Conversations on Everything: Interviews Fall 2021

On Grief, Storytelling, and Building Little Altars Everywhere

“When you’re in the space of death, people dying, and fragility, things become very clear. It’s a very real sacred space and I think it’s the closest we get to being truthful about life and emotion.”

STARR SARIEGO

I met Starr somewhere in my teenage years through the deep friendship she shares with my grandmother. Right away, I sensed her kind, compassionate energy and this was only exemplified when I learned about the kind of artist she is. Through following her work over the years and seeing her occasionally, I learned that our interests overlapped in quite a few areas, the most notable being photography and storytelling. It was for this reason that I decided to interview her, however it became clear pretty quickly that we had even more in common than I thought.

Over the last few years, the topic of grief has been heavy on my mind and my artistic practice. Since starting this program, I’ve especially been thinking about ways we might be able to reshape our environment to be more supportive of those who are grieving. When I told my mom that I had decided to interview Starr she asked me if I knew how her and my grandmother met and I realized that I actually did not. She told me that Starr and my grandmother had shared a chunk of time on the hospice ward, my grandmother as a social worker and Starr a volunteer. So our proximity to grief and loss became a new theme connecting me and Starr. What follows is a conversation on grief, what we keep from those we’ve lost, and how we can use art to uplift the tender humanity that is all around us.

Olivia DelGandio: I actually just found out that you met my grandmother because of your shared time working in hospice, I had no idea. Can you tell me how you got involved there?

Starr Sariego: So I started working at hospice as a way to sort of give back in my personal family history. I lost a sister about 16 years ago to cancer.

Olivia: Oh, I’m sorry.

Starr: It was tough because it was my first real experience with that sort of loss. And then my second sister passed away and then my mom passed away. And we used hospice for all three of their passings. And so when I got back to Miami, I felt like, gosh, I really want to get involved. And I was not interested in being committed to one family. So the other option was to work on the unit at the hospital. The hospice there had a whole floor. So I met your grandmother, who, you know, fast became like a dear friend to me. And she made such a difference in my life because she really taught me about grief and holding space for people going through it. And I think, you know, as women, certainly culturally, we are trained to fix health. To repair. You know, I could keep going with the adjectives, but you get the idea. And I learned from your grandmother that the best thing to do here is to be an open receptacle for that person to, you know, lead the way through their grief. It was just good practice for life, you know?

Olivia: Yeah, for sure. My grandma is really good at that, at holding grief, for sure. But I mean, I’m so sorry to hear about all of that loss. That is so much. That’s so, so heavy.

Starr: Yes, it was.

Olivia: Was there any overlap between your time working in hospice and your art or any overlapping interests in that realm?

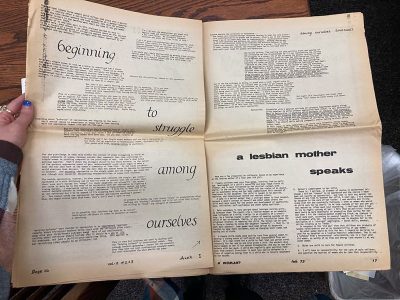

Starr: It’s interesting that you ask that question because I always wanted to do a photography thing on hospice. I was already doing photography and I had done the first photography project on women with disabilities called the Bold Beauty Project. I don’t know if you looked at my website, I have all the projects there, the projects that I’ve worked on. So I think they were overlapping and I was very called to do something in hospice, but I never did because I was worried, you know, I just didn’t want to deal with all the privacy issues and all of that.

Olivia: Yeah, definitely. So what do you think a project on grief and hospice would do or challenge?

Starr: I think that what happens is, when you’re in the space of death and people dying and fragility, things become very clear. It’s a very real sacred space, and I think it’s the closest to being truthful about life and emotion. This space of grief and handling grief, it is a very deeply truthful space. It’s as honest as you can be. You know, I think in real life, you’re out in the world and you’re distracted by your children and your friends and going out and whatever it is you do in the world. But when somebody is dying, it’s like all those facades are ripped away and it’s a very truthful space to be in. So I think it’s an amazing place. You know, I think a lot of artists do their best work when they are troubled, you know, writers, poets and musicians and painters. So yeah, it’s a great motivator for art.

Olivia: Yeah, I agree. And you know, I’m sure you saw recently that Scott [my uncle] passed away.

Starr: I can barely handle it. I called your grandmother. I’ve called her twice. Then she called me and I was on this trip and I haven’t called her back yet. Yeah, I mean, I can’t believe what your family’s been through.

Olivia: Yeah, me too. But I feel called in this moment to make something about it. And so I’ve been thinking about that a lot, like the space and the truth that’s coming out of this moment. And like the ways, especially because I’m so connected to my mom and my grandma, the ways that we’re all existing in this time, in this space. So I don’t know what it’ll be yet, but I think something.

Starr: Yeah, and I think you write beautifully, I’ve seen other stuff you’ve written, and I think that, you know, maybe in speaking to them, something will come alive for you. There is this thread of connection that’s very strong between the three of you and there’s something about what gets handed down. You know, the whole idea of epigenetics, where even another generation’s emotional experiences have an impact. In fact, I was just talking to my daughter-in-law about this. She’s sitting here in the car kind of smiling because we were talking about the things that had happened in her family two generations above her. Hmm. You know, it’s like in your case, I think it’s a very strong, positive thing. And in her case, it was sort of a very negative damaging thing and the effect of how that affects families positively or negatively, especially in the grief space.

Olivia: Yeah, for sure.

Starr: You know, she [daughter-in-law] lost her grandfather earlier this year to cancer. But out of that loss came a lot of truths in her family. And I find that that does happen. I don’t know if there have been more stories about your mom’s family and your grandmother’s family, you know?

Olivia: Yeah, definitely. I mean, and it’s funny, really funny that you mention epigenetics because I had a conversation with a classmate yesterday, literally about epigenetics and grief.

Starr: It’s a huge thing, it’s a huge thing. I mean, I don’t know what’s happened in your family, but— I think I met a poet once in California who was Jewish and her parents had been in the Holocaust and survived. And what trauma came to her even though she wasn’t in that trauma?

Olivia: Yeah, I’ve been wanting to read about ancestral trauma and such. I’ve been thinking about that because my mom’s grandparents on her dad’s side fled Germany during the Holocaust. And so wondering, yeah, how that’s been passed down, for sure.

Starr: Very interesting. And then interestingly in your family, like how intensely cancer has ravaged your family. And in my family too, not to the extent of yours, but definitely, you know, in my immediate family, it’s like, wow, yeah. And then my mom’s whole line of family all died of cancer. So it’s very interesting.

Olivia: There’s a lot there that I want to read about and learn about. It’s definitely a field and theme that I don’t know enough about. So I want to do some reading.

Starr: Well, you have plenty of time in your life. The universe will just give you those life lessons.

Olivia: Oh yeah. Okay, let’s see what other questions I have for you. So you work mainly in photography and storytelling and I’m wondering what experiences, moments, or memories led you here, to the way that you tell stories. What were some influences on your practice?

Starr: So interestingly, every project I do gets birthed out of my own personal experience. I don’t know if that is true for a lot of artists, but I think in my personal experience I have to have a deep emotional connection to the subject matter. So with the women with disabilities project, one of my friends had a disabled daughter, but I didn’t have a lot of experience with a lot of other people with disabilities. Even deeper than that, I think it’s really underrepresented in communities, you know, they aren’t seen, generally, or understood in our cultural lives. And so I think women with disabilities are really infantilized, and I did this project and I found out these women were sexual and had relationships and children and had big jobs and had been through tremendous trauma. And then the women in prison, the same thing. It was like this deep dive into the other and the disenfranchised, in a way. Recently, I started therapy again, and I think that a lot of my interest in that comes from my own feelings of having been “other” in my life. And instead of like seeing that, I’ve been looking for it outside of myself.

Part of the Bold Beauty Project, a visual arts exhibit that featured women with varying disabilities. Digital photograph. 2016. Miami, Florida, United States. Photo by Starr Sariego.

Olivia: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Well, it makes for some really beautiful work.

Starr: Oh, thanks, honey. Thank you.

Olivia: Actually, the program that I’m in had a project at a prison in Portland, Oregon, and I’ve been thinking about that a lot and maybe wanting to get involved in something like that. What was your experience there like?

Starr: Oh, it was very crazy. I mean, the biggest takeaway is that, since the 80s, the population of women in prison has risen 700 percent.

Olivia: Wow.

Starr: And of all the women in prison, like almost 90 percent, I think the number is 88 percent, have been physically or sexually abused by the time they’re 18. So when you go into that population and you meet these women and there are a lot of white women, more white women than you would expect, you realize these women could be my sister, my neighbor, my auntie. You know, somebody that you would know, except for this event that had happened to them. So, you know, that was my experience. But for me, you know, you were asking about the narrative portion. I really think the story, along with the image and the person telling their own story, has such tremendous power. Yeah, it’s like, This is how I want to be seen in the world. This is the story I want you to know about me and how I got to where I am. See my humanity. That’s my thing. I want people to see that humanity, you know? To remove the otherness, maybe.

Olivia: Yeah, that’s a good way of putting it. I saw on your website that you said you’re mainly self-taught. Can you tell me about that?

Starr: Yes, yes. I came to photography really late. I think I’ve always been visual and creative and artistic at home, or whatever. I like my environment being pretty in a way that suits me, not to suit another person or somebody else’s idea. In fact, I think my space is kind of a little quirky.

[Daughter-in-Law jumps in]: Yeah, your space matches your soul. You select things that are beautiful to you. Things you love to touch, you love to look at. Right?

Starr: Right, right. I like to talk about everything on my wall. Yes, and everything in my home has a story; the thread of meaning and the value things hold. It’s like the emotional core value that Little Altars Everywhere came from. When I was stuck at home by myself during the beginning of the pandemic, I realized I really cling to emotions, the past, and ideas from the past. I’m really working on evolving from that. The narrative, I think for me, is always important to the story of a thing, of a human, of an ornamental object. I always tell people I have a lot of dead people’s things in my house.

Olivia: Oh yeah, me too.

Starr: Not in a morbid way. But I’m comforted by having those things around me.

Olivia: Yeah, me too. Yeah, for sure. I just made a little altar and I put, you know, photos and I have all of these little objects and stuff. So, yeah, totally.

Starr: Take a photo with your phone and text it to me.

Olivia: Yeah, definitely.

Starr: My whole house is sort of like little altars everywhere.

Olivia: I love that. Yeah, I love that phrase.

Starr: Yeah, and it’s true. I have little collections and things everywhere. I have this wooden angel and underneath it, it’s like my offerings to her, little bits of mica I find on hikes and beautiful leaves.

Olivia: Oh, that’s so good,

Starr: If I remember, I’ll take a picture and send it to you.

Olivia: Yes, please.

Starr: Yeah, it’s like honoring the beauty and little things you stumble across every day.

Olivia: Definitely. So what’s one of your favorite things in your space like that right now?

Starr: Oh gosh.

Olivia: Or maybe not one of your favorites. Just tell me about one.

Starr: Well, I value this portrait of my grandmother that was painted in 1942 and it’s a very beautiful, very sort of bougie, antique looking portrait. It’s like a classic vintage portrait of somebody that you would hang on your main wall and be like “this is my great grandma who built this house.”

Olivia: Yeah, that’s so cool.

Starr: That’s very meaningful to me. And then I have two portraits of my children, if you text me and remind me I’ll send you photos of them because they’re quite lovely. Ok, well, so those things are very important to me and some furniture that my dad had made for me.

Olivia: Oh, that’s beautiful.

Starr: Yeah, that I cherish.

Olivia: That sounds like a lovely space.

Starr: Oh, thanks, honey. Well, honey, if you think of anything else, you can always just text or call me tomorrow, OK?

Olivia: I actually have one last question. Maybe kind of random but are you someone who remembers your dreams at night?

Starr: I do sometimes, and sometimes I don’t. I was getting ready for this trip and I was having a lot of anxiety about it. I had a very specific dream. I’ll tell you my Halloween dream, which is really crazy. Ok. You know, I photographed a lot of LGBTQIA folks for my latest project. And so I had been photographing drag queens. And so in my dream, I was with a friend in a drag queen’s studio or shop that had amazing dresses. And I had eaten a hamburger, which I never eat red meat, but I had a hamburger recently, like maybe two days before the dream. And in my dream, the friend I was with found the most beautiful gown, cut out to the stomach with just thin strips of fabric that showed her beautiful, flat stomach. And she looked gorgeous. But I couldn’t find a dress that fit me. Every dress I put on, I couldn’t pull the zipper up. It was like an anxiety dream. Finding the right costume in the shop of the drag queen. And I was worried about my belly. So there you go.

Olivia: That’s so funny.

Starr: It was very specific. I do sort of remember some of my dreams.

Olivia: I’m just asking because lately I’ve been thinking a lot about dreams and using dreams in artistic practice. So I’m just always curious about people and their dream life.

Starr: Have a dream journal next to your bed, perhaps.

Olivia: Yeah, I do. I write them down. I actually made my grandma start doing that because I want to write down my mom’s, my grandma’s, and my own dreams at this point in time. So she’s been telling me her dreams lately.

Starr: Oh, that’s so amazing. Wow. If that doesn’t suggest a project…

Olivia: Yeah, that’s what I’m thinking about. And actually, last week, all three of us had dreams about dogs for like a week straight

Starr: Oh, that’s so funny.

Olivia: So it’s just on my mind.

Starr: It’s so strong, the connection between the three of you, you’re even dreaming in triplicate.

Olivia DelGandio (she/her) is a mixed media artist interested in human connection, what it means to be tender, and the joy/sorrow dichotomy. She graduated from New College of Florida with a degree in Sociology/Gender Studies and is currently working on her MFA in Art and Social Practice at Portland State University. She finds solace in creating through and for grief and is currently thinking about how grieving can become more of a community practice. She likes to create books, photos and videos for and about the people she loves. The hope for these projects is to make intimate moments and connections more visible. You can find more of her work here and find her on Instagram here.

Starr Sariego (she/her) is a native-born Miamian and now calls Asheville, NC home. She is a passionate and mostly self-taught photographer. With over 15 years in photography, she’s found that her interest lies in photographing people. Whether it be a family portrait, a headshot, a business client or an event, making that human connection to bring out the best in subjects is her superpower. She is committed to getting the most out of every photo shoot for the benefit of the subject and the cause. You can explore more of her work here.

The Art We Value

“I have this eye for things.”

MICHELLE GRIMES

I have been reflecting on how this time two years ago, I wrote about the Jantzen Beach RV Park —a community that I still live in today— in the 2019 SOFA Journal: Exchange issue. I was new to both the RV lifestyle and the Pacific Northwest, and very preoccupied with getting acclimated to a new culture and way of operating in graduate school. My first interaction with a resident when I initially pulled into the park was with Michelle Grimes, my next door neighbor. She has been a huge influence on my time here and taught me how to look out for other neighbors and to be a better listener within my artistic practice.

Because I am a sentimental person, It’s only natural that I begin my final year of graduate school with an interview with Michelle and her granddaughter, Cece, to talk about art and what we value within our lives and our tiny homes.

The scope of my practice has scaled down to my individual relationships with my neighbors, and cultivating conversations of exchange, for survival. My neighbors and I lived through toxic forest fires that required us to keep within our small confines, ice storms that left many of us without power while tree limbs shattered our windows, and finally within a global pandemic that shut down programs and businesses that we rely on within Hayden Island.(1) We have relied on each other as support systems whenever someone needed help— wandering out of our RVs to lend a helping hand.

In October 2021, I initiated a project called “The Art We Value,” a project where I ask my neighbors to share a piece of themselves by selecting an item from their house to talk about using the lens of art. I take their picture and then draw them together with that item. When I approached Michelle to participate in the project, she was interested, but only to have a portrait done of her granddaughter. For the almost three years I have known her, Michelle has lived through so much stress and grief with her family; I wanted to convince her to get a portrait of both of them together. I argued that it would be a valuable thing to look at and reflect on for years to come.

She loves to see my dogs (and they her), so we found many great opportunities to chat in passing. Michelle would share her passions for teaching herself about stocks and NFTs, or finding great deals on groceries or artwork at garage sales. While talking about the project and setting up times, she would casually ask me for permission to spray out the leaves in my driveway, or clean up my garden box, both of which I’ve neglected over the last few months. Since the death of a parent figure in my life in February 2021, I had slowly pulled myself from my passion of gardening and allowed things to go wild. Since we live so closely together and her kitchen window overlooked the jungle of vines and leaves I left while I was healing my broken heart, she asked me to allow her to help. I agreed if she allowed me to draw her.

We set up a time when I could come over to her place for our photo shoot and a brief conversation.The conversation ended up being three hours; we talked, laughed, and she pulled out notes and artwork she usually keeps tucked away. We’ve continued the dialogue since that time we spent together, and have decided that once the portrait is completed, I’ll turn it into a non-fungible token (NFT) for her. We agreed that she could receive royalties on her likeness every time it was traded, much like a stock, in hopes to support herself and her family in the future.

Hayden Island, Oregon. Photo by Shelbie Loomis.

Shelbie: Okay. Tell me a little bit about the piece that you selected that I’m going to be drawing you with.

Michelle: The piece I selected is a photo I took of my son, my daughter-in-law, and my granddaughter. She was maybe two, two and a half, and we were walking in downtown Portland, Oregon. And something just tells me like, Hurry, you know, take this picture because this… you know…

Shelbie: So it looks like it’s a candid picture. They didn’t know that you were taking it. It’s like this perfect moment where Cece is just learning to walk. And you guys are out on a family outing. And so you had it printed in black and white. So tell me about that.

Michelle: I actually do a lot of black and white. I think there’s something about bringing them here [into my house]. There’s something about black and white. It’s timeless.

Shelbie: So you, I’m just noticing that you have a lot of artwork in here.

Michelle: I have a lot of artwork! Yes.

Shelbie: So tell me a little bit about how you select the artwork you keep, because this [gestures to the living room] is curation. You’re a curator.

Michelle: Right? So that’s— I don’t know, what do you call those, caricatures?— Anthony [husband] and Alex [stepson]. And then those are pictures that Alex drew when he lived with us. He actually drew those freehand. He’s very talented. You know, he also made that whole boat picture thing over there that you could go look at, if you want. Yeah, there’s tons of artwork.

Shelbie: What I’m interested in is when you live in an RV, you have to be very selective with what you put in the space. And then you have to justify the value right now. You and I, we don’t move our RVs, right? So we don’t have to think about it like some people who are travelers.

Michelle: Snowbirds, like Gary and Jeanie, right, yeah.

Shelbie: Right! So the towing capacity is different for us. But yeah, I’m interested in how you keep your space and how you select the art that you have.

Michelle: So there’s a story behind those two pieces. If you want to go look at that one on the floor, you can take pictures of the one back there. We have to move. I have tons of art and I hope someday [it brings value]. But to be honest with you, Shelbie, I’m very “art like” but I can’t draw, like, stick people. I can’t draw anything. [However], when I go thrift shopping or something, I have this eye for things. Like I have a $165 Italian wallet that I paid $1 for. [I just have] this weird eye about things.

Shelbie: I definitely agree with you. I’ve noticed just by the way that you even work through the yard. It’s like you have an eye for form. You see the way that things kind of transition, and so, you’re kind of curating, I just feel like you’re a curator. If I were to give you a title, I think it would be a curator.

Michelle: What is the actual definition of a curator?

Shelbie: I define a curator as a person who makes visual or artistic decisions on how to place things, or directs how to place things together.

Michelle: Yes, so yes, if I had to do life over again, I’d probably be something like an archaeologist. Or, believe it or not, in the last six weeks I’ve been learning the stock market and cryptocurrency. I have notes on my bed and watch both TVs blasting. I have the stock market on all day and I can’t believe how much I’ve learned and taught myself.

Shelbie: We need more people who know the stock market and the financial world. It’s actually that we need more women.

Michelle: It’s hard to figure it out. And so I was trying to find it for myself. I re-downloaded my Twitter, so I could follow things on Twitter. I read all these notes because I did go to college. I mean, notes from hell. One of the Bitcoins is on the real stock market now. It was the first Bitcoin EFT and of course, then this guy comes on, he’s like, Yeah, well, you know, they, the old school people of stock market, need to learn that it’s crypto currencies, really a big deal.

Shelbie: Yeah, it’s really interesting because you have a lot of people that are older… Older investors who want to keep gold as a standard wealth investment.

Michelle: What is that I have? Oh, there was a story behind it [image above]. Her name is Marcia Brown. Looks like this is an anonymous woodcut…So like I told you, I just have this weird eye or whatever. This [artwork] was in Goodwill in Wilsonville, probably four years ago, before I moved here. [These woodcuts] were numbered. They were [by] the same person, blah, blah, blah. And I’m like, I’m just buying them. So then I go home and I Google all this stuff. Well, come to find out this lady here is famous. She is. I can find all this stuff. I have notes everywhere. I remember. She was a children’s book… What do you call that? An illustrator? Yeah. She also has, there’s the Marcia Brown Museum in New York. I don’t know where my notes are. I don’t know where the big note is where I wrote it down, you know? Right here, University of Albany, New York Department of Social Special Collections.

Shelbie: So she has been collected by the University?

Michelle: Yeah, they actually have a museum there because she was a famous children’s books illustrator.

Shelbie: Interesting!

Michelle: And because you’re artistic, you caught those in my house, which nobody ever does.

Shelbie: Really?

Michelle: Yeah. And I’ve been meaning to call them for like three or four years. Yeah. And then I’m like, but I like them. But then I want [them] to go to the museum.

Shelbie: Well, here’s the thing. You could at least have them appraised, because what you could do is, you still have ownership over them. But depending on if they’re looking for this special collection, for example, you could send them to be a part of a show. Or they can just appraise them, so that you know where they are and how much they’re worth.

Michelle: I like to watch Antiques Roadshow all the time. I get really upset when there’s like this 200 year old, you know, Cherokee blanket that belonged to some tribe, I feel it needs to go back to the tribe. Sure. That’s how I feel. Sure. So if this lady has a museum in New York, and this can be hung in that museum, and there’s something about her, that’s why I want them to go back.

Shelbie: I can understand that!

Michelle: And that’s another thing. Another reason why I don’t get rid of some of my stuff, you know, is because my son wants to throw everything away. Cece’s dad and I had this really big picture in my room at their house. I told them I don’t give two shits about you throwing away my mean uncle’s barbecue or all that stuff, [but] you are not going to get rid of that picture up there, ever. Right. One thing I’ve learned about watching Antiques Roadshow, almost every single episode, 99.99% of the time, oh, somebody in their local hometown appraised it and didn’t know what it was worth. They came to find out, it’s worth half a million dollars. Right. And you know how pissed I would be if something I had and dropped off at Goodwill was on an Antiques Roadshow special? I would lose it. You know? Yeah. So that’s probably why I just hide it all over.

Shelbie: Well, I think it would be kind of cool for you to know what you have, and create an inventory list.

Michelle: Well, I have so many health problems now and I’m sick all the time and everything. If you don’t see me outside [it means] I’m sick, you know. And just, yeah, the bills, the stress, you know, life— something always breaks our income. I just gotta figure something out. You know, try to make money. Yeah. [Looks at Cece] Grandma’s been addicted to the stock market thing.

Footnotes:

(1) Hayden Island: an island that is between Vancouver, Washington (South) and Portland, Oregon (North)

Shelbie Loomis (she/her) is a socially engaged artist and illustrator. She makes projects and drawings with communities and participants about complex grieving, alternative housing, and exchange culture through times of crisis. Originally from Santa Fe, New Mexico she now lives in Portland, Oregon.

Michelle Grimes (she/her) is originally from Los Angeles. She loves to cook, garden, and clean and spend as much time with her granddaughter by taking her everywhere and doing things with her.

Healing in Practice

“I think about joy being something that doesn’t come from the outside and joy is not something that we assume is permanent. It’s something that we are trying to be aware of. I think that recognizing that the possibility for joy exists within me changes my focus. Because I’m looking less directly at how I can succeed, how can I win? I think that’s a really useful way to think about it.”

DARRELL GRANT

The Black Box Conversation Series (BBCS) is a podcast and radio project launched in 2020 in response to the pandemic. BBCS aims to create a safe space where people of color can hold meaningful conversations centered around their human experience. My practice often uses conversations and storytelling as primary tools to connect us. I’m interested in co-authoring work that centers the need for reparations to address the injuries inflicted on the African American community. For SoFa journal, I’m sharing a conversation about healing with PSU jazz professor and composer, Darrell Grant. This interview originally aired on Portland State University’s radio station, KPSU, on November 11, 2021.

Kiara Walls: Hello everyone, my name is Kiara Walls and this is the Black Box Conversation Series. The Black Box Conversation Series aims to create a safe space where people of color can hold meaningful conversations centered around their human experience. Today, I will be speaking with professor Darrell Grant, and we will be talking about healing. So to kick things off, I will let Darryl introduce himself and then we’ll go into some of the questions.

Darrell Grant: I’m Darrell Grant. I’m a jazz pianist, composer, and a professor of music at Portland State University where I’m entering my 25th year of teaching. I’m also associate director of the School of Music and Theater at PSU. I direct a new program in the College of the Arts, it’s called the Artist as Citizen Initiative, which is an interdisciplinary pathway/intersection between the arts and social justice.

Kiara: Awesome. I’m super excited to be talking with you today. We’ll just jump right in. The first question is, what does healing feel and look like to you?

Darrell Wow, well, let’s start with the easy question. The first thing that I think of is self-knowledge, because I think without that, it’s really difficult to approach the idea of healing. Self-knowledge, for me, has meant coming to understand myself as a Black person, coming to appreciate the unique experiences that I have had, and both the challenges and the successes. I think then coming to see that it’s okay for me to be uniquely myself, both, you know, as an individual, but especially as a Black person in America. That has been a big part of the healing is, you know, self knowledge and then self acceptance. After that comes the process of sort of working through all the things that come up, trying to find contentment and satisfaction. I mean, happiness is kind of a big ask. It’s something that comes and goes, but I’m feeling like this way of feeling content, you know, sort of content with my lot in life, with my path in life. So those are the kinds of things I think about when I think about healing.

Kiara: Thank you for that. I just want to touch back on how you’re talking about being content versus being happy, because happiness is fleeting. There’s this idea that the main goal is just to be happy, and happiness is an emotion that comes and goes. What I think about is joy, and being able to cultivate joy. It doesn’t necessarily have to be tied to anything that you’re working towards, but something like a framework that you create every single day. You find joy in the little specialties of life, you add value to that, versus something that’s external and also something that takes a certain amount of work to get towards. Then the idea is that you’ll be rewarded with feeling. In my opinion, healing is also tied to happiness. Before I had a better understanding of what healing was for me, I used to think that it was more about when you get to a certain point in your journey that you no longer deal with any bad things.

Darrell: Right! Like nothing goes wrong, it’s all good. You have finally crossed over!

Kiara: I’m just like, WOW, that’s a really tall order. I think it’s also not sustainable. I mean, to be human is to make mistakes.

Darrell: Yeah. It’s to be imperfect. I mean, that’s nature, you know, it’s really funny. I was just watching Oprah’s interview with Will Smith, and he has just written a new memoir where he talks a lot about this idea of joy. I know a lot of African Americans, especially artists in my field who are always aspiring, always reaching, always stretching, and always trying to get to someplace. On the outside, a lot of that looks like success. Some of it looks like security. I think about joy being something that doesn’t come from the outside and joy is not something that we assume is permanent. It’s something that we are trying to be aware of. I think that recognizing that the possibility for joy exists within me changes my focus. Because I’m looking less directly at how I can succeed, how can I win? I think that’s a really useful way to think about it.

Kiara: Right. It’s about giving yourself that agency to experience that feeling, you know, giving yourself that power versus always having external validation, because I feel like external validation is nice, but what happens when you don’t always have that type of energy around you? Not to say it doesn’t feel good when you get the external validation, but it’s not going to be a situation where it’s around you all the time.

Darrell: Or you wear yourself out constantly seeking it. That’s what I think is interesting hearing Will Smith talk about it in reflecting on that myself, that there’s this really interesting and insidious way where you keep chasing accomplishment. It’s never quite enough, you get it, but it’s not. It’s just, Oh, but if I could just get that, oh, this is nice, but if I could just get that one thing. I always thought I’m not really chasing money or I’m not chasing things that are considered vain. It looks like I’m really trying to do good things, right? But if I’m still seeking that validation, then I’m ignoring the times when I really need to be stopping and doing nothing, just sitting, just restoring myself for the thing that I’m really supposed to be doing, rather than doing this one other little thing to try and get the validation. I’ve noticed this act of chasing your tail a bit.

Kiara: That also makes me think about the energy that one puts into their work. When you aren’t chasing external validation, you’re truly creating the work because it’s coming from your heart and your soul. There’s a level of transparency and an organic element to it that is seen within the work.

Darrell: I don’t know though. I mean I hear what you’re saying, but I also feel like it won’t necessarily be perceived outside of yourself. Do you know what I mean? Because I think that one of the things that we get good at when we are seeking validation is, we get good at doing things that get the kind of recognition that we’re looking for. Right? And if you desire to be validated for being selfless, you get really good at doing work that is admired for being selfless. The problem is if you’re really supposed to be doing something else, like if your own path to joy or fulfillment involves something else, other people may not recognize that because you’re not hitting those buttons that they’re used to seeing. I think that as an artist, I find that especially true. It’s like, sometimes you really do have to go inside and when people ask you what you’re doing, you got nothing to show you can’t say to them I’m trying to figure some stuff out. I’m just working on some stuff. Because they’re like, “When are you going to play a show? What are you going to do?” And then I say, “I’m not sure because I’m really trying to work some stuff out.” This kind of dialogue does not get a lot of validation. So I think it can be lonely. So that’s when I think what you said about the joy, finding the joy and doing it for those reasons, is really necessary because it can be a dark lonely place sometimes.

Kiara: I totally understand. It’s funny because people can’t always see the work that you’re doing or the work that you’ve been up to and all of the things that you’re processing. So it just boils down to giving yourself that validation, and allowing yourself that space to process things and not be worried about what anyone else is saying or their expectations. With that said, what are the expectations that you have for yourself? Can you meet those expectations and call it a day? Can you describe any day-to-day rituals you practice that contribute to your self-care?

Darrell: Wow. I wish I could. To be absolutely honest with you, I need to embrace more of that. I am a jazz improviser, and my dream for myself has always been to have a life that was completely absent of routine. It’s interesting because there’s a certain number of things that you can get done in one big gesture. But oftentimes if you’re trying to do something that’s really large, you have to break it up into pieces, which means you have to go at it for many days at a time. I just premiered an opera in September (Sanctuaries) that I’ve been working on for four years. It took four years from start to finish, from the conception of the idea to acquiring the commission. Then it was delayed a year and a half by COVID, which I just took as an opportunity to rewrite it. I thought, I can make it better, and in that there was a need for this regularity. I’ve worked a lot over the course of my life trying to become a person who can embrace doing things incrementally, and more so now, iteratively. I’m realizing now this is just the first draft, get it done, throw it away and then start on the second. Once I get to the second, good; fix it and get to the third. I’ve become more of that person, but I still, in my heart of hearts, I just love surprises. I love not doing the same thing or at least feeling like I’m not doing the same thing. It’s been hard to cultivate rituals because rituals by their very nature are things that you repeat that you do on a regular basis and that you focus on.

I think one of the things that I’m doing now, actually that’s fairly recent, or at least my sort of returning to, is just breathing. Really taking the time to notice my breathing. My wife is reading this really cool book called “Breath,” which talks about the science of breathing. I just realized, Oh, that’s something that I can just do. What’s useful about it is that it counteracts knowing exactly when I have to do it. For example, I turn on NPR and then the radio comes on and I start to get this tightness on my chest as they start talking about how terrible the world is. It’s like, Okay, let’s breathe. Now. This is good. I recognize this is the time. That’s something that I’m looking at cultivating. I think the next thing I probably need to cultivate is a ritual around sleep and rest because all my life I have resented the need to sleep. If I didn’t have to sleep, I would never ever sleep. You can’t do anything when you’re sleeping. Needless to say, I’m missing the whole fact that your unconscious is processing, your brain is resting and your body is recuperating. There’s a lot that’s happening when you’re sleeping. But in my impatience I’m like, Nah, I want to do something. I want to do stuff. I don’t want to retreat to bed. I’ve gotten to this age now, 59, where it’s like there is such a thing as the end of your energy. There’s such a thing as wearing it out entirely. The machine starts to break it down and it ain’t going to recover like it did when I was 30 or 40. So now I think it’s time to cultivate some rituals around rest.

Kiara: Right. I’m just curious, how many hours of sleep would you say you get at night?

Darrell: To be honest?

Kiara: Yeah, to be honest.

Darrell: I would say mostly around six, sometimes less than five. If I do a couple of days of less than six hours of sleep, like I have been the past few days, I start talking to myself and getting a little loopy. I’ve also noticed that I’ll get brain fog and I can’t remember names. The conflict I’ve always had is that I thought that to be an artist it required those kinds of sacrifices. For example, artists can’t sleep or artists don’t eat…they just do the work. They do the work all the time and, you know, that’s romantic. I think it can be true but what they don’t actually talk about is the consequences of that. It’s like: yes, that is true and sometimes if artists do that for too long they get sick and they die just like everybody else who does that. I didn’t really think about that part. I’ve got to change this attitude towards sleep. I’ve actually got to change because I can’t just make myself go to sleep. I always found that when you want to change a habit, you have to care about something else more, and have to find something else to care about more. So I need to find something else to care about more than staying awake.

Kiara: That definitely makes sense. What would be your definition of self-care? If you could form your own definition using the practices that you’re already doing, do you feel aligned with self-care?

Darrell: Oh, man. Now we’re moving into therapy. Okay, Doctor, I’d love to talk to you about this.

Kiara: [Laughs]Sorry, just trying to ask the right questions!

Darrell: That’s a good question. I feel like you got a little Oprah on here. [Laughs]Well actually Kiara, what I really need to do is… My definition of self-care…well… it’s a big question. I feel like self-care can start anywhere. I think the first place I would have to start for myself is being honest with myself. Right. Your body changes as you age and you have different needs. I keep feeling like when I was 20, I could live on ice cream sandwiches and ginger snaps for weeks. I didn’t have to eat food. I didn’t get sick. I didn’t gain weight. When I was 30, I was totally skinny and didn’t have to do anything. As you get older, I think this idea of being honest with yourself about what you need [is] the first thing. Then once I come to terms with that, then I’m faced with the fact about being honest about who I am. That’s the first step to me in self-care, is honesty. It’s funny… I mean, it seems strange to think about the idea of being honest with oneself, because you think, well, if you can’t be honest with yourself, who’s making you lie to yourself, but in some ways that’s the hardest thing, right?

I noticed this in two things in the Will Smith interview. And I also watched a film about Magic Johnson and how he would talk about Magic like it was a third person, His name is Irvin Johnson. So in the film he would say “Irvin was this, but Magic required this.” I just thought to myself, This is so strange. He’s living this external persona. He is a prisoner of this persona that he created. What he thinks the world expects of him and inside him, there’s this kid, that’s Irvin, that was before all the fame happened. It’s funny, Will Smith said the same thing. So I thought, okay…so being honest with oneself in part is like, what am I doing? Because the world thinks that’s who I am, and what am I doing? Because that’s who I think I am and who I really want to be. And I think to myself, that’s the root of self-care because once I can come to terms with that, then I can say, well, what does that person need? What does Darrell need that’s separate from what the world expects me to be doing?

Kiara: That’s a very powerful way to look at it. It makes me think of this concept of the “inner child”, we all have our inner child that we’re trying to nurture and heal. I think that’s also a part of self-care is recognizing your inner child.

Darrell: I’ve heard that idea; t’s been around for a long time. Our parents are always trying to get us to grow up and we’re just trying to be adults or act like an adult, grow up, be mature. Right? How is it that we’re supposed to be paying attention to our inner child when they keep on trying to get us to not be that person and to be a grownup person, you know? I have an appreciation for the authenticity, the individuality, and the joy and all of those things that were inherent in that. I might not call it my inner child. I might call it my real self, you know what I mean? I was closer to that real self in many ways earlier on when I was younger.

Kiara: I think about the action of unlearning and getting back to that essence, like who you are at your core. How do you cultivate sacredness in the spaces you inhabit?

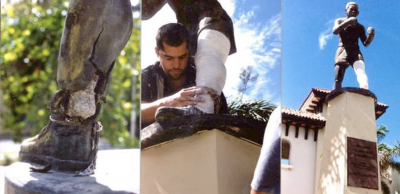

Darrell: Hmm. Another fantastic question. Dr. Walls. Wow. So I’m in the process of activating this space in Northeast Killingsworth that used to be the Albina Arts Center(1) way back in the 1960s. I didn’t know [ the history of the space,] when I walked into the space, but I felt something that was so amazing. I’m not a person who just skips down the street, but I’m telling you when I closed the door and I had the key to that place, I was skipping around inside it. I was thinking to myself, This is not like me. I was talking to somebody about it and they said, “You were feeling the spirits of all the children that had gone through that place in this year.” I would say an element of sacredness is history… knowing and honoring the history of who came before. That is something that I feel, I mean I’m not going to start a religion around it or anything, but it’s so important to me that I would say that it’s a core principle. You have to honor and recognize the history of what came before and those who came before. A lot of the work that I’ve done in my time here at PSU has been this sort of discovery of and uncovering and then trying to represent past history, whether it was the jazz scene on Williams Avenue or the the Black jazz musicians who were, you know, the old cats in the scene way back in the 1950s and 1960s and sort of trying to find a way to see them honored. That’s one of the ways that I try to honor spaces is to know about them and represent their history.

Kiara: That makes me think about Sankofa(2) and looking at your past to inform your future. Learning your own history or learning the history of your ancestors or whatever spaces you’re inhabiting. That’s definitely a way to activate the space and you’re also paying homage and giving them their flowers, you’re recognizing them. I’m super excited about that project too.

Darrell: Thanks. It keeps on growing. I’ll have to send you the list of things that are happening. I didn’t bring my Kwanzaa on Killingsworth postcards.

Kiara: It’s all good. I’ll give you a shout out next week. Where do you see yourself on your healing journey?

Darrell: Hmm. Wow. Where do I see myself on my healing journey? I think I have some degree of self-awareness. I think that I’ve learned some things. I think that I’m fortunate in that I’ve inherited a lot from my parents and my family. My father was the youngest of 12 children. My grandfather was a sharecropper in Arkansas and he worked his whole life to get his family out of the South and move them up North. My dad was the first in his family to go to college. I have a master’s degree and a teaching job. I started with a strong foundation in thinking and a strong moral background. I also believed that I was and could be okay and that I was worthy. There’s a lot that I brought to the table. There’s still a lot for me to learn. I have this idea of being my true self and not being so susceptible to the patterns from my past or from the outside culture sort of running me in a particular direction,that aren’t necessarily in my longterm best interest or that don’t feel authentic to me. I’m happy with that. I’ve done many years of therapy and counseling. I’ve had the privilege of having access to that and taking advantage of those. I’ve also been around some really amazing people who’ve taught me a lot and have been good friends. So in a way I feel like I’m pretty evolved, but I still see all the ways in which I’m like, I’m clueless. I thought I had that together, clearly I’ve got a long way to go, even in terms of attitudes and perceptions. I feel lucky. I feel very fortunate and blessed in my life. But I also feel that I’ve got a lot of work to do. Some days I feel optimistic about doing that work and other days I feel like I’m never going to get it.

Kiara: Thank you for the transparency. There’s this idea that I’ve been thinking about, the yin and yang symbol. You can be on your healing journey feeling really good and at the same time, still have this other stuff that you’re dealing with. Those two experiences can happen at the same time. That doesn’t mean that you’re not evolved or like you’re behind or anything, it just means you have momentum and are moving in the right direction. But realistically you still have these things going on at the same time, which is normal and human. I think a lot about grace.We want things to be all good, all the time, but that’s not how life is, right? In life there’s a balance. There’s definitely a balance. It’s also about the perspective that you have and choosing to focus on the good that you have in your life and not necessarily let the bad outweigh that, you know?

Darrell: Also I think gratitude, you know, being grateful to be…I’m grateful to be on the path. That’s what makes me feel good. I still have the opportunity to learn. And you reminded me that I have this habit of setting an alarm for things that I want to remember on my phone. Most of them don’t go off anymore, but when I’m setting new alarms, I’m scrolling through and seeing them. Some of these have actually been on my phone for many years. I started this habit when I was trying to be a better parent to my son and remind me of stuff that I wanted to stop doing. And so I was just looking at my 8:20AM alarm and it said, “Shut up and listen, stop pushing half faith every day”. My 8:34 alarm says, “Increase my willingness to accept suffering.” And that’s on every day. 8:35 is, “Consider the possibility of not worrying about the future.” 8:45 is, “it’s okay, Darrell, there are others who are well-equipped and well-prepared to do this task. You can focus on your own activities.” 9:45 says, “Can I embrace self-care with intentionality as an act of resistance?” That’s been going on for a good year. 3:00PM: “How do I eliminate the guilt and anxiety of not having things done?” 8:00: “Seek out and delight in opportunities to learn every day.” It’s just reminders to keep staying on the path and checking in.

Kiara: You’re checking in with yourself and I think that’s amazing. I might actually start using that because I love it. I have a coworker that has an alarm set for something, I don’t remember exactly what it said, but it was something very optimistic, like “Keep going,” or “Things aren’t that bad,” or something like that.

Darrell: I mean, if you’re going to have a phone, it’s a good use of your phone.

Kiara: Yeah. I feel like that’s an appropriate use. That’s healthy. We’re onto our last question. What advice would you give to someone who is seeking to heal their past traumas?

Darrell: Well, I think you already said it. I think grace is the thing that you have to keep. You can always come back to it. It’s not like it’s not a continuous linear thing. Just to be able to forgive yourself and give grace to yourself, I think that’s probably the most important thing because you know, it’s an ongoing journey. So I think that’s the thing I would say mostly.

Kiara: Thank you so much, Darrell, I appreciate your voice and your perspective around this topic.

Darrell: Thanks for asking such great questions.

Footnotes:

(1) Albina Arts Center was a “historic art and culture hub that was a touchstone of Portland’s African American history.” It is now a resource center called the Center for Advocacy and Community Involvement, run by the police accountability group Don’t Shoot Portland to assist community members with social equity-related causes. (Portland Tribune, 2020)

(2) Sankofa is a word in the Akan language of Ghana that translates to “go back, look for, and gain wisdom, power and hope.” It implores for Africans to reach back into ancient history for traditions and customs that have been left behind.” (Wikipedia)

Kiara Walls (she/her) is an arts education administrator, originally from LA but now stationed in Portland, Oregon. Her work is centered around increasing awareness of the need and demand for reparations to repair the injuries inflicted on the African American community. This interpretation is seen through many forms, including story-telling, site specific audiovisual installations, and the Black Box Conversation Series, a monthly interview series on Portland State University Radio. http://psusocialpractice.org/kiara-walls/

Darrell Grant (he/him) Since the release of his debut album Black Art, one of the New York Times’s Top Ten Jazz CDs of 1994, Darrell Grant has built an international reputation as a pianist, composer, and educator who channels the power of music to make change. He has performed throughout the U.S., Canada, and Europe in venues ranging from Paris’s La Villa jazz club to the Havana Jazz Festival. Dedicated to themes of hope, community, and place, Grant’s compositions include his 2012, Step by Step: The Ruby Bridges Suite, honoring civil rights icon Ruby Bridges, and The Territory, which explores Oregon’s landscape and history. Since moving to Portland, Oregon he has been named Portland Jazz Hero by the Jazz Journalist Association, awarded a Northwest Regional Emmy and MAP Fund grant, and bestowed the Governor’s Arts Award. He is a Professor of Music at Portland State University where he directs the Artist as Citizen Initiative. https://www.darrellgrant.com/

Process, Pop, and A/Temporality

“Without one another we don’t have the context that makes our sense of self meaningful—to accept distortion and accept mutation is to accept one’s place in the world.”

ALEX OLIVE

Alex Olive, or Olive, is a visual and sound artist based in Oakland, California. I am particularly interested in her experimental sound practice and how she uses and manipulates field recordings. I think that there is something really special in getting to listen to artists talk about their work and their processes, especially artists I admire.

Olive and I spoke about her practice and process, her upcoming album, and what excites her about making music. I’m really interested in starting to make experimental sound art a part of my practice, including the use of field recordings, and I’m really excited about the possibilities that could come out of using sound as material. I’ve been thinking a lot about temporal intimate spaces, both physical and emotional, and I wanted to talk to Olive about how her practice and process explores those concepts.

Alex Olive: So what were we talking about?

Luz Blumenfeld: I started recording because our conversation felt related to something I learned in class this week when I did my presentation on my practice, which is: the way I was previously thinking about documentation in social practice art was really limited. I thought you could take a picture or a video, or show an object that was a part of the work, and that was pretty much it. But everyone in my program was like, No, there’s actually a lot of different ways to document a project. So then I was thinking about how I’ve used voice memos on my phone as a tool for recording for a long time and how I usually don’t have an intention behind that beyond the feeling of, Ooh I need to record this right now. But I have this collection of moments in time, and I was thinking about what you were saying about the beginning of recorded music aiming to just capture that moment.

Olive: The history of pop music or popular music as a specific form is really interesting to me. The way that it’s developed has been sort of like, inseparable from economic relations and from social relations, like interpersonal relations. The beginning of pop music, I mean, in a certain way is like Tin Pan Alley type shit where it’s like, people were just banging out sheet music for songs every single day. Just like creating endless amounts of songs for people to take home and perform for one another.

Luz: That’s really cute.

Olive: Yeah, and like, for the longest time, reproduced and manufactured music was like, you know, sheet music that people would play in their parlor to entertain their guests or their family, and so people were cranking out tunes every single day for people to go home and play. But then after a certain point that stopped being the relation of like, one of us is going to perform something for a group of people, to someone in another part of the world has performed something outside in a field or in a room specifically designed for this. And then we can listen to the fact that somebody has played music.

Luz: That’s honestly really cool as a concept. Just the fact that we can listen to someone play music in a field far away.

Olive: Yeah. It’s far away in space and also in time, moreso all the time.

After a certain point, technology and technique sort of made it even further divorced from the original moment of performance or the original moment that is being documented, where you have overdub technology where you record one part and then play another part over it. And so what ends up being recorded is not one performance of a song, but like a curated selection of various people performing it at completely different times. And then you get mixing, which makes it even more complex, and then sampling and using Mellotrons and other instruments.

Luz: What’s a Mellotron?

Olive: Oh, it’s like a keyboard instrument. It looks like a piano, but it’s loaded with tape loops inside of it of different instruments playing a single note so that you can switch it to something like a violin or a flute. And then when you hit the keys, it plays basically a tape of a flute playing those corresponding notes.

Luz: That’s like my childhood memory of what a keyboard would do. Not a piano, but like a keyboard.

Olive: Yeah, totally. That is extremely similar to how the MIDI [Musical Instrument Digital Interface] works now, where you can just put in… I mean, maybe it’s a bit more similar to a player piano where you can just put the notes that are supposed to be played and then you just plug it into whatever instrument or thing is supposed to interpret that.

Luz: Player pianos are fascinating to me because they’re really similar to early looms.

Olive: Yeah, because they’re similarly, like, computerized sort of.

Luz: Yeah, well they relied on this punch card system with holes in different places and the same is true with the player piano. I used to have a sheet of player piano music that I got for free at somewhere like the Depot(1) at some point and I just hung it on my wall because I thought the pattern was pretty. It was just a really thin sheet of paper that had a pattern of holes in different places.

Olive: That’s really, really fucking cool. But yeah, I think the way that I use the MIDI is very similar to a Mellotron. I typically sample either like found sound shit or a lot of times, well, not even just me, but a lot of people use sound fonts. They’re most commonly associated with, like, video game soundtracks. With sound fonts, you can download all of the instruments that were used to make a specific game soundtrack, and then you can use them as your own, basically. And I’ve only really recently started using sound fonts but they definitely help with what I’m trying to do in terms of like, melodic sensibility and maybe even just like, emotional presence. Video game music has been hugely influential in how I approach music, in part because it’s supposed to create an environment. You’re supposed to go into a level, area, or environment and then the specific loop of music is supposed to be playing indefinitely.

Luz: And it has to feel different from whatever space you were in before, but also still on the same theme so that you’re still in the same world.

Olive: Yeah, it’s like score music, but also looped, which I think is interesting because if it’s looped indefinitely and specifically connected to a place, that implies that the passage of time in the piece of music doesn’t matter because it just goes on forever, which means that it ceases being a composition unfolding across time and becomes in itself a sort of place-state or like, an aspect of place that also isn’t real at all.

I grew up playing video games a lot and my immersion in them was to the extent that I remember having to write a “What I Did for Summer Vacation” paper in the third grade and just writing about playing Pokemon but as though it was real, essentially because all I had done that summer was beat Pokemon Gold.

And, I don’t know, for some reason synthetic and artificial spaces were way more close and emotionally accessible, and real to me as a kid [more] than anything that was happening in my physical life. And I think that I’ve only really been able to appreciate the real world through my relationship to synthetic worlds. And I think that’s kind of part of why I use a lot of like, sound font type shit.

Luz: That’s really cool, that makes sense.

Olive: Yeah, and a lot of my music, even though it changes composition and the arrangement sounds really different at one point in the song than it would in another point in the song, I attempt to use the same chord progressions with the same few pieces to sort of like, imply a similar place-likeness where it’s just one thing looping for a really long time. But what you’re getting is these different layers and different interpretations of what that is or could have been.

That being said, there is a certain school of thought against world-building in art that I do more and more sort of agree with.

Luz: What is that?

Olive: Basically I think the sentiment is that when our attempts to be a world-building thing beyond the scope of its medium, like, I don’t know. You see this all the time where people put out albums and they’re like, “It’s not just an album, it’s a whole world,” you know? Or like, you have an ARG [Alternate Reality Game] experience to promote the thing or there’s the implication that engaging with this piece of art is somehow going to, like, transcend the boundaries of real life.

Luz: Yeah, it reminds me of— and I didn’t actually watch this, I just saw it get memed a bunch– but like Mark Zuckerberg announcing the metaverse thing, like it feels like that.

Olive: Yeah, it feels very similar. And there’s also, like, the theme park-ification of museums and shit.

Luz: Oh yeah, that’s a whole other thing I could talk about for so long.

Olive: Yeah and I think that also what frustrates me about world-building or like, obviously world-building is part of the narrative arts if you’re doing fiction or even non-fiction, but like, in terms of making a piece of art and saying, “This is a total experience, a total work of art,” I think is dishonest and undesirable, because nothing is total, art is necessarily inseparable from the context in which it was made. And to say that it’s its own thing that transcends the boundary of experience is, I think, really silly and also just disengages from what is important about the arts.

Luz: Yeah, it feels like a marketing technique and like a promise to be better than something else, and that feels weird to me in an art context because it feels really far away from the thing that made you excited to make that work. I think it’s cool when that’s still somewhat visible.

It doesn’t have to be the entire thing, but you can still have traces of why you made this and what was interesting about it. To attempt to make something entirely divorced from the context of its creation feels silly to me.

Olive: Yeah cause also it’s like, if you feel the music or painting or whatever has the capacity to communicate something in excess of what it is—which is true, that is how art works, that is how perception works, then isn’t that the value of the medium and the value of the work you’re making? And isn’t it sort of insisting that that be like, totalized into a whole other like, separate world sort of insisting that art is primarily a form of escapism? Which is a notion that I try to rail against really hard, even though I’m making pop music.

When I do stuff that is really similar to video game soundtracks and more specifically, JRPG [Japanese Role-Playing Games] soundtracks in my work, I try to do it through a lens of it being distorted or feeling half remembered or buried under processing of some kind, so that it feels untrue and inaccessible, but also like, a nice memory, a nice thought.

Luz: I’m interested in the untrue and inaccessible part.

Olive: Yeah, I don’t want my art to be interpreted as just like, Wow, this reminds me of when I was a kid playing video games, it’s so awesome to be a child! I want it to be like, your emotions are still real, your memories are still as happy as you can imagine, but also your memories of childhood have been scrubbed of all context, they’re completely divorced from the reality of that— especially idealized ones about how awesome it was.

Luz: Yeah, or like the stuff that makes you weirdly nostalgic, and you’re like, I hated being that age, but when I hear this particular soundtrack for this thing, I feel like I’m just blissed out about it. Weird.

Olive: Yeah, and I think there’s a sort of cultural precedent to be like, Oh, well this made me feel safe as a kid, which is, I think, very valuable to be like, This is something that meant alot to me during a difficult time. But even still, at some point, there’s life outside of your best memory, there’s endless potential for the world to be happy.

This goes along with the theme of anti-escapism pop art shit, but my favorite, I think, work of art ever is fucking ‘Neon Genesis Evangelion’, and one of the big takeaways from that as stated in the movie ‘The End of Evangelion’ is–I think the line is like, “Anywhere can be heaven as long as you choose to live.” And I think that is very true. Basically I think the broader implication of that is that the world we live in and are materially a part of— that we have to make choices to be a part of— is the only place that we can access happiness and intimacy and all of the things that make life beautiful, but it is also necessarily a place where all of the pain you will ever feel exists as well. And so, if you really truly believe in accessing the beauty that you felt as a kid, or the things that made you feel safe, then you have to accept that you are a part of a world that is also not very simple and you have to do right by the positive emotions and continue living in the world.

Luz: Yeah, I think the part that I appreciate about what you were saying, what you’re trying to do with your music– I feel like I’m getting better at describing this because for a long time I wasn’t super into music, like, you know, I had songs and artists that I liked for some reason, but I didn’t—having no understanding of how music is produced or anything, I think, changes the way you hear things a lot.

Olive: Oh, absolutely.

Luz: And having any sort of artistic, medium-specific connection to it really changes the way you experience it. But yeah, I think something I really like is when I can pick out different sounds within a track. There will be something that reminds me of something else, but it’s not the whole thing. I guess that’s what intrigues me about using field recordings and stuff is that you can kind of pop it in for a little bit, but then it goes away and other things keep happening, and I like the way that makes you experience time.

Olive: Yeah, totally, because that means that the recording of the initial thing is edited and is inserted in a way where it makes you aware that it’s edited and it makes you aware that it’s like a memory, as opposed to a total experience.

Luz: Maybe it’s because I’ve recorded so many voice memos over the years, but whenever I can pick out a field recording in something that I’m listening to, it does feel like a memory, but not my memory. I think that it’s the person who recorded or, I mean, I guess people use other recordings that they didn’t make themselves, but in my head I kind of imagine that it’s the artist who has this, you know—I’m thinking of that Grouper track with the owls field recording.

Olive: Oh yeah, I’m certain that was probably done by her.

Luz: Yeah, so then I think it’s cool to get to feel the complexity of someone else’s memory of that experience and then the memory of recording that and then all those layers and just hearing the one sound is really exciting to me.

Olive: Yeah, totally. It reminds me a bit of Caveh Zahedi’s whole theory of film being like capturing God essentially; where you’re capturing the sort of unfolding of an embodied moment in a certain way, and that, in so doing, you’re capturing the essence of the divine because the divine permeates all things and unfolds across time, so if you are recording time, you are sort of making a recording of like, the face of God essentially. And that’s a very broad paraphrasing of Caveh Zahedi, but that’s kind of generally what I seem to be getting from his work. But yeah, I think using field recordings and found sound is increasingly something that I want to do. Something else that I am thinking a lot more about is improvisation in music and irreplicability and wanting to make things that, even if they are recorded, they may not be replicable in the sense that they are completely improvised. And I think noise music and other types of experimental music are pretty ready to be used to that end, and that’s definitely something that I want to push harder in future projects.

Luz: Yeah, that interests me a lot too, and I think a lot about––especially in regards to social practice art–– what it means for something to only exist in this one time and place. I mean, if you record it, you have that documentation of it, but it’s removed and it’s different and it’s not the same as having that experience of being in that space at that particular time. And I like that, I like the idea of doing that and not recording it and it only living on as documented in people’s memories.

Olive: Yeah, I mean, I think in some ways that may even be preferable to something like a video recording just in the sense of something like a video recording does give you the illusion that you’re experiencing it as closely as you could be, but aspects of actual presence and embodiment and the affect and the sequence of the unfolding of the thing and how that makes you feel as an immediate observer in the place, in that specific time, are intangible and unreportable.

Luz: Yeah, and unrepeatable.

Olive: Yeah, exactly.

Luz: Two things I’ve been thinking about in connection to that is: one is that rave we went to last week and all the intention behind it. I would honestly love to talk to the people who organized that about what they had in mind for what they wanted it to feel like for everyone there, and maybe talk to other people who were there about what it felt like for them.

And the other thing is, I was talking to Alex [a mutual friend] yesterday about a memory of a very specific part of Telegraph Avenue [in Berkeley, CA] and I remembered I had a picture of myself in that exact spot when I was like, 15, so I tried to find it. I went through my external hard drive and instead of finding that, I found an entire folder of photos and videos from a Nikon Coolpix camera of Live105’s BFD(2). The videos— it’s like me shaking in the crowd and you can hear me singing along and it’s very weird to hear your teenage voice, but I was thinking about what my intention was when I was recording that as a teenager. I think I wanted to remember it, but I probably never looked at the footage until I found it just now.

Olive: That’s crazy.

Luz: Yeah, but I feel like there’s something interesting there about recording performances and I guess feeling this compulsion to record and you don’t really think about why. I’m thinking about that in connection with intentionally not recording something and having it exist as a one-time event, but also it lives on in people’s memories and the conversations they have and the way it informs their practices and whatever they end up doing too, which is also really cool.

Olive: Yeah, totally. I also have been told about things— pieces of art and stuff that are so amazing when people are telling me about it, and then when I experienced it for myself, I mean, it’s probably still pretty good but it doesn’t have the charm of my friend’s interpretation of it.

Luz: Yeah, I also feel like there’s so many works that I’ve heard people talk about that I’m like, “Oh shit, I love what you got from that,” and I don’t end up ever looking at the actual thing they referenced because maybe it doesn’t exist anymore or whatever.

Luz: There are certain parts of your album you have shared with me that incorporate field recordings. You’ve told me where some of those field recordings originated and I wonder about the intention to use those specific sounds even though someone may not be able to pick them out and be like, Oh that’s what that is. Why use those sounds? And what does it mean to not be able to recognize them?

Olive: I think there are a few moments on the album where I use field recordings that are very legible and people can pick up what they are, but I think for the most part that’s not the case and I think that my thought there is that it’s all memory. The way that I feel about consciousness or the soul is that it is essentially an experience of memory, but not as a linear, sequential thing of like, This is everything I’ve experienced in my life, but as specific moments, one at a time, that themselves contain an entire network of everything you’ve ever experienced. So my thought is that by using processed, prerecorded, materials, it’s a similarly endless jumble of half-remembered, distorted, or idealized memory sort of fighting for a place in one’s experience of any given moment.

And there are points at which that becomes more part of a theoretical arc of the album—it does start out as a more idealized and cogent conception of identity that should be defended by self-actualization, and then, after a certain point, flips to being about that distortion of memory and the distortion of even the notion of a static identity of sense of self. And that, that is actually in and of itself possibly more empowering than saying, “I am this one way forever and you all have to fuck off,” because I think that intimacy and connection with people, connection with the world around you, is inherently sort of mutative. It’s only through connection and presence that you can really access what it is to be alive, which in turn requires relinquishing control of the possibilities of who you are and what your life can be. This is the connection we have to offer each other and that can be beautiful. Without one another we don’t have the context that makes our sense of self meaningful—to accept distortion and accept mutation is to accept one’s place in the world.

Luz: I love that. Do you want to tell me more about your album?

Olive: My album is called Here Are My Tears of Joy, and it is basically half an experimental pop record and half a more broadly experimental record. I feel a little bit as though this is the last thing that I wanted to make, in the way I’ve approached it for the specific reasons where it has a sort of emotional arc to it and it has things that it’s trying to do formally and communicate lyrically that I think were born out of an experience of art and music that was about listening to things in headphones alone and trying to really divine meaning and communication from other people’s work and wanting to do that the same way that I no longer really have a lot of faith or stock in. But I think that, it’s in the form of a pop album and so that’s like, the idiom that I’m working in: communicative songwriting and attempts at communicated abstraction.

The album is a lot about the stuff I was talking about a second ago in regards to self and identity, but I really think I should preface any discussion of my art being about the self or about identity by saying that, even though I’m transgender, my work is not about being transgender. (laughs)

Luz: (laughs) Isn’t everything about being transgender?

Olive: Yeah, everything is about being transgender. Everything that is about being transgender should only be about how fucking awesome identity is and how important and supreme it is over all other types of experience or discourse (laughs).