Touch the Things, Make the Sounds

December 12, 2021

Text by Laura Glazer with Elsa Loftis

“I would love to have that integration of classroom space, studio space, and library space all in one. And that might be like a completely difficult thing to realize, but I think that I always want the library everywhere.”

ELSA LOFTIS

During my first year in the MFA program, I tried using an art studio on campus. I filled it with my favorite supplies, inspiring books, and uncluttered surfaces. But when I was there, it did not feel vital to my practice. I relocated it to another room with a huge window, hoping that it would be invigorating to see activity outside. Instead, the studio remained quiet and lonely, with few opportunities to respond to the place.

When Elsa and I talked for this interview, I was captivated by her vision of including spaces for art studios in the library, and I imagined relocating my under-utilized studio there. But even in my daydream, it still wasn’t a place I wanted to go. So, I started constructing a version of what a studio in the library might look like for me as a socially engaged artist: no walls, doors, or desks. Instead, there is a large table near the existing library study carrels and stools on wheels tucked under it. Nice paper and pens are available for free, and a special stapler for making zines is nearby. And anyone using the library is invited to sit down and work there. When we need inspiration or have questions, we can explore the books in the stacks and collaborate with Elsa.

This vision of a public art studio reveals an evolution of my creative practice, going from creating a private space that didn’t feel right, to envisioning a public space like the library as a studio space, and shaping it to respond to that site. This ideal place is not a space where I work in isolation. Rather, it is a large desk with space for me and other people to work, study, and create together; it is a place to be social in public.

Laura Glazer: I was trying to figure out a good place to start and what came to mind was how I’m haunted by something you said in our conversation last August. I have this really clear vision of what you described at OCAC(1), where you would have a pot of coffee and students would come in all the time. But at PSU, you were saying it doesn’t work at this scale. And you said, “I need help inserting myself into their practices.” Where are you with thinking about that?

Elsa Loftis: You know, I always feel re-invigorated when I’m able to do the instruction sessions because that’s when I start to get contacted by students. You know, when I get in front of them, and I do my little dog and pony show: here are the databases and this is why they’re so useful and look at all of the fun things you can look for and find. And then I will get emails after that from students who say, “oh, you visited my class and I’m doing this.” Then I get excited about the actual connection between working with people who are seeking information and hopefully assisting. And that’s the person-to-person stuff that I really enjoy. And that’s difficult because I’m waiting for people to kinda come to me. Whereas I would like to just sort of be out wandering around and saying, “Oh,” you know, “how are you today?”

I think very much about the library as place. The library is symbolic in many ways of a place for information. It’s a place to have solace and quiet and reflection, but there’s also kind of this element of, it’s a place to be. It’s a brick and mortar building and that is more or less important now than it ever has been.

I guess what I’m trying to say is, the library is definitely more than just what’s inside the four walls, it’s absolutely more than that. Not only because of our electronic resources and things of that matter, but it’s also kind of a headspace. It’s sort of a way to think, reflect, and work. But it’s also just the actual challenges of the proximity of where I am; in my past lives in other libraries, my office was sort of right out there where students were running around. So, if someone had a confused look on their face, I could just intercept them at their point of need. And where I am now, my office is in the cataloging and acquisitions space, which is behind locked doors so I have to actually physically leave my office to go look for students.

So that’s just a way that the space is elemental. And just having the energy of the people around me when they’re in their seeking phase of their research.

Laura: What does it mean to be an academic librarian?

Elsa: It’s a good question. It just means I’m a librarian in an academic setting. I’ve worked as a public librarian before, so that was a different experience. I mean, it’s not that different in a lot of ways. It’s a service orientation and you’re a public servant, you are meeting different needs in different spaces so you adjust your pedagogy or your workflow. You certainly are dealing with different kinds of collections. The range of people that you meet is certainly a little more narrowly defined in an academic library setting. Although most of the time we’re open to the public. Although we aren’t currently open to the public because of the pandemic. But we do offer spaces for the public to come in and share our resources and share our space. The PSU motto is “Let knowledge serve the city,” so we take that very seriously. We have that as an important role that we play, to offer information and services to people that are beyond our community.

And we also are a government document repository library. People need access to their government information and we provide that.

Laura: Where is the ideal space for you to work in? And it can be in a magical world!

Elsa: I think that in my magical world, the library is in the center of campus, in the heart of the physical space that students inhabit. I would love for there to be studio space in the library. In fact, I used to experiment with some of that.

I would try to put small little pop-up library collections in the studio spaces so that people could have reference resources while they’re throwing pots or welding things. [Laughs!] And when we did that, it was difficult to gauge the engagement with the resources, because a lot of times there’s no way to really track usage if it was just sort of like, Here’s some stuff you could look at it, you know, go nuts.

When you’re trying to work with students and getting folks to get engaged with your materials, you just throw stuff against the wall and see what sticks. We used to do those little pop-up libraries—these little mini curated things—and I thought that was really nice; I wanted people to be able to have access where they were. Not have to be like, Now I’d like to venture over to the library and look at some different examples of what I might be thinking about doing right now as I’m sitting here in the studio.

I would love to have that integration of classroom, studio, and library space all in one. And that might be a completely difficult thing to realize but I think that I always want the library everywhere. [Laughs]

Laura: That is a beautiful quote! “I want the library everywhere all the time.”

Elsa: Well, because I want people to feel like they own it. I think that libraries can be daunting spaces. When I talk about the library as “place,” that’s often very loaded, I think, for some people. I think of libraries as sanctuaries and places to explore and places to go on these adventures. And I think that maybe not everybody feels that way. I think that sometimes they can be sort of vaunted spaces. They’re sort of cold and quiet and maybe you don’t feel like you belong. If there’s one thing I want is for students to have agency over their library, because it is their library.

Elsa continued: We’re not here for any other reasons; we’re here for service. You want to humanize it, familiarize it and make it feel like their workspace, not as some sort of museum or a place where they aren’t supposed to touch the things or make sounds. That can be loaded in a way because I think the library as place is very important and I think that research can be done in so many different environments and formats. You can do a lot of research online; people are very good at doing research online. We’ve spent a lot of time here creating a lot of learning objects(2)(3) and ways that you can access materials virtually, and you don’t have to be in the library, but I also think that the space is important.

And again, that really depends on what kind of learner you are and how you like to interface with things. But I think one of the nice things, and especially for art students and art practice students, is that element of research that’s that really kind of almost haptic practice of research, like you get in there and you’re engaging with physical materials.

For some learners that’s really a big element for their practice, for their understanding: how you process things—physically and mentally—and work that into your creative practice.

And then there’s also that kind of iterative feeling of being in the lobby. You start… it’s like you search and you research, there’s this cycle. It’s not just searching, it’s re-searching. You keep coming back, you keep doing it again. And for some makers, it’s that kind of repetition.t’s that iterative process of research and it being a discipline, you approach it in a disciplined way. And that’s evidenced in a lot of different, physical practices of making art, too.

That’s what I also like to relate to people, is that the parts of the brain that you’re using when you’re doing research are creative parts of your brain. It’s part of art practice, too. You’re using those same kinds of problem solving connectors, the same little parts of your brain light up when you’re doing research as when you’re creating things. And I think that that’s a really useful way to look at it because it’s creative problem solving, just like you’re doing when you’re making work.

Laura: Where do you land on reframing the concept of research for a studio artist and a non-studio artist like myself?

Elsa: Well, it’s a really good question and it’s a really important issue. I think that all over the academy, not just in the arts, we are asking ourselves these questions and mostly from the library’s perspective: what do we collect and what voices are being centered; what voices are being left out; who is considered an expert in their field; what’s considered scholarship?

There are a lot of silenced voices in that narrow definition of what constitutes scholarly research and those definitions are opening up. We see this now and it’s our job as the library to be on the front lines of that and leading that, and collecting and valuing and centering—I don’t want to say alternative research, or maybe just non-traditional resources, I suppose—narrative things and people with learned experience and lived experiences, being thought of as experts, not necessarily attaining some sort of degree that makes them all of a sudden worthy to hear and listen to.

So, for a studio artist and a non-studio artist, I think that those paths are somewhat parallel. But it’s also difficult to wedge that into a traditional expression of scholarship. If you were doing a research essay and you needed five peer reviewed sources or X amount of primary sources versus secondary sources, and this is how you format your bibliography, it can be a little bit daunting to put this sort of non-traditional research into a traditional kind of scholarly product. I think that our instructors are more open than ever to that. You could speak to that better than I could. Do you feel that that is something that’s encouraged or at least tolerated?

Laura: I don’t know yet. I’m really taking my first class outside of the School of Art and Design this term in the History Department where I’m taking a class on museums and memory. We have to write a research paper, which I haven’t done since the nineties. [Laughs] So I am looking at the list of requirements, like six primary, secondary sources and thinking, huh, how can I bring the lens that’s relevant to me as an artistic researcher to this requirement? And I’m in a pretty good dialogue with the instructor. I want to be careful not to push her too far because I think she’s more traditional in how she approaches research papers and so are my classmates, but that doesn’t really work for me cause that’s not what I want to produce. I guess in undergrad, it was very traditional, very structured and I just didn’t do it.

Elsa: Well, you’re not alone in that. I think that we hear that a lot more and I think that that’s becoming more accepted. It’s not like, Oh, well, this student just doesn’t want to produce what I want them to produce. Even my son—he’s nine years old—his teachers are talking about, Okay, maybe you could make a video, maybe you could do a presentation rather than a paper or something like that, just being more inclusive to people with different learning styles or different storytelling. That’s been really central to a lot of more evolving scholarship, talking about things in terms of storytelling.

Laura: Definitely, which I’m always excited by and that’s the route I’m taking for my museums and memory research paper.

Would it make sense for a student to think of a librarian as a collaborator?

Elsa: Oh, yes. I hope so! [Laughs] Yes, because that’s how I think of myself. I think about myself as playing a supporting role. I love the idea of the librarian as a collaborator, yes. What that looks like in practice is a very interesting question, it can take a lot of forms. We’re in these roles as faculty, but we can do research together.

One of the things that I’m always trying to get to the root of is, how is that being engaged with, or is it being engaged with? And what can I do to better my pedagogy and my skills to share these research methods and these research resources and how can I do that better? I’m always, in a way, collaborating with students, whether they know it or not, to see how that’s going. Whether or not it’s a measurable outcome depends on how it’s being measured, I suppose. There’s traditional metrics of, We could give a pre-test and a post-test, or I can analyze people’s bibliographies to see if they found great sources or things like that, which is not really an active collaboration.

So, I’ve done things in the past where I’ve done focus groups with students, had them come to the library, tell me about what their needs are that we’re not meeting. What are we doing well? What could be improved? And again, trying to lend the agency to the students so that they have an active hand in creating their space, their library.

I’d love to collaborate with students on their independent projects, I think that would be wonderful. But mostly from my side, I am interested in collaborating with students to create a better library for them and a better learning experience for them. But I think it could happen on both sides.

Laura: When you say create a better library… I’ll tell you the vision that is in my head and it’s narrow: I think, Oh, get different books, more books.

Elsa: Okay.

Laura: Tell me what it means to you?

Elsa: It means community. I think it means an inclusive place where people feel welcome and where they feel productive. New books are nice but it’s also about active space and active engagement. There’s a few different ways to think about it.

More books, beautiful environments. Certainly, it’s nice if the chairs are comfortable and the colors are pleasing to the eye. But yeah, obviously the resources, the best possible resources that reflect our students’ needs and their interests, really inspire them and encourage their own growth.

Sure, the best possible library would be: you walk to a shelf and the thing that you were hoping for just pops right out. But what also is even better is that that thing didn’t pop out, but you got this other idea because the thing that was shelved next to it was sort of interesting. And so you pulled that out, and then you started walking around, you know what I mean? I love the serendipitous browsing, which is why we kind of create these cataloging systems where everything’s co-located.(4) So if you’re on the right track, you’re kind of on the right track. Sometimes that’s not true. Sometimes you gotta go to a whole different floor of the library if you want painting, but now you’re interested in aesthetics where you have to go down to the basement.

But that’s just the nature of the size of the collection, which is wonderful. You want a big, rich collection with lots of different formats and things kind of jump out at you in different ways. If you have the special collections, zines or ephemera or things like that, it’s just fun to kind of go through that stuff and get ideas. And then if you’re in the stacks, you’re kind of looking through the physical spines of the books and sort of getting the smell and all the physical and psychological cues that go with just sort of roaming around the stacks and having those kinds of serendipitous experiences. That would be the perfect library, I suppose.

And then you’d have a relaxing place to be, or where you were stimulated by all the cool stuff that was going on around you, where people were discussing great ideas. And then you’d have your studio right there and you could just go in and start working. That’d be pretty nice. Coffee wouldn’t hurt! [Laughs]

Laura: As a sidebar, I recently had that serendipitous experience at the downtown Multnomah County library and it was so special. I had to work for it, had to really pay attention to my inner voice, leading me around. It was triumphant and it changed my research path.

Elsa: Wow.

Laura: I’ve had that happen a little bit at the PSU library. It’s only been open for a little while, so I’m still finding my bearings there. So as you’re describing this magical library experience, the perfect library experience, I’m thinking of the different elements: in one way, you’re describing (in my mind), like a coffee shop and sometimes there’s a lot of activity and sometimes it’s really chill, without a lot of activity. And then I’m imagining a research lab for a scientist, like things bubbling over. It’s a really dynamic space, what you just described.

Elsa: I think the best libraries are, and it fits with our mission. But I also think that part of our other mission, just as important, is to collect and preserve. I mean it’s really important that we are keeping the human record, right? And that’s what we do. I think that a lot of what we do that is important, is curating a collection that is valuable and instructive to our students and also to the community at large.

And so we need to be very intentional about how we use our resources to provide those things. Resources are limited and not just in terms of budgets, but also in terms of space and our priorities and what we can provide. And that’s where librarians come in and use their expertise to get the best, most relevant information in front of a searcher– a researcher.

Laura: What’s informing you as a librarian, right now?

Elsa: In terms of what to collect or in terms of just how I’m spending my time?

Laura: Referring to how you collect, because you were just talking about that, the intentionality of a librarian. So that leads me to wonder: well, what’s informing your intentionality?

Elsa: We need to be responsive to the needs of our departmental faculty. So, of course instructors and professors will be telling us what they need to support their curriculum.

Another good indicator for me is when new courses come up, we are asked to write a statement of support from the library, so I get to see syllabi and make sure that our collections can support the teaching and learning endeavors of the new classes that are starting. So, that’s really wonderful for me because then I can see what’s being assigned. Certainly, I’m looking at making sure that we can support the assigned reading lists, but also just kind of getting a sense of where things are going in the departments. And so that is really informative to me.

It’s also informative to me when I’m in my instruction sessions, because I have an idea of what the assignments are, the research projects, working with students, finding out what they’re interested in and then that leads me to kind of explore. And maybe we don’t have everything that they might need and that’s when I go and I find it.

I also read a lot of academic book reviews, new things coming out by certain publishers that I really value or appreciate, but I’m also still looking for things that aren’t as well represented in our collection. We need to have a sense of where the gaps in our collection are, what might be overrepresented or underrepresented. Do we need another book about Renaissance painting, or are we more interested in collecting a new exhibition catalog about yarn bombing? I don’t know. [Laughs] It doesn’t mean that the other one isn’t useful and necessary. But where do we fit in the conversation and are we representing what’s going on currently in our students’ practice mostly and what’s being taught in the curriculum.

The other consideration we have is we are part of this wonderful big consortium. We have 37 other libraries from universities and colleges in our area that also have their collections and we share that catalog. So, we call that cooperative collections development.

While I might not need to buy everything… I can’t buy everything. But the University of Washington might have one and Portland Community College might have one. Reed College might have one. Willamette University just acquired PNCA (Pacific Northwest College of Art) and now their library collection is part of our catalog. They have some really amazing parts of their collection that might not be represented in the PSU collection, but I can get it.

So those are other things that are kind of informing my collection development and what I see as a need for our library. As wonderful as it is to have all the things on the shelves in the library space, where you’re looking and searching and having those serendipitous shelf moments, there’s no way that we can have everything on the shelf right in front of you. So that can be a frustration. People like to just go and browse and that’s awesome, I get that. But there’s so much more to our collections. They’re all over the region, they’re all over the world, and they’re in the online environment. And so some of those things do get missed when you have a researcher who just really likes to browse the shelves.

Laura: I read your article, The More Things Change: The Collaborative Art Library, and I’m a huge fan of the inclusion of “collaboration” in the keyword list. But I want to back up a little bit and ask you, does PSU have an art library and actually what is an art library?

Elsa: Ah, that’s a really good question. We have our central library; we don’t have any sort of satellite library. Some departments have their own collections, but they aren’t under the purview of the library.

But an art library you are basically focused on art but it’s not to the exclusion of everything else. I’ve worked in art libraries and it’s mostly to support a specific kind of learning activity, the study of art in this case. Museum libraries are much the same, they’re there to support the research of the curators or visiting researchers who come in and would exemplify a kind of collection focus that a museum has. The Museum of Modern Craft, when it was around, had its own library and those had obviously a very specific scope and focus.

At the OCAC library, we definitely built our collection around what was being taught in school, so the different kinds of craft concentrations, but also art history. And there was a lot of social history too, you know? Libraries take many forms and many shapes and the art library is not a monolith of one kind, but you would certainly find more art books in it. [Laughs]

Laura: Thinking about the art library: so PSU’s collection isn’t considered an art library?

Elsa: Well, it would be the art section of the library. Yeah, yeah, yeah, absolutely.

Laura: Okay. Got it. Cause as I was reading the article, I was like: oh no, are we not included?

Elsa: Oh my gosh, no, no, of course not. We have wonderful, wonderful art in our library. And I mean, an art library can be conflated to mean so many things. It could be a library of art, it could be a bunch of paintings lined up. A library is terminology that can mean any kind of collection, I suppose, as long as it’s organized and preserved in some way.

We use the Library of Congress classification system so most of our art books are in the Ns and they’re sort of located in a way that’s find-able and together. But other parts of “art” are not in the Ns necessarily. They might be in more technology-related things. So like photography will be in the Ts and aesthetics and the study of beauty and things like that are going to be in the Bs, which is more in the philosophy area.

That’s what’s wonderful about the multi-disciplinary part of that, and you can look all over the collection and that can inform your art practice, certainly.

Laura: When you think about yourself as a collaborator with a student researcher, what do you make together and what do you wish you could make together? We talked about maybe a bibliography, but what are some other things? I’m trying to really wrap my head around what that collaboration is like with you as a librarian or even with the library as space?

Elsa: Well, I think that one thing that was fun that I’ve done in the past with students at the Oregon College of Art and Craft Library has been for a guest student to curate a book display which was always really fun. We have had students do that in the past where they go with the theme and find things that they’ve connected with and arrange it in a way that’s pleasing or just accessible for people.

We’ve had people do art shows in the library, certainly utilizing not only the space, but also elements of the stacks and the books themselves. One example of that is, I had a student that made all of these really delicate ceramic books and he would kind of inner-shelve them in the space and it was really neat. We had students take over the space in a lot of different ways with their physical work.

Then rearranging the library space to facilitate other kinds of making and doing and even if it’s something as simple as having a knitting circle going on in the library and we would pick topics to talk about as we were doing that, readings that we all might have done, or just sharing favorite stories or something like that. I suppose you could mean a collaboration in that way. Students collaborating with the librarian themselves or with the space or just the different ideas of use.

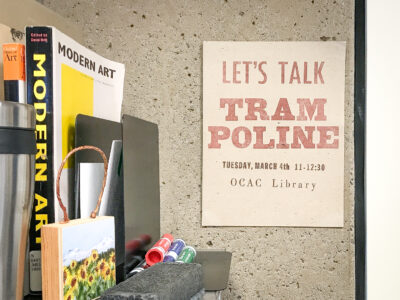

We had one student one time who was exploring repetitive practice stuff and she put a big trampoline outside the library and she would go and be on the trampoline for at least two hours a day, not jumping necessarily, but she would be sitting out there or just being in that little space. That was outside of the library and certainly everybody else was welcome to use it, [laughs] and it was just kind of this fixture. It wasn’t necessarily anything that I was doing or collaborating with myself or even the space of the library, but it did take on a form of its own because it was this sort of feature that was happening and people would talk about it and she would start to try to help generate those conversations, too, because that was part of her inquiry.

I prefer the ones where the space is being used, reused, and remixed and the collection is part of that. And anything that people are using to connect. That’s what I hope for when I collaborate with students or have them collaborate with the space or the collection.

Laura: Anything being used to connect ideas? People?

Elsa: Yeah.

Laura: What are you meaning with that connection?

Elsa: I mean specifically people. Again, having ownership of the library, having agency, and feeling like they belong there and that the library can change to support them rather than the other way around, if that makes sense. Because when you come into the library space, you have to kind of conform to it in a way, right? You need to position yourself where you need to find the things and there are rules: you have to go to the circulation desk, you have a checkout period, you have a loan period. So there’s sort of these other things. But I think that the library can also transform and be a space that can be used and enjoyed and people can connect.

A really great example of our collaboration was with that subject guide that we created.

Laura: Yes!

Elsa: That can be a work in progress and it can be molded and shaped. That kind of learning object is really wonderful because I think that it fits a need and it wasn’t a need that I knew about until you told me.

That was a great example of a collaboration. It’s a positive step that now exists and it’s something that can continue to change and be added to. There’s a lot more things like that that we can do, I think, that I’d love to see students engage with and make it their own, in a way. I can’t exactly let everybody edit that guide, but I can garner all kinds of input and feedback about it and adapt and change and be agile enough to create new things out of it.

Laura: You mentioned including things in the collection that maybe aren’t in the traditional way we think of a collection being developed. And one example that comes to mind is publications by artists. How do you see those fitting into an academic library?

Elsa: You don’t mean like a monograph, you mean like kind of ephemera or like zines or…cause that can take so many different shapes.

Laura: I think zines are a good example. I’m also thinking about small press publications, things published that aren’t easy for an institution to buy.

Elsa: Right, right. Absolutely. Well, it gets challenging. We have the usual constraints of where to get it and how to collect it comprehensively, I suppose. And so it’s helpful if you wanted to have a concentration of some kind, like artists from Portland, for example, or an artist working in a specific kind of thematic area or medium or something like that. I suppose if we were to kind of pinpoint that sort of thing then it’s a little bit more scoped rather than just like, oh, you know, kind of anything we come across, we get.

Our special collection is a good place for some of this stuff, especially when the formats are a little unstable. Case in point, with a zine, I couldn’t really throw that on the shelf, it would get kind of destroyed, right? There needs to be a special place. And digitization of that kind of thing. Then that can go in our institutional repository, like PDXScholar, if it was somebody from our community, that would make a lot of sense. So there’s room for that and it tends to be kind of in what we think of as our special collections. Just for its own kind of protection, just physically, so it doesn’t fall apart.

Some libraries have very specific collections based on that. You know, ephemera collections, and postcard collections, for goodness sake! The New York Public Library has an amazing historical menus collection and things like that, it’s wonderful. It goes library by library and a lot of that has to do with the institution that it’s supporting.

Laura: I saw there was a faculty announcement that you are an associate professor.

Elsa: Oh no, I’m an assistant professor assistant. I haven’t gotten tenure yet.

Laura: Sorry, I mix them up. Do you teach classes?

Elsa: Librarians have faculty status at Portland State, or they can. We have faculty status and so we do teach, but teaching is defined as provision of library services. So our kind of pedagogy is providing information. We do teach, I teach instruction sessions. It’s kind of defined as, provision of library services is what teaching is, which means that we are providing the ability to do the research; that is our process.

Well, how is this going to look? What is the theme of this journal?

Laura: There is no theme for this issue. I bring the theme. For me, my practice is about books, collections of knowledge, selecting pieces of knowledge, libraries as spaces, people as collaborators. When we talked in August, I was like: oh, Elsa is a great resource. I need to understand more about what you do.

There’s a woman in Montana who does a traveling bookstore. And she goes all over the country and she comes to Portland. So I’m thinking about interviewing her in the winter. Kind of along this theme of books as spreaders of knowledge and trying to figure out where do I fit? Why is that a part of my practice? So, that’s why I’m talking with you. I’m like, why am I so drawn to the library, books, and collecting?

Elsa: I love that idea of the traveling bookseller, that’s really neat.

I had a colleague at OCAC, she’s at Reed now, she’s a book artist, Barbara Tetenbaum. And she was doing this really cool project where it was called The Slow Read and she was using Willa Cather’s book My Ántonia and she had these display monitors up in various places, and in different cities, too.

It would be just a display of one page of the book. And so people could kind of come and read that page. And then the next day there would be a new page. The idea was sort of like this community read, but also really slowly.

Laura: At the library?

Elsa: We had one of the monitors up at the library. But she went out all over the place and it was centered in Nebraska, because that’s where the author was from.

Laura: And she’s at Reed College now?

Elsa: Yeah. She and I used to teach together and she’s wonderful.

Laura: I’m looking at the website right now.

Elsa: Oh yeah, you got it? Okay, great. That puts me in mind of what you’re talking about, right?

Laura: Yes!

Elsa: Yeah. Pretty neat, huh?

Laura: Oh, my goodness. Where did you teach with her?

Elsa: At OCAC. She was the chair of the Book Arts department. Yeah, and then she and I co-taught a student success class for incoming freshmen. It was basically like a college skills class. I think we called it College Skills or something like that. But it was me teaching research and then also just how to be a student and how to succeed in school and even like financial literacy and stuff like that.

So she and I became good friends because we designed the whole course together and she was in the middle of this whole project in the last year that I was there and I was so blown away. You know, talk about collaborative and text as experience, right?

Laura: Oh my gosh. Text as experience. Did you just make that up?

Elsa: I just made that up and I don’t know, [laughs] maybe it flew in from somewhere. She’s one of those people that’s really quite amazing.

Laura: I’m going to have to spend some time with this. See, I already benefited from talking with you! I would not have known, oh my gosh!

This issue of SOFA Journal won’t come out until mid December, I think. And I will keep you in the loop. And just so you know, I personally publish it as a printed zine. And lucky you, you’ll be a lifetime subscriber. So you’ll get a copy of every one that I do in the next year and a half. And then I’ll also send you the back issues.

Elsa: Well, they’re beautiful. I’ve been looking at them on PDXScholar. I’ve never seen a physical one, but I’ve been enjoying looking at them, they’re so rich and pictorial.

Laura: Awesome. Thank you so much for your time.

Elsa: Have a wonderful weekend!

Laura: Thank you! Bye!

Footnotes:

(1) Oregon College of Art and Craft was a private art college in Portland, Oregon, from 1907 until 2019 when it terminated all of its degree programs.

(2) A learning object is a digital, open educational resource that is created to assist in a learning event. M, Vanessa, and Jane C. “What Are Learning Objects?” Instructional Resources, October 15, 2021. https://blog.citl.mun.ca/instructionalresources/what-are-learning-objects/.

(3) From Elsa: “I was specifically talking about the Library Guides and from our website, Subject, Course, and How to Guides, which are created by Portland State librarians to help you! These guides provide helpful resources, strategies for research, and tutorials.”

(4) Co-located means having multiple things located together—like the sections in a library—the painting books are near the other painting books, Portuguese language books are next to the other Portuguese language books, and so on. Definition provided by Elsa Loftis.

Laura Glazer (she/her) is a student in the Art and Social Practice MFA program at Portland State University. She graduated from Rochester Institute of Technology with a BFA degree in photography and lives in Portland, Oregon. Her curiosity about people and the visible world guide her as she uses research, conversations, and collaboration to create projects. She processes and organizes research through publications and local, free distribution methods of printed matter and visual culture such as brochures, flyers, and postcards. See her projects and process notes on lauraglazer.com and Instagram.

Elsa Loftis (she/her) joined the Portland State University library faculty in 2018 as the Humanities and Acquisitions Librarian. She is the subject liaison to the College of Art + Design, and the Film Studies, World Languages, and Literature departments. Prior to her arrival at PSU, she was the Director of Library Services for the Oregon College of Art and Craft, worked as the librarian for Everest College, held positions at the Brooklyn Public Library, the Brooklyn Museum Library and Archives, and the Pratt Institute Library. She received her MLIS from the Pratt Institute, and her BA in International Studies at the University of Oregon.