People Are Art

June 2, 2022

Text by Laura Glazer with Melodie Adams

“I’ve never considered myself an artist, even though I’m telling kids that everyone’s an artist and I really believe that. Why am I separating myself from that? I’m an artist, too. I need to start saying that to myself: I’m an artist.”

MELODIE ADAMS

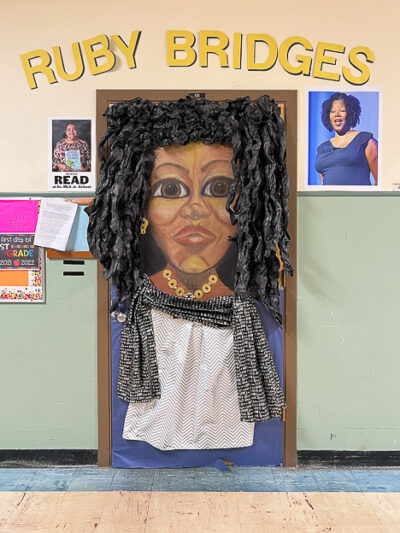

Ms. Melodie Adams is a first grade teacher at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School in Portland, Oregon, where she has worked for 14 years. She drew a portrait of civil rights activist Ruby Bridges and displayed it on the door to her classroom in celebration of Black History Month in February 2022. I saw the artwork at the beginning of the month and was awestruck by the drawing. I was so inspired by the texture and dimensionality of the hair that I photographed the work and returned for a second look at it the following week. I remember thinking: the person who made this is very inspired and really knows what they’re doing. I noticed that other doors in the school were decorated, too, and then I photographed each one.

I learn in the King School community, too, as a graduate student in the Art and Social Practice MFA Program at Portland State University. Each week I attend class at the school because the MFA Program co-directors founded a contemporary art museum embedded within the school called the Dr. MLK Jr. School Museum of Contemporary Art (KSMoCA).

One day after class, I was introduced to Ms. Adams. I was very excited to find out that she was the artist behind the drawing of Ruby Bridges and I felt like a fangirl meeting my idol for the first time. A few weeks later we talked about her drawing practice, the Black History Month Doors, and what parts of her personal and professional life led to the project.

As I listened to Ms. Adams, I kept thinking: I want everyone to hear what she says. Like how her curiosity led her to travel outside the United States to explore her genealogical roots in Nigeria. Or that she chose Ruby Bridges because she wants her students to know that even as young people they have the power to change their worlds. And that despite no one in her early life encouraging her to go beyond what felt possible, she found so many ways to do just that.

Around this time, I learned about poet, activist, and educator June Jordan’s 1970 speech to school librarians, in which she encouraged them to bring young children into libraries by asking them to write their own books about what they want everybody to know or what they think is important but that nobody seems to care about. I used Jordan’s advice as the framework for sharing Ms. Adams’ stories and work with a broader audience in I Want Everyone to Know: The Black History Month Doors at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School, a book I published in May 2022 with KSMoCA. It includes the following interview and photos of the artwork on all of the classroom doors created for Black History Month by over 300 artists who are students, teachers, staff, parents, and supporters of the school—a collection of what this community of learners and educators want everyone to know.

Laura Glazer: What led you to teaching?

Melodie Adams: I always think about how my life might have been different if I had different opportunities or if I had people in my life who cultivated things, brought those things out in me, and helped build my confidence. And that’s one of the reasons why I chose to be a teacher, because I was going to be a lawyer. I was very much an arguer, a person who wanted to defend my opinions and defend my case about things. Also, I’ve just always kind of been a person that believes in fairness and social justice. Plus I’d never thought I could ever be anything, to be completely honest with you. I didn’t grow up with the mentality that you can do whatever you want to do. I think when you live in poverty and you have a single mom who’s just trying to make it—even though my mom’s white—she came from a poor or working class, white family.

My grandparents were from Oklahoma and they came out here [Portland, OR] during the Dust Bowl type of thing. I don’t think she was encouraged or taught that she could do anything and be anything. She came from the era of a woman’s job or a woman’s position is to be a wife and make her husband happy. That’s how she was raised. So going from your parents’ home to your husband’s home, that was the trend in her day, that’s what you did. You became a housewife and a mom. So, the fact that my mom went outside of her race and had children, wasn’t married, she just broke all the rules and I’m sure it cost her dearly.

Laura: Do you think that you bring this into your classroom?

Melodie: My philosophy, or…?

Laura: Yeah, some of the things that you were just saying… I was imagining that you impart that to your students.

Melodie: Well, I’m a very transparent teacher, educator. Of course, I do not want to put my belief system on others. So there are certain topics that I will not teach kids, I will say to them, “Oh, that’s a subject that you want to discuss with your parents.” It’s not my place to talk about that. And then of course it depends on the age. But our society is really kind of forcing us to educate kids about lots of things, because they’re exposed to it everywhere. It’s all around them all the time. And so I feel like I have a responsibility, but I also want to respect their parents. When I first became a teacher, I was trying to figure out, what’s my style, what’s my thing? What’s gonna get kids interested in what I have to say? Especially being a struggling student myself.

Laura: Really?

Melodie: Yeah. I was not interested in school. I wasn’t interested in reading, any of that kind of thing.

Both of my kids have been in the arts. I exposed them to that at a young age; all kinds of things: graphic art, dance, music. They chose to be dancers. They were both Jefferson Dancers. My daughter is still really into dance and she’s very talented musically, so she’s been writing music and trying to get ready to put an album out.

My son wanted to do more creative things. Besides just, he’s just good at computers, he’s kind of a natural at that kind of stuff. He was working at a production company and he got laid off like everyone else and was like, “I’m going to start my own business.” And I’m like, “In the middle of a global pandemic?” Because I didn’t get that you can do whatever you want, I always encourage my kids to shoot for the stars and do whatever. So, the fact that he did that in the middle of a global pandemic, I was like, oh, that’s so gutsy, because I really lack a lot of confidence in myself. I’m very good at boosting the confidence of others and driving that home and getting others to be excited and pushing them to try this, and “You’re going to be great at it.” But I have a really hard time doing that for myself. That’s one of the reasons why I’m like, what am I waiting for? I’ll be 51 in a couple of weeks and I’m like, well, it’s not over just because I’m in my fifties now. I want to kind of see what I can do. That’s why I went to Nigeria all by myself.

Laura: You went by yourself?!

Melodie: Yep. Last summer, I’m going again this summer. I just was like, you know what, why not? So I did. And that was the first time I’ve ever left the country in my life.

Laura: Is there anyone in your life who boosts your confidence?

Melodie: Yeah. I have a really, really good friend. I’ve known him since I was in my early twenties. We actually met when I went to audition to be a backup singer for an Elvis impersonator band and he was the baritone singer for that band. And that’s how we met and we’ve been friends ever since. In fact, we live together now, we’re roommates.

Laura: Really?

Melodie: Yeah. He’s in his seventies. He’s 20 years older than me. I met him when he was in his early forties, I was in my early twenties, and we’ve been doing music and hanging out ever since.

He’s been like a best friend, kind of like a father figure, and many other things in my life over the years, and helped me financially when I was raising my children by myself, and now he’s aging and he’s not working. So, the roles are kind of reversed a little bit. I’m kind of supporting him a little bit more and just helping him in the ways that he was helping me.

Laura: That’s powerful.

Melodie: He’s lived a pretty privileged life; he’s a white male in his seventies, born on the east coast, he lived in Connecticut. I’ve actually really helped him understand his white privilege, things that he’s never really had to think about. I’m really kind of an in-your-face person when it comes to that kind of stuff, I’m very transparent. That’s kind of the beautiful thing about our relationship, is he doesn’t take it as I’m being aggressive, ’cause he knows me. But he’s not a stranger to point out to me, hey, you might want to come at it this way.

He has definitely been one of my biggest cheerleaders. He was telling me the other day, “I’ve known you all this time and I still feel like I’m learning so much more about you. You’re so amazing with your cooking talents and you raised great children and now I’m looking at this amazing art that you’re doing. I’m blown away that you’re evolving into this magnificent person in front of me. And I didn’t know what you already had and it’s just more and more and more.” He’s been very, very supportive to me. I often think about it ’cause he’s older than me and what am I going to do when it’s his time? It gets me emotional because I can’t see my life without him in it.

Laura: What is his name?

Melodie: His name’s Richard. When he was working a lot, he made pretty good money and he was always taking me to places to help me experience things that I never experienced before because I never had the money. My mom didn’t have the money.

He took me on my first plane ride. I didn’t take my first plane ride until I was like 27. He took me to the east coast and we toured around for several weeks. I went to New Hampshire, Connecticut, New York, Boston, and all these places. He delighted in the fact that he was able to show me these things. He’s like, “I wish I had so much money because I would be taking you all over the world, you deserve to see these places.” That’s his wish for me, that I’m able to travel and experience all these things.

He would also take me out to expensive dinners when I was going through culinary school so he could expose me to white tablecloth dining and real gourmet cuisines and things like that. We traveled to New Orleans together and we went to really great restaurants there. He’s always helped me have those kinds of opportunities.

Laura: You mentioned that a couple of days ago he said he’s still learning about you. Was there some conversation that prompted this kind of deep exchange?

Melodie: We talk about so many things and I think the topic came up about me finishing a drawing that I started probably about a year and a half ago. I’ve been so busy, that during COVID I spent a lot of time getting to know myself in that art world vein. I started off with just trying my hand at drawing. I was drawing people, drawing faces and I’d just draw whatever image was coming to my mind. Then I started thinking, gosh, how do people catch the likeness of actual people?

I see all these magnificent artists and I don’t want to do that; I want to be able to draw someone that someone could recognize. So, I watched a few tutorials on YouTube. I started sketching eyes and sketching lips, and just watching about how to shade and lighting and just that kind of stuff.

A friend of mine sent me a picture of himself. He had just got off work and he was just laying there. I’m like, that’s a really cool picture. He’s Oaxacan and I’m very intrigued by ethnic people and I just think that they’re art; like people are art, you know what I mean? Like the structure of their faces and stuff. So, I just started trying to draw him from that picture and I took pictures, too, of all the different stages. I just worked and worked. I could get lost and do work on this for hours. I would be like, oh my gosh, I’ve been doing this for three hours. It just started coming alive, you know?

Laura: Was that one of the first portraits you did applying your new skills?

Melodie: This was the first thing I drew where I actually was like, I think that really looks like this guy. I was pretty pleased. I’m still not even done with this portrait. [Shows a picture of the drawing saved on her phone.]

Laura: Wow! It is a cool picture.

Melodie: I don’t even know art language, you know what I mean? This is totally a new thing for me. Then I was like, well, I want to paint. So, I started thinking, what do I want to paint? I want to paint women. I want to paint cultural women, in their cultural garb.

I was watching this video of the Día de Muertos and I snapshotted it. I was like, I’m going to draw this and I’m going to paint this because I want to try my hand in painting. I started painting it and this is the beginning of me painting it. This is as far as I’ve gotten so far. [Shows photo of the painting in process] I’ve been so busy back at work, I haven’t had time; I’m gonna finish this at some point. It’s in acrylics and then I’m gonna insert people throwing flowers in the air, and then along this area because I want it to be really bright.

Laura: Wait, what happened in your head when you were like, I’m going to add this? Because you have the snapshot of the video still, but then you were talking about adding magnolia. Where did that idea come from?

Melodie: I guess because I wanted it to be culturally appropriate. And so you could really kind of have a conversation about what’s going on in the portrait. I wanted it to have movement. That’s another reason why I liked capturing that because I feel like I wanted it to come alive and be really bright and colorful. Also, just making it my own, using that snapshot as an inspiration really and then making it my own.

My dream is to have a space where I have a room where I can just create art, I can just do art. I do stuff here with my students.

Laura: In a sense, for as long as you’ve been a teacher, you’ve been building up to this moment of seeing yourself as an artist.

Melodie: I guess so. I often draw things with kids and I’ve always kind of integrated art. But I’ve never considered myself an artist, even though I’m telling kids that everyone’s an artist and I really believe that. But why am I separating myself from that? I had to start thinking about that for myself. Why am I separating myself from that? I’m an artist, too. I need to start saying that to myself: I’m an artist.

When I decided to do the [classroom] door, I just decided to do a door: my door. I teach the kids about Ruby Bridges for a couple of different reasons. She was a first grader when she made history. My kids are in first grade. She was from a time where kids themselves weren’t listened to, no matter what color they were; kids were kids and they had a place. She made history, she changed things. Many people don’t even know who she is. I think that’s really sad because she made a huge impact. That’s another thing I get tired of: so many people of color, especially Black people, do not get recognized for what they have contributed to the advancement of this country.

It’s all these typical, white males who mostly get the credit for everything. I also look around and I see successful people. Like I used to live over on 20th Avenue, so I go through the Alameda neighborhood a lot when I go to Lloyd Center or other areas. I’m just looking around, like, how did you get this beautiful house? Did you get it because you worked really, really, really hard and saved? Or did you get it because of generational wealth, because of an inheritance, because you are privy to being a CEO of a company, or you got a start somewhere, and were able to build this? How many people in this country who have all this money really have worked their fingers to the bone from the ground up without any subsidy, without any help, without any little piece to get started? That bothers me when I see so many people work so hard and they die. My own mother, who is a white woman, is in a care facility. She’s doing fine, but where was her generational wealth? Don’t have it. I’m not going to get an inheritance or anything else when she passes. I’m trying to do that so my children will get some generational wealth.

Going back to Ruby Bridges, I’m very passionate about race and educating people about race, inclusion, and the contributions of people of color and spreading that word and getting people to understand that our single story is not slavery; we come from so much more than that. That’s one of the reasons why I went to Nigeria because I wanted to see—I’m almost 17% Nigerian—where do I come from? A lot of it has been self-discovery of myself and who I am, because what a lot of Black people suffer from in this country is we’re like people with no country. Because we get the same narrative for how we came about. There’s a lot to be honored and a lot to celebrate about that. But there’s also so much more to our lineage. Like even white people came over here knowing they have a Scottish crest or they have the… you know what I mean? We don’t have that and it makes me sad internally. They came here with their traditions and language, and we brought what we could. It really is wounding for me.

So, teaching my kids about Ruby Bridges, teaching kids at a young age about how they can be powerful, how they can change history, is important to me. Like, “Look at her, she was your age! And she made a huge impact.” It’s sad that she’s not talked about enough, not around here anyway. I could be overstepping as far as on the east coast or down south or something like that. But obviously we’re not getting as much education around people of color here in this town –on the west coast –the way people get it over there. I know that from being in Louisiana and being in Arkansas and being in those places, there’s a different sense of pride around culture there for Black people than it is here. This is my personal experience.

The first time I ever went to Louisiana, to New Orleans, I went for a race summit. I met people from all over the country and some people in different parts of the world who came together to talk about the impact of race in education and the lack of opportunities.

One of our keynote speakers was Ruby Bridges. She told the story from her mouth, of the experience of what it was like being a child going to school every day and being spat at and called “nigger” and told, “You’re not welcome here.” And she walked through those people every day as a little kid in her little dresses and holding her book bag and going in with marshals walking beside her. She talked about her experience with her teacher who was sent from Boston to teach her.

To the public’s eye, she was going to school with white kids. That was the whole point, right? To end segregation and for her to be able to be in a classroom with white kids, but that wasn’t happening. She was in a classroom all by herself with one teacher. She could hear the other children next door laughing and playing and I remember her saying that she was so curious about why she didn’t get to do that. So her teacher, who was a white woman from Boston, told on them and said she was still not in the same class as the other kids.

Those old school buildings have little doors that you could use to go from room to room. I saw similar doors at the Metropolitan Learning Center in Northwest Portland and that’s what I imagined she had in her classroom. One day she opened up the door and went through and the teacher helped her do that. She said the little white kids said, “We’re not allowed to play with you, we’re not allowed to talk to you. Our parents said we can’t play with you because you’re a nigger.” She said, “Well, I can understand that, I have to listen to my parents, too.” She just understood that they’re doing what their parents told them, they’re being obedient, not even really understanding the big picture.

Her story that she presented to us gave me a whole different perspective, because we heard it from her. I just have a lot of respect and admiration for her. Then the fact that she is still going around talking about this experience today. That’s why I chose Ruby Bridges as she is today on my door, and not the typical famous picture of her being the little girl. I taught my students about that and showed them who she was as a kid. Then I also showed them that she is still here and I told them that story—not in as much detail—about me seeing her.

I drew this image of her as a woman now. I started working on it little by little after school, trying to figure out, okay, I can put this picture and this construction paper together and make one big piece of paper on my easel. Then little by little, I just started creating her likeness.

Then I emailed the principal and I said, “I’m going to do a door for Black History Month. I thought it might be cool if everyone participated in it, so we’re teaching kids about Black history and it’s not an afterthought, and everyone can do a door.” I was really pleased and surprised that we had 100% participation, everybody did it. I was so proud of them.

At some point, I went around with my students because I hadn’t even seen all the doors. Even the principal did a door, the office door. I was like, “Wow! I’m so impressed.” We looked at all the doors and it just seemed like everyone was really excited about doing it. Moe [fourth grade, student] and their mom were working on a door upstairs and they were just so excited about doing it. And the office gals and their door, everyone was just really into it. It was really cool.

Laura: Where did you make the drawing of Ruby? Was it in your classroom or were you working on it at home?

Melodie: I was making it here at school. I worked on it a little bit on my lunch hour and after school. I would be sitting here with my classroom door open and I have my big easel and people walk by and go, Oh, what are you doing? I had Ruby’s image right here and I was just working on it little by little with oil pastels. Just using my hands, trying to shade, trying to think of what colors and things I could do to highlight. I probably would’ve spent way more time on that, like really trying to get the likeness. But I think it’s pretty good considering I only worked on it for a few weeks.

Laura: Where did you get the idea for the hair?

Melodie: I just figured that long rolls of paper that we have can be manipulated. I looked at the texture of her hair in the image and figured, I can bunch it up, I could twist it, I could do different things to make it read as that texture. I showed Ms. Pookie how I wanted it and she helped add a lot of that hair.

Laura: Wow! So, you had this idea in January for your own door?

Melodie: I’d been thinking about doing a door for a couple of years, but time gets away from us and I just would never have time.

Laura: Plus, we weren’t in school for over a year, too, so you didn’t even have a door!

Melodie: Right, right. But I also knew that if I did decide to do this, it was going to be a bunch of extra time, my free time. I’ve had a lot of crisis in my life and a lot of different things have happened and I have been at my capacity for a long time. But when I started doing art over COVID, it made me happy. I feel like amongst the uncertainty of what this global pandemic was going to do—didn’t know if I was going to get it or my loved ones were going to get it—it was at a time where there wasn’t a vaccine—it was just like, well, these are the cards that we’re dealt, so I have to try to be positive. I can’t just be scared and worried and wondering what’s going to happen, so I started getting into art.

Laura: Do you recall being a child thinking about art or drawing?

Melodie: I feel like I’ve always liked to draw and do art. I really started getting into it more in fourth grade. I had a really cool art teacher and we did all kinds of cool stuff: sand art, art with legumes, and things like that. I did a couple of cool things that I felt like made my mom proud of me. I didn’t really think much of it because, once again, there was no one promoting and encouraging me along this vein. It was all about surviving and dealing and there was substance abuse in my family, just all kinds of things. That’s why I think about how, had I been in a family that was a little more stable and not as dysfunctional because of poverty and domestic violence, what would I be doing? How could my life be different? Both of my brothers are musicians and they were 10 and 12 years older than me. I feel like all the extra money went to their instruments and went to their stuff and there wasn’t really much extra. I also sang and was interested in that, but no one really cultivated that in me, so I never really pursued it and then had kids young.

Laura: You went to Nigeria during COVID and I was thinking about the trip and how you have this blossoming, this coming up of “I’m going to try drawing. Where am I going with this drawing? What do I need to know?” Then you do the portrait of Ruby Bridges as an adult on your door. I keep sensing this timeline, this trajectory. Do you write at all?

Melodie: Not really, but, I mean, I didn’t do art either, so, I don’t know! My daughter writes the most beautiful songs and she writes this music and I’m just blown away about it. Like, “Oh my gosh, you’re so talented, I wish I could write a song.” She’s like, “Mom, you can write a song.” I’m like, “No, not like that!” I want to write a children’s book, but I don’t even know how to begin, I don’t know how to start. So I can’t say that I don’t; I don’t know.

Laura: I like that, “I can’t say that I don’t.”

Melodie: I never thought I was going to go to Nigeria in a million years. I was like, how am I going to do that? Just like I never knew I was going to be able to go to culinary school. I was flabbergasted when they said, “Well come in for an interview.” I said, “What? I can come in for an interview? You mean, I might be able to go here? There’s money for a loan for me to go here?” And the woman was like, I have never met anyone so excited about attending this school. ’Cause I was like, I get to go here, I get to learn culinary arts from all these different chefs. I was so excited.

That experience changed my life because I was a single mom. I actually was at home with my kids watching TV and the commercial for Western Culinary Institute came on and I was like, could I do that? Because I already loved to cook, you know, and my family was like, you’re such a good cook, Melodie. My kids were little and I didn’t want to wait until they’re school age; I didn’t want to be on welfare until then, you know?

I decided to call Welfare. I told them, “I don’t need you to send me money anymore, I just need you to help me with childcare because I want to go to school.” They said, “Well, you have to go for 30 days before we’ll okay funds for you.” And I’m like, “Who’s going to watch my kids for free for 30 days? I don’t have the money.” Well, my brother was a musician. He was like, “I’ll do it ’cause I have gigs at night.” He ended up doing it and later, they paid him to do it. He watched my kids during the day and I went to culinary school and he got paid for it and I didn’t have to have a stranger watch my babies and it changed my life. It really, really changed my life.

Laura: From a commercial?

Melodie: From a commercial. Yup. I was just like, I’m doing it, and I did it! There were 65 people in my cohort, five women; two of us graduated, two women in a very male dominated field. I was called a “bitch” and all kinds of crazy stuff. I was amongst all men from all over the country, 85% of people at that time came from other states. I met people from everywhere and I was not putting up with that kind of stuff; you called the wrong woman a bitch, I’ll tell you that right now. I had to fight for myself all the time and I’d get tired of fighting.

I was just thinking about that the other day, like I had to fight for everything. That’s another reason why I’m like, I want to do something grand. Why can’t I earn a really good living? I want to retire early and travel and talk to people. Give speeches, talk about race, talk about the importance of community and honoring people and their contributions.

This country is a country full of minorities that have created a lot of the beauty here. You know? I want to be more like that, a creator of beauty.

Laura: I love what you said, “I want to be more like that.” You’re a teacher…you are more like that.

Melodie: Yeah, but honestly we don’t make enough money. I don’t make enough money to have all these wonderful experiences. I feel like travel is education, it’s very important. Just the simple aspect of traveling and being in an environment other than your own, is education.

I think I’m very much a person that likes to see people empowered and people pushing their limits and trying to tap into their potential. I wasn’t doing that for myself. And now I’m starting to do that for myself. I’ve had a life of hardships and I want those days to be gone. I want to live a life of celebration and learning and exploring. That’s what I’m into now.

Laura Glazer is an artist using curatorial strategies to share exciting stories that she finds in places she lives and visits. Her work is socially-engaged and depends on the participation of other people, sometimes a close friend, and other times, complete strangers. Her background in photography and design inform her social practice, and her artworks appear as books, workshops, radio shows, zines, festivals, exhibitions, installations, posters, signs, postal correspondence, and sculpture. She holds a BFA in Photography from Rochester Institute of Technology and is an MFA candidate in Art and Social Practice at Portland State University. She is based in Portland, Oregon, after living in upstate New York for 19 years.

Melodie A. Adams is an educator with Portland Public Schools. She obtained her teaching degree at Concordia University in 2007 and is currently finishing a Master’s Degree in administration. Melodie is currently in her fourteenth year of employment with Portland Public Schools and has been at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. School for thirteen years. As a little Black girl she did not see herself reflected in her own education. She developed a passion for targeting the needs of students who have been marginalized and who have been historically underserved. In addition to leading the staff at Dr. MLK Jr. School in cultural competency training, Melodie has worked with organizations such as Courageous Conversations, Coaching for Educational Equity, and the Center for Equity and Inclusion, and has facilitated diversity trainings in school districts around Oregon. She has expressed wanting to be a change agent and considers herself an activist for civil rights and a warrior for equitable education against systemic racism.

As a young child, Melodie grew up in subsidized housing and was raised by a single mother. Melodie, her mother, and her two brothers were a close nuclear family. They grew up with a limited amount of money and resources and had to get help from her mother’s relatives more often than not. As a half Black child, Melodie tackled many obstacles growing up in an otherwise all white family. Facing the challenges of financial woes and the lack of security, she was also confronted with racism and the stigma that comes with living in poverty.

After struggling to fit in and make the most of her circumstances, she became curious about her identity and set out to search for her father’s side of the family. Eventually she reunited with her father. As Melodie wrestled with her identity and her loyalty to her white side of the family she was met with resistance. She left home when she was sixteen to fend for herself. During that time, she was able to build a relationship with her father until his unexpected death, two years later.

In the summer of 1989, after the death of her father, she found out she was pregnant with her first child; she was only 19 and her son was born in 1990. Two years later, she was blessed with a baby girl. Her children became the driving force behind her resilience. Yet the fear of history repeating itself fell heavily upon her shoulders and she did not want to raise her children in poverty. As a young girl, she dreamt of overcoming her circumstances and fantasized about becoming a lawyer or maybe a chef. She never thought it was possible. Melodie vowed to make one of her fantasies come true. She decided to apply to Western Culinary Institute in hopes to one day become a chef.

After many years of hard work in the culinary industry. Melodie realized the money she earned was not going to be enough to sustain her family. Upon suffering a back injury which led to an extensive surgery, she needed to change the course of her life. Not knowing exactly what she was going to do, she quit the industry and went back to college. After several years of prerequisites, working hard, and raising her children, Melodie graduated with a teaching license. She continues to educate herself and will always fight for her students. She is not sure what the future holds but she knows it will be in education and fighting systemic racism. Besides her educational accomplishments, Melodie’s biggest success is raising two wonderful human beings. Thank you for taking the time to read about a woman who has tenacity, an unwavering resilience, and who has become a pillar in her school community.