Category: Issue 2: Perception

Create More Space Than You Take Up

Text by Tia Kramer in conversation with Maria del Carmen Montoya

Maria del Carmen Montoya is an exuberant, warm and concise artist whose desire to create meaningful connections with people is contagious. I was lucky enough to talk with her about her creative passions and to learn what motivates her work as a collaborator in Ghana Think Tank and educator at George Washington University Corcoran School of Art and Design.

Within the world of Social Practice, Ghana Think Tank is a renowned international collective that flips the script on traditional international development by setting up think tanks in “third world” countries and asking them to solve the problems of people living in the “first world.” Carmen joined Ghana Think Tank founders Christopher Robbins and John Ewing in 2009 and since then they have founded think tanks all over the globe and at home in the US, always challenging the common assumptions of who is in need and inverting the typical hierarchy of expertise. For example, in the Mexican Border Project, Ghana Think Tank collected problems on the theme of immigration from civilian “Minutemen” and “Patriot” groups and brought them to be solved by undocumented workers in San Diego and recently deported immigrants in Tijuana. When Ghana Think Tank looks to undocumented workers, deported immigrants, Moroccans or Iranians for solutions, they elevate their knowledge, a wisdom often dismissed by systems of power in the name of “progress”. Ghana Think Tank’s act of listening is radical, deeply affecting both the interviewee and those who are seeking solutions to their problems.

At the start of our interview Carmen told me about a very important aspect of her identity: where she is “from.” Having grown up on the northern outskirts of Houston, TX in a neighborhood she called the barrio, gave her rich and complicated experiences of both belonging and exclusion, often being seen as the indigent other. She draws upon these experiences when doing her work. She has returned to Houston, a number of times creating work there with Ghana Think Tank.

Currently, Carmen loves living in Washington, DC, a city that is “ostensibly, the seat of political power in United States.” Here she holds a post as Assistant Professor in Sculpture and Spatial Practices at George Washington University’s Corcoran School of Art and Design. Carmen is married to a supportive artist and has two young children who can often be seen helping with her art projects.

TK: I would love for you to begin by talking a little bit about what you mean when you say that you are “interested in the communal process of meaning making?”

CM: Yeah. It’s kinda meta right? As far back as I can remember in my life, my experiences have felt most real when they have been shared with other people. For me, participation is critical to understanding the world I live in. I learn by doing. But I’m not naive about this idea of participation, especially in the context of socially engaged art. We’re all at different places in our lives. Sometimes we can’t come to the same place, emotionally, physically, conceptually for so many reasons like our access to resources, our age, our daily routines. I believe artists must work to create opportunities for people to be present and to bear witness even when participation is not an option. Sharing an experience makes it possible to refer to it with other people. If you did it alone, then you have yourself. But if you did it together, there are all these other eyes and minds on this thing that happened. When we share a moment, whether as participants or as witnesses, we can try to understand it together. For me it is the most honest and effective way to know things. This shared knowing sets the stage for collective action.

TK: Yes. That resonates deeply with me. And given this experience it makes sense that your work is based in conversation with individuals and groups. Can you share with me a particular conversation in your life that was catalytic for you?

CM: Oh yes. So we [Ghana Think Tank] were working in Corona, Queens as part of the Open Door Commission at the Queens Museum. John [Ewing] and I had gone to a community teach-in for young men about how to act when approached by police on the street. Police harassment of young Black and Latino males in Corona continues to be a huge problem. We were still in the research phase of the project and we wanted to learn about how community members were coming together to help each other address this issue. The room was full, interestingly enough, of grandmothers. John and I didn’t look like anybody else in that room. We were definitely the outsiders, a position we often find ourselves in when implementing the Ghana ThinkTank process.

After the presentation one of the women, came up to me and she introduced herself. She was very proper and well spoken and she said, “Good evening, my name is Violet. I’m an octogenarian. Do you know what that is?” I thought to myself (Thank god I know what that is!) I said, “Yes, Are you 80? Or 81? Or 84?” She smiled and she said, “What are you doing here?” It was such an open, honest, but pretty aggressive question. And she was looking at me; usually people look at John but she was interested in what I was doing there. I responded, “Well, I’m an artist and I’m here to listen and to learn about the concerns of your community.”

And she said, “Oh, an artist! So are you a painter?” And I said, “No”. And then she said, “Oh then you draw really well?” And I said, “Well, not really, I mean I draw ok but not great.” That seemed to peak her interest. “So what kind of an artist are you?, “ she asked. It was such an intense, existential question to have in that very moment. I don’t know where it came from – but I said, “Well, think about what a painter is doing when they render a landscape, it’s never exactly like the thing that’s out there in the world. The artist is asking you to look at the fields, the sky, the horizon in another way. And, that’s what I’m asking you to do, only we’re talking about people and relationships.”

She took a moment to think and she said, “Oh! Well, then I see you are an artist.” I felt so entirely validated in that moment. This brilliant, engaged woman understood the value of work like this and that it is art. I am so grateful to Violet for asking her questions in an such an exacting way. She wasn’t trying to make me feel good or give me an opportunity, she wanted to know for herself what on Earth I was doing there. That exchange gave me the understanding and language to express what I’m doing in a way that nobody had ever done before.

TK : You mentioned your work in Queens, but you also have spent a lot of time in conversations with your think tank teams in so called “developing” or “third world” countries. Can you share an example from a specific team that you have worked with closely?

CM: Sure, in 2013 the US State Department and the Bronx Museum selected Ghana Think Tank to do work as cultural ambassadors in Morocco. The idea was to activate a full range of diplomatic tools, in this case the visual arts. American artists were sent abroad to collaborate with local artists on a variety of community based projects in hopes of fostering greater intercultural understanding.

We arrived in a small Moroccan village, just about 45 minutes outside of Marrakech. And there we were working with the really lovely folks, at Dar al-Ma’mûn, an international residency that focuses on artists and literary translators. They have one of the most active translation centers in all of that region focusing on French, English, Arabic, and Spanish. And they connected us with a group of artists and teachers that were working in the area. This group melded magically.

As part of the project we transformed a donkey cart into a solar powered mobile tea lounge. We used to travel around the more rural areas asking Moroccans for help.

One of the problems that we brought with us to Morocco was that even in cities people find ways to isolate themselves from each other, the doors of home are hidden by shrubbery, they tend to face away from the street if possible. The Moroccans were really interested in this issue of social isolation. They said, your culture is totally obsessed with single family homes and maybe it’s really your architecture that’s your problem. You should have architecture that’s more like ours. In the Moroccan riad doors all face a shared central courtyard and you can’t help but see each other when coming and going.

This suggestion became one of our most ambitious and far reaching projects ever, The American Riad. We’ve teamed up with Oakland Avenue Artist Coalition, the North End Woodward Community Organization, Central Detroit Christian CDC, and Affirming Love Ministries Church, to build a Moroccan style riad in the North end of Detroit. This art and architecture collaboration will transform abandoned buildings and empty lots into affordable housing around a shared courtyard filled with edible gardens. The site will be deeded as a land trust and an equity coop to ensure that the homes remain affordable in perpetuity. One of our main goals is to create an art based model for introducing art into a community while simultaneously resisting gentrification. As you can imagine taking on this complex solution really intensified our relationship with the Moroccan Think Tank.

TK: How does this team and other people you know in that region of the world perceive and understand Ghana Think Tank’s work?

The Moroccan Think Tank was really interested in why outsiders were there, in their rural communities, asking for assistance. Some found the process novel and an opportunity to take a stab at American culture, most were truly interested in trying to help. They also found it very interesting to consider the heterogeneity of the United States.

For example, during another session in the mobile tea lounge, we found ourselves once again analysing this problem of social isolation. One woman brought forward a beautiful quote that said that a neighbor is your responsibility and that includes anyone living up to 40 doors in any direction. Many people that day suggested we look to the Qur’an and the Hadiths to find our answers. This project was the first time that we had been able to discuss the solutions with a think tank face to face in real time and ask immediate follow up questions, “How can we bring the Qur’an as a recommendation to people living in America?” I asked. “ People follow so many faiths and belief systems it will be difficult for them to accept.” To which she replied aggressively, “You, in America, don’t even know our book. Americans don’t read the Qur’an, they burn it!” The conversation suddenly became very intense with people yelling angrily in many languages. I remember Sarah, my translator, putting her arm across me and yelling, “Don’t blame her, she’s not even really American, she’s Mexican.” Some people seemed confused. “No, no, I am American, well, sort of, Mexican-American. It’s complicated.” I interjected. Abid, the donkey cart driver, whistled loudly and we all quieted down. Then the woman asked me if I had ever read the Qur’an. “No,” I admitted. This was a real wake up moment for me because I had studied philosophy and theology as an undergraduate and had read many cultures’ holy books. “Well, why don’t you start there,” said the woman. What a beautiful, gentle and potentially enlightening intervention. This solution resulted in a series of Qur’an readings all over the country in libraries, schools, and homes (starting with my own) and on one windy roof-top at Portland State University as part of Open Engagement 2013.

Another exchange that might help answer this question took place in a rural olive grove on a warm afternoon. The project was being funded in part by the US State Department and there was significant oversight by that office. Several of the problems that we proposed taking to Morocco were considered “inappropriate,” problems like childhood obesity, lack of political freedom in the US and PowerPoint as a brain-numbing presentation tool. The reasons varied with the most common being that “The Moroccans just won’t understand. They don’t have the context for this.” This type of paternalism is a big part of what Ghana ThinkTank is responding to and we were determined to bring the problems that Americans had submitted– all of them.

We often try to work with groups that already have a relationship with each other because it tends to create a comfortable scene and fuels conversation. That afternoon we had been invited to meet with a philosophy study group. As we sat among the trees, the participants slowly passed the problems around the circle, really pondering the issues. After some time one young man stood up and said, “I see! For Sartre, the other is hell but for Ghana ThinkTank, the other is the solution!” What a moment! This was the most succinct and accurate statement ever made about our project.

TK: Your Mexican Border Project differed from many other Ghana Think Tank projects because many of the people you were working with were in precarious legal situations and much of the work had to remain anonymous. One aspect of this project included collaborating with Torolab, and award-winning Mexican art and design group to “create a border cart designed to help people cross the US/Mexican border. Outfitted with interactive screens, the cart allowed people to present problems and give solutions pertaining to immigration and the border, creating a public think tank about the border, at the border.”

What surprised you most about working on the Mexican Border Project?

CM: It was so surprising. It was really, really surprising what happened when we went to the border. We were on the Mexican side of the border and we wanted to cross with the cart into the US, so we were traveling against the power dynamic. We had worked on the border cart for months and not just us, all the wonderful people at La Granja, Torolab’s community base. Through all this work, the object had become quite precious. All the times I’ve crossed into Mexico, it’s no big deal. The lines are short and move fast. But getting in to the US is a lot harder. We were concerned that the cart would get confiscated and we wouldn’t be able to complete the think tank session. Add to that that every single time I cross into the US from Mexico, I am “randomly selected for additional screening,” every single time. What if they confiscate the cart? What if one of us, probably me because I’m the Chicana, gets arrested? We made copies of passports, had important numbers set in our phones. We had this idea in our minds that the border patrol were going to make things really hard for us.

So there we are with the cart and we’re pushing it along the pedestrian lane. It’s brightly colored and we’re talking to people, inviting them to sit and chat, to have a drink– creating quite a ruckus. Of course the Border Patrol stop us and ask us what we are doing. They are armed, in riot gear, because I guess that is what they wear all the time now and not smiling. I took the most honest route I could and I just said, “Well, we’re here on the border, we’re artists, we’re trying to open a critical dialogic space about immigration. And we want it to be in conversation with the people who are living their daily lives on either side of these issues. And so we thought the best place to do that would be here on the border itself.”

It was amazing. The Border Patrol guys looked at each other and they were like, “Wow, yeah. We really need that. We REALLY need that. Nobody is asking us about that.” One guy got on his walkie-talkie and called up ahead to ask for help. “Where do you want the cart?” he asked me. “Uhmm.. up there?” I said. Just then two other border patrol showed up and the four of them hoisted the cart up and over the barrier and we were on our way. It was AWESOME. I was completely set to be detained, to have my passport confiscated, to have the cart impounded and to have to call my husband from a border town jail. None of that happened. All we did was talk to real people in real language. For me, it was one of the most enlightening moments of this project and there have been many.

TK: Did, that cause any shift in the project? Was there any action that changed because of that experience?

CM: I don’t think it shifted the project at all because we were set to do this one way or another. Our plan was the same as always– be respectful, try really hard and deal with the consequences of whatever happens. What I do think it did in that moment, when people saw the border patrol agents carrying the cart, is that it lifted some of the fear of interacting with us. I think on some level it might have even given us a little bit of legitimacy. A lot of people were really suspicious. It’s a scary topic, immigration and one’s status.

TK: Based on your diverse experiences, what advice you would give to young social practice artists?

CM: Pose your own questions. There is something very different at stake for participants, for community liaisons, for institutions, and for the artist. And I think it’s really important to do as much as you can to bring those concerns into conversation with each other. I always try to be honest about what is at stake for me personally in any project. So when we worked on the issue of climate change, when we worked with the immigration conundrum on the border, when we addressed police abuse of power in NYC, I look for my own story in that. And I am prepared to be the first to share. What is at stake for a participant is real. What is at stake for you is real. What’s at stake for the institution is real. It is essential that everyone is bringing what’s at stake for them to the table in an open, honest way.

The other thing is that I think it is important to create more space than you take up. As socially engaged practitioners, working in communities, we are taking up space. People have things to do and they are taking time out of their lives to speak to us, to participate, to contribute to our projects, they help us build them, to implement them. And so it is important to not be in denial about that, about the space that we’re taking up in people’s lives. I think one of the ways that we create space is when we pass the mic. By that I mean when we create a context for people to talk about what’s really important to them. This is what allows the work to become their work too.

Art Education & Public Programming within Art Institutions

Text by Brianna Ortega in conversation with Jennelyn Tumalad

A Conversational Interview with Jennelyn Tumalad, current Project Coordinator of Education at the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles, CA.

You focused your Master’s thesis at Pratt Institute on “Socially Engaged Art and Educators in the Museum” and have worked within many institutions, specifically within the educational programming and public programs departments. How have museums and institutions perceived your “socially engaged art practices”, specially related to your different projects like “College Night” at the Getty and others?

Socially engaged practices to me, are practices in which programmers/educators/artists are responsive to the needs of a community and work with them to create resources, programs, experiences, and opportunities they feel they most need. This is not unlike museum programming, especially for education departments. Museums identify as public educational institutions that serve their community. I started creating parallels between the two practices–museum education and socially engaged art–while I was working as an educator in museums in NYC and studying art history, focusing on contemporary art movements such as activist art, art and social practice, and socially engaged art). I chose this due to seeing a lot of parallels with the work that I was doing as a freelance educator.

As far as how museums have perceived my socially engaged art practices… I think it’s important to acknowledge the difference between supporting change and radical ideas, and actually committing to the time, energy, persistence, and self-work that actually goes into making long-term systemic change.

I think the most directly related project I’ve developed in hopes to really trying to incorporate socially engaged practices into museum programming is one that I’m about to implement this January. When I say “socially engaged practices,” I’m referring to ways in which socially engaged artists involve the communities they work with. My program structure uses “YPAR” Youth-led participatory action research. In the original curriculum that I developed, the participating youth in this program are active agents in identifying problems within their community and coming to answers they felt would help “solve” these issues. I pitched this program and had incredibly positive feedback about it being “youth-led” and that students would feel empowered and become active agents in this program, but ultimately the core of this program ended up changing a lot from original inception of the idea to actual implementation.

How do you see socially engaged art functioning within an institution?

It’s hard, you know, because museums exist within the art world, which in and of itself likes to exist outside of the real world, but ultimately the art world is within the real world, which has its own systemic injustices. I think what is really dark about the art world is that it likes to portray that it’s different. And it’s not. And I think that’s one thing it needs to own up to and stop performing. Many art spaces profit on being viewed as an activist and progressive space, but the reality is that many institutions are ultimately funded by the 1%. That’s something that I’ve had to come to terms with when working within museum spaces.

The goals that museum educators have are a lot of the same goals that socially engaged artists have. Pablo Helguera’s piece, Librería Donceles, was a travelling spanish-language bookstore and community space that hosted programming that was responsive to the spanish speaking community of each city it occupied; a project like this is exactly what museum education and public programming seeks to accomplish. It creates and strengthens the local community, it connects people closer to art and ideas, it develops empathy and critical thinking about the world around you. It is not surprising that Pablo Helguera is both a socially engaged artist and the Director of Adult and Academic Programs at the Museum of Modern Art.

Another example of the blurry line between artist and educator is a teacher’s resource guide from the Guggenheim’s education department for their exhibition, “Under the Same Sun: Art from Latin America Today” that helps teachers and visitors with different ways of navigating the gallery space. It was entirely comprised of conceptual art and felt like an instructional fluxus piece. I said to myself, “this is literally art. What is the difference here?”

While attending the NAEA conference a few years ago, I attended an a presentation from an art education PhD candidate on the topic of how K-12 art educators can lose their identity of being an artist once they start teaching. It made me realize that many art educators have such a traditional view of what art is. And it’s really not in line with where art history is in the moment at all. It’s very confusing. It made me think, “So we expect everyone who teaches foundational k-12 art education to have a really traditional viewpoint of what art is, such as drawing a still life, one point perspective, or essentially that art is how accurately you can draw something, or even that art can only be an object. And drawing it accurately…”

What you are saying makes total sense.

And yet everyone who teaches at the college level are all practicing artists. They all know art history in its entire scope. This guy was talking about his research to a bunch of very traditional K-12 art educators. He said that art educators normally define artists as those producing artwork and showing at a gallery. They see art as only making a product. He asserts that art educators would continue to identify as artists if they start to expand their viewpoint of what art is, which has been something that’s been happening, since the 60s or earlier (remember anti-art and Dada?). And everyone’s mind was blown: “wait what, art and social practice?”

Ultimately, socially engaged artists and educators within institutions can learn a lot from each other. Educators can become inspired to think more about their practice in a creative way and allow themselves to see that the work that they do is artistic in itself when approached with purpose and creativity. But, socially engaged artists can strongly benefit from some of the very practical methods educators implement in their discipline: things like measuring impact, applying standards to their work, and developing pedagogical strategy.

Continuing with the perception of institutions on socially engaged art… How have any of your socially engaged art practices within institutions changed their perception in a new way?

I think it’s important to think about who is making up an institutions’ perception. If it’s the people funding the museum or the higher powers of the institution, I wish I knew! I’m still quite young in my career, and have only been able to “sit at the table” with director’s and decision makers a handful of times. I think it goes back to being patient for change and back to the ideas I mentioned before that long-term systemic change takes time. So it’s important to see small wins and remember that those small shifts can build up to create the change you want to see.

For example, the longest I’ve worked on administrative staff at a museum was at the J. Paul Getty Museum for 2 years in varying capacities (moving from Graduate Intern to a Program Coordinator in those two years, always focusing on college audiences and public artist programs). I worked tirelessly to incorporate a College Advisory Board to help plan their annual college night. In this board, I involved as diverse a range of students that my one man operation could recruit. I built out a program where we met weekly to discuss and think critically about what College Night meant to them and their community and how we could make it a program that truly represented the diversity of interests, needs, and work happening in college audiences in LA County. This involvement and collaboration caused the attendance to skyrocket compared to the previous year: the number of participants rose from 1600 to 2600 in attendance. It was as simple as involving the community, valuing their perspective, and nurturing the relationship so that they all felt a stake and desire to see this event be successful. From that experience, the College Advisory Board’s involvement continued, it allowed for the museum to provide travel stipends for future College Advisory Board members, and increased the event’s program budget for the next fiscal year.

Again, museums are really quick to say, “Yes! Let’s do it,” when they hear about programs and initiatives that mention social justice, equity, or incorporate any of the strategies that are informed by socially engaged art. They want to quickly flip a switch to say, “yeah, we are equitable, we serve the local community, and we are diverse.” To get to this point, it takes real patience and systemic change, and having every single stakeholder that’s a part of the program actually being committed to the work of making that change.

What is notMoMA?

Text by Sara Krajewski

WStephanie Syjuco’s notMoMA (2010) is a work of conceptual art and social engagement, and the first work of social practice art to enter the Portland Art Museum’s collection. As a gesture of institutional critique, notMoMA questions the value and authority given to museum collections, who establishes and upholds that value, and how access to collections is granted. The Museum acquired the work in 2016 as a donation from the Portland State University’s Art & Social Practice program. It is unlike anything the Museum has collected, so far.

To exhibit notMoMA, Syjuco asks the presenting institution to identify and engage a group of artists. The makeup of the group is completely open and in its three iterations to date it has focused on students from middle school to college. The presenter also designates a curator (again, who takes that role is open for interpretation) and the curator’s job is to select works from the Museum of Modern Art’s online collection. The group of artists are then tasked with recreating the selected works, using only the digital reproduction available on MoMA’s website as their source material. The intention is to refabricate the works to near actual size, employing readily accessible and affordable art supplies or scavenged things. When finished, the re-fabrications are displayed in a gallery deemed “notMoMA” and presented with interpretative labels identifying the original art works and original artists, alongside the names of the re-fabricators.

The work came to the attention of folks at PSU’s Art & Social Practice program when it was produced at Washington State University, Pullman. notMoMA was soon wrapped into an upcoming event “See You Again” that a group of PSU students were creating for the Portland Art Museum’s Shine A Light series of socially engaged programs. The “See You Again” collaborators Roz Crews, Amanda Leigh Evans, Erin Charpentier, Emily Fitzgerald, Zachary Gough, Harrell Fletcher, Derek Hamm, Renee Sills, and Arianna Warner decided to take their programming honorarium of $2000 and use it to purchase a work of social practice art that they would donate to the Museum. They selected pieces by Ariana Jacob, Paul Ramirez Jonas, Ben Kinmont, Carmen Papalia, Pedro Reyes, and notMoMA by Syjuco. On Sunday, May 31st, 2015, a large group of guests attended a cocktail hour and heard impassioned advocates make political style speeches to sway the audience toward selecting one work. A caucus style vote commenced until, at evening’s end, notMoMA emerged the winner.

OK, notMoMA was selected. Then what? Stephanie Parrish, Associate Director of Programs at PAM and coordinator of the Shine A Light series, advised the PSU students to sit tight: to guide the work through the acquisition process, it was going to need a strong advocate in the curatorial department. That was me. In September 2015, I came on board at PAM, with a goal to reinvigorate the contemporary art program and I set about establishing a vision to welcome a much broader array of artistic practices and expression. I have always embraced an artist-centered approach to creating exhibitions and have had the opportunity to provide artists with platforms for experimental works. But to this point, I had not yet been in a position to bring a performative, socially-engaged work into an institutional collection.

The Museum, like all public, non-profit collecting institutions in the U.S., has a collection committee appointed by the Board of Trustees. This committee’s role is to provide oversight and approval of all purchases and donations that enter the Museum’s collection. Each PAM curator presents works of art to this group in meetings that take place every other month. I knew that notMoMA would be a challenge because we don’t have a history of collecting this type of work and it would be an educational moment for our committee members. I decided to do some advance prep with the committee co-chairmen to discuss the work and use that discussion to be prepare for questions that undoubtedly would arise: What exactly are we collecting? Will this create concern for MoMA that we are supporting this work? Questions came up about appropriation, copyright infringement, and how to ascertain the long-term value and relevancy of the work when it is not a fixed object or experience. We discussed the professional standards for collecting conceptual art and performance through certificates of authenticity; I gave a primer in social practice art forms and outlined our ongoing relationship with PSU’s Art & Social Practice program. A rigorous debate ensued. Even with lingering concerns, the committee voted to accept the piece.

With the official stamp of approval, the accessioning process began. In conversation with the PSU students, they expressed a desire to have a material form for the work that they could deliver. We settled on a set of instructions with attendant appendices that illustrate past iterations of the work. The instructions serve as our certificate of authenticity. An institutional concern came up around the artwork’s transfer of ownership. When a work of art enters the Museum collection, the Museum retains rights to it as a special class of property. We did not have any precedents for a process-oriented, idea-driven piece that takes changeable physical forms. Does the Museum solely own the idea and the right to recreate the idea? What are the artist’s rights to the non-objective, to the piece as intellectual property? If an organization wanted to present the work with the artist, would they have to acknowledge “collection of the Portland Art Museum”? Is this work “unique,” e.g. are their editions or multiples that the artist might show or sell in the future?

notMoMA has given me reason to reflect more deeply on the categories and designations that museum collections place on works that exist in the social sphere. Specific to notMoMA, the piece concerns access to art; by virtue of the institution’s internal control systems a layer of restriction has now been added to mounting the work outside of the Museum. It raises a relevant question: is this work really collectible? What does it mean for students of social practice art to create a situation where a socially-engaged work goes out of circulation, frozen in an institutional vault? Wouldn’t the work and its ideas be equally, or even better, served by multiple well-documented presentations that would be more readily available to larger audiences? The “See You Again” requests certainly asked the institution to stretch its definitions and its categories, and that is indisputably good and necessary. But did the act of collecting notMoMA stop it from reaching a heightened potential in the real world where real questions get addressed?

After all, Syjuco intends that notMoMA bridge a gap in students’ understandings of “high art” and invites them to come to a greater comprehension via their own do-it-yourself collective vision. Whether considered copies, translations, or even mis-translations, all resulting works are unique expressions in their own right. They exist outside the institutional framework, even in healthy opposition to it. As an exhibition illicitly “borrowed” from MOMA’s collection, notMoMA creates a dialogue between a localized audience and a powerful cultural institution that may be inaccessible to the participants and public alike due to geographical, economic and socio-cultural barriers. Syjuco also reflects on the aura of original works of art, challenges the consolidation of cultural wealth in major institutions, and reasserts the physical experience of art in the digital age. Now that it is in another institutions collection, does this affiliation further complicate the work? Or could it be seen to neutralize its criticism some?

After acquiring the piece, I felt an urgency to activate the work and justify its “value”. We presented notMoMA in the context of our year-long We.Construct.Marvels.Between.Monuments. series led by guest artistic director Libby Werbel. Werbel responded enthusiastically to including the work in chapter 3, MARVELS. She invited curators Shir Ly Grisanti (c3:initiative), Mercedes Orozco (UNA Gallery) and Melanie Flood (Melanie Flood Projects) to select MoMA works and area high school students from Jefferson High School, Gresham High School, and Reynolds High School to be the artists/re-fabricators. We also engaged a side project with c3:initiative, creating a space for documenting the process and giving more recognition to the student artists. We even got a best of 2018 mention in Artforum, courtesy of artist John Riepenhoff, probably the first critical attention the Museum has had in the print edition of the journal.

I am pleased and proud that the Museum has engaged with an important work of art, and of course I am pleased and proud that we can count it in our collection. Stephanie Syjuco continues to challenge me with the depth and complexity of her artistic inquiry. I’m grateful to the PSU Art & Social Practice program for making this engagement possible and allowing for this reflection of a wonderfully complex work. The number of questions notMoMA and the event/intention of See You Again continue to have for me attests to the importance of the work and adds dimension to the continuing relationship between the Museum and the PSU program.

About the author:

Sara Krajewski is the Robert and Mercedes Eichholz Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Portland Art Museum, Oregon. Over her three-year tenure at the Portland Art Museum, Krajewski has reinvigorated the contemporary art program through exhibitions, commissions, collection development, and publications, and she has fostered collaborations that bring together artists, curators, educators, and the public to ask questions around access, equity, and new institutional models. Recent and upcoming exhibition projects include: Hank Willis Thomas: All Things Being Equal; We.Construct.Marvels.Between.Monuments.; Josh Kline: Freedom; and Placing the Golden Spike: Landscapes of the Anthropocene. Krajewski holds degrees in Art History from the University of Wisconsin (BA) and Williams College (MA) and has been a contemporary art curator for twenty years, holding prior positions at the Harvard Art Museum, the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, the Henry Art Gallery, and INOVA/Institute of Visual Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. A specialist in transdisciplinary artistic practices, Krajewski was awarded a curatorial research fellowship from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and is a 2019 fellow at the Center for Curatorial Leadership.

Where Social Work Meets Art and Social Practice

Text by Brianna Ortega in conversation with Dr. Laura Burney Nissen

Conversational Interview with Dr. Laura Burney Nissen, Dean of the School of Social Work at Portland State University and Professor

Definition of Social Work (from Google): Social work is an academic discipline and profession that concerns itself with individuals, families, groups and communities in an effort to enhance social functioning and overall well-being.

Can you tell me a little bit about your background and how this plays into your current perception?

I studied art as an undergrad and was raised by artist parents, and then later, “switched” to social work out of a deep desire to make the world a better place. I never stopped having my own art practice though…it has been a cornerstone of my life. Somewhere along the line, we bought into this false choice that we had to choose “you have to be an artist” or “you’re a social worker” and that’s an unacceptable choice. I reject that choice. But, now I’m 56. I wish I would’ve rejected it sooner. The last couple years, I’ve been exploring the intersection of the arts and social change, and community wellbeing and individual well being.

Last year, the Social Practice Program started to attract me for lots of reasons. The future of social work and the future of most professions is interdisciplinary work. No one group has the answer and the answer to many of the challenges we are facing are the spaces in between our profession lenses, the ways of thinking, and our community partners.

I’ve heard that the School of Social Work has collaborated a few times with the Social Practice Program.

So, last year, I invited the Art & Social Practice students over to the School of Social Work just to have dinner with some Social Work students who were also very intrigued by this. And we just talked and nothing really came of it per say beyond a deep desire to “do more” and get to know each other better. But we are going to do another one this year. One thing the students said last year was, “let’s do it again, and next year, let’s talk about how would we both tackle a social problem, like, let’s say… homelessness.” So how would Social Workers approach that? But how would artists approach that? And is there more that we can learn from each other about how to be more creative and effective through learning from each other.

To get two different disciplines to think about the same idea or project…

Right. And I have loved being a social worker. I’ve had incredible experiences and it has been deeply professionally rewarding. I don’t have any regrets. And all of the things I am grateful for, I am grateful for my art background as I’ve been a social worker. I actually think my art background did more to prepare me for the kind of problem solving I do in social work.

That’s inspiring to hear as creativity is something often undervalued. But, to me, the most intelligent people are often the most creative.

Yes, I totally agree. And I valued the Social Work education, but I’m glad it came after my training as an artist. Because I approach everything with an unlimited amount of problem solving energy. Too many people look at a problem and think “there’s 3 ways to solve this.” No there’s really not. There’s really an unlimited number ways to solve an issue, but we’re just not always using them.

So with your experience in the School of Social Work… what is yours and the school’s perception of the Art & Social Practice program?

Last year I was able to get an article published about art and Social Work together. I was waiting to write that academic article for 20 years and I finally did it. When we started our 2018-2019 academic year, we had a big event to welcome the MSW students. I mentioned that this is a big passion of mine (art and social change) and I’m doing a lot of thinking work about bridge-building between these two areas. I really am a bridge between two areas because I understand both languages. I developed a shortlist of several students that were also interested in this, who were also artists… musicians or visual artists or actors. There’s always intensely creative souls that become social workers. So I didn’t have to do much convincing with these people.

The bigger challenge is, and what I have to figure out now is this something that every Social Worker can benefit from? And yeah, I think there is. I think people who don’t see the connection is my next big challenge. Because I think a lot of people look at it and think, aw, that’s cute. They don’t take it very seriously.

I can tell you that I don’t know a joint degree program anywhere in the country that you can get an MFA and an MSW together. But, you can get an MSW and a law degree. You can get an MSW and a Public Health degree… and several others. (Art and Social Work) is not a combination that is well understood or well recognized. But, maybe someday we’ll find a way to do that here at PSU.

I’d be very interested to see what a someone would do with both a Social Work degree and an Art degree. To me, those are two very powerful people and a powerful combo.

What do you think are the parallels between the two?

Social work definitely is a profession, but it’s also a passion. Nobody is in Social Work because they go into it for purely intellectual reasons. Social Work is a passion. People are passionate about wellbeing. They’re passionate about injustice. They’re passionate about healing and advocacy and problem solving. Artists are similar. Art is a profession; you have professional artists. Art is not just a profession, it is also a passion. People who are artists are also interested in a different lens. I don’t want to say all artists are interested in social justice and wellbeing, but I think all artists are interested in problem solving and communication, and many artists are interested in a lot of the same things as Social Workers: they’re interested in the meaning of life, what creativity contributes to the human experience. Both disciplines seek for their work to mean something and both professions are very creative.

Because so much of Social Work is done within bureaucracies and within rigid cannons of theory about theory, sometimes Social Work can be uncreative. It can suffer from a lot of bureaucracy and I have some deep disappointments about that – that is how social workers burn out. I don’t know much about how artists can get burned out – but I know they do too. Through my own process making art, I know that you can have ups and downs. You’re not highly successful all the time. But I don’t think both groups get burned out in the same way – maybe there is something we can learn from each other about burnout and renewal as well.

I don’t have all the answers. Right? Where exactly is the bridge? One thing in my heart that I feel deeply about is that creativity is really good for people and really healthy. Where art is thriving in communities–those are little pockets of wellbeing. And Social Workers really care about how to help individuals, families, and communities to be well. As I’m looking over a person’s life, a community’s life, as much as I’m checking on poverty, illness, and mental health, I should also be checking on the presence of art or creativity in these spaces and asking if it is possible that those things can help. I deeply believe they could and there’s increasingly sound research supporting that these are really powerful sources of healing energy.

We need more bridges.

More bridges and less walls.

Any last thoughts on the Art & Social practice program?

I have a deep respect for the arts and a deep respect for artists. I think the people that are doing the Art & Social Practice program are amazing and committed. I think this is one of the cutting edge areas. This is very much about the future. This program is visionary and exciting and has so much to offer the world. I’m really excited about it and I celebrate it, but most of all I respect it. I don’t think it’s fluffy. I don’t think it’s easy. I think it’s hard work. Hard intellectual work. Hard community work. I just have a deep respect for it. I’m glad it’s there.

My speciality is addiction, so I know how mental health and addictive health works. I am committed to finding new kinds of solutions and building more opportunities for systems to reflect what works. I’d love to see art become more a part of that. In many of the spaces I occupy, I don’t think the arts get adequate respect for the kind of problem solving that we engage in on that front. All of this work I want to do I do because I respect it, and I respect the people who are doing it.

I have a friend who is working through the questions “Is all social work art? And are all Social Workers artists?” Well, I don’t think they are. I don’t actually. I think artists are artists and social workers are social workers. Like, I happen to be both. And you are both. But, if you are both, you have to really dedicate yourself to both. Art is not easy. It takes courage and dedication.

Laura is going to be spending her upcoming sabbatical exploring and studying the intersection of art and social change in New York, Los Angeles, Pennsylvania, and Portland.

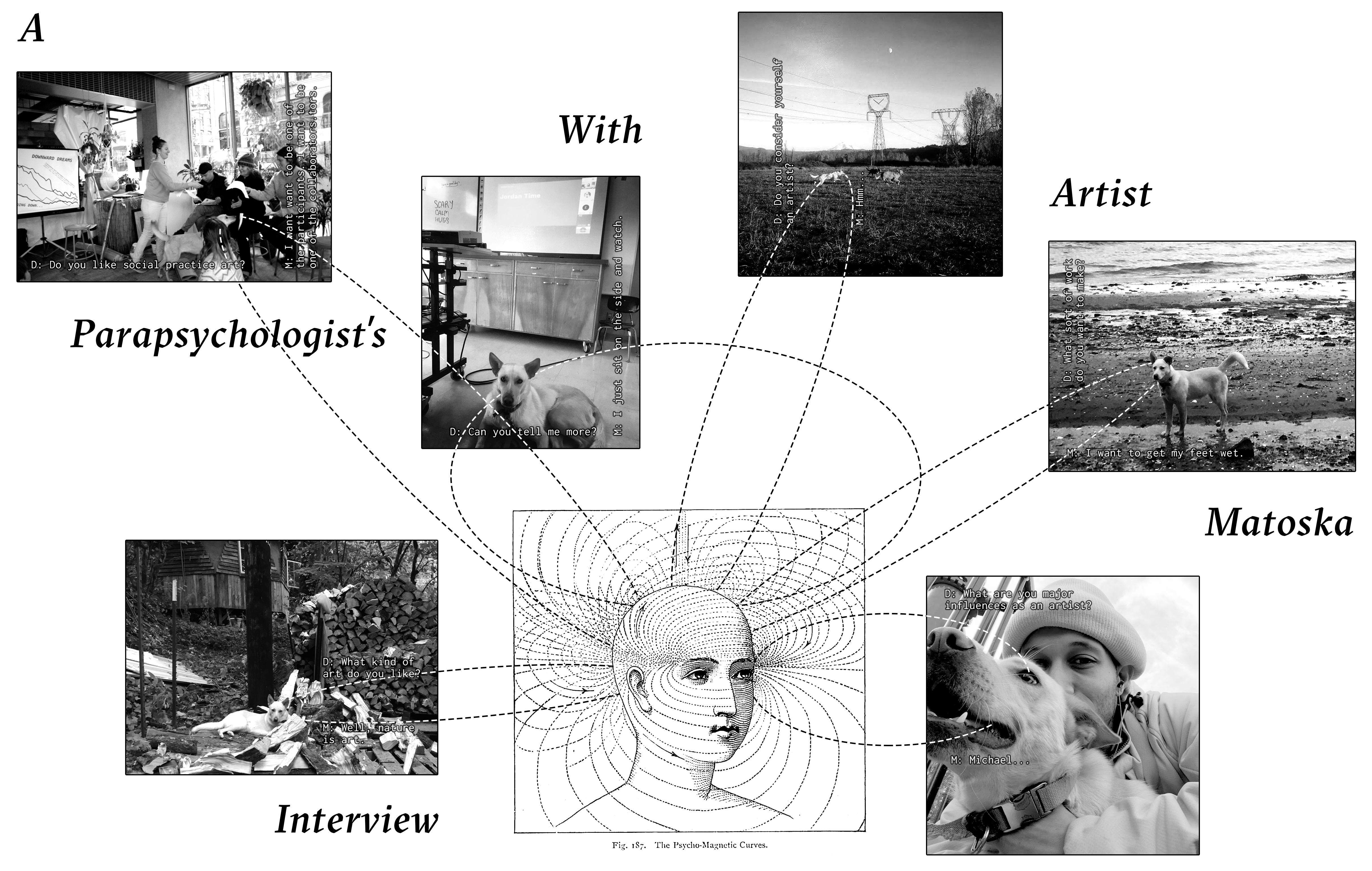

Artist Matoska’s Interview with a Parapsychologist

Text by Matoska with Deborah Erickson, PHD and Artist Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr.

An Interview With a Dog About Art

Towards the end of December, 2018, we set up a unconventional sort of interview to further expand the lines of inquiry towards the perception of art. We contacted Dr. Deborah Erickson, a parapsychologist and animal communicator, to conduct an interview with Matoska, the companion of Artist Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr., a member of the PSU Art and Social Practice Program. We asked a series of questions to Matoska, through the facilitation of Deborah, to try and learn what are Matoska’s perceptions of art, whether they consider themselves an artist, and where they draw inspiration in the world.

Deborah: Just to frame this session for you, I’m sitting in my meditation room with a blackout mask over my eyes. I’ve spent about the last 20 minutes or so in conscious breathing, yoga breathing, visualizations, getting myself cleared of negative energy, negative entities, and asking for help from the perfect powerful Source, the Diva of animal communication, and from Matoska’s angels and archangels, to help me get clear messages from her.

Michael: Excellent.

Deborah: Okay. Can you see her? Sometimes you’ll see a physical reaction when I connect to animals in their heads. Not always, but sometimes. I’ve talked to a friend’s cats who said her cats were stomping around the house trying to figure out where I was.

Deborah: So, who’s asking questions? I’d like to take ’em just one or two at a time.

Michael: Sure. I’ll go one at a time, ’cause that makes sense.

Deborah: Okay. Let’s get started. What’s your first question for her?

Michael: The first question is, “What kind of art do you like?”

Deborah: Okay. Hold on just a sec. She’s been waiting for me, by the way. Hold on.

Deborah: So, in one of the photographs sent, Michael, her front feet were crossed. Was it posed or did she do that?

Michael: That was Matoska in her finest.

Deborah: Exactly, ’cause that’s the picture I just got when I connected with her. Very regal. Very smart. And so I introduce myself and I say, “Michael asked me to talk with you. Is that okay with you?”

Deborah: And she says, “Of course. I’ve been waiting for you.”

Deborah: For the question, “What kind of art do you like”. She kind of looked around and thought, she finally said, “Well, nature is art.” To her, the outside is art to her. And I said, “Well, okay. Do you like sculpture?” Has she ever seen sculpture? I don’t think she really understood what I meant by that. So, I think if anything, her “favorite art” would be natural things portrayed on canvas or a picture or something like that. I mean, she kind of didn’t know how to answer that question, I don’t think. And from her perspective, nature is art.

Michael: So, the question is, “Do you like social practice art?”

Deborah: How has she been exposed to this? Would she know what that means?

Michael: Well, I guess you can convey, which more questions will come up about it. She attends class with me, so for all intents and purposes, my understanding is Matoska’s also pursuing her Master of Fine Art in art and social practice. She’s never missed a class. Then often when I’m practicing, the photo of her in front of that cart, is activated by young people serving food out of it and she has been present for both iterations of that, among other interviews or meetings or engagements that are part of my practice, or others’ practices.

Deborah: Good. That helps. Hold on.

Deborah: Well, she wants to be one of the participants, one of the collaborators. She goes to class with you, but she says she just sits on the side and watches. So, she feels like she’s been sort of shuttled to the side of participating in these exchanges and she doesn’t get to play. Is she normally included or excluded from these collaborative efforts?

Michael: That’s a really great question. She, in class, definitely is kind of more just present. Sometimes she’s kind of bouncing around doing her own thing, but mostly is just relaxed. I have brought her to some of my projects, and again, she’s more present. It’s more of like a social experience for her but non-collaborative creative.

Although this article, originally, the thought was maybe interviewing the dogs who belong or are in partnership with the director of our program. But they just stay at home. Matoska’s much more present in the culture and within that, I have been thinking about collaborating with Matoska, to kind of help develop their practice in their own right.That is kind of oncoming or has slowly begun, and this interview and article is kind of part of that, kind of validating their interests as an individual. So, it’s good to know that they enjoy nature. So far we’ve done some feather collecting together. But I’m looking forward to more, for sure.

Deborah: Good. So, yeah, she wants to be engaged in these events as well. Okay, next question.

Michael: Do you consider yourself an artist, and if so, what sort of work do you want to make?

Deborah: Yeah. Hold on.

Deborah: Well, when I asked her that, I didn’t really get an answer for a while. She’s thinking about it too, and the image I got was like her splashing through a puddle. So, maybe getting her feet wet would enable her to create something. And then I got image of her walking through wet sand. Things that would imprint her footprints, that kind of thing. I sent her a picture of … You know, these elephants or animals that hold a paintbrush in their mouth?

Michael: Right.

Deborah: And put color on a canvas, and she seemed intrigued but not that interested. It was like the kind of answer, you know, it was sort of a reaction of, “Really?” That was kind of farther than she could think, I think.

Michael: Yeah. The next question is, “What are your major influences as an artist?”

Deborah: So the question is what has influenced her?

Michael: Yeah. “What are your major influences as an artist?” Should be interpreted by however she sees it.

Deborah: Okay. Hold on.

Deborah: Well, she said, “Michael … ” You, of course, as a guardian, she said, “I learn something every class,” that she has with you. Then just engaging with your friends.

Michael: Right. Well, that’s excellent. She’s got a lot of good mentors.

Michael: The final of the easier questions is, “Are you interested in collaboration in your artwork?” Which you kind of mentioned, but I don’t know whether Matoska has more to say.

Deborah: Okay. Hold on.

Deborah: Well, dogs never want to do anything alone. They always want to be engaged with us, with people. And if it’s not with us, then with other dogs. I mean, does she have a “practice” now? And if so, what does she do?

Michael: That’s a good question. I think there’s two pulls. Me trying to deduce what existing parts of her lifestyle is part of her practice. And then also what are ways that I can participate with them that feel collaborative and generative for us both? Well, I mean, again, kind of drawing from nature and pre-existing forms. Sometimes Matoska will find feathers and I’ve begun to collect them for some other purpose in the future. I also was thinking about when she was younger, they would always run to puddles, now then tend to avoid them. But we did … I would think not out of disinterest, but out of respect for my desire to not always have a wet dog. But now, we went to this place at Thousand Acres. I’ve been trying to find it again, but it was kind of like a water dirt bike park for dogs and that may be one of the happiest play sessions I’ve ever seen. So, it would be interesting to work with something there.

——– WEB Only Below ———–

Deborah: Okay. So, what have we got left?

Michael: How do you feel that the social practice program has made space for animals to be seen or heard? Also, something you kind of mentioned, but this is a more specific inquiry.

Deborah: Well, yeah, I kind of got the same. She doesn’t feel that she’s been invited to collaborate or to be part of the action or to be part of the exchanges. So, her answer to, “How do you think animals have been involved,” she’s like, “Well, I haven’t been.”

Michael: Right. Yeah. Cool. I will have to share that with the group. The next questions is: “what is your favorite work of a student that involves animals?”

Deborah: Well I can ask her and just see what I get, and sometimes I’ll get nothing. Okay. Hold on.

Deborah: Well, what I got was an image of a short woman. She has dark hair, very dark. Almost black. Cut very short, with a paintbrush in her hand, doing something on a canvas.

Michael: Hmm. Well, Xi Jie is very short and has dark hair and also Brianna is semi-short and has dark hair. Could be one of them.

Deborah: I don’t know if that matches anyone in her group that she’s ever seen or not or whatever. But Matoska wouldn’t know that. I mean, what she’d see is just a gathering, right?

Michael: What has been your favorite art exhibit and why?

Deborah: Art exhibit and why. Okay. Hold on.

Deborah: The image I get is her sitting in front of a canvas that’s pretty big. I mean not huge, but rather large, and it’s got really brilliantly blue color on it. It’s like, I don’t know, maybe an abstract? But that she remembers, that one was the image that I got from her. Don’t know if that’s anything she’s seen or not…. but that’s about all I got.

Michael: Maybe she sees water as art and the brilliant blue is the ocean.

Deborah: I don’t know.

Michael: So, does the social practice program respect a variety of animals?

Deborah: Hold on.

Deborah: Well, respect, yes. She’s allowed to attend, so she knows that that’s a privilege. So she’s respectful, yes, in that she’s allowed to attend the classes, but she hasn’t been invited to be engaged.

Michael: Right. It seems to be a common theme that needs to be addressed.

Michael: Getting to the end here. How have you grown as a dog, from watching the social practice program over the past year and a half?

Deborah: Okay. Hold on.

Deborah: Well, she said, “Everything has expanded my world.” Dogs that are regularly exposed to new experiences become very accepting and tolerant of their experiences. I had a dog trainer tell me that as a puppy, a puppy should meet 100 people before they’re three months old. That’s a lot of people. So, that’s how she feels that she’s been privileged to be exposed to all these different things that have expanded her world.

Michael: Next one is, In what ways would Matoska like to participate in the program more?

Deborah: Okay. Hold on.

Deborah: Being more engaged in the sense of people saying her name and inviting her response to something that’s going on. I don’t have any experience in trying to describe to her. I mean, she knows more than I do about what these classes are like. But nobody says her name. Nobody invites her in. Right?

Michael: Right.

Deborah: I mean, so she attends, but, again, she just feels like she’s on the sidelines.

Michael: I love it. All right. This is our final question. How do you feel about food in the program and the inclusivity of people with food? Are you included in this?

Deborah: Okay, so how does she feel about food in the program?

Michael: Yes. And the inclusivity of people with food? And then does she feel included?

Deborah: Okay. Hold on.

Deborah: Well, the image I got back was her licking her lips. But she says, “No. Nobody ever offered her anything.”

Michael: Right. That’s true. We’ll have to do a dog food event.

Deborah: Well, yeah, if her diet is strictly limited and you can still use what is her normal diet and work with it that way.

Michael: Yeah. I think it’s very possible. It’s ripe for a collaborative figuring out between her and I.

Michael: I did realize one of my partners was going to be on the call and couldn’t, but was curious about this question. The question that she has for Matoska is how my energetic and emotional state affects her.

Deborah: Oh, gotcha. Hold on.

Deborah: She says, “You get prickly when you’re angry. And you’re hard to soothe.” But she wants you to soak in her calmness and her soothing presence, when you’re upset or angry. She also said, “He’s mostly pretty even keeled.”

Michael: That’s true, but sometimes there’s times. Excellent.

Deborah: So, now you know. When you’re angry or frustrated or whatever, how she perceives you as being prickly.

Michael: Prickly. Well, I’ll have to get my calm on. She’s pretty calm, unless she’s being really excited. So, that’s all of my questions.

Deborah: Okay. So, I’ll close with Matoska and thank her for talking to me, and ask her if she has any messages for you.

Michael: Okay.

Deborah: She said, “I love our life.” She feels extremely lucky to have such a wonderful life with you, and to be taken as many places and have as many different experiences that she has had. She really loves her life. And she would like you to absorb more of her calm in your life. And just recognize her, the calming presence that she brings to your life, that you should be more aware of that and more cognizant of it and take more advantage of that.

Michael: Excellent. Tell her I appreciate the message.

Deborah: She knows!

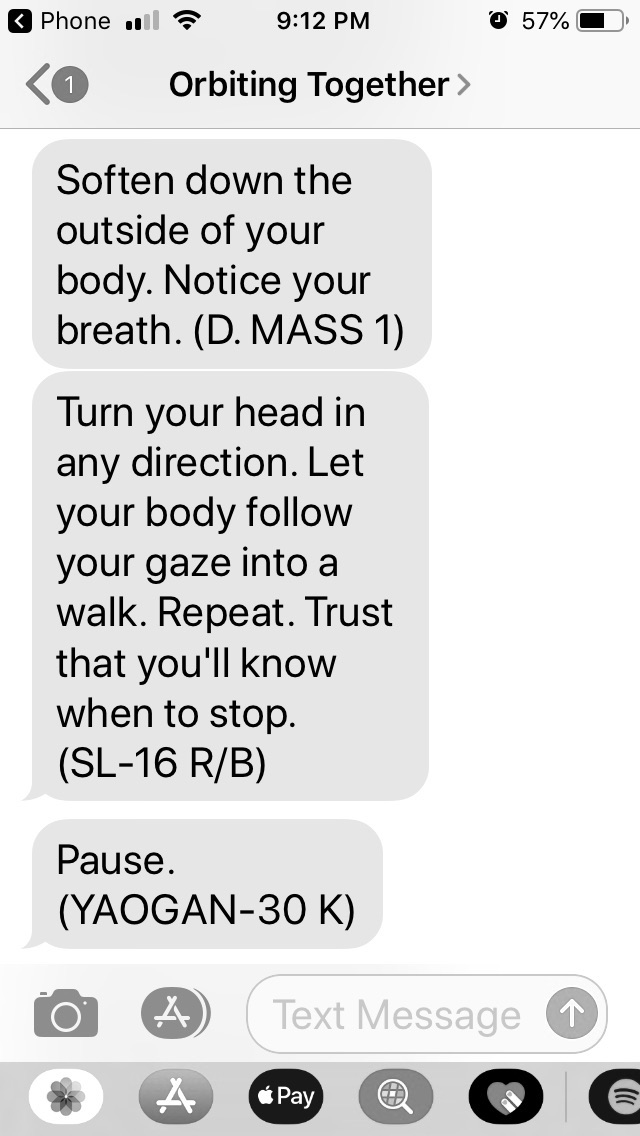

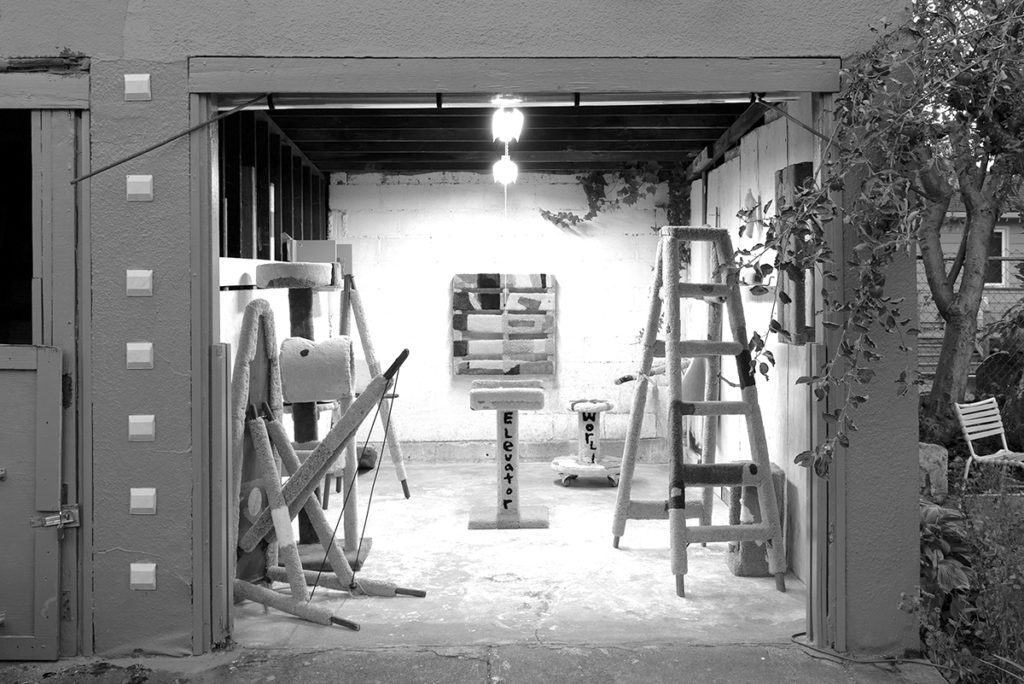

Ethnography, Socially Engaged Art and a Preponderance of Dogs

Text by Allison Rowe

A researcher’s attempt to get a new perspective

Dog is one of the most used words in field notes I recorded during the two months I spent studying a collaborative, socially engaged art project in the winter of 2018. The project that the artists worked on was not about dogs but rather about technology, somatics, and fostering embodied connections between people. It was a beautiful, complex work that helped me learn new and unexpected things about museum-supported socially engaged art, community, and generosity. The dogs who pepper my notes largely just walked by me through the space where the artwork was taking place. As an artist turned art education “ethnographer”, I diligently took note of these dogs, what they wore, how they moved, and the people who walked them. Though my mentions of dogs are brief and lack the depth of my writings about the collaborative processes of the artists and the institution I was trying to learn about, the dogs are still interwoven throughout my notes, like pinecones amongst the dense dark green branches of a fir tree. While I did not realize it then, my accidental fixation on dogs illustrates just how much one’s own life can color individual perceptions of socially engaged art, even if, like me, you are attempting to look at things in a new way.

At the time of my canine preoccupation, I was a doctoral student studying gallery and museum supported socially engaged art. I began my research project because a decade of making, talking, and reading about socially engaged art had attuned me to a gap between my lived experiences within the field and ways that others (particularly academics and museums) seemed to describe projects. I observed that much writing on socially engaged art articulated or analyzed the final outcomes of a project, never getting to what most interested me as an artist—the slow, sometimes uncomfortable, mundane ways that a collaborative, institutionally-supported work unfolds. Bishop (2012) identified how the logistics of art critical and academic research don’t always align with the structure of socially engaged art which she explained is, “an art dependent on first-hand experience, preferably over a long duration (days, months or even years). Few observers are in a position to take such an overview of long-term participatory projects” (p. 6). As a socially engaged artist I agreed with Bishop and decided to structure my research so that I could gain a long-term and social perspective of the ways artists and museums work together.

In late 2017 I developed an ethnographic case study research design with the guidance of my dissertation advisors. Unlike art critical methodologies, ethnography prioritizes the in-situ grasp of a culture or community over time, largely through observational and discursive methods. As Marcus and Myers (1995) assert, unlike most artistic discourse, ethnography is not concerned with defining or critiquing what art is, because it is focused on “understanding how these practices are put to work in producing culture” (p. 10). I postulated that ethnography would allow me to follow the full lifecycle of socially engaged art projects from preliminary discussions, through to post-project debriefing, thereby offering the potential for new insights into gallery and artist collaborative processes. I was drawn to the ethnographic emphasis on remaining open as possible during research so that unexpected themes, unspoken participant beliefs, and/or non-obvious factors influencing a particular social situation might become visible. For example, at my first research site I realized that the backdoor to the gallery (which led into the staff offices) was commonly used by the public because the organization was open to their community stopping in any time to make use of the institution’s resources—something I may not have realized unless I jotted down how everyone entered the space. Part of what I hoped this type of ethnographic observation might offer me was a more objective perspective on socially engaged art. Like many people who work in participatory art, I get deeply invested in my projects and the people I work with, making it hard for me to separate my emotional, critical, and personal perspectives when describing my artworks to others. I theorized that taking on the role of an ethnographer might create some productive distance between me and the socially engaged art projects I was learning about so that I could get a fresh perspective on institutional and artist collaborations.

My ethnographic research design required me to temporarily relocate to the cities where the projects I was studying took place. When I arrived at my second site in January 2018, I brought with me my nine-month old rescue dog Sprout who my partner and I had acquired three months prior. Though adorable, Sprout was a high energy puppy who had learned a multitude of bad dog behaviors in the few months she lived in an overcrowded Ohio animal shelter.

Each day, before I arrived at the museum to work with the artists on their project, I took Sprout out for at least a one hour walk, during which I tried to teach her how to not pull on a leash, chase squirrels, bark at people, or eat garbage. I could then leave her for a maximum of five hours before I needed to return home and take her out for another hour or hour and a half, often in the pouring winter rains of the Pacific Northwest. Sprout frolicked around me licking my feet and trying to jump onto forbidden surfaces as I typed up my field notes each day. She sat beside me on the couch as I used one hand to edit images for the project, the other to pet her head. Sprout ripped up toys and fancy treats in the bathroom while I conducted Skype interviews. Occasionally, she would sleep beside me while I read over my notes. Other than my research, the only thing I accomplished in that two-month period was to teach Sprout how to play fetch in order to more effectively tire her out. To say dogs were on my mind during my research is an understatement; my puppy training brain was liking a weather vane, oscillating towards any canine who crossed my path, likely with the subconscious hope that I might discover how to better control my dog.

For all intents and purposes, Sprout, like the dogs in my field notes, has nothing to do with my research. She will not be mentioned in my dissertation, nor are any other canines discussed analytically in my work. And yet, their presence in my notes offers perhaps the best window into the limitations of both ethnography as a method for studying socially engaged art and of socially engaged art storytelling. Ethnographic case study, like socially engaged art, is something which unfolds over time via the mutual participation of people in a specific context. Both are fields made up of lots of participants who come to a project for different reasons, with different intentions, aims, and feelings. Any or all of someone’s life situation may be expressed or not, in action or words, at any point during a project. The challenge to articulate a socially engaged art work, be it by artists, the institutions who support them, or a researcher, will always reflect the plentitude of perspectives that the author inhabits.

Though I entered this project with the belief that ethnographic case study might provide me a more judicial viewpoint of socially engaged art, instead it reminded me of the impossibility of crafting a singular ‘accurate’ story of any socially engaged art project by highlighting how my dog/life balance was shaping my research. While ethnography offered me an innovative toolkit for approaching socially engaged art, it was not a magical periscope that stopped my life or feelings from shaping my encounter with the project. Rather than viewing the impacts that social, emotional, political, and personal experiences have on socially engaged art as a potential limitation to how we tell the stories of projects, I believe artists, galleries, and researchers simply need to be more transparent about these factors, both during the execution of a work and in its dissemination. This honesty and vulnerability, whether it is about a poorly conceived timeline, a longstanding friendship between a curator and artist, or a fixation on dogs, will help foster more inclusive dialogues about socially engaged art and will support our field in continuing to grow in new and exciting directions.

References

Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial hells: Participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. London: Verso Books.

Delamont, S. (2008). For lust of knowing: Observation in educational ethnography. In G. Walford (Ed.), How to do Educational Ethnography (Ethnography and Education) (pp. 39–56). London: Tufnell Press.

Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Marcus, G. E., & Myers, F. (1995). The traffic in culture: Refiguring art and anthropology. (G. E. Marcus & F. Myers, Eds.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Our Daughter, the Artist

Text by Hue Boey Kuek with input from Say Cheong Ng

To get the long view of an artists career and work, we asked the parents of Xi Jie Ng to offer us some insights. Xi Jie offers an introduction, and questions were prepared by Spencer Byrne-Seres.

I once shouted at my father through sobs on our porch, “Trying to live your dreams is the most practical thing you can

do in life!” and told him to read his Dalai Lama book on happiness. Two years before that, my father demanded to know my “plan b and c” when I quit my arts administration job to be an artist. Today, external institu- tional validation and experiencing my and my peers’ work have helped my parents bet- ter understand their eccentric firstborn and what it means to have a creative practice. I think they choose to see a certain side of my work in a somewhat do-gooding light; that is grand progress for us. Say Cheong is known to be an enthusiastic, task-oriented eager-beaver; he once went up to my high school theatre studies teacher and told him, “I’m worried about her. She’s coming up with weird names for herself.” Hue Boey is a hardworking, empathetic worrier-type; she encouraged my childhood love for crafts, drama and reading. Both grew up poor in developing Singapore, are now financial- ly worry-free and have never changed their civil service jobs. Putting myself in their shoes with a lot of grace (as is often need- ed in familial interactions), I see how it is terrifying that my work may challenge state control and that my life might manifest in patchwork ways wildly different from the safe, hammered-into-the-cultural-psyche Singaporean standard. But which child doesn’t yearn for profound understanding, acceptance and support (in that order) from their parents? I think a lot about karma and why we are born to our parents. Recently, my mother told me I am resourceful and suited to this crumbling world, that as a result of me, she and my father experience things they usually do not. This can mean putting on a new lens – as she wrote, to my infinite delight, “Many of the things we do, even in everyday live, is art, for example, cooking a dish, arranging furniture or deco- rating our house, gardening, sewing, writing, etc.” I am deeply grateful for their sup- port through confusion, and that my artistic practice is now, for us together, a portal into my cosmos and many more worlds that may rightly excite, shock and abhor them as they age.

-Xi Jie Ng

When did you know your daughter was going to be an artist? What were the signs? How did you feel, knowing this was her chosen path?

Xi Jie had shown a lot of creativity since young. She also enjoyed activities like drawing, art & craft and speech and drama classes. Birthday presents for some family members were always very interesting creations of hers. When she started pursuing theatre studies in junior college, that was the start of more serious pursuit of her interest in creative work. She surprised us by her projects which were out of the ordinary. After graduation, she took on a job in the National Arts Council where she organised the first silver arts festivals (for seniors) in Singapore. Her ideas of getting seniors to appreciate and participate in creative activities were very novel. She also embarked on projects like filming which showed her other talents. She went on to do other projects. We saw that there was no limit to what she is capable of and there was no doubt she would continue to pursue her interest in the arts.

We were at first a bit concerned that she was not taking the conventional path like other kids. We felt that it was a waste of her talents – she was good in both the arts and sciences subjects, including mathematics. She is intelligent and we were sure she could excel in the more conventional route. Like many parents who would like their children to have a secured future, we were concerned if she could make a living being an artist. Despite our reservations, we continue to support her.

How are artists viewed in Singapore in general?

Our sense is that there is greater understanding and appreciation of artists and their work in Singapore especially by the younger population and post-baby boomers given they are mostly educated and also more exposed to art through today’s very borderless world and greater appreciation of things beyond the science of things and materialistic pursuits.

How would you describe Xi Jie’s work? What type of artist is she? How is her work different or unique from other artists?

As amateurs in the field of art, we think that Xi Jie’s works is very varied. This reflects her multi-talents and versatility. Her work covers drawing, illustrations, writing, producing films, acting, photography, installations, etc.

What stands out about some of Xi Jie’s work is that they seem to originate from her interest in people and things of the past. For instance, capturing the daily lives of her grandmothers in film, telling the story behind Singapore’s pioneer busker in film, an exhibition on bunions which is a body defect affecting many people, getting seniors to go beyond their limits to come up with creative art and craft, working with prisoners on art projects, etc.

Some of her work is abstract and we could not immediately grasp the message behind them. Examples include her work at a few residency programmes. One of these is a picture of her against the moon that she took at a residency in Finland. Another is a project she did in Elsewhere (North Carolina) where she created a space like a Japanese capsule hotel.

How does watching Xi Jie’s work make you feel?

Xi Jie’s works have opened our eyes and at times make us feel that she lives in a different world from what we are used to. Our background is in engineering and science and our thinking is very black-and-white. We have been prepared to enter her world and experience it. Our visit to Portland in 2017 had given us the opportunity to experience her projects which we were amazed with.

What have you learned from Xi Jie’s work? Has Xi Jie’s work challenged you, or changed your views on anything?

Needless to say, it has challenged us to be very open to artistic work and to appreciate that the work has meaning to the artist behind it that we should never discount or even laugh at. The more abstract the work is, the more we have to challenge ourselves.

We learnt from Xi Jie’s work about limitless imagination, of making connections with things, people and between them and seeing meaning beyond what our eyes and our mind typically tell us. We also learnt that there is innate potential of artistic work in everyone. Many of the things we do, even in everyday live, is art, for example, cooking a dish, arranging furniture or decorating our house, gardening, sewing, writing, etc.

What is your favorite project that Xi Jie has created? Describe the project and how you engaged with it – were you a participant, saw it at an event, saw documentation (photos and videos taken of the project) ?

Our favourite project is the short film about the daily lives of her grandmothers. We are delighted that she takes an interest in how her grandmothers are spending their silver years and wants to document it in a film. The film also gives audience a glimpse into the lives of the ordinary grandmother in Singapore.

We were not involved in the filming but got updates from her. The grandmothers were as expected, accommodating. We are sure that Xi Jie learnt something more about her grandmothers through the project, for example, her maternal grandmother attended dancing class.

What is one project or artwork you wish Xi Jie would do, that she hasn’t done?

Her father hopes that she can do a project to get the community’s support for creative art for seniors. The Silver Art Festival was a good start and it is now an annual event. WIth an aging population, there are opportunities to engage more seniors in art activities that they can enjoy.

Tethers

Text by Elissa Favero