I’m Curious About You?

December 12, 2021

Text by Justin Maxon with Desire Grover and H. “Herukhuti” Sharif Williams PhD

“Racism is such a sham. It’s not what we naturally do. It’s what systems empower us to be able to do.”

DESIRE GROVER

This interview, conducted over the phone, is a collaboration between H. “Herukhuti” Sharif Williams, Desire Grover, and me. During the Fall 2021 interview for SoFA, Desire asked me a question that we chose to leave unanswered until we had the space, but it certainly needed to be answered. This interview is a follow up on that previous conversation, where Desire gets the opportunity to interview me.

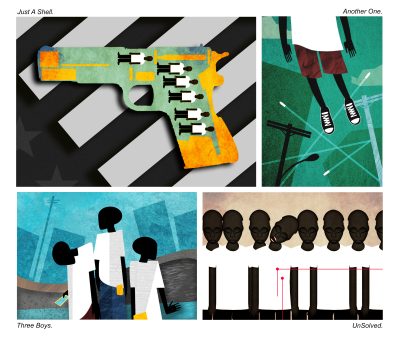

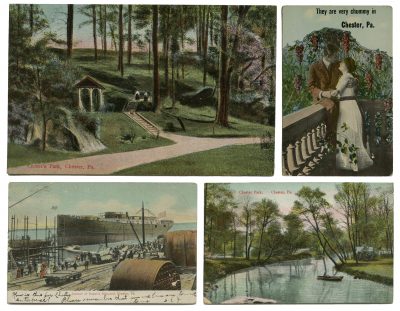

This series of interviews is a part of an ongoing dialogue and serves as an entry point into a project Williams, Grover, and myself have been developing since 2017: a collaborative book project titled Chester: Staring Down the White Gaze. At the epicenter of this critical collaboration are two sets of images: the work I completed as a photographer and journalist, covering the city of Chester, Pennsylvania from 2008-2016, and photographs from my childhood archives. Using the latter, we built a visual glossary of white racial tropes to unpack my relationship to whiteness. We use this framework to reconsider my work in Chester, along with other contemporary and historical local media coverage of the city, to elucidate the ways the white gaze reflects its own values when reflected off of the bodies of Black people.

Chester: Staring Down the White Gaze will be published as a collaborative book project of co-authors from the city who tell their own narratives: Desire Grover, illustrator; Wydeen Ringgold, citizen journalist; Leon Paterson, self-taught photographer; and Jonathan King, activist and educator. Throughout the pages of the book, the co-authors are in conversation with me about my images through handwritten text that analyzes, critiques, questions, contextualizes, and interprets the nature of the white gaze that is placed on their community.

Desire Grover: Actually, I’m curious about you. I’m curious what it is that you were looking for when you decided to come to Chester with your camera? Why couldn’t you just go in your own community? And have you gone into your own community with the same expectations? What were those expectations about Chester that are not the same for your own personal community, where you grew up?

Justin Maxon: I came to Chester for two main reasons: I honestly didn’t see myself as white as other white people, and I was seeking connection with my camera. Which is ironic because photography is all about control right? How can you have connection with an undercurrent of control? That’s how whiteness seeps into play. This contradiction was pressed upon me being a white son to a white father. I learned connection through my own historic trauma being a white person. My subconscious thought that the camera would lead me to connection. The reason I was looking for it in Chester ties into the fact that growing up, I never felt I had “my own” community growing up in Humboldt County, CA.

Desire: Hmm.

Justin: My father lived on the Hoopa Valley Indian Reservation my whole childhood, and my mother lived in Eureka, CA. My time was split between the two places. So, I never felt settled in one place. Growing up on the reservation as a person racialized as white, I was always reminded that I wasn’t part of this space. I wasn’t part of this community. Eventually, that became familiar. The things we seek out as adults in many ways are recreations of the dynamics at play in our childhood.

Desire: Not to throw you off or anything, but I’m kind of curious – in a nutshell, are you saying that pretty much you saw yourself as experiencing on some level what it meant to be other?

Justin: Yes, problematically so. It’s the cool white boy, right? He is the white boy who takes on the traits of BIPOC folks.

Desire: My man.

Justin: Exactly, they extract Black aesthetics from Black culture. When white people feel like they don’t belong in the fold of whiteness – when they’re on the fringes – we have the sensation of what it feels like to be the other. I never felt accepted. I didn’t grow up with family on both sides. It was me, my mother, and father. They both moved away from their families.

Desire: Did you interact with the community there?

Justin: Definitely. Just some context to my living conditions there: my father was extremely poor. We lived in abject poverty. He was disabled, obese, and had a serious mental illness. He slept all day, like he was literally in bed all day. And so, I just did whatever I wanted. I had a handful of friends that were my age that were indigenous and we just did whatever we wanted. They’re familial experiences were similar to mine. We didn’t have parental supervision growing up. My whiteness was reflected back on me. People saw me as the white kid that hung out with Carlie [my best friend growing up in Hoopa]. It just became accepted, like what happened in Chester.

Desire: For you, that seems familiar, you just gravitate to it. It’s your norm. It’s just water, yes?

Justin: Yes, exactly.

Desire: Yeah, it’s how we cope.

As social animals, what we do to accommodate our needs for acceptance and community engagement is nature. It’s not natural for anyone to not want to engage another human being. It’s deeply a part of what we are as humans. To me there are these little funny moments, where I feel like we’re not even talking as much about race as we’re talking about the need to be accepted, the need to have community. Certain cultural norms can either hinder that or help that.

Justin: That makes sense.

Desire: I believe that racism is a privilege. And the reason I refer to it as a privilege is because it is something someone can do when they think they can afford it.

Justin: That makes complete sense.

Desire: Right, for example, when you think about what happens to some of these bigots who go out in public and do crazy things right, and they start crying as soon as there’s backlash. They start falling apart. You just get blown away like, Wow, they were so full of arrogance just five minutes ago. That act of shunning is very powerful. Either they double down even harder because it’s hit them so hard or they completely flip the other way. To be shunned is not a simple thing; it’s not a little thing [for us] as human beings.

I noticed in my life so many people who have been bigoted that I’ve had to engage with, oftentimes would not give me eye contact.

Justin: The connection, they feel like they don’t need it?

Desire: Two things I feel like are happening. One, they don’t want me to be human, so they can’t look me in the eye. That would mean they might see humanity and then it makes them feel some kind of way. Or, secondly, the power of robbing me of that connection is what they’re utilizing in that moment. I can steal from you the acknowledgment of your humanity.

Justin: At the same time they’re robbing themselves of their own.

Desire: Right, right.

Justin: The reason why they can’t afford to do that is because they have this perception, right.

Desire: Yeah, they think they have this endless support system.

What happens when that same bigoted man is in Nigeria and is looking for someone to relate to? He hears my voice speaking with an American accent, and gets excited because someone speaks English in a way that is familiar [laugh].

Racism is such a sham. It’s not what we naturally do. It’s what systems empower us to be able to do. Even now, this whole lie about the election, they’re seeing there’s a power dynamic shifting, so they have to build up another foundation to keep things status quo. We’re not going to go by these rules anymore. You know how kids do in the sandbox? They play in a game, and then the one starts losing and then they destroy the whole game. Now nobody can play! That’s pretty much what is happening right before our eyes.

I insist that racism is a privilege and a lot of people who exercise racism wouldn’t dare if they were in that minority position.

Justin: Exactly. I think what we are talking about is more connected to conservative white America, who feels like they have that wealth of connection in their own white space, so they don’t need to acknowledge someone else’s humanity. Circling back to my own experience with racism, i.e. my desire for connection. For white liberals that grew up, such as me, disconnected from white spaces, they feel like they have to find connection to humanity in whatever space they are in. Because I had that proximity to a BIPOC space, I felt like some part of me belonged in a non-white space. That I could work in a BIPOC space as a professional. That I could operate with the mechanisms of power in a BIPOC space in a way that was useful. When I went into Chester, I honestly thought that I was being useful. Obviously, that screams white savior. Because the criticality of whiteness wasn’t part of my education, it wasn’t part of my parental upbringing, I was able to cause tremendous harm because of my comfortability within BIPOC spaces. Harm that conservative white America could never cause because of a lack of proximity. This is something I’ve read, that white liberal folks cause the most harm to the bodies of BIPOC folks on a daily basis.

Desire: I find it fascinating how often my liberal white friends, or acquaintances, more so, have a tendency to carry a lot of the same assumptions as the so-called conservative. But they’re not honest about it, they wait until they’re in crisis, and then it comes out. It can be very dangerous. [In my graduate program] we were just reading Audrey Lorde, Sister Outsider, and there’s a part where she’s talking to a fellow colleague, a white woman in the feminist movement, who uses her words without consent and within this bizarre context that puts Black women in this negative light. Well, long story short, we ended up having a discussion as to why Audrey would embarrass this woman in front of everyone – not initially, she tried to have a private conversation with her, but she didn’t get any real engagement from her colleague. I was the only Black person in class [laughs]. I was just like, Oh, here we go. It is not uncommon for white people who regard themselves as my friend, and so on, to end up failing when it counts. Black people are so used to that. Like when you were talking about [how] there’s a certain kind of social living that you were used to, and you kept trying to recreate that, right? There’s a certain level of low expectation that I must have or I will be devastated way too often. It’s to the point where certain scenarios have happened, and I’ve been able to predict the outcome. Oh, ok, this move they’re going to be this defensive, they’re going to stonewall me here, they’re going to do this number. It all plays out, because the truth is, it’s very difficult for folks to know who they are until they’re in crisis.

The work you’re doing to yourself is so exceptional, so uncommon, that on some level it kind of scares me.

Justin: It’s scary because of how elastic whiteness is. So, even in this context of me confronting myself, whiteness can still rise to the top. Best selling author Robin DiAngelo is a prime example. DiAngelo confronted herself and now she’s getting paid tens of thousands of dollars to go and lecture for an hour. So, this criticality is now a commodity good to be bought and sold.

Desire: Audrey Lorde talks about how there’s certain conversations that only white people can have with white people. I do think there is a certain level of conversation that I just can’t have. It is dangerous for me. People are rejecting your lived experience. Oftentimes, I don’t feel like I get to have the conversation I want to have and then that compounds the trauma. They’re responding to someone who is not like them in their minds. So, this conversation really is supposed to be between white people and white people.

Justin: Maybe we shouldn’t have this conversation now?

Desire: [Laughs]

Justin: I was just trying to honor what you just said. Forcing you to have this conversation would be the last thing I wanted to do.

Desire: No, no, I totally agreed to it. I actually instigated the conversation because I wanted to finish it. I feel like we have conversations that I definitely want to have.

When it comes to the population at large and how white people respond, really there’s nothing that a non-white person, I think, can say or do, as powerful and dynamic as hearing it from another white person.

Justin: Which is unfortunate.

Desire: Is that unfortunate or is that just how humans respond? Like there’s certain conversations you can’t have with Black people, Justin. It’s just not happening. You can try and then end up with eggs and tomatoes. You could even say exactly the same things I’m saying, and they could be 100% true, but it’s coming from you. There are certain conversations I can have with evangelicals because I know stuff. I know what you’re thinking, I know what the manipulation buttons are. So, they can’t play me in the conversation like they might a Catholic person. We need to be open to the leverage we have in certain communities and just have to bear the brunt.

Justin: Yeah totally. I think just for me it’s relevant to look at DiAngelo as an example, in relation to who’s labor is fairly compensated within the context of conversations around critical race theory. After many conversations with Herukhuti, he has mentioned that while working within white spaces for decades, his time and energy has never been compensated fairly. So, for a person like Robin DiAngelo to be made a celebrity overnight, it’s bypassing the labor of BIPOC scholars and thinkers. This is certainly a trap of whiteness that I could see myself falling into. If I am gaining social capital from this work, how am I distributing that?

Desire: So, in what way is Robin on some levels substantively impacting the conversation of race beyond becoming a guru of some kind? Yeah, that’s always tricky business and I’ve heard this word “grifting” being used a lot more. Man, capitalism don’t give any fucks. It will manipulate anything, and nothing is sacred.

I used to be a very anti-platform person. I just hate the idea of being that front person. I grew up as a preacher’s kid, so giving praise to somebody just because of the position they are in is weird. I hate it, so I understand the aversion, but at the same time, there is a role that someone has to fill. If nobody’s filling that space we’re going to have compounded problems. We will reward someone to the point where they become useless. That’s how the platforms are; they try to over expose you so you’re the only voice they will tolerate.

Justin: Yeah, that’s it! That’s how whiteness slips through. If there’s only a singular voice allowed to speak, it doesn’t become something that’s on everybody’s tongue.

Desire: Exactly. These Messiahs they put out, oh, they’re allowed to dissent. They do that to comedians. We gotta laugh at all of it. Let’s laugh. Haha. They are so wise, let’s laugh with them. Then you just go home and do nothing with it, because you laughed it all out.

One of the tactics the police would do when we would do sit-ins, they wouldn’t come in with force. They have these police officers that are more well trained than the ones you have on the street. And they played little mind games with you. Say if you are in a group obstructing traffic, they’ll send police officers, but they don’t look like police officers and they don’t talk like police officers. They actually will listen to your concerns and go, “Ohhh, okay.” They’ll let you just talk it out, talk and talk it out and by the time people are done all their frustrations are down because they’ve had this conversation. And then they’re able to pick you off one by one, away from the line. Like, “We want to just talk to you, do you really think the others should be here? Because we can set up a meeting…” They do it more so in places like Harrisburg and [Washington] DC, the closer you are to the politicians. If you are out and on the block, they’re just gonna tear gas your face.

Oftentimes we are given these Messiahs that can talk about it, and because it’s being said, we think it is being taken care of.

Justin: That’s interesting psychology, I never even thought about that.

Desire: It’s a game. Human beings wanted an excuse not to do anything. Ah, I just want my latte. Cheeseburgers and fries right now, can we not deal with this? But now the Internet has made it dangerous. Now you have these weird wanna-be prophets everywhere. They’re in people’s heads all the time. On a loop. YouTube will loop the same video over if you let it.

I find it intriguing, where you, as a young white man, put yourself in the position of the other. I find that to be a fascinating thing, because most human beings don’t want to be the Other. They don’t want to be the odd one out. You know, they just want to fit in, be normal. I would be curious about that beyond just the issue of race? There has to be another narrative unfolding?

Justin: I was most certainly an outsider in any context I was in. I was disempowered my whole childhood. I was shunned deeply because of how I embodied my masculinity. My failure to meet the criteria of my outward appearing gender identity was dangerous for me. I grew up drowning in hypermasculinity. I was terrorized every day of my adolescence; I had ten bullies, and one was in my home. There was no escape. I never felt I could be myself. In subsequent years, I came to realize Oh, I’m not straight, and Oh, I can express my gender in a way that’s not so binary, and it’s acceptable.

But again, we are talking about proximity again, right? When you look at the intersection of power and privilege, I don’t think you can get any more dangerous than my childhood. As as white person, with a disempowered youth, who learned how to pass at being cis and straight to survive, even though I’m neither, I have forward access to the mechanisms of power. I caused harm without recognizing it because of this intersection within my identity.

Desire: What did it take for you to even realize you had power and why? You’re someone who was bullied, and I would imagine there was a period of your life where you didn’t feel you had power.

Justin: I think the camera. I started to come into my power when I had a camera in my hand regularly. I started to see myself as being worthy of my humanity. I still cling now to it, as an almost 40 year old man, the validation that comes through the things that I do with my camera. I rely on it more than the validation that comes from the human being I am. Becoming a photographer didn’t happen overnight. It took me many years before I could just go up to anyone and talk to them. Eventually when it became second nature, that’s when I was like Oh, I’m strong. I can go and put myself in any space that I have the courage to. That is extreme privilege. At the time, I saw it as more personal power; Oh look, I’m overcoming the limitations of my childhood. I’m overcoming the traumas of my adolescence.

Desire: The camera was a kind of a force field.

Justin: Exactly. It makes sense that it would be the thing that I would use to cause the greatest harm right. This makes me think about the way in which white people can cause harm; their greatest accomplishment causes the greatest harm.

Desire: The camera is a powerful tool. It brings a vulnerability out of perfect strangers and it gives context to why you are there. You’re the camera person.

Justin: What is so troubling is that I was there for that reason. People in Chester would call me up and I would photograph countless parties, birthdays, and weddings. I would print out the pictures for free. But, at the same time, I was working on my own “project,” for a white audience that wanted to hear what I had to say. So, on the one hand, there was this genuine generosity, which allowed me the access, but there was this deep harm that was also happening at the same time.

Desire: Because you were responding to what you thought that audience wanted to see? You weren’t going against the grain of their expectation.

Justin: The audience that I was speaking to were not interested in the snapshots of people’s lives. They wanted the drama.

Desire: The Black death.

Justin: Yes, exactly.

Desire: I wonder what else are we willing to let happen on camera?

Justin Maxon (he/him) is an award-winning visual journalist, arts educator, and aspiring social practice artist. His work takes an interdisciplinary approach that acknowledges the socio-historical context from which issues are born and incorporates multiple voices that texture stories. He seeks to understand how positionally plays out in his work as a storyteller. He has received numerous awards for his photography and video projects. He was a teaching artist in a US State Department-sponsored cultural exchange program between the United States and South Africa. He has worked on feature stories for publications such as TIME, Rolling Stone, the New Yorker, Mother Jones, and NPR.

Desire Grover (she/her) studied digital illustration & design at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. She’s been an illustrator for 18 years. She illustrated the four-book series called Hey L’il D by Bob Lanier. Over the years she has done art workshops for her community. She published her first children’s book, For the Love of Peanut Butter, and is currently working on a graphic novel called, The Fatherless Messiah.

H. “Herukhuti” Sharif Williams PhD (he/him), is the founder and chief erotics officer of the Center for Culture, Sexuality, and Spirituality. He is a playwright, stage director, documentary filmmaker, and performance artist. Dr. Herukhuti is the award-winning author of the experimental text, Conjuring Black Funk: Notes on Culture, Sexuality, and Spirituality, Volume 1 and co-editor of the Lambda Literary Award nonfiction finalist anthology and Bisexual Book Awards nonfiction and anthology winner, Recognize: The Voices of Bisexual Men. Dr. Herukhuti is a core faculty member in the BFA in Socially Engaged Art, co-founder and core faculty member in the Sexuality Studies undergraduate concentration at Goddard College, and adjunct associate professor of Applied Theatre Research in the School of Professional studies at the City University of New York.