Fall 2023

Cover

Letter From the Editors

Something that seems to connect us all as artists is our ability to bring our own personal histories and experiences into our work. This ensures that no two of our practices are the same; each is based on a unique perspectives,

This collection of interviews explores the people, places, and projects that have had an impact on our own practices.

Many of us have found our own families to be sources of knowledge and inspiration, alum and current students alike. Multiple alumni have done projects with their families over the years such as Salty Xi Jie Ng’s ongoing project, Grandparents Residency, which she describes as “Creating a myriad of experiments with grandparents as site, I explore coming-to terms with their mortality.” In the current issue, Gilian Rappaport interviews their aunt about her art practice and Luz Blumenfeld talks to their mom about the parallels between her work in psychoanalysis to their art practice and Olivia DelGandio speaks with her dad to channel her dead grandma.

Several students chose to interview artists they admire in this issue. Clara Harlow talks to artist Ross Carvill about his illustration practice and Adela Cardona interviews Limei Lai, a multidisciplinary artist and curator.

Last fall, we dedicated an entire journal issue to interviews with program alumni and even when that isn’t the case, our relationship with program alumni stays strong. This fall, Nina Vichayapai interviews alum Amanda Leigh Evans about her project, The Living School of Art.

Manfred Parrales chose to speak with another student, Midori Yamanaka about their shared experiences, and she reached out to the founder of an artist residency program in Japan. Our connections reach far and wide.

Each term, each issue of this journal, we get the opportunity to gain insight into our own practices by sharing space and time with others in the interview format. While we see many connections between interview subjects throughout the years, no two are the same. We hope you enjoy the latest issue of the Social Forms of Art Journal.

Sincerely,

Your SoFA Journal Editors: Luz Blumenfeld and Olivia DelGandio

Sapporo – San José via PDX

“[Loneliness] is a crucial aspect of self-discovery and understanding others’ pain. To those experiencing loneliness, it’s okay to feel that way, and remember, you are not alone.”

-Midori Yamanaka

Two years back, I kicked off this artsy journey, saying goodbye to sunny/tropical home San José, Costa Rica, and diving into the weirdness of Portland, OR. Since then, it’s been a mix of experiences, about art and personal discoveries. In the middle of it all, I have been learning that even in intense experiences, you’re never truly alone.

Being in the Art and Social Practice program at Portland State University is not just about art lessons for me. It has been a chance to connect with cool people from all over the world, people I wouldn’t have met otherwise.

Now, I’m excited to share a chat with Midori Yamaka, a Japanese artist and coincidentally, my cohort classmate for this art journey. We’re diving into our shared experiences– from navigating life as artists and immigrants in the United States to unraveling Portland’s weirdness. Our chat touches on loneliness, the powerful impact of socially engaged art, and the quirkiness ethos “Keep Portland Weird” vibe.

This interview isn’t just a chat between a Costa Rican and a Japanese artist; it’s a journey into how Sapporo and San José found a cultural exchange in the heart of Portland, Oregon. Join us as we explore the ties between our diverse backgrounds.

Manfred Parrales: Midori, your artistic journey has taken you from Japan to Los Angeles, and now to Portland. Can you share a bit about the cultural influences that have shaped your artistic identity?

Midori Yamanaka: Hello! Indeed, my life has been a fascinating tapestry of cultural experiences. Growing up in Japan, studying in Los Angeles, and now residing in the eclectic city of Portland, have all played a significant role in shaping my artistic perspective. Each place has contributed a unique hue to the canvas of my creativity.

Manfred: The transition from Japan to the United States must have brought culture shock. Could you share a specific moment that stood out during this transformative period?

Midori: Absolutely. One of the most surprising cultural shocks occurred in the restroom. In Japan, there’s a sense of privacy and discretion in such spaces. The openness in the United States, where people don’t mind the sounds, was a notable departure from the cultural norms I grew up with.

Manfred: Your practice is deeply rooted in social art. For those unfamiliar with social practice, how would you define it? How do you define your approach to art and social practice, particularly within the dynamic context of Portland?

Midori: I define art and social practice as the newest form of contemporary art that engages with ordinary and extraordinary aspects of our society and lives. Living in Portland has been incredibly inspiring for my social art practice. The city’s social awareness, progressive culture, and vibrant communities align seamlessly with my passion for cultural exchanges and education. Discovering the field of Art and Social Practice was a revelation, providing a fitting framework for my endeavors.

Manfred: Portland is known for embracing weirdness. How has this unique aspect of the city influenced your creative process?

Midori: I adore the “Keep Portland Weird” ethos. It encourages creative freedom and self-expression. Portland’s acceptance of individuality resonates with me, fostering an environment where being true to oneself is celebrated rather than stigmatized.

Manfred: Loneliness is a universal experience, especially for international artists or immigrants in general. How did you navigate moments of loneliness, and what advice would you offer to others going through similar emotions?

Midori: Loneliness was a significant part of my early years in the US. Initially, I employed the survival skill of ignoring it, but eventually, I realized the importance of facing and overcoming it. It’s a crucial aspect of self-discovery and understanding others’ pain. To those experiencing loneliness, it’s okay to feel that way, and remember, you are not alone.

Manfred: “Keep Portland Weird” is more than a slogan; it seems like a way of life here in Portland. Can you share a particularly quirky or strange encounter you’ve had in Portland?

Midori: One of the charmingly weird aspects of Portland is its unpredictability. I embrace the uniqueness of the city, where what may seem weird to others is just another thread in the colorful tapestry of Portland life.

Manfred: Let’s delve into these cross-cultural impressions further. When it comes to Japan, the association with order, pristine spaces, and a strong work ethic is vivid. The precision and dedication of Japanese art, like that of Rei Kawakubo, indeed commands great respect to me. There are generalized ideas of what we believe about other countries or cultures, what ideas come to your head when you hear Costa Rica or Latin America in a more general idea?

Midori: Believe it or not, I have had the opportunity to be in Mexico and Brazil. When I think of Latin America, I think of happy people, dancing, eating, and having friends over. It’s a very positive image.

Manfred: Looking ahead, what do you envision for the future of your art practice, and what challenges do you foresee?

Midori: The future is an open canvas for me. I am currently happy with the opportunities Portland has provided, and while uncertainties exist, I’m open to change and excited about potential opportunities. The world is changing rapidly, and I look forward to embracing the shifts and evolving with them.

Midori Yamanaka (she/her) is a Socially Engaged Designer. Midori has been exploring who she is and how to make herself and the world better. Midori thinks that It would be great if you can come across and work together. She is excited to hear your stories and your dreams. She would be very happy to help you with your challenges and share what she has. She thinks that together, we can make our world better.

Manfred Parrales (he/him) is an artist with a passion for design, art history, and social practice. Born in San Jan Jose, Costa Rica he is pursuing MFA studies in Art and Social Practice at Portland State University.

He is a passionate art enthusiast, driven by the desire to communicate and educate through the language of art. His artistic journey involves crafting innovative solutions for art communication, immersive experiences, and multicultural dialogues. Utilizing the tools of video, photography, and art history, he shapes conversations around art as potent social instruments. His expertise extends to contributions to education and cultural institutions across the United States and Latin America. For him, the core of art lies in the ability to communicate through and by art.

The Magic of Neighborliness

“Knowledge is held in communities and in our bodies.”

-Amanda Leigh Evans

My dad has worked as a mechanic for over forty years. Growing up, it was a common sight to look out the window to see him laboring with precision and care over our many aged but well-loved and maintained cars. In addition to being a mechanic, he oil paints, cooks Thai food, and helps my mom run our family restaurant.

So when Amanda Leigh Evans said, “Knowledge is held in communities and in our bodies,” I immediately understood what she meant. Amanda was shaped by her own roots from a working class family when she set out to create a program during a five year artist residency at an East Portland apartment complex. Interested in tapping into the vast knowledge that her neighbors there possessed, Amanda started The Living School of Art to connect neighbors in the sharing of their skills with one another. There, acts of neighborliness led the way for creating community gardens, laundry room art galleries, programs for kids and adults, and so much more. In my search for models of education happening outside of traditional academia, models which recognize the knowledge held by people like my dad, I am drawn to Amanda’s work. I spoke with her to understand the myriad of influences and support that went into The Living School of Art.

Nina Vichayapai: Could you start with an overview of what The Living School of Art was?

Amanda Leigh Evans: The Living School of Art came out of this five year artist residency that I was offered in an affordable housing apartment community in East Portland. When I was in the PSU Art and Social Practice program, I had a friend who worked at Zenger Farm, which is a nonprofit community farm in East Portland. That friend, Krysta Williams, ran a teaching chef program for women who are immigrants and chefs. The women would use produce from the farm to teach workshops on recipes that they were experts on. It was a really beautiful multilingual experience. In 2015, Krysta and I wrote an application for a Precipice Fund grant through PICA (Portland Institute of Contemporary Art) to work with some of the women from the chef program to develop a series of meal-artworks about building connection across age and language and culture.

In that project, called The Global Table, Krysta and I worked with three chef collaborators. Farida from North Africa, Blanca from El Salvador, and Paula from Oaxaca in Mexico. The five of us collectively designed a series of meals over the course of several months. Each of us invited our family and friends and asked that they commit to multiple meals together. We grew as a community by sharing these meals together. The group was an intimate group of around 20 participants, which ranged from children to elders

Our very last meal was a public event during the Art and Social Practice’s annual art conference called Assembly. Lots of people came to that event who hadn’t come to the more intimate dinners. A woman named Jessica Preboski was in town for Assembly and she attended the event. She was part of a nonprofit in Southern California called Community Engagement, which worked with affordable housing communities to develop artists residency programs in Santa Ana, CA and Phoenix, AZ. I was familiar with this residency program because I had a friend who was an artist in residence at an affordable housing community in Santa Ana. I often thought about that residency program while going through my MFA and wanted to apply to it when I finished my degree. When I was young, like in middle school and high school, I dreamt of creating an art school in my community and involving my neighbors in that process. This dream is what led me to eventually become an artist.

Nina: What a serendipitous encounter. What came out of that meeting?

Amanda: Jessica came to our last dinner at Zenger Farm. She had been working with an affordable housing community in East Portland that wanted an artist residency. Zenger Farm is very close to the apartment complex where I ended up being an artist in residence. Neighbors at this apartment complex really liked gardening, food, and cooking. They were also very interested in engaging crafts-based practices, which is part of my background since I work in ceramics. After the meal, Jessica asked me to apply to be an artist in residence at the apartment complex.

Nina: What was your initial reaction to the opportunity?

Amanda: I was really excited about the possibility, but I also felt conflicted. While I do share some similar backgrounds to many of the neighbors in the apartment complex because I grew up in a diverse working class community, I am not an immigrant. And many of the neighbors in the apartment complex are immigrants or refugees. The apartment complex is composed of families primarily from Nepal, Somalia, Afghanistan, Guatemala, Mexico, Ukraine, Russia, Romania, Bosnia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and more. Additionally, there are many single, older white people who have disabilities living in the complex. What is shared among all neighbors is an income-level under which they had to qualify in order to be granted access to this affordable housing.

When Jessica invited me to apply, I thought, “Am I the right person for this work with my lack of ability to relate to those experiences?” So I originally responded to Jessica with a list of other artists that I felt could be a better great fit. And then a few months later, Jessica came back to me and she was like, “We really want you specifically to apply, will you apply?” And so I did, and the five subsequent years I spent developing The Living School of Art were some of the most beautiful and fulfilling years of my life.

When I applied to Community Engagement’s artist residency, the framework was quite loose. I was provided housing, a stipend, and a small budget for supplies. Originally, they asked me to be an artist in residence and to live and work in the apartment complex for one year, but I ended up being an artist in residence for five years total. It was very open ended. At the beginning, I asked my neighbors, “What do you want to do with this opportunity? We have a space that we can use as an art studio, we have some funding for supplies, and we have time together.” The structure for The Living School of Art emerged from the responses that the neighbors gave.

Nina: That’s fascinating. And it sounds like such a serendipitous encounter that evolved from the seed that was planted in you way prior to that meeting. I’d love to know more about what your influences were in deciding how to structure the school.

Amanda: It was definitely a combination of influences. As an undergrad, I studied sociology and community development, as well as art. I became interested in forms like Participatory Action Research and community-initiated practices. I’m also really interested in artists like Rick Lowe, who has been committed to Project Row Houses for nearly 30 years now. Rick Lowe has worked in a row house community in the third ward in Houston on artist-driven projects for many years. It’s also a collaboration with single mothers. Some of the houses are devoted to artist residencies and exhibition spaces. I admire his commitment to one place and one community for such a long time.

I’m also inspired by artists like Mierle Laderman Ukeles for that reason, because she has been committed to a specific practice and community for decades. I really admire that commitment and am interested in what happens in the slow unfolding of a relationship over decades.

However, I would say the artist who has had the biggest impact on me is Theaster Gates. For one, I can relate to his background as an urban planner through my study of sociology. I like the way that he thinks about systems like housing and architectural spaces, including affordable housing. Additionally, Theaster Gates is also a craftsperson, specifically a ceramic artist, who values beautifully-made objects. The way that he thinks about ceramics and its history and potential for social connection has also been very inspiring to me. Lastly, Theaster Gates’ dad was a roofer. I also share that blue collar background. My dad has worked in construction since he was 16 years old, and he’s still working in it today at the age of 70. The way that Gates creates works that draw from his working class roots, from his dad’s craft-adjacent manual labor job, is something that I particularly identify with.

Beyond that, I’ve also been interested in various alternative art schools and artist collectives. All of those interests swirling around led to how I developed an approach to co-creating The Living School of Art, which began with a curiosity on what knowledge was held in our community. What topics were neighbors already experts on? What do people know well that they haven’t shared with other neighbors? How can we create a system that celebrates the knowledge held by our community that allows for people to share across age, language and culture? And what community interests haven’t been explored yet? What collaborative framework can we create that allows for intuitive creative exploration?

In addition, at this apartment complex, for over a decade a woman named Tia Bennett-Tveisme has run a very successful after school program and series of annual community events. So there was a foundation that I walked into because of her work. The Living School of Art was built on the foundation of Tia’s work (by the way, this Tia is not to be confused with Tia Kramer, who is now my collaborator in Walla Walla, WA and an alum of the PSU Art and Social Practice Program).

At many apartment complexes, the annual turnover rate in rentals is quite high, but in this particular complex, there are many families who have lived there for a decade or longer. Unfortunately, some of this changed during the pandemic, but this was true when I arrived. Anyway, what that meant was there were lots of kids who grew up together, who ride the bus every day together, who go to school together, and parents who watch each other’s kids on this playground that exists in the center of the complex. I came in with all these social structures already in place, but there wasn’t a forum for neighbors to share their knowledge or to be creative.

Nina: That’s amazing. To have those structures already be part of the community and the way that they are connecting with each other and the importance of building those connections over a long time. What was it like working with your neighbors? And what kinds of things did people teach each other?

Amanda: During the first year of my artist residency, The Living School of Art didn’t have a name. The name emerged around the one-year mark of the project as a way to define what we had organically started to do. Initially, working with the kids was an easy entry point into the community because they were so eager to make art.

One of the biggest resources that we had in the apartment complex was time. In some ways, it felt like we had infinite time because it was time at home. In the summer, the kids were around all day every day. And for adults, anytime someone wasn’t at work or at school, we had some time to do things together. Because the kids were around a lot, that led to a lot of initial experimentation and spur-of-the-moment activities.

Our first major project was a community garden built in a former swimming pool in the middle of the complex. The pool was bean-shaped and all of the cedar wood raised bed garden boxes were built to fit the contours of the pool. The garden is a really charming, unusual space. I think of it like earthwork. It really feels like a living artwork.

We also built a beautiful greenhouse out of recycled windows covered in paintings by the kids, which neighbors use annually to sprout seeds. Every spring, it’s filled to the brim with young tomato plants, which seem to be a favorite among neighbors. There’s this charming handmade quality to that garden space that exists in stark contrast to the banal, standard-issue apartment architecture surrounding it.

In addition to children and garden programs, there was also a weekly women’s program. Each week, while the kids were at school, a different mom would lead that group and teach something based on her creative practice. A lot of amazing cooking happened in that group and sharing of recipes. One week we did eyebrow threading, another week someone led a performance art activity that expressed the daily stresses and fears of deportation. Because the community was so diverse, that all led to a really great exchange in terms of food and craft-based practices and gardening practices from around the world.

Beyond that, there were many impromptu special events. We took a camping trip once. Several times we went kayaking. We’d go to art museums and artist studios. We were invited by the Portland Children’s Museum, Third Space Gallery and National to have exhibitions, which we planned and installed collectively.

We also had eight laundry rooms in the apartment complex. Each of those laundry rooms became a rotating exhibition space. This was work made by neighbors and rotated on a quarterly or annual basis. Much of that art remains in those spaces now. Our work also led to a short-term artist residency program that was funded by a Metro Creative Placemaking grant. We put out an open call for artists who had lived experience in affordable housing or lived experiences as immigrants or children of immigrants. Some of the application questions were written by youth. Two application questions were, “What is your favorite flavor of popsicle?” and “How do you define a rainbow?” Once applications were submitted, youth in the apartment complex reviewed the applications and voted for who they wanted to invite to be an artist in residence with us. Those artists then made public, permanent artwork in collaboration with the young people at the apartment complex, which still remains there to this day.

Most importantly, The Living School of Art was successful because it was built from a serious and intentional commitment to the role of “neighbor,” as an active, accountable, and public role in community. Most people in cities have neighbors, but often a neighbor is just someone who lives near you. There is no commitment or social contract among neighbors in the United States. Within this work, I was very serious about my role as a neighbor. To me, being a neighbor is an active commitment to a place and a community. Being a neighbor is a civic responsibility. The Living School of Art was possible because of a shared commitment to being neighbors. I lived in the apartment complex and I lived actively as a neighbor. Neighborly interactions were the glue that held everything together. There was lots of sharing of tea and coffee in living rooms, driving people to doctor’s appointments, helping someone file for unemployment, little gifts from the garden left on doorsteps, evening chats in the garden, random babysitting, teaching someone how to drive, helping someone move a couch, and so on. My life, my home and my work were deeply intertwined and I felt like, for better or worse, but mostly for better, I was deeply known, and with that knowing comes responsibility. And my neighbors also showed up for me in similar ways. This neighborliness was necessary in order to build the magic that emerged during making art together.

Nina: So, how has The Living School of Art shaped your ideas about education?

Amanda: I mentioned earlier that I grew up in a working class family. I was in the first generation of people in my family to go to college. My dad works in construction and my mom worked at a beauty salon. Both of those practices require attention to craft and aesthetics, and I learned these critical artistic skills from my parents. I didn’t go to an art museum until I was in college, yet I had decided to study art. Art museums weren’t places that were familiar to me when I was a young person. I came to art through domestic art practices and through art classes in public schools.

I am very interested in how class dynamics affect access and belonging in the field of visual art. Many neighbors at The Living School of Art have similar vocations to those of my parents. They work in healthcare, construction, food service, etc. Those jobs can be very creative! What scrappiness, creative problem solving, and ingenuity can emerge when people with those skills come together to make artistic projects? Often, that artwork is so much more interesting to me than work made by artists who have received abundant financial support and artistic training since birth. When I enter conventional art spaces, I often wonder “Who is this art space for? Who is its assumed public? Who feels a sense of belonging in this space? How does this affect our perception of value and cultural capital?”

In The Living School of Art, we made art with and for ourselves. Our community defined what artwork and art practices were important to us. What could art mean if we were defining it for ourselves? Knowledge is held in communities and in our bodies.

At the same time, I now have a master’s degree. I am formally trained in visual art and I am no longer working class. Using and sharing specialized training is a public responsibility to me. At some point, I realized my neighbors expected me to share my training as an artist, especially if I was asking other people to share their knowledge. At the beginning, I was diminishing this training and wasn’t sharing it. Then at some point I realized this is why I went through school. Like, if you’re on an airplane and someone’s having a medical emergency, you would expect any random passengers with medical expertise to use their training in that situation. My neighbors expected me to share my art knowledge.

By defining The Living School of Art as an alternative art school or as an artist collective, we were using both of those terms; our framework allowed for any neighbor to be an expert and to be a teacher. This led to anywhere from five year olds teaching classes to women who were retired teaching classes on things within their realm of expertise that you might not learn in a conventional art class.

Art in the twenty-first century is driven by conceptual frameworks rather than materials or techniques. Any type of practice can become a contemporary art practice. The Living School of Art is an artwork in and of itself, which created a framework for art practices to emerge. I think about John Dewey’s Art as Experience, but perhaps more importantly I think about craftspeople working together in communities in collaboration with each other for millenia. Some of the oldest ceramic objects are Jōmon pots from Japan, and it’s believed that those pots were made by communities of women. And so, the structure of The Living School of Art is radical because it pushes against contemporary educational structures, but it is also based on ancient frameworks because it draws from craft structures that have existed for over twenty-thousand years.

Nina: It seems like a lot of your work has involved being a facilitator through connecting people to the knowledge of those around you. I’m also curious since you practice ceramics, how did that fit into The Living School of Art? Or into your ideas in social practice overall which tends to be dematerialized?

Amanda: Yes, ceramics have influenced how I think. Historically, ceramic work, unlike painting, has been made in the community. Until recently, there has been no cost-effective way to make ceramic work alone, isolated in a studio. Ceramic artists share kilns and studio spaces, and more importantly, share embodied knowledge.

I have two small kilns and a wheel that I’ve purchased used over the years. We had those resources at The Living School of Art. My apartment was next door to a shared studio space where we would hold classes and gatherings and also just have open studio time. There were several neighbors who had keys– like teens who would come in and just use the space and other folks. Especially during the pandemic lockdown, ceramics were important because it was something really special that I could share that neighbors typically wouldn’t have access to.

If you’ve never had exposure to art making and you’re making it for this perceived general audience (as we sometimes did for exhibitions at off-site locations), I think it’s critically important to also have art in your home and to be living with it.

I think socially engaged art can be a really powerful way to approach artmaking because it expands perceived audiences and methods of collaboration. But I think social practice is assumed to be very dematerialized. However, the way that I approach social practice is in relationship to objects, contexts, and experiences. There have been plenty of valid critiques from socially engaged artists about the shortcomings of static, commercial art objects in a gallery. But that doesn’t mean that art objects are inherently evil, wrong, or dead. Social practice doesn’t have to be anti-object. I fell in love with art because I like to work with my hands; I like to build things with wood and with clay, and I work in design practices too. I love making things and I love eating from ceramic objects made by people who are important to me. And the joy of creating is something that I want to share with people. Creating beautiful objects for domestic spaces can be considered elite, but it is also a working class practice and I think everyone deserves to have access to that.

Nina: That’s amazing to hear as someone who makes objects and is trying to figure out what social practice looks like for me. I’ve felt a sense of needing to put object making on hold for social practice but so much of my joy comes from making and sharing art with others just like you described. You articulated beautifully what it can mean to make an object in a socially engaged way. Do you have any advice for anyone who wants to provide educational opportunities to people or youth outside of academia or traditional institutions?

Amanda: I think about Sister Corita Kent’s 10 Rules, which include, “Find a place you trust and try trusting it for a while.” What communities are you already part of? Who can you partner with? Who has been doing similar work?

All of the work that I’ve had the chance to do over my career has been in collaboration with other people who are also doing that work. There’s nothing that I’ve built from total scratch. Find the people who share your values and interests, and create something together.

Nina Vichayapai (she/her) uses fabric as a language to reveal how surroundings embody humankind. Her work explores physical spaces as expressions of the many people who shape them. Through hand stitched textiles she addresses the important role of homemaking in establishing belonging within the American landscape.

Born in Bangkok, Thailand, she graduated from the California College of the Arts with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 2017. Nina currently lives in the Pacific Northwest.

Amanda Leigh Evans (she/her) is an artist, educator and cultivator investigating social and ecological interdependence. Her work manifests as ceramic objects, gardens, books, websites, videos, sculptures, and long-term collaborative systems. Her work is rooted in design thinking, research-based inquiry, and long term collaboration, often resulting in artwork that exists outside of traditional gallery spaces. For five years (2016-21), Evans was an artist-in-residence in an affordable housing complex in East Portland, where she collaborated with her neighbors to create The Living School of Art, an intergenerational alternative art school that centered the creative practices of their multilingual community. Before that, she was a collaborator with the LA Urban Rangers (2011-13) and Play the LA River (2013-15) on projects engaging the history, politics and ecology of the LA River. Currently, Evans is a Visiting Assistant Professor teaching ceramics and socially engaged art at Whitman College in Walla Walla, WA. She and her collaborator Tia Kramer are the DeepTime Collective, an artist collective developing When The River Becomes a Cloud (2022-25), a co-authored contemporary public artwork generated through a long-term artist residency at a Pre K-12th grade public school in rural Eastern Washington. Evans holds an MFA in Art and Social Practice from Portland State University and a Post-Bacc in Ceramics from Cal State Long Beach.

Life of Art and Artists

“It’s art. I’ve come to realize it’s not just the creations of artists, but also the remnants left by those around them. That is when I realized the importance of archives.“

– Hisashi Shibata

(これがアートなんだぁ…と。作品とは、アーティストだけでなく、周囲の人が残したものでもあるのだ、と。その時、本当の意味でアーカイブの大切さがわかったんです。-柴田尚)

NPO S-AIRは、1999年より札幌でアーティストインレジデンスを行っています。私がアートアンドソーシャルプラクティスの道を歩むきっかけのひとつが、このS-AIRでした。

Since 1999, S-AIR has been running artist-in-residence programs in Sapporo, Japan. S-AIR was one of the reasons I decided to pursue the path of art and social practice.

私は以前、S-AIRが主催するイベント「AIR CAMP」で、ベトナム、カンボジア、そしてフィリピンからの招聘アーティストのプレゼンテーションとアーティストトークの通訳を担当させてもらいました。そこは国際交流の場であり、発見と学びの場でした。私のとっては、さまざまなアーティストのあり方が存在することを知った場所でもあります。

At an event called “AIR CAMP,” hosted by S-AIR, I was in charge of interpreting presentations and artist talks by invited artists from Vietnam, Cambodia, and the Philippines. It was a place of international cultural exchange, discovery and learning. For me, it was also the place where I learned that there are many different ways of being an artist.

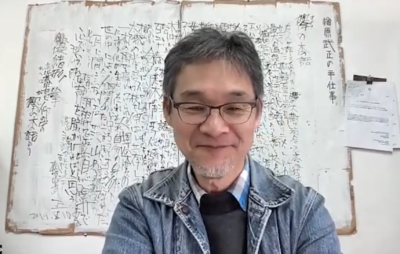

今回は、S-AIRの創設者で代表の柴田尚氏に、アートを職業にすること、そしてアーティストインレジデンスについて伺いました。

For this article, I interviewed Nao Shibata, the founder and representative of S-AIR, about being a professional in art and artist residencies.

Midori Yamanaka: アーティストを職業と考えると、他のフィールドよりもさまざまな挑戦が多いように思います。柴田さんご自身はどのようにアートを仕事にされて来たんですか。

When you consider being an artist as a profession, I think there are more challenges than in other fields. Mr. Shibata, how did you get into art as a career?

Hisashi Shibata: 僕自身、仕事って何なのかというのを、ずっと考えています。

I’ve been thinking about what work is all about.

中1の時に、父親が癌になりました。父は、中学校しか出てないペンキ塗装工のペンキ屋でした。母親は、文字を見るのも嫌い。両親とも学のない家庭に生まれ育ちました。で、大黒柱の親父が癌になったんで、もう高校進学も諦めて、すぐ就職してくれという感じでした。ブルーカラーの土地柄だったので、それも普通でした。

My father got cancer when I was in 6th grade. My father was a painter who only attended junior high school. My mother doesn’t even like looking at letters. I was born and raised in a family where both my parents were not highly educated. Then, my father got cancer, so my family told me to give up on going to high school and get a job right away. I came from a blue-collar area, so that was normal.

そこから、芸術の大学の先生になるってのは、もうものすごいウルトラCなんですよ。

Coming from such a situation, becoming a professor at an art university is already a huge career advancement.

Midori: 本当ですね…

I can see that.

Hisashi: そんな状況だったので、美術大学を志すところから、もう大げんかでした。「お前は何をしようとしてるのか」と。親の貯金通帳を叩きつけられて、「これだよ?どうやって生きていくの?」と言われました。

Because of that situation, I had a big fight about wanting to go to art school. My parents said, “I don’t understand what you are trying to do,” while their bank statement was slapped on me. They asked “This is what we have. How are we going to survive?”

それで僕は、二浪までしたんですよ。

So I spent a good two years before going on to higher education.

Midori: すごいガッツ!

How determined you were!

Hisashi: 何度も諦めそうになったけれど、何故か学校の先生が説得しに来たり、親戚が親を説得しに来たり助けが入った。

I almost gave up many times, but for some reason my school teacher came to persuade me, and my relatives came to persuade my parents, and I got help.

浪人した時は、自衛隊入隊の手続きもしたし、職業訓練校の手続きもしました。でも、そんな境遇からたまたま逆転してこうなってる。

Before getting into university , I also went through the procedures to join the Self-Defense Forces and to attend a vocational training school. However, this situation happened to turn around and turn out like this.

Midori: すごい!

Wow.

Hisashi: そんなわけで、僕自身はもう大学の時まで50種類ぐらい仕事をしていたんです。(浪人中の)予備校代とかも自分で稼いで行っていたし。

That’s why I had already worked about 50 different jobs until I was in college. I also paid for my own prep school fees.

そして、いつもお金のことがついて回っていた。お金って何なんだろうってのをずっと考えながら今に至るんです。

And I always had to worry about money. I’ve been thinking about what money really is until now.

そう考えて見ていると、学生も同じです。

If you think about it that way, students are the same way.

みんな好きなものがあるけれど、どうやって生きていくんだっていうところを探している。だから僕もよく話すんです、仕事って何なんだろうねって。

Everyone has something they like, but they’re all looking for ways to make a living. That’s why I often talk about what work is all about.

お金を稼ぐものってそれも大事なんだけど、環境が違うと状況が全然違いますよね。例えば、アートで食う人なんて、欧米に行くといくらでもいるわけですね。

Making money is important, but the situation is completely different depending on the environment. For example, if you go to Europe or America, there are many people who make a living through art.

アートを仕事にしてると言っても、色々ある。アートを仕事にしているというだけでは、ぜんぜんうかばれない社会もある。そこに悩んでる人たちもいっぱい見た。国によっては生活保護みたいな感じで、アートやってるってだけで助成金が出るとか…

However, even if you say that you do art as a job, there are many different things. In some societies, just because you do art as a job, you are not respected at all. I saw a lot of people suffering from this problem. In some countries, artists can receive grants or subsidies just for doing art, similar to social welfare benefits…

Midori: そうですね。

Yes.

With participants of AIR CAMP held in Sapporo in 2015. Participants range from local citizens who love art to artists from other regions and people involved in the art industry, all of whom come together to learn while interacting with the invited artists.

© S-AIR

Hisashi: だからもちろん、食わなきゃいけないんだけど、食うっていうことが仕事じゃないんじゃないかなって思っています。

So, of course, I have to make a living, but I don’t think work is about paying the bills.

一生のうちにやらなければいけないこと。何かそういうミッションみたいなことがあったら、バランス取ってやってほしいなって。

It’s something you must do in your lifetime. If there’s a mission like that, I want them to find a way to do it.

Midori: いわゆるライフワークってやつですね。生活のためにではなく、人生をかけて取り組む仕事…

It’s what you might call a life’s work. Work that you do not just for a living, but for your life…

Hisashi: ミッションみたいなものが感じられるとしたら、それが仕事だと僕は思っています。

逆にいえば、それができなければ仕事したっていうことにならない、と。

If something feels like a mission, I think that’s work.

On the other hand, if I can’t do that, I don’t think I’ve done any work.

Midori: なるほど。

I see.

Hisashi: それをする為に新聞配達しようが、バイトしようが、掛け持ちで色んなことしようが構わないと思います。例えば、社会や環境が違えばアートでお金の得やすいところも、逆に難しいところもある。場所や状況によって大きく異なります。

アート自体を許さない国だってあるわけです。

In order to do that, I don’t care if I deliver newspapers, work part-time, or do a variety of other things. For example, in different societies and environments, there are some places where it is easy to earn money through art, and some places where it is difficult. It varies greatly depending on location and situation.

There are even countries that do not tolerate art itself.

Midori: ありますね。

Yes, there are.

レジデンス自体のそのインパクトについてもせっかくなのでお伺いしたいのです。柴田さんが今まで運営してきた、レジデンスでの一番の効果というか、面白さはどういうところでしたか。

I would like to take this opportunity to ask you about the impact of the artist residencies. What is the most impactful or interesting aspect of the residencies that you have run so far?

Hisashi: うちは、完全なインディペンデントで長くやっています。そういうところは、日本ではとても珍しい。それで、いつもお金がないから、みんな副業を持ってやってくれっていう感じでやってたんです。

それで僕はたまたまその流れで大学の先生にまでなってしまった。それも副業みたいな感じです。

I have been completely independent for a long time. Places like that are very rare in Japan. So, since we didn’t have any money, we all asked people to get side jobs.

By chance, I ended up becoming a university teacher through that process. It also feels like a side job.

Midori: どっちが副業なんですか。大学が副業になったんですか。

Which is your side job? Has university become a side job for you?

Hisashi: 大学も、アートインレジデンスを続けるためにやったんです。ここ(AIR)をやってていいという条件だったので、受けた。国立大学だと、副業禁止みたいに言われることも無きにしもあらずですが、NPO(を運営している実践者として)の立場で大学に迎えたいということで。

I also did this at university to continue my art-in-residence program. The condition was that I could work here at S-AIR, so I accepted. At national universities, it is natural for people to say that they are not allowed to do side jobs, but they would like to welcome me to the university from the perspective of a non-profit organization (as someone who runs one).

Midori: なるほど。

I see.

Hisashi: 面白いですよね。本当にスペシャルだと思います。

It’s interesting, isn’t it? I think it’s really special.

Midori: 大学側としても、いわゆる典型的なルートで来た大学の教授ばかりよりも、民間とかNPOとか、そういう実績を持っている先生に入ってほしかったっていうことですね。

On the university side, it would have been better to have professors with a track record in the private sector or NPOs, rather than just university professors who came through the typical route.

Hisashi: そう。実学者が欲しかったってことです。現場の人間が欲しかった。学者だけじゃなくて。

その流れで、たまたま(大学に)入ったんです。ものすごく珍しいと思います。僕は有名大学出身でもないし、留学もしてないし。

Yes. They wanted a practical scholar. They wanted someone from the field. Not just academics.

I happened to start working at university that way. It’s extremely unusual for someone like me who didn’t go to a famous university, who has never been to study abroad, to get the position.

Midori: 長年アートインレジデンスを運営してきて、やりがいや印象深い出来事はどんなことですか。

Over the years of running the art-in-residence, what has been rewarding or memorable?

Hisashi: 2000年に招聘した、ドミトリー・プリゴフというロシアの作家がいます。当時、彼はもう60歳でした。彼は、ペレストロイカまで弾圧されていました。

There is a Russian writer named Dmitry Prigov, whom we invited in 2000. At that time, he was already 60 years old. He was repressed to the point of Perestroika.

彼の札幌滞在中、彼は日本の大学5〜6校の文学部から招待を受けました。

During his stay in Sapporo, he received invitations from the literature departments of five or six Japanese universities.

Midori: 大忙しですね…!

Oh..wow. So busy!

Hisashi: 札幌でアートインレジデンスに招聘したのに、東京でNHKのロシア語講座にまで出てた。

We invited him to Art in Residence in Sapporo, but he even appeared in aRussian language program on NHK (Japanese Public BroadCaster) from Tokyo.

Midori: 何だか、出稼ぎに来たみたい…

It seems like he came here to work…

Hisashi: うん。だけどね。本当にお金に困ってたみたい。

Yeah. But, it seemed like he and his family in Russia were really in need of financial support.

Mr. Dmitry Prigov (right) and Mr. Shibata sitting next to him during Prigov’s stay in Sapporo in 2000. © S-AIR

(生活費として)6万円しかあげてなかったのに、ほとんど食うや食わずやで、残りのお金を持って帰ろうとしてました。

Even though we had only given him 60,000 yen (about $405 USD) for meals, he was barely able to eat and was trying to take the rest of the money home with him.

でも、その作家、実は(ロシアに)帰ってから、毎日テレビに出るくらい有名になった。(私たちが招聘してから)10年後くらいに亡くなった時には、エルミタージュ美術館で大回顧展も行われました。

However, since the writer returned (to Russia), he has become so famous that he appears on TV every day. He passed away about 10 years later (after we invited him), and a major retrospective exhibition was held at the Hermitage Museum.

それで、日本でも展覧会ができないかって、いろんな人がうちに調査に来ました。それまでは誰一人、何も言ってこなかったのに。

So, many people came to us to investigate whether it would be possible to hold an exhibition in Japan as well. Until then, no one had said anything.

驚きました。死んだ後に、プロフィール伸びるんだぁって。ゴッホの時代じゃないのに、って。

I was surprised. His profile was growing after he died, even though it’s not Van Gogh’s time.

Midori: たしかに。

I see.

Hisashi: さらにそこから10年経って、ドキュメンタにも彼の作品がでました。

Ten years later, his work also appeared in Documenta, Germany.

Midori: 今の時代でもそんなこと本当にあるんですね。

Wow..it happens even nowadays…

Hisashi: これがアートなんだぁ…と。作品とは、アーティストだけでなく、周囲の人が残したものでもあるのだ、と。

It’s art. I’ve come to realize it’s not just the creations of artists, but also the remnants left by those around them.

作家の寿命よりも、作品の寿命の方が長いんですよ。これは、衝撃的でした。

The lifespan of a work is longer than the one of an artist. This was shocking.

うち(S-AIR)はどこまで見ていくんだろうって。どこまで責任…責任はないけれど、死んだ後もいろいろなことがあります。続きます。

I wonder how far we, as S-AIR, an organizer of art-in-residence will go with artists. How much responsibility we have…I mean we don’t really have much responsibility, but there are many things that come after artists die.

その時、本当の意味でアーカイブの大切さがわかったんですよ。

That is when I realized the importance of archives.

Midori: 今、まさに私たちが学んでいるアートアンドソーシャルプラクティスは、アーカイブが大切な要素のひとつです。特に私たちが今やってるものっていうのは、最終的な作品が目的ではなくて、そのプロセスであったり、そこでの関わりであったり、インパクトっていうことを狙いにしているので、やっぱりどこで切り取るかによって全然違うんですよね。

今のは、私たちのアーカイブへのモチベーションを上げてくれるお話でした。ありがとうございました。

Archives are one of the important elements of the art and social practice field that we are learning. In particular, art and social practice is not aimed at the final product, but rather at the process, the involvement, and the impact. Archives are also completely different depending on how they are conducted and where you see the project from.

So your story was one that motivated us to archive. Thank you so much.

山中 緑(やまなか みどり)日本生まれ、日本育ちのソーシャルプラクティスアーティストで教育者。現在は、オレゴン州ポートランドをベースに活動中。アートとしての国際交流やコミュニティでの協働における創造性の拡大を模索。多様な社会における学び合い、育ち合いを探求している。代表作には、日本の書道をベースに相互のインタラクションを生む“What is your name?”、コーチングメソッドを活用し、会話を記録した”Art of Conversation”などがある。アート センター カレッジ オブ デザインでグラフィック デザインの学士号を取得。現在はポートランド州立大学大学院にて、アートアンドソーシャルプラクティスを実践・研究。

https://www.midoriyamanaka.com/

Midori Yamanaka (she/her) is a social practice artist and educator born and raised in Japan, currently living and working in Portland, Oregon. Her practice explores expanding creativity in international exchange and community based collaboration. She explores mutual learning and mutual growth in a diverse society. Her representative works include “What is your name?,” which creates mutual interaction based on Japanese calligraphy, and “Art of conversation,” which records conversations using coaching methods. She holds a BFA in Graphic Design from Art Center College of Design, and currently is studying and practicing Art and Social Practice at Portland State University. https://www.midoriyamanaka.com

柴田 尚(しばた ひさし) 特定非営利活動法人S-AIR代表、北海道教育大学岩見沢校教授。1999年、札幌アーティスト・イン・レジデンスを立ち上げ、2005年7月、特定非営利活動法人S-AIRとして法人化。初代代表となる。同団体は、2008年の国際交流基金地球市民賞を受賞。海外からの招聘アーティストは100名を超え、日本から海外へも20組以上のアーティストを派遣している。また、「SNOWSCAPE MOERE」など、様々な文化事業を企画している。2009年より北海道教育大学において「廃校アートセンター調査」を開始。専門分野はアートマネジメント、廃校の芸術文化活用、そして アーティスト・イン・レジデンス。2017年、北海道文化奨励賞受賞。

https://s-air.org/

Hisashi Shibata (he/him) is a founder and representative of S-AIR, a non-profit organization, and professor at Hokkaido University of Education, Iwamizawa. In 1999, he launched Sapporo Artist in Residence, and in July 2005, it was incorporated as a non-profit organization, S-AIR. Becomes the first representative. The organization received the Japan Foundation Global Citizen Award in 2008. Over 100 artists have been invited from overseas, and over 20 groups of artists have been dispatched from Japan to overseas countries. They also plan various cultural projects such as “SNOWSCAPE MOERE”. In 2009, he began the “Research on Abandoned School Building for Artistic use” at Hokkaido University of Education. His areas of expertise include art management, artistic and cultural utilization of closed schools, and artist-in-residence.

A Million Ways To Color A Tree

“Art is the one connecting factor. That’s what brought us all together and made us friends. You think it’s just a small drawing in a notebook, but it has a giant power.”

-Ross Carvill

The first time I met Ross, he was wearing a monochromatic green outfit he had sourced from various stoop sales around his neighborhood of Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn that very day. From that moment I knew we would be friends.

Ross is an illustrator from Ireland who uses drawing as a means to connect with people and places around him. Some days this looks like drawing on the windows of a fish market, sketching every dog he pets in a given day, or sheepishly attending a wooden spoon carving club with a whittled leopard bird he made.

Clara Harlow: I’m curious what play looks like to you?

Ross Carvill: Not taking the world for the easiest perception of it. Like, you can easily look at the world and accept it for what it looks like – a tree has branches, leaves are green, dogs only have four legs. That’s easy to do, but if you widen your perception of things a tree doesn’t have to be brown, and it isn’t necessarily brown.

Clara Harlow: I love that too because it speaks to actually looking, rather than just drawing the image of a tree that you have in your head and reproducing that over and over again. You actually have to look at what’s in front of you and ask questions.

Ross Carvill: There are a million ways you can color a tree. But I feel like it’s also about breaking rules, too. People keep telling me “I can’t draw hands,” or “I can’t do perspective.” I want to make a tee shirt that says “Fuck Perspective,” because I feel like people are always getting so caught up in that. Why are we following these rules that someone made like 1000 years ago? People have drawn buildings with perfect perspective hundreds of times. But if you draw a building how you see it, that’s more beautiful in my books than just trying to recreate something that someone else has written for you. Those rules aren’t your rules. Your view of the world is unique to you, so why would you try and censor that by following rules that were written by somebody else? So playing to me means being honest with yourself and your perceptions, I suppose.

Clara Harlow: I feel like the way that you approach drawing is like conversation. It’s your way of speaking and connecting with folks.

Ross Carvill: Definitely, and I struggle sometimes to speak, about emotions for example. But I feel like I digest a lot of stuff through drawing. It’s always like a safe place that I can go to no matter how I’m feeling. If I’m ever trying to explain something, it’s always easier just to draw it and show the person. But it also comes up when I’m asked about what sort of drawings I make. I’ve never been able to answer that question, I always just have to open my notebook and show them. It’s funny.

Clara Harlow: I think that keeps your work really accessible, though. Your style and point of view allows for all sorts of folks to be able to connect with you – about your day, about New York, about funny or hard life experiences. To me, your drawings really function as an invitation.

Ross Carvill: Totally. Last week, I was doing Halloween windows for businesses and people were looking at me drawing through the glass and were really interested in what I was doing. I really like that environment where I’m in my own world of drawing, but at the same time, I’m interacting with people. Over 3 days I gave out 93 flyers for Halloween window drawing in Brooklyn and got 8 jobs from it. I ended up doing 2 coffee shops, 2 smoke shops, 2 pizza restaurants, a liquor shop, and a 40 year old fish shop! It’s a really cool opportunity to have my drawings where people can see them too because I have so many drawings in my notebooks that no one ever sees except me. I draw them and then I turn the page and then that’s usually the end of the life of the drawing. So bringing folks in is a very integral part of my practice.

Clara Harlow: Speaking of that, can you tell me about your Mystical Magical Maths drawing events?

Ross Carvill: Mystical Magical Maths is a live interactive show where the audience gives me one animal and one object, and then I magically combine them together on a giant piece of paper. And while I’m drawing, I also tell a story and a joke. It was never meant to be like, stand up comedy, but people find it funny. It started as just a way of selling drawings, to be honest. In the beginning, I was doing art markets in Dublin, and had a spinning wheel that I made out of cardboard, a fidget spinner, and a hot glue gun. It had all these animals and objects written on it, and people spun it twice and whatever it landed on I drew on a piece of paper and then they purchased the original drawing. So it was just kind of a way of interacting with people, but then COVID happened immediately after I made the wheel, and then I was in my bedroom drawing on my own. And I was like, I wonder if I can still connect to people in a safe way while we’re all in lockdown, so I started going live on Instagram and recording my hand drawing while people commented with animals and objects for me to draw. I did 20 episodes of that during COVID times and I also took over two whiskey distilleries’ Instagrams and a screen printing studios’ Instagram.

Clara Harlow: Can you talk a little bit about the Irish children’s television show you’re featured on?

Ross Carvill: Yes, it’s a show called This is Art and we just filmed our third season this year. Each episode is a different theme and I have a segment where I come up with a piece of art to make with kids. The idea is that viewers are then inspired to make it at home. It’s been interesting, I had just come from COVID times when making during lockdown looked like making YouTube videos of my art process, sort of making my own TV show you could say, but it was a lot of work and editing. I was feeling negative about it because I was just putting so much time into them and there wasn’t much payback from it. And then the final video I did I was like, this is going to be the one! I spent a month going to multiple rivers around Dublin sourcing pieces of pottery and, unfortunately, plastic from the waterways and making this big fish mosaic out of it. I spent so long making the video and then I put it up and it barely got any traction. So I was like, frick this, and I didn’t make another one for ages, but that ended up being the video that the director of the TV show saw. I went from being very negative about it to being given this opportunity, which is interesting. I never planned on being on TV, it’s funny, it’s one of those things that just happened.

Clara Harlow: So your segment is Ross’ Art Corner?

Ross Carvill: That’s what we were calling it initially because I had a corner on the set, although on the new season there’s a different set, so I’m not sure if we can call it that anymore. Last season was cool though because we put a lot more emphasis on my segment, so we were actually out and about in the world drawing in Dublin Castle and drawing at the circus and drawing at the zoo being surrounded by lemurs. So I was able to bring a sense of place into the work with the kids which is cool.

Clara Harlow: What do you like about collaborating with kids?

Ross Carvill: It’s amazing to see their creativity and it reminds me of drawing when I was a kid. There are so many people that I meet that tell me they used to draw when they were kids. I always like the opportunity to be that person that provides encouragement that keeps them drawing. Even if one of the kids that I’ve taught over the years keeps drawing then it’s been worthwhile.

Clara Harlow: Yeah, that’s amazing. Did you know that I actually kind of have a complicated relationship to drawing?

Ross Carvill: Why?

Clara Harlow: I think it has something to do with how people expect you to be skilled at drawing and enjoy it if you’re an artist. I think growing up I felt a lot of pressure to do it in a certain way. But also the process and product of executing something formally impressive has always been boring for me.

Ross Carvill: Yeah, I feel like maybe a reason why a lot of people stop is because they’re comparing themselves to other people. But the other thing about when kids draw is that they are 100% drawing the way that they see the world. I mean, they’re drawing people and the person might not be a proportionate person, and they might have big blue arms, or they might have like a gigantic eyeball, and then a tiny eyeball, or like a giant pointy nose. You might think that’s not how you draw a person! But that is their view. And they’re not worrying about what other people are thinking about it. That’s a big part of it.

Clara Harlow: Yeah, totally. There’s a lack of self consciousness and they’re just leaning into intuition. I think the other piece of my wonky relationship to drawing is that I’m an artist who struggles working in solitude. There’s such an association with writing and drawing in solitude, but I’m so drawn to your practice because I think you really challenge these historical hang ups that I have with drawing as a medium.

Ross Carvill: The only thing it has to look like is whatever you want it to look like! You should come with me tonight to the Art Club group. It’s this evening at 7pm in Williamsburg.

Clara Harlow: Yeah, I remember I went to the Artists of the Met group with you once and I was surprised by how hard it was for me to sit down and draw for an extended period of time. I keep a notebook and I observe and make a lot of lists in it, but I hadn’t intentionally sat down and drawn something in so long. And I think it made me have to confront some blocks I have around drawing. It doesn’t come as naturally to me as a form of play, it feels obligatory. It really requires you to slow down and listen to a space, which I think I typically resist.

Ross Carvill: It’s the only time in the day I slow down, to be honest with you. I’m constantly like, go, go go and my brain is constantly like, go, go, go. It’s such a busy world that we live in, and especially in the city. But it’s really the only opportunity I have every day to just 100% slow down. It’s sort of time for me and it’s not always easy to give yourself that space for sure.

Clara Harlow: Yeah, I feel inspired by the way you push what drawing can be and do. It really feels like a form of conversation with your community. You’re using this medium that could be so solitary and insular and instead using it as a means to connect and collaborate. It reminds me of your Eddy Goldfarb drawing. Can you tell me a bit about that exchange?

Ross Carvill: A few years ago I watched a short documentary from the New Yorker about Eddy Goldfarb, this toy designer whose biggest hit was the chattering teeth toy. I appreciated him and his attitude towards creativity and I felt inspired to draw him. So I did, and then I found his Instagram page and messaged him the drawing out of the blue. I didn’t think he was gonna reply, but then his daughter did reply. I told them I’d love it if you could have this drawing, so I sent it to them and they sent back a photo of Eddy holding the teeth drawing.

That was like two or three years ago and I didn’t really think about it for a while. But then I was at the Brooklyn Flea Market under the bridge in Dumbo a few months ago and I found the teeth toy. I was so excited because this was the first time I’d actually seen it in person. And then I told the whole story to the guy working at the flea market and he thought it was cool so he gave me a discount for the story.

Clara Harlow: Can you tell me about all the meetup groups you’ve attended?

Ross Carvill: Well, there have been many, but the two I regularly go to are a drawing group in Williamsburg that meets every Monday night at a bar and Artists of the Met where we go to museums to draw, but we also go to parks and other places. Yesterday we went to Sleepy Hollow, where the Headless Horseman myth originated, to draw stuff. It was funny, it was actually like an unofficial collaboration between the two big drawing groups.

Clara Harlow: How is drawing with other people different from drawing on your own?

Ross Carvill: It’s interesting because my mission is always a very solo mission. I call my art days my hermit days, and I don’t really speak to many people. I’m very much a people’s person, but I always struggle letting someone do a part of my piece of art because it’s such a personal thing. Like, recently I needed help with a budgeting aspect of a project and it was hard to let somebody in, but when it’s somebody doing their own piece of art beside me, it’s different.

Clara Harlow: Like parallel play.

Ross Carvill: Yeah, it’s nice to have company and experience places together. It’s also interesting when we go somewhere, and we’ll all be drawing the same scenery–it’s just always amazing to see, like, 15 or 20 versions of how different people have digested and seen the exact same location.

Clara Harlow: Are you nervous when you go to meet up with a group of all strangers?

Ross Carvill: I’m a weird person that sort of feeds off those situations. I’ve always been intrigued by job interviews and starting new things. There are definitely anxieties, but I feel like curiosity overpowers the anxieties. But I also like being in a space where the connection is art. Having that boundary broken already takes away a lot of the anxieties of meeting a new person. You already know that you’re meeting somebody that shares a passion of yours, so you’re not starting from zero, you’re already starting with a deep connection.

Clara Harlow: Yeah, absolutely.

Ross Carvill: Yeah, that is a beautiful thing about it as well. Art is the connector between people from India, people from Ireland, people from Texas in these groups. Everyone’s from different cultural backgrounds, religions, upbringings, different everything. It doesn’t matter about any of that stuff. You can throw all that stuff out the fucking window because the only thing that really matters in that space is that we all are artists, we all draw, and we all appreciate and love drawing.

Clara Harlow: That’s your shared language.

Ross Carvill: Art is the one connecting factor. That’s what brought us all together and made us friends. You think it’s just a small drawing in a notebook, but it has a giant power.

Ross Carvill (he/him) is a freelance illustrator from Dublin, Ireland currently living in Brooklyn. Ross has been drawing every single day since he could hold a pen. He loves to draw everything from lobsters mixed with roosters to documenting a conversation with a stranger on the street. He has worked with brands such as Hopfully breweries, Dead Rabbit Irish Whiskey, Ilk clothing, Anti Social bar, SOMY, The Dubliner Irish Whiskey, 48 Ireland, Clay Plants, Tesco Ireland, RTÉ and Innocent Smoothies. Visit his website to see his projects and follow him on Instagram for updates.

Clara Harlow (she/her) is an artist, designer, and preschool teacher from Omaha, Nebraska. Her work weaves together community, intimacy, and play through experiential events and objects. She has collaborated with Four-D, Fire Escape, The Tom Collective, Lolo NYC, Sounds, and the Fabric Workshop Museum Shop. Clara currently lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. www.claraharlow.com

The Eyes Don’t Deny It: An Interview with my Dead Grandmother

– Something I think my grandmother would say

“Death would have had to drag me kicking and screaming because who the hell knows what’s waiting for you on the other end. But since I couldn’t tell my ass from my elbow, I didn’t even know it was coming for me.”

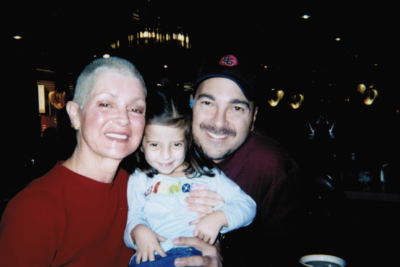

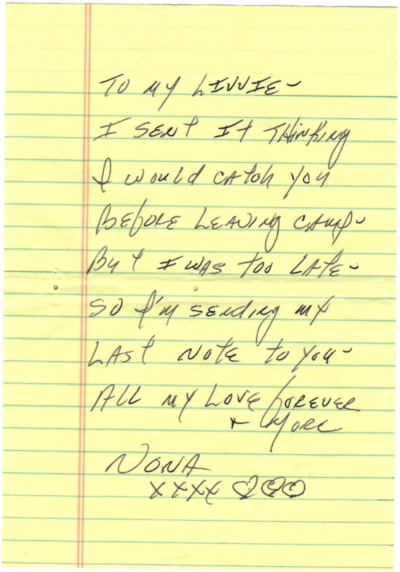

How can we blur the lines between life and death? How can we keep the memory of those we’ve loved and lost alive? How can we move past regrets and let go of the things we never got the chance to say? In an attempt to explore these questions, I decided to have a hypothetical conversation with my dead grandmother. It’s one of my biggest regrets that I didn’t ask her more about her life or have the chance to say goodbye to her.

I wanted this interview to be as close to accurate as possible so I sat down with my father, who knew my grandmother in many different contexts, to come up with her answers. I wrote down everything I wanted to ask her and, together, we talked about what we thought she might say. Once I had the interview written up, I called and read it back to him. Again, we discussed the answers and changed and tweaked until it was like we could hear her voice. Although this interview is a hypothetical, totally made up conversation I had with a dead person, it feels intensely real and I’ll treasure it as the last conversation I got to have with my grandmother and the one where I actually got the chance to tell her how much she meant to me.

Note: My grandmother, Nona, had a strong and wacky personality and I tried to capture that as best as I could but it’s hard to do someone like that justice.

Olivia DelGandio: Hi, Nonna.

MariAna Zachary (Nona): Hi, Livvie Pips.

[My grandmother used to call me Livvie Pips or Livvie Pipellina. When I asked my dad where she got that from, he said she referred to me as her little pip or pal and added -ellina, a common Italian suffix added as a form of endearment.]

Olivia: Can you tell me about your experience becoming an artist?

Nona: I always wanted to be an artist but my mother told me I had to be a secretary. It was the 50s so that was expected and I had no choice. I didn’t have the fire in me to reject it yet.

Olivia: What was your mother like?

Nona: She wasn’t a very nice lady. She used to dress me up to show me off but other than that, she didn’t care for me much. She always favored my brother and I never seemed very important to her. So, it made sense that when I wanted to be an artist, she couldn’t care less. I think I was really impacted from that lack of love even though I’d never say it.

Olivia: How’d you end up getting through that and becoming an artist?

Nona: It wasn’t until I was older and met Poppy [second husband] that I could really do what I wanted. Before that, I was a single mother to two boys with barely enough money to take care of them. I married Poppy in my 40s and he encouraged me to really start thinking about art again. So I enrolled at the Fashion Institute of Technology and I got a degree in interior design.

Olivia: I never knew you did interior design.

Nona: That’s because I did one job and realized it wasn’t my thing. I went back to FIT and got another degree in Fine Arts.

Olivia: I had no idea you had two art degrees. What did you focus on then?

Nona: I painted a lot and I really devoted myself to textiles. I made a lot of scarves and sarongs with silk screening, dying, and batik processes. Your dad would take them to work and sell them to all the girls in his office for me.

Olivia: That’s so cool. What’d you do once you graduated?

Nona: I got a job as a teaching assistant at FIT and I did that up until we moved to Florida to be closer to you guys. I loved being near you and your brothers but that move really fucked with me. I’m a New Yorker, Florida wasn’t the right place for me. I missed the city and FIT and having my own practice. My work was never the same.

Olivia: I never would’ve known you felt that way. I loved working in the studio you made in your Florida house, it seemed like everything was so great but I guess I was too young to know otherwise. Did you ever make work about those feelings or other emotions?

Nona: No, I could never go there. I’ve been too traumatized; there’s a lot you don’t know about my life and that’s how I wanted it. If I went there, I don’t think I’d ever come back. Even though I never talked or made work about it, I feel a lot. It’s the darkness in me. And the Scorpio energy. You get that from me.

Olivia: I seem to have gotten a lot from you.

Nona: Those eyes don’t deny it, you look just like me.

Olivia: You know, the only time I’ve ever seen you make anything emotional was when you were living with us when I was in high school. You were already pretty deep into Alzheimer’s and I got you to come and draw with me. You did a self portrait with something written on it about feeling lost. I felt so emotional watching you do that. There was so much I wanted to talk to you about but we had already been losing you for years at that point.

Nona: I guess my memory was so gone, I forgot about my rule of not being emotional in my work.

Olivia: I wish we could make something together. What do you think we would make if we could?

Nona: I wish we could, too. I think we would do some sort of self portrait project together. It’d be really dramatic and beautiful.

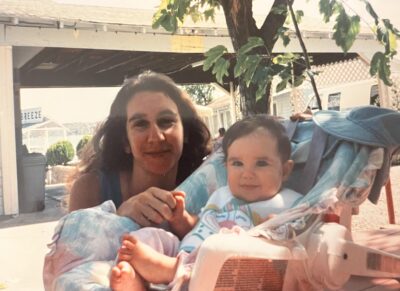

Olivia: I agree. You are the one who got me into photography. I still use the camera you got me over 10 years ago and I think of you every time I do.

Nona: I’m glad. The second you picked up mine I knew I had to get you your own.

Olivia: Nonna, what was it like to lose your memory?

Nona: Honestly, I was scared shitless. I’d come downstairs and stand in the kitchen for ages, having no idea what I was doing there until your father would come in and offer me something to eat or drink. I knew something was wrong for a long time but those last two or so years were the worst. I didn’t even recognize your father the last time I saw him.

Olivia: Were you afraid to die?

Nona: I think if I had my wits about me I would have been. Death would have had to drag me kicking and screaming because who the hell knows what’s waiting for you on the other end. But since I couldn’t tell my ass from my elbow, I didn’t even know it was coming for me.

Olivia: What do you think of what I’ve done with my life in the past few years?

Nona: Oh, I’m beyond proud. I’m your biggest fan. You know, it sucks for everyone that I’m gone but I think it especially sucks for you. We always had a deeper connection; I saw so much of myself in you. I regret that I really started losing myself when you really started to find yourself.

Olivia: But you helped me find myself long before that. Some of my favorite memories are of you taking me to get coffee (that I wasn’t allowed to drink) and we’d wander around the art supply store for hours together. You’d buy me whatever I wanted and then let me make a mess with it in your studio. I wouldn’t be the artist I am today without you. I regret being gone for the last year of your life but I am glad to have these memories with you. And especially glad that the last time I saw you, you still had enough left in you to know who I was.

Nona: I never could have forgotten you, my Livvie Pipellina.

Olivia DelGandio asks intimate questions and normalizes answers in the form of ongoing conversations. They explore grief, memory, and human connection and look for ways of memorializing moments and relationships. Through their work, they hope to make the world a more tender place and aim to do so by creating books, videos, and textiles that capture personal narratives. She is MariAna’s granddaughter and is the artist she is because of it.

MariAna Zachary (1944-2021) was a painter, photographer, and textile artist from Brooklyn, New York. She liked her grandchildren more than anyone else, smoked a lot of cigarettes, and had two degrees from the Fashion Institute of Technology. She was Olivia’s grandmother and is missed every day.

A Pause Anywhere is a Gift

-Judy Blumenfeld

“Everyone is a teacher, everyone is a learner. Even as therapists and analysts, we’re having an encounter with someone. It’s not that I’m this smart analyst and I know everything about mental health and I’m going to make you better. We’re trying to have a relationship and an encounter.”

My mom and I both recently had our Saturn Returns, (my first and her second). Your Saturn Return is when Saturn returns to the place in the sky that it was in when you were born. It happens about every 29 years and is known as a time for big life changes and growth. I was born during my mom’s first Saturn Return, when she was 31. I’m 31 now, and my first Saturn Return has just concluded, during which time I left Oakland and moved to Portland and started graduate school.

My mom went back to school when I was in middle school and got her Masters in counseling psychology and Drama Therapy. I think that her work in psychoanalysis has actually transformed our relationship in a big way. It feels easier to talk through complicated things now. It feels like there’s more room for trying to understand each other.

I’m really proud of my mom right now, and I’m excited for both of us because we are both doing the work we love and really want to be doing now. For me, that work is getting my MFA and teaching and deepening my understanding of my art practice. She just finished psychoanalytic training at the Psychoanalytic Institute of Northern California (PINC). This conversation took place just before her graduation where she read a paper she wrote to a big group of people over Zoom. In it, we talk about intergenerational trauma, Palestinian liberation, and the overlaps in our practices.

Luz Blumenfeld: What are you doing in your practice right now?

Judy Blumenfeld: I’m finishing this extensive psychoanalytic training that I’ve been doing for six years now. My graduation paper is a lot about my emergence, or becoming how I was thinking about myself as a psychoanalyst. And it’s a lot about my history, the history in the family, the history of trauma, how that lives in me.

One thing that a mentor told me once is that you’re a psychoanalyst everywhere, and I feel that a lot, it’s the way that I think in the world. Now, I think it helps my politics, it helps me interpersonally, and it helps me in my work. But I think what I’m excited about in my work, what’s been a kind of generative area for me, is groups and place, and that’s a lot of what my paper is about. What does it mean to be in community as a psychoanalyst versus what does it mean to be a psychoanalyst in a private setting?

And when I say institutional, I mean that I’ve seen that some people– we take training, and then we just live in this little world of private practice. And I’m very interested in not just staying in that little private practice world, even though I love my work with my patients.

But, I feel like it’s about the intersection of the social and psychoanalysis. And that’s where I was thinking about your work, Luz, and how just the little I know about art and social practice, is that there’s something very similar there, like about the intersection of something with something. So how do we understand these spaces that we’re all in? And I think yours is from, like, an artistic aesthetic, but also a historical perspective. I see a lot about that in your work. So with psychoanalysis, too, you take a place, and you try to deeply understand a place, but I’m interested in the places where most people are receiving help.

Right now, I’m involved with a community psychoanalysis project that I’ve been part of since the beginning of the training. And it’s an emergent project of psychoanalysis. It’s about community and psychoanalysis and the intersection of the two. I first did a project that was at an agency that did work with refugees and asylum seekers. And what’s different about this is that instead of a person being my training case, because we talk about cases in my field, the whole place is my case, and also I’m their case. I meet with a group of people who are in community mental health, people who are very analytic but have not had formal psychoanalytic training. We dissect and talk about the intersection of what’s happening in that place. And the social, what’s happening socially about immigration and refugees. My colleague and I did what’s called a “case conference,” where the therapists at the agency present their cases to my colleague and I, and then we present that to a group of people. So it’s like groups thinking about groups.

Luz: Yeah, that’s really cool. I can already see a lot of places of overlap in our work. I’m also really interested in place; in site-specific, place based work, and work that is durational. I think what you’re doing is really specific to that place in that time, to being in that time together. Yeah, and that’s not something you can recreate– that’s really interesting to me.

Judy: It’s a moment, yeah.

Luz: What you’re trying to do with that moment is really interesting.

Judy: It’s also the fact that it’s a historical moment that enters into it for me. And now I’m doing a project that’s fascinating– So we’re not in a mental health setting. I’m co-facilitating a group at the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office. These are the people who try to represent people who have no money and who are imprisoned, and try to get them out.

Luz: So what is your role there as someone who is from the mental health side of things?

Judy: Right? Excellent question. Really, just to try and help these people with their trauma and to create some kind of space for them. And it’s emergent. With the community psychoanalysis we never come in with a prescribed idea, like dropping psychoanalysis into a place. Instead, we co-create something. It’s early in the project now, but we’re trying to see what these folks need to help them do their work, to help them with whatever their themes are. So we don’t have anything prescribed that we do except that we hold a space.

I’m excited about the intersection of psychoanalysis and the world. I’m also involved with radicals in psychoanalysis and many of us have been talking about Palestine. I’m going to be starting a study group with other people who are in mental health about Palestine.

Luz: That’s good. I’ve been thinking lately that we need to be creating in-person spaces to meet and talk about everything instead of like, pushing it down and trying to just do our life. Because that’s dangerous. We need to talk to each other. In terms of organizing, too, it seems like no one knows where to start, and everything is so connected. And the way that movements have started historically is people being in the same place talking to each other.