Peeling the back the layers

June 7, 2023

Text by Kiara Walls with Jodie Cavalier

“I feel my onion has another audience that has grown inside of it or something.”

-Jodie Cavalier

I lost my grandfather earlier this year and have since been navigating the complex layers of grief. After returning to work following my bereavement leave, I had a conversation with my coworker, Amy Bay, from Northwest Academy, where I serve as the Dean of Students. We discussed my desire to honor my grandfather’s memory by using his belongings to create something meaningful. Amy mentioned the work of Jodie Cavalier, who explores grief by incorporating her grandfather’s items into her pieces. Jodie’s exhibition, titled “Fool’s Gold,” was showcased at Holding Contemporary. I found Jodie’s work inspiring and was intrigued by her approach to grief. I wanted to have a conversation with her to gain a better understanding of her artistic practice and her relationship with grief. This conversation brought me comfort, as it allowed me to explore different ways of processing grief that aligned with my own experience within my family.

Kiara Walls: How are you?

Jodie Cavalier: I am doing okay. I have had a pretty rough year losing a lot of elders, so I feel I’m in the beginning and middle of multiple grieving processes. So it’s been a heavy start to this new year.

Kiara: Yeah. I can imagine. I resonate with that too. I’ve recently lost my grandfather over winter break, which has been my first close experience to grief. How have you been processing your grief? Because, you know, a lot of people refer to grief as a layer of an onion.

Jodie: I feel my onion has another audience that has grown inside of it. I think that when my grandfather died, it was very abrupt, even though he was older. He died from Covid, so the whole weight of the pandemic and all of those fears manifested in something. I think that people who have lost someone during the pandemic have maybe a different relationship to it because of that. I hadn’t really thought of that. Maybe that is part of the onion of grief, collective grief,around the pandemic. I do feel I started to process some of that when I was going through some of his stuff and then I was hit with both of my grandmothers dying in the last year, pretty close together. So it just kind of piled up in a way. I think I’m in the very beginning of it and trying to figure out what processing that is. I think that it’s so different for everyone and I don’t know what it is for me quite yet.

Kiara: I totally feel that. It also resonates with me what you were saying about how different people are experiencing grief at the same time, with Covid. That makes me think of the phrase “six degrees of separation,” but six degrees of grief and how we are connected in that way. I was actually introduced to your work through a coworker of mine over at Northwest Academy, Amy Bay. We were talking to each other about my grandfather’s passing. I was telling her about how I’m interested in collecting his items and somehow doing something with them. Then she told me about your work and your show at Holding Contemporary. I was really interested in your work and wanted to talk to you about your practice. I’m interested in hearing more about what helped you through this experience of grief and what your understanding looks like for you and how you process it.

Jodie: It was a natural kind of progression to make work about my grandfather in general. I actually made work about him before, when I was younger.

Kiara: What was that work of?

Jodie: That work was a lot about the body and when the body begins to fail. He had some health concerns and he had parts of his leg amputated because he had diabetes. I was really thinking about aging and the body and this kind of promise we think the body makes to us, and then breaks. We’re in this together and then our body starts to fall apart and you just feel betrayed by your own body. I think a lot of my work is really kind of based and seeped in the human condition. A big part of that for me and my lived experience is the relationships I make with other humans and even more specifically the relationships I have with my family. That has come through in the work for a long time in different ways. Some work is more overt than others. It came about pretty naturally to start to make work about or around him, ideas of grief, familial things, all of that kind of just came together. I was in conversation with Holding Gallery for years before we did the show, “Fool’s Gold,” together. I just didn’t feel what I was working on made sense in a gallery at that time. When they first approached me, I was doing a lot of community organizing projects and food projects. I don’t have a need for showing that for authoring the community work I was doing; the priority was different. When I started to make work that was more physical, fine art type objects, we revisited the conversation around having a show. I didn’t really think about it as processing of my grief. Now I think about everything as processing grief, in some way. But at that time I was just kind of going through the motions of remembering him in specific stories and his personality, and then going back to my grandparents’ house and taking random objects and remembering things from them. Then it kind of started to accumulate and just thinking about some of the things he believed in and hoped for, and all of those started to surface in a way where I was, I started having more fun with it. He would get a kick out of some of the things that I was making and messing around with, and whatnot. He was always a supporter of weird creative endeavors. He didn’t understand them, but was just supportive of them. I wish I could have shared with him some of the things I made. I think he would’ve got a kick out of it.

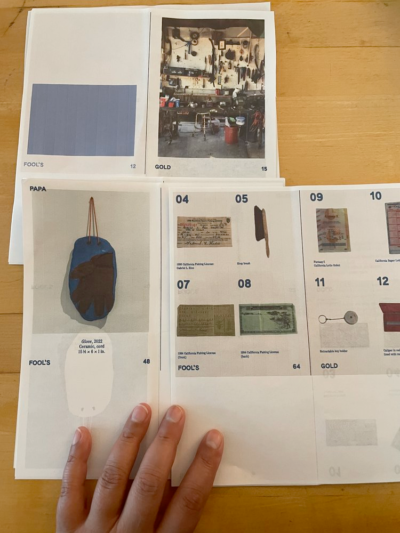

I made a lot of work and then kind of put it into a book form because I wanted to have them hold a different space. There’s a lot of writing that I had been doing for several years about my family, specifically my grandparents, but I wanted to have a place for those to exist alongside the objects. It was really fun. I got to work with Holding Contemporary and, and one of their designers, who is amazing. She basically just donates her time and service to working with Holding. She has a design job with a couple of other folks called Omnivore. Her name’s Karen Sue, we went back and forth with all of these kinds of ideas on how to put the book together so it didn’t just feel like another publication. We put a lot of thought and process behind everything.

Kiara: Yeah. This was beautiful (looking at the publication).

Jodie: Thank you.

Kiara: Was this at your exhibition opening?

Jodie: It was at the end. So we didn’t have a formal opening and instead we had a closing and book release towards the end of the exhibition. I was working on it alongside all the work, but in order to get the exhibition documentation photos, we waited until the exhibition was fully up and finished the design afterwards. My friend, Joanne Handwerg, wrote a really thoughtful introduction piece about absence and longing.

Kiara: I can see some of those details designed in the book. I’m wondering, on some of the pages we see the object and then on the page right next to it, there’s nothing there. Is that speaking to some of the themes around absence?

Jodie: Those two pages where there’s the image of the artwork and then next to it there’s a high contrast absence of the image. We talked a lot about ghosts and ghost images. Then also just the impression, something leaves too. There were a lot of really great conversations I was able to have where there were some aesthetic technical decisions, but they were all made from a conceptual and poetic place. It was fun to talk through what it means to have a certain kind of decision that impacts the reader and even things like paper choice and what that feels like. There’s also a clear film that also mimics that ghost quality.

Kiara: This is beautiful. It sounds like your process or approach with this body of work was an aesthetic approach, but also a theoretical approach, like bringing the ghost aspect into the work. I think the way that you present it is really amazing because from being the reader, I could sense some of what you were saying just now within this. Have you thought about where the work could live in the future? Once you’ve done this show, have you thought about presenting the work in other places? Or how do you feel about it being presented in other places?

Jodie: I’m definitely open to that.

Jodie: Yeah, they have lives, I think, where they exist in this one wave and then in book form. I was also pondering how objects could possess autonomy and be strong enough to exist outside of the exhibition. I’m not opposed to any of that. I have a practice, especially with object making, where I often Frankenstein old pieces together. I was brought up to be resourceful, so sometimes I take a piece apart and turn it into something else. I haven’t done that with any of these works, and I don’t know if I will, but I try not to be overly precious about some of the things. I think they have their own why, so why not.

Kiara: You said you don’t want to be overly…

Jodie: Precious, yeah.

Kiara: And you don’t.

Jodie:If I needed to use the base of this sculpture for something else and didn’t have the resources to make a new one, I would just have to make the decision to use it, you know? I also think that, for a lot of reasons, I haven’t had the luxury of having a place to store all these things. Maybe a storage unit or something, but I don’t want to end up with a huge collection of objects I’ve made just sitting there. It would be much better for people who enjoy and find meaning in them to have them. And many people do. That’s also why my work often fluctuates between objects and non-object forms, or even prints and works on paper that are easier to distribute or more accessible in that way. I guess I’ll have to think more about it, but right now, I can’t think of anything I would never give away, you know?

Kiara: Yeah, I get that. I believe social practice art could be an avenue where you don’t have to worry about those types of questions because there’s an ephemeral aspect to the practice. Can you talk a bit about how your work incorporates social practice art or share some projects you’ve done in the past that have incorporated social practice?

Jodie: Yeah, I never really thought of myself as a social practice artist, but I’ve had many conversations with other artists and curators where it becomes part of the conversation. I think of it as an intersection between my creative practice and social practice on a spectrum. Artists are probably somewhere on that spectrum of social practice. For me, I’ve been interested in the mundane, the domestic, and the human experience, especially as it relates to my family, storytelling, and narrative strategies. That blurs the lines between my creative practice and my home life, where a lot of what you might call social practice originally occurred, where those lines are blurred. In addition to that, my interest in teaching, cooking, and sharing experiences with others has built up in a way, as well as the community work I’ve done. So now there are different areas where you can say the community work I do is social practice, or the projects where I mail postcards, letters, and other print material, they have a history in that kind of practice. The way I bring those two ways of looking at the world back into the studio ends up being a blurry place where those two things exist. It’s not always clear, but sometimes it fluctuates. Over time, it changes. When I was a young student making a lot of work, I didn’t think about it in relation to the social practice art movement. I saw it as a separate thing, with some intersections with performance and music. Now we have a different language and a lineage of artists coming out of social practice, especially in this city. It’s a bit clearer now. I wonder how I or others might conceptualize or contextualize the work, not just the work I’m making, but the work others are making, in 10 years time. It could become part of that canon or have an offshoot or something like that.

Kiara: Yeah, that’s a really good question, and it’s something to think about. Before I found this program, I wasn’t really aware of social practice either. I believe many people have the capabilities of being a social practice artist based on what they do in their everyday lives. However, they may not formalize their practices in that way simply because not everyone knows about social practice. But I do sense that attention around it is growing, and I’m excited about that too. When I think about social practice, it makes me think about inclusiveness. It feels like a part of the art world or art scene that is more accessible.

Jodie: Yeah. I think that’s another intersection that I’ve thought about for a really long time, which is that I’ve always wanted my work to be accessible to non-artists. I think a big part of that was because I wanted my family to be able to experience my work and not being an artist shouldn’t be a barrier to experiencing it, and understanding it. That doesn’t mean that the work itself can’t be layered and have more theoretical or intellectual themes and experiences and takeaways from it. I think that for me, it’s so important when I’m working with an idea to try to translate it in some way, through objects or whatever installation, that is accessible.

Kiara: Yeah. That makes me think about how earlier in the conversation you were talking about how you were speaking with Holding Contemporary, and you were thinking about the work that you were making at the time, you didn’t necessarily want to formalize your community work in a gallery space. Is that also talking about how you’re translating these things? How do you feel about your role as an artist and when you’re doing social practice projects or events with your community, and how do you formalize those things? What are some thoughts you have around authorship?

Jodie: Yeah. That’s a great question. When I’m doing community work or collaborative work, I’m not interested in authorship. I suppose in a way, it’s important for my collaborators on those projects to share that value. It doesn’t mean that it can’t be aesthetic or considered in those ways but there’s definitely something else to prioritize in those contexts. I worked with Amanda Lee Evans, for example, who had a big project called The Living School. She brought me into work with one of the youths that lived on the site. It wasn’t a formal mentorship, but it was based on the social practice program’s mentorship program. I ended up coming over to work with one of the youth there, Zira, weekly for months. For me, the relationship that we built together around being curious about art, cooking, talking and learning about her and what kids are into,that became the priority, and everything else kind of fell away. I didn’t need to document the work we made or the fact that we were doing this. I remember thinking that I could go through those processes, and that this relationship was also a project, but I didn’t think we needed any more pictures of an artist hanging out with kids. I’m also not one to take a lot of photos,. I think that’s a very specific kind of thing. But for me it’s so much more about experiences than it is about an image or a specific aesthetic or something that might be clearly “Jodi’s work.” When you look at all my projects together, you’re like, oh yeah, there’s an aesthetic at play here.

Kiara: There’s an aesthetic at play?

Jodie: Yeah. There’s an aesthetic maybe at play, but it’s not stylized.

Kiara: I feel the aesthetic could be the experience.

Jodie: Yeah. There’s consistency. Going back to the full school exhibition, people talked so much about how they felt in the space more than they talked about the objects. That didn’t to me mean that the objects weren’t powerful. It was all working together, but it really is so important for me to think about , what people experience and what they walk away with. And so there were so many decisions made in that show to really guide viewers through that. And so, even when you see a wall of a bunch of old stuff, at a certain point you’re not even thinking anymore about it being an art show or a collection of works or what is real and what is old. You start to recognize the feeling of experiencing somebody’s collection of things where the handmade stuff and the real old stuff blend in together at a certain point. And it doesn’t matter anymore because you transcend into experiencing the entire installation as one big thing.

Kiara: I really appreciate that description cuzI’m a visual thinker, so when you’re describing these things, I’m thinking about experiencing the pieces and going through that. I wouldn’t call it a separation, but, out-of-body experience comes to mind because it seems like you’re zooming out, and that it’s bringing in more thoughts and feelings that are not necessarily related to the object or art itself. But those feelings are coming out of that experience looking at this piece of work.

Jodie: Totally.

Kiara: Yeah.

Jodie: Off course I have an experience that I’m attaching to the objects and all of that. But again, there are so many visual cues that lead a viewer to, not necessarily interpretation, but just narrative, because I also think it’s, it is all about storytelling. I think that especially in this show, the objects are all about storytelling. There are lotto scratchers and tools that have been used, and other really handled objects, ceramics and clay that you have to handle and manipulate, so they have their own history. Everything is loaded with meaning and story. And so I’m guiding viewers into that. I’m welcoming them into that and guiding them through it.

Jodie: But I think the more meaningful things that can come out of it is how someone can be reminded of their own personal experience, and maybe their own experience with their elders. And I had a lot of people who were like, Oh my gosh, some of these objects reminded me of my father, my grandfather. Because they are not that special: there’s an old pair of pliers. And to me, those pliers are special because my grandfather held them and used them, but they’re also just anybody’s grandfather’s pliers.

Kiara: Yeah. It reminds them or it resembles something from their elders. Yeah. And I think you’re talking about storytelling, how the object has a story story in itself, but you’re also inviting the viewer to go through their own story by asking what memories are sparked from me looking at this object. And they’re going through that process of remembering. It’s that sentimental value. Although it is a common object, it’s able to spark sentimental value for viewers that are interacting with the work.

Jodie: Totally.

Kiara: Yeah. Definitely. This is my last question. Are you working on anything currently that you can share?

Jodie: Oh I’m always working on a bunch of stuff. It’s not all finished, but I had a show in Santa Rosa. I got that work back pretty recently, and so I’ve been unpacking that and figuring things out. I am also going togo back to that similar area in Northern California for a residency later this year. And I’m working on another publication. And I’ve been kind of working on this project in the background for a while now, I guess years now because, you know, the pandemic has warped us into years now.

Kiara: Yes. Definitely.

Jodie: But it is a book that has recipes and prompts and invitations.

Kiara: Hmm. Is it tapping into your interest in Flexis?

Jodie: In some ways, yeah. But it’s also related to the fragment of remembering

Things. Like how a lot of the domestic kinds of tasks that my grandmothers did and what I remember and don’t remember from that time. So it’s in the middle state. It’s not in the beginning cuz I’ve been working on it for a while. But I’m gonna be able to spend some time out at this pretty cool residency and they actually have a really nice cooking setup. So I think what I wanna do is focus my time more on some of the actual food projects that might be included in it. Cuz I have a lot of the other more poetic gestures that might be included. And I need to buckle down and get some of these more practical, straightforward recipes down on paper.

Kiara: That sounds really exciting. I just love and appreciate the fact that you’re creating work for your grandfather and now you’re creating work for your grandmother’s grandmothers, and I think that’s really beautiful. I’m excited to see the publication.

Jodie: Yeah. Thanks. We’ll see what it becomes. I’m excited to spend some uninterrupted time and really turn it into something.

Kiara: Definitely. Yeah. Well, let me know.

Jodie: Will do.

Kiara: Thank you so much for your time.

Jodie: Thank you.

KIARA WALLS (she/her) is a social practice artist, educator, and dean residing in Portland, Oregon. She holds a Bachelors of Art in Graphic Design from California State University of Northridge and a Masters of Fine Arts in Art and Social Practice from Portland State University. Walls’ work explores the layers of Black sovereignty through creating conversations, film, and site-specific installations. Her practice often involves community engagement and collaboration, inviting participants to join in the creation of the work. Walls seeks to engage in dialogue and reflection on themes related to trauma, identity, healing and intimacy. In her project, “The Black Box Experience Series”, Walls’ invites audiences to join the conversation around “What would reparations look like today?” through stepping into an experience other than their own. Walls has completed residencies at Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles, California, and Sunset Art Studios in Dallas,Texas. She was awarded the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art Precipice Grant for her collaborative project “Kitchen”, which explores the relationship between hair and intimacy while centering the experiences of Black clientele and natural hair practitioners. Walls seeks to challenge and disrupt systems of power and oppression while empowering and elevating the voices of marginalized communities.

Jodie Cavalier (she/her) is an artist, educator, and artist administrator living in Portland, Oregon. She earned a BA from the University of California, Berkeley and an MFA from Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland, Oregon. Her work has been exhibited with Converge 45’s Portland’s Monuments & Memorials Project in Portland, OR; the Schneider Museum in Ashland, OR; the deYoung Museum in San Francisco, CA; the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, CA; CoCA in Seattle, WA; Practice in New York, NY; and Städelschule in Frankfurt, Germany; among others. She has participated in residencies such as ONCA in Brighton, England; the Center for Land Use Interpretation in Wendover, UT; Wassaic in Wassaic, NY; and AZ West in Joshua Tree, CA.