Much Love to You Dearest Gilian

December 5, 2023

Text by Gilian Rappaport with Violet Baxtor

“I looked closely into the bushes in front of me, locating the patterns of the leaves, and into the racing rivers with repeating patterns in motion. I was losing myself in this chaos and a new world opened up.”

-Violet Baxter

One of the greatest gifts of my childhood was spending a few times each year in my Great Aunt Violet’s studio. Part of it was spending time with her paintings, and a lot of it was also listening to her music, eating her snacks, watching her dance, and hearing stories from her life in downtown New York City. We looked at her work and I listened to her musings on color, nature, light, memory, and family. After my mother died in January of 2021, I was touched by a deep and ever-present longing for the soft feeling of maternal hands. Visiting Violet, who isn’t related to my mother by blood, I still see gentle glimmers of my mother in the shape of her eyes, the texture of her skin, her loving warmth, and her familiar stories. I had to, in some way, mark the space we share, a holy present bolstered by a lifetime of visits and lineage. The title of this conversation is how Violet has often concluded our visits, so I felt a benevolent sweetness when I heard the words come out at the end of this interview, which took place after a recent overnight stay at her Manhattan apartment.

Gilian Rappaport: How did you become an artist?

Violet Baxter: It’s like asking what it’s like to be me. From my earliest memory, I made pictures. It was how I communicated. I lived through my drawings. In the years that I was not painting, I was a fish out of water.

My fourth grade teacher, Evelyn Licht, was an artist who connected with me and became my lifelong friend. When I was 13, she arranged for my first job on Saturdays designing cake boxes and later helped on my first exhibitions.

I was the oldest of five in a lower middle class family in the Bronx (NY). I attended night classes at Hunter College. Two years later my high school classmate at HS Industrial Art, Eva Hesse, invited me to the Green Camp, the campus of Cooper Union (NJ). She was already a student and invited me to spend a weekend with her there. That’s when I found out that Cooper Union was a scholarship school. A major day in my life was when I got the envelope that said I was accepted. Needing a job, I applied to night school and happily attended there for five years, gaining a certificate with honors in 1960.

Gilian: I wish I could have visited your first studio. Will you tell me about it?

Violet: In the 60s, I had a studio on the roof of a factory building at 47 E.12th Street in Manhattan. It was an unheated, 30 square foot shack with four windows and a skylight. The halls were mostly unlit, and very, very dark. It was a high walk-up so not many people would make it up there. Once, at about two in the morning after working at the studio, I stepped on someone who was sleeping on the steps. In 1962, preparing for a solo show at Brata, a Tenth Street Gallery, I schlepped many large paintings up and down the stairs, a demonstration of my energy. The studio faced a courtyard and looked into Willam de Kooning’s studio. One darkened day I stood on the fire escape and there he was. We stared at each other until the sky brightened.

Gilian: Will you describe the evolution of your work leading up to when you started painting the New York City Greenmarket Farmers Market?

Violet: From Cooper U, my paintings were large and abstract, often referring to childhood memories of walking through the woods at Baxter’s Corners, in Monticello, New York. My father was born there and it was where my family spent summers until I was 14.

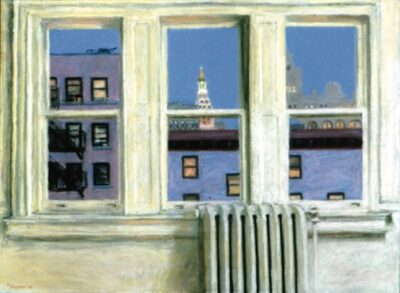

Later, in my studio at Union Square, I turned to realism, mostly using pastel to try to describe what was in front of me, the wall and my window. The challenge, since it was just a wall, was how to make it look vertical on the flat surface without perspectival devices. I wanted to convey the visceral feeling of looking at the wall, and what it felt like. For the next few years, I was obsessed with walls, windows and the view across the street into other windows.

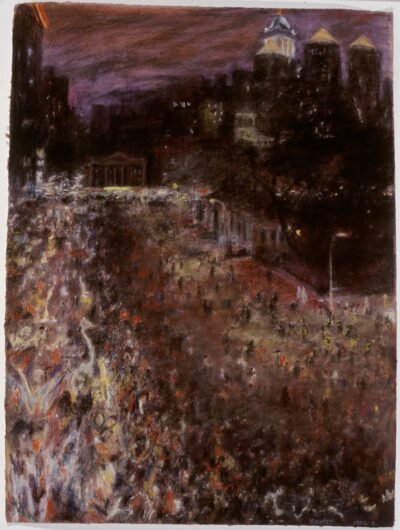

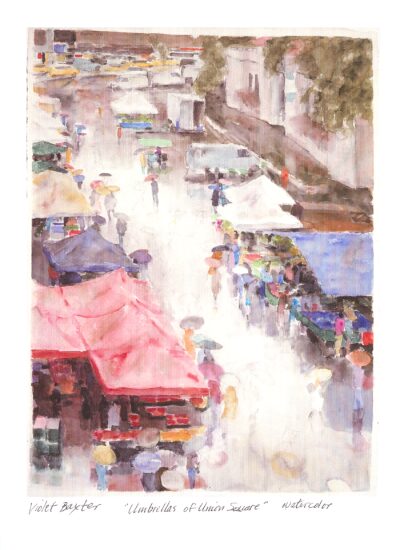

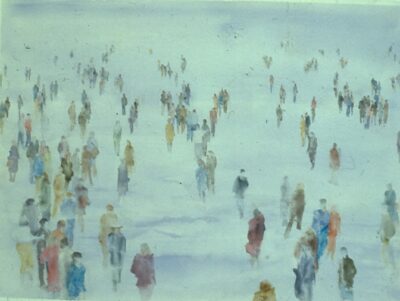

Violet: Eventually I began what I thought was impossible: depicting the Greenmarket and daily events as seen from the other windows facing east. It turned out to be a major part of my work continuing until I moved my studio to Long Island City. The architect, Barry Benepe, the originator of New York City’s farmers markets, saw my work and brought me to The Council on the Environment of New York and their activities. I exhibited my work at a few of their celebrations, where I met some of our past mayors and other dignitaries. Mayor Koch was the most fun. Once they seated me at Abe Beam’s table. He said ‘Who are you?’ very disdainfully, and I said, ‘I’m an artist, that’s my work’. He was disinterested and annoyed. These funny things happened over the years working with the Greenmarket.

Gilian: Your work has changed several times throughout your life. Where do those changes come from?

Violet: Serious demands have limited my work over the years. Always, when returning to my work, I was changed, thus a change in my vision, like when I became a mother, my energies were redirected. For example, while my daughter Mara was growing up, I did complete a series of mother and child paintings that had a lot of angst. Each time away there was a change of focus.

Gilian: How do you see nature in your work?

Violet: Being in nature is where I feel my smallness. It overwhelms me. I’ve mostly lived in the city. In 1996 at the Vermont Studio Center, it took me two weeks to comprehend what I was even looking at. I made paintings that were banal, something was badly missing. After two weeks I gave up trying. I looked closely into the bushes in front of me, locating the patterns of the leaves, and into the racing rivers with repeating patterns in motion. I was losing myself in this chaos and a new world opened up. I made more work in the remaining two weeks there than I did in the preceding year. It was a profound experience, and it changed the direction of my work.

Gilian: How do you feel about social forms of art? Socially conscious art or participatory art?

Collaborative work can be really exciting. You get that mostly in theater. When I was a teenager I did a stage backdrop for my cousin who was an opera singer. I’m currently a member of a gallery in Chelsea, NYC, an artists collective, and the Federation of Modern Painters & Sculptors. But mostly I look for authentic, personal expression. I see interesting outcomes from collaborations. More minds working on the same kind of thing.

In terms of impact, painters, through the centuries have worked with social commentary. I think of how Goya’s “The Disasters Of War” (1810–1820) can really make you cry.

Gilian: What music do you listen to?

Violet: I did calligraphy listening to Gregorian chants. I love classical music. Of course, Bach, Chopin, Baroque music; pop songs from the 60s, The Beatles, Joan Baez, and all those wonderful socially-conscious singers. Contemporary musicians that echo nature with electronics. I like the liturgical, mystical music of Arvo Part, the Estonian composer. And then again, I love African rhythms. As a kid living in the Bronx, there was a radio station that played Chinese music that fascinated me.

Gilian: What artists do you admire?

Violet: Rembrandt, Vermeer, Titian, Goya, Cezanne, Van Gogh, Monet, Bonnard, Paul Klee, Balthus, Mauricio Lasansky; De Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Max Beckmann, Maurice Prendergast, Rezika, Phillip Guston, Wayne Thiebaud, Graham Nickson, Stanley Lewis, Trevor Winkfield, and many more; Hokusai, Utamaro, Benin etc. Too many to list.

Children’s drawings are interesting. I had a book on children’s drawings from around age seven, around the world in different countries. How similar they were in the way they perceived things, that development was really, really interesting.

Gilian: Do you like to dance?

Violet: I love to dance. If I can’t get outside and walk, I dance. Many of my models have been dancers, and my drawings pick up from their movements.

Gilian: Have you taken any memorable movement classes?

Violet: My dance teacher, Elaine Summers, recommended me to her teacher, Carols Speads, who taught breathing with very slow motion. She kept the classes small, since this breathing would actually release toxins. The slowness appeared to allow for clear thinking.

Gilian: What are you interested in now?

Violet: My recent work is spontaneous play, a stream of consciousness, surreal, just letting it happen. It’s all on paper, all small.

Gilian: How are you spending your time these days?

Violet Baxter: My sister is very ill, so my time is divided with assisting her. I’m going now to be with her. I’m starting to learn about gardening. Every other weekend I spend with Richard, whose house is close to Manhasset Bay on Long Island. I planted a tiny pot of daisies there and it quickly became a bush. It is very thrilling.

Violet Baxter was born in New York City in 1934. She attended night schools at Hunter College, Cooper Union, Columbia University, Pratt Institute, and the New York Studio School. She worked as a cartographer and calligrapher, taught calligraphy in a special program for Pratt Institute (1970’s), and subbed as drawing instructor at The National Academy of Design. In 1960, she was part of the 10th Street Gallery scene. She was elected to the board of NY Artists Equity Inc (1991–2015), The Fine Arts Federation of NY (2004–2009) and the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors (1994–present), was an honorary member of The National Arts Club (1999-2012). She received medals from the Audubon Artists Annuals, and the Jane Peterson Memorial Award; The Richard Florsheim Art Fund Grant (2002); and the Albert Nelson Marquis Lifetime Achievement Award (2021). Her work has been reproduced and reviewed in publications including The New Criterion, Art and Antiques, The Pastel Journal, Contemporary American Oil Painting (Jilin Fine Arts Publishing, Changchun, China, 2000); Hyperallergic, etc. Her works are in the collections of The Crisp Museum (SE Missouri State University), Savannah College of Art & Design, Museum of the City of NY, Council of the Environment (NYC), and Consolidated Edison Co NY.

Gili Rappaport was born in New York City in 1988. Gili is a naturalist, educator, curator, and designer working in social and visual forms. Their interdisciplinary practice is place-based and often in natural contexts. They co-authored Field Guide To The Northeast (The Outside Institute, 2017–2021) and co-organized Ralph’s Neon Oasis Beach Party (Jacob Riis Park, 2022). They founded their design and research studio, The Workspace of Gilian Rappaport, in 2016. Their work has been shown at Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, King School Museum of Contemporary Art (KSMoCA), Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Parallax Gallery, and Dream Clinic Project Space, and is in the permanent collection of KSMoCA and Special Collections and University Archives at Portland State University. In 2024, they will publish their book They Call Me The Mayor at Riis Beach, and their book of interviews through KSMoCA. Gili is nonbinary and of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. They live in Portland, Oregon. | art projects: www.gilian.space | design projects: www.gilianrappaport.space | @gilnotjill