Learning to Participate

May 30, 2018

Text by Roz Crews

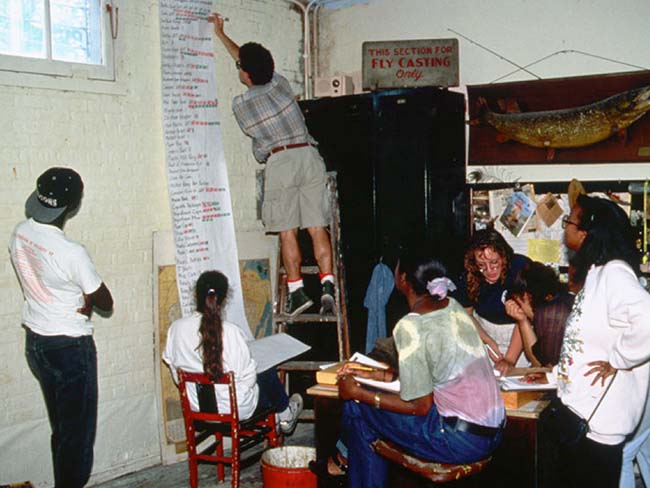

In August 2017, I founded the Center for Undisciplined Research, a nine-month art project situated within the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. The Center was meant to be a place for interdisciplinary research related to students’ interests. In the beginning of the school year, the incoming class of first year students collectively selected four main research topics: social justice, sustainability, music, and local cultures. Originally, I envisioned a structure for the project based on a traditional university center where the emphasis is on providing students and faculty with opportunities to practice interdisciplinary research and public engagement. As the year progressed, I realized that we didn’t exactly research any particular topic as much as we experimented with various ways to do and present “learning”; we functioned more often as a community of learners rather than a group of students with a “teacher.” Through the process, the collective established a force outside of the academic classroom where people came together to learn and practice new things publicly—maybe we became our own kind of citizenry within the university. Through this work, I am interested in breaking down the distinction between curricular and extra-curricular time to focus on what it means to be a participant within a community.

Since January 2015, I’ve lived in two different university residence halls as an Artist in Residence, where I’ve been working with first year students to think about how art relates to civic engagement. The intensity of my live-work situations has emphasized the relationship I see between education and civics—living my entire life between the walls of academic institutions surrounded by systems like: student and faculty governments; sexist, racist, ableist, and classist policies and procedures; the notion and consequences of tenure; controlled “common spaces”; false public space; condescending colleagues; outrageous tuition and crippling debt; lack of opportunity and resources; freedom of speech; depoliticized classrooms; and other civic structures upholding the current state of “higher education.” I’ve come to see my art practice as a tool for considering how and in what ways a university does or does not support the development of “engaged citizens.”

In the Reggio Emilia approach to childhood education, teachers document each student’s experience and progression using photography, note-taking, drawing, video and sound. I’ve incorporated this practice and other aspects of the Reggio Emilia approach into my work at the college level. This approach, in combination with the work of theorists like bell hooks and Paulo Freire, have helped me manifest my belief that students must work in collaboration with the teacher to create an atmosphere conducive to critical thinking and learning. Additionally, I’ve been influenced by practitioners of the Socratic method, archives from places like the Highlander Folk School (now known as the Highlander Research and Education Center) and Black Mountain College, as well as aspects of my own public education including my time at New College of Florida, my experience in the Art and Social Practice MFA program at Portland State University, and most especially, my committed teachers who’ve demonstrated the interwoven relationship between school, art, and life.

For this piece, I’ve recounted eight specific moments throughout my own education which call attention to the relationship between education, art, and civic life. I think this set of descriptions function together to explain how I arrived at the decision to make space for the Center for Undisciplined Research—a self-governing body of dedicated individuals, organizations, and teams that came together to explore the gray spaces between curricular and extra-curricular activities within a university community. I’m thinking about these moments as key memories that inspired me to think more deeply about how sites for education function as spaces where people decide how they want to engage with other members of their society. As you read through this essay, please consider the following quote from the exhibition catalogue written by Helen Molesworth, Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957 because I think it sort of sets a framework for where my mind is:

“Paul Goodman contends that when institutions and social roles become more important than the people who constitute them, humanity is suppressed to befit the system. Individuals must, therefore, disrupt the system to regain their humanity.” 1

1

When my painting professor told me there were no interdisciplinary MFA programs. 2008.

I’m not sure if my painting professor actually said this or if this is just what I heard as an obstinate twenty year old, determined to forge my own path. Regardless, this moment sticks with me because almost immediately after hearing her, I found out there are lots of interdisciplinary MFA programs out there. This interaction taught me to question the status quo and to seek out the information that I want to be true. It propelled me away from majoring in art, and it encouraged me to see what other interests I could pursue. During this conversation, my painting professor suggested that I check out a book from the library about Mark Dion—from her perspective, he was one of the only artists working in a truly interdisciplinary way at the time.

I remember seeing an image of Mark’s piece “On Tropical Nature” (1991), and I immediately felt connected to the varied “languages” present in the work. Within the project, I saw symbols and strategies from all the fields I was thinking about at the time—environmental science, archaeology and anthropology, art, ecology, and sociology. About eight years later I learned about his project, “Urban Ecology Action Group” (1993) during which he assembled a team from a local high school in Chicago to create a center for studying the ecology of a Chicago park, and I felt similarly transformed. Reading about this piece gave me a kind of hope that I could make work that was in conversation with other disciplines while continuing to be an artist.

On Tropical Nature, 1991. Source: http://www.tanyabonakdargallery.com/artists/mark-dion/series-sculpture-and-installation/41

2

When I spent two weeks at Mildred’s Lane. 2015.

After knowing about Mark’s work for several years, I eventually had an opportunity to

visit one of the largest and most collaborative installation’s he’s been involved with—Mildred’s Lane—which he and J. Morgan Puett founded in 1996.

The main house at Mildred’s Lane, 2015. Photo courtesy of the author. From

the project’s website accessed on May 10, 2018: Mildred’s Lane is a 96-acre site deep in the

woods of rural northeastern Pennsylvania bordering Narrowsburg, New York. It is a working

living-researching experiment centered on domesticity. The entire site is an art complex(ity)

open to anyone interested in programs and events that creatively embrace every aspect of life

in the 21st century.

I went there to attend a two-week workshop about social practice and walking as art which was co-taught by Dillon De Give and Harrell Fletcher, and during the trip, I felt like I was living in an installation. Being there was magical and it felt partly like summer camp, partly like school, partly like a party from the late 1800s, and partly like a long sleep-over. I was overwhelmed by the various ways I learned while I was there. Reading, walking, socializing, cooking, cleaning, organizing, talking, acting, public speaking, listening, swimming, and sitting quietly as learning. This was one of the first times I thought critically about how experiential education can unfold. The place and the pedagogy both feel inspired by Black Mountain College (as are many of the institutional educational experiences I’ve had).

Below is a description of Black Mountain College that feels especially relevant to my time at Mildred’s Lane:

“The mutability between art and entertainment, between work and play, was essential, not only because the mission of progressive education was to train democratic citizens capable of ‘the pursuit of happiness’ but also because it allowed for shifting positions between artist and audience. This fluidity suggested that making art was not an isolated activity, nor was membership in an audience a permanent condition. Rather the move between the two positions (actor and audience) was constitutive of the social fabric in which members have equal and rotating obligations to one another.” 2

Photo students at Black Mountain College. Source: https:/

www.thenation.com/article/the-weirdness-and-joy-of-black-mountain-college/

Being there also showed me how empowering it can be to work together with a team of people as part of something that is called an art project—something which is truly interdisciplinary. This was the first time I got to participate in a project that considered so many other disciplines as integral to its being. And it was really inspiring to be surrounded by fascinating artists from various countries and states within the US.

I’m thinking now about how this place contributed to my understanding of civic engagement, and I remember a really important moment when I was looking for a rolling pin. I was in the kitchen baking something with two other fellows, Pallavi Sen and Adele Ball. I looked around a little bit for a rolling pin, and as I was looking, Morgan walked in the room. I asked her where the rolling pin is stored. She asked if I had already looked for it myself, and then I said, “Yes, a little bit.” She responded, “If you had really looked, you would have found it. I suggest you look some more until you find it, and if you REALLY can’t find it, then I’ll be happy to show you were it is.” She left the room. I was startled by her assertiveness, and deflated by my own meekness. Eventually I found the rolling pin. This conversation made me feel a kind of urgency I hadn’t experienced before. I felt compelled to put my best effort into tasks before relying on someone else’s resources (in this case, Morgan’s time). This was an empowering moment because I realized I could probably teach myself almost anything I wanted to know if I was willing to put in the effort. And I felt reassured that if I did seriously need help, I had a community that would support me.

3

Swimming in a pool with snakes. 2009.

Tropical Ecology with Meg Lowman was one of the most influential courses I took during my undergraduate career at New College of Florida. It was an advanced level seminar in environmental studies, and I was a first-year student obsessed with sea turtles, pop-culture, and painting. I spent part of the summer before helping to collect data about Green Sea Turtle’s nesting habits in Tortuguero, Costa Rica, so based on that experience, I felt that I had satisfied some kind of requirement that gave me permission to skip any prerequisites for the class. I asked the instructor to join the class, explaining my reasons, and she agreed to have me. Everyone else was a junior or senior with a lot of knowledge about the environment and ecology in the region and beyond. For some reason, my out-of-placeness in this scenario didn’t bother me, and I joined the class with joy and appreciation.

After a semester of exciting experiments and experiences with the local environment, our professor invited us over to her house in the suburbs of Sarasota, Florida to have an end of year party. She invited a leading invasive species specialist, Skip Snow 3, to join our class for the event. He brought several animals with him to demonstrate some of the ways that exotic pets invade and destroy the local ecosystem after they are abandoned by their owners. As part of the demonstration, giant pythons were released into the fenced-in backyard pool area, and we were invited to swim with them. There was also a cake with snakes painted in frosting. I remember feeling totally amazed by Skip and his snakes. The experience was unlike anything I had ever done before—it was basically a pool party with invasive species masquerading as a college class. A lot of the folks who were in that class went on to become experts in various ecological topics, and even though I didn’t do that, the course taught me how to value experience as education.

4

Interviewing a stranger about their clothes. 2014.

When I applied to graduate school, one of the application requirements was to make a video of yourself asking a stranger about their clothes. As a lover of strangers and fashion, I had talked to plenty of strangers about their clothes in the past, but I had never documented any of those conversations through video. For the application, I decided to visit City Liquidators, self-described as “ample headquarters featuring an extensive selection of discount furniture plus home decor,” 4 in southeast Portland because I had been there a few times to buy props for work 5 and I was impressed by the sheer amount of objects filling the shelves. Without a doubt, I would meet someone interesting. I ended up talking to the owner’s wife who suggested that I talk to her husband because he had a reputation as a connoisseur of crazy socks. I spent an hour or so with the couple and their dogs in the back office. It was a really pleasant experience that was much more in-depth than any other conversation I had previously with a stranger about their clothes—a situation that would not have happened otherwise.

The process of actually doing something I might only have thought about doing if it weren’t for the assignment empowered me to dream bigger about what kinds of things I could do. It also helped me formalize the social, curious part of myself into something that I could utilize in my art practice. I started to see how my engagement with people might be interesting as part of my exploration of art. Since making that video, the process of claiming my curiosity and civic engagement as part of my work has emphasized the difference between doing something and thinking about doing something, as a motivating force.

5

Anna Craycroft’s Lecture at PNCA. 2015.

I was just starting my second year of graduate school, and I had only begun to scratch the surface of the question, “Why are you making this [artwork, book, essay, etc.]?” Anna Craycroft’s lecture at PNCA in October 2015 helped me see how an artist can create cohesive and concise projects while simultaneously being influenced by a variety of topics, experiences, and thoughts.

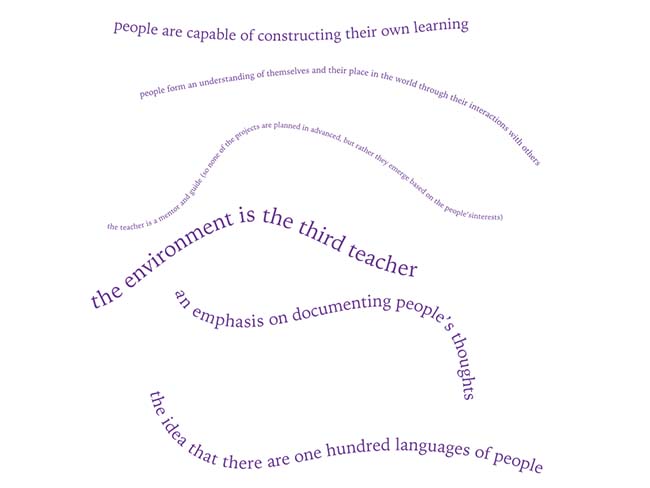

During this talk, she described some of her projects, but mainly, she explored out-loud and with images the lines of inquiry surrounding the artwork. One of the main things she discussed was the Reggio Emilia approach as it relates to a few of her projects. 6 This discussion got me thinking about how I learn, why I document my life so meticulously, and what it would mean to use the Reggio Emilia approach with adults.

Core aspects of Reggio Emilia 7 :

– Children are capable of constructing their own learning

– Children form an understanding of themselves and their place in the world through their interactions with others (social collaboration)

– The environment is the third teacher

– The adult is a mentor and guide (so none of the projects are planned in advanced, but rather they emerge based on the child’s interests)

– An emphasis on documenting children’s thoughts

– The idea that there are one hundred languages of children

When I started thinking about the fundamental principles of the Reggio Emilia approach in connection to adult education, I saw clearly the links between education and participation in society. By replacing “child” or “children” with “person” or “people,” this list of principles functions as a nice blueprint for how to make a thoughtful, empowering, and generative civic space for adults.

6

When one of my students gave a class presentation about how inadequately my co-teacher and I were conducting the course. 2016.

The first time I taught a college course, I was a co-instructor with another teacher, and we were both very dedicated to establishing a horizontal learning environment where students felt responsible for contributing to the experience of being in the class. We hoped to make our classroom a space for exchange that could happen in any direction between everyone involved. In many ways, we were working directly in contrast with a more traditional type of classroom—we were working against a style of education that Paulo Freire refers to as the “banking concept of education.” 8

One day in the beginning of the semester, there was an event during which one student expressed that my co-teacher and I were not meeting their expectations of what should happen in the class. This student seemed to believe that we should be pouring meaningful, important, and otherwise inaccessible knowledge into their brain. The student expressed a desire to be a passive consumer, dependent on an economic exchange involving money and expertise.

I like to imagine water pouring in from all different sources, seeping into the cracks and crevices, absorbing into my permeable body—but not filling me up like an empty vessel. Image: Water Pouring into Swimming Pool, Santa Monica, 1964 by David Hockney. Source: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hockney-water-pouring-into-swimming-pool-santa-monica-p11378

This experience was a great reminder that some people disagree with how I want to teach, and it encouraged me to solidify my approach and vision so that I could defend my choices thoroughly in the future. Despite the difficulty of the situation, I became even more certain that I was on the right path, and I realized how much work it takes to shift a paradigm and to change expectations in the classroom. It also made me reflect on my relationship with government and local politics—if I could think of ways to effectively shift a paradigm within the classroom, I wondered if it would be possible to effectively communicate ideas with folks who disagreed with me in a more public sphere like the Neighborhood Association or City Hall.

7

Having smoothies with bell hooks. 2012.

Four Winds Cafe at New College of Florida. Source: https://www.thoughtco.com/new-college-of-florida-photo-tour-788513

Throughout college, I worked at the Four Winds Cafe as a barista. This cafe, situated on campus, started as an economics student’s thesis project in 1996 and has continued as a student-owned and operated vegetarian restaurant and coffee shop since then. I was always inspired by the fact that a student created the cafe as a way to experiment with running a business, and I was even more excited to be at an institution where that type of project was not only allowed, but encouraged. In our life as cafe employees in the 2000s, we used it to experiment with cooking, and to host art shows, performances, lectures, special dinners, and other events. It felt like the cafe had its own civic life within the university, totally driven by students (even the director was required to be a recent graduate from New College).

Towards the end of my time at the university, bell hooks was embedded there as a visiting scholar, and she frequented the cafe. One day when I was working she asked me for a smoothie recommendation—I suggested the Bee’s Knees (almond milk, frozen blueberries, frozen bananas, honey, cinnamon, and vanilla protein powder). She tried it, and from that moment on, I felt connected to her. We often sat on the couches after my shift, just talking about life and love. We also served together on a committee of students and faculty that was organized to discuss and strategize ways to cope with the fact that there was a well-known white supremacist enrolled at New College at the time.

During this period, I fell in love with someone who was living in Oregon. I had one semester left in college, but I had all my credits and if I defended my thesis early, I could graduate early, and leave to live with my brand new lover in Oregon. Most people I talked to expressed concern about this idea—the idea of moving across the country to be with a person I only just met. But I knew how I felt, and I told bell about this situation. She encouraged me to follow my heart, so I did—almost immediately.

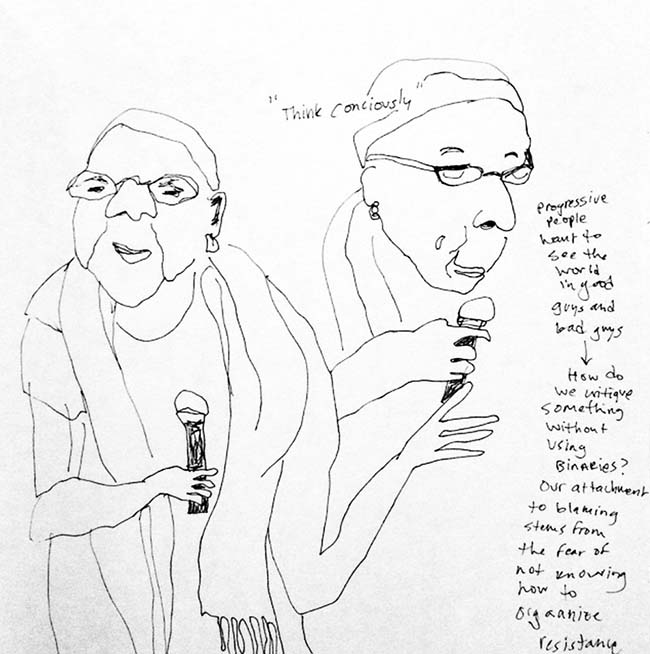

My casual experiences chatting with bell hooks showed me how influential and encouraging an academic person could be in an extracurricular way. At the time, I was an anthropology major with very little experience reading or thinking about theory, and I had never encountered bell’s work in a classroom setting. However, spending time with her made it so I could absorb some of her theoretical underpinnings into my moral fabric; our conversations made it possible for me to think about things in new ways without reading her texts. One day after knowing her for awhile, I saw her give a lecture, and I had a revelation about all the things I’d learned through talking to her. Her academic explanations gave context to my conversations with her.

Drawing by the author during one of bell hooks’ lectures at New College of Florida. Image courtesy of the author.

A few years later I started reading her books, and her texts got me thinking critically about how I facilitate learning environments—inside and outside of classroom settings. Making a productive space for education requires thinking and talking about how people engage with each other and how they make themselves accountable to the other folks in the room and beyond.

hooks has a lot of amazing things to say about the state of higher education:

“If we examine critically the traditional role of the university in the pursuit of truth and the sharing of knowledge and information, it is painfully clear that biases that uphold and maintain white supremacy, imperialism, sexism, and racism have distorted education so that it is no longer about the practice of freedom. The call for a recognition of cultural diversity, a rethinking of ways of knowing, a deconstruction of old epistemologies, and the concomitant demand that here be a transformation in our classrooms, in how we teach and what we teach, has been a necessary revolution—one that seeks to restore life to a corrupt and dying academy.” 9

Without bell hooks’ work (this particular excerpt is from 1993!), I might be afraid to acknowledge that my classrooms and the choices that I make within them are political, but because I can rely on her work and her spirit as the background for what I’m doing, I’m not scared to consciously make political decisions according to my own beliefs. Choosing to not talk about politics and social problems within a classroom context is just as political of a statement as discussing openly, so I think it’s important to be aware of what choices I’m making.

8

When Harrell asked, “How do you want to spend your time as an artist?” 2016.

Towards the end of graduate school, our professor Harrell Fletcher asked the group the question—“How do you want to spend your time as an artist?” Maybe he didn’t include “as an artist” in his original question, but that’s always how I’ve remembered it. This inquiry cracked open a lot of assumptions I had about what I might do as an artist. Suddenly I was free to spend my time anyway that I wanted, and I wasn’t bound to other methods, models, and approaches demonstrated by artists who came before me. At the same time, I could bind myself to ways of living that non-artists had established and followed for themselves. Everything felt so open, and I realized again how important it is to choose wisely and intentionally.

Right now, as an artist, I want to make time to think about how different and unique each one of these roses is. I took this photo at the Washington Park Rose Garden in Portland Oregon a few years ago, and I’m amazed looking at it now because I realize that while every flower in this picture is a rose, each one is completely different from the next. There must be hundreds of totally unique flowers here, and I want to carve out time to observe them all for their special qualities. But I’m not interested in doing this alone. I want my art practice to be a space for being together with other people, to view, to analyze, to describe the roses together—togetherness with a sense of urgency and responsibility.

I guess I hope that the civic spaces I encounter and participate in can function in an almost identical way to how I want my art practice to be. I’ve learned to inhabit shared space with a strong sense of curiosity, compassion, appreciation, and awareness—but I wasn’t born this way, I had to learn how to participate.

Footnotes:

1. Molesworth, Helen. Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957. Page 281. Yale University Press. 2015. “Leap Before You Look is a singular exploration of this legendary school and of the work of the artists who spent time there. Scholars from a variety of fields contribute original essays about diverse aspects of the College—spanning everything from its farm program to the influence of Bauhaus principles—and about the people and ideas that gave it such a lasting impact. In addition, catalogue entries highlight selected works, including writings, musical compositions, visual arts, and crafts. The book’s fresh approach and rich illustration program convey the atmosphere of creativity and experimentation that was unique to Black Mountain College, and that served as an inspiration to so many. This timely volume will be essential reading for anyone interested in the College and its enduring legacy.” This description comes from the Yale University Press website.

2. Molesworth, Helen. Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957. Page 46-47. Yale University Press. 2015.

3. Read this article to learn more about Skip Snow’s work: Revkin, Andrew C. A Movable Beast: Asian Pythons Thrive in Florida. New York Times. 2007.

4. Learn more about City Liquidators by visiting their website.

5. At the time I was working for a video production company as a producer.

6. Learn more about Anna Craycroft’s approach in this interview about her project C’mon Language with Sarah Murkett for MutualArt.com and the Huffington Post.

7. See the “main principles” of the Reggio Emilia approach here.

8. Freire, Paulo. “Chapter 2: Philosophy of Education.” Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 1968.

“In the banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing. Projecting an absolute ignorance onto others, a characteristic of the ideology of oppression, negates education and knowledge as processes of inquiry. The teacher presents himself to his students as their necessary opposite; by considering their ignorance absolute, he justifies his own existence. The students, alienated like the slave in the Hegelian dialectic, accept their ignorance as justifying the teachers existence—but unlike the slave, they never discover that they educate the teacher.”

9. hooks, bell. “A Revolution of Values: The Promise of Multicultural Change.” Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Page 30. Routledge. 1993.

Roz Crews is currently the artist in residence at the Working Library, a program of c3:initiative in Portland, Oregon where she is creating a temporary event space called the Conceptual Drawing Studio. During the 2017-2018 school year, she was the artist in residence at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth where she founded and directed the Center for Undisciplined Research, a nine-month public artwork and student-focused research collective sited on campus as a tool for people to critically examine what and how they want to learn. She makes collaborative and participatory projects which manifest in a variety of forms including videos, installations, publications, performances, ephemeral structures, and workshops. She wants to know where learning happens, and she uses her art practice as a platform to fnd out more about how art schools prepare artists (and more generally, how schools function to “train” citizens), ways to disrupt systems, and how people participate in society. She was the Artist in Residence at Portland State University’s Housing and Residence Life Department (2014-2017), a curatorial assistant at the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art (2015-2017), and she is a co-curator of the King School Museum of Contemporary Art’s annual International Art Fair as part of Converge 45 in Portland, Oregon (2017). She holds an MFA from Portland State University’s Art & Social Practice program, and a BA in Public Archaeology from New College of Florida.