“The Bravery to Claim this Country as One’s Own”: How the South Asian American Digital Archive Stakes a Claim on American Identity, Freedom, and Joy through Sharing Road Trip Photos

March 18, 2024

Text by Nina Vichayapai with Samip Mallick

“Archives are where our stories are created. They are how we understand our own past, how we understand and connect with each other today, and the basis for how we foresee the future.”

– Samip Mallick

My family has a sizable collection of road trip photos taken shortly after my parents immigrated to the United States in the 80’s. If ever there were a house fire, these photos would be the first thing I would grab. In these aged film photographs my Southeast Asian family are often the only people of color in sight. As I grow older, I realize that the preciousness of these photos is partly due to the rarity of seeing a family of color boldly stake their claim to leisure on the open road. Despite personal experiences with road trips that I and many other families of color share, an overwhelmingly white narrative continues to dominate the idea of who gets to freely travel America’s roads.

This disconnect between road trip reality and myth is precisely what prompted Samip Mallick to start the Road Trips Project. This archive shares submitted photos and stories of South Asian Americans on road trips. Accompanying the often sunny photos is a map of the route taken by the individual or family, along with memories of the trip. Clicking through the thoughtfully compiled archive brings me right back to the feeling I get upon looking at my own family road trip photos–a deep sense of nostalgia and hope for the road trip canon to be reframed around images like these instead of the whitewashed version of American travel familiar in the media. To understand his motivation in creating this specific and incredibly important archive, I spoke to Samip to learn about the origins of the Road Trips Project and the importance of archiving the South Asian American community.

Nina Vichayapai: To start, could you give a background on what the South Asian American Digital Archives (SAADA) is?

Samip Malick: SAADA is an organization that works to create a space of belonging for South Asian Americans: a community of more than 6 million people that has typically been overlooked and excluded from the American story.

We do our work by collecting, preserving, and sharing stories of South Asian Americans, stories that date back for hundreds of years, and that help South Asian Americans to recognize themselves as an essential part of the American story and to write South Asian Americans into the American story as well.

Nina: One of those storytelling projects is the Road Trips Project. How did the Road Trips Project begin?

Samip: The Road Trips Project was inspired by a tragic incident that took place in 2017. Two Indian immigrants in Kansas were at a bar having a drink after work one day, and a white man walked into the bar and shot them. He killed one of them, Srinivas Kuchibhotla, and seriously injured the other, Alok Madasani. Before shooting them, he said, “Go back to your country.” That refrain, “go back to your country,” is one that many immigrants of color hear, often before some act of bigotry or violence is done against them.

The Road Trips Project works to interrogate what it means to feel othered or foreign in a country that either you’re born and brought up in, or that you made your home by choice. And it really helps to think about what it means to be able to travel across one’s own country, safely and without fear of harassment or intimidation or violence.

The Road Trips Project shares stories, joyful stories, of South Asian Americans traveling across all 50 states of the United States. In doing so, it helps to reframe an American tradition, the tradition of the road trip, which claims that Americans should be able to get in their car and drive across the country at any point, and really helps us think about what that means for communities that have been excluded from that narrative, and that have also been targeted or excluded from being able to feel safe in country they call home.

Nina: Do you have a favorite story or moment that came out of this project?

Samip: One that sticks out in my mind is a story of someone who was traveling in the American South who walked into a bar, expecting the kind of othering or response that I was describing, but ultimately found themselves incredibly welcomed in that situation. There are stories that go against the narratives or stereotypes that one might feel but that really, ultimately, are about acts of bravery—the bravery to claim this country as one’s own.

Nina: Can you explain more about what goes into managing this particular project? How are stories collected, mapped, and shared?

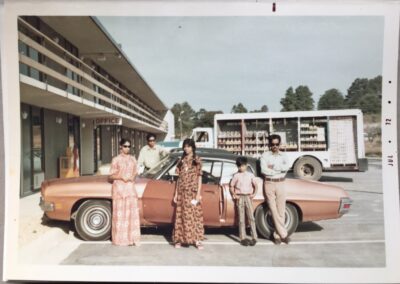

Samip: People submit stories and photographs of themselves traveling on road trips across the country. Typically, they’ll submit a photograph and along with that photograph, they’ll share where they started the road trip, what their destination was, where and when the photograph was taken, who they are with on the road trip, and an anecdote or a story either about that particular location or about the road trip as a whole.

These photographs are often dripping with a kind of nostalgia—they have this sepia tone or colors that are so reminiscent of the 80s and 90s. The stories are also reflective of people’s memories and their occasions with their family or their friends or even on their own. All these stories are aggregated and shared online through the Road Trips Project website.

Nina: What does the Road Trips Project mean to you? What do you think is the value in offering this project to the world?

Samip: I think the value of the Road Trips Project is to help people really think about the freedoms that they take for granted: the freedom to travel in your own country and what that means, and how that freedom is determined by things as fundamental as your gender identity, the color of your skin, where you were born, or how you speak. To think about who is excluded from those particular freedoms and about how to make them more inclusive, how to make sure that the stories that we tell about ourselves in our history are inclusive of people that are otherwise excluded from them. By creating this project, our hope was really to reframe a fundamental American mythology and tradition. When you hear about stories like Jack Kerouac’s writings about traveling across the country, or so many others, those stories are not typically of immigrant communities, communities of color, or South Asian Americans. Through offering the Road Trips Project, our effort is to help write South Asian Americans into that story.

Nina: Through the work that you’ve done over the last 15 years, can you share why archives are important to the South Asian American community?

Samip: Archives are where our stories are created. They are how we understand our own past, how we understand and connect with each other today, and the basis for how we foresee the future. For a community like the South Asian American community that hasn’t been typically reflected or represented in archives, has meant that those three things have been missing for us. I think archives have been fundamentally important for us to really see our own past, present, and future but also, more importantly than that, understand how we are a community to begin with, and how we connect with one another.

Samip Mallick (he/him) is the co-founder and executive director of the South Asian American Digital Archives (SAADA), which he has guided from its inception in 2008 to its place today as a national leader in community-based storytelling. Mallick’s background includes degrees in computer science and library and information sciences and work related to international migration and South Asia for the Social Science Research Council and University of Chicago. Mallick currently serves on the Library of Congress Connecting Communities Digital Initiative advisory board. He also previously served as an archival consultant for the Ford Foundation’s Reclaiming the Border Narrative initiative and on the Pennsylvania Governor’s Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs.

Nina Vichayapai (she/her) is an artist whose research excavates for signs and representations of belonging in the globalized world around her. She explores what it means to belong within the American landscape for underrepresented communities. Born in Bangkok, Thailand, she graduated from the California College of the Arts with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 2017. Nina currently lives in the Pacific Northwest.