Fall 2025

Letter from the Editors

Second Year Crew: Sarah Luu, Gwen Hoeffgen, Domenic Toliver and Adela Cardona Puerta

One of the things that consistently stands out in our program is how our work is informed by those we surround ourselves by. Each of us comes with a different set of experiences, questions, and personal connections, and those differences shape our practices in ways that make them unmistakably our own. At the same time, we often find ourselves drawn together through shared experiences, interests, and processes.

This issue brings together interviews that follow those threads: the ideas we return to, the places that ground us, and the people who walk beside us. For some, literature became a site of connection—reading as a way of relating to others, or books as companions that open unexpected routes into our work. Others found themselves seeking alternative modes of expression, experimenting with forms that offer new possibilities for communication and understanding. Many contributors reflected on learning through lived experience, letting life itself act as a teacher.

Across several interviews, we also see a reconsideration of the tools we rely on. How can the same tool take on different purposes depending on intention, context, or care? Many conversations touched on the importance of praxis, the effort to align what we practice with what we believe, and to walk the walk and not only talk the talk. Themes of inner awareness, vulnerability, and the willingness to be misunderstood recur as well, along with honest reflections on anger as a meaningful way of navigating the world. These interviews invite us into alternative ways of sensing, thinking, and interpreting what surrounds us.

One of the most prominent themes this term is friendship. Many contributors chose to speak with friends, collaborators, or peers—people who have been present in their lives not only as fellow artists but as confidants and supporters. These conversations highlight what it means to show up for one another, to share resources and experiences, and to grow alongside someone else. The issue reveals how friendships, both longstanding and newly formed, can shape creative practices just as profoundly as any formal study.

Each term, this journal gives us an opportunity to reflect on our practices through the act of conversation. Interviewing—listening, responding, wondering aloud—offers its own form of discovery. While patterns inevitably emerge across issues, each interview remains distinct: its own world, its own rhythm, its own exchange.

We hope you enjoy this fall’s issue of the Social Forms of Art Journal.

Teaching a Painting

Simeen Anjum with Tamia Alston-Ward

“The fact that you can’t read it all forces you to want to read what’s in there… There are creative ways you can educate about Black historical subjects which are being erased from our curriculums. Art is a wonderful gateway into educating people on not only contemporary, but historical, political situations and environments.”

During my summer internship in Adult Education at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, I found myself drawn to the dynamic conversations happening just next door at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where an educator institute was underway. It was there that I met Tamia, a gallery educator. I was struck by Tamia’s ability to cultivate an atmosphere of curiosity and critical engagement during gallery sessions, creating space for young learners to explore art in meaningful and thought-provoking ways. As someone exploring museum education across different institutions, I’ve been interested in how various museums approach learning in their spaces, what supports meaningful engagement and what insights I can bring into my own practice.

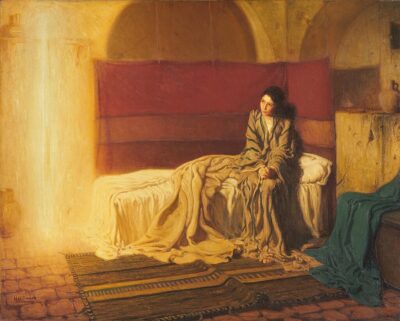

In this interview, I speak with Tamia about her role as a K–12 educator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the challenges and opportunities of working in museum education today, and what it means to teach art in a city as historically rich and complex as Philadelphia. We also delve into the work of Philadelphia-born artist Henry Ossawa Tanner, whose painting, The Annunciation, offers a historically grounded and deeply human take on a biblical scene, an entry point for considering how museums can foster more accurate, inclusive narratives.

At a time when public education is facing increasing censorship through restrictions on teaching about race, gender, and LGBTQ+ issues, museums may serve as critical spaces for dialogue and reflection. How can they support more honest, expansive conversations about history and identity? Tamia shares insight into the power and responsibility of museum educators to engage students in this important work.

Simeen Anjum: What is your favorite painting in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) that you like to talk about as a gallery educator?

Tamia Alston-Ward: I would say the Annunciation by Henry Ossawa Tanner. I have a connection to the artist through the alma mater (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts).

Simeen: Is it the one he painted in Palestine?

Tamia: Yes. I love this painting and I still teach it over and over again. And what’s cool is that it’s opposite another Annunciation painting from the Baroque era by the Spanish artist Zurbarán. It’s a great contrast and shows the differences in how the story of Mary, Jesus’ mother, is depicted across time. Tanner’s is from 1898. Zurbarán’s is from 1650.

What I love most about the painting is the expression of Mary. Tanner was really focused on historical and biblical accuracy. There are so many depictions of Mary, in the museum and around the world, but none quite like this one. He traveled to Palestine to study the architecture and the people because that’s where Mary and Jesus were from. There’s a long history of Black Christian presence here in Philadelphia that Tanner and his family were part of. His father was a bishop and the family published hymnals for churches.

Henry Ossawa Tanner: The Annunciation (1898)

But what I really love is how Tanner shows Mary in a way that I wish everyone could see. All the other versions of Mary just aren’t accurate. You can see the realism in her expression. She looks concerned. In the Bible, when Gabriel tells her that she’s been chosen, there’s a moment where she accepts it. And the expression on her face here makes it seem like she’s still in that moment, still figuring it out. She is not yet wearing the colors blue and red that symbolize her role. You don’t have to believe in Christianity to appreciate that these were real people from a real part of the world, a part of the world that’s currently experiencing real hurt, pain, and hardship through genocide. We forget that the religious figures we revere came from that area.

If I were to go online right now and search “Annunciation,” there would be so many images and almost all of them would show a much older Mary, a much whiter Mary. The architecture would be European, the curtains, the setting, the clothing, it’s all inaccurate.

The Zurbarán painting is across from it, so we do a compare and contrast activity. I’ll bring the visitors to both and use a Venn diagram. We talk about composition—Mary is on the right, Gabriel on the left, in both. But we also look at architecture, clothing—“Do you think they wore this 2,000 years ago in Palestine?” The answer is no. Definitely not. So when I show students these paintings, I ask them: After seeing this and the Zurbarán version—which one feels more accurate? And they always point to Tanner’s.

Francisco de Zurbarán: The Annunciation (1650)

All this is to say that art helps us discuss political and social issues, both from the past and today. Zurbarán’s painting is from 1650, after the medieval period when all art had to be religious. The Baroque era was dramatic and theatrical, artists were showing off their skills with drapery, perspective, etc. And the paintings were meant to depict the Bible for people who couldn’t read. But Tanner had the opportunity to travel. He made this painting in Paris, after studying at PAFA and trying to escape racism in the U.S. And you can see how that experience shaped his work, his faith, his clarity, his honesty. I think he made that painting for himself.

Simeen: I’m curious about how the Museum Educator role differs from the Docent role, and in what ways these positions overlap or collaborate. I’ve noticed that many museums are moving away from traditional docent models and shifting toward more learner-centered approaches to engaging with art, rather than strictly information-based methods.

Tamia: The docents work on a volunteer basis. And as educators, we’re constantly looking at work like, “Okay, how do we talk about different artworks to students? How do we talk about nudity?” etc. We have discussions on how to best go about teaching in the galleries. We also create the teaching resources and plan how objects of different cultural backgrounds should be taught about.

Simeen: I feel that traditional docent-led tours often don’t require deep critical engagement with the collection; they tend to focus more on familiarizing visitors with what’s on display. But museums are increasingly reconsidering how valuable it is to simply present the history of an artwork versus helping visitors actively engage with it, especially when working with visiting student groups.

Tamia: Yeah, a lot of people who come to the museum are first time visitors, so we do a lot of highlights tours and it kind of lends itself to sameness. But the museum has been making an effort to make sure docents receive training from the educators. And they’ve done some of our K–12 tours for us, and they have great relationships with us and the students. But there was a time when an object was taught that was different from what we wanted it to be taught. It was a piece by Barbara Walker. She’s a draftsperson and she makes these drawings where one person is primarily drawn and the other is embossed.

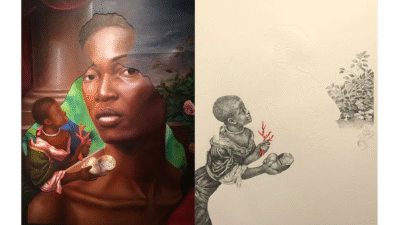

From left to right: Seeing through Time, Titus Kaphar; Vanishing Point 24 (Mingard). Credits: Héloïse Le Fourner

So this painting right here is Titus Kaphar, and this drawing right here is Barbara Walker, and they were situated in the gallery opposite each other, so they were facing one another. They are both referencing the same artwork, a European piece by Pierre Mignard of a woman. And you can kind of barely see her in one, and then she’s cut out in the other artwork. And we see only the girl who was enslaved.

We discussed amongst educators: are we going to show the students the image that both of these artists are referencing? And we decided not to. The reason being that both of these artists intentionally cut out this European woman from these images—they’re both referencing the same image, but they are both removing, intentionally, the European image. It was in the section of the exhibition called ‘Past and Present’, it was a section dedicated to reclaiming history, basically, and contextualizing history in a different way.

So, I think one of the educators noticed that one of the docents had brought the laptop to the exhibition just to be able to show the Mignard piece to the visitors.And when we heard about that, we rolled our eyes. But again, it’s really up to the educator’s discretion if they want to do whatever they want to do on a tour. They really insisted on showing the image. And I think the main kind of discussion around these pieces was: why do we insist on showing the white figure?

Why do we need to see it, when we already can assume what she looks like based on just the outline here, this embossing and the clothes.

If you just go to the third floor of the museum, you’ll see a lot of Regency, aristocratic European figures everywhere. And the real reason why we didn’t want to show these is because this girl here is enslaved. This is a picture of a woman who is a duchess who had a painting by Pierre Mignard commissioned for her, and it was depicting her with her arm around this enslaved person. When we interpret it to the kids, we ask them close-looking questions: “What do you see?” “What do you notice?” A lot of the time, they’ll say ‘some mom and her kid’ or if it’s not a mother, then maybe it’s a sister. Because of the nature of the way the images are arranged, it makes the students think that the relationship between these two figures is tender.

But it also allows for a conversation around propagandistic imagery of the “benevolent slave owner” imagery. In the 1700s it would have looked like a really pretty, beautiful painting. But was that relationship really what it is in the painting? No, because this person was owned. And it’s another reason why we would not show the image of the woman because it’s not about her. Barbara Walker, in her drawing, makes an effort to render only the things that are relevant such as this little girl here. And Titus Kaphar in her artwork manipulates the canvas to physically cut out the woman. And then he puts a painting of another canvas inside, depicting the woman, in a way that you can’t tell who she is. So a lot of times in the galleries when we ask students “Who do you think she is?” Most of them reply with, “Maybe it’s the little girl grown up,” “Maybe it’s her mother,” “Her actual mother.”

Simeen: I am sure a lot of great discussions come from this. Has there been any other artworks lately that have allowed for more critical engagement within the museum?

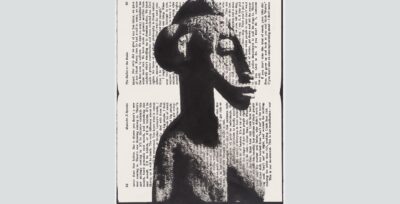

Tamia: Yes, this work from Brand X, a screen printing collective based in New York. And it is a piece depicting an African sculpture superimposed on an open book, that is oriented vertically, but you can see both the pages. It’s from a speech made by Malcolm X called ‘The Ballot or the Bullet’. My colleague, Cherish and I chose that image because we thought it would be great for teachers to understand that they can use this as a jumping-off point to talk about things that may be frowned upon by their administration. and then imposed over it, you have this African sculpture taken from 1970s “primitive” African works. And there’s no context, there’s really not much there that the artist, in the description, is telling you about the works. But there’s a lot that you can interpret from there. You can think about censorship, because you can’t see all of Malcolm X’s words. The fact that you can’t read it all forces you to want to read what’s in there. I think for students, it’s a great gateway for them to learn about many things. Learn about African objects, and why they are without context in certain spaces, anthropological context, but not in a formal or spiritual context. It makes you think about why there would be an African object mixed in with Malcolm X’s words, what is that connection? You could ask that to the students and have them research about Malcolm X as a historical figure, and this piece as an artwork. What I really enjoy about that piece, is that there are creative ways you can educate about Black historical subjects which are being erased from our curriculums. Art is a wonderful gateway into educating people on not only contemporary, but historical, political situations and environments.

Adam Pendleton: Untitled (Figure and Malcolm), 2020

Simeen Anjum (she/her) is an artist and educator based in Portland. In her practice, she explores new ways of fostering solidarity and community in response to the late-capitalist world that often isolates us. Her projects take many forms, including sunset-watching gatherings, resting spaces in malls, and singing circles in unexpected locations. She is also interested in learning and engagement within museums and art spaces. She has explored this through internships at several institutions, including the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, the Partition Museum in New Delhi, and the Littman and White Galleries at Portland State University. She currently works as a K–12 Learning Guide at the Portland Art Museum

Tamia Alston-Ward is an artist and educator based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her artistic practice is deeply rooted in research and the study of material culture in the Black Diaspora. She has worked as an educator in the National Liberty Museum, Malcolm Jenkins Foundation and currently serves as the Art Speaks Coordinator and Museum educator in Philadelphia Museum of Art.

A Ripple Effect: Public Architecture and Building Collective Futures

Gwen Hoeffgen in conversation with Sergio Palleroni.

“Replicability is understanding, and analyzing, the system rather than thinking that the system doesn’t work. How do we make the system work to serve the people? And how do we rethink it so that it can be repeated?” – Sergio Palleroni

I first started thinking more deeply about architecture after reading In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado over the summer. In the memoir, Machado uses the house as a metaphor for her body, telling the story of an abusive relationship through the shifting rooms of a “dream house.” Reading it made me think differently about what a home can represent. I began reflecting on my own relationship to home, thinking about it as something intimate and embodied—almost like an extension of the body itself. I started wondering about what happens inside domestic spaces, who holds power there, and what the walls of these spaces hide.

This curiosity led me down a larger rabbit hole around architecture of the body and the idea of building together. I became especially interested in how people collectively create, lose, and return to “home.” While working on If We Could Talk, a project focused on displacement in Portland and the experiences of people who have returned to the area through housing bonds, I started thinking more seriously about the role architects play in these processes of negative and positive change in neighborhood communities. I became interested in what it might look like for architects to truly listen to communities, rather than design from a distance. I wanted to interview Sergio Palleroni because of his long history of public architecture projects that center community voices and socially engaged design. His work approaches buildings not just as objects, but as systems shaped through conversation, care, and collaboration, and his methodology mimics socially engaged practices that inform my own art practice. In this interview, we talk about architecture as a way of deeply listening, storytelling, and building the future with rather than for communities, and how a building can be more than an object– it can produce positive social change and strengthen relationships.

Gwen Hoeffgen: I researched many of the projects that Center For Public Interest Design has worked on, which led me to research the many projects in your portfolio. There are times in your work where you have described architectural structures, like buildings, as systems. I thought it was interesting because I think of socially engaged art projects, especially through a social justice lens, as being a way to create systems. Could you talk about that language, and how a building could also be a system?

Sergio Palleroni: You can think about architecture or the building in the environment being so dominated by a series of very structured hurdles to go through. There becomes an emphasis on building this one object. But, when you put this object in a community, it has a huge impact. For us, the thinking about the system is that the building will have a ripple effect. As a building is introduced, even if it conforms to aesthetic and expected values, will still have this ripple effect on a community. That, for us, is the system.

Also a building generates and activates all sorts of non-monetary assets in a community. So, a particular building will provide X number of jobs, or it will provide security, or cultural activities which can be important to the health and wellbeing of the community. So we are trying to rethink the field in order to educate people on how architecture could be a way to address social problems. Not just in the programming, but even in the way it’s built. Potentially in the discussion and process of building, the community can guide its investments so that there is a greater impact on the needs of the community.

When I got out of architecture school, I wasn’t even taught how to talk to a client. The drawings and models and everything you do are very beautiful, but they’re also only addressing a certain segment of the community that can understand those drawings. Really, 95% of all the drawings are impenetrable for anybody but an architect. So, it’s an exclusionary act. And we haven’t been very good about figuring out ways that we can embed ourselves in the communities and discuss its needs and things like that. How can we become more of public architects?

So we think about the system as a way to bring in all that we’ve left out of the process. Through discussions, you can affect what you have an impact on.

Gwen: The processes you’re talking about seem so similar to those in socially engaged art processes, which rely on deep listening and response to people. I listened to a podcast you spoke on, and you talked about this process of an architect as a “curator”. How are these “systems” as buildings developed using response to community?

Sergio: Let me give you an example. We are looking at housing very deeply. We spent like 30 years looking at informal settlements, in Mexico City or Africa– all over the world. We would go in and if the community needed a school, we would sit down with the community and figure out: what is a school to this community? And then we would try to figure out if the community may not have the traditional means to get the school done, but what assets does it have? And with those assets, how do we get the building that they want? So it might have been produced in unconventional ways– maybe people would collect bricks. And maybe the classroom is not the kind of thing that shuts down at three, but then has a second life as a community center. If a community is going to invest so much money to build a school, it has to address more than just education. So we’ve had instances where the school becomes a women’s center, where women have micro industries. Or we’ve even had schools that have become the infrastructure for the immediate neighbors–they’re providing waste and water, electricity, and everything else. Or we’ve had schools where the gardens become a way to protect the local species and native environments. And, in doing so, the landscape becomes both a playground for kids, but also a place to teach environmental education and cultural values and things like that.

Gwen: The way you’re describing this sounds like a form of creative problem solving, and also it sounds very imaginative. We have such strict and narrow categories for the function of architectural spaces in which we normally abide by – a school has to be for children, and we shouldn’t live in cars– but I like the idea of reimagining and literally building a new reality, and a new way of how these spaces can function.

Sergio: We have a seminar in the graduate certificate, where we go through and we look at the different challenges– like issues of inclusivity, or issues of how to do public practice in states of emergency, or when you have to reimagine society. So in our coursework, we try to expose students to different strategies so that they become aware that the role of an architect is broader. You were talking earlier about the creative process, and the process of doing architecture, and art as well, is maybe the most powerful tool. So now, Stanford, Yale, and MIT’s business schools all have design schools within them. That’s because design thinking can unite and cross between disciplinary boundaries. An economic issue and a social issue can be put on the table, and they can both be relevant to the act of creating a building. Even if you decide to become a filmmaker, you’ll carry over this idea that everything is somehow connected and taking things out of the basket may not be the best process. At first you may just have to throw out a broad net and see what all these things are and how they’re related, and figure out a way that we can see the interrelationship between them. And then, with the community, you can begin to weed out what’s unnecessary.

Gwen: Speaking of your pedagogical practices, can you talk about the importance of replicability in your work? And how teaching these socially engaged methods of building could lead to replication?

Sergio: Sometimes they’re one off, like this community center for the Mongolians, and it ends up inspiring others. The villages through Northern China, Central China, and Mongolia, are all suffering from the agricultural system becoming industrialized like ours. 30 years ago, 80% of the population was agrarian, and a lot of people are moving into cities to become industrial workers in China. But most of the population are either too old to make that adaptation, or culturally they can’t adapt to that. The idea was to rethink these villages and keep people in place in a sustainable way, and they could keep their relationships to the land. This was considered a successful experiment, because the cultural values to the land and deep philosophies of sustainability were represented in this effort. We asked, how could we embody this? And how could we rethink these villages so that they stay viable in the future. It has been repeated because there’s a way for the villages to remain–or maybe it’s a vessel in a way– where sustainability is their bridge to that, and their culture is a bridge to the future. So replicability sometimes happens because we clearly state the values, we involve the community, and the community understands those values– and they will then become proponents for future work. That’s one way they replicate.

The other way they replicate is, for instance: we did this process around homeless housing that led to the villages. We were approached by the coalition of the homeless, they called themselves a congress, and they were meeting at the Rebuilding Center. There were representatives of the major communities and street families, and they said we need to change the narrative on this, and we need the government to step in. And, they said it shouldn’t be just the housing thing, because the problems are more complex. And they had begun to have some experiments which were successful– They had built the first village with the support of a series of activists. And we knew that that was beginning to be a solution. But they wanted a solution that the city would’ve considered. So we said, what we need to do is we need to create a process of doing this that will begin to bring the normal actors involved in this into this problem. So we invited the Congress, which was made up of like 150 homeless people representing the community, and we invited the 12 largest and best known firms in the city, through relationships we had personally, to the gallery below Mercy Corps. We told them you’re going to come to an unconventional thing– you’re not going to be sitting around for investment money, you’re going to be sitting with the homeless. Artists and architects are utopian; we are believers that it would work, you know. So we sat them down for a weekend. We ended up coming up with his design and then we invited the mayor. And, he didn’t know what he was getting into. He walked in there and there were like 500 people in this beautiful building– and we ambushed him, poor guy. We presented the designs and of course he was asked to be part of the final review. We said, wouldn’t it be great if the city did something, after you’ve acknowledged that there’s a crisis in housing. The governor had declared a state of emergency, and here’s an opportunity with all of the key planners and architects in the city. So we forced them to fund the building of this first village. And, he said that there was a whole bunch of land at the city warehouses for future development. Because they were going to be temporary structures, I had a brilliant student at the time, and she figured out that if we kept them to the size of the food carts, then we didn’t have to get a permit as long as we didn’t have bathrooms and as long as they were mobile. We triangulated all that and we came up with a kind of approach to temporary emergency housing. And we found the holes in the code to allow us to do this. And we decided that the first people to deserve it should be women, because women living on the streets are most impacted. And then at Christmas, we decided to have a street of dreams right on the North Park blocks and then we invited people, and thousands of people came out to see all these beautiful houses done. And, the mayor had given us a site and he said, let’s just put ’em up. And I said, well, no, because we want to create a replicable process, so we need to engage the community, which was the Kenton neighborhood– a lovely neighborhood and middle class– not rich, but full of a lot of assets. So we’re going to engage them in this discussion of what it would be like to have a community of homeless living together. So for over three months we sat down with the community and said, okay, we are going to introduce this site– What does that feel like? We started to form the motions. And we discussed that they are people in need, but they also are bringing assets. We could have a site for a Saturday market, and community gardens introduced, which would allow you to meet and collaborate over garden plots with each other. And it was right across from their main square, which they were very proud of. So we took them through this whole process and then we invited the mayor in for a discussion and the mayor said, we don’t have to have a vote. But we insisted on having a vote because the land is owned by this city. Because it was a temporary installation, we didn’t need to be permitted for it, but we insisted on formalizing the voice of the community. So we took what would be traditional planning and everything, but made a public version of it where more people would be involved, the community would be involved in harmony, which normally would just be the city behind closed doors. When we came to a vote, I thought we were going to lose the vote because people were so angry and frustrated, and I think this was mostly due to the system in which the government operated. But when it came to the vote, it was 168 family units against 93. So it was a strong vote. And we said in a year, we’ll revisit the vote, we’ll see how it goes and how the services play out and everything. A year later we did the same vote and only three families were against it. 312 against three. So the success was the community accepting, but when they formalized it, the community was up in arms. They said, we love having the homeless community here. They fought for, and they bought, a piece of land in the community so they could have a permanent home for the homeless village. So, it moved down like two blocks. So to me, replicability is understanding, and analyzing, the system rather than thinking that the system doesn’t work. It’s how do we make the system work to serve the people? And how do we rethink it so that it can be repeated? It’s not that the permitting process is avoided– it works, but you just haven’t thought about it in terms of the situation.

Gwen: I think I have another question regarding architecture and repetition– specifically in regards to Portland’s history of urban renewal, racist land policies, and gentrification, which have occurred multiple times in Portland’s history. I see some architectural attempts to produce community movement to bring people back to areas where they were previously pushed from. For example, in the Northeast, where Albina became greatly gentrified, there are new housing developments prioritizing Black families that have historical ties to the area– they are bringing people “back home”. I am interested in what your thoughts are about harmful urban renewal, like the 5 freeway, but also in this idea of the return to community that is very different than it once was.

Sergio: Yeah. Going backwards is hard. We did the initial public profits for the Albina Trust. We called it Right2Root. We had these meetings where we inscribed abstract trees in plywood. Below were all the things that they carried value and the branches and the tree above ground became what their future was going to be. They got to put in their ideas, then we would talk about their future, week after week. I was very hopeful because, we’re thinking, we’re gonna return. Returning is very powerful, but what does it take to return? These buildings are being done, which are the outcome of Right2Root. But the problem that the community is having is that you can’t just build a community. You have to include the community in the process. It can’t be just the people that are gonna be served by that building, but how would those buildings serve the larger community. Right now, it’s a moment where more consensus building needs to happen and there are powerful forces behind Albina’s processes toward that future. We started the Afro Village– that was our baby. They were decommissioning the light rail cars. They came to us and said, we have 52– What can you do with them? They knew we did a lot of mobile urbanism. So, keeping everybody aware and connected and participating in the Afro Village as it moves forward has been a challenge. It’s a discussion that needs to be had. It can’t just happen at the beginning. It has to continue through the whole process. Maintaining that discussion, especially in highly contested environments, is really what determines whether our project will have long term success.

Gwen: I read this book over the summer– it was called In The Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado, and it was really wonderful. It’s a memoir and she is recalling traumatic experiences that she had in her past, and she’s using the house as a metaphor for her body. The way it’s written is fragmented, and disjointed, and uses the spectrum of themes I’m interested in– like domestic spaces, privacy, and power dynamics. And that led me down this rabbit hole of researching the home, and building as storytelling. What are your thoughts on the art of storytelling through building a house?

Sergio: Well, you know, next quarter, there’s a big focus on housing in the curriculum. And that’s why I teach a housing studio. A home, or a house, is significant to every culture, right? ‘Cause it’s not only a functional element of a society and the building block of any community. But it’s also a memory and dream palace. It represents and connects all your dreams into a narrative. We’ve done a lot of Native American housing for different tribes. American tribes have been displaced from their traditional way, so we had to bring back decent housing back in the central states of Dakotas and Montana and Washington– the Yakama, the Cheyenne.

And we started out by just having them begin to map the different things in the home. You know, where and in which ways are their cultural values normally mapped in a house. Like the Native Americans in Alaska, they have a room which includes all the mementos, and it has to be the first space– It’s almost like an archive. So in the beginning, it’s almost like the storytelling is wound around the different ways that the family is construed, and the different ways that the people who inhabit it relate to each other and relate to the community at large. And then we think of the building–we try to take people through this exercise of talking about what their relationships are like. How do both the familial and the the community and all of these kinds of relationships begin–it is a series of stories. And you look at how all of these things relate to each other. A home is actually maybe the most complex construct that there is because it involves all the layers of a society– From the individual to the society. And because in the end, your house is part of a community, so it constructs both the individual story, and the collective narrative.

You know, once in a while somebody gets it just right, and you go, oh, that’s fantastic. And sometimes the best description of a house is not a beautiful rendering, but it might be a story that talks about what happened in that house, or how the family interacted with each other in the space of this shared, collective construct. Even in design, sometimes writing becomes more important than drawing. And then sometimes a filmic vision becomes important. If we’re designing this right here– this is actually part of the Alaska tundra that’s melting. And so there’s a village here. If I’m designing a building here, I’ll have the students begin to make a film that starts here and determine what might be three different filmic moments about what your home is like. You’ll write the storyline of the film. For a film, every page in a storyboard tells you a lot of significant things. Not only does it tell you what’s happening, but it tells you what the mood is. Is it dark? Is there a sense of connection? Do you feel connected to the houses? Do people have porches? Can you see them? And so every frame of that is establishing a story in itself. And so if my house is here, I ask the students, include yourself in three film walkthroughs and tell me the story of your house. And to do that, you start to tell the story of these houses and how they relate to the street and what the nature of the street is. And when you get there, how does the street continue? And what’s different about it? And who is the character? Now your house is part, but only part, of the community’s narrative. So yeah, there are many ways to think of a house because a house is like a Lego piece, which belongs to all the puzzles.

Gwen: I also love what you said about the house being a site of memory, of dwelling, of dreaming. These are themes I’m really interested in.

Sergio: And, and the other thing is that it’s dynamic, right? So you want to build something that is dynamic enough so that in times of hardship for the community, and in times of affluence and success, it can play a role.

Gwen: Yeah. That’s interesting to think of how a house could adapt to community, or personal changes. And then I’m also thinking about, in storytelling through the home, who has the power to narrate the story? I think that’s the other aspect I’m thinking about in relation to socially engaged practices in architecture. It’s usually the “builder” that holds the narrative power.

I’ve been thinking about these themes in relation to my work, and my studio art processes, and I’m trying to think of ways to also create functionality and community spaces.

Sergio: I will tell you about the Gateway Pavilion, this giant chrysalis we created, that looks something like your pieces. The Gateway Park area is ethnically the most diverse part of Portland. It is home to Russian communities that came here in the fifties, and there are also around 200 Somalian families living there. We had like eight different translators come in, and that’s why people were voting with Origamis. When the design process ended, they were talking to each other after never speaking before– they asked us what happens next? They wanted to continue working on the process, even though it was done. So we came up with this beautiful idea. We folded all of the origami paper that had fertilizer on it, and we put seeds for plants. They planted seeds in a large part of the park, and that night we had a big music festival, and everyone got to take three origamis with little pots so that the plants will grow.

Professor Sergio Palleroni is a faculty member and director of the Center for Public Interest Design in the School of Architecture at Portland State University and co-founder of PSU’s Homelessness Research & Action Collaborative. He also serves as a Senior Fellow of the Institute for Sustainable Solutions and is a founding member and faculty of the federally funded Green Building Research Lab at Portland State University. Professor Palleroni received his M.S. in Architectural Studies from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Oregon. His research and fieldwork for the last two decades has been in the methods of integrating sustainable practices to improve the lives of underserved communities worldwide. In 1988, to serve the needs of these communities he founded an academic outreach program that would later become the BASIC Initiative (www.basicinitiative.org), a service-learning fieldwork program. Today, the BASIC Initiative continues to serve the poor in Asia, Latin America, Africa and the U.S. In addition, Professor Palleroni has worked and been a consultant on sustainable architecture and development in the developing world since the 1980s, for both not-for-profit agencies and governmental and international agencies such as UNESCO, World Bank, and the governments of China, Colombia, Costa Rica, India, Kenya, Mexico, Nicaragua and Taiwan.

Gwen is a visual and social practice artist who currently investigates the physicality of emotional experiences, and how those experiences live within the body waiting to be released. After receiving her bachelor’s degree in psychology, she worked as a social worker in the mental health, addiction, and cognitive health fields, and then received her MA in Drawing at Paris College of Art. Currently, as an Art and Social Practice MFA student at Portland State University, she use mediums of painting, drawing, photography, sound, and conversation to explore how we find stories within pieces, creases, breaks, and bends.

Stories & Melodies in the School in the Sky

Domenic Toliver in Conversation with Frank Cobb, Meta 4(Sadie), Duane (Casper) and Gwen Hoeffgen

“Truth is, we aren’t out to hurt you, you act like we’re hurting you when you’re really hurting us.’”

I’ve always believed the best moments in my work happen when I’m not trying to make anything at all, when people just start talking and the room shifts. This is just a piece of that from a day at Street Roots doing our weekly photography hangouts with Frank, Duane, Joan, Sadie and everyone drifting in and out. That day Gwen and I were there to help folks make photo books with photos taken in previous hangouts. The books quickly became secondary to the stories: a harmonica origin story no one will ever know the truth of, Spider-Man facts, bad puns and poetry. I chose this conversation because it captures exactly what I love about the work. The way people build meaning together without even noticing, the way laughter and memory and small disagreements become their own kind of art. The way they move through the workshop, joking, disagreeing, teaching each other, improvising, it all reflects the knowledge they carry with them. It reminds me why I keep showing up: not just for the photos, but for the people who bring them to life, and quite frankly that’s it.

Interlude: Spur of the moment– Frank whipped out a harmonica from his jacket pocket, a childish smirk on his face, he shut his eyes tight and began to play. For all I know he played an original tune, not as easy as Roadhouse Blues but a simple melody that froze the room. What follows is a snippet of that afternoon, unedited, a little messy, and exactly what it felt like.

Frank: (harmonica)

Gwen: Wow!

Dom: Oh wait, you gotta do one more riff. I have to take a picture.

Frank: (harmonica, same tune)

Dom: You’re really good, how’d you learn to play?

Duane: Yeah yeah, it’s only because I taught him how to play it.

Frank: Tell them the real story of how that shit happened, man. Just keep it real. We were down at the –

Duane: We were down at City Hall. We were doing a camp out at City Hall. And I broke out my harmonica and started playing, and he was like, “Man, I’d like to learn how to play like that.” So I told him I’d teach him, make him a pro… What? Say it didn’t happen like that?

Frank: That’s so bullshit. The first time I ever picked up a harmonica, ever-

Duane: Was at City Hall!

Frank: It was at City Hall, I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing and-

Duane: I know and I taught you how to play!

Frank: I wanted to play and so I just started fucking playing, I just tried and it sounded like that. Just started playing like this right off the bat. Really, and I didn’t think it sounded good at all.

Dom: What?

Gwen: Really?

Frank: I kid you not, I thought I sounded stupid.

Gwen: That’s actually unbelievable!

Frank: I thought I sounded so stupid. I really did, I was like “Oh I’m done with this, it’s bad. I’m usually good at everything.”

Dom: Were they telling you that you were good?

Frank: Everyone kept trying to tell me, “You sound great, you sound amazing!” Even this guy *points to Duane*

He kept telling me to play. I was like, “Ehh nah I’m not good at it.”

Dom: So he just picked it up and started playing like that, that’s impressive.

Duane: He’s such a liar. Bullshit. He knows I taught him how to play.

Frank: I’m not making it up, you going to beat me up with your strong hand? Look out baby, hold me back.

Duane: He just doesn’t want to give up our secrets, I taught him.

Frank: That was a while ago. I’ve known you longer than I’ve been working at Street Roots, Duane. That’s crazy. Since fucking greenhouse.

Duane: I know. That’s insanity. And as long as you tried to get me to work here with you. You did try for almost twenty years!

Frank: Yeah. Damn. I would tell him every day: “Come on dude, just come work.” And he’d be like, “Nah, next time”

Duane: All it took was the right look, and you didn’t have it, Frank.

Dom: Ouch.

Sadie: Are we supposed to be working on our covers?

Gwen: You guys could do your cover or write in your books, it’s up to you.

Sadie: I think I want to do my cover with no binding.

Gwen: Oh you want to keep it how it is, we can hole punch it and tie it with string?

Sadie: I like that. Let’s do that.

Gwen: Okay, so I can do two holes on the side. And then you can choose a string and tie it together. I did it like this, I folded these two over, and then cut it barely, and then you have to get the double-sided tape right on the edge.

Frank: That looks cool.

Dom: It could look cool if you decorate both sides too.

Sadie: I want to make sure I get it right in my book, I suffer from not paying attention sometimes, your names are Gwen and Dom right?

Frank: Yeah Gwen and Dom, Gwen like Spider-Man.

Gwen: Yup.

Frank: Are you a Spider-Man fan? Gwen Stacy. Is a Spider-Man character.

Dom: Oh yeah, she is a Spider-Man character.

Frank: That’s how I remember the name Gwen, Gwen Stacy from Spider-man, maybe that’ll help.

Gwen: Or like Gwen Stefani.

Sadie: Gwen Stefani, yeah. I like that more. I’m like— Gwen Stacy? I’ve never heard of this person.

Frank: You’re like “Who the fuck is Gwen Stacy?” I guess I’m a—I’m a nerd. Yeah, I’m a nerd. But how do y’all not know Gwen Stacy. She was Spider-Man’s first love. Before what’s her name?

Gwen: Mary-Jane?

Frank: Yes, Mary-Jane

Dom: Isn’t Gwen Stacy the one that fell?

Frank: Ahh yeah she did.

Gwen: Wait, what happened to her?

Dom: You never read the story or seen the movie?

Gwen: No.

Frank: His first love and she knows he’s Spider-Man. She’s always caught in the middle of his fights. Okay, so one time, she falls from a building. Snaps her neck or something, or hits her head.

Dom: He saves her almost though right?

Frank: He almost does. His web reaches her, but she still dies.

Sadie: She should’ve aimed for the bushes.

Frank: Wow, shut up (laughs)

Duane: Am I able to put some poetry in this. I have a poem but I can’t write it.

Gwen: Yes of course, I can maybe write it in there for you.

Duane: Okay, record this.

Dom: It’s still recording.

Duane: So we’re talking about the experience of the poor and the rich. As I’m asking them if they want to buy a paper so we can support ourselves and feed ourselves, they don’t realize we’re the working class just like them. They look at us like we’re nothing, they walk around us scared to death of what we’re not going to do to them. It doesn’t hurt me like it hurts others because I’ve experienced so much of it in my life, being poor and homeless and in need a lot of the time. Broken, walking, or so. Truth is, we aren’t out to hurt you, you act like we’re hurting you when you’re really hurting us.

Gwen: That was good, yeah I can write that in your book.

Duane: Could you also do five covers for my books? I got five poetry books.

Gwen: I can’t today just ’cause we’re not gonna have time. But maybe next week we can start on that project?

Duane: Wait, oh I gotta go. What time is it?

Gwen: It’s 1:10.

Duane: Oh, I’m late.

Gwen: You’re late? Okay. Come back next week and hopefully we will have your photos by then. Fingers crossed.

Duane: Okay. You said it’s 1:08? Oh man, I’m late. Oh, Frank’s fault again.

Frank: It’s always Frank’s fault.

Duane: Yeah, just like Frank. Making me late. It’s okay. Frankly, frankly.

Frank: Frankly— frankly it’s okay.

Dom: Be frank he has to go, Frank.

Duane: Oh just Frank saying, Frankly saying Frank. Can I be frank with you right now, Frank?

Is that a frank hotdog?

Gwen: A frank dog?

Duane: Just wanna be frank with you right now.

Sadie: Lets stop.

Gwen: Yes please.

Dom: Oh I got a feeling you’re late everywhere you go, Duane.

Duane: Hi, you can call me Late

Gwen: Bye Duane. Have a good week.

Duane: I will. Bye.

Domenic Toliver is an interdisciplinary artist and educator working across film, photography, performance, and socially engaged art. His practice emerges through dialogue, where responding to people, what’s said and unsaid, becomes a creative act in itself. He approaches his work as an ongoing process of questioning rather than seeking fixed answers, embracing change as both material and method. For him, life itself is a form of art—fluid, participatory, and relational.

Frank, Sadie, and Duane are Street Roots vendors and Artists that frequent a weekly photography/art workshop to collaborate with my partner Gwen Hoeffgen and I at the Streets Roots. Their works span poetry, photography, performance, drawing, and much more. Their photos and stories were presented and exhibited at Blue Sky Gallery for the December 2025 Community art wall showcase.

Gwen Hoeffgen is a visual and social practice artist who currently investigates the physicality of emotional experiences, and how those experiences live within the body waiting to be released. After receiving her bachelor’s degree in psychology, she worked as a social worker in the mental health, addiction, and cognitive health fields, and then received her MA in Drawing at Paris College of Art. Currently, as an Art and Social Practice MFA student at Portland State University, she use mediums of painting, drawing, photography, sound, and conversation to explore how we find stories within pieces, creases, breaks, and bends.

Feeling Very Vietnamese Tonight

Text by Sarah Ngọc Lưu with Sean Xuân Hiếu Nguyễn

“I just remember walking into a restaurant and seeing that as one of their beverage options, and was like, ‘Wait, are we drinking this?’ I was gagged.” 𑁋Sean Nguyễn

Sean and I first met through Interact, a high-school service club sponsored by Rotary International. Even though we lived in different cities, we became good friends as we regularly crossed paths since our high schools fell under the same 5150 district. Over the years, we graduated, went to college, and took off to start our lives. We first reconnected after running into each other at a HorsegiirL show in San Francisco over a year ago. My best friend, Alan, bumped into his ex-roommate on the floor who just so happened to be Sean’s partner (which I had no clue). When Alan and Sean’s partner saw each other, they screamed. When Sean and I recognized each other, we screamed. And then the four of us screamed together.

After such a fateful night at the club, we followed up with each other, discovering our shared love for a documentary about the Vietnamese-American New Wave scene and realizing two things: we were both pursuing graduate degrees and our themes of research were incredibly similar. With our curiosities aligned, we spent some time chatting over the phone. Reflecting on our thoughts and shared experiences, we reimagined alternative ways our collective histories can be remembered and how our legacy can transgress inherited traumas.

Sean Nguyễn: I think the last time that we talked, there were a whole slew of combinations that just made me feel like I wasn’t stable in my research. Where I am now is still slightly unclear, but I’ve moved myself into a more interdisciplinary approach. I’m trying to think about Vietnamese American storytelling in this particular way where we’re departing from the Vietnamese American literary canon that has been set up by authors like Việt Thanh Nguyễn and Ocean Vương.

These people who were making that be their work were being produced in some type of accommodationist white market. I think particularly why the Ocean Vương books did so successfully was because it really allowed white people to self-flagellate themselves and induce white guilt.

Sarah Lưu: How so?

Sean: I think now we’ve surpassed this really interesting period between 2018 and 2021 of just like pure unadulterated wokeness. I’m wondering how we move on from here where there’s movement outside of identity politics into something more critical?

Sarah: Is there anything you might be looking into that you feel brings a more critical sense beyond identity politics?

Sean: I just finished this book called Mỹ Documents by Kevin Nguyễn. The way that it’s written borrows from the history of Japanese American incarceration camps. Basically it’s about a series of terrorist attacks in the United States, seven bombings in different airports. The assailants are Vietnamese, and that triggers an executive order that puts all Vietnamese Americans into mass detention.

It’s in the perspective of these four half siblings. Because their father left several families, he now just has this cohort of half siblings and they kind of know each other. So he reinvents another set of contemporary displacement to think and exercise how we might reexamine Vietnamese American trauma, how we endure it, and how we could resist it without necessarily having to reinvoke the Vietnamese American refugee narrative.

Sarah: Which in many ways, is what we’re both thinking about now, too. We’re just both wondering what our “how” is.

And I definitely agree about those works appealing to a white audience in some ways. My first impression of Ocean Vương’s work was that it was beautifully written from a Vietnamese experience, but it didn’t particularly feel like it was for a Vietnamese audience. It didn’t feel like it was written for me.

Sean: I’ve been thinking, there’s a significance of family archives in Vietnamese American storytelling. Oftentimes family archives or family histories are the loci of how a Vietnamese American writer would want to approach storytelling, even if not for it being the main part of the story. It’s how one gets findings and the research to start writing.

There’s this idea of the second-generation Vietnamese American storyteller whose writings are incredibly distinct from that of the 1.5 generation* who hold direct experience of the war and can recall their own personal memories and/or the lack of it. Second-generation writers have it a bit more complex because they have to draw from different sources, but also hold a responsibility to acknowledge the distance between generations and their disconnection from the war.

*1.5 Generation: Those who were born in Vietnam but immigrated to the U.S. as children due to the American War.

Sarah: How does this responsibility affect the way we evolve? What are some of the implications it might have on how the second generation sees itself?

Sean: Hmm. Maybe responsibility isn’t the right word because I feel it makes it sound like a burden that we haven’t experienced the war, but it does complicate our identities in the way that our direct history has to do with state-sanctioned trauma. It’s more of asking ourselves, “How do we continue to acknowledge and critique the war without having to always resurface the terrible?”

Sarah: Which is literally what I’ve been asking myself in my own research. As a child, anytime I wanted to learn something about our people’s history in America, I would see our people subjected to pain. They’re hiding, running, or lifeless. They’re in tears, faces filled with fear, desperation and uncertainty. I always felt like there could be more beyond the suffering. Wanting to know more about our ancestors’ history in the land we were born in just shouldn’t solely lead others like myself to the terrible and graphic.

Sean: I would love to point you in a theoretical direction. It really helped me think differently about my own thesis. What you’re talking about is so resonant with a concept I read about by Ly Thuy Nguyen called “Queer Dis/inheritance” where she essentially completely rejects the inheritance of her family’s trauma.

Sarah: Wait… I’ve never even thought about that at all. To me, it was always a part of us.

Sean: There’s talk about this sort of silence, one that’s provoked or even intentional between us and the 1.5 generation. There’s this Vietnamese-American artist, Trinh Mai, who made an installation called, “We Should Be Heirs”, where she displays unopened letters from her grandma. The unopened letter represents that collective silence and that takes shape in many ways. Keeping these letters unopened, holding her grandma’s secrets, tends to the gendered violences from the Vietnam war, like the way masculinity in the community has been handled differently in the refugee narrative.

Sarah: How does addressing the silence by leaning into it change the way we think about these gaps of silence, intentional or not, between generations?

Sean: Well, part of the ethos in Trinh Mai’s installation is that there is a contextual gap between her and the viewer, who maybe doesn’t know much about the Vietnam War. She’s not trying to set her work up as an educational activity, but rather just wanting to address the silence that’s between her and her grandma. In doing so, she recognizes her grandmother’s dignity that had been soiled in the process of displacement, being displaced, and then being racialized in the United States. I think that is a really generous and critical understanding of how we can think about the gap between us and the 1.5 generation, or the first generation, maybe.

Sarah: Wow. I love that approach. And I’m well familiar with Trinh Mai! I was able to hear her speak about her practice at an art lecture during my undergrad and she was the first artist whose work made me cry. That unintentional/intentional silence on war experiences is something I actually didn’t experience much of. My mother was very vocal about my family’s experiences, and was always sharing the photographs she had brought with her on boat. It’s led me to think constantly about others that might’ve done the same, and so I’m curious what you think. How does a family’s archive change when it crosses an ocean?

Sean: Wow… hmm. The crossing of oceans gives us an element in which the archive had been produced haphazardly, a byproduct of this really large imperial violent activity. If we were to think about your family’s collection of photographs being collected within the sense of urgency, then that already gives it so much more meaning.

I was TA-ing for a class yesterday, and we’re talking about this author named Karen Tei Yamashita, and she is this really awesome Japanese American writer. In one of her talks, she was addressing the question, “What does a home for Asian Americans look like?” She talks about this home as an imagined condition, represented by the crossing of oceans. That transnational part cannot be missed about how we think about archives, migration, and movement over the water.

Sarah: I completely agree. Our archives are so special because there are roots planted in multiple points around the world. And maybe that affects how our families have chosen to plant their roots here in the states. I imagine that every Vietnamese immigrant household is a reflection of the places they’ve been. The things that are collected, repaired and treasured… that in itself is an archive of its own . It’s a shame that many second-generation folks only describe it as “hoarding”. I feel like there’s much more to that. What do you think?

Sean: Well, the hoarding is like a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder for sure. When I think of hoarding in our community, I think about how displacement has conditioned lots of Vietnamese refugees to collect. It really can go both ways where if you lose your home first, you might be conditioned to think that nothing of yours is ever going to be permanent again. Conversely, if you were to lose your home in a very serious way, you might be conditioned to believe that you should build your nest with anything you can keep your hands on to affirm yourself that your home is here, represented by these objects. The sense of permanence is represented by how much stuff you have in your home.

Sarah: This idea of accumulating as many things as you can to make sure that it’s permanent…That kind of parallels these personal family archives that traveled across the sea. How many things can I accumulate in my go bag? What can I take with me to preserve these memories I have of home? What is most important about the life we are forced to leave behind?

Sean: I think also another important element of these archives is, how do these objects tell a story when they’re all put in context with each other?

Sarah: That New Wave book is a great example to answer that question. I mean, when I shared that book with my aunts for the first time they screamed when they skimmed the pages. If those stories and photos were shared separately and not in that sort of “New Wave” container, they might’ve not associated it with New Wave music, but just a reflection of life for them in the 80s. But together, they saw a community carved out for themselves by themselves, clinging onto music to heal.

Sean: Which is why I think it’s so special because it has a postcustodial, living archive element when you think about it in a kind of meta way. It already has a really different perspective about the Vietnamese American lived experience through the practice of its archival research being sourced from different families across the states and all across the global diaspora. Collecting photos from several diasporas broadens the scope of it, and orienting its touring theater screenings within our community ties it all together as something that is living and breathing. It isn’t just static in its presentation or as something to be watched, but something to be handled.

Sarah: Definitely, oh my gosh. The first time I went to watch it was through the CAAM Festival at SFMOMA last May. I brought my mom because the Ruth Asawa show was happening at the same time. We saw the book first and thought it was going to be on the more lighthearted side, with all the glitz and glamour. When we left the screening room, our faces were wet and puffed red. During our CalTrain ride back home, we just talked the entire hour and a half. My mom was bringing up new stories I had never heard before. To see a documentary have so much reactionary power, I was in awe. It was deeply activating our personal repositories of memories.

Sean: Exactly, and the documentary wasn’t pulling things that we were never aware of. The things that were discussed were things we grew up watching, too. The documentary generates this drive to inquire critically about your heritage. The reason why we didn’t inquire about it is because we never understood it in the form of a story before. Otherwise, it would’ve been a pretty conventional and unassuming part of our lives, just something that our parents used to listen to. Because of Elizabeth Ai being able to turn it into a story, something to be moved by, it allows us to think more critically about our own history.

Sarah: I’ve been asking myself that, like what’s my story? What’s this narrative that my research could uncover? Elizabeth found a story in our relationship to music. I’ve been exploring our culture’s food and cooking.

Sean: Have you ever seen your mom make thịt kho? The caramelized meat and eggs?

Sarah: Yes!

Sean: Does she use the coconut drink*?

Sarah: Yes, she does.

*Ahh yes…the coconut drink. Coco Rico soda might just be a nice carbonated beverage to you, but to many Vietnamese immigrants, it’s solely for cooking, and the key ingredient to making your meat tender for thịt kho.

Sean: She does! Okay, because recently I went to this restaurant in San Francisco called Parada 22 and they sell the drink, you know, to drink. I was so taken aback by it because I’ve never questioned its ability to be… drunk. I just always thought it was a cooking ingredient because that’s only how I ever saw it.

Sarah: Me too! My mom would have so many of those coconut soda cans stacked underneath our kitchen table.

Sean: Exactly, it was just like MSG or nước mắm––another cooking ingredient. But anyway, I just remember walking into a restaurant and seeing that as one of their beverage options and was like, “Wait, are we drinking this?” I was gagged. How did that come to be? Has it always been a tradition?

It makes me think, if we were to assume that it isn’t a traditional thing and that it might’ve come from the sorting of resources for our moms to be thinking about that ingredient in the same way.

Sarah: Maybe there was a network of recipe exchanging that we might’ve been unaware of.

Sean: Those recipes must have been orated in a way where they were passed through communities through word-of-mouth. I don’t know that I’ve ever really seen our recipes being written down. That’s never something my mom did, and if she did, it was really rare. Maybe for stuff like banana bread, you know?

Sarah: Yeah, my mom was the same way. I remember asking her how she learned to cook and if there were recipes my grandma shared with her. She told me there were no recipes, just my grandma. Nothing was written down, it was all recollected in memory, passed down from one matriarch to another. I’[m always wondering which of those memories are the oldest.

Sean: When I think about the passing of family recipes, I think a lot about what dictates a mother to make the decision to teach those to their children. For my mom, she’s been particularly hesitant to hand them over because I believe there’s a certain part of her that thinks she can still cook for me. There’s a bit of a power resistance going on where the passing down of recipes to me will lead to a lessened reliance on my mother to make them for me. It’s almost like, if I were to ask her for a recipe, she’d be like, “Okay, so you’d rather I die.”

Sarah: Okay, your mom is hilarious. Love her. But it’s quite interesting isn’t it? My mom isn’t really the same way, but she’s a heavy criticizer. Both of us are huge foodies and we love going out to eat. Whether it’s a new trendy spot or the tried-and-true phở restaurant close to home, she’ll always say at the end of the meal that she could 1000% make it better. And she knows exactly what ingredient it might be missing.

And again, I’ve asked her how she learned these skills and all of the recipes she’s cooked meals for me from. She said my grandma. There was no book to read or notes to take. My grandma would just be with her in the kitchen telling her what to do until my mom remembered it all by memory.

Sean: These unspoken customs make me think to put it in a larger context. We have a certain responsibility when we’re researching critical refugee studies and diaspora studies. How do we discern a Vietnamese American diasporic tradition that maybe would distinguish themselves from other communities who have been affected by displacement? What is the Vietnamese American response? What were the conditions that allowed us to think about things in a particular way than how a Chinese American or Mexican American would approach these questions of passing down family recipes or engaging in their own archives?

Sarah: I had a really great discussion with my directed studies advisor, Dr. Kiara Hill, whose work is rooted in the African diaspora. I was feeling lost with where to even start with such a grand topic, and she told me, “The seeds are in the mundane.” Thinking specifically about that, the simple ways we wake up, share meals, rest, work, and play… Observing our day-to-day habits could hold potential to show us what the Vietnamese experience is.

Sean: And resistance, especially when we’re thinking about the maintenance of memories; there’s a practice of certain memories we choose to keep and throw away for the sake of self-preservation. Something that you might benefit from is looking at Marianne Hirsch’s The Generation of Postmemory. She poses a lot of the questions we’ve been thinking about, which is how do we keep refugee traditions or practices in our memory without having to retell the horrors when it’s not necessary? Are we bringing up something that we don’t want to? What are the conditions of the baggage that comes up whenever we talk about the Vietnam War? Even though she’s writing it from a Holocaust perspective, the same mechanism of recalling memories from war, violence, and genocide are one and the same.

Sarah: The maintenance of memory sounds very alive. So what if memories are all that makes an archive? Could a person exist to be an archive in their own body? Memories stay as long as they live in others and I’m intrigued by the idea that an archive has a living heartbeat. When I think about archives, I think cream boxes on dusty shelves. I don’t want that to be how our histories are preserved and that being our legacy.

Sean: We’re kind of trapped in time with how we’re represented at the moment. Even so, writers like Việt Thanh Nguyễn and Ocean Vương are quite responsible for really breaking the Vietnamese American stories into the general market for refugee storytelling, so when they tell their perspectives as refugees, it’s really what they know best and what’s most earnest to them. But that being reiterated is somewhat of a problem too.

Sarah: It is definitely possible to have a revisitation of the trauma in a way that isn’t reimagining the experience and expanding the pain.

Something I’m curious about is the disconnect between us (Việt Kiều*) and the Vietnamese people back home. I’ve never been to Vietnam, but I hear that how we think of the war and the way it circulates in conversation is different. I wonder if that also applies to the way they address their war-related trauma, too.

*Việt Kiều: Term for describing those of Vietnamese descent living abroad.

Sean: Oh yeah, absolutely. When we think about how the Vietnam War was such an epic event in the American historical canon of empire, it was a huge ordeal… this holy interventionist thing. And then the whole humanitarian part of it is such an ingrained part of our American history. But in Vietnam, it’s one of many in their many years of colonial history; they treat it almost as if it was a footnote. Their entire history is predated on colonization, so in some ways colonization is part of their national identity and sense of nationalism.

Sarah: How did you learn about that?

Sean: It was expressed to me when I went to Vietnam earlier this year. I stopped by this risograph studio in Ho Chi Minh City called “We Do Good”, mostly because I wanted to take a look. But I was picking their brain a little bit about Vietnamese history and how Vietnamese youth are thinking about these things.

They deal with a lot of censorship and there’s a lot of criticism about the government, but not a lot is done or said about it. It’s just a conversational practice. For Vietnamese youth, they’re very apolitical about everything. When I asked them about what they’re making art about, it’s all about the personal, individual, and the family. Almost nothing has to do with politics. Bringing that into a larger context of history that isn’t visible, it was really hard for them to gain political support in expressing solidarity through encampments or protests because it wasn’t embedded in their culture or tradition to protest. It was hard to get word across.

Sarah: Which is a huge 180 from what we observe here, even with some in our immediate circles. I mean families will argue over which is the “right” flag, but it just ends at the dinner table.

Sean: Yeah, and it’s interesting how much Vietnamese youth are gravitating towards the art scene. It’s all an archive in its own way.

Sarah: Making art about their day-to-day life…if we put all of those works into the same container then in some ways it’s a capsule of the Vietnam our parents never got to know. The way our parents might experience the expressions of this unknown Vietnam to them may be a parallel to the way we experience these memories of war from a secondary perspective.

Taking everything we’ve discussed in account, how has your research journey impacted the way you are thinking about the Vietnamese-American experience? How did your findings and field research in Vietnam help you further understand our place here?

Sean: I realized that the site of our inspiration and the passion is driven by one’s self-reflexiveness and own sense of urgency for wanting to learn about these things. I think it also affects the degree of critical consciousness. A lot of people our age are stuck at discovering one’s own identities through the way that we’re commercially understood or racialized. These master narratives have led us to believe that our culture is alive only through food and tradition as we know it.

I think the stuff they do at Vietnamese Student Associations, with these traditional dances, for instance, is how those patterns and practices are reiterated and are oftentimes a comfort zone for a lot of Vietnamese Americans. While it’s really great to celebrate our heritage through traditional dances or these grand cultural shows, it’s an echo chamber. These commercialized things become the responsibilities of burden, because we have it in our imagination. We were raised to think about how hard our parents have worked for us.

When we connect our reading and American heritage to large complexities of capitalism and imperialism, we become unburdened as our experience as a Vietnamese American becomes something greater than the family. If we have no tactile relationship with literature, we are missing the chance for our brains to reimagine how the conditions for our world can be. Refusal to read types of literature and diaspora storytelling outside of our cultures restricts empathetic capacity for other diasporas.

Sarah: How would you reimagine it all for yourself?

Sean: I want to feel some type of ancestral soil, to understand ancestry beyond grandparents, to have a developed home. A better imagined world is one where home is a bit more definitive and stable.

SEAN XUÂN HIẾU NGUYỄN (he/they) is a master’s student in Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University. They received their Bachelor of Arts in Ethnic Studies at UC Santa Cruz. Sean is a multidisciplinary writer and aspiring educator, and their developing research examines Vietnamese American narrative strategies across literature and visual art via personal family archives. They currently work with the San Francisco State 1968-69 BSU/TWLF Strike Digital Oral History Archive. Nguyễn likes Tuesday crosswords, portmanteaus, and audio guides at the museum; he does not like slow walkers, double negatives, and dogs in restaurants.

SARAH NGỌC LƯU (she/they) is an interdisciplinary artist and writer. She gravitates towards photography, ceramics, zines, print-making and music. Her current interest revolves around the experiences of the Vietnamese diaspora and how its complexities are largely preserved through memory. Lưu’s work has touched on themes of their mixed Vietnamese-Chinese identity, intergenerational trauma and cultural traditions. She explores themes outside those topics by grabbing inspiration from her lived experience growing up in the Bay Area surrounded by a vibrant arts and music culture. Lưu holds a BA in Studio Art, Preparation for Teaching from San Jose State University and is currently studying for an MFA in the Art and Social Practice program at Portland State University. Her favorite food is her grandmother’s Bánh Canh and she can roller skate backwards.

Seedling Stories

Adela with Wendy Shih

“For me, sharing books and stories with people is what matters. I am trying to increase access to them because I want to spark that connection between the person and the book, but also between people, with the book as a catalyst. It’s powerful because every single one of us has a role to play in creating this web of interconnectedness.” – Wendy Shih

I met Wendy (施文莉) walking at a Pride Event called Gays Eating the Rich in the Park. I was instantly drawn to her space because the books she had displayed in her Diverse Free Library swap were entirely by disabled, BIPOC, queer authors.

Growing up as an autistic, queer kid in Colombia, I did not see myself in any of the stories that I read. Even the ones where weirdos banded together against “evil” had racist undertones.

Later on, as a Literature major, I realized that even our curriculum was plagued by the European-white canon: I only had one indigenous literature class, a few on Latin American literature, and one on colonial literature. These, however, were invaluable, as they led me to question the negative space: who is not being shown, why not, and if they are (marginally), how are they represented?

This is what drew me to Wendy’s stand that day at the park. As someone who also believes in the power of stories, her decolonial Free Library felt like a usage of that negative space to bring forth the voices of our people of the Global Majority, which the system has been trying to erase.

Here we talk about being atravesadas, people that belong nowhere and everywhere, and our hope that stories can be a seed for connection and action.