The Tapes, Conversation I

December 12, 2021

Text by Rebecca Copper with Marti Clemmons and Gilah Tenenbaum

“…There was that fear: What if I don’t have full parental rights, just because I’m not the biological mother?’”

MARTI CLEMMONS

Public Domain image by Renee Comet acquired from National Cancer Institute.

Tomatoes, with little tomato seeds, and tomato flesh dripping with tomato juice. Growing up, my grandmother and my mother were always exchanging tomatoes. Tomatoes that they either grew, or found at local farmer’s markets. They would give these tomatoes to family members, friends, co-workers, and each other. Although, the conversation you’re about to read has nothing to do with tomatoes. The conversation you’re about to read has everything to do with closed objects, restricted audio tapes(1), lesbian mothers, and custody trials during the 1980s. In the 1980s, my grandmother left her second husband to live alone in her own home, after her children had grown. In the 1980s, my mother graduated from high school, studied medical assisting and married my father. She also gave birth to my brother and then to me. My mother would later divorce my father in the 1990s, the same time she began working nights for the United States Postal Service.

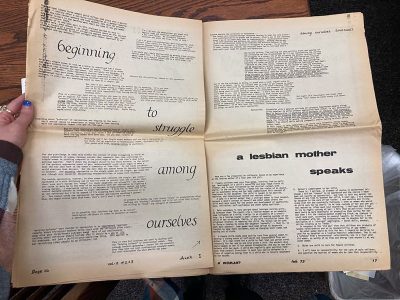

About a month ago, Marti Clemmons [an archivist, now friend and collaborator, who I met through my research assistant position with Portland State University’s Art and Social Practice Archive] shared with me a collection of restricted audio tapes. I wasn’t able to listen to them, but I was able to look at them in a box. These audio tapes were given to Portland State University’s archive from the feminist bookstore, In Other Words, after it closed a few years ago.(2) The tapes contained personal accounts of lesbian mothers in the midst of custody trials during the early 1980s. Their husbands or ex-husbands didn’t want the women to have custody of their children because of their sexual orientation.

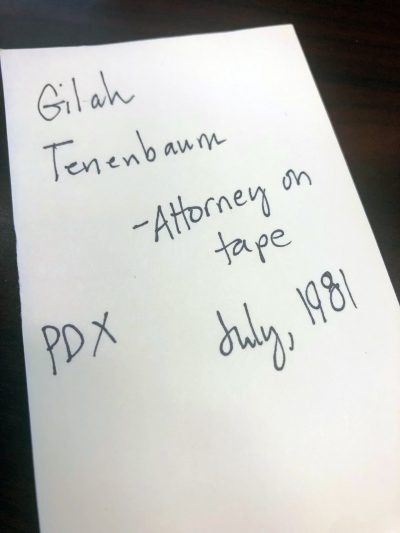

Having history as a single mom, who has had my own experience with lawyers, guardian ad litems, counselors, and such, I’ve developed a personal interest in post-separation abuse, coupled with the use of family court as a tool for abuse. Marti, being a queer single parent, has their own immense connection to the tapes. I told Marti that I would do whatever I could to help find the women on these tapes— to ask for permission to share their stories. We ended up locating a Gilah Tenenbaum. Gilah is a retired lawyer who was recorded on one of the tapes. Gilah doesn’t have children, but was active during the time of these trials and very much a part of the lesbian community in Multnomah County, Oregon. I reached out to Gilah and asked if she knew anything about the audio tapes. Maybe she could help Marti and I locate the people on the tapes so that we could get their permission to share these recorded stories. Marti had digitized the audio tape that Gilah was on.(3) We planned to meet with Gilah over Zoom while Marti was at the university’s archives so we could have her listen to the recording. Unfortunately, at the time of the meeting— as it goes with the life of parents— Marti was stuck at home caring for a sick child, so we weren’t able to listen to the recording. The closedness of the tapes, the remaining lack of access to the actual content of the tapes, adds more power to them.(4) And, consequently, for me, added more meaning to our dialogue about them. My hope is to document a succession of conversations in relation to these tapes from In Other Words, as we move through the process of searching for the people who are recorded on them. The following is the conversation of our first meeting, between the three of us: (Marti, Gilah, and myself).

Rebecca Copper: Marti, if you don’t mind going over some of the things you do and maybe give some context for these tapes, that might be a good introduction.

Marti Clemmons: Yeah, I work in the Special Collections and University Archives at Portland State University. I’ve been there for nearly 12 years, off and on. Now, full-time as an Archives Technician. I process a lot of the collections: I look through things, I throw away the things that don’t have significant historical context. I get collections ready for the researcher, or the user— patrons, students. We acquired a collection a few years ago from In Other Words, a feminist bookstore and collective. They were located in Northeast Portland. I think it was about five boxes. One of these boxes, it was offset, was a collection of about 70 cassette tapes. The custody tapes were of mothers who came out in ‘81— well, probably came out before that, but a lot of the tapes are labeled from 1981, 1982, and 1983— mothers that came out to their husbands, and therefore, their husbands took them to court for custody of their children. So, lesbian custody tapes, I guess is a broader way to describe them. I’ve only been able to listen to a few of them, they aren’t digitized. The only information on the tapes is a name and a date, sometimes initials. There’s no release forms. There’s nothing else.

Gilah Tenenbaum: Is there a name of an interviewer or an interviewee?

Marti: Usually, it’s just the interviewee. A lot of the time on the cassette tape, it might just have initials. I’ve noticed a few that have the same initials. Some of these tapes also take place in Los Angeles. I don’t know what that connection is, either. In an oral tradition or practice, the interviewer would state their name, who they’re interviewing, place, date and so on. I haven’t been able to listen to all these tapes, so some might say the names as they’re introducing. I know on your recording, specifically, it gets cut off, the interviewer’s name gets cut off.

I don’t think Rebecca told you yet— I think I recognize the other voice, the interviewer, which is even stranger. I took an oral history capstone class, from a person named Pat Young, who is a historian in Portland [Oregon]. I swear it’s her voice, but I haven’t made that confirmation. She has a very specific laugh, and it would make sense that she would be doing these tapes. I know that she did have some connection with, I think, Katharine Williams, who’s also mentioned on the tape.

Rebecca: Gilah, there is a Katharine that you mentioned. You said I should reach out to Katharine English. Is that right?

Gilah: She was one of the first, if not the first attorney, to win a lesbian custody case in Multnomah County. She educated the judges, she really put in a lot of effort. It came to be that you could go to court in Multnomah County, and you weren’t going to lose just because you were a lesbian. This was a long time ago, but I think the circuit court generally, in Multnomah County, not just this one judge, came around to deal with these cases the same way, whether or not they personally approved.

Marti: I’ve listened to bits and pieces of your interview and I’m sorry that I’m not at work, I had planned to share a snippet with you— but, you do mention different judges, and just the way that it works. How you would walk in, almost having to expect to lose. I feel like these women, you know, with every inch of their being, they wanted to fight for the custody of their kids. Going into court, it’s traumatizing and scary. And, on this recording, you had a lot to say about that and the different judges, not necessarily by name, but what to expect.

Rebecca: Marti is at home with a sick child. That’s why we can’t share the tape you’re on, we totally planned to have audio for you to hear.

Gilah: I was looking forward to it.

Rebecca: It’ll happen, though. I’m sure we’ll get it to happen at some point.

Marti: The recording is about an hour and fifteen minutes, it’s a long conversation. The snippets of the other tapes that I’ve listened to, it’s devastating. It’s their life stories and what they’re trying to accomplish while going through court. It’s really nice to have your tape. Not as someone who is going through a custody battle, but someone who has a different, outside perspective. I think you say on the tape that you were also community support during this time, so it was affecting you as well.

Rebecca: Gilah, you were just talking about how you weren’t sure how much insight you’d be able to give, considering that you weren’t a mom going through one of these cases. But you were a lawyer, you were a lesbian, and part of the communty. Because I’ve been through court custody-processes myself, when Marti showed me these tapes I was interested in the conversation about family court used as a form of abuse or control. So, there’s that way that I connect to the tapes. I wasn’t born until 1989. I wasn’t even alive when these tapes were recorded. But, you were the name Marti had. Then, I tracked you down. And you were there, you were physically there. To me, it’s valuable how the three of us are connected to these tapes. Also, how some of what was happening in 1981, is essentially, in some ways, still happening today.

Gilah: Oh, yeah.

Rebecca: I was hoping that maybe we could connect in a dialogue over that and maybe some of your experiences. I don’t have any prepared questions.

Gilah: I’m happy to help in any way I can, given all the caveats, you know. I have a vague memory– really vague. Maybe I even created the memory once we started talking; that I was once involved in something with interviews, but you know, I don’t remember a whole lot.

Rebecca: What do you remember?

Gilah: Just that it happened. Not any specific incident. I’m trying to think if I was in a conversation with Pat Young. Was she in a position of having to go through this? Or, were she and I talking as people who were providing support?

Marti: She was in the position… I’m going to pull up my email… Actually I think it is Katharine English, not Williams, now that I’m thinking about it. Let me just pull this up really quick. There are records that say that Pat was working with and doing this type of oral history interviews during that time.

Gilah: And she spoke about Katharine English?

Marti: I’m going to pull my email up, really quick. I remember asking Pat about this a couple years ago. She didn’t say whether she remembers or not, she deferred the question. I am trying to pull that email, I have to scroll because it was a couple of years ago. [laughter]

Gilah: While you’re doing that, Rebecca, how did you find me? It shouldn’t have been hard.

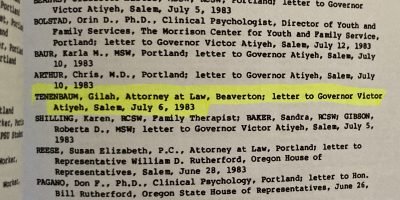

Rebecca: Um, yeah, no. It took me maybe a few hours on the internet. I learned, weirdly, quite a bit by googling your name. Actually, I forgot about this really cool thing I wanted to share with you. I got this booklet titled, Divorce. I printed it out through Google Books, which I didn’t know you could do, but it’s a collection of court documents and articles on divorce and its impact on children. There was a committee held in Washington, DC by the House of Representatives on June 19th, 1986.

Gilah: Is it a collection of essays?

Rebecca: It’s like court documents. But, your name is in this, you submitted a letter to a representative opposing joint custody. I have it highlighted somewhere. It was wild to find this and then be able to print it in a book; to learn there was a committee the House of Representatives created to discuss this topic in Washington D.C in 1986. As I was searching for you, I found that. I was led to your contact information through the Women’s Lawyer Group of Oregon. They connected me to the Oregon State Bar who gave me your email and your telephone number.

Marti: Nice.

Gilah: I tried to look up Katharine English through the Oregon State Bar. I didn’t know if there was a section for retired or inactive members. I resigned from the bar after I had been retired for I don’t know, three or four years— it just didn’t really make any sense to keep paying that money and I wasn’t practicing. I thought maybe I could find Katharine for you through them. But, I wasn’t able to. I don’t remember if Cindy Barrett was involved, but she’s an attorney. She’s now inactive. She certainly would have known what was going on and might have been involved at the time.

Marti: There was a Cindy in this email I’m looking for, Cindy Comfer.(5)

Gilah: Oh, Cindy Comfer! Oh, sure! I haven’t seen her in years. Yeah, Cindy probably worked on cases, maybe even with Katharine.

Marti: I found the email. Pat said, “I will forward your email to Cindy Comfer, who was a lawyer, retired now and did many custody cases along with Katharine English.”

Gilah: So, my memory is reasonably still there! [laughter]

Marti: Cindy wrote me back. This is from 2019. “I’m sorry, but I don’t know anything about these tapes. I remember Joanna from In Other Words. I did some lesbian custody work in the latter 1970s in the 1980s. But, I don’t know anything about these tapes.”

Gilah: Joanna? Did she give a last name?

Marti: Brenner? Yeah, she’s the one that started In Other Words and was active as a professor. I think she may have even started the Women Gender Sexuality Studies Department at Portland State [University]. But, that was the last time I looked into this. I was like, “Okay, you don’t remember.” And, I had so many other things to do in the archives. I got really excited… but…

Gilah: It’s possible that she knows how to contact Katharine English. She might be one of the last people that has kept up with Katharine. All I remember is that Katharine moved back to Utah. She was from Utah, originally. I think she was from a Mormon family. I don’t think she had anything to do with them. I don’t think they accepted her.

Rebecca: What was it like in the ‘80s, as a witness to lesbian mothers going through custody battles? I mean, would you be willing to share what that was like? No pressure by any means.

Gilah: I have a few memories I can share, not tied to specific women. These cases didn’t always come up in the context of a divorce. For example, I remember that there were women who specifically did not live with their partners, to try and keep it from the ex-husband. I remember there was a case one time where the woman got custody, but a condition was that her lover couldn’t live with her and wasn’t really allowed contact with her children. I don’t know if it was in the early 80s or the late 70s, I graduated law school in ’78. I remember that we heard stories all the time about women around the country who were losing their children, so we sent money. Those of us that could help pay for lawyers. It was just crazy. You know, just misogynist, homophobia.

Marti: Did you have that same experience, Rebecca? Well, I mean, you don’t have to go into detail. Did you deal with a lot of misogyny in court?

Rebecca: (6)

Gilah: I would highly recommend that documentary that I told you about, Nuclear Family. It shows a lot of what went on. I remembered when I was watching it, that the women couldn’t be married at the time. It was before there was any legalized gay marriage. That the non-biological mother was not allowed to have anything to do with these discussions. She couldn’t even go into the courtroom. She couldn’t be there for support for her partner. She was just left out as if she didn’t count, which is the same thing that often happened and probably still does. Like, when somebody dies, and their “blood” family comes along and says, “Well, I don’t care if you lived with them for 25 years…” and just completely excludes the partner from any kind of closure rights, whether property or whatever.

Marti: Yeah, when my eldest was born, she’s seven now, there was that fear, What if I don’t have full parental rights, just because I’m not the biological mother? Times are different [now]. Hearing this is just like— that could have been me, 20 years, 40 years ago. I ended up adopting my kids. That’s how I have full parental rights. There are ways around it now.

Rebecca: Even though federally, gay marriage is legalized, there’s still a lot of shit– excuse my language– happening in terms of rights. I’m thinking about conservative states and how much bias can play into a judge ruling.

Gilah: There was at least one time that I remember where a woman moved from somewhere else in Oregon, to Multnomah County. So, when things went to court, it would be in Multnomah County because things were clearly better here.

Marti: I mean, I’m sure that there were cases like that, with people moving elsewhere to get a fair trial, or something close to a fair trial. Yeah, you mentioned [in the recording] that people actually did do that. Wow.

Rebecca: Yeah, that’s a lot. I’m in Ohio, currently, because I can’t pick up my kid and move without money to pay for a lawyer, court fees, etc. And, even then it’s not guaranteed that the judge would rule in my favor. I would have to go through the process; start a motion to move elsewhere and prove that it would be in my son’s best interest. With moving elsewhere to get a fair trial, to even do that is difficult in and of itself. Which makes me think of mutual aid and support. It seems that there is a resurgence in that kind of community-based support.

Gilah: Just from the little that I’ve seen, it is coming back, the sense of a lesbian community is coming back around. Things have changed so much with the greater acceptance of people being gay or trans, however they identify. It’s on people’s minds more than it was in the past. I mean, with the whole craziness that’s going on with abortion, there are national, regional, and local groups that are raising money to help women pay for abortions. I don’t know if there was anything like that back then. I remember giving money, but the money was just funneled through the woman or through her attorney. I don’t remember there being any, or I didn’t know of [any]organizations that were specifically for that purpose.

Something I mentioned in our last email exchange is the Community Law Project. I’ve been trying to remember where it is, this yellowing copy of a 50 page book that was titled something like, Know Your Rights. It had chapters written by different attorneys, and I wrote something in it. [Laughter] I don’t remember what, but I know I have it. I saw it when I was cleaning out some stuff not long ago. There might be something of interest to you there. So I will keep looking for it.

Rebecca: Oh, cool! Thank you! Did the bookstore, In Other Words, close down recently? Like a couple years ago?

Gilah: Yeah. 2018, maybe ‘19?

Rebecca: Do either of you know why it closed down? Was it financial?

Gilah: I remember there being fundraisers more than once, to help keep it going. I think it was just not enough financial support from the community. I was trying to remember where the store was before it was on Killingsworth.

Marti: I think it was on Hawthorne?

Gilah: I didn’t go in there a lot when it was on Killingsworth [Avenue]. I did once in a while. I donated books to them and money; it was also a meeting space, and a safe space for people. I think [the reason] was just basically money, though.

Rebecca: Would you mind telling me a little more about In Other Words? I’ve actually never been there.

Marti: Yeah, it was in the Hawthorne District, originally. I only went into the Killingsworth location. It was small, you walk in, there’s a huge open area, like a gathering spot, lots of readings, lots of music, a lending library. It just felt like a safe space. I moved here from New York, where I went to Bluestockings Bookstore. It was nice to have the same type of vibe, energy and events to get connected, having moved here to Portland and not knowing anyone in the queer community, and going there and just being one with my people. I would always go there because there was a little music venue next door. If you didn’t like the band that was playing, you would just go to In Other Words and hang out. Yeah, I think it was just about the vibe and having a space that felt good.

Gilah: There was a place— I moved here in ’75, for the gay community— it was Mountain Moving Cafe. It was a cafe open for all, but it was known especially as a safe space for gays and lesbians. That closed and that was a real loss.

Marti: Yeah, I’ve come across that name many times in multiple archives. It’s like one of those places, where you think, Ahh, why can’t I time travel? That place just seemed so cool.

Gilah: It was.

Marti: There’s also the aspect with Portlandia, the show that filmed in In Other Words. I know that started off as a good connection, but it ruptured as they kept filming. There with little to no monetary support. And [the show] kind of made fun of, you know, us in the community. That left a bad taste.

Rebecca: Gilah, I was wondering about your position as a lawyer in all of it. With your expertise as a lawyer, in a courtroom, watching as women went through such a process, and understanding the biases of the judges. I’m curious, was there anything that stood out as unconstitutional, or unlawful, for example, that you saw or that you can remember?

Gilah: I don’t remember there being anything unconstitutional. I think there was a lot of white male privilege, assumptions and ignorance about anything to do with gender or sexuality issues.

Rebecca: What would be their [the judges and opposing lawyers’] reason to prevent a gay woman from having custody of her children?

Gilah: Well, that homosexuality was a sin, and illegal in some contexts. They didn’t want the children to be influenced by this. Also that children need a mother and a father. If the children saw two women being affectionate or holding hands, it was not good for the children. The standard is always, What is in the best interest of the children? Under that rubric, lawyers can argue whatever they want, and as you pointed out earlier, they would tear women apart. “Did you have a shoplifting conviction when you were 16?” I mean, so, what?! They would pull out anything they could. “How many times have you moved in the last five years?” Or, whatever, really. I can’t say there was anything really “unconstitutional” other than white male interpretation of the Constitution. You know, all “men” are created equal.

I did some domestic relations. Most of the cases that I handled were settled out of court. And, I did some writing on the way you protected yourself, as a gay person— as a gay person with a partner, or without a partner for that matter, In those days you had to have lots of documents. You had contracts between you and your partner about what would happen if one of you died. Because you couldn’t be married, you couldn’t get any of those assumptions or benefits. I helped people come up with living-together agreements. Like, wills and other contracts or documents to protect their rights, vis-a-vis each other: What’s going to happen if we break up? I was the one that had the money for the down payment. Yeah, but I was the one that was bringing in the monthly income. My theory was always, yes, it’s unpleasant to put one of these agreements together, but it’s going to force you to confront your issues, and to resolve them while you’re still totally in love with each other. That’s the kind of legal stuff that I was mostly doing during that time.

Rebecca: (7)

Gilah: I think I just remembered a judge’s name that Katherine worked on. I think it was Harlow, H-A-R-L-O-W, Lennon, L-E-N-N-O N. I’m going to double check that on my computer to see if he’s who I’m remembering. I would hate to be giving you the totally wrong name just because I happen to remember one of the judges.

Marti: Yeah, I really appreciate that. I feel like I remember you saying that name in the recording. I want to do this again, when I’m at my desk. I really do. I need to figure out if it’s Pat Young, first of all. Then, go forward with that. I don’t want to play something that no one has given permission to play.

Rebecca: Gilah, originally I was thinking we could give you a list of names to see if you recognized anyone, but we can’t actually provide a list. The archive can’t even give out names without signed release forms. Is there a way to work backwards? Like, if you think anyone you know could be on the tapes, could we check that name against the list from the tapes?

Marti: Unfortunately, that’s where we’re at, that’s the only way. [laughter]

Rebecca: I know you said you might recognize some of the names, if you saw them?

Gilah: Yeah. Oh, I might well recognize a name, but that’s not the same as coming up with it on my own. [laughter]

Marti: No pressure! [laughter]

Rebecca: [laughter]

Gilah: Offhand, I can’t think of any friends or even acquaintances who went through that. I think Katharine English had. Other than her, nobody comes to mind. It’s interesting. Katharine, physically, is a very small woman. I don’t think she’s more than five feet tall, but she’s feisty as the day is long. Articulate, and so on. I’m sure she had things to fight just because she was small in stature. It’s hard enough to get taken seriously as a woman.

Rebecca: Yeah, and I really appreciate that name, Katharine English. I’ll make sure to work with Marti, to see if we can locate her.

Marti: Yeah, and Cindy Comfer. I have a connection with that, too. I’ll shoot Pat and Cindy an email.

Rebecca: It’s 7:32pm [EST]. I know, Marti, you have to go?

Marti: Yeah, to pick up the other kid.

Rebecca: I hope Ansel feels better.

Marti: You know how it goes. [laughter] Gilah, it was nice to meet you.

Gilah: Likewise.

Marti: Let’s chat again soon.

Footnotes:

(1) The audio tapes are restricted because there are no signed consent or release forms on record.

(2) In Other Words was a Portland Oregon feminist community center and bookstore and was featured in several episodes of the Netflix comedy series, Portlandia.

(3) Due to the age of the tapes, they are digitized to prevent further wear and tear on the tapes from being listened to repeatedly.

(4) In a conversation with artist Lucia Monge, Lucia pointed out the power of a closed object.

(5) Mentioned in an email from Pat Young to Marti Clemmons as someone who may be connected with the tapes

(6) Redacted text

(7) Redacted text

Rebecca Copper (she/her) is currently a graduate candidate at Portland State University, through the Art + Social Practice MFA Program, where she worked in 2020 as a research assistant for Portland State University’s Art + Social Practice Archive. Rebecca’s work centers on ontology; how our being and perceptions of reality exist against one another. And, how that reality is mediated, dictated back to us in varying forms. She is deeply invested in vast inversion of imperial/masculine archetypes, power dynamics, and ideologies. And, the reduction of hyper categorical, industrialized research.

Marti Clemmons (they/them) is an Archives Technician at Portland State University’s Special Collections and University Archives located in the Millar Library and previously worked as the Archivist for KBOO Radio. They are interested in using archives as a place for Queer activism.

Gilah Tenenbaum (she/her) was born and raised near Boston. B.A. Government and Political Science, Boston University, 1970; J.D. Northwestern School of Law of Lewis and Clark College, Member Cornelius Honor Society and recipient of the first World Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Progress of Women’s Rights Through Law, 1978. Admitted to Oregon State Bar 1978.