Category: Interviews

Peeling the back the layers

Text by Kiara Walls with Jodie Cavalier

“I feel my onion has another audience that has grown inside of it or something.”

-Jodie Cavalier

I lost my grandfather earlier this year and have since been navigating the complex layers of grief. After returning to work following my bereavement leave, I had a conversation with my coworker, Amy Bay, from Northwest Academy, where I serve as the Dean of Students. We discussed my desire to honor my grandfather’s memory by using his belongings to create something meaningful. Amy mentioned the work of Jodie Cavalier, who explores grief by incorporating her grandfather’s items into her pieces. Jodie’s exhibition, titled “Fool’s Gold,” was showcased at Holding Contemporary. I found Jodie’s work inspiring and was intrigued by her approach to grief. I wanted to have a conversation with her to gain a better understanding of her artistic practice and her relationship with grief. This conversation brought me comfort, as it allowed me to explore different ways of processing grief that aligned with my own experience within my family.

Kiara Walls: How are you?

Jodie Cavalier: I am doing okay. I have had a pretty rough year losing a lot of elders, so I feel I’m in the beginning and middle of multiple grieving processes. So it’s been a heavy start to this new year.

Kiara: Yeah. I can imagine. I resonate with that too. I’ve recently lost my grandfather over winter break, which has been my first close experience to grief. How have you been processing your grief? Because, you know, a lot of people refer to grief as a layer of an onion.

Jodie: I feel my onion has another audience that has grown inside of it. I think that when my grandfather died, it was very abrupt, even though he was older. He died from Covid, so the whole weight of the pandemic and all of those fears manifested in something. I think that people who have lost someone during the pandemic have maybe a different relationship to it because of that. I hadn’t really thought of that. Maybe that is part of the onion of grief, collective grief,around the pandemic. I do feel I started to process some of that when I was going through some of his stuff and then I was hit with both of my grandmothers dying in the last year, pretty close together. So it just kind of piled up in a way. I think I’m in the very beginning of it and trying to figure out what processing that is. I think that it’s so different for everyone and I don’t know what it is for me quite yet.

Kiara: I totally feel that. It also resonates with me what you were saying about how different people are experiencing grief at the same time, with Covid. That makes me think of the phrase “six degrees of separation,” but six degrees of grief and how we are connected in that way. I was actually introduced to your work through a coworker of mine over at Northwest Academy, Amy Bay. We were talking to each other about my grandfather’s passing. I was telling her about how I’m interested in collecting his items and somehow doing something with them. Then she told me about your work and your show at Holding Contemporary. I was really interested in your work and wanted to talk to you about your practice. I’m interested in hearing more about what helped you through this experience of grief and what your understanding looks like for you and how you process it.

Jodie: It was a natural kind of progression to make work about my grandfather in general. I actually made work about him before, when I was younger.

Kiara: What was that work of?

Jodie: That work was a lot about the body and when the body begins to fail. He had some health concerns and he had parts of his leg amputated because he had diabetes. I was really thinking about aging and the body and this kind of promise we think the body makes to us, and then breaks. We’re in this together and then our body starts to fall apart and you just feel betrayed by your own body. I think a lot of my work is really kind of based and seeped in the human condition. A big part of that for me and my lived experience is the relationships I make with other humans and even more specifically the relationships I have with my family. That has come through in the work for a long time in different ways. Some work is more overt than others. It came about pretty naturally to start to make work about or around him, ideas of grief, familial things, all of that kind of just came together. I was in conversation with Holding Gallery for years before we did the show, “Fool’s Gold,” together. I just didn’t feel what I was working on made sense in a gallery at that time. When they first approached me, I was doing a lot of community organizing projects and food projects. I don’t have a need for showing that for authoring the community work I was doing; the priority was different. When I started to make work that was more physical, fine art type objects, we revisited the conversation around having a show. I didn’t really think about it as processing of my grief. Now I think about everything as processing grief, in some way. But at that time I was just kind of going through the motions of remembering him in specific stories and his personality, and then going back to my grandparents’ house and taking random objects and remembering things from them. Then it kind of started to accumulate and just thinking about some of the things he believed in and hoped for, and all of those started to surface in a way where I was, I started having more fun with it. He would get a kick out of some of the things that I was making and messing around with, and whatnot. He was always a supporter of weird creative endeavors. He didn’t understand them, but was just supportive of them. I wish I could have shared with him some of the things I made. I think he would’ve got a kick out of it.

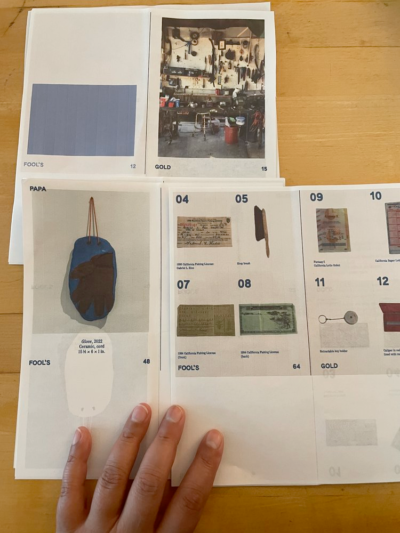

I made a lot of work and then kind of put it into a book form because I wanted to have them hold a different space. There’s a lot of writing that I had been doing for several years about my family, specifically my grandparents, but I wanted to have a place for those to exist alongside the objects. It was really fun. I got to work with Holding Contemporary and, and one of their designers, who is amazing. She basically just donates her time and service to working with Holding. She has a design job with a couple of other folks called Omnivore. Her name’s Karen Sue, we went back and forth with all of these kinds of ideas on how to put the book together so it didn’t just feel like another publication. We put a lot of thought and process behind everything.

Kiara: Yeah. This was beautiful (looking at the publication).

Jodie: Thank you.

Kiara: Was this at your exhibition opening?

Jodie: It was at the end. So we didn’t have a formal opening and instead we had a closing and book release towards the end of the exhibition. I was working on it alongside all the work, but in order to get the exhibition documentation photos, we waited until the exhibition was fully up and finished the design afterwards. My friend, Joanne Handwerg, wrote a really thoughtful introduction piece about absence and longing.

Kiara: I can see some of those details designed in the book. I’m wondering, on some of the pages we see the object and then on the page right next to it, there’s nothing there. Is that speaking to some of the themes around absence?

Jodie: Those two pages where there’s the image of the artwork and then next to it there’s a high contrast absence of the image. We talked a lot about ghosts and ghost images. Then also just the impression, something leaves too. There were a lot of really great conversations I was able to have where there were some aesthetic technical decisions, but they were all made from a conceptual and poetic place. It was fun to talk through what it means to have a certain kind of decision that impacts the reader and even things like paper choice and what that feels like. There’s also a clear film that also mimics that ghost quality.

Kiara: This is beautiful. It sounds like your process or approach with this body of work was an aesthetic approach, but also a theoretical approach, like bringing the ghost aspect into the work. I think the way that you present it is really amazing because from being the reader, I could sense some of what you were saying just now within this. Have you thought about where the work could live in the future? Once you’ve done this show, have you thought about presenting the work in other places? Or how do you feel about it being presented in other places?

Jodie: I’m definitely open to that.

Jodie: Yeah, they have lives, I think, where they exist in this one wave and then in book form. I was also pondering how objects could possess autonomy and be strong enough to exist outside of the exhibition. I’m not opposed to any of that. I have a practice, especially with object making, where I often Frankenstein old pieces together. I was brought up to be resourceful, so sometimes I take a piece apart and turn it into something else. I haven’t done that with any of these works, and I don’t know if I will, but I try not to be overly precious about some of the things. I think they have their own why, so why not.

Kiara: You said you don’t want to be overly…

Jodie: Precious, yeah.

Kiara: And you don’t.

Jodie:If I needed to use the base of this sculpture for something else and didn’t have the resources to make a new one, I would just have to make the decision to use it, you know? I also think that, for a lot of reasons, I haven’t had the luxury of having a place to store all these things. Maybe a storage unit or something, but I don’t want to end up with a huge collection of objects I’ve made just sitting there. It would be much better for people who enjoy and find meaning in them to have them. And many people do. That’s also why my work often fluctuates between objects and non-object forms, or even prints and works on paper that are easier to distribute or more accessible in that way. I guess I’ll have to think more about it, but right now, I can’t think of anything I would never give away, you know?

Kiara: Yeah, I get that. I believe social practice art could be an avenue where you don’t have to worry about those types of questions because there’s an ephemeral aspect to the practice. Can you talk a bit about how your work incorporates social practice art or share some projects you’ve done in the past that have incorporated social practice?

Jodie: Yeah, I never really thought of myself as a social practice artist, but I’ve had many conversations with other artists and curators where it becomes part of the conversation. I think of it as an intersection between my creative practice and social practice on a spectrum. Artists are probably somewhere on that spectrum of social practice. For me, I’ve been interested in the mundane, the domestic, and the human experience, especially as it relates to my family, storytelling, and narrative strategies. That blurs the lines between my creative practice and my home life, where a lot of what you might call social practice originally occurred, where those lines are blurred. In addition to that, my interest in teaching, cooking, and sharing experiences with others has built up in a way, as well as the community work I’ve done. So now there are different areas where you can say the community work I do is social practice, or the projects where I mail postcards, letters, and other print material, they have a history in that kind of practice. The way I bring those two ways of looking at the world back into the studio ends up being a blurry place where those two things exist. It’s not always clear, but sometimes it fluctuates. Over time, it changes. When I was a young student making a lot of work, I didn’t think about it in relation to the social practice art movement. I saw it as a separate thing, with some intersections with performance and music. Now we have a different language and a lineage of artists coming out of social practice, especially in this city. It’s a bit clearer now. I wonder how I or others might conceptualize or contextualize the work, not just the work I’m making, but the work others are making, in 10 years time. It could become part of that canon or have an offshoot or something like that.

Kiara: Yeah, that’s a really good question, and it’s something to think about. Before I found this program, I wasn’t really aware of social practice either. I believe many people have the capabilities of being a social practice artist based on what they do in their everyday lives. However, they may not formalize their practices in that way simply because not everyone knows about social practice. But I do sense that attention around it is growing, and I’m excited about that too. When I think about social practice, it makes me think about inclusiveness. It feels like a part of the art world or art scene that is more accessible.

Jodie: Yeah. I think that’s another intersection that I’ve thought about for a really long time, which is that I’ve always wanted my work to be accessible to non-artists. I think a big part of that was because I wanted my family to be able to experience my work and not being an artist shouldn’t be a barrier to experiencing it, and understanding it. That doesn’t mean that the work itself can’t be layered and have more theoretical or intellectual themes and experiences and takeaways from it. I think that for me, it’s so important when I’m working with an idea to try to translate it in some way, through objects or whatever installation, that is accessible.

Kiara: Yeah. That makes me think about how earlier in the conversation you were talking about how you were speaking with Holding Contemporary, and you were thinking about the work that you were making at the time, you didn’t necessarily want to formalize your community work in a gallery space. Is that also talking about how you’re translating these things? How do you feel about your role as an artist and when you’re doing social practice projects or events with your community, and how do you formalize those things? What are some thoughts you have around authorship?

Jodie: Yeah. That’s a great question. When I’m doing community work or collaborative work, I’m not interested in authorship. I suppose in a way, it’s important for my collaborators on those projects to share that value. It doesn’t mean that it can’t be aesthetic or considered in those ways but there’s definitely something else to prioritize in those contexts. I worked with Amanda Lee Evans, for example, who had a big project called The Living School. She brought me into work with one of the youths that lived on the site. It wasn’t a formal mentorship, but it was based on the social practice program’s mentorship program. I ended up coming over to work with one of the youth there, Zira, weekly for months. For me, the relationship that we built together around being curious about art, cooking, talking and learning about her and what kids are into,that became the priority, and everything else kind of fell away. I didn’t need to document the work we made or the fact that we were doing this. I remember thinking that I could go through those processes, and that this relationship was also a project, but I didn’t think we needed any more pictures of an artist hanging out with kids. I’m also not one to take a lot of photos,. I think that’s a very specific kind of thing. But for me it’s so much more about experiences than it is about an image or a specific aesthetic or something that might be clearly “Jodi’s work.” When you look at all my projects together, you’re like, oh yeah, there’s an aesthetic at play here.

Kiara: There’s an aesthetic at play?

Jodie: Yeah. There’s an aesthetic maybe at play, but it’s not stylized.

Kiara: I feel the aesthetic could be the experience.

Jodie: Yeah. There’s consistency. Going back to the full school exhibition, people talked so much about how they felt in the space more than they talked about the objects. That didn’t to me mean that the objects weren’t powerful. It was all working together, but it really is so important for me to think about , what people experience and what they walk away with. And so there were so many decisions made in that show to really guide viewers through that. And so, even when you see a wall of a bunch of old stuff, at a certain point you’re not even thinking anymore about it being an art show or a collection of works or what is real and what is old. You start to recognize the feeling of experiencing somebody’s collection of things where the handmade stuff and the real old stuff blend in together at a certain point. And it doesn’t matter anymore because you transcend into experiencing the entire installation as one big thing.

Kiara: I really appreciate that description cuzI’m a visual thinker, so when you’re describing these things, I’m thinking about experiencing the pieces and going through that. I wouldn’t call it a separation, but, out-of-body experience comes to mind because it seems like you’re zooming out, and that it’s bringing in more thoughts and feelings that are not necessarily related to the object or art itself. But those feelings are coming out of that experience looking at this piece of work.

Jodie: Totally.

Kiara: Yeah.

Jodie: Off course I have an experience that I’m attaching to the objects and all of that. But again, there are so many visual cues that lead a viewer to, not necessarily interpretation, but just narrative, because I also think it’s, it is all about storytelling. I think that especially in this show, the objects are all about storytelling. There are lotto scratchers and tools that have been used, and other really handled objects, ceramics and clay that you have to handle and manipulate, so they have their own history. Everything is loaded with meaning and story. And so I’m guiding viewers into that. I’m welcoming them into that and guiding them through it.

Jodie: But I think the more meaningful things that can come out of it is how someone can be reminded of their own personal experience, and maybe their own experience with their elders. And I had a lot of people who were like, Oh my gosh, some of these objects reminded me of my father, my grandfather. Because they are not that special: there’s an old pair of pliers. And to me, those pliers are special because my grandfather held them and used them, but they’re also just anybody’s grandfather’s pliers.

Kiara: Yeah. It reminds them or it resembles something from their elders. Yeah. And I think you’re talking about storytelling, how the object has a story story in itself, but you’re also inviting the viewer to go through their own story by asking what memories are sparked from me looking at this object. And they’re going through that process of remembering. It’s that sentimental value. Although it is a common object, it’s able to spark sentimental value for viewers that are interacting with the work.

Jodie: Totally.

Kiara: Yeah. Definitely. This is my last question. Are you working on anything currently that you can share?

Jodie: Oh I’m always working on a bunch of stuff. It’s not all finished, but I had a show in Santa Rosa. I got that work back pretty recently, and so I’ve been unpacking that and figuring things out. I am also going togo back to that similar area in Northern California for a residency later this year. And I’m working on another publication. And I’ve been kind of working on this project in the background for a while now, I guess years now because, you know, the pandemic has warped us into years now.

Kiara: Yes. Definitely.

Jodie: But it is a book that has recipes and prompts and invitations.

Kiara: Hmm. Is it tapping into your interest in Flexis?

Jodie: In some ways, yeah. But it’s also related to the fragment of remembering

Things. Like how a lot of the domestic kinds of tasks that my grandmothers did and what I remember and don’t remember from that time. So it’s in the middle state. It’s not in the beginning cuz I’ve been working on it for a while. But I’m gonna be able to spend some time out at this pretty cool residency and they actually have a really nice cooking setup. So I think what I wanna do is focus my time more on some of the actual food projects that might be included in it. Cuz I have a lot of the other more poetic gestures that might be included. And I need to buckle down and get some of these more practical, straightforward recipes down on paper.

Kiara: That sounds really exciting. I just love and appreciate the fact that you’re creating work for your grandfather and now you’re creating work for your grandmother’s grandmothers, and I think that’s really beautiful. I’m excited to see the publication.

Jodie: Yeah. Thanks. We’ll see what it becomes. I’m excited to spend some uninterrupted time and really turn it into something.

Kiara: Definitely. Yeah. Well, let me know.

Jodie: Will do.

Kiara: Thank you so much for your time.

Jodie: Thank you.

KIARA WALLS (she/her) is a social practice artist, educator, and dean residing in Portland, Oregon. She holds a Bachelors of Art in Graphic Design from California State University of Northridge and a Masters of Fine Arts in Art and Social Practice from Portland State University. Walls’ work explores the layers of Black sovereignty through creating conversations, film, and site-specific installations. Her practice often involves community engagement and collaboration, inviting participants to join in the creation of the work. Walls seeks to engage in dialogue and reflection on themes related to trauma, identity, healing and intimacy. In her project, “The Black Box Experience Series”, Walls’ invites audiences to join the conversation around “What would reparations look like today?” through stepping into an experience other than their own. Walls has completed residencies at Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles, California, and Sunset Art Studios in Dallas,Texas. She was awarded the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art Precipice Grant for her collaborative project “Kitchen”, which explores the relationship between hair and intimacy while centering the experiences of Black clientele and natural hair practitioners. Walls seeks to challenge and disrupt systems of power and oppression while empowering and elevating the voices of marginalized communities.

Jodie Cavalier (she/her) is an artist, educator, and artist administrator living in Portland, Oregon. She earned a BA from the University of California, Berkeley and an MFA from Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland, Oregon. Her work has been exhibited with Converge 45’s Portland’s Monuments & Memorials Project in Portland, OR; the Schneider Museum in Ashland, OR; the deYoung Museum in San Francisco, CA; the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, CA; CoCA in Seattle, WA; Practice in New York, NY; and Städelschule in Frankfurt, Germany; among others. She has participated in residencies such as ONCA in Brighton, England; the Center for Land Use Interpretation in Wendover, UT; Wassaic in Wassaic, NY; and AZ West in Joshua Tree, CA.

Việts on Venus

Text by Lillyanne Pham with Kim Dürbeck

Lillyanne Pham with Kim Dürbeck

The influences came from my own upbringing and what I experienced myself. Vietnamese people are so strong in “doing it our own way.” I guess it brings a lot for us to see and laugh about that.

-Kim Dürbeck

I’ve focused on offline place-based cultural practices in my past interviews; nevertheless, a large part of my art practice interweaves online and offline neighborhoods. For my last interview this school year, I wanted to highlight the power of digital cultural work, specifically an online neighborhood special to my heart; @vietnamemes__, created by Kim Dürbeck in 2017 on Instagram. Kim is a Norwegian-Vietnamese creative who has brought worldwide Vietnamese communities together through music and memes. The following interview expands on the impact of, the values behind, and possibilities of his memes.

Lillyanne Pham: How did @vietnamemes__ start and how does it function or where does the content come from?

Kim Dürbeck: I started doing memes because I used to work the night shift. It was very boring and I guess I had to be creative. I was chatting with my friend and I decided to make a meme to send to her. It was this meme; my very first meme.

It combines a trend “Netflix and Chill” with a Vietnamese legacy “Paris by Night.” I guess we all have “Paris by Night and Chill.” We all, as Vietnamese diaspora, grew up with the show and we know, “Netflix and Chill.” It kind of makes you feel like home in trending humor. I was very strict about not making fun of us as Southeast Asians, as most memes used to be back then. Humor like… “Only straight A students are Asian” or “All Southeast Asians are doctors and lawyers.” I wanted to focus on nước mắm, all the beautiful culture we have, and then present and combine all the richness of our culture in a Western world.

Lillyanne: Here is a photo of my mom’s reaction to one of the memes you posted. I regularly send them to her but she doesn’t always get it. As you can see, she “disliked” it. What have been the various relationships you’ve made through the memes? What kind of conversations are created around the memes?

Kim: I connected with many Viets who grew up around Europe. We connected because most of us were children from refugees. We all were in the same situation – parents coming to a new country having to start their life over again. Kids being bullied for being different. Everything on a budget. The struggle with growing up with trauma, PTSD, parents yelling at you, social control, different levels of assimilation, violence, saving money, and of course, combining our food habits with everything. Nước mắm all everything.

These topics were the beginning. I started only to get followers from Europe. A lot of people texted me and wrote that they could see themselves in the memes. This encouraged me to go forward and keep making memes. A lot of people texted me like, “Hello, I grew up in a small city outside (a capital city) and I was bullied,” or “My parents never understood me. Thank you for sharing memes. It makes me feel less lonely and understand my culture,” or “It makes me understand,” or “Cherish my culture even more.”

I guess I could find the similar pattern in our second generation by just referring to my own third culture or upbringing. I started to reach an even bigger audience when people started sharing. I reached Paris, Berlin, Canada, America and so on. I even chatted with the Vietnamese diaspora in Latin America and Iceland. Then jokes were, “OMG do you have nước mắm on tacos over there?” or “Iceland is so cold the nước mắm is always frozen around here!”

Then I hit another audience–Vietnamese students studying abroad; a whole new generation of lonely Vietnamese students texting me, “I miss Việt Nam so much and I am here all alone and I can’t go home,” because of Covid or economic reasons. Vietnamese students developing their identity abroad.

Many of these Việts also discover musical or art culture abroad. And I was combining music and memes where I often reach creative Vietnamese people. I try not to use too much of a commercial approach because I want to support the Vietnamese people who don’t get a lot of support from home because their parents never understand what they want to accomplish. For me, it’s very important to be yourself no matter what kind of culture you grew up with. Like, if you are Vietnamese, you could get pushed into studies you really don’t want to go for. Or these unwritten norms about how a Vietnamese person should be. I think it is important to support people to break out of the stereotype and go for alternative art, music or business. I think the humor and memes make this clear subconsciously or obviously, and maybe people can find themselves in the humor that also motivates them to go their own way for personal development.

I used my platform (@vietnamemes__) to discover and promote these individuals. This inspires and motivates more people in either fashion, modeling, music, art or food. I think it is a duty we all should have to support each other and our Vietnamese worldwide community.

Lillyanne: As a traveling artist actively researching different Vietnamese diasporas, what has impacted you most on your ancestral journey?

Kim: As a traveling artist pushing modern Vietnamese culture, I met a lot of people supporting the memepage and community. I was recognized in the streets and in the stores for my meme page and they often mention my music as well. I’m sure my music got more attention because of the meme community. I also developed some kind of aesthetics around the memes. And the way I post combined with my music– I started to get connections and invitations all over the world.

I also push Vietnamese electronic music in my stories and in my videos. So, other Vietnamese people can discover that, if you are Vietnamese, growing up like we all did, going for your dreams, you are not alone. People found each other, started working together, or even building each other. For me, it was so nice to see that there are so many like me all over the world. We understand each other. I think we have been longing to be understood; therefore, we support each other and end up working together somehow. For me, the art of music and DJing has been my platform. So many talented Vietnamese artists that I never would have found if it wasn’t for the community.

Lillyanne: How do technologies (digital or not) fit in your ancestral journey?

Kim: Social media has been everything. I know most Vietnamese people in Việt Nam use Facebook. But, if you are a little more curious, or from the newer generation, they choose Instagram and the next generation, TikTok. Digital has been the ultimate tool to build this community. I don’t think I would reach this level without digital tools. I think I was right on time to make @vietnamemes__ on Instagram when I think about how our second generation grew up and dived into Instagram. There will probably be different platforms where they need a community in the future. Maybe, there will be a metaverse Vietnamese community in 3D in the future where we sit on the floor eating dried squid and listening to Cải lương techno. Who knows?

And humans can’t live on Earth because of nuclear war. So humans travel to different planets. And the Vietnamese human diaspora choose Venus because it’s cheaper and you can grow herbs and fish much easier because of the weather or something. And Venus always has grocery sales in the supermarkets. Maybe Venus becomes the next Vietnamese planet just because Việts adapt so well.

But, without having to joke about this galactic Việt diaspora, I can say that digitally I have connected. Physically, I have traveled to various countries and met people just like me with the same upbringing. We ate together and talked about the same challenges we all had as the Vietnamese diaspora: how hard it can be to understand our parents’ mental health and our mental health and then try to make it work for everybody, how food is our love language and sometimes money but not talking about feelings, how people were bullied in elementary school or at work for being different, or topics about how hard it can be to be gay, or just talking or learning about sex in the Vietnamese community.

After a while, I combined my memes with pictures from google and then people started sending me memes to make it grow bigger. I have a combination of people sending me and creating memes from pictures I find online. Sometimes, I add a funny text or just the picture speaks for itself.

Lillyanne: When I see your memes, I know the references. They are on the tip of my tongue. I often think about how I never would’ve been able to make these connections in one meme. I grew up for eighteen years in a small town without knowing much about Vietnamese people outside of my family. Now, I live in the largest Vietnamese population in the US. But how I experience my culture is always hard for me to explain. What/Who/Where are your influences in shifting Vietnamese humor and music before you started making? And also your influences in your practice?

Kim: The influences came from my own upbringing and what I experienced myself. Vietnamese people are so strong in “doing it our own way.” I guess it brings a lot for us to see and laugh about that. Maybe we think it’s funny because we have both of our feet in the Western and Vietnamese culture. For us, we see a washing machine on a motorbike and we’re shocked, but for them it’s just moving a washing machine. I also follow a lot of Vietnamese accounts because in the beginning when I started the meme account I followed all Vietnamese people I could see on Instagram.

Lillyanne: I love how you talk about being basically a digital cultural worker, shifting how memes are produced about us and how humor can expand conversations on so many levels of our lives. Was this always your intention or did you discover this part of your practice during the process? Do you have plans to grow or change your meme and music practice in the future? Are you experimenting with other mediums or ideas?

Kim: I would say it changes all the time with the trends. My music also changes through time, it has happened before. Yes, I would say that I discovered this part during the process.

Kim Thanh Ngo aka Kim Dürbeck, Born 5 of October 1986. Norwegian-Vietnamese producer, composer and practitioner based in Sandefjord, Norway. Co-runs independent record label LEK REC based in Oslo. Play and produce electronic music like Ambient, urban club music, Experimental club music and scoring commercials or theater.

Lillyanne Phạm (b. 1997; LP/they/bạn/she/em/chị) is a cultural organizer and artist living and working in so-called East Portland. Their personal work centers on ancestral wayfinding, nesting, and communicating. Her current collaborative projects are a queer teen artist residency program at Parkrose High School, a canopy design for Midland Library, and a youth program at Portland’5 Centers for the Arts. LP’s work has been supported by Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon, Mural Arts Institute, the Regional Arts and Culture Council, Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, the City Arts Program – Portland, and the Dorothy Piacentini Endowed Art Scholarship. For more work visit: https://linktr.ee/lillyannepham

Social Practice is Gay and Being Gay is Social Practice: The Art And Social Practice Archive in Queer Context

Text by Olivia DelGandio with Caryn Aasness, Lo Moran, and Marti Clemmons

“I think queering history is essential, especially since people are trying really hard to erase us from existence. We need to continue to place ourselves and what we believe in into our work.”

-Marti Clemmons

Every Tuesday for the past three terms I’ve spent a few hours among the Art + Social Practice Archive at the PSU library talking to Marti Clemmons and Caryn Aasness about archives, queerness, and the inherent queerness of archives. Here’s a conversation we had on the topic with one of the founders of the A+ SP Archive, Lo Moran.

The Art + Social Practice Archive was founded in 2018 by Shoshana Gugenheim Kedem, Roshani Thakore, Lo Moran and Harrell Fletcher, and with the help of Cristine Paschild and Marti Clemmons from Portland State University’s (PSU) Special Collections and University Archives, to mark the 10th anniversary of PSU’s Art and Social Practice MFA program. Located in the Portland State University Library Special Collections, the Art + Social Practice Archive is the first public archive dedicated to socially engaged art ephemera. The ASPA houses both physical and digital materials including posters, publications, flyers, zines, videos, sketches and other project documentation from past and ongoing artist projects.

Olivia DelGandio: I’m thinking about a conversation we had when Caryn and I first started working at the Art and Social Practice Archive with Marti. We were really into the idea that archives are inherently queer. I don’t know how this conversation started but we were like, it’s obvious that this is queer. What do you think about this idea?

Caryn Aasness: Maybe because we’re still at relatively early stages of social practice as a field of art, it feels like it has a sense of queerness to it. We’re kind of bending the rules and making something new here. In the archive we get to acknowledge multiple perspectives that are underrepresented in western art history and it holds such a variety of stories so it’s going to be a more accurate picture of what’s actually happening, who is involved, and what’s influencing this field.

Olivia: Totally. Living a queer life means questioning things and thinking about alternative futures. I feel like that’s what we’re trying to do with the ASPA; we’re making the rules and queering traditional structures of archiving. This space didn’t exist until recently and now that it does we’re gathering and putting material into the world to make them exist in the present so that they can continue to exist in the future. And I think it’s so gay. Also, look at us as a group of people involved in this project right now; if everybody involved in the archive is queer, the archive itself is queer. We’re putting so much of ourselves into this project even though what we’re actually doing is collecting other peoples’ things.

Marti Clemmons: I wouldn’t want it any other way. I think when I first started volunteering and

working at the City Archives and the Oregon Historical Society, I was very much afraid to place my identity in my work. As a student in the History department, I learned you keep yourself out of your work. But now if I see the words “queer” or “gay” in the materials I’m working with, I’m making sure that it goes in the finding aid, because historically that is not acknowledged. Any chance I get to put queerness in the collections, I do it, and I will continue to do so.

Caryn: Making the future. Yes.

Lo Moran: I’m thinking about the ethos of social practice; it’s about valuing things that are undervalued in our current systems and having trickster energy in your artistic approach. I feel like that is a theme, drawing attention to everyday moments or stories that weren’t traditionally paid attention to, and that is what queerness is all about too.

Marti: I think the work that we’re doing, not to toot our own horns, but it’s very

important. I think queering history is essential, especially since people are trying really hard to erase us from existence. We need to continue to place ourselves and what we believe in into our work.

Caryn: I feel like people have always inserted themselves into the history and the work that they’re doing, they just weren’t acknowledging their identity and what that meant. You have to acknowledge where you come from.

Olivia: Being a social practice artist also means putting all your different identities into your work. Thinking about the work in the ASPA, the breadth of projects is so vast, because all of our identities are in our work. WAnd we can’t separate our identity from the work we want to be doing. Caryn, your work is so much about how your brain works and you put your brain into every project you do. MAnd my work is so much about grief, and I put all of that into every project I do. These projects are archiving our identities and the people that we are at this point in time. I think this connects to queerness too because we can’t separate this major facet of our identities from the work we’re doing.

Caryn: There is so much generosity in putting your identity into your work and allowing audiences to see into your personal experiences. It just makes things richer.

Olivia: It just feels like social practice is gay and being gay is a social practice.

Lo: I think we should end there. That feels like a good ending.

Lo Moran (they/them) creates interdisciplinary projects that are often participatory, collaborative, and co-authored. They aim to experiment with and question the systems in which we’re all embedded by organizing situations of connection, openness, and nonhierarchical learning. Lo desires to develop sites for accessibility, and reimagined ways of being together. They are currently living and working in Berlin, Germany.

Marti Clemmons (they/them) is an Archives Technician at Portland State University’s Special Collections and University Archives. They are interested in using archival work as a means of activism, especially through a queer lens.

Caryn Aasness (they/them) is a queer disabled artist from Long Beach, California living in Portland, Oregon. Caryn wants to invite you into their brain. In it we explore mental illness, and the folk art of coping mechanisms. We investigate queerness and how it forms and severs multiple selves. We look to language and learn how to cheat at it.

Olivia DelGandio Olivia DelGandio (they/she) is a storyteller who asks intimate questions and normalizes answers in the form of ongoing conversations. They explore grief, memory, and human connection and look for ways of memorializing moments and relationships. Through their work, they hope to make the world a more tender place and aim to do so by creating books, videos, and textiles that capture personal narratives. Essential to Olivia’s practice is research and their current research interests include untold queer histories, family lineage, and the intersection between fashion and identity.

The Interview is Only as Good as the Relationship

Text by Marissa Perez with Ruth Eddy

“Listening. That’s the number one thing.”

-Ruth Eddy

This is an interview about interviews. I don’t think I’m a good interviewer and Ruth is the best interviewer I know, so who better to ask my burning interview-related questions? When I first met Ruth, she was writing a story about a business called “America’s Noodle” for her neighborhood newsletter. I was impressed by her curiosity and her boldness in going to talk to the people at “America’s Noodle” and I wanted to be just like her. Now, it’s five years later and I still want to be just like Ruth.

Ruth: First, I wanna look up what “interview” means. Like, what’s the definition? Here it is: “A meeting of people face to face, especially for consultation.” Hmm. Yes. Interesting. A structured conversation where one participant asks questions and the other provides answers.

Marissa: There we go. That’s a good one. Because I was just thinking about how this kind of interview is different from a job interview, you know, but they’re both interviews.

Ruth: Wow. I don’t know why I’m immediately having so much fun, thinking about the definition of interview. But it’s hard to know, especially because you are also my friend and I have conversations with you and we ask questions and give answers in those conversations too.

Marissa: That’s cool. I wonder, though, because the definition was when one person asks questions of another, but I wonder can it be people interviewing each other? Can people interview each other at the same time?

Wow. Yeah. But then, is that just a conversation? Does an interview need a power dynamic a little bit? Or roles?

Ruth: Yeah, I think you’re right. This is so funny because I feel like having this conversation slash interview with you makes me feel so good. I think in some ways interviews can be more comfortable because they’re structured, but then they can also be so much more rigid.

Marissa: Ok then, the first question is, what is one favorite question you like to ask people? Which I realize is a hard question.

Ruth: I think I actually know this.

Marissa: Oh, yeah?

Ruth: Well, I guess I should shout out to Anna Deavere Smith. Is that her name?

Yeah, Anna Deavere Smith wrote a book called Talk to Me, and she’s a theater lady. She was an actor who would interview people and then perform as the people she interviewed, like monologues.

Her whole thing was getting the essence of a person. Through speech, I guess. And she said that there are three great questions to ask. I think one of them is where were you born? The next one is, have you ever been close to death? And I can’t remember the third one. I think that those are hard to get into, but I do find myself asking people a lot where you were born. Sometimes we say, where did you grow up? Or, where are you from? And those things can be hard to get into like a conversation around.

Where were you born feels just like a great starting place, because we were all born.

Marissa: Yeah, it’s a good question because it’s an easy question that leads to more questions. Okay. Question number two. What do you think makes an interview good? When I read that question out loud it sounds weird, but it’s the question.

Ruth: Okay, well now this is gonna get really meta, because what if what makes an interview good is when you can also ask questions? And so then I ask you, what do you think makes an interview good?

Marissa: You’re setting the terms and then using them to say that what makes an interview good is me getting to say whatever I want, so I’m gonna say whatever I want…but that wasn’t your answer. Yeah, I don’t know what makes an interview good. Because there are different angles. I’m critical of the question now, because I’m wondering “good” for who?

Ruth: Yeah. And like we were saying at the beginning, there are different types of interviews too.

Marissa: Yeah. We kind of know the rules for a job interview because there’s a goal, you know?

Ruth: And what makes that interview good? It’s probably different from this interview.

Marissa: Okay. Question number three. Who do you want to interview the most? I guess it’s another way of asking, who are you curious about right now?

Ruth: Okay. The first person that comes to mind is Justin Bieber. And I feel like that’s been my answer for a while. I don’t know why.

Marissa: How long is a while?

Ruth: Years.

Marissa: Yeah. He’s changed over the years.

Ruth: I know. I think it’s something weird, and this is why it feels embarrassing, because it feels like that’s more like some reflection of me as an interviewer. It’s because Justin Bieber’s at the top of some access pyramid. Along with the president, but I would rather talk to Justin Bieber.

Marissa: Maybe that’s the answer to a different question too, which is: if you could interview anyone, who would you interview?

Ruth: Yeah. Yeah. But what is the question though?

Marissa: Who do you wanna interview the most right now?

Ruth: I don’t know. I think maybe for someone outside of my world I would need more of that rigid structure, like an interview, whereas the people I wanna talk to are just people that I see around. Like, I would maybe want to interview my postman, but I feel like I don’t want that dynamic between us. I’d rather just have a conversation.

Marissa: Asking someone to interview them sets up a certain dynamic, which sometimes you don’t want, because you just want to relate in the roles that you are already in. But there might be a reason if you’re like, “I want you to come on my radio show,” then there’s a reason to change that dynamic. But when there isn’t, it can feel kind of bad.

Ruth: Yeah, and I think I need to remember that like, I made my radio show to have that reason, but it still doesn’t feel like enough. Okay. Um, what was the question? Did I get it? Justin Bieber. You got it? Justin Bieber.

Marissa: I’ll listen to it later and either I’ll include everything we said or I’ll just include Justin Bieber.

Ruth: The power of editing.

Marissa: Next question is, do you have any advice for me as a novice interviewer compared to you, Ruth, an experienced, mature interviewer?

Ruth: Well, this interview is going great.

Coming up with questions ahead of time is great. A lot of times you want to see where the conversation goes, but as an interviewer, it is good to at least prepare the questions beforehand. It’s also good to abandon them as necessary, which I think we’ve already done.

I kind of wanna say, you don’t have to say, “Question number three, next question,” but I’m also kind of enjoying that right now. So I don’t know how I feel. I think you totally know how to be a great interviewer. Advice… listening. Listening. That’s the number one thing.

I think sharing a little bit about yourself is important. And maybe that’s where these roles are inherent to the interview structure, but also a good interview is going to be based on your relationship that you have with someone.

If it’s someone that you already have a relationship with, then probably the interview will be better. If you don’t have a relationship or not a big relationship with the person you’re interviewing, I think it’s important to try and build a relationship upfront and whether that’s just getting through technical difficulties or just having a little chit chat about yourself to build a better relationship because the interview is probably just as good as the relationship.

Marissa: What do you think about silence? I feel like you’re good at silence.

Ruth: …(silence)…

Marissa: You can’t answer it in silence. It’s an interview.

Ruth: I’m doing it. This is representative.

I guess I have two thoughts on that. Especially interviewing for audio, which is my area. I’ve really gotten better at nonverbal communication, which is basically just nodding instead of saying mm-hmm, or all the other things that we usually say out loud. Being able to do non-verbal communication while someone is talking shows that you’re listening without your voice being heard. So I think practicing non-verbal communication is great if you’re trying to record an interview. It’s also a good practice that allows for silence because silence can be uncomfortable only when it feels like there’s a disconnect and you’re like, “Are you hearing me? Can you hear me? Are you paying attention?” And if you can communicate in other ways, like with eye contact or with nodding, that you’re paying attention, then the silence can exist and not be uncomfortable. And usually that gives time for someone to think and then they can share a new idea that they came up with when they’re just being quiet and thinking.

Or it could just be silent. I don’t know. Silence is cool. Makes me just wanna be quiet now.

Marissa: I know. Now I’m nodding and being quiet more.

Ruth: Okay. There’s another thing about silence and audio recordings, especially when you’re doing an interview that’s going to be edited. You are tasked with gathering what’s called room tone, which is just the sound of a room, because every room you’re talking in is gonna have a different sound, and so you wanna have like two minutes of silence in the room, which is always hilarious.

Marissa: Do you do it at the beginning or at the end or both?

Ruth: I think usually I do it at the end, but now that I’m thinking about it, it feels like it could be good at the beginning too, but it definitely is too weird I think to do at the beginning.

Marissa: Okay. Oh, this is kind of changing the topic, the question is… we talk a lot about time. Have you had any new thoughts about time or seen any good clocks?

Ruth: Okay, this is like a great interview question because you know about our relationship. It shows that you know who I am and what I like to talk about.

I’m always seeing good clocks. And, I mean, it’s spring. I feel like more than anything, this feels like the time of the year where I feel most like connected to time, like in the biggest way possible, just like cycles of life.

Marissa: Well, right now in Portland, it’s the time where it’s like, here’s the next thing blooming and the next thing blooming and the next thing blooming.

And that can stress me out. Because I wanna see it all, and I don’t wanna miss a thing because everything’s so liminal. In winter the branches are going to be bare and tomorrow they’re still going to be bare.

So I haven’t been thinking about time, but I think I’ve been feeling it, you know?

Ruth: Yeah. A plant can really just come up overnight or bloom.

Marissa: Is it warm there?

Ruth: It is. This weekend spring was unlocked. It was in the seventies this weekend. And the trees have buds. Things are happening.

Marissa: Okay, last question. What would a dream radio show be? Or what’s a radio show you’re dreaming about right now?

Ruth: This is exciting because this is what I love to talk to you about, just my dreams, and then figuring out if they’re good ideas or bad ideas by saying them out loud to someone else.

Um, okay, so I have a radio show today. And I’m kind of excited because I think I have a map of what it will be and I want to include some voicemails that I got. I went biking in Yellowstone and right in like the middle of the park there was this payphone, but it actually wasn’t a payphone, it was a courtesy phone, which means you can make local calls for free, and I think local is defined by the area code and the whole state of Montana is in one area code.

So I called my own radio show and left a voicemail. And then I really wanted to put a sticker up because the booth was covered with people’s Instagram stickers or whatever. But I didn’t have a sticker with the phone number on it.

But then I hung around there and some other bikers came by, and then I wrote the phone number in the snow. So I think I got like two voicemails from the courtesy phone in the middle of Yellowstone National Park that I wanna play.

Marissa: From the phone number you wrote in the snow?

Ruth: Yeah. So I wanna play those. And then yesterday a friend came to visit and we drove out a ways, just up into the farmland and mountain lands to this spot that Eben used to go to as a teenager, this abandoned homestead. And I was recording audio there. It was very windy and I kind of like wind because it feels like it bends the rules. Wind is supposed to be the audio recorder enemy, but it’s also such a good sound. It’s like, let’s just play the wind, let’s really listen to the wind. So I wanna play a bunch of wind and this interview with Eben, my friend, in this abandoned house that he used to go to.

And I also just wanna give a shout out to you because when I was in this abandoned house recording yesterday, the way that I phrased it was not “Can I do an interview?”I used a phrase that I think I got from you, which is “Can you give me a tour of this place?”

And that felt so nice to be anchoring it in space. And I wanna do that more. So that’s a dream.

Marissa: Yeah. And I like that. It’s more like, let’s talk about this thing together. Or let’s talk about this place together and you walk me through it, or let’s go on a walk or, can you show me?

Ruth: Yeah, I think I would like to try and maybe do that more.

And I was just gonna end this interview, but I wanted to say I found the questions. Okay. So the three questions from Anna Deavere Smith are: have you ever come close to death? Do you know the circumstances of your birth? And have you ever been accused of something that you did not do?

Ruth Eddy (she/her) is the host of Radio Hangout on www.KGVM.org Tuesdays 5-6 MST . She is a collector of sounds and trash, lives in a tiny shiny trailer and produces podcasts in Bozeman, MT. www.therutheddy.com

Marissa Perez (she/her) grew up in Portland, Oregon. She is a printmaker, party host, babysitter and youth worker. She’s interested in neighborhoods and the layers of relationships that can be hard to see. Her dad was a mail carrier for 30 years and her mom is a pharmacist.

How an Artist Needed to be an Entrepreneur in Cambodia

Text by Midori Yamanaka with Lyno Vuth

“It has been really starting something from scratch.”

-Lyno Vuth

I met Lyno Vuth in Sapporo, Japan in 2016. He was invited to an event called Art Camp to present his work and I helped with his presentation as an interpreter. He shared how he and his team started an art workshop and artist residency in one of the historical buildings in Cambodia; it was called the White Building which was then gray because of the dirt and aging. The White Building used to be a symbol of modern Cambodia, but it became a low income residence after the Khmer Rouge. Sa Sa Art Project started there, surrounded by communities who have almost no idea what contemporary art is.

One day, when I was thinking of applying to the Art and Social Practice MFA program at Portland State University, I thought of Lyno, googled his name, and found Sa Sa Art Projects. It had grown into a sort of institution with projects and workshops and young artists. I was blown away by how much Lyno and his team had done.

Midori : You started the Sa Sa Art project in the White Building, and then you moved to the current location in 2017, correct? How long have you been working on the Sa Sa art project?

Lyno: For thirteen years now. The first six years were in the White Building, and then seven years in the current building.

Midori : That’s amazing! At the conference in Sapporo, I remember you mentioning that there was not much contemporary art education available in Cambodia.

Lyno: It was quite limited. For example, there is only one state art university, and the department is fine arts, but they are quite traditional, mainly doing paintings and sculptures. They are not so keen on contemporary and experimental practice.

On the other hand, there is a very big school in the north of Cambodia, Hmong, and in Paramount province. It’s not a state school, it’s a nonprofit school.They have had a long running art program since the nineties. Many students have graduated from there. Their program started out as informal but has evolved to a more structured four year program. And that opens for contemporary practice very much. And other than that maybe not so much, and that’s why Sa Sa is offering to fill this gap of contemporary art education.

Midori: How did you become interested in art?

Lyno: It’s quite a long story, but maybe I can share some key points. I was born in 1982, which is three years after the fall of the Khmer Rouge in 1979 so Cambodia was going through a transition.

It was still like a civil war and recollection of powers between parties. It was not until 1991 that the Paris Agreement was made to reconcile and not until 1993 that we had a new constitution of democratic state with multi-party parliament. So in a way, because of that political infrastructure, it didn’t allow contemporary art practices to prosper.

It wasn’t until the late nineties that a new important art space called Radium: Arts and Culture Institute opened. Some other spaces slowly launched among Phnom Penh, including the French Cultural Institute which promotes art exhibitions that brought in French and Cambodian artists.

Midori: I see.

Lyno: For me, growing up around that time, I didn’t know much about art. I actually studied information technology, but my interest was quite a lot in the visual aspect. Later I was working in a nonprofit and then I became interested in photography.I would go into galleries by myself. At one point, I found out that one photo gallery offered classes. That space allowed me to meet others in the community and after graduating we tried to stick together.

That’s the beginning of this project journey, we formed the collective with the idea of wanting to do something to contribute to the landscape of contemporary art and to also allow us to continue to be artists.

When the Reyun came to an end in 2009, it felt urgent to build a Cambodian run space and we wanted it to be independent even though we didn’t quite have the skills to do it yet.

So , one thing led to another. In my practice, studying photography evolved into curating by necessity…and because within Sa Sa, we had to do sales… so it’s like skills that I had to learn as we go until today. It has been really starting something from scratch.

Midori: I see. That was the moment you became an entrepreneur!

Lyno: I am not sure if entrepreneur is the right term. But long story short, we had opened one small gallery already around 2009.

We tested with that gallery and then we expanded into the idea to be more of a space for education, experimentation, exchange, and learning.

Midori: Wow.

Lyno: Yes. There was a moment of energy coming together.

Some of my collective members were from the universities, and they just graduated. So we were eager to continue doing something. Also we had a leader, a former team member who was a self-taught photographer. He had developed his practice, and he helped us to become ambitious and to come together.

Midori: Also during that period, you went to the States to study for your master’s degree.

Lyno: Yes, I studied in the US from 2013 to 2015. It was a turning point in my life, because when we started the Sa Sa Art project, I was still working full time in the nonprofit. So, applying to school in the US was like another part time job for me.

I did not know where the funding for the art in Cambodia was. There is zero funding for contemporary art from the government. So we need to think about getting it from somewhere else. I knew nothing.

Fortunately, we were able to meet good collaborators along the way.. We got a small grant and we did a series of workshops in photography and mixed media with young students from the White Building neighborhood.

Over time, we maximized the potential of the workshops and got to know our neighbors. There was a conversation and presentations at the end and students invited their families and the neighborhood to come and see. People were so excited, so happy and proud.

I asked them what they wanted to do after, and many of them said they wanted to study more. I was like, “Oh, they want to study more! But what do I have to offer?” Then I realized that this was my calling. That’s something I need to really put my full energy into. I needed to put my full energy into learning and my own growth and development. So I decided to pursue this master’s degree in the USbecause there’s no program like that here in Cambodia. I got scholarships and everything came into place.

When I came back, I continued to think about the way we teach and being an artist and curating.

Midori: How was your experience being in a school in the United States?

Lyno: Oh, it was so hard. The language and terminology, and the compensation of the academic material… I would read one paragraph and boom! Everyone else in the class had already read and finished the discussion. So it challenged me a lot.

It really pushed me so much. I was like, “Oh my God, can I do this? (I don’t think I can!)” But, you gradually get used to things , and hang on to it… and somehow survive. It really changed my life.

It really opened up my perspective in the ways that I look at my home country. I look at what’s happening, what happened before, how can we learn from that, what can we do now, and what I find I really appreciate a lot is to look at those things with a critical lens.

I think that the MFA program helps me regardless because it is a history of mostly European and American art. There are some other classes that involve art from Asia as well, but not a lot. I think it helps me to develop a method and a discipline in my thinking, in my writing and in my attitude towards things regardless of whether it’s art or not.

Midori: We need to update art history with more content from other cultures and countries.

It’s not easy for people from other countries to study in the United States in English when it’s not their first language, but I assume there must be so many more challenges when you return to Cambodia.. What was the biggest challenge you faced?

Lyno: I am not sure if it’s a challenge, but at the same time it is an opportunity as well. Thinking about the Sa Sa Art Project, when I came back in 2015, we continued to work at the White Building but also at the same time,we heard from the government that there was possible demolition and eviction.

We wanted to think about what we would do if they all agreed to move. If they did not agree, we would stay with and we would continue to look for alternative solutions. , But they decided to move.

There was also the conversation of, “are we still relevant?” and “Is our work still relevant outside of the White Building?” And if so, what are our strengths and do we want to continue? So it was a collective discussion and we all agreed that our strength is in education and that it’s something that we could continue to grow. We decided to continue in the new space. It’s grounded in an education program and it has also expanded into exhibition.

Midori: Wow. Amazing. So, is it currently funded by the Cambodian government?

Lyno: No, not at all. We were very fortunate to have an amazing funder fully support us for a period of three years from 2019 to 2022. Those three years allowed us to expand on our ambitions in the program and focus on the impact of our work. We were able toprepare and think through how we can be more sustainable and independent.

Midori: So it was privately funded?

Lyno: Yes, we were privately funded by this Japanese-owned foundation based in New Zealand.

Midori: Wow. I am kind of proud. Haha.

Lyno: Yes. That’s amazing. It was actually, in fact, after we moved out here, we were also draining our funding and things. So this funding came at a very critical time. So through which we were able to continue to survive, and at the same time to have this time not thinking much about making money for now, but thinking about making money for the future.

Midori: Right. So now are you guys able to sustain yourself?

Lyno: Agh….almost! Haha…not quite yet! We are reaching a point where we feel okay for one year and a bit difficult for one year.

From the year of 2020, we started this fundraising option. It’s quite amazing. Because after all these years, as you could see from 2010 to the networks that we have built connections with artists in residency program, with partners, with friends in Cambodia, in Southeast Asia, and far beyond that we came into a point where we were able to to ask artists to contribute an artwork to us for our auction.

And 50% go back to artists, 50% goes to Sa Sa Art Project. We started in 2022 and it went very successfully amidst the COVID crisis. Yes. And it was quite, quite interesting because we were learning along the way and because of the COVID. Right. So everything was quite new, a new system upgraded to be online through this new platform, new technology developed online, including online bidding and options.

Midori: I see that now! I hear you say challenging could be a possibility.

Lyno: We knew that there’s some resources available. If you’re talking about art buyers or collectors, there are very few locally who are doing it. So we know that we cannot rely only on the local art collectors. So we need to reach out to the regional art collectors.

An online platform is the bridge. At that time we were still acting, but it is also very important to have the local presence to engage with the audience here so that they understand a bigger picture about the art scenes in Cambodia. For 2020’s auction, we had about 80 plus artworks. We’ve actually got between 80 and 90 artworks as well for 2022.

It includes young artists who graduate from art class to more senior and established artists from Cambodia and to kind of like a range of diverse artists from South East Asia, largely. So in a way, we call it the auction exhibition.

Midori: So a physical exhibition while having an online presence, it’s like a hybrid.

Lyno: Yes. We know that it is important to engage with the existing audience here in Cambodia to have that presence. And so they can see the highlights of Cambodian contemporary art and artists from the region. Also a sense of solidarity, while at the same time having an online presence for the regional art collectors that we reach out through all our networks, possible networks.

Midori: That sounds great. Wonderful!

So you had 80 to 90 pieces of artworks. Did you sell all of them or how did it go?

Lyno: No, we did not sell all of them. with 20, 21 days. I think we sold only about 10%, 25% of the artworks. But with strategic high value in combination of established artworks for the original act and low value adverts for the local and affordable for the local collectors,

Midori: Wow. You guys funded more than $40,000.

Lyno: Yes, that is the one from 2020. That’s quite remarkable and we are very thankful. For example, like the funder that used to support us for three years continues to support us through auctions.

Midori: Wow. Nice. Congratulations!

Midori: This is my last question for you today. How would you encourage children who are interested in pursuing art? What would you say?

Lyno: That is a hard one. Haha…

Whenever I teach, at least in my class, I want to know where you are from. To know who were in the way cultivated before you. Learn from strategy. And have a question for yourselves. Learning from the past, achievement, and innovation. What can we learn from? Learn from those and take action for now and future. For yourself, for your community, for your context.

Lyno Vuth (he/him) is an artist, curator, and educator interested in space, cultural history, and knowledge production. Alongside his individual artistic practice, he is a member of Stiev Selapak collective which founded and co-runs Sa Sa Art Projects, a long-term initiative committed to the development of contemporary visual arts landscape in Cambodia. His works have been presented in Cambodian and international venues including at major exhibitions and festivals such as the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Biennale of Sydney, Singapore International Festival of Arts, and Gwangju Biennale. He holds a Master of Art History from the State University of New York, Binghamton, New York, a Fullbright Fellowship(2013-15), and a Master of International Development from RMIT University, Melbourne, supported by the Australian Endeavour Award (2008-2009).

Sa Sa Art Projects https://www.sasaart.info/

Midori Yamanaka (she/her) is a social practice artist, educator, and single mother. Midori was born and raised in Japan, but is currently living and working in Portland, Oregon. Her practice explores ways to harness creativity based on common values in diverse societies and their respective cultures. She has been working on many international projects as a creative and cultural hub, including Virtual Playdate (2022), World Friendship Online (2020), Asia Winter Game in Sapporo (2017), Esin Creative Workshop in Sapporo (2015), and many others. In 2023, she launched a global mind creative coaching program for Japanese women. She holds a BFA in Graphic Design from Art Center College of Design, and currently is studying and practicing Art and Social Practice at Portland State University.

Getting to Know Each Other While Doing Things

Text by Diana Marcela Cuartas with Chemi Rosado-Seijo

“We are artists who immerse ourselves in social issues and do things that can go well or go wrong. Many of us who work this way don’t do it only for the intellectual class or for people with money that can support our work. In fact, because of the interest in social commitment, we decide to deal with all these structures because they can mutually benefit. I wholeheartedly believe in those exchanges. There is fundamental knowledge in each social group that ought to be connected.”

-Chemi Rosado-Seijo

Chemi Rosado-Seijo is a Puerto Rican artist and skateboarder who has created some of the most iconic art and community action projects in Puerto Rico. From painting the facades of an entire town in different shades of green, building a skate ramp/hang-out-spot by the sea, or changing the focus of the voices we pay attention to in the museum, his art invites a new understanding of a specific place and its people.

Chemi is also one of the first artists I learned of who considered himself socially engaged. La Perla’s Bowl and El Cerro illustrate how his practice embraces social engagement as a life-long relationship with participants and collaborators that stimulates social exchange, networks of support, and artistic thinking beyond the project’s specificities.

This conversation expands on some issues noted in We Did This–a previous interview with Jesús “Bubu” Negron, a friend and collaborator of Chemi, who also works in community organizing through art. Both artists have made significant contributions to the socially engaged art landscape in Puerto Rico, with a particular sensibility towards communities in their contexts and an understanding of engagement that questions the possibilities of this artistic practice inside the larger art world and its institutions.

Diana Marcela Cuartas: I was introduced to your work by hanging out with Bubu Negrón1, and I would like to know how you see the relationship between hanging out and socially engaged art.

Chemi Rosaado-Seijo: Of course, hanging out is essential for art projects.

In the construction of El Bowl de La Perla (La Perla’s Bowl), we were all a group of friends. I had a skate ramp set up in my studio, as a part of another project titled History on Wheels, and some skater friends from La Perla had a key to come in whenever they wanted. When I had to leave that studio, the boys asked to place the skate ramp in the coastal neighborhood, La Perla, and in the process of relocating it, we thought about making it out of cement, as our friend Boly was always suggesting, using debris from some torn-down houses in the area recently and were perfect for it. That same day, a friend said he could bring his Bobcat and move the chunks of debris for us, and, in the same spirit, neighboring folks started to help— with certain doubts that we would succeed at making a skating bowl in two months, but collaborating anyway from the beginning. I believe it all came to fruition because we had been hanging out in that neighborhood for a long time, for real.

Honestly, El Bowl is the best proof of something made through hanging out. The whole time, we enjoyed the process of making the bowl as a pool/sculpture. We worked every day, hanging out and having a great time. We never went there to suffer or have unpleasant times. If things weren’t going well, we would hop on our skateboards and take off.

Diana: Part of your work is characterized by an active participation from the communities you are involved with. How do you get your collaborators to participate in the aesthetic thinking or metaphorical aspects of a project?

Chemi: Generally, I try to work from the common knowledge we share in Puerto Rico, and part of what has worked in the projects is that they are related to the history of the site and the place.

In a project like El Cerro2, the metaphor emerges thinking like an ordinary citizen; it’s like a game, “to turn The Hill into a hill”, recognizing there are a lot of other implications like neighborhood pride and the place’s identity. After a while, we would be negotiating super swell about aesthetic issues with the community, for example, deciding which house should be painted next, what shade of green to use, or painting the best maroon house, really considering the color palette in detail.

I grew up in the countryside, and here in Puerto Rico there’s the imperialistic idea that the rural is the old, the abandoned, and that the city and modernity are the best. So, within that game of actually turning The Hill into a hill, by using green and maroon, we can question everything from our relationship with nature to whether art can really make a social intervention that works for something, and change the perspective about that nature and rurality that people have wanted to reject.

It is also important that what we do makes sense and has quality. It’s important that my son likes it, as well as my skater friend, and my brother who is an agronomist, and the people I appreciate, who know me and know my work. It is also important to share it with someone like you or Bubu, who has another knowledge of art. It is equally important that my mother and collaborator, a feminist professor and activist social worker, sees it as something beautiful too, as a good metaphor, as a work of art.

Something about Puerto Rico is that, fortunately, we learned to work as a crew with the homies, and we all do it openly all the time. It’s important for us to share our ideas, to ask each other questions. That’s why my ideas can come with Bubu’s input, or from whoever I am hanging out with at the moment, and I share that without fear.

Diana: I became a social worker after I moved to the US and couldn’t find a job in the art field, and I would like to know what kind of possibilities you see between social work and the arts from your experience with your mom?

Chemi: We collaborate a lot. My vision of social work is not that of a worker sitting in an office but one who is really for and in the neighborhood. There are methodologies we have developed together, such as asking questions, getting to know the neighborhood’s history and the needs people tell you about, and then coming up with solutions.

I think that is important, the methodology of social work that asks, learns, and builds relationships, which can also be done through art. If, as artists, we hold ourselves accountable, work at a site, learn its history, and think about what needs to be worked on in this specific place, we will end up doing social interventions with a social work approach.

Diana: How do you approach your projects when working with communities you’ve had no previous relationship with?