Tethers

February 20, 2019

Text by Elissa Favero

On the second day of the year, I learn that my sister has been diagnosed with thyroid cancer. She’s over 1,700 miles away, in Chicago. She announces the news to our family over text. And though she and I will speak on the phone occasionally in the next months, most of the updates ahead will come via Short Message Service (SMS). Some reflect her lawyerly training—informative, succinct, definitive in the face of uncertainty. Others—many others—are silly. As she plans for the isolation her radiation treatment requires, she writes of her Laura Ingalls Wilder preparations, of the supplies she had gathered for her time of hunkering down, her “nuclear winter,” as she’s calling it. Her partner, fortunately, is able to stay in their condo but has to relocate his bed to the couch. She can’t be within three feet of him or anyone else for eleven days. She’s played The Police’s “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” for him the day before she begins treatment, she tells us. On the fifth day of the isolation, she writes, “At least the treatment seems to be working.” In the picture she attaches, her face glows green from the reflected light of the computer monitor beneath her face. In response to these messages, my Mom writes from Maryland with dogged optimism and over-the-top, animated emojis. She’s 600 miles from my older sister, some 2,300 miles from me in Seattle. My younger sister, in Baltimore, is quick, wry, just as she is in person. My Dad is earnest, self-deprecating, obviously deeply concerned. “That is good news,” he replies to my older sister after an early report with some bit of encouraging information, some mitigating detail. “You are in my heart as I travel,” he tells her, and us, on his way to visit my grandmother in Montana.

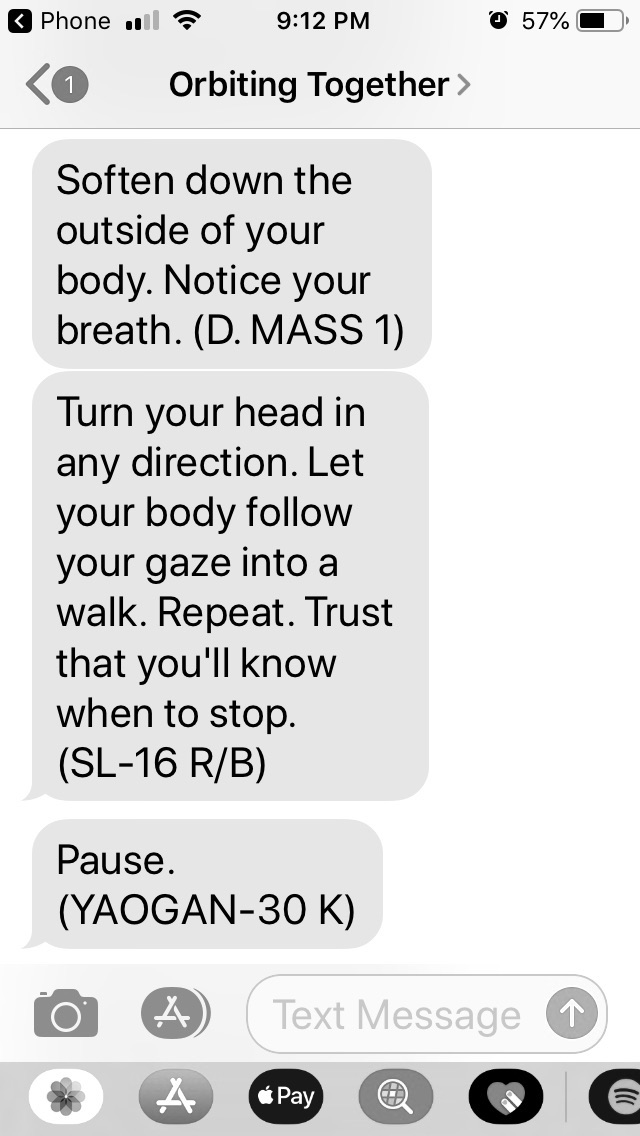

Later that month, I subscribe to a series of SMS notifications. These come daily, sometimes twice a day. Each is an invitation to participate, from afar, in a winter program at the Seattle Art Museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park. Orbiting Together begins with a low-stakes prompt on January 26: “Recall which pair of socks you chose to wear today. Observe how they feel on your feet. How long have you had them? (NAVASTAR 71: USA 256)” I try hard to remember before lifting my pants leg to reveal rose-patterned knee-highs. They were a Christmas present from my older sister the year before. I think of how many others are receiving the message, trying to recall their wardrobe choices of a few hours before, wiggling their toes, stealing glances down at their feet.

—————————————–

Tia Kramer, Eric J. Olson, and Tamin Totzke composed the daily notifications for Orbiting Together in response to the paths of satellites traveling above the sculpture park. Some three thousand pass over the park each day. These satellites, part of the United States Air Force’s Global Positioning System (GPS) that launched in the early 1970’s to track and transmit data about time and location, make it possible now for us to pull out smartphones, swipe and tap, and find exactly where we are. They make of geography something exact and objective. The cell phone messages the artists use, meanwhile, are conveyed to us by way of towers communicating at different radio frequencies. Like the satellites, the towers transmit at a distance. Even nearby, these satellites and towers often go unnoticed, the visible/invisible infrastructures that allow for our digital lives to play out via screens sensitive to touch.

The messages ask me to pause and engage. The artists meant to co-opt the contemporary technology of digital capitalism and subvert it. They want to draw us back into the reality of what’s passing overhead or nearby, to our own bodies and feelings. The information they convey is the action of a passing satellite. The rest is suggestion—the prescribed action up to me.

More often than not, I admit, I imagined instead of enacted. My favorite prompts—the ones I was especially likely to follow—ask not for physical engagement but for more basic awareness and perception. “Listen for a rhythm in your environment. Consider your heartbeat.” came the prompt late afternoon on January 31. I listen to the hum and horns of I-5 traffic outside my window. I can’t hear my heart, so I put my hand to my chest and find its rhythm. Where, I wonder, does touch become sound? This particular message corresponds to the BEESAT-2, the Berlin Experimental Satellite that allows for amateur radio communication.

Ten days later, I hear my phone buzz and reach out for it, reading “Look to the satellite flying overhead. Cup your hands around your mouth and whisper a message to someone who is very far away.” The corresponding IRIDIUM satellite, I learn later from the artists, provides satellite phone coverage for people in remote locations.

I think of the main character in the 2001 Hong Kong film In the Mood for Love. At the end of the movie, Chow Mo-wan comes from Hong Kong to the ruins of Angkor Wat. He has earlier told his friend about an ancient practice of making a hollow in a tree, whispering a secret inside, and covering the opening with mud. In Cambodia, Mr. Chow touches his hand to a space in the temple wall before bringing his mouth to it. After he leaves, we see that he has stuffed straw into the void, pushing back his words as far as he can reach. The words themselves we never hear. As he stands, leans, and whispers, the film’s music swells and the camera circles, a satellite around him.

—————————————–

In-person, participatory performances bookend Orbiting Together’s month of daily texts. At the first, I feel my introversion as I arrive and survey the scene from the edge of the room. I’m relieved when we’re called together, coordinated into movement. Weeks later, at the start of the second performance, a woman asks for my arm as she adjusts her shoe. At once I feel helpful, more at ease. About halfway through the performance, a prompt directs us to “Sink into the floor and allow yourself to be held by those around you. Notice how you are holding up others. (SL-14 R/B)” I laugh with the three people I happen to have been near and fallen with. We are preposterously, precariously arranged, backs on the ground with limbs extended, overlapping, supporting or being supported. I’m being stretched past the polite disregard I cultivate on the bus and in other public spaces.

At this second performance, there are professional dancers among us. They perform with us and then coalesce to extend the directives with the grace of bodies professionalized for movement, becoming fonts of trust and mutuality in a sea of strangers who’ve been asked over the course of these weeks leading up and now this evening to come closer and closer. “Feel the presence of others. (WISE),” we are directed. “Fall with someone. (D. MASS 2)…Notice your hesitation. Notice your surrender. (ALOS: DAICHI)” And later, “Orbit around somebody you don’t know. (SAUDISAT 1C: SO-50)…Observe your heartbeat. (FENGYUN 3C).”

—————————————–

All told, 422 people subscribed to Orbiting Together’s notifications during January and February. Many also posted to an Instagram account, documenting their responses to the daily prompts through photographs and short videos. I’m struck as I scroll through these that the participants aren’t touting the beauty or good taste we’re often meant to see in selfies or vacation photos. Instead of assertions of individual identity, the responses feel more like a chorus of gentle echoes. So this is what it looks like when you spin in place, noticing your dizziness, imagining satellites travelling faster as they get closer to earth.

The artists behind Orbiting Together conceived of their project as a rhizome—in botany, a system of roots that extends laterally, without a clear center. “This project,” they write, “uses a network of satellites flying over the Seattle Art Museum Olympic Sculpture Park as triggers for messages encouraging participants to engage their somatic awareness. Individuals opted into the system create a rhizomatic positioning system composed of people in the place of technology.” The Olympic Sculpture Park is the nexus of activity, with satellites passing overhead, triggering the messages. But the recipients and enactors themselves define the network, its reach and shape morphing and mutating over the weeks. In their book A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari similarly use the metaphor of the rhizome to put different disciplines in conversation and send out reverberating lines of communication. “All we talk about,” they write in their introduction to the book, “are multiplicities, lines, strata and segmentarities, lines of flight and intensities, machinic assemblages and their various types…It has to do with surveying, mapping even realms that are yet to come.”

We orient ourselves relative to people, to a constellation of relationships both casual and serious, immediate and distant. These comprise single exchanges, rapports formed by routine, brief periods of intense intimacy, and bonds that will last a lifetime. These relationships help tell us, in big ways and small, who we are and how we belong together.

This last year and a half, I’ve experienced the remote sickness and recovery of first my father-in-law and then my sister. In the last month, I learned from a friend across the country about the sudden, devastating death of her husband. Perhaps the reverse side of Deleuze and Guattari’s underground, extending roots—always expanding and coalescing, spontaneously forming—are the ways history and shared experience have tethered us to each other. “Tether” comes from Old Norse, meaning “a rope for fastening an animal” and, by two centuries later, the “measure of one’s limitations.” We are, in a sense, beasts of burden to one other, figures of responsibility and obligation. But instead of selves bounded and begrudgingly beholden to each other, I think of Deleuze and Guattari’s multiplicities and intensities moved above ground, those communications via satellite and text, those tracks and tethers that allow me to feel the pull of my sister, my father-in-law, my friend, the tug I perceive at my end, the connection that reaches between them and me and measures the length of the distance and also forms its link.

The rhizome: a ribbon of highway ceaselessly carrying drivers and passengers near and then past my window; an arm extended to a stranger when she needs it; and a happenstance, precarious pile of laughing bodies on the floor of a museum. And the tether: the teasing and self-deprecation and, at the best of times, vulnerability and fierce love that took years to bloom between us, that I want to tend across miles and years.

My sister and I will likely never live in the same place again. There are good reasons for that—differences in professions, interests, temperaments, values. Sometimes these can feel like vast chasms. It can be hard to say the right words to each other. I know I’ve said the wrong ones, said what felt like betrayal, heard what sounded like indictment. Or said nothing at all. I feel the tug, though, of her typed texts or animated gifs on my end and I tug back. We orbit together in a perpetual dance of distance and immediacy, uncertainty and intimacy.

Connections, though, can be cultivated, can extend into territory as yet unmapped. Toes and heartbeats and whispers to ourselves, observations from a window or a proffered arm or bodies right close to each other, calls and texts with those we love already: these are the realms of self-awareness and friendship—however temporary or lasting, however unexpected or made of what we think we already know so well—that pulse with the present, that are, in Deleuze and Guattari’s words, the realms ever yet to come.

I look up. I reach for my phone.