes, there were. They renovated a year ago and made room for more tables. When we order, the waiter calls her sir.

She says that when she started taking T blockers and estrogen, she had this feeling, like: oh, so this is what it’s like to be a person.

—

XR WRIST 3+ VW LEFT ﴾XR WRIST PA LATERAL AND OBLIQUE LEFT﴿ ‐ Final result ﴾02/07/2019 4:16 PM EST﴿

4.16.2019

My new roommate tells me she saw her ex for the first time in 15 years: “She was such a cute dyke,” she says, “…now he’s just an old man.”

- Works cited:

- Frankl, Viktor E. Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984. Print.

- Du, Bois W. E. B, and Brent H. Edwards. The Souls of Black Folk. Oxford [England: Oxford University Press, 2007. Print.

- Merton, Thomas. Zen and the Birds of Appetite. [New Directions], 1968. Print.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. New York : Grove Weidenfeld, 1991. Print.

Where I Play

Text by Roz Crews

By Roz Crews

I’m a “lonely only” and when I was a kid, I spent a lot of time by myself or with the neighbors. I knew that playtime meant I could choose to be alone floating through my thoughts or I could be with other kids, developing communication and negotiation skills. Both options were fun, but they required different kinds of mental energy. Playing together was difficult, and it felt like learning, which felt like work. Slow and painful, but then I grew three inches in one year.

I found freedom in privacy, and I frequently experienced self-doubt when I played in public space. All of the kids my age who lived in the neighborhood identified as boys, and they loved baseball, building stuff using power tools, video games, and skateboarding. Sometimes I ran alongside their skateboards pretending I was on a skateboard, but I preferred imagining doll weddings, catering fake events with real food, choreographing music videos for popular songs, searching for fossils in the creek, and narrating the lives of stuffed animals.

One of our greatest collaborations was called “House in the Trees,” and the project combined and benefited from our diverse interests: we built a series of structures between two small magnolia trees on the edge of our property, ate meals there, hosted group discussions, and used it as a backdrop for our life together. We barely left the neighborhood during playtime, and if we did go on an excursion, we usually went to a local park.

In the 1990s, Westside Park, the largest city-owned park in Gainesville, Florida had a few metal climbing structures including classics like a slide and a swing set, but it also had a really simple play object shaped like a spider. It was hard to climb up the metal spider legs, but if you could, you sat upon the spider’s back. Thinking about it now, I’m reminded of Louise Bourgeois’ spider sculptures:

“The spider—why the spider? Because my best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and as useful as a spider.”

—Louise Bourgeois

I felt insecure near the spider. I sat heavy at the juncture where its leg met the ground, and I felt incapable in contrast to my peers who could effortlessly slither up the slender metal limbs. This object stood in the park like a sculpture in a public garden, and I wanted to spend time with it by myself—to appreciate its beauty and persistently practice climbing its legs protected from the gaze of other people. I wish Louise Bourgeois was my grandma, and she could lift me atop the spider where she’d whisper into my ear: “You are patient and reasonable, dainty and subtle, completely indispensable.”

In 2009, the park was renamed Albert “Ray” Massey Westside Park and Recreation Center in recognition of a man who is known regionally as the “Grandfather of Recreation.” In a news article about the renaming, Massey is said to have made recreation possible in the city of Gainesville. This makes me wonder: What does it mean to recreate?

I hate the idea that a park or a playground or a structure or a person would be designed and designated as the facilitator of play.

If it were up to the spider, I’d be alone and crying, destined to a life in the mulch. Eventually, I would create a habitat beneath where I could tunnel into a crystal cavern in the Florida aquifer, but that would take years. At some point during my childhood, the spider was removed, and all the simple metal sculptures were replaced with plastic slides and coated metal walkways with pictures of frogs and pirate swords emblazoned on the ship facades. This type of aesthetics for a playground are pervasive. They function like dictators of play. When I was younger, I yearned for these brightly colored plastic playscapes because they were clean and bright and told me what to do.

In contrast to the plastic play utopias that started to appear all around me in the 1990s, there was an incredible, free-standing wooden world called Kidspace designed by famous playground architect Robert Leathers. On special occasions, I would drive fifteen minutes with the neighbors to visit the playground, stopping to get Subway sandwiches along the way. My neighbor’s mom seemed to like taking us there—maybe it was an escape from reality for her, too.

In 1987, parent volunteers from a local elementary school raised $48,000 to build Kidspace. After purchasing supplies and architectural plans, members of the community came together to build the playground in only four days. It covered 15,000 square feet of a formerly empty field behind the school, and it included “a haunted house, boardwalks leading to suspended networks of automobile tires, to rope catwalks, to parallel bars, to slides. There [was] an amphitheater with a stage, a wooden car, a rocket ship, even—something special for Gainesville kids—a big wooden alligator.” After school hours, the park was open to the public.

All of Leathers’ playgrounds are built by “community volunteers,” usually the parents of the kids who use them, and in this case, a representative from Leathers’ architectural firm in Ithaca, NY came to the site to collect ideas from students about what they wanted to see in their playground. The kids suggested: “pretend go-car shark car,” “a robot that talks,” and “a fish sumdareem (submarine) that goes underwater that kids can get in and see fish and sea animals with 5 windows.” None of those things made it into the finished park, but maybe the kids felt a sense of ownership anyway as a result of this process. After twenty years, the playground was dismantled when it was determined that the elaborate wooden structure was leaching arsenic into the soil.

Apparently, Robert Leathers used to wear a red T-shirt with the message, WE BUILT IT TOGETHER. When I think about the process the parents must have gone through to make this playground a reality, I’m impressed by the collaborative spirit and I see their smiling faces as they hammered the wood together, but I also think about the privilege they had to volunteer their time fundraising and building. I’m not aware of a project like this existing on the east side of Gainesville where the families at the time were mostly working class. When I traveled to Kidspace, I could tell this structure wasn’t just a sculpture, it was infused with community care and consideration, and it was a platform where we as kids could design our own ideas and experiences—an opportunity the ordinary, city-funded playgrounds didn’t afford.

When I was sixteen, a veil was lifted and I realized the amount of production adults require in fostering and maintaining play in plastic playground environments. I was hired as a “play leader” at O2B Kids, an Edutainment Company that offers programs for children 0 to 13 years old. As a play leader, I wore what all the play leaders wore: khaki pants and a branded purple t-shirt. I had a pixie haircut, and once a kid asked me, “If you’re a girl, why do you have short hair?” I said it was because I am a princess, and every real princess has short hair. News got around, and I reveled in my new “Neighborhood Time” identity. There were ways to subvert how Neighborhood Time was used, but ultimately, it was a commodified experience contrived by the company, as stated on the O2B Kids website:

Neighborhood Time is a time to give kids a choice of things to do – just as they would experience in a safe neighborhood of yester-year. Choices include a combination of program calendar classes, non-scripted inside and outside play, and counselor led activities. This provides crucial time for your child to explore, make choices, develop friendships and gain independence. Our Counselors are stationed in zones to facilitate safe play.

The entire playscape exists inside a building adjacent to a mall, and I really question the amount of agency children have to make choices in that space.

Everyday at the end of my shift, I crawled through the plastic play tubes, tediously cleaning the shiny interiors. While I wiped away germs, the tubes vibrated with the sounds of dance class (Lil Mama’s Lip Gloss was popping). Not only was I hired to facilitate “Safe Play,” but I was also required to make sure the environment remained sterile for all the kids who came through. I like to think of this place as a painting. All the colors swirl together to make the secure world we want to be in; where the neighborhood is inside and the birthday party is purchased as an all-inclusive deal. But, instead of a birthday party, it’s actually a cruise where you know everyone, even the strangers. The ocean clouds start melting onto everyone’s faces, and there’s nothing you can do about it.

I recently came across a photo of the Noguchi Playscape designed by Isamu Noguchi for Piedmont Park in Atlanta, Georgia. I thought it was a sculpture park, but then I read more about it: it is a playground that was funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts as part of a project with the High Museum, completed in 1976. The Playscape reconceptualizes play equipment as sculpture, obscuring the divisions between fine art, real life, and playtime. Supposedly, Noguchi’s goal in designing playgrounds was to make sculptures a useful part of everyday life. At first, the sculptural quality of the playground made me feel excited because it looked like an enjoyable way to experience art, but later, I started to worry about the dangerous quality of how it might administer play. Noguchi calmed my worry with his vision:

“The playground, instead of telling the child what to do (swing here, climb there), becomes a place for endless exploration, of endless opportunity for changing play.”

—Isamu Noguchi

When I saw the photo of the playground in Atlanta, I was transported back to a moment in 2012 when I visited the Isamu Noguchi Museum in Long Island, NY. During that visit, my friends and I intuitively began shaping our bodies to match the forms of the sculptures. We were freely playing in a very reserved, private yet public space. The photos of the playground got me thinking about my own necessary conditions for play, and I reflected on the publicness of the playground and the privateness of the museum. I searched for images of that trip to New York.

Now I work at an elementary school, and I wonder if the students feel permission to play there. My job at the school is to help organize programming for the King School Museum of Contemporary Art, a contemporary art museum operating inside a functioning K-5 public school. In the museum, there’s a confusing mix of public and private where anyone is invited to visit, but only during school hours and typically with permission of one of the museum administrators. When we invite artists to do workshops with the students, I see everyone playing. The adults are playing with expectations and materials, and the kids look delighted and surprised by what happens in the workshops. It seems like the intergenerational, playful environment is only possible through face-to-face collaboration and conversation. A very serious combination of whimsy and wisdom, freshness and perspective, listening and being heard. More often than not, our team takes cues from the kids about how to “facilitate play.”

Based on this research, I’d like to fill an entire neighborhood with sculptures of giant friendly spiders designed by the kids I work with. Each spider could have an escalator, or an elevator, or a soft sculpture ladder, or even a happy badger with wings that floats you to the spider’s peak if you’re scared. You would have to choose your own adventure, build your own platform, and you would definitely have to let the sculpture tell your story, instead of the other way around. Noguchi’s playgrounds are too beautiful, and they make me nervous—like art is going to take over the world. What I really want is for the world of a painting to spill into reality, and me and the neighbor’s mom could eat subs together in the pebbled floor where falling doesn’t hurt and the vending machine closet comes with unlimited quarters. The birthday party has no adults and kids are screaming and running until they hurt themselves on accident and everyone starts self-policing. If this could happen, WE BUILT IT TOGETHER.

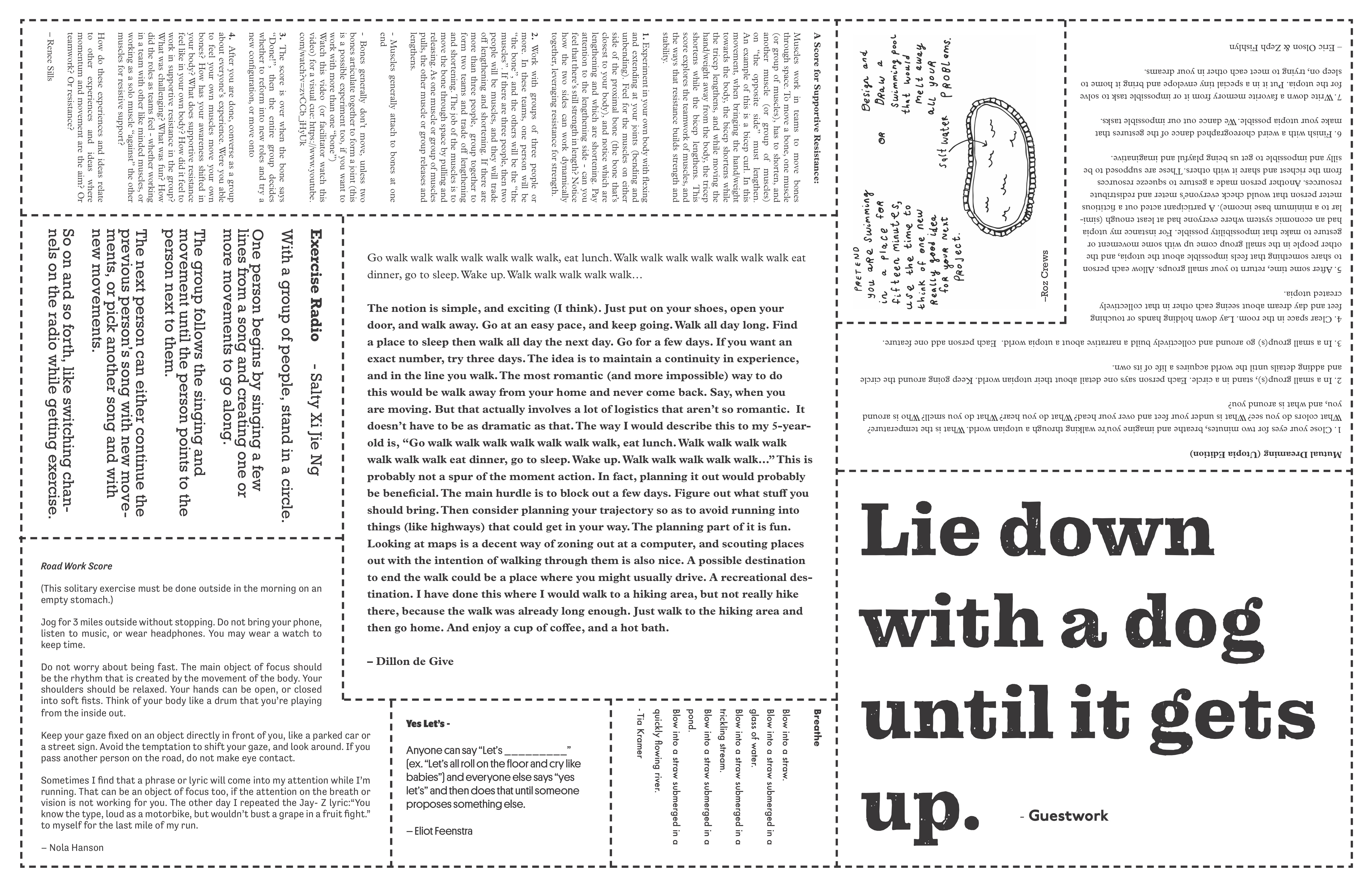

The Radical Imagination Gymnasium

Text by Patricia Vazquez Gomez, Erin Charpentier, Travis Neel, and Zachary Gough

The Radical Imagination Gymnasium is a project by Patricia Vazquez Gomez, Erin Charpentier, Travis Neel, and Zachary Gough.

In the summer 2014, we came across the article Finance as Capital’s Imagination: Reimagining Value and Culture in an Age of Fiction, Capital, and Crisis by Max Haiven. An exploration of the politics of imagination under financialized capitalism, this article raised a lot of questions for us around the ways in which our individual imaginations are dictated by market logic. We’ve essentially lost the ability to value things that aren’t measured by the dollar or monetizable. Furthermore, our imaginations are put to use by developing new ways of capitalizing on resources and exploiting others, rather than resisting such systems and imagining new ways of being together based on mutuality, care, and cooperation.

Further reading brought us to the term radical imagination, which Haiven investigates in several of his books and in his collaborative action/research project, The Radical Imagination Project. In the book Crises of Imagination Crises of Power; Capitalism, Creativity and the Commons, Haiven loosely defines the radical imagination:

“The radical imagination is not a ‘thing’ that we, as individuals, ‘have’. It’s a shared landscape or a commons of possibility that we share as communities. The imagination does not exist purely in the individual mind; it also exists between people, as the result of their attempts to work out how to live and work together.”

That is, the radical imagination is not merely about thinking differently; rather, it is the messy and unorthodox process of thinking together. The concept of the radical imagination, as we use it and borrow from these folks, is largely aspirational; it is a placeholder for the possibilities of collectively reimagining ways of being together in the world.

We began to think of the radical imagination as a group of muscles, weak and underused.

A meeting with our friend and experienced yoga instructor Renee Sills deepened our understanding of anatomy. She explained that muscles only work in teams, and when one muscle is tight, its companion muscle is slack. When one muscle is overused, it causes imbalance and chronic stress. This tightened, overused muscle causes a path of least resistance which dictates movement in its direction. That is, the more you use it, the easier it becomes to use it, and the harder it becomes to reverse the pattern of usage.

Our guiding research question became: What would a workout plan for the ‘radical imagination’ look like? We set out to develop a workout plan for the gymnasium by inviting people to facilitate workshops whose practices already embody the kind of collective imagining that our research was pointing to. The first workout was facilitated by Walidah Imarisha and centered around collective visioning, world building, and science fiction writing on issues of social justice. We designed and facilitated the second workshop with Tamara Lynne, asking participants to collectively (and silently) act out 24 hours in Utopia. Carmen Papalia led the third workout titled “Bodies of Knowledge” exploring notions of radical accessibility and involved crafting a collective definition of open access. The last workout, titled “Yoga for Commonwealth”, was facilitated by Renee Sills and used the form of the yoga class to explore ideas of collective exchange and balance.

These workouts mostly took place in Project Grow’s Port City Gallery with an accompanying exhibition. The exhibition component of this project was accumulative and included influential research, workshop generated material and documentation, as well as staging and equipment for the workshops. Prominent design features included a large scale, vinyl line drawing of a gym floor spanning the wall and floor, standard size CrossFit plyometric boxes reimagined as seating, and a combination weight rack/book shelf.

(Re)create the Radical Imagination Gymnasium

Muscle imbalance continues to feel like an appropriate metaphor for the difficulties of challenging and changing a pattern of behavior or social structure. Within financialized capitalism, we have plenty of opportunities to be rewarded and punished as individuals. What we don’t have is ample opportunity, space, and time to collaborate in the creative process of imagining new ways of being together in the world. For a limited time the Radical Imagination Gymnasium offered space for this work.

We think the radical imagination can be strengthened in the same way that a body is conditioned through incremental exercise; starting small and increasing intensity over time. What if we dedicated two hours every week to collective imagining? Or two hours a day? Could a sustained routine build enough muscle memory to reverse the dominant tendencies of the imagination dictated by market logic? We offer these questions and the proposal to continue exercising the radical imagination.

Guns, Money, Mud, and Play

Text by Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr. and Katie Shook

By Artists Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr. and Katie Shook

Katie and Michael are both artists, and both have practices that involve working with children. So questions about what play is and how play in childhood transfers to adulthood, and to an art practice, are central themes for both of them. Does play in childhood inform one’s interests and pursuits as adults? Does making art for money make art less altruistic? Do violent toys lead to violent behaviours? Is the making of art inherently correlated to play?

Here are some ideas they gathered in response to these questions and others paired with photos drawn from their respective practices and beyond.

PLAY AND ARTMAKING

Children playing in the mud at the Adventure Play Garden, run by the non-profit Portland Free Play. Most people over thirty have memories from childhood of playing outside without adult intrusion. These days, kids don’t get as much time and room to roam, free from an adult agenda.

Katie:

Artmaking really depends on the ability to take the time and space to get into a creative frame of mind. Everyone works differently, but for my practice, I find I need several hours uninterrupted to get anything constructive going. It’s harder for me to get to that place when I’m stressed and feeling under pressure. Creative thinking and the flow state are akin to play, resembling the mindframe that children get into when they are given unstructured play time.

Children deserve time for free play, just as adults have a right to pursue their own intellectual and creative interests.

It can sometimes be hard for adults to see a child’s play time as valuable, and not impose some expectation for learning or performance. There is inherent value in what a child wants to play at according to their own motivation, but the special secret about free play is that children are actually learning and developing on very complex and nuanced levels, often far beyond the outcome of a traditional classroom.

Adults who watch children at play sometimes interpret their actions and intentions inaccurately. We see children’s play through an adult lens, influenced by our history and adult motivations. One way to find out about what kids are playing at is to observe and listen. It can be intrusive to ask kids to explain themselves. And also, I think when kids are in a deep play trance, their experience can be outside of language and putting words to it.

Reflecting on my own experience of art making or being in a state of play, can I put that into words? Would others be able to understand my experience? Sometimes my most satisfying feelings while making art aren’t about ‘fun’ really, but about feeling a drive, or a sense of compulsion. Michael, you’ve used the word ‘compulsion’ in describing your artmaking.

Elijah and Michael open for business at the Totally Honest Bazaar during the Schemers, Scammers, and Subverters Symposium

Michael:

In some of the work that I’ve done with Elijah for Well Made Toy’s㏇, and in other Imagination Academy projects, there’s this imaginary or imaginative premise that then gets actualized in a playful way. Where the rules can change and there’s feeling highs and lows, there’s discomfort with engaging strangers outside the game who’re being invited to play. However in Well Made Toy’s㏇ there’s the fun and exciting pay off to playing the game, actually selling a toy that was made for the game.

The socio economic dynamics that surround the exchange of goods for money are complicated, emotional, and hardcoded into our culture. These things are challenging to understand and navigate for adults, but through gamification of capitol exchange young people can participate and learn from a safe and constructive method of engagement.

PLAYING WITH MONEY

Joseph at the 2017 KSMoCA International Art Fair shows off an artwork to a patron that later resulted in a sale

Katie:

Some recent research has found that kids behave more selfishly after playing with money, real or fake. (See the story in Pacific Standard magazine here: https://psmag.com/social-justice/handling-money-decreases-helpful-behavior-among-young-children ) The act of handling or playing with money results in a decrease in generosity and prosocial behavior.

What happens when we introduce the notion of selling artwork that children make – does the introduction of monetary exchange alter the creative experience for children? Does money change the act of creating for adult artists as well?

It’s curious to think that the materials we provide for children in play can actually prompt very different kinds of behaviors, emotional experiences, and levels of human connection or disconnect. Our choices in the environments we design for children may have greater implications than we anticipated.

Artwork by DeAndre at the KSMoCa International Art Fair

Michael:

In the first KSMoCa International Art Fair, Michael, one of the youth participants, was paired with well known and renowned artist Christopher Johansen. Together they made a few drawings using a pastel color palette. They were listed at $200 a piece and began to sell quite quickly. Other KSMoCA participants saw this capital enterprise and became enthralled by this commercial exchange. They quickly started making drawings and listing them at 10, 20, 50, 200, and 500 dollars. One of the minimally vocal youth scrawled his pricing structure onto an amazing drawing of transformer characters, “20 or 15$ if transformer fan, 5$ I mean it!”

Elijah makes a sale of a Well Made Toy’s㏇ toy

When Elijah and I began setting up for this project I let Elijah know he could set the prices for the objects we were selling. All the toys were made by him and his peers, they were quite simple but elegant and had wonderful pops of color accentuating their preexisting features. I had spent quite a few hours making custom mounts for each toy from some beautiful reclaimed wood. Elijah said “let’s sell them for $7 each!” I was shocked as selling them at that price wouldn’t even cover the cost of materials much less labor. However the goal of the project was not an in depth understanding of economics, so I agreed. Later after making a few hard earned sales, a more confident youth from the Living School came over to Elijah and offered him a photo copied single page zine for $10. It Seemed Elijah contemplated this for less than second and agreed to pay the price. I was shocked again, the premise of material and labor value was totally subverted, the desire for exchange was greater than any other criteria. As the money was his, I pulled $10 out of my pocket and handed it over, and continued to look on with amazement as Elijah handed the money over much more easily than anyone had for him.

TOY GUNS AND COMBAT PLAY

“Toys” in Michael’s collection of objects poised for future projects

Katie:

Children learn positive social skills through play fighting. In combat play, children learn negotiation, empathy, how to read complex facial expressions, and assess boundaries. This can be playing with swords, sticks, toy guns, and rough and tumble play. Dr Stuart Brown’s research has shown that this kind of play reduces violence in adulthood. It’s important for children to have access to all kinds of unstructured play time, including playing at fighting.

SOCIALLY CHALLENGING PLAY

O’Donnell proposes that working with children in the cultural industries in a manner that maintains a large space for their participation can be understood as a pilot for a vision of a very different role for young people in the world – one that the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child considers a ‘new social contract.’

Michael:

In any artmaking, but especially in socially engaged projects, there is the potential to push boundaries that begin to protrude awkwardly and ambiguously into the cultural contexts in which they occur. I often wonder what can we do playfully as adults that challenge societal structures, social norms, the status quo? Again, with any artwork, through viewing or participating one is being asked to understand a complex idea or set of ideas architected by the artist/maker. This form of expression is often attempting to create a dialogue between the work and those experiencing it. This is much like an invitation to play.

When this paradigm within art is extended into a social space, a simple subversion of an ordinary thing may cause participants to extend their comfort zone beyond the ranges in which they are currently held.

____________________________________________________________________

Links:

Preschoolers and gun play

http://teachertomsblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/gun-play.html

Old fashioned play builds skills

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=19212514?storyId=19212514

Penny Holland research on gun play

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2003/jul/12/schools.uk

What is notMoMA?

Text by Sara Krajewski

WStephanie Syjuco’s notMoMA (2010) is a work of conceptual art and social engagement, and the first work of social practice art to enter the Portland Art Museum’s collection. As a gesture of institutional critique, notMoMA questions the value and authority given to museum collections, who establishes and upholds that value, and how access to collections is granted. The Museum acquired the work in 2016 as a donation from the Portland State University’s Art & Social Practice program. It is unlike anything the Museum has collected, so far.

To exhibit notMoMA, Syjuco asks the presenting institution to identify and engage a group of artists. The makeup of the group is completely open and in its three iterations to date it has focused on students from middle school to college. The presenter also designates a curator (again, who takes that role is open for interpretation) and the curator’s job is to select works from the Museum of Modern Art’s online collection. The group of artists are then tasked with recreating the selected works, using only the digital reproduction available on MoMA’s website as their source material. The intention is to refabricate the works to near actual size, employing readily accessible and affordable art supplies or scavenged things. When finished, the re-fabrications are displayed in a gallery deemed “notMoMA” and presented with interpretative labels identifying the original art works and original artists, alongside the names of the re-fabricators.

The work came to the attention of folks at PSU’s Art & Social Practice program when it was produced at Washington State University, Pullman. notMoMA was soon wrapped into an upcoming event “See You Again” that a group of PSU students were creating for the Portland Art Museum’s Shine A Light series of socially engaged programs. The “See You Again” collaborators Roz Crews, Amanda Leigh Evans, Erin Charpentier, Emily Fitzgerald, Zachary Gough, Harrell Fletcher, Derek Hamm, Renee Sills, and Arianna Warner decided to take their programming honorarium of $2000 and use it to purchase a work of social practice art that they would donate to the Museum. They selected pieces by Ariana Jacob, Paul Ramirez Jonas, Ben Kinmont, Carmen Papalia, Pedro Reyes, and notMoMA by Syjuco. On Sunday, May 31st, 2015, a large group of guests attended a cocktail hour and heard impassioned advocates make political style speeches to sway the audience toward selecting one work. A caucus style vote commenced until, at evening’s end, notMoMA emerged the winner.

OK, notMoMA was selected. Then what? Stephanie Parrish, Associate Director of Programs at PAM and coordinator of the Shine A Light series, advised the PSU students to sit tight: to guide the work through the acquisition process, it was going to need a strong advocate in the curatorial department. That was me. In September 2015, I came on board at PAM, with a goal to reinvigorate the contemporary art program and I set about establishing a vision to welcome a much broader array of artistic practices and expression. I have always embraced an artist-centered approach to creating exhibitions and have had the opportunity to provide artists with platforms for experimental works. But to this point, I had not yet been in a position to bring a performative, socially-engaged work into an institutional collection.

The Museum, like all public, non-profit collecting institutions in the U.S., has a collection committee appointed by the Board of Trustees. This committee’s role is to provide oversight and approval of all purchases and donations that enter the Museum’s collection. Each PAM curator presents works of art to this group in meetings that take place every other month. I knew that notMoMA would be a challenge because we don’t have a history of collecting this type of work and it would be an educational moment for our committee members. I decided to do some advance prep with the committee co-chairmen to discuss the work and use that discussion to be prepare for questions that undoubtedly would arise: What exactly are we collecting? Will this create concern for MoMA that we are supporting this work? Questions came up about appropriation, copyright infringement, and how to ascertain the long-term value and relevancy of the work when it is not a fixed object or experience. We discussed the professional standards for collecting conceptual art and performance through certificates of authenticity; I gave a primer in social practice art forms and outlined our ongoing relationship with PSU’s Art & Social Practice program. A rigorous debate ensued. Even with lingering concerns, the committee voted to accept the piece.

With the official stamp of approval, the accessioning process began. In conversation with the PSU students, they expressed a desire to have a material form for the work that they could deliver. We settled on a set of instructions with attendant appendices that illustrate past iterations of the work. The instructions serve as our certificate of authenticity. An institutional concern came up around the artwork’s transfer of ownership. When a work of art enters the Museum collection, the Museum retains rights to it as a special class of property. We did not have any precedents for a process-oriented, idea-driven piece that takes changeable physical forms. Does the Museum solely own the idea and the right to recreate the idea? What are the artist’s rights to the non-objective, to the piece as intellectual property? If an organization wanted to present the work with the artist, would they have to acknowledge “collection of the Portland Art Museum”? Is this work “unique,” e.g. are their editions or multiples that the artist might show or sell in the future?

notMoMA has given me reason to reflect more deeply on the categories and designations that museum collections place on works that exist in the social sphere. Specific to notMoMA, the piece concerns access to art; by virtue of the institution’s internal control systems a layer of restriction has now been added to mounting the work outside of the Museum. It raises a relevant question: is this work really collectible? What does it mean for students of social practice art to create a situation where a socially-engaged work goes out of circulation, frozen in an institutional vault? Wouldn’t the work and its ideas be equally, or even better, served by multiple well-documented presentations that would be more readily available to larger audiences? The “See You Again” requests certainly asked the institution to stretch its definitions and its categories, and that is indisputably good and necessary. But did the act of collecting notMoMA stop it from reaching a heightened potential in the real world where real questions get addressed?

After all, Syjuco intends that notMoMA bridge a gap in students’ understandings of “high art” and invites them to come to a greater comprehension via their own do-it-yourself collective vision. Whether considered copies, translations, or even mis-translations, all resulting works are unique expressions in their own right. They exist outside the institutional framework, even in healthy opposition to it. As an exhibition illicitly “borrowed” from MOMA’s collection, notMoMA creates a dialogue between a localized audience and a powerful cultural institution that may be inaccessible to the participants and public alike due to geographical, economic and socio-cultural barriers. Syjuco also reflects on the aura of original works of art, challenges the consolidation of cultural wealth in major institutions, and reasserts the physical experience of art in the digital age. Now that it is in another institutions collection, does this affiliation further complicate the work? Or could it be seen to neutralize its criticism some?

After acquiring the piece, I felt an urgency to activate the work and justify its “value”. We presented notMoMA in the context of our year-long We.Construct.Marvels.Between.Monuments. series led by guest artistic director Libby Werbel. Werbel responded enthusiastically to including the work in chapter 3, MARVELS. She invited curators Shir Ly Grisanti (c3:initiative), Mercedes Orozco (UNA Gallery) and Melanie Flood (Melanie Flood Projects) to select MoMA works and area high school students from Jefferson High School, Gresham High School, and Reynolds High School to be the artists/re-fabricators. We also engaged a side project with c3:initiative, creating a space for documenting the process and giving more recognition to the student artists. We even got a best of 2018 mention in Artforum, courtesy of artist John Riepenhoff, probably the first critical attention the Museum has had in the print edition of the journal.

I am pleased and proud that the Museum has engaged with an important work of art, and of course I am pleased and proud that we can count it in our collection. Stephanie Syjuco continues to challenge me with the depth and complexity of her artistic inquiry. I’m grateful to the PSU Art & Social Practice program for making this engagement possible and allowing for this reflection of a wonderfully complex work. The number of questions notMoMA and the event/intention of See You Again continue to have for me attests to the importance of the work and adds dimension to the continuing relationship between the Museum and the PSU program.

About the author:

Sara Krajewski is the Robert and Mercedes Eichholz Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Portland Art Museum, Oregon. Over her three-year tenure at the Portland Art Museum, Krajewski has reinvigorated the contemporary art program through exhibitions, commissions, collection development, and publications, and she has fostered collaborations that bring together artists, curators, educators, and the public to ask questions around access, equity, and new institutional models. Recent and upcoming exhibition projects include: Hank Willis Thomas: All Things Being Equal; We.Construct.Marvels.Between.Monuments.; Josh Kline: Freedom; and Placing the Golden Spike: Landscapes of the Anthropocene. Krajewski holds degrees in Art History from the University of Wisconsin (BA) and Williams College (MA) and has been a contemporary art curator for twenty years, holding prior positions at the Harvard Art Museum, the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, the Henry Art Gallery, and INOVA/Institute of Visual Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. A specialist in transdisciplinary artistic practices, Krajewski was awarded a curatorial research fellowship from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and is a 2019 fellow at the Center for Curatorial Leadership.

Ethnography, Socially Engaged Art and a Preponderance of Dogs

Text by Allison Rowe

A researcher’s attempt to get a new perspective

Dog is one of the most used words in field notes I recorded during the two months I spent studying a collaborative, socially engaged art project in the winter of 2018. The project that the artists worked on was not about dogs but rather about technology, somatics, and fostering embodied connections between people. It was a beautiful, complex work that helped me learn new and unexpected things about museum-supported socially engaged art, community, and generosity. The dogs who pepper my notes largely just walked by me through the space where the artwork was taking place. As an artist turned art education “ethnographer”, I diligently took note of these dogs, what they wore, how they moved, and the people who walked them. Though my mentions of dogs are brief and lack the depth of my writings about the collaborative processes of the artists and the institution I was trying to learn about, the dogs are still interwoven throughout my notes, like pinecones amongst the dense dark green branches of a fir tree. While I did not realize it then, my accidental fixation on dogs illustrates just how much one’s own life can color individual perceptions of socially engaged art, even if, like me, you are attempting to look at things in a new way.

At the time of my canine preoccupation, I was a doctoral student studying gallery and museum supported socially engaged art. I began my research project because a decade of making, talking, and reading about socially engaged art had attuned me to a gap between my lived experiences within the field and ways that others (particularly academics and museums) seemed to describe projects. I observed that much writing on socially engaged art articulated or analyzed the final outcomes of a project, never getting to what most interested me as an artist—the slow, sometimes uncomfortable, mundane ways that a collaborative, institutionally-supported work unfolds. Bishop (2012) identified how the logistics of art critical and academic research don’t always align with the structure of socially engaged art which she explained is, “an art dependent on first-hand experience, preferably over a long duration (days, months or even years). Few observers are in a position to take such an overview of long-term participatory projects” (p. 6). As a socially engaged artist I agreed with Bishop and decided to structure my research so that I could gain a long-term and social perspective of the ways artists and museums work together.

In late 2017 I developed an ethnographic case study research design with the guidance of my dissertation advisors. Unlike art critical methodologies, ethnography prioritizes the in-situ grasp of a culture or community over time, largely through observational and discursive methods. As Marcus and Myers (1995) assert, unlike most artistic discourse, ethnography is not concerned with defining or critiquing what art is, because it is focused on “understanding how these practices are put to work in producing culture” (p. 10). I postulated that ethnography would allow me to follow the full lifecycle of socially engaged art projects from preliminary discussions, through to post-project debriefing, thereby offering the potential for new insights into gallery and artist collaborative processes. I was drawn to the ethnographic emphasis on remaining open as possible during research so that unexpected themes, unspoken participant beliefs, and/or non-obvious factors influencing a particular social situation might become visible. For example, at my first research site I realized that the backdoor to the gallery (which led into the staff offices) was commonly used by the public because the organization was open to their community stopping in any time to make use of the institution’s resources—something I may not have realized unless I jotted down how everyone entered the space. Part of what I hoped this type of ethnographic observation might offer me was a more objective perspective on socially engaged art. Like many people who work in participatory art, I get deeply invested in my projects and the people I work with, making it hard for me to separate my emotional, critical, and personal perspectives when describing my artworks to others. I theorized that taking on the role of an ethnographer might create some productive distance between me and the socially engaged art projects I was learning about so that I could get a fresh perspective on institutional and artist collaborations.

My ethnographic research design required me to temporarily relocate to the cities where the projects I was studying took place. When I arrived at my second site in January 2018, I brought with me my nine-month old rescue dog Sprout who my partner and I had acquired three months prior. Though adorable, Sprout was a high energy puppy who had learned a multitude of bad dog behaviors in the few months she lived in an overcrowded Ohio animal shelter.

Each day, before I arrived at the museum to work with the artists on their project, I took Sprout out for at least a one hour walk, during which I tried to teach her how to not pull on a leash, chase squirrels, bark at people, or eat garbage. I could then leave her for a maximum of five hours before I needed to return home and take her out for another hour or hour and a half, often in the pouring winter rains of the Pacific Northwest. Sprout frolicked around me licking my feet and trying to jump onto forbidden surfaces as I typed up my field notes each day. She sat beside me on the couch as I used one hand to edit images for the project, the other to pet her head. Sprout ripped up toys and fancy treats in the bathroom while I conducted Skype interviews. Occasionally, she would sleep beside me while I read over my notes. Other than my research, the only thing I accomplished in that two-month period was to teach Sprout how to play fetch in order to more effectively tire her out. To say dogs were on my mind during my research is an understatement; my puppy training brain was liking a weather vane, oscillating towards any canine who crossed my path, likely with the subconscious hope that I might discover how to better control my dog.

For all intents and purposes, Sprout, like the dogs in my field notes, has nothing to do with my research. She will not be mentioned in my dissertation, nor are any other canines discussed analytically in my work. And yet, their presence in my notes offers perhaps the best window into the limitations of both ethnography as a method for studying socially engaged art and of socially engaged art storytelling. Ethnographic case study, like socially engaged art, is something which unfolds over time via the mutual participation of people in a specific context. Both are fields made up of lots of participants who come to a project for different reasons, with different intentions, aims, and feelings. Any or all of someone’s life situation may be expressed or not, in action or words, at any point during a project. The challenge to articulate a socially engaged art work, be it by artists, the institutions who support them, or a researcher, will always reflect the plentitude of perspectives that the author inhabits.

Though I entered this project with the belief that ethnographic case study might provide me a more judicial viewpoint of socially engaged art, instead it reminded me of the impossibility of crafting a singular ‘accurate’ story of any socially engaged art project by highlighting how my dog/life balance was shaping my research. While ethnography offered me an innovative toolkit for approaching socially engaged art, it was not a magical periscope that stopped my life or feelings from shaping my encounter with the project. Rather than viewing the impacts that social, emotional, political, and personal experiences have on socially engaged art as a potential limitation to how we tell the stories of projects, I believe artists, galleries, and researchers simply need to be more transparent about these factors, both during the execution of a work and in its dissemination. This honesty and vulnerability, whether it is about a poorly conceived timeline, a longstanding friendship between a curator and artist, or a fixation on dogs, will help foster more inclusive dialogues about socially engaged art and will support our field in continuing to grow in new and exciting directions.

References

Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial hells: Participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. London: Verso Books.

Delamont, S. (2008). For lust of knowing: Observation in educational ethnography. In G. Walford (Ed.), How to do Educational Ethnography (Ethnography and Education) (pp. 39–56). London: Tufnell Press.

Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Marcus, G. E., & Myers, F. (1995). The traffic in culture: Refiguring art and anthropology. (G. E. Marcus & F. Myers, Eds.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Our Daughter, the Artist

Text by Hue Boey Kuek with input from Say Cheong Ng

To get the long view of an artists career and work, we asked the parents of Xi Jie Ng to offer us some insights. Xi Jie offers an introduction, and questions were prepared by Spencer Byrne-Seres.

I once shouted at my father through sobs on our porch, “Trying to live your dreams is the most practical thing you can

do in life!” and told him to read his Dalai Lama book on happiness. Two years before that, my father demanded to know my “plan b and c” when I quit my arts administration job to be an artist. Today, external institu- tional validation and experiencing my and my peers’ work have helped my parents bet- ter understand their eccentric firstborn and what it means to have a creative practice. I think they choose to see a certain side of my work in a somewhat do-gooding light; that is grand progress for us. Say Cheong is known to be an enthusiastic, task-oriented eager-beaver; he once went up to my high school theatre studies teacher and told him, “I’m worried about her. She’s coming up with weird names for herself.” Hue Boey is a hardworking, empathetic worrier-type; she encouraged my childhood love for crafts, drama and reading. Both grew up poor in developing Singapore, are now financial- ly worry-free and have never changed their civil service jobs. Putting myself in their shoes with a lot of grace (as is often need- ed in familial interactions), I see how it is terrifying that my work may challenge state control and that my life might manifest in patchwork ways wildly different from the safe, hammered-into-the-cultural-psyche Singaporean standard. But which child doesn’t yearn for profound understanding, acceptance and support (in that order) from their parents? I think a lot about karma and why we are born to our parents. Recently, my mother told me I am resourceful and suited to this crumbling world, that as a result of me, she and my father experience things they usually do not. This can mean putting on a new lens – as she wrote, to my infinite delight, “Many of the things we do, even in everyday live, is art, for example, cooking a dish, arranging furniture or deco- rating our house, gardening, sewing, writing, etc.” I am deeply grateful for their sup- port through confusion, and that my artistic practice is now, for us together, a portal into my cosmos and many more worlds that may rightly excite, shock and abhor them as they age.

-Xi Jie Ng

When did you know your daughter was going to be an artist? What were the signs? How did you feel, knowing this was her chosen path?

Xi Jie had shown a lot of creativity since young. She also enjoyed activities like drawing, art & craft and speech and drama classes. Birthday presents for some family members were always very interesting creations of hers. When she started pursuing theatre studies in junior college, that was the start of more serious pursuit of her interest in creative work. She surprised us by her projects which were out of the ordinary. After graduation, she took on a job in the National Arts Council where she organised the first silver arts festivals (for seniors) in Singapore. Her ideas of getting seniors to appreciate and participate in creative activities were very novel. She also embarked on projects like filming which showed her other talents. She went on to do other projects. We saw that there was no limit to what she is capable of and there was no doubt she would continue to pursue her interest in the arts.

We were at first a bit concerned that she was not taking the conventional path like other kids. We felt that it was a waste of her talents – she was good in both the arts and sciences subjects, including mathematics. She is intelligent and we were sure she could excel in the more conventional route. Like many parents who would like their children to have a secured future, we were concerned if she could make a living being an artist. Despite our reservations, we continue to support her.

How are artists viewed in Singapore in general?

Our sense is that there is greater understanding and appreciation of artists and their work in Singapore especially by the younger population and post-baby boomers given they are mostly educated and also more exposed to art through today’s very borderless world and greater appreciation of things beyond the science of things and materialistic pursuits.

How would you describe Xi Jie’s work? What type of artist is she? How is her work different or unique from other artists?

As amateurs in the field of art, we think that Xi Jie’s works is very varied. This reflects her multi-talents and versatility. Her work covers drawing, illustrations, writing, producing films, acting, photography, installations, etc.

What stands out about some of Xi Jie’s work is that they seem to originate from her interest in people and things of the past. For instance, capturing the daily lives of her grandmothers in film, telling the story behind Singapore’s pioneer busker in film, an exhibition on bunions which is a body defect affecting many people, getting seniors to go beyond their limits to come up with creative art and craft, working with prisoners on art projects, etc.

Some of her work is abstract and we could not immediately grasp the message behind them. Examples include her work at a few residency programmes. One of these is a picture of her against the moon that she took at a residency in Finland. Another is a project she did in Elsewhere (North Carolina) where she created a space like a Japanese capsule hotel.

How does watching Xi Jie’s work make you feel?

Xi Jie’s works have opened our eyes and at times make us feel that she lives in a different world from what we are used to. Our background is in engineering and science and our thinking is very black-and-white. We have been prepared to enter her world and experience it. Our visit to Portland in 2017 had given us the opportunity to experience her projects which we were amazed with.

What have you learned from Xi Jie’s work? Has Xi Jie’s work challenged you, or changed your views on anything?

Needless to say, it has challenged us to be very open to artistic work and to appreciate that the work has meaning to the artist behind it that we should never discount or even laugh at. The more abstract the work is, the more we have to challenge ourselves.

We learnt from Xi Jie’s work about limitless imagination, of making connections with things, people and between them and seeing meaning beyond what our eyes and our mind typically tell us. We also learnt that there is innate potential of artistic work in everyone. Many of the things we do, even in everyday live, is art, for example, cooking a dish, arranging furniture or decorating our house, gardening, sewing, writing, etc.

What is your favorite project that Xi Jie has created? Describe the project and how you engaged with it – were you a participant, saw it at an event, saw documentation (photos and videos taken of the project) ?

Our favourite project is the short film about the daily lives of her grandmothers. We are delighted that she takes an interest in how her grandmothers are spending their silver years and wants to document it in a film. The film also gives audience a glimpse into the lives of the ordinary grandmother in Singapore.

We were not involved in the filming but got updates from her. The grandmothers were as expected, accommodating. We are sure that Xi Jie learnt something more about her grandmothers through the project, for example, her maternal grandmother attended dancing class.

What is one project or artwork you wish Xi Jie would do, that she hasn’t done?

Her father hopes that she can do a project to get the community’s support for creative art for seniors. The Silver Art Festival was a good start and it is now an annual event. WIth an aging population, there are opportunities to engage more seniors in art activities that they can enjoy.

Tethers

Text by Elissa Favero

On the second day of the year, I learn that my sister has been diagnosed with thyroid cancer. She’s over 1,700 miles away, in Chicago. She announces the news to our family over text. And though she and I will speak on the phone occasionally in the next months, most of the updates ahead will come via Short Message Service (SMS). Some reflect her lawyerly training—informative, succinct, definitive in the face of uncertainty. Others—many others—are silly. As she plans for the isolation her radiation treatment requires, she writes of her Laura Ingalls Wilder preparations, of the supplies she had gathered for her time of hunkering down, her “nuclear winter,” as she’s calling it. Her partner, fortunately, is able to stay in their condo but has to relocate his bed to the couch. She can’t be within three feet of him or anyone else for eleven days. She’s played The Police’s “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” for him the day before she begins treatment, she tells us. On the fifth day of the isolation, she writes, “At least the treatment seems to be working.” In the picture she attaches, her face glows green from the reflected light of the computer monitor beneath her face. In response to these messages, my Mom writes from Maryland with dogged optimism and over-the-top, animated emojis. She’s 600 miles from my older sister, some 2,300 miles from me in Seattle. My younger sister, in Baltimore, is quick, wry, just as she is in person. My Dad is earnest, self-deprecating, obviously deeply concerned. “That is good news,” he replies to my older sister after an early report with some bit of encouraging information, some mitigating detail. “You are in my heart as I travel,” he tells her, and us, on his way to visit my grandmother in Montana.

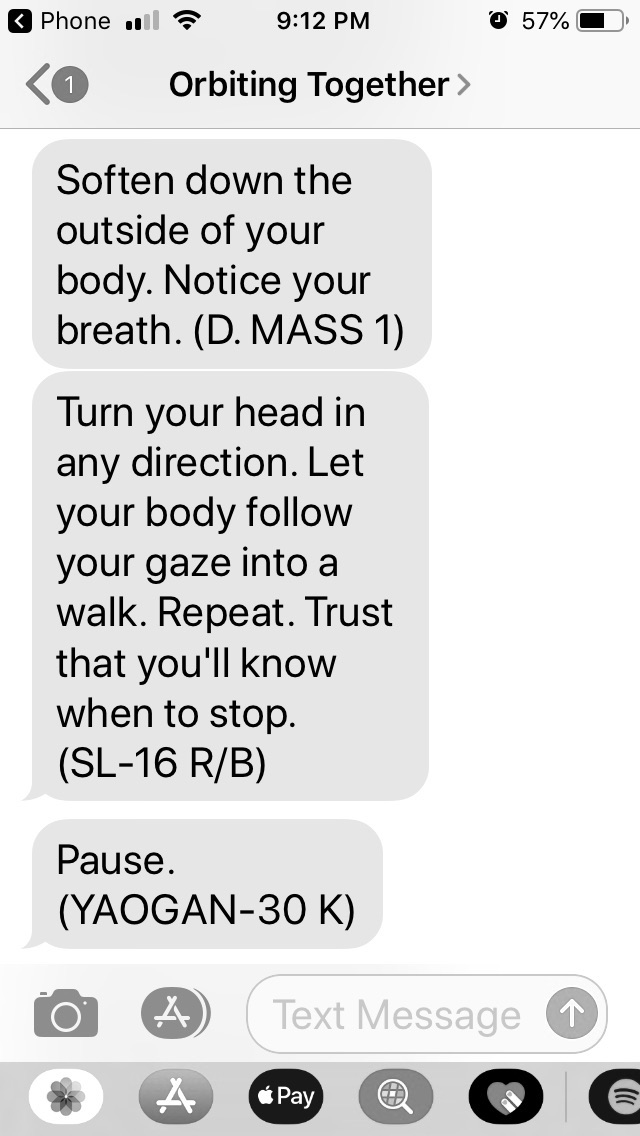

Later that month, I subscribe to a series of SMS notifications. These come daily, sometimes twice a day. Each is an invitation to participate, from afar, in a winter program at the Seattle Art Museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park. Orbiting Together begins with a low-stakes prompt on January 26: “Recall which pair of socks you chose to wear today. Observe how they feel on your feet. How long have you had them? (NAVASTAR 71: USA 256)” I try hard to remember before lifting my pants leg to reveal rose-patterned knee-highs. They were a Christmas present from my older sister the year before. I think of how many others are receiving the message, trying to recall their wardrobe choices of a few hours before, wiggling their toes, stealing glances down at their feet.

—————————————–

Tia Kramer, Eric J. Olson, and Tamin Totzke composed the daily notifications for Orbiting Together in response to the paths of satellites traveling above the sculpture park. Some three thousand pass over the park each day. These satellites, part of the United States Air Force’s Global Positioning System (GPS) that launched in the early 1970’s to track and transmit data about time and location, make it possible now for us to pull out smartphones, swipe and tap, and find exactly where we are. They make of geography something exact and objective. The cell phone messages the artists use, meanwhile, are conveyed to us by way of towers communicating at different radio frequencies. Like the satellites, the towers transmit at a distance. Even nearby, these satellites and towers often go unnoticed, the visible/invisible infrastructures that allow for our digital lives to play out via screens sensitive to touch.

The messages ask me to pause and engage. The artists meant to co-opt the contemporary technology of digital capitalism and subvert it. They want to draw us back into the reality of what’s passing overhead or nearby, to our own bodies and feelings. The information they convey is the action of a passing satellite. The rest is suggestion—the prescribed action up to me.

More often than not, I admit, I imagined instead of enacted. My favorite prompts—the ones I was especially likely to follow—ask not for physical engagement but for more basic awareness and perception. “Listen for a rhythm in your environment. Consider your heartbeat.” came the prompt late afternoon on January 31. I listen to the hum and horns of I-5 traffic outside my window. I can’t hear my heart, so I put my hand to my chest and find its rhythm. Where, I wonder, does touch become sound? This particular message corresponds to the BEESAT-2, the Berlin Experimental Satellite that allows for amateur radio communication.

Ten days later, I hear my phone buzz and reach out for it, reading “Look to the satellite flying overhead. Cup your hands around your mouth and whisper a message to someone who is very far away.” The corresponding IRIDIUM satellite, I learn later from the artists, provides satellite phone coverage for people in remote locations.

I think of the main character in the 2001 Hong Kong film In the Mood for Love. At the end of the movie, Chow Mo-wan comes from Hong Kong to the ruins of Angkor Wat. He has earlier told his friend about an ancient practice of making a hollow in a tree, whispering a secret inside, and covering the opening with mud. In Cambodia, Mr. Chow touches his hand to a space in the temple wall before bringing his mouth to it. After he leaves, we see that he has stuffed straw into the void, pushing back his words as far as he can reach. The words themselves we never hear. As he stands, leans, and whispers, the film’s music swells and the camera circles, a satellite around him.

—————————————–

In-person, participatory performances bookend Orbiting Together’s month of daily texts. At the first, I feel my introversion as I arrive and survey the scene from the edge of the room. I’m relieved when we’re called together, coordinated into movement. Weeks later, at the start of the second performance, a woman asks for my arm as she adjusts her shoe. At once I feel helpful, more at ease. About halfway through the performance, a prompt directs us to “Sink into the floor and allow yourself to be held by those around you. Notice how you are holding up others. (SL-14 R/B)” I laugh with the three people I happen to have been near and fallen with. We are preposterously, precariously arranged, backs on the ground with limbs extended, overlapping, supporting or being supported. I’m being stretched past the polite disregard I cultivate on the bus and in other public spaces.

At this second performance, there are professional dancers among us. They perform with us and then coalesce to extend the directives with the grace of bodies professionalized for movement, becoming fonts of trust and mutuality in a sea of strangers who’ve been asked over the course of these weeks leading up and now this evening to come closer and closer. “Feel the presence of others. (WISE),” we are directed. “Fall with someone. (D. MASS 2)…Notice your hesitation. Notice your surrender. (ALOS: DAICHI)” And later, “Orbit around somebody you don’t know. (SAUDISAT 1C: SO-50)…Observe your heartbeat. (FENGYUN 3C).”

—————————————–

All told, 422 people subscribed to Orbiting Together’s notifications during January and February. Many also posted to an Instagram account, documenting their responses to the daily prompts through photographs and short videos. I’m struck as I scroll through these that the participants aren’t touting the beauty or good taste we’re often meant to see in selfies or vacation photos. Instead of assertions of individual identity, the responses feel more like a chorus of gentle echoes. So this is what it looks like when you spin in place, noticing your dizziness, imagining satellites travelling faster as they get closer to earth.

The artists behind Orbiting Together conceived of their project as a rhizome—in botany, a system of roots that extends laterally, without a clear center. “This project,” they write, “uses a network of satellites flying over the Seattle Art Museum Olympic Sculpture Park as triggers for messages encouraging participants to engage their somatic awareness. Individuals opted into the system create a rhizomatic positioning system composed of people in the place of technology.” The Olympic Sculpture Park is the nexus of activity, with satellites passing overhead, triggering the messages. But the recipients and enactors themselves define the network, its reach and shape morphing and mutating over the weeks. In their book A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari similarly use the metaphor of the rhizome to put different disciplines in conversation and send out reverberating lines of communication. “All we talk about,” they write in their introduction to the book, “are multiplicities, lines, strata and segmentarities, lines of flight and intensities, machinic assemblages and their various types…It has to do with surveying, mapping even realms that are yet to come.”

We orient ourselves relative to people, to a constellation of relationships both casual and serious, immediate and distant. These comprise single exchanges, rapports formed by routine, brief periods of intense intimacy, and bonds that will last a lifetime. These relationships help tell us, in big ways and small, who we are and how we belong together.

This last year and a half, I’ve experienced the remote sickness and recovery of first my father-in-law and then my sister. In the last month, I learned from a friend across the country about the sudden, devastating death of her husband. Perhaps the reverse side of Deleuze and Guattari’s underground, extending roots—always expanding and coalescing, spontaneously forming—are the ways history and shared experience have tethered us to each other. “Tether” comes from Old Norse, meaning “a rope for fastening an animal” and, by two centuries later, the “measure of one’s limitations.” We are, in a sense, beasts of burden to one other, figures of responsibility and obligation. But instead of selves bounded and begrudgingly beholden to each other, I think of Deleuze and Guattari’s multiplicities and intensities moved above ground, those communications via satellite and text, those tracks and tethers that allow me to feel the pull of my sister, my father-in-law, my friend, the tug I perceive at my end, the connection that reaches between them and me and measures the length of the distance and also forms its link.

The rhizome: a ribbon of highway ceaselessly carrying drivers and passengers near and then past my window; an arm extended to a stranger when she needs it; and a happenstance, precarious pile of laughing bodies on the floor of a museum. And the tether: the teasing and self-deprecation and, at the best of times, vulnerability and fierce love that took years to bloom between us, that I want to tend across miles and years.

My sister and I will likely never live in the same place again. There are good reasons for that—differences in professions, interests, temperaments, values. Sometimes these can feel like vast chasms. It can be hard to say the right words to each other. I know I’ve said the wrong ones, said what felt like betrayal, heard what sounded like indictment. Or said nothing at all. I feel the tug, though, of her typed texts or animated gifs on my end and I tug back. We orbit together in a perpetual dance of distance and immediacy, uncertainty and intimacy.

Connections, though, can be cultivated, can extend into territory as yet unmapped. Toes and heartbeats and whispers to ourselves, observations from a window or a proffered arm or bodies right close to each other, calls and texts with those we love already: these are the realms of self-awareness and friendship—however temporary or lasting, however unexpected or made of what we think we already know so well—that pulse with the present, that are, in Deleuze and Guattari’s words, the realms ever yet to come.

I look up. I reach for my phone.

The Cat Houses of Morgan Ritter

Text by Spencer Byrne-Seres

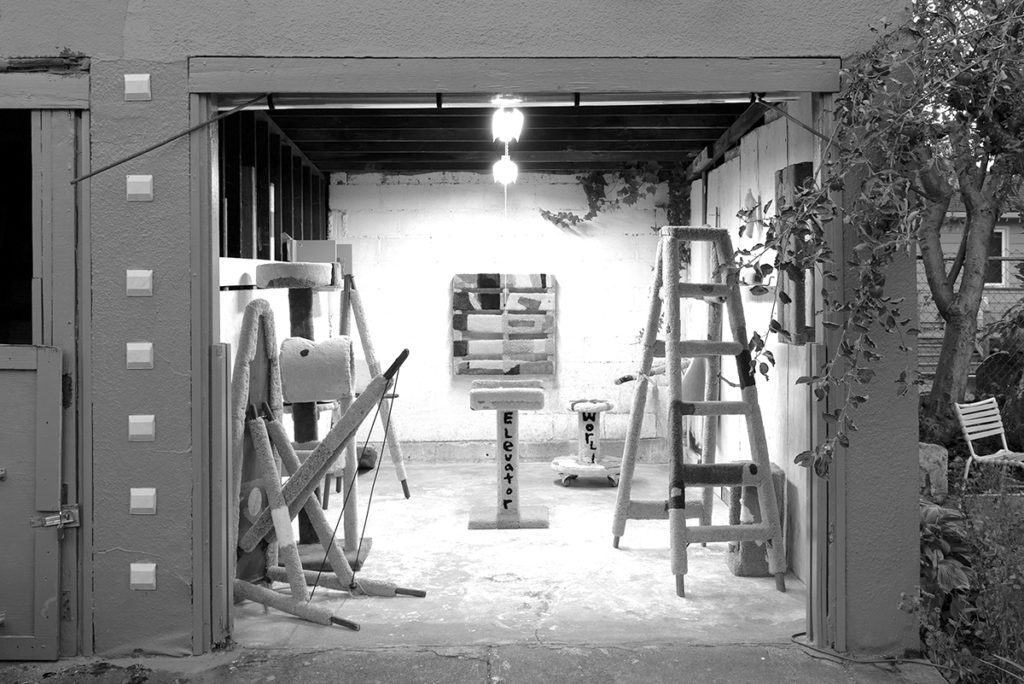

“Incidental” was one of the first words that leapt out at me in my conversations with Morgan Ritter about The Cat House Settlement. Incidental, a sort of by-product. An incident, a response, a result. Not necessarily an accident. Maybe an attitude, a mood, a situation. That the cat houses appear abstract, that they can be understood as art, is incidental. So clear are their primary function, that when Morgan was walking down the street carrying the ladder (see fig. 1), a couple ran out of their house to confirm and exclaim that it was, in fact, a cat house. These objects are everyday object, human structures, renovated for cats. Incidentally, they are covered in carpet.

I first came across The Cat House Settlement in a series of Instagram posts that Morgan made about their existence. The caption on one post read: “LOCAL OPPORTUNITY TO SQUEEZE MY CAT HOUSES: 3 of my “cat houses” (patchwork carpeted sculptures for cats aka human’s perception of cats via human language and material) are FOR SALE in PORTLAND…”

Human’s perception of cats via human language and material.

Morgan’s cat houses are questions, a material research project into perception by an artist who desires to move beyond simple human audiences. They began in response to the artist’s disappointment and trauma with human politics and the human art world. The cat houses offered a respite from a caustic environment though dissociation: a fantasy project, a post-human query into interspecies communication. It felt like the missing piece to SoFA Journal’s chosen theme, so I contacted Morgan immediately and we began talking about the work.

Morgan has been making these houses for years. All of the objects are found objects, as is most of the carpet. They are remnants that she finds on craigslist or in free piles to which she add innumerable hours of time and attention. There is a ladder, a pallet, an ironing board, a block of wood, a box, and a stick, all covered in carpet. Morgan states that “the scrapping is a technique of survival that I have cultivated in my creative practice. Working with what I have to achieve something paradoxical and almost unimaginable.” To this end she painstakingly collages together carpet, cut into shapes then assembled together in an instinctive way, through what is described as a snowballing process. Their composition starts with one shape or patch of carpet, then slowly envelopes the object. The colors are mostly muted tones of purple, blue, and beige; tones of carpet you would already find covering other cat houses. Interspersed in some are text: world, elevator. Poems for the humans, jokes for the cats, or vice versa.

When we talk about the cat houses, we always talk first in terms of cats. How do they climb them? Do they like them? What cat considerations are you making? Are they for particular cats, or a general cat audience? On a certain level the cat houses don’t need cats to function. Morgan is making assumptions about what cats might be interested in, but the process is dialogic, or even speculative. They are projections, imaginations by a human of what cats might need or want or be interested in. There does not need to be consensus among cats just as there does not need to be consensus among humans. And it is in the reception of this work where we learn about how others perceive the world. When I arrived at the studio, there was a cat, perched in the upper basket of the largest house, staring at me at eye level (fig 2). This almost came as a surprise. I wasn’t sure if the cats really engaged with the houses, but in that moment there was no doubt who the work was for.

Each of these objects points to an obvious fact of life: cats and humans cohabitate the world together. We share bathrooms and bedrooms and kitchens. And we fill these spaces with stuff. Stuff mostly designed for humans, save the dog bed in the corner or the kitty litter box in the garage. We expect cats to live in our houses, walk on our slippery floors, scramble over our appliances and underneath our beds. Morgan is pushing back, by wrapping our stuff in carpet. “No,” she is saying to the chair, “you are not just for humans.” The cat houses are puzzles, both for cats and for humans. For instance, there is a hunk of wood that is covered in carpet on one side, that rests on two sharpened pencils, titled “INTERSPECIES WORK TABLE” (fig. 3). The function of this object is no more apparent to the human than to the cat. But to both it poses a challenge, and perhaps an invitation to collaborate in what Morgan sees as a launchpad for post-human thinking.

The work has been presented in a number of ongoing formats: normally the cat houses live in Morgan’s garage studio, their natural environment. Cats and humans may come and go, seeking or discovering the cat houses as I did when I arrived for a studio visit. The work was also presented in a garage in Seattle. And online, the work is shown through Morgan’s website in a mock Craigslist page that lists all of the pieces and their prices. This last presentation is like insurance, lest the art world try to re-re-appropriate the work as sculpture. “This is not an exhibition,” she writes in reference to the works living in Seattle. The Craigslist page builds a certain logic of transaction into the work that is otherwise the product of “dissociation and fantasy.” The logic of transaction underlines the function of the work: she is creating supportive structures that are in turn able to support her.

As Morgan makes clear, the cat houses are not for the gallery; they have no function there. But where does art serve a function? Why does it have to live in ascetic white boxes and cold warehouses? We grapple with these questions much like a cat on a wooden floor, sliding around, trying to find our grip. Function is at the heart of Morgan’s inquiry, challenging the status quo, retreating from the standard functions and spaces in which art is produced and consumed. She has been making a list, attempting to catalogue the functions of art:

Art as a compromised result of accommodating an institution’s requirements

Art as no vacancy, or vacancy

Art as all you can eat