Fall 2022

Cover

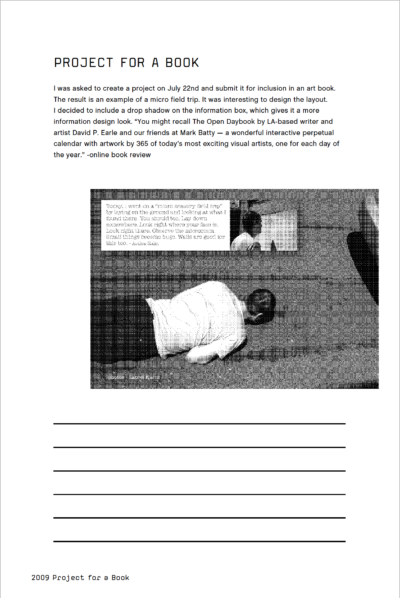

“When The River Becomes A Cloud” launched on June 9, 2022 after a 6-month exploratory pilot period of collaboration with teachers, staff and students at Prescott School, and evolved into a multi-year, collaborative public artwork throughout the campus. Prescott School is a Pre-K-12 public school in rural Eastern Washington. While developing the work, Amanda Leigh Evans and Tia Kramer – both program alumni who are interviewed in this issue – have been long-term artists-in-residence at the school.

In the program trip during 2021-2022, we visited Prescott Elementary School and participated in exercises with Amanda and Tia, and the students, faculty, and staff at the school. We sought to complete a participatory course on the campus: each MFA candidate was paired with an elementary school student and created unique choreography that happened consecutively throughout the playground and landscape around the school. We also enjoyed in-depth conversations with Tia and Amanda about the inception of their collaboration, the value of sharing language from the program, and the beautiful endurance required for public art projects.

It’s thrilling to see the project evolve and learn that “When The River Becomes A Cloud” will result in large, permanent public artwork. A continuum for those who came before and will come after.

Reading this issue of the SoFA Journal is especially enjoyable because we get to have a window into names and projects connected to the program. We see how they came together, where they lead, and what social practice artists do after their time at PSU.

We selected this image for its impressive birds’ eye view of the project, and because of the sweet memory of the school last spring. Someone threw a snowball in their choreography. There was clapping and stomping at the start. Hopscotch. The exercises inspired us beyond the visit to dream up performance scores, make more art with children, and collaborate with one another in big and small ways in our own practices.

Sincerely,

Gilian Rappaport and Luz Blumenfeld

Letter from the Editor

What is Social Practice?

When you tell people you are getting an MFA in Social Practice, they always have follow up questions. Often no matter the definition you give, your conversation partner will say something like, “So you make murals?” or “Like art therapy?” Nothing against murals or art therapy, but no, that is not exactly what we are doing here. What we are doing is varied and vast and has been going on for a while. The A+SP program at Portland State University started in 2007 and around 70 artists have graduated since then. For this edition of SoFA, each current student in the program was asked to interview a program alumnus. Through the interviews, we see glimpses of how the program changed and grew based on who was taking part and how social practice has changed and grown as a field.

I wanted to take this opportunity to crowdsource. Who better to sympathize about the challenge of defining social practice than our predecessors? How do the many alumni of our program describe the field in which we work and play and dig and live? I looked to the Terms and Topics formulated by program founder Harrell Fletcher and imposed a small self-initiated artist residency within the interviews of my colleagues. I asked them each to add the question, “How do you describe social practice to non-artists?” to their interview. Some chose to include the question in the published version of the interviews you are about to read, and others did not, but the responses they shared with me began to paint a picture of the expansive field of social practice and reminded me why I found it captivating to begin with.

Avalon Kalin, alumnus of the program’s first graduating class, told Becca Kauffman that social practice is “a tendency in art.” He also introduces a game that he and Becca play in their interview, and you can play it too. Constance Hockaday told Gilian Rappaport, “I like to take risks in public with people. I like to make magical things happen— unexpected happenings… It’s about getting the audience to take the risk with you.” Salty Xi Jie Ng claims, “The work makes you as much as you make the work.” Salty’s work feels intimate and humorous and her conversation with Nadine Hanson feels the same.

As Mark Menjivar puts it, “Some people self-identify as social practice artists, other people don’t.” Not everyone uses the term social practice. Some find it easier for themselves and their potential participants or collaborators to relate to other terms like social sculpture, social art, and socially engaged art.

Tia Kramer calls herself a social choreographer and uses the term socially engaged art because it “makes more sense in the rural context.” She shares in her interview with Marissa Perez that working with a small town community has meant explaining less often what she does, because the people around her have already been a part of it.

Overall, there is a sense that, while pinning down social practice can be difficult, it allows immense freedom in terms of how it is practiced, where it happens, and how it can serve the artist and others. You will probably notice that when many of the artists interviewed talked about how they share the idea of social practice with others, they talk about starting a longer conversation; they describe what sounds like the beginning of a relationship being formed, a collaborator being recruited, a social practice project being born.

– Caryn Aasness

A Sense of Unexpectedness

“Some of those relationships become really close friends and other times it’s like a person I just bump into at the coffee shop, and they’re like, “Thank you for that weird thing you did.’”

Tia Kramer

Tia Kramer is a social choreographer and social practice artist. She is embedded deeply in Walla Walla, Washington and her work taps into many different parts of her experience and community. I’m interested in the ways that people use their practices to explore the places that they live and to ground themselves in the people around them. I was drawn to Tia’s recent series of “performances for one.” In one called, What You Touch You Cannot See, she choreographed a performance for her mail carrier, Phil, where each person on the mail route sent Phil a package filled with stories, drawings, plants, and poems about the things he had delivered for them. In another she created a walk home filled with synchronicity, messages written on sandwich boards, and a parking lot light performance for her friend Guillermo. Tia is so skilled at creating projects that reveal and strengthen the ways we are connected. It was such a pleasure to hear about Tia’s experience working with the different layers of her community.

Marissa Perez: Let’s start with: how do you define social practice? And specifically, how do you define it for anyone who’s not familiar with the term? I’m also curious if you still call what you do social practice?

Tia Kramer: Yeah, that’s a good question. One of the things that’s been interesting about being in a small community is that when I was in the program, that question felt really important because it is a question I was asked all the time: What is social practice? And how do you define it? But now, six years into my life as an artist making public socially engaged art here, people know me and my work in the community–non artists know me and my work–and so I don’t feel like I have to define social practice very often. They just know, “oh, that’s Tia’s practice.” And now that fellow PSU graduate Amanda Leigh Evans is here they might say to Amanda, “Oh, I think I know a bit about what you do.” I don’t end up defining it a lot. And simultaneously, Amanda and I are often working on defining it together.

In recent years, when people I don’t know ask about my practice I begin by saying that I’m a social choreographer. I’ll say, “I’m a socially engaged artist, which is a little different than what you might expect an artist to be. I don’t necessarily do painting, but instead what I’m interested in is the interactions between people and creating creative experiences for groups of people that shift who is the artist and who has agency and who has power.” Then I’ll say, “Specifically, I am a social choreographer. I have a background in performance and I think a lot about choreography— creating movement for and of people. I choreograph experiences for a group of people that change their perception of each other and their everyday life.”

I also use the term “socially engaged art” more than “social practice,” because that makes more sense in the rural context.

Marissa: Yeah, and it feels like it makes it an active term so then it can click for people a little more.

Tia: And socially engaged art has the word art in the definition, which is helpful. It says I’m inherently working with people in my creative projects. That’s enough for me to then follow with: “for example, as a social choreographer, I created this performance for one person, for my mailman and this is what it looked like…” Or, “I’m an Artist in Residence at Prescott School and instead of teaching art to kids, Amanda and I are collaboratively making art with kids so that their voices have agency. We don’t know what the outcome is going to be.” There’s a sense of unexpectedness, in all the things that happen within our practice, but we’re really facilitating that experience.

Walla Walla, WA. Courtesy of Tia Kramer

Marissa: I’m curious about your process of feeling rooted in Walla Walla and how it has affected your practice? How has your practice also affected the ways you are rooted in place?

Tia: I really love this specific question, because I think that both of those things are deeply true in a smaller place. I’ve lived in Seattle, and I moved to Walla Walla in 2016. My current collaborator, Amanda, moved from Portland. I went through the program in a small town and I’ve mainly been doing socially engaged art in a small place. That isn’t true for Amanda and she is constantly surprised at how different social practice is, and the ramifications and the implications of the work are in a small place. In some ways it is a different practice. In a city, you can go put signs up around your neighborhood as an anonymous person. But in a small place, if you put signs up around your neighborhood, most likely people will learn that it’s you that did it and then they’re going to ask you about it. And if they don’t know it’s you, they might think, “Oh, it’s part of a class or a project or an initiative.” So the implications of these actions become different–anonymity isn’t present or possible in the same ways. Because of that, there are positives and negatives that come with those implications. The positive is that there’s potential for deeper work and for complex layers of participation.

When I lived in Seattle, and in urban places, I wanted to create experiences that were slow and intimate. And then I moved to Walla Walla. Here EVERYTHING can feel slow and intimate. I think I realized that, in order for a practice to be meaningful to me here, it has to get more specific and less generalized. I would also say that, now that I’ve been working here for six years, all of my relationships are deeply intertwined with the work I do. Even the relationships I have as a parent– the kids in my life know the projects I’m doing, or they encounter me doing my work in the world, and so do their parents. So there’s a really inherent interconnectivity between my social practice work, my community, and the community at large.

I also know so many people from my work! For example, the performance I made for my mailman was created with 87 people on his mail route, which means that’s 87 more people that I have relationships with in a tiny town where you bump into people all the time. And that’s just the relationships developed in one project. Because of that, there are things in my practice that I don’t do as much anymore. Now I am more hesitant to build really deep, intimate relationships, because I’ve done that with so many people, and now I have a lot of social obligations.

Marissa: Are there ways that you felt that you needed to be rooted before certain projects were possible?

Tia: I strongly believe that social practice artists should be really careful to consider the “service” or “do-gooder” components to their work, both intended and unintended. I feel strongly about that. The choices that we make as social practice artists have implications on people and those implications need to be considered. For that reason, I feel a really strong obligation to do antiracist training and to work on myself as a white person collaborating with POC artists and communities, and I need to deeply understand what that means in a small town context. For example, I really emphasize building trust, and ethically following through on projects. I did a theater piece where I constructed a theater performance based on the stories of immigrants in the community. And the people who were in that project with me saw how carefully I considered every step, like getting their feedback on the script and asking for their input on the performance. And when we invited their families we wanted it to be fully accessible, so we paid for their tickets and provided childcare and simultaneous interpretation. That level of consideration has had unexpectedly long term consequences. Now when I ask them, “Can I meet with you to have coffee to talk about a new project I’m thinking about?” they are often curious and say yes, because we feel a mutual respect and connection to each other. That makes my work possible. But sometimes that is also a burden. It’s a lot of work to hold those relationships. It is emotional labor.

When I look at the work Amanda and I are doing together as Artists in Residence at Prescott School [a preK-12 public school in rural Eastern Washington], I think that the work that I’ve done in the community to build trust has paved a way for us and for her, as a newcomer, to just dive right into a project. There’s levels of trust that have to happen and that trust takes time to build.

Marissa: Yeah. It’s a complex answer and also very simple. I’m wondering about how you use relationships in your work. I’m curious about how you’re being strategic with your relationships.

Tia: I would push back against the word strategic, although I think that that makes sense. But it just has a slightly extractive quality to it. I do think there is strategy, so I’m not ignoring the fact that I’m being strategic— but I would say that I’m consciously working to build relationships that are outside of my inner circle. I know what my family knows and what I have been exposed to in the world, and I see how communities, even in a small town, get super isolated. I’m interested in how we disrupt that isolation. How could I meet someone that I wouldn’t have met or learn something new that I haven’t learned? And some of those relationships become really close friends and other times those relationships are with people I just bump into at the coffee shop, who might say, “thank you for that weird thing you did.”

Marissa: I get that. It does feel bad to hear the word strategic in these contexts because it feels related to networking. Whereas I feel like what you’re doing is more careful than that, like you’re being careful because you’re trying to create care.

Tia: I might even separate careful into two words: “care” and “full.” Much of my work is based on the feminist ethics of care, and now, because I have worked with feminist care ethics for a long time, I also find myself pushing back against those philosophies. I find myself resisting projects that require too much care. I just want to make.

Marissa: That brings me to my next question. It seems like the project with Amanda at Prescott School is not necessarily super different from your other work, but might be part of a departure from your more one-on-one intense relationship-building practices. How are you feeling about this project? And where is it fitting into your practice?

Walla Walla, WA. Courtesy of Tia Kramer

Tia: What I would say about the work with the When The River Becomes a Cloud project, is that the work is merging together all of these different aspects of myself. I have a seven year old and a three year old and I have been making art with them since they were little. Through the pandemic, we made an imaginary zoo that had hundreds of imaginary animals that you could visit in the park. I have so many practices around my work with kids that I haven’t formalized yet, and this project formalizes many of them in a very concrete way. I think that the project launch was about helping the students see the dissolving of the boundary between life and art, or between performance and life. We were very intentional and this is where I get into strategy. The students at Prescott School had not had an art teacher at their school for eight years. It’s a pre-K through 12 school, so they haven’t had any exposure besides what their teachers show them. So of course, the very first thing students think is: “Oh, you’re a public, professional artist. That must mean you’re going to make a mural with us.” From the very beginning, we wanted to challenge and expand their notions of what art practice can look like. We wanted to crack open art, and that’s what social practice does, and that’s what performance can do. It can really shift us to ask, “Are we performing? Are we part of this project or is it for us? Who is the audience?” Unlike with a performance for one person as the audience and a huge team of performers, this initial project with the 330 students at the school was a project in which every person was both in it, part of it, and also the audience for it. We created an immersive experience that’s very unusual in a rural context. In fact, I would go so far as to say it was radical for these kids.

Marissa: So in your performances for an audience of one, you create an immersive experience for one person. I’m curious about how the experience of creating this performance affects the performers and their relationships with each other and the audience members?

Tia: To describe this let me step back, a typical format for theater might be a solo performance, one person performing for a big group. My performance for an audience of one flipped that form. I created a performance in which a big group of people performed for one person. Conceptually that is very concise. Everyone who’s invited to participate understands the shift in framework. They find unexpectedness in the form which often inspires their participation. Participants really go all in in a way that’s beautiful to witness and experience. The form ignites the imagination. Very early on participants can understand that as they’re engaging in the process they are getting something out of the performance, which is really different than if you’re performing for a big group. If you’re performing for a big group, you immediately can imagine the audience and you almost disassociate, like, “Okay, this part of myself is behind, and I’m going to just place it this way.” But if it’s for one person, you know how to create a one on one interaction and you know that your experience of what you present to someone is going to change that person, and they are going to change you, because that is an experience we all have on a daily basis. So what I found to be really beautiful is that what I’m often using for these “performances for one” are pre-existing relationships that I’m taking out of one context and putting into another.

I think that in the example of the performance for Guillermo, he knew all the people that were performing except for a team of musicians and some dancers. And now, two years later, when he bumps into those people he didn’t know, he finds it to be really awkward because he knows nothing about them but knows the other participant might know a lot about him. But, all of the people who participated who had pre-existing relationships with him, those just got even deeper after the performance. However, it was different for Phil, the mail carrier, because in that performance, What You Touch You Cannot See, some of the people who participated were friends, but many of the people he didn’t know. But he knew a lot about them through their mail. Their participation created a new bridge. Once he opened the package that they gave him and the insight they gave him into their life, when he bumped into them on the route, he’d be like, “thank you for that thing you did for me.” And then they would respond, sharing about this new knowledge and experience they share in common. That’s a new starting place for a friendship or a relationship. So I think there’s a lot of relationships that he has that are dramatically different now. And he’s gonna probably be on that mail route for the next 20 years. So it’s also interesting to see how those relationships are changing.

Walla Walla, WA. Courtesy of Tia Kramer

Marissa: My dad was a mail carrier for 30 years, and he was a rural mail carrier. And just reading about the project, it felt special to me. And it does feel like such a ripe place for socially engaged work, because it’s a place where there’s so much social engagement and you can’t see it. It’s like my dad, if he’s talking about a customer, my mom will be like, “and what’s their address?” And he can recite their address right here. He’s got them stuck in his brain. You know, all the exchange of information is there, just without the personal connection and you just made a spark to be like, “Look, it’s just one little thing that it takes.” And that’s really special.

Tia: Yeah, it’s interesting, because Phil will say, like, “Hey, Tia, do you know, Bob? 1826 Newell!” And I’m like, “Oh, yeah, I know, Bob!” He can recite 400 addresses by heart, which is really amazing.

Marissa Perez (she/her) grew up in Portland, Oregon. She is a printmaker, party host, babysitter and youth worker. She’s interested in neighborhoods and the layers of relationships that can be hard to see. Her dad was a mail carrier for 30 years and her mom is a pharmacist.

Tia Kramer (she/her) is a social choreographer, performer, artist, and educator interested in everyday gestures of human connection. She creates experiences that interrupt the ordinary, engaging participants in embodied poetry and collective imagination. Tia holds an MFA in Art + Social Practice from Portland State University and a Post Bacc in Fiber + Material Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Currently, Tia is developing When The River Becomes a Cloud (2022-2024), a collaborative public artwork as part of her long-term Artist-in-Residence at Prescott School (PreK-12) with Amanda Leigh Evans as part of Carnegie Picture Lab’s Rural Art Initiative.

A Closeness To Life

“I think and I propose that collaborative art spaces are semi-fictional worlds because we are birthing into being a kind of relational experience that did not exist before.”

Salty Xi Jie Ng

I was introduced to Salty Xi Jie Ng’s work through my twin brother, Nolan, whose time in the Art & Social Practice program overlapped with Salty’s. I was, and remain, so drawn to the intricate yet inconceivably vast spiritual landscapes that are created and explored in her interdisciplinary practice. In my own work, I’m feeling curious about fantasy as a tool and site of social engagement and performances of the everyday, themes which I see represented in Salty’s projects. We met for the first time via phone; Salty, in Singapore, and me, in my apartment in The Bronx. She was patient and warm as I asked her some questions about her life and art practice, and she shared some of her cosmic wisdom.

Nadine Hanson: Do you have a morning routine?

Salty Xi Jie Ng: I love that question. I think about my morning routine all the time. How can I actually do it better? I wake up and I make my bed, and then I have a customized stretching sequence that I made for myself and what my body needs, although it probably needs updating, and it ends with some qigong and brushing of excess energy from the body and petting the body to awaken it. After that, I will take a quick shower, because it’s hot in the tropics so a shower is necessary every morning and refreshing because it’s very hard for me to get out of the hypnagogic sleep state. After that, I’ll make breakfast which is usually fruit, oats and an egg. So that’s the morning routine.

Nadine: Where do you feel the most calm?

Salty: When I’m with a bodyworker or therapist I trust, or in the arms of my partner when we cuddle, or a moment of meditation where I reach a sense of spaciousness.

Image courtesy of Salty Xie Jie Ng

Nadine: What is your favorite piece of clothing?

Salty: There are too many pieces of clothing that I feel attached to. When sorting through my life’s possessions recently, I found about 50 pairs of old, saggy, crunchy underwear I’d kept since teenagehood. I kept some to make a shawl of my teenage girlhood.

Nadine: Do you identify as a social practice artist?

Salty: I identify as an artist who makes a whole spectrum of work, including social practice, performance, film, installation, writing, movement, and so on. I think it’s important to be as expansive as one can be because there’s many ways to express oneself for different seasons of our lives. Working relationally is just one approach or one tool that I might have, one response to a context. I’m at a time where I really want to allow myself to be, and be seen as a whole spectrum of things.

Nadine: How do you explain social practice to non artists?

Salty: Art that is made in collaboration with other people, that is not focused on making objects, where the shared experience is the art itself. I think the ways that shared spaces in socially engaged art projects unfold can be very mysterious and alchemical, even if there’s a methodology and a lesson plan. I think about how all the energies of people and their histories intersect, and how we change each other through the ways that we spend time together in those spaces—there’s something very cosmic about that. The work makes you as much as you make the work.

Nadine: Could you tell me a little bit about what draws you to making work on the subject of intimacy?

Salty: In my life, outside of artistic practice, I’ve always been drawn to intimacy: I’ve always wanted to come closer to life in any way that I could, to the sense of being alive and uncovering things. I remember feeling that from the time when I was a child. Now, I think of much of my work as creating spaces for intimacy. In The Grandma Reporter issues 2 and 3, I investigated the subject of intimacy with senior women in Portland and Singapore. Now I’m thinking a lot about eroticism—also a closeness to life, a sister to intimacy which vibrates at another tone.

Image courtesy of Salty Xie Jie Ng

Nadine: In your project “Not Grey: Intimacy, Ageing, & Being,” Zubee Ali describes her first love affair with a woman and says: “she introduced me to love– being able to love another and allowing myself to be loved.” In your experience, how can one allow oneself to be loved?

Salty: By first learning to love oneself and then saying to the universe, let me be loved– by the sun, the sky, the moon, the wind, the waters, and then, maybe, by someone. But know it will most likely bring a good amount of pain! You must be ready. Often you have no choice; it will come even when you are not ready.

Nadine: Have you ever been in love?

Salty: Oh many times. Always, forever.

Nadine: Do you think that part of love is fantasy?

Salty: Part of it, yes. I think that when we start loving something, there’s always a sense of projection– a sheath of fantasy– around it, whether that thing is a person, a subject, a theme, an animal, an idea. I’m very interested in that sheath of fantasy, in the space of the semi-fictional. As you love something longer, you come, perhaps, to painful truths about that thing, which are necessary to experience.

Nadine: Could you articulate how you interact with fantasy?

Salty: I think and I propose that collaborative art spaces are semi-fictional worlds because we are birthing into being a kind of relational experience that did not exist before. Just by sharing space in the ways we do, we are making a future we want to see and be in. In that space of semi-fiction, new ways of being and being together land softly; new visions of life coalesce like rain clouds, new truths emerge. Fiction and reality cannot do that alone.

Nadine: What has performance allowed you to do in your work?

Salty: Performance takes me to an altered and heightened state of being, where I think performers channel and access different energies.

made on residency at Arteles Creative Center, Finland, 2014

Image courtesy of Salty Xie Jie Ng

Nadine: What do you think those energies are?

Salty: [laughs] What a metaphysical question. Energies from other realms and dimensions, energies from nonlinear time and space. Whether consciously or unconsciously, performers access myths, messages from other entities, histories of a place, and more. An entire field is speaking to them.

Nadine: What have you been up to since you’ve graduated?

Salty: I made The Inside Show in collaboration with inmates at Columbia River Correctional Institution. I got a job as artist-in-residence in 2019 and 2020 at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, where I made Words of Support, Faculty Relations, A Whaling Descendant Performs In Four Acts, and The Alternative Moby-Dick Marathon. When the pandemic hit, I came back to Singapore and really struggled with mental health. For five months as the artist-in-residence of a Singaporean mall, I ran Buangkok Mall Life Club, a retail unit turned art space. Then, among other projects, I worked on Not Grey: Intimacy, Ageing, and Being, STREET FOUND, and Dear Singapore Art Museum Acquisition Committee, from which emerged my curator persona Sheralynne Dollatella-Wong Jia (MA Curation, MA Arts Business). She challenges museum practices, specifically around acquisition. It was a response to being part of the international contemporary art world while feeling disturbed by the way it operates. Recently, Sheralynne worked with the Museum Why network in Scandinavia for their symposium rethinking museums.

Somewhere in there, my paternal grandma, whom I’m very close to, passed away. Soon after, I began a residency at the Singapore Art Museum. I spent my time there processing the early stages of grief, from which emerged Baibai Research Group, a growing body of work on expanded spiritual expressions stemming from Chinese ancestor worship, the spiritual lineage I carry. There is learning about syncretic Chinese religious practices in Singapore, grieving in public, working with non-human collaborators, and being able to connect with people around my generation in Singapore on a subject we don’t quite engage with together. It’s a beautiful opportunity to re-imagine the ritual practices I grew up with.

Singapore Art Museum / Singapore Art Week, 2021-22

Image courtesy of Salty Xie Jie Ng

That was a lot! Currently, I’m taking a pause to re-envision my practice. My friends could not believe that I would have no projects lined up, because I’ve been going nonstop for so many years but I think that recalibrating is so important. Life can be so many ways. I’ve been on a quest to sort through my entire life’s possessions. Given I’m a hoarder, this has been a mammoth task. I’m determined to finish because I think it will create the space to re-envision and make space for new things to enter my life. It’s already happening.

Pausing on big projects has also been about detangling my sense of self-worth from the work I have lined up, or lack thereof. People don’t talk much about the toxic culture of production and competition perpetuated by hegemonic art world forces. I want to live in a world where artists’ creative gifts can be honored and met by the world in healthy, sustainable ways.

Nadine: Ritual has come up in your work, and in an interview about your recent project, “Baibai Research Group,” you talk about “ritual as wish fulfillment.” Would you be able to share some wishes that you’ve fulfilled (or hope to fulfill) through ritual?

Salty: My paternal grandmother’s safe passage to the next realm, which can be prayed for through certain prescribed rituals, or rituals one can invent. The ability to communicate with departed loved ones just by being in a space of ritual. Contributing towards them having an ample and interesting afterlife— in Chinese ancestor worship, paper effigies are burnt to send gifts to the other realm; for example, a dog to annoy my paternal grandma since she hates dogs, and a vespa and cigarettes for my paternal grandfather. The releasing of old traumas or stuck feelings, while meeting selves or a renewed self that can come through performance— ritual is performance.

Nadine: Do you have any advice for how to care for oneself while making socially engaged work?

Salty: Here are some thoughts, and I’m telling this to myself as much as sharing with you. Establish healthy boundaries around communication via text and email. Take at least one day off a week where you don’t work or think about it (try!). Be able to envision, as much as possible, the many kinds of labor involved so you can pay yourself appropriately, or expand the team and learn to share, outsource, delegate, trust. I am a big empath and easily affected by the energies of others. By the end of the day, I always shower, stretch and do some qigong exercises to release excess energy. Spending time alone is really important. Part of that time can be spent reflecting on what part of the work brings you joy and curiosity, and how to keep connecting with that while a project unfolds.

Salty Xi Jie Ng (she/her) co-creates semi-fictional paradigms for the real and imagined lives of humans within the poetics of the interdimensional intimate vernacular. Often playing with relational possibilities, her transdisciplinary work is manifested from fantasy scores for the present and future that propose a collective re-imagining through humour, care, subversion, play, discomfort, a celebration of the eccentric, and a commitment to the deeply personal. Her practice dances across forms such as brief encounter, collaborative space, variety show, poem, conversation, meal, publication, film, performance.

Nadine Hanson (she/her) is an artist based in New York City who, for the last decade, has worked service-industry positions in bars, restaurants, hotels, and other people’s homes. Her occupational experience informs her interdisciplinary practice, which uses collaborative approaches to performance, writing, and experimental documentary to explore commonly under-valued and feminized knowledge bases and forms of labor.

The Intersection of Process and Material Outcome in Socially Engaged Work

“I want exchange and interaction and I think involving people’s physicality instead of just the way they think creates interesting conversations. There’s a pleasure and engagement piece in it for myself as an artist.”

ZEPH FISHLYN

Before coming to PSU’s Art + Social Practice program, my practice revolved mostly around material objects; I took photos, I painted, I made collages. While I greatly enjoy (and still do) these things, I wanted more from my art practice. I wanted collaboration and conversation, public interaction and personal storytelling. I wanted social practice before I knew what to call it. But sometimes I struggle to figure out where my past interest in material forms fit into my socially engaged present. I still want to make things, but I want to do it with other people rather than alone. How do I create objects in a socially engaged way? What do I do with the subsequent objects? What physical matter comes out of conceptual projects? I hoped to answer some of these questions with Zeph, whose range of work often contains physical materials and objects in some way or another.

Portland, OR. Photograph courtesy of Zeph Fishlyn.

Photograph courtesy of Zeph Fishlyn.

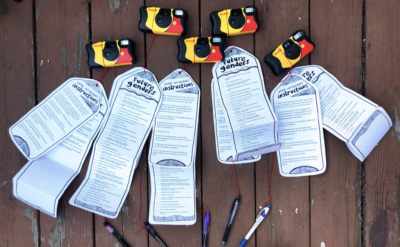

Olivia DelGandio: I want to start by talking about Glimpses of Future Genders and Sum of its Parts. Could you tell me about the ideation process for these projects?

Zeph Fishlyn: Those projects were very experimental in terms of format and engagement and were much more focused on process rather than product. The first version I did was at San Francisco Pride and it felt like a fun experiment to do in a setting where people were already pretty willing to participate in things. So I sent a few disposable cameras off into the crowd with a set of instructions and was super curious about what I might get back. I also really wanted it to be a physical experience where people had to hand something off to one another and then physically mail it back to me using a pre-addressed envelope. It was like an old school, pre-social media experience.

Olivia: That sounds like such a fun experiment. I’m thinking about how you had no idea what you were going to get back. How did you let go of expectations for a certain outcome since you couldn’t control it in the slightest?

Zeph: Well, the first time I did it I was kind of just like “this seems fun” and wasn’t super concerned with the outcome. Of course, I wanted the cameras to come back to me but I was more intrigued by the possibilities that a project like this could hold. I even found some joy in accepting that maybe nothing at all would come of this project.

Olivia: Socially engaged work is so centered on process, this work really exemplifies that. It’s less centered on material outcomes but you did have a collection of physical photos at the end of these projects. What did you do with those?

Zeph: I have them documented on my website but I never really did anything more with them.

Olivia: I think that’s something I struggle with as a social practice artist. I’m always wondering what to do with the results or physical manifestations of a project. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Zeph: In an ideal world, I’d like to have both a project focused on process and also an interesting material outcome. I think it’s especially important to have something physical to share with those who couldn’t engage in the original project.

Olivia: Me too. In looking through your website, I noticed a lot of your projects have a material component to them. Could you talk about the importance of material making in your work?

Zeph: I really enjoy the experience of having something tactile in my hands and the exchange of materials from person to person. I come from a background of visual art so I was definitely more object oriented before coming into the program but I was never interested in things that just sit on a wall as decoration. I want exchange and interaction and I think involving people’s physicality instead of just the way they think creates interesting conversations. There’s a pleasure and engagement piece for myself as an artist.

Olivia: That’s really interesting. I also want to talk about Those We Glimpse. I’m really interested in doing a project focused on queer storytelling and want to know more about your experience with this project. Did you personally talk to everyone who had a story to share and record the stories yourself?

Zeph: No, I worked through a series of installations. The first installation was made of queer stories from my own family and I asked people to write in stories from their own family that alluded to some history of queerness. Then they hung those stories on the installation and the new stories became the core for the next installation where I invited people to come, read these stories, and contribute their own.

Olivia: Did you have a favorite story from that project?

Zeph: There’s one I love about two aunts dying in bed together and it was so simple but it had me picturing whole lives for these women. It really made me think about the power of imagination.

Olivia DelGandio (they/she) is a storyteller who asks intimate questions and normalizes answers in the form of ongoing conversations. They explore grief, memory, and human connection and look for ways of memorializing moments and relationships. Through their work, they hope to make the world a more tender place and aim to do so by creating books, videos, and textiles that capture personal narratives in a caring manner. Essential to Olivia’s practice is research and their current research interests include untold queer histories, family lineage, and the intersection between fashion and identity.

Zeph Fishlyn (they/them) is a Canadian-born, SF Bay Area-based interdisciplinary artist, educator, and cultural organizer. Zeph’s participatory projects, drawings, objects and interventions cultivate social and ideological mutations in urgent times. Zeph is a serial collaborator with groups taking creative action on economic and racial justice, climate change and LGBTQ liberation— including the End of Isolation Tour, Beehive Design Collective, Greenpeace,the San Francisco Anti-Displacement Coalition, the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, Heart of the City Collective, the PDX Trans Housing Coalition, and the Center for Artistic Activism. They played key roles in creating and maintaining collective spaces for artists and activists, including Lobot Gallery, a live/work/event space, and the 2027 Mutual Aid Society, a resident-run affordable housing co-op.

Small Things Become Huge

“Making sense of something, making it clear, and re-presenting it, that makes the whole world like a library. And makes you the curator of that library as an artist to just bring to people.”

Avalon Kalin

Avalon Kalin is an everyday artist. He makes small works about little things, big works about small things, and smaller works about bigger things. No matter the size of the work or the subject matter, the scale of his appreciation for the delights of this world is consistently enormous. He is seeking the sublime.

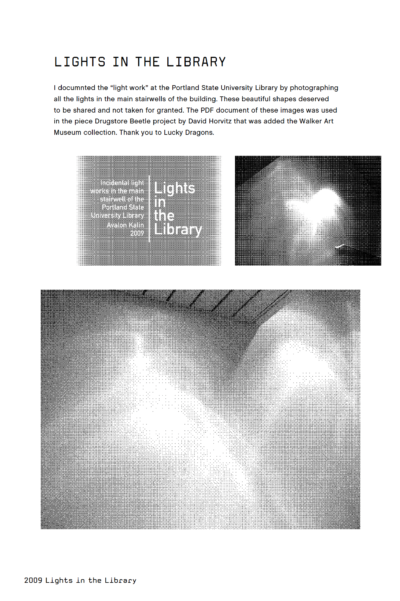

When I first encountered Avalon’s art, I was struck by the profound, deceptive simplicity of it all. Photographs of incidental light patterns in the library? A drum set drum circle? A micro sensory field trip? (The instructions read: Today, I went on a “micro sensory field trip” by laying on the ground and looking at what I found there. You should too. Lay down somewhere. Look right where your face is. Look right there. Observe the microcosm. Small things become huge. Walls are good for this too.)

With Avalon, small things really do become huge. There is a palpable nowness in his work, an identification of what’s here now, why it’s worth attending to, and how you can get involved. He’s really good at marveling, and he’s invested in making something you can marvel at together.

It’s especially exciting to witness this knowing that Avalon graduated from the first ever class of the PSU Art and Social Practice program, 2007-09, a time when social practice was just starting to be recognized in academic and art institutions, and was, at least judging from his prolific body of student work, more freeform and experimental as a result. In our conversation, Avalon dropped one philosophical doozy after the next, and left me feeling inspired to look deeply at the small things, and make them huge.

Becca Kauffman: So how did you find your way to the Art and Social Practice program?

Avalon Kalin: This is such a fun story. I love telling it, because it’s a true story of synchronicity, and I’ve heard that if something synchronous is happening, you’re on the right track. So the story is, I’m an undergrad studying design at PSU in Portland. I know of Miranda July, and I stumble upon her project with Harrell, Learning to Love You More, online. This site moved me so much personally. It challenged me, and then won me over. And then I had to reconsider my whole life. That night that I discovered the website, I wrote a map of my whole life on a piece of paper. You know, you put your name in the circle in the middle, and then you put branches off, like rays or octopus legs, and all the things that are important to you: family, art, music, health, romance. Just so I could like meditate on what the heck I was going to do. I was hugely affected. And I go to class the very next day, a typography class with Lis Charman, who’s an amazing designer and teacher at PSU. We’re sitting there, class is about to begin, she picks up a piece of paper and she goes, “Oh, this must have been leftover from Harrell’s class.” I said “Harrell’s class?” and she said, “Yeah, Harrell Fletcher.” I said “Harrell Fletcher? Does he teach here?” She said, “Oh, yeah, you should take his class, you would get along famously!” Oh my God, you know! Becca, I had no idea that he lived in Portland, I had no idea that he taught at PSU, and I had no idea that I could take his class. This is one of the strangest things that’s ever happened to me. When I took his class, actually, he said I was the first student he had who knew his art.

The first chance I got, I went up to him. I said, “Can I buy you lunch and ask you about your art?” He said, “Well, you don’t have to buy me lunch. I have to eat anyway.” And I just said, “Where did your art come from?” He always spoke plainly to me and he was always very generous. He’s been like a mentor or a friend ever since.

Becca: Everyone that I’ve known in the program found out about it in a social way, by someone just verbally handing off a suggestive seed that ended up growing into a whole new chapter of our lives, including myself!

Avalon: Don’t you feel like you’re invited by fate a little bit?

Becca: It’s funny, because when I look at your work I see a very Harrell-esque style and approach. There’s this clarified, direct simplicity. Your projects are sensible, but also philosophical. Is that the kind of work you’ve been drawn to from the start, or has there been an influence, having worked closely with Harrell?

Avalon: That sense of wanting something sensible, I really appreciate that word. That has always resonated with where I’m at as a creative person. This gets back to my interest in graffiti removal. In 1998, I began photographing it; in 2001, the film [I helped inform], The Subconscious Art of Graffiti Removal, was released, and it showed at Sundance, and that really opened my eyes because I was a writer of that. It was based on my creative practice, and it was so interesting to people. It got into the back of Art Forum magazine, and I was just a kid, you know, I was like, in my early 20s, and it opened my eyes that my ideas were valuable. And, you know, artist to artist, talking to you, Becca, I could see my way of being in the world was valuable to people. You know, how do you tell someone that your ideas come from the way that you walk around or who you are? It kind of doesn’t make any sense in this very appearance and productive based society. But I can see that now. I’m in my 40s and I see, oh, okay, my art practice came from the way that I responded to being in the city; what I was looking at, what I was seeing, how I was feeling. And only when I had a chance to communicate that, did it lock in that I could keep communicating with people about that. And so that’s very poetical, isn’t it?

When it comes to Harrell, it was as if someone had given me the go ahead to do what I was already doing. Jen Delos Reyes also encouraged me, saw what I was doing and pushed me forward. The title Student Work, on my book of student work, really comes from her identifying that my whole practice was very much like an apprentice to the people I was interacting with or what I was doing. It was a great lens to look at my work, all of it is just student work, because there’s a sense in what I’m doing, like you said, making sense of something and making it clear, and re-presenting it, that makes the whole world like a library, and makes you the curator of that library as an artist to bring it to people.

I would describe some of Harrell’s art as poetical action art, and I also describe Harrell’s art as coming from institutional critique. Watching a professional artist manage the context of their work through their words, through what they talk about and what they don’t in given situations, is fascinating. Harrell is presenting the world to itself, and trying to pin that down, that’s why it’s art. I think Harrell’s bias is towards documentary, towards using social practice to humanize — and this is my language, I don’t think I’ve ever heard him say this— but I believe myself that we are in an era of awakening to humanity, especially in the West. For me, Harrell’s art represents this huge philosophical shift of recognizing the connections we have to each other, to the institutions around us, to our work, to our life. Social practice is being connected to everyday life. That’s huge for me; you can see that in my work before I met him, and you can see how meeting him and doing the program was just a total license to ill. I did 40 projects in the two years I was there. It was two of the best years of my life. I always say that to people, because I felt really nurtured to do that.

Becca: How does your background in graphic design serve and inform your social art making?

Avalon: I was always interested in how I could use graphic design to get other people to participate in it. It’s an art form that’s very interested in communicating with the audience. Design often incorporates words, that’s one of the definitions of design, right? It’s art with words. So that relationship is always there. The design problem for me was, how can I use design to get people to interact with me? I think one of the great things that comes out of social practice is an emotional intimacy that’s not possible in other forms. It can be, but maybe it just opens it up to a range of experiences that you can’t find through other mediums.

Becca: So now, years out of the program and having been in the inaugural class, how do you explain social practice to people? How do you talk about social practice out in the world?

Avalon: I tend to call it social art. And I have a hard time. I have a hard time explaining social art to people. I don’t even get to social practice because I just have to say, you know, it’s art that involves working with people. And sometimes it’s public art, but it doesn’t have to be public art. That’s what I end up saying.

Becca: I’ve also chosen to use the term “social art,” because I think it actually does the job of plainly describing what it is more than “social practice” does. “Practice,” I think, confuses people who don’t run in art circles or something.

To what do you attribute the social nature of your art making in the first place? Why is that interesting to you as a central component?

Avalon: I like what Harrell said about it one time, and I’ll also say my version: “At some point, I discovered that I wasn’t that interesting.” At some point, I realized that what was going on around me was way more interesting than what I was going to find in myself. Now I say that only as a reaction to what we were taught art was, which is you have to reinvent the wheel, it all has to come from you, it’s the myth of originality. And we all know mastery is actually mimesis and copying very well until you find your own voice. And then what’s your own voice, but a way to advertise emotions? To be a part of something? It’s such a great question: why be social?

Becca: When your art is social, is your social artful? How is your art making integrated into your daily life? And your daily life integrated into your art making?

Avalon: I want to keep [the readers] very interested, so I’m gonna drop another big quote. So a really well known and beautiful poetic action artist, Mierle Laderman Ukeles from New York, came to PSU and she gave me a huge compliment when she was answering someone’s question. A friend of mine, a student at PSU who was an undergrad, Roselle Medina said, “What do you see is the future of the city and us being in the city? How can we reimagine the city?” Her answer was, “We must reimagine our relationship to the city. We must reimagine what a city can be. Just like in Avalon’s art, we mark the world by looking at it.” My heart exploded, my head exploded. I felt so seen and appreciated in that moment. Someone had shown a video that I had made about looking at the world. It was about seeing things that aren’t there, that are kind of there. I think you can apply that to everything that the artist is doing who is involved in everyday life. I would say it is a constant invitation. My ideal would be to wake up and walk around my neighborhood with a camera, and to come back and to make a book, or post something or make a video, or have a symposium or have an event at my house. I hope everyday to be able to do that.

Becca: I see this thread between your practice of deep looking, observation and noticing, and your spiritual life— which seems really active, I gather you have a strong meditation practice— and the documentary nature of your art projects. So I’m wondering how you identify a project inside of these daily ways of seeing and experiencing and how you turn your curiosity into a tangible idea?

Avalon: That deep looking practice was a way for me to synthesize the practice that I had that produced my art. My wife Posie really helped me to create the context so I could understand what was happening. I did the Walking School in 2016, and the Walking School is also a practice that involves what I’m now calling “deep looking.” Deep looking is based on the idea of deep listening, but for all beauty. The word “looking” doesn’t even quite do it, so I might have to change it. Pauline Oliveros coined the term deep listening after she released an album with some friends called Deep Listening. And the way she puts it is so amazing, she says that deep listening is a way to have beautiful experiences with sound wherever you are, by dreaming, by feeling, through listening, where your feet can become your ears, for example. I really resonate with this. I read The Ignorant Schoolmaster by Rancierre, and in that book, he says, the three questions an emancipated intellectual asks are: What is it? What do I think of it? And what do I make of it? I love this idea that there could be a recipe to just engage in something. So I wanted to share this as a practice, because that’s what was happening to me way back when I was walking through Portland and documenting graffiti removal, and putting that into zines. Deep looking has been a way for me to keep engaging in that as a practice and it marries really nicely with documentary art. My ideal would be, every time I engage a work of art, I have some aspect of everyday life included with it. I’m heavily invested in art and creativity in everyday life. And that’s okay that not everybody is, and I don’t think we should make social practice synonymous with art in everyday life. That’s not fair to everybody and it wouldn’t make sense, because social engagement has a wide range. But that’s really, really huge for me.

Becca: So making documentary art is how you catalog the everyday?

Avalon: I obsessively like to put very intuitive things into sensible situations, because it’s a marvel. And that’s what happens when you make a work of art, it’s something you can marvel at, even by stepping back from it, isn’t it? As artists, we want to be engaging with something that keeps going in some way. If I’m going to share, I have to invest time into the “what.” That’s evolving for me as an artist, I think it does with a lot of us, especially who have a range. It’s a problem for people who have a range. Now the opposite problem for someone who’s focused on a craft is, well, where’s my range? And then the problem with us is, I have a range, where’s this going to go? How can I present this? So the solution has been to create a practice that synthesizes these, and it’s still going.

Becca: I was curious about where your work is showing up presentationally these days. Because I’ve really only seen it in this compilation that you published of your student works in 2015, and also the documentation of your graduate exhibition, which, from what I can tell from the photographs, it looked like you kind of transposed and magnified all of these fine details from the cafe where you were an artist in residence into the gallery. I thought that was a really effective formalization of the time you spent there as an AIR. What are you working on right now?

Avalon: Before I answer that, and I have some that have happened lately that I want to share with you and the readers, and they can see some of the stuff and read some of the stuff. But first, I wanted to say that we can use this interview to do a short art project, if you’d like, I have a project that is based on a word game. Actually, this would be the only time that it had ever been performed publicly, if you’d like to do it. It was created by Norina Beck and myself. And it’s a word game, it’s very easy to play. And you can take this project with you wherever you go. And anybody who reads this can do this. So would you like to do that now?

Becca: Sure!

Avalon: I can answer the question. Then we’ll do the game. I was interviewed by The Stranger, which is Seattle’s main alternative weekly, four months ago about graffiti removal. I think people will appreciate that I was approached as an artist by a newspaper. And then I wrote an article for the Goethe Institut not too long ago about graffiti removal. This idea that everything we do has artistic merit is distinctly charming. Me and you could talk a long time about art, because the sensuous quality of art, I see that in your work, and also the transformational quality of sensuousness. And that’s kind of orbiting around the moment of the artists in the world, because it’s really sublime to do that. There’s that relational moment that can’t happen in other places. The documentary art is really to share that with people. That’s how people end up finding my work. Ideally, I would be an artist that was known to be spread through friendship. That’s what the situationists did, where they used to give their magazine for free by randomly selecting numbers and addresses— the whole sense of art really belonging to us. It doesn’t belong to the art world people. Art belongs to us.

Becca: You were going to introduce this word game.

Avalon: So this word game was created by my friend Norina. It’s a perfect game to play when you’re making food with someone. Breakfast, dinner. There’s two games: one is “Opposite of…” and the other is called “Is Like…” “Opposite of…” is where you say something, and then the other person says, “That thing that you just said is the opposite of…” and then they say something else. Then you take that and you say, that thing that they just said is the opposite of, and you say something else. So, you’ll see the fun of this game is that anything can happen. And actually, the less accurate, the more interesting and poetical the game becomes. One example would be a tree. And then someone might say, the opposite of a tree is roots, right? That’s very physical. And then someone would say, well, the opposite of roots is… today. And then another person could say, well, the opposite of today is timelessness. So it just goes wherever you want to go every time you do it. So do you want to try it?

Becca: Yeah, let’s try it.

Avalon: I’ll start with: walls. Now you have to say “the opposite of walls…”

Becca: The opposite of walls are… fields.

Avalon: The opposite of fields is… pine cone.

Becca: The opposite of a pine cone is… a dew drop.

Avalon: Beautiful. The opposite of the dew drop is a ray of light.

Becca: The opposite of a ray of light is a piece of coal.

Avalon: The opposite of a piece of coal is a train locomotive.

Becca: The opposite of a train locomotive is complete stillness.

Avalon: Beautiful. The opposite of complete stillness is American politics. [both laugh]

Becca: The opposite of American politics is…

Avalon: I’m so sorry for invoking them.

Becca: … Pure atmosphere.

Avalon: Yeah, pure atmosphere. Pure atmosphere is the opposite of… we’re stumping each other on this one. I gotta get out of this one. The opposite of pure atmosphere is… a carpet asking you to sit on it.

Becca: The opposite of carpet asking you to sit on it is… a surface that says nothing at all.

Avalon: So you can see this is a fun game. It’s just inviting you into metaphorical crossroads together, and the funny thing is, you can move around from being literal to funny to poetical to, you know, all of a sudden, something comes out of nowhere, and it’s just exciting and funny.

Becca: That’s great. I’ll introduce that into the program, I think people will get a kick out of it.

Avalon: I always thought this was a wonderful little work, because it’s something like a social work, you can pick it up wherever you are. Anyone can do it. In a way, it doesn’t exist unless you do it, which I also like… I think Norina probably invented it, and I was the artist who was like, this is an art project.

Becca: That’s one of the things that inspires me about your work is, what you just said, it doesn’t exist unless you do it. It’s a bold act to decide that something is art, and not many people would construe a kitchen game while you’re preparing dinner into an art piece, but by saying so, it makes it one. Do you have any thoughts about the way certain social projects of yours function as a kind of framework to pursue and explore relationships with other people?

Avalon: I am fascinated by the question because I’m worried about the antisocial nature of consumerist society. I’d never really dreamed that social practice would be a revolutionary act. And I’m afraid it might happen. I’m not too afraid, though, don’t worry. What I love about social practice is, I think it’s a tendency in art. The question for me exists in a space where we’re invited down the path of technocracy and VR, interacting through media. What I’m attracted to is to be together in ways that there’s live feedback in the live world. For me, social art is about the agency to give and ask and care about that question. To say, what does it mean that I’m even asking that? What’s my relationship here to the world? So the question is, what’s my relationship through my art? What’s my relationship to others and what’s my relationship to myself becomes what’s my relationship to the world? And this brings us back to my deep philosophical idea that we are all connected, everything’s connected, and we’re living in a time that literally doesn’t understand that, that’s still holding on to this Cartesian logic that believes things can be discreetly separated in a mechanical universe. And that’s all been debunked, but we’re still there as a culture. We’re waking up to reality, which is also an ancient reality. Can I use art to pursue a relationship? I’m like, oh God, yeah. Because the art process is a way for me to do that, isn’t it? I want to sit on that question forever.

Becca: Do you feel a connection between your spiritual life and your art making? Is there a direct line there for you, in how you approach it?

Avalon: Yeah, because spiritual life for me is quite simple. What I’ve noticed about my work is—and this is what you see all the time with your cohorts and other artists and yourself— this art is fundamentally about me being in the world and my relationship to being in the world and my relationship to the world. For me, it’s just that simple. I remember Harrell half-jokingly talking about this one time with me. He had some really ridiculous scale that he started off really small, and he was like, “And this thing is just advertising this thing and that thing is really just advertising that thing,” and I think he might have said something like, “Well you know, the flower’s advertising colors and petals,” and he went all the way out to like the whole universe, you know, it’s just advertising this universe really. It was hilarious. And it’s so true. Spirituality for me is being here with you, it’s just being alive and knowing that that is more important than how I appear, or what I produce.

In the city, the secular cities and institutions, people hate the spiritual stuff, because there’s so much baggage with spirituality and religion has been abusive, really, right? So I get it, I get the reaction against spirituality. But the truth is, spirit is a word for the profound experience of being alive. You could say, “profound emotional and psychological experiences,” or you could just say, spirit.

Becca: Do you have any favorite quotes to share?

Avalon: This is from way back. Here’s a good one. Paul Klee, he said— and social practice really understands this: “Art does not make visible things. Art makes things visible.”

Becca: Wow. Yes, noticing is an artform in and of itself. Art is like one big arrow.

Avalon: I love it. And so there was an introduction written by Sibyl Moholy Nagy for this Paul Klee book, Pedagogical Sketchbook, and she quoted [the poet] Novalis and I’ve never found this quote anywhere else: “Give sense to the vulgar. Give mysteriousness to the common. Give the dignity of the unknown to the obvious. And a trace of infinity to the temporal.”

Becca: Are these guiding lights for you in your own work?

Avalon: Oh my god, yeah, this quote just resonates so much with me. I can just meditate on this as what’s happening in the art that I love… It really comes down to, what’s alive for you right now? What’s alive for me is “give sense to the vulgar.” Because, first of all, what’s vulgar? What does that mean? Disgust is a powerful emotion. It’s almost autonomic. Don’t think anybody’s above it. Everybody has something that’s vulgar to them or that they’re disgusted with. So the idea of “give sense to the vulgar” is very interesting.

Becca: “Give sense to it.” Like, name it, notice it, realize what’s there and what are you pushing up against, what feels challenging or repulsive… And what kind of indoctrination is involved in that, or subjective felt experience.

Avalon: Yeah. So bringing that awareness in, that’s what poetic documentary art gives me a chance to do. I am so grateful meeting someone like you who sees the range of my work, you know, who sees the different things as being valuable, because some people will see one thing or the other, but seeing multiple things, it’s like, Oh, I see what you’re on about. I took pictures of the lights in the PSU library. They were beautiful to me. I took the photographs and I printed the photographs and I put that in the book. To me, that’s the “dignity of the unknown to the obvious.” Literally, let’s bring lights into this photograph. Everytime I walked in the stairwell, the invisible was being spotlighted, in that sense. But I ended up going into the spotlight by taking pictures of them, I guess. It’s like the artist is carrying around a lamp, and the art is a way for them to bring that lamp space back to other people. It’s very interesting, because when you start to separate, well, where does life end, and art begin? That’s really what’s happening.

Honestly, the staying power of this stuff is its subjective value, its poetic value. For me, the real value is talking about the stuff that we’re talking about. As somebody who’s been through the program and looking from the outside, or anybody who’s reading this, it’s the meaningful experiences that are the purpose of the work.

Avalon Kalin (he/him) is a graphic artist who makes documentary and social art connected to everyday life. He is the co-author of “The Subconscious Art of Graffiti Removal” film produced by Matt Mccormick and he studied under the first Social Practice MFA program with Harrell Fletcher and Jen Delos Reyes at Portland State University. His work has shown in institutions and perhaps more importantly between friends. He collaborates with his wife Posie Kalin designing installations and products. Recently, he founded The Walking School. Find more about his work at avalonkalin.com. Recent shows and projects are on instagram @avalonkalinworks, and you can read and subscribe to his newsletter, Deep Looking, at http://deeplooking.substack.com/

Becca Kauffman (they/them) is a social artist based in Portland, OR and Queens, NY practicing art as a public utility through interactive performance, devised gatherings, and neighborhood interventions. Their work has taken the form of an unsanctioned artist residency in Times Square, a public access television show, T-shirts functioning as conversation pieces, a pedestrian parade with a group of fifth grade crossing guards, and the persona-driven musical performance art project Jennifer Vanilla. A member of the experimental Brooklyn band Ava Luna for ten years, Becca is currently an MFA candidate in Art and Social Practice at Portland State University. You can listen to their new Jennifer Vanilla album Castle in the Sky wherever you find music. @pedestrianvision @jennifervanilla

Visual Intentions

“I really like the capacity for art to ask questions as opposed to trying to answer questions.”

Eliza Gregory

I wanted to be a photographer and then I didn’t. Well, that’s kind of true. I have always wanted to take photos because I believed they were the fastest way to make, share, and keep beautiful things, especially beautiful things that were too expensive to own. I studied photography in college and before I graduated, I told my classmates and professors that I wasn’t going to earn a living from it. (I wish I had thought to ask myself what I would do instead but eventually I figured it out. Kind of.) If you asked me why I didn’t want to earn a living as a photojournalist or commercial or editorial photographer— all of which were natural and available next steps after graduating— I would’ve told you that I couldn’t stomach anyone directing how I saw and photographed the world; I only wanted to see what I thought was in front of me or what I created with other people. While I adore my undergraduate professors and think of them daily because of the work ethic and technical skills they taught me, I wish Eliza Gregory had been in my undergraduate life. I imagine how the development of social practice as an art, along with her collaborative and participatory project experience, would’ve helped me develop a career for myself as an artist and photographer sooner and more confidently. After our conversation, it was clear to me that while I consider myself an artist, I’m as much a photographer as I ever was and ever wanted to be.

Eliza Gregory: Hi!

Laura Glazer: Hi! So nice to meet you.

Eliza: Likewise!

Laura: Thank you for making time to talk with me.

Eliza: Oh, of course. It’s fun. I wanna hear about your New York Public Library Fellowship. That sounds so amazing.

Laura: It was amazing and I feel pangs of missing the place and the people.

Eliza: How long did you hang out there for?

Laura: I was there for three weeks. I gave myself one of those weeks to acclimate, so it was really two intensive weeks on-site in the library’s Picture Collection. I will return in March to launch the publication or at least do a work-in-progress presentation.

Eliza: Tell me a little bit about it. I am so curious. I want to hear about that because I’m teaching my students right now about visual research and also thinking about how to integrate that into my own projects. And it’s just fun hearing about what you found and what you’re making from it.

Laura: Well, I went there for the first time in 2018 and I casually gave them my business card and said, Contact me if you ever need another person to do an Instagram takeover. And they did! So in 2019, I did a takeover of their Instagram using the digital collection from home in Portland.

Eliza: Cool.

Laura: Of course, I had this deep desire to know what it was like to actually be in the Picture Collection doing research—do people talk to each other? Are people looking at what everybody else is looking at?—I had this longing to know what it was like to physically be in the place.

Last year I spent a lot of time researching the Picture Collection and Taryn Simon’s project on it called The Color of a Flea’s Eye. Then in November 2021, I visited New York and stopped by the Picture Collection to say hello to the librarians and to see Simon’s exhibit.

A few months later, I interviewed Jessica Cline, the Picture Collection director, for the Winter 2022 issue of SOFA journal and she mentioned that they were launching a fellowship. I applied and was accepted as one of four fellows. My project evolved while I was there and I’m calling it See Also, a phrase that comes from a library term for a cross reference.

Eliza: That’s great.

Laura: Instead of researching a subject heading within the Picture Collection, I essentially researched the researchers.I started with what they were researching, and then went into a “see also” of, Oh, you’re researching Mary McLeod Bethune? What else do you do? Oh, you design custom flamenco dresses. Great. Can I come to your studio and see them? Okay. I’ll see you on Monday.

Eliza: That’s so rad. Oh my God. I love it. I’m like an—I don’t know what we’re calling it—affiliate or something of this new foundation called the Flickr Foundation, where Flickr, the photo platform has gotten some money to try to make a 100 year plan to think about what it means to conserve the 50 billion photographs on Flickr right now! What does it mean to treat that as a site of cultural heritage and actually think about how it is preserved going forward?

Of course, the way I think about it is like what you’re doing there. When and how do those pictures come back into the world? Or when do they become objects? When do they stay digital? How do people use them? How are people interacting with them? One of the great things that George Oates—the woman who is the head of the foundation—is talking about is, What’s the role of ritual in communication and is there a ritual-like translation that happens every few years from whatever the current format is into the next format? Because that’s what’s happening all the time, you know? Are we even gonna have JPEGs in a hundred years? What’s gonna be the equivalent mechanism for accessing visual data? So from what you’re saying, I’m like, Oh, this is so great! It ties in with other random things I’m thinking about. I don’t really know how they all come together in my own practice.

Laura: Well, that is one of my questions for you. Where are you right now with the intersection of photography and socially engaged art? That’s a big question and I just asked it casually like it’s small talk!

Eliza: There are a few different ways I talk about it.

In my own practice, I was really interested in telling stories about people. But as soon as I started to do that, I ran into all these ethical questions about the objectification of a person. When we literally make an object out of a person—the photograph being the object—what are the ethical implications of that? I started to solve those problems or engage with those questions through social practice mechanisms. That’s how I got to social practice, because I just started to build out the relationships and the accountability and start questioning each choice that you make in the process of representing another person or representing a story. Then through that interrogation, I started to have more and more other stuff going on in my work that was not the picture, but that still was connected to the picture. That’s what I really look for now when I’m engaging with other photographers’ work—what is happening outside of, around and beyond the picture?

I think photography is such an amazing tool and it’s used in so many incredible different ways now. Sometimes I have an optical engineer come into my History of Photography class, and he talks about all the different lenses that go into a Roomba or all the different lenses that are inside of the way we read COVID tests.

Photography is everywhere and trying to say anything clear about it is really hard because it can mean so many different things. Along with that, we’re inundated with photographs. We look at them so much. I feel like the historical fine art photography dialogue of the last 70 years or so—where there was this big fight to make photography be seen as a fine art and then to fetishize it—has become really obsolete. That dialogue was all about telling a story and having layers of information in the frame and this myth that you could get a lot from the experience of simply looking at a picture with nothing else going on.

Now I think it’s very clear that a picture can mean one thing in one context, and the same picture can mean the opposite thing if you have slightly different information surrounding it or a slightly different location that it’s being viewed in or a different caption or a different picture that’s next to it. I really believe that to make art using photography right now involves really engaging with the context in which it’s going to be viewed, which includes thinking about the audience that’s going to see it. What does that particular audience bring to that experience and the location it’s going to be viewed in, and the visual material that’s surrounding it; all of that has a lot to do with social practice.

I think the people who are making the most exciting lens-based work are engaging with all that stuff. They’re engaging with the context, the audience, and they’re also engaging with all these other aspects of making art that are happening around the picture. And then there’s still a picture sometimes in there somewhere. [Laughs]

It can be really good. Pictures are still really amazing and really fun to look at. They do communicate a lot and they are powerful. I think that’s why it’s so much fun to be engaging in these questions—photographs can accomplish so much and they’re also so limited.

Laura: In what you were just saying, I imagine the picture just getting smaller and smaller and smaller and the people in the picture getting bigger and then the image is super tiny. The image is becoming less and less of a focal point.