Public Space, Karaoke Practice, and How to Be Useful

December 4, 2022

Text by Luz Blumenfeld with Lo Moran

“I’m kind of one of those people who feels like everything is my art practice.”

Lo Moran

I have wanted to meet Lo Moran since someone in the program mentioned their experimental music project, soft fantasy, to me last fall. I was enamored by the name alone and excited to see someone who had been in this program working with sound. This Fall, Harrell asked us to interview an alumna of the program, so I took this opportunity to finally connect with Lo.

Lo Moran graduated from the PSU Art & Social Practice MFA program in 2018. Since then, they have been an artist in residence at UMass Dartmouth, and more recently, spent time abroad in Germany, where they currently reside.

The more we talked, the more connections I found between our practices, which has been really exciting to me. We spoke about their karaoke practice, how to make sense of all the different parts of your work, Lo’s work on the Art & Social Practice Archive at the PSU library, and Lo’s graduate project about block parties.

Luz Blumenfeld: What does your practice look like these days?

Lo Moran: It’s kind of spread all over the place in many different realms in a bit of an overwhelming way. But the project that’s like my pet/personal, whatever you want to call it, project I’ve been working on for the last year is a comics and audio series for Difference is a Field, which was a project I was working on in the program, actually. It’s funny, because it’s a comic that’s almost documenting what I was doing in a socially engaged art project. There’s a lot of meta qualities to it. I’ve mostly done social practice work over the last several years, but I studied illustration originally and it’s been cool to kind of come back around to that, and also kind of combine those mediums. The audio component is an interview aspect of the project. So, I’m thinking about the conceptual possibilities of comics a lot and how they could relate to my socially engaged practice.

Another big project I’m working on this term is at the Montgomery Street Plaza at PSU. They have a creative placemaking thing—

Luz: Oh, I’m actually in that class. It’s called Public Space and it’s taught by Ellen Shoshkes.

Lo: Oh wow, so Ellen invited me. I did a series of events for that project last year. And then this year, I’m combining it with the work I do in the Friendtorship class with Lis Charman.

Luz: Oh, I didn’t know you were a part of that, that’s cool.

Lo: Yeah, so I’ve been doing that since Spring 2020. It’s been mostly online, but now it’s like a hybrid, in person and online. I’m coordinating this kind of food project. It is still very much in the process of being formed, but it’s food and storytelling, and everybody coming together around food stories. We’re gonna have a collective meal together in the plaza and install these banners that are going to be up for a few weeks, I think.

Luz: Oh, cool.

Lo: Yeah, and we’re working with a middle school in Troutdale, and it’s kind of about what they want to bring and see in downtown Portland. They actually chose food as the theme. And then we were like, okay, how can we use this to connect and have them do storytelling and do art works around it? So that’s a project that’s developing right now, and that kind of goes with teaching.

I’ve been doing a lot of workshops. I worked on another thing with teenage girls and public space here this summer that was called Gendered Urban Landscapes (GUrL) by Carmel Keren. So it’s about teenage queer people and girls and how they interact with public space. That wasn’t my project, that was in collaboration with somebody else. I also did a food project here recently. I feel like I’m always doing a lot of different things and then trying to interconnect them.

I also work with a collective here that’s around accessibility and disability. And I was doing something kind of similar when I was in Portland, that has gone on without me, which is nice.

Luz: What is that?

Lo: It was called Public Annex. We kind of disbanded, but then I helped the new group, which is called Elbow Room, and we gave them all of our money and our nonprofit status, and I helped them all get jobs. I had my place where I was a support provider for folks and so that kind of helped with the sustainability of the project, because with Public Annex, we were doing it all, mostly volunteering, and then occasionally getting paid for different projects. Elbow Room has a space now next to the IPRC (Independent Publishing Resource Center). Somebody donated the space to them for three years, so I think they’re doing really well.

I always take on too many projects and they’re always in completely different directions, like archiving, teaching, comics, and I’m working on a LARPing related project. That’s my fun thing. Performance is also an aspect of what I do, with a lot of karaoke related things.

Luz: Tell me more about your karaoke practice!

Lo: I became obsessed with karaoke actually when I joined the social practice program because I was just really rusty and inexperienced with giving public presentations. I just kept bombing and getting really, really nervous. Karaoke was a way to try to get more comfortable being in front of people because I was also starting to teach a lot more, but then it just turned into a karaoke obsession, but like, as a socially engaged art form. I think it’s a really unique space that brings together lots of people that wouldn’t normally come together. It’s accessible, but you can get pretty weird and creative with it. It’s like singing together, which is something that people have historically done in religious spaces. It really brings people together in all sorts of strange ways.

My first karaoke project was when I was the artist in residence at UMass Dartmouth. The first year students and I started a little karaoke club and it was really nice. It was a good starting point for getting to know each other.

I did this project called Karaoke for the Revolution that was like, pop-up, guerilla style with social justice themed songs and playlists. Now, I actually work as a karaoke DJ here at a giant karaoke club. I’m there once a week in front of hundreds of people. The space is very drag-oriented and there’s a lot of really cool performers. I’m taking it slow and learning all the tech. They said I could eventually start hosting my own events and I’m hoping that will grow into more of an event series.

Luz: Yeah, that’s so cool. So are you planning on staying in Germany for a while then?

Lo: If I can survive. I have a three year residence permit, so I’ll see what it’s like.

Luz: How long have you been there now?

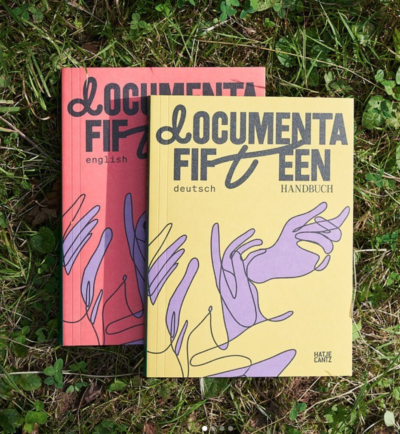

Lo: Since January, and I was only planning on staying three months at first, and then it just snowballed. A lot of projects came up here and I was like, oh, I really want to stick with this. I worked on some projects this summer for documenta, which was this really big art festival that was all social practice projects this year. And what else did I do? Oh, I had an album for my music project that I was putting out here. So it kind of just turned into a thing where I could stay. I was at an art residency that was also all social practice and that was really nourishing and healing after the pandemic isolation. I was living with 15 other artists and I was working on the comic there. So those are some things I’m working on here.

Luz: That’s awesome. That’s so many things I love.

Lo: It’s kind of like a problem sometimes.

Luz: Yeah, but I get it. I feel the pull as an artist, and especially as a socially engaged artist, by so many different interests that sometimes intersect but sometimes don’t. And sometimes there feels like an urgency behind them and I just need to follow that.

Lo: Yeah, Harrell really helped me with that because I would be like, how are all these things related? Will they make sense when people look at my practice? And he was always like, well, you’re the person that connects everything, so just go with that. He said, “You have to just trust that there is a through line.” And I really see it now. Like, I do see all the interconnections between all the disparate things.

Luz: What was your grad project and how did you come to it throughout your three years in the program?

Lo: I was kind of overambitious and I originally tried to do this project that I made into a comic called Difference is a Field. But I realized it was way too big to try to do as a grad project and I’m still working on it years later. So I did this project that was called Scores for a Block Party which actually kind of spanned my whole time in the program. When I first moved to Portland I was really struck by the housing crisis happening in 2015. I had never lived in a place that was going through so much gentrification. I know it’s happening everywhere but moving to Portland I thought it was so extreme.

I proposed a project in my neighborhood to get a RACC (Regional Arts & Culture Council) grant and they gave it to me. It was the first time I had ever gotten a grant for an art project. Housing was so unstable then that by the time I got the grant I was already living in a different neighborhood. I was terrified, I was like, what do I do? I live across the city now. And people were like, you can just tell them you want to change your project. So I started doing research in the new neighborhood I was living in and my research was walking around and talking to people. I saw a flier in the community center about block parties. My other project in the other neighborhood had been about creating a gallery in an alleyway. So I was thinking about how block parties are very anti-capitalist and how the only reason for them to exist is because people want to get together. It’s a space that’s rare these days. When it started, I was thinking about art happening at block parties and I was really into the idea of scores and instructional art. I partnered with this community center up the street from me that was having a block party that summer. So my idea was to get to know the neighborhood and the people in my neighborhood through this project. It ended up being a block party with four different scores that were enacted by artists, and two of the four were actually artists from the neighborhood. It was this range of scores from artists in the neighborhood, local artists, and international social practice artists.

Image ID: Photograph of a community gathering under tents with text overlaid that reads,

“Free Pile Sculptures: A Score by Madeline Sorenson,” among other details of scores. 2017.

Portland, OR. Photo by Lo Moran.

Luz: Which neighborhood was this in Portland?

Lo: The Vernon neighborhood, next to King, close to Alberta.

There was a whole block party department at the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBoT) that I got connected with and I was invited to be the artist in residence there. I made a book about the project and the next summer I took the book and we enacted five different block parties and people chose which score they wanted to happen. Then we recreated them, all of the different block parties all over the city. It was interesting.

Luz: I’m very interested in spaces like that, spaces that are specifically not capitalist spaces. That’s why I wanted to take that Public Space class, because I’m really interested in how public spaces have transformed under late capitalism. With so much rapid gentrification in so many cities, like the Bay Area, where I’m from, you start to see all of these “Privately Owned Public Spaces” that are not actually public legally because they’re owned by corporations, but they exist in spaces that should be public, like the space between buildings. There’s a lot of policing and hostile architecture in those spaces.

I’m interested in seeing what WPA projects are left in our cities because a lot of those were designed specifically for pleasure or leisure and not for any kind of productivity or profit and it’s so rare to see that today.

Lo: Yeah, public space is so different here. There’s so much, there’s so many little parks in every neighborhood. There will be a little park with a playscape and ping pong tables or a green area. It’s very impressive how they use public space in Berlin.

Luz: That’s interesting because coming from Oakland to Portland I was so impressed by how many parks there are here. It seems like almost every neighborhood has a park, which is not how it is in Oakland at all.

Lo: Yeah, here is even a step up from that, I would say. There are community centers everywhere too. There’s much more of a socialist history here so it’s just much more present.

Luz: That’s really cool. Do you think you’ll get involved with using those spaces for projects?

Lo: Yeah, the youth project I worked on this summer was about how youth interact with public space here and I might work with that youth center again. I also live right next to a high school and I have dreams of working with them.

Luz: That would be rad. I want to talk to you about the Art & Social Practice Archive at the PSU library. What is exciting about it for you? How did you get involved with it and why are you still working on it?

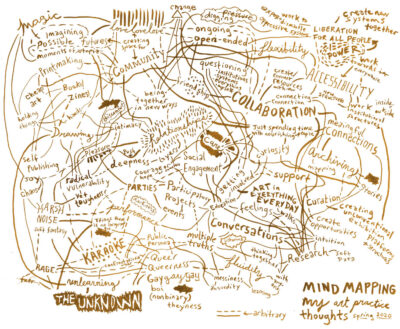

Lo: In my last year of the program it was the 10 year anniversary of the Art & Social Practice program. Harrell was starting to talk to the library about the Special Collections and what if we created an archive there. It was a really interesting process to develop it. My interest came from publications because I’ve always been a publication person and like, a print nerd. I realized that I’m an archivist; I’m a person who collects little pieces and scraps from everything and has a hard time getting rid of them. My personal archives are a mess, but now I can give stuff to the library.

Luz: So how did the archive start?

Lo: We had this initial batch of materials we collected for the physical archive in the library. It was very non-traditional for the library. They’ve mostly done historical archives where they get it all in one chunk like a bunch of newspapers from the 70s or something. But they agreed to let it be a living, growing archive. So we were learning together.

The library doesn’t usually lend archive materials out, so we made it so that ideally we would have two copies of everything. So we can have exhibitions and put some of the copies on display or loan them out to exhibitions in the future.

I don’t know how I took it over, I just started doing it. I started working with student interns because I thought it was a really good opportunity for students to get archive experience. There aren’t many ways to get archive experience and I want to make it accessible to students. I tried to make it useful for whoever was involved and focus on their interests. So if they were interested in a particular artist, this was a way to reach out to those people directly too. There’s so many ways, so many directions it can grow into, which feels a bit overwhelming sometimes, but also exciting. It feels so small right now. There’s so many more artists we have to collect things from.

In 2020, I was really interested in the digital archive and it took almost the whole year to just get it started. There’s so many layers of people working at the library digital archive. The pandemic hit and suddenly everything had to be remote and online, so it was perfect. It was very fateful because we were already setting up this digital archive and so that became what we focused on for the next year or so as the pandemic went on.

We didn’t take that many physical submissions again until last year. But now the digital archive is built and it can be added to really easily.

One of the things I found exciting with the archive recently was that I got to collect a bunch of stuff from documenta during their social practice exhibitions. I visited the documenta archive and that was really cool to see. They’ve been around since the 60s and it was huge and just a really cool archive.

Luz: How do you explain social practice art to people who aren’t artists?

Lo: I usually say I do art that’s collaborative and working with people in communities. It’s working with artists and non-artists to make art projects in public. And then people usually say, like murals right? And I usually say, sometimes.

Luz: Yeah, I like that. I feel like I’m coming up with it every time someone looks at me blankly when I say that I’m in an MFA program for Art and Social Practice. But lately I say that social practice art is art that is social in nature, often collaborative, and more concerned with experience than objects. Not that objects or materials are never involved, but it’s not exactly a studio based process.

Lo: That’s a good way to say it. I like that way of explaining it.

It’s been interesting in Germany, like the documenta archive made me really realize that it’s so much more integrated here. They don’t necessarily call it social practice, but there’s a very long legacy of social art here, like with Joseph Beuys, and social sculpture.

There’s a lot of social practice happening everywhere here in an interesting way. I didn’t expect it.

Luz: I think that somewhere with such a socialist history— it makes sense that there would be a lot of it there.

Lo: Yeah, that’s true. The place that I was doing the art residency at was involved with documenta. I think there is a sense of it being, not marginalized from the art world, but like it would not be a part of one of the biggest contemporary art fair festivals in the world, you know? They were still kind of surprised that it was all social practice art this year.

Luz: Yeah, I would love to see more of documenta.

Lo: You can at the archive! I got all the publications and brought them there because I felt like people needed to see them. I was very excited.

Luz: How has the way you think about social practice art changed since you’ve been in the program? What has been on your mind lately?

Lo: I’ve been thinking a lot lately about when socially engaged art is useful. I’ve done a lot of activist related things and art things and sometimes I try to smash them together and sometimes not. I’ve been thinking about when it makes sense to do an art project or when it would make sense to just do something very practical, or how you can combine those things in a way that is still useful to people and sustainable, in that it won’t just be dropped after the project is over.

Sometimes I see that play out and it’s frustrating to me. I’m thinking about how it can be sustainable and if art is always the answer to that or if sometimes it’s just about supporting people or doing the dirty work that nobody else wants to do.

I feel like that has been a through line of my thinking in the last few years, especially through the pandemic. How to be the most useful in different situations. Sometimes that was supporting artists, but sometimes not, you know?

Luz: Yeah. Is there anything that you maybe wouldn’t consider art that is still part of your practice?

Lo: That’s a good question. I’ve gone back and forth about that actually because I’ve done a lot of work supporting other artists and I’ve been really interested in care work and how to think creatively about that. I’ve been doing social experiment workshops about that. But I do still see that as part of my art practice too. I’m kind of one of those people who feels like everything is my art practice.

Luz: Yeah, me too.

Lo: Even when I’m doing something activism related it’s usually using the skills I can bring to the table with my art, like I’m doing illustrations for a zine right now about all the problems this activist group had that they’ve summarized into a workbook to try to help people avoid them. So that feels like it’s still art, I don’t know, yeah.

Luz: Is there anything else you wanted to say that I didn’t ask about?

Lo: Artists should be paid more! And teachers, too. But also, how can we rebuild these systems that aren’t supporting us? I wonder a lot about that.

Luz Blumenfeld (they/them) is a transdisciplinary artist and educator, third generation from Oakland, California, who currently lives and works in Portland, Oregon, where they are a second year in the Art and Social Practice MFA Program at Portland State University. Luz wants their work to invite you to slow down and give attention to small things and to consider our relationships with them. They are currently giving attention to what signs their preschool students think the world needs, voicemails from grandmas, and the water in the San Francisco bay.

luzblumenfeld.univer.se + IG: @dogsighs__

Lo Moran (they/them) creates interdisciplinary work that is often socially engaged, participatory and collaborative. They aim to experiment with and question the systems we are embedded in by organizing situations of connection, openness and nonhierarchical learning. Projects act towards accessibility and reimagined ways of being together through personal investigation of community support and belonging. They are currently working on a comics and audio series based on examining interactions with people of opposing ideologies, experimental music performances, and an archive of socially engaged art ephemera. Lo has also been involved in creative initiatives within disability communities for the last ten years. They try their best to embrace fluidity and chaos to contribute to emergent futures and radical approaches.

LoMoran.com and IG: @_lo_and_behold_