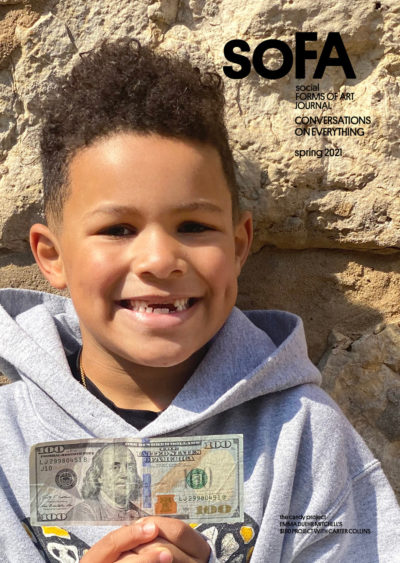

Conversations On Everything: Interviews Spring 2021

Editor’s Note: The Source Commissioner Speaks

“I personally believe that someone can make amazing work for $100. And somebody can make horrible work for a million dollars. And every possible thing in between.”

– Harrell Fletcher

In Spring 2021, Portland State University Art & Social Practice MFA students were each given $100 to commission someone to do something, anything. Projects created include: buying candy for an entire elementary school; continuing an AGNES VARDA FOREVER poster project; retroactively compensating for a minute of building Black excellence; taking a nostalgic driving tour around Bed Stuy, Brooklyn; paying an anonymous woman surfer to go surfing for a week.

For this issue of Conversations on Everything: Social Forms of Art Journal, MFA students interview those they commissioned. They get to know each other more, plan their projects, and discuss meanings of art and labor. In place of an editor’s note, Salty Xi Jie Ng interviews program director Harrell Fletcher, who commissioned the commissions. He talks about this unusual class assignment, its multiplier effect, shared authorship, the creativity that can emerge from limited resources, and how a fixed multiplayer framework facilitates the appreciation of diverse expression.

Salty Xi Jie Ng: How did you come up with this assignment?

Harrell Fletcher: I was trying to figure out a real world project that could happen within the program, that gave everybody the chance to try out what it was like to do a few different things. One of them was the idea that instead of using money that comes to you, you could transfer it to somebody else. And that goes along with this concept of repositioning, an approach that I’ve used in my own work, but I didn’t really have a framework for thinking about it. This idea of repositioning is where, as an artist, you’re given platforms, resources, or opportunities, and you can choose to allow somebody else to use that opportunity, resource, or platform, but to do that as your work. You’re not doing it in an altruistic way; instead, you’re sort of doubling the resource—I get something out of it as the artist, but also somebody else who may not normally have this kind of opportunity would now get it as well.

Anyway, I was thinking about those kinds of things and trying to figure out how I could make an object lesson circumstance where everybody in the program would get to work through this framework with a relatively small budget, one that needed to cross the threshold where it still seemed like something. $100 is becoming less and less all the time, but it still means something in our imagination. It depends on the context and who’s receiving it. And that was something I wanted the students to think about too—who makes the most sense to commission for this amount, this particular budget.

So the assignment provided an opportunity to think about a whole bunch of different aspects that come into play with social practice: crediting people; resource sharing; repositioning; the idea that as an artist, sometimes you can curate, commission or edit—you can use other modes that are oftentimes seen as a background role, but you can forefront that role as your own work. I was thinking about all these different things jumbled up together. It seemed like it might be an interesting experiment.

Salty: What was the process like? Did the students discuss with you what they were going to do and did you give them any feedback?

Harrell: I gave them an outline, which was that it needs to be framed as a commission, and the $100 should be the total amount that’s needed. You can add on to the project later if you like. It shouldn’t be like, Here’s $100, for really what should be a $1,000 project. Part of what I am trying to think about too, is that, when people get commissioned to do a project in general, or with a project budget of any kind, there’s going to be a set amount of money, whether it’s $1,000, $10,000, $100,000. I want people to be able to practice thinking within that budget limitation, because you’re going to ruin yourself if you can’t figure out how to modulate projects to fit within the resources that are offered for them. These could be monetary resources, space limitation, time, any of these things. Whatever the resource limitations are, you have to think within them.

The other requirements were that it had to be done by the end of the school year, and you had to conduct this interview that goes along with it. I talked to people individually about their ideas. Becca (Kauffman) was the very first person who was ready for the $100, so I Venmo-ed her the $100. I said to everyone, all you have to do is tell me what the project is, we’ll go through the details of it, and then I’ll give you the $100. I met with each person a couple of different times. As a group, everybody shared their plans, and we worked out some kinks together. Some people wanted to just pay the person $100 to do the interview, but the way we came up with this, it’s like a two parter. There’s the commissioned project and then there’s the interview about the commissioned project. Some folks couldn’t quite figure out what a commission was, or thought it should come back to them, because they were going to end up doing some work on it anyway. But overall it was interesting to see all the different approaches people had.

Salty: Let’s talk about the different levels or roles here. You’re the source commissioner who’s commissioning the grad students. And so maybe we can call the grad students the commissioned commissioners, and the people they worked with the final commissioned. And by the time we get to the people experiencing the thing that was made, it would have gone on to the fourth level already. You could walk past someone on the street and not know that they were affected by your giving out of this $100. This to me is part of the beauty of this exercise. What are your thoughts on this multiplier effect?

Harrell: I like that. I think that’s really interesting. In general, that’s a good approach to resources in general—not just keeping them to yourself but thinking about how you can spread them out. There’s some project I did in the past that I’m trying to remember—I eventually met a stranger and they were telling me about the project as if it was something I didn’t know about. And I was like, Oh, yeah, that’s my project. It had gone through enough layers that this person had no idea I was sort of the source of the project. In some weird way, it came back around. I like when what starts the process going gets sort of lost, and then the project offshoots and involves many people. That’s one of the things that I’ve been interested in, creating projects in which there is multiple authorship.

Salty: So how do you think these $100 Projects should be credited, as individual projects and as a collective whole?

Harrell: I’ve sort of intentionally left this unresolved, partly because I wanted to see how it went. Having done this first version, maybe we’ll do this again and have a much better idea about what is happening. But I think this is an interesting question. Some students that I’ve talked to like the idea that in a way, it’s my project, and that they are a sub, a delegated member of a project that I’m sort of orchestrating. That is one way of thinking about it. And then other people probably want to have nothing to do with me, and want to think about it as just their project, for which some dude gave them $100 to use. I kind of like that people are sorting it out in different ways.

And as far as I’m concerned, if somebody were to decide to formalize it on their resume or on their website, and they want to credit me, and see it as a project they’re participating in that I’m the big author of, that’s fine with me. I’m totally happy to validate the idea that that’s what’s going on. If other people don’t want to credit me at all, and not even acknowledge that they’re part of a set of other people doing the same commissioning process, I’m okay with that also.

Like so many other projects that exist, I like that we can look at it from different perspectives, make choices about crediting, and there can be multiple authorship. And there’s no scarcity. We’re not fighting over who gets authorship and credit. Because we’re the ones determining that, we can spread out the authorship and credit as far and wide as we want. And it’s still potentially as beneficial to any one of us, as it would be if we had somehow treated it in a very proprietary way and been like, This is just mine. I don’t think there’s any great benefit to doing that. Mostly people are misled in trying to retain some kind of sole authorship of projects, believing that they get more that way or something like that. I think that in the end, they actually kind of get less by treating it that way.

Salty: When I was editing the conversations between the students and those they commissioned, it was really delightful to see the variety of ways everyone chose to use the $100. This delegated model created more ways of thinking about art. For some there was this element of wish fulfilment, for others, it was about memorialising something, or a chance to get to know someone better, or getting someone to continue a great project, or giving someone resources to dream up something new, especially for the children, for whom it was like a bestowing of power. Justin did a retrospective commission, and both him and Bri brought the value of labor into the fore. What are your thoughts on the spectrum of ways that it was done?

Harrell: To me that’s one of the interesting things about this delegated model. The way I think of that term is the idea that one person is coming up with a structure and within that, delegating out little structures to multiple people. When you put it back together, you have this bigger piece. I think that can be an interesting and also liberating approach for an artist. Some people would think that that was stifling, limiting, taking agency away from artists, that you were giving them a structure that was similar to multiple other people. But on the other hand, we’re always working with limitations and structures. And so this is being very transparent about that, and formalising it. As you’ve described and which happened in this case, with limitations you wind up having all of these different responses to it. In a way, the limitation is what allows you to see the diversity of approaches. As opposed to if we had just asked everybody to do their own work, we wouldn’t have the framework of comparison to then be able to see the wide variety of approaches to a single structure that are going on. So I guess for me, it’s a confirmation that this can be useful and that it doesn’t necessarily have to stifle creativity. It can instead stimulate individual creative ways of addressing the challenge or limitation that’s been given to them.

Salty: Oh, yeah, absolutely. I think it is an infinitely expansive exercise. Were there any projects that were particularly memorable to you? Or that you were really intrigued to see how they would progress?

Harrell: There were interesting, different developments that occurred. For instance, Laura’s project was the first one to be realised. And as a result, it was a nice example to have floating around as other people were figuring it out. Partly because it was a very simple project, making this AGNES VARDA FOREVER flyer with her friend JJ. It wasn’t like a heavy lift, and it was a response to something that JJ had already done. Something that I’m always trying to emphasise within the program is, if you make things public, as opposed to how we normally think of artists making work privately in a studio, things start to happen that are unexpected and opportunities start to present themselves.

And that’s what happened with Laura’s project: she puts up these flyers with her friend JJ. And pretty quickly, there’s lots of different people posting it on Instagram who don’t even know whose project this is; I keep running across them myself. The Hollywood Theatre in Portland becomes excited about it, because they like to show Agnes Varda. They track down Laura and JJ, and invite them to do an interview based on it as well as curate something, and they’re getting promotion from the Theatre. They got connected to Agnes Varda’s daughter and son. All sorts of different things occurred as a result of this fairly simple project that was made public.

Salty: Because $100 could print 550 AGNES VARDA FOREVER posters.

Harrell: And Laura has checked on Google searches and suddenly, in the United States, there’s more Google searches for Agnes Varda in Portland than anywhere else in the country. To me, that was a really great example project to have, to show that you could do something simple, easy, fun, and that it would also lead to all of these other things, these funny, interesting connections.

It’s been interesting talking to Kiara about her project with her cousin, Jordan. It’s been a good experience for Kiara to think about how she might work, how she could collaborate with somebody like Jordan. From a plan for making a project together, I think it has now expanded to a much broader set of things that she can do. You can start a small, simple project, and then it leads you to other projects. In Laura’s case, one version of that is happening which is more external. In this one, it’s more like realizing, Oh, here’s my nine-year-old cousin, I could do projects with him. Kiara’s working on a virtual exhibition with Jordan and shooting video together and things like that.

This idea that happened with Justin paying Herukhuti for one minute of his time is something that I’ve been thinking about—retroactive projects and valuing people for their time. On the one hand, we could say $100 is not very much money, especially for a knowledgeable adult professional. But if we change the increments of time that the person’s being paid for, so in his case, reducing the payment conceptually to one minute, then suddenly $100 seems like at least a reasonable amount of money for one minute of time, as opposed to $100 for all of his life’s work.

As the artist, there are different areas you have control over. Instead of feeling like you are stuck with reality as it’s been presented, you start to realize that you can change it; you can go back in time, you can shrink time, you can work with all of these things that become very empowering. Justin’s project gives us an example of how to work with areas that normally artists don’t think of themselves as having agency over. Instead of being like, I don’t have enough money, I can’t do it, we can say, Well, we’ll just shrink what the expectation is, you know?

Salty: He made a very tangible statement about labor. I’m also thinking about the range of people who ended up being the final commission people. How do you think that commissioning a nonartist changes the way they think about art, their involvement in art, and what art can be?

Harrell: I think that was an interesting opportunity. I was hoping at least some percentage of the students would be working with nonartists. I’ve always used this as an example to try to flip my own understanding—if, say, a dance choreographer came to me, and said, Hey, I like the way you move, will you be a part of my dance performance? And I’d be like, I’m not a dancer. They’d be like, That’s okay, you just have to come to these rehearsals, and then we’re performing it, and you just get to be a part of it. And I’ll be like, Hm, that sounds like fun, sure, I’ll do it.

I wouldn’t feel like this person is a choreographer and I’m not, and maybe I’m being taken advantage of. Instead, I would see it as them extending an opportunity to me, and in a way doing this repositioning for me, where I get to embody an experience that I wouldn’t normally have. And so I would be appreciative of that. I wouldn’t feel like I had to get paid, or have equal billing or something like that. I would just feel glad I got to have this interesting experience. This is hypothetical and I could imagine it happening with lots of other things too where somebody was, like, Oh, we really like the way you cook string beans, will you come to our restaurant and cook the string beans for a night or something? I’ll be like, Okay, I’ll give it a try. You know, I don’t expect it to be my profession. But I like to have the experience of it.

And so I was hoping that by framing it through an art lens with nonartists, they would have this moment of thinking of themselves as having this capacity to do art, even if that wasn’t their profession or identity. And partly what I thought would be interesting is the discussion about it, where you get to ask, Well, what do you think? Is this a problem? Is this fun? Is this stressful? It could be different for each person. And an interesting question to pose to someone could be like, If we were to look at this thing that you do, surfing, or whatever it is that you’re already doing, but we reframe it as an artwork, and you get paid for it—how would you feel about that? How does it change things for you? Is that positive? Would that be something you desire? Is that something that feels shameful or guilty? Which seems kind of like what happened with the person Bri commissioned. And then talking it through and, asking, Would it be a problem if you were being paid by a surf company to do this? Oh, it’s only a problem if you’re being paid to do it as art because artists shouldn’t be paid? Because you shouldn’t be paid to do things you like, or what is it? What’s coming up here? And how does it apply to other circumstances?

Salty: I think what this did was create at least 13 new conversations about what art is, and definitely many more, because the commissioned folks will be telling their family and friends, Hey, I just got paid $100 to do this, and those people might ask, How is that art? It adds more definitions of art in an expansive way. Would you do this project, again, with a different amount of money?

Harrell: Potentially, if I had access to other amounts of money. I have done things that I called re-granting, starting back quite a while ago. One of the first ones that I did, where I formally thought of it like that, was in 2005 when I got the Alpert Award. I was given something like $50,000, and as part of it, I decided I would re-grant a chunk of that money. I can’t even quite remember how much I ended up re-granting, maybe $15,000. And so I selected a bunch of artists, and I gave them little grants of $1,000 each. I didn’t have specific conditions about them commissioning anyone or anything, it was just like a grant to do their work.

Salty: Did they have to apply?

Harrell: No, it was like the MacArthur Genius Award. They didn’t know, it was out of the blue. They suddenly got the award, and it was called the Earthling Award.

Salty: So in a way you were being a curator, except when the curator does it, it’s part of the job. But when you do it, you get to claim it as an artistic action.

Harrell: Yeah. There have been other circumstances where I did that in different ways, like offered up chunks of money that I got. In the case of the $100 Projects, it was strictly out of my pocket. But this year, I did get part of the U.S. stimulus money, the check from the government. So I got some extra money that came in out of the blue, as was the case for millions of other people in the U.S. I thought, What do I want to do with this money? And this was one of the things I thought I could do with it. Next year, I might not be in the same boat. So I don’t know that I would repeat it exactly.

Salty: How do you think that it would be different if it was $10 instead of $100?

Harrell: I think you could do it with really any denomination. But you have to then reframe what you’re going to do with it. Like, in what circumstances does $10 seem valuable? And so I think that you have to recognise that because there is wealth inequality in the U.S. and in the world, the value of money is not constant. Any amount of money means different things to different people. If a person has millions of dollars, then $100 is not going to be very valuable. For a person with very little money, literally on the street with 15 bucks in their pocket, suddenly $100 will seem like a lot of money. When we think about children, they aren’t allowed to work, they don’t automatically have money. They may have an allowance, maybe their parents give them some money. But even if so, it’s usually in pretty small amounts, and even with that, it varies. But if you start with the idea that you’re working with a kid, then maybe $10 will seem like a reasonable amount to do a project with.

And similarly, there’s other kinds of circumstances in which $10 might seem like enough. For instance, if you said to someone, Okay, here’s $10, I’m going to commission you to buy something in this convenience store, and then we’re going to put whatever you happen to purchase in an exhibition, with a label we make. And so somebody goes in and buys a bag of potato chips and comes back out, and they’re like, Okay, I did it. I’ve even got seven bucks to spare. And you say, Well, you can keep that for your work, and we’re gonna install this bag of potato chips in the exhibition; can you tell me what you want on the label? With something like that, suddenly $10 would work again.

So it’s just really a matter of framing, and sort of resource matching, where you match the project to your resources. And so you have to figure out how you do the best possible match to create the best work, given whatever the resource happens to be? Which could be $10, $5, $1, or $100, $1000, $10,000. It can keep going in all these different directions and people can make amazing work. I personally believe that someone can make amazing work for $100. And somebody can make horrible work for a million dollars. And every possible thing in between.

Salty: It occurs to me, though, that the resource of $100, in this case, does not really include a fee for the labour of the commissioned commissioner, as in the student.

Harrell: Right. And that’s because in this case, it’s a school project, it’s an assignment. And normally, you wouldn’t get paid to do an assignment in school. If I had extra money, then maybe we would have made that part of it. And maybe that would have been interesting to say, Okay, you get $100 for yourself, and you get to commission $100. If it was a non school based project, then I think that would make more sense. But because it is within a school assignment, on the one hand, you could say, I’m being asked to do this additional labor. But our program is not just the classes or requirements that involve grades or credits. I sort of see it as much more inclusive—kind of everything that happens during the three years that’s attached to the program is part of your education. It’s a broader sort of view that’s not about just paperwork and grades, but more like an immersive cultural experience.

When students select someone for our weekly Conversation Series, they’re not paid to do that. In the real world, you might get paid to do that, if you were working as a programmer for an institution. In this case, it’s a chance to flex those muscles and sort of learn about what goes into inviting someone as a speaker. So it has to be understood within the educational context, in which case, the idea that the professor is giving money from their pocket is unusual to begin with, that’s not part of what normally occurs. We’re already tweaking it quite a bit. So the assignment was a twist, but it was still within the framework of graduate school assignments.

Salty: Another thing that I love about this is that it stretches one’s imagination in terms of our relationship with money— it momentarily turns money into this thing that can make you and someone else happy through the act of creative gifting.

Harrell: Yeah, I had the experience pretty early on, beginning to work with project budgets, when I was collaborating with Jon Rubin, Larry Sultan, and other people that Jon and I were collaborating with in the Bay Area. When we were still in graduate school, or just out of graduate school, we started getting project budgets that were pretty big, like $10,000, $30,000, pretty big chunks of money. This is in the 90s. And I was someone who, at that point, made $10,000 a year—that would be my total income.

And so suddenly, I was working with a project budget that was three times bigger than my yearly income or something. I recognised that it wasn’t my money—a portion of it was mine that I was getting paid a fee for, but the rest of it was money that I got to use to create a project with. And it became fun to be able to spend $1,000 on something that I personally couldn’t spend $1,000 on. But with the project money I could.

It gave me the sense that money is relative, not static, and it means different things to different people in different contexts. It gave me this chance to have fun with money, which seems very privileged, and it kind of was, but it was the circumstance that I got as a basically impoverished artist working with what seemed like big project budgets when I was still in my 20s. It gave me a fluid, flexible feeling about money that I think in some ways allowed me take more risks, to feel like I could run out of money and still be okay, to spend money on things—basically my work—that could seem kind of frivolous from a broader public or maybe a family member’s point of view. I wanted the students to get a little bit of that feeling.

Salty Xi Jie Ng (she/her) is an artist, program alumni, and editor of SoFA Journal. She is based in her home country, the tropical metropolis of Singapore.

Harrell Fletcher (he/him) is the co-founder and director of the Art & Social Practice MFA program at Portland State University.

Going the Extra Mile (Luis Insists on Hardcover)

“What would I be without everybody? Without my customers?

-Luis Orlando Beltran

I did the whole thing backwards. I could’ve picked a simple task, a task that required no money at all, and compensated the commissioned party with the full funds granted for this project as a means of valuing their labor. Instead, I went about it in a much clumsier way. I used it as a reason to hang out with Luis, the affable shopkeeper of my neighborhood thrift store, and decided to figure out exactly what I would pay him for…after the fact.

Every Tuesday and Thursday morning for the month of April, I walked the two blocks from my apartment in Ridgewood, Queens (a quiet residential nook of New York City) to Celene’s Thrift Shop—a clothing, housewares, and bric and brac store no bigger than a corner bodega—with my recorder in hand, and met with Luis to capture his ebullient philosophies on life. We knew the outcome would be some kind of “booklet,” as we called it, and when I tried (multiple times) to explain the part about paying him a hundred bucks, he waved the idea away with his hand and said, “No, no, no.” I tucked the topic away for a later day.

His automatic resistance to the money has to do with the fact that Luis is a man of God. Devoted to his church, Luis organizes bible retreats, goes on missionary trips, translates his pastor’s sermons into Spanish at Sunday service, and recently gave a motivational speech on the lesser known Christian disciple Barnabas, known as the “son of encouragement.” While I live a fairly secular existence and tread lightly with religion, I nonetheless feel warmed by Luis’ customary send off: God bless you, honey. That’s because he really means it.

His store, named after his wife of 44 years, is 182 square feet of fastidiously organized and artfully displayed secondhand items. One wall is devoted entirely to mugs and glasses, another to perfectly folded pairs of pants, each of which is labeled with handwritten tags denoting their size. Somehow, in this tiny shop are also records, gowns, candles, figurines, bedsheets, shoes, games, greeting cards, jewelry, coffee makers, DVD players, and a glass case full of perfumes, all arranged according to category, and often, by color. Luis accepts item donations, and therefore provides not one but two services: a place to acquire new things, and a place to let go of old things. I bring him my things not just because it’s a convenient way to get rid of them, but because I know his shop will consider them treasures, house them affectionately, and foster them until they find a new home. And so the shop exists as a kind of undeclared community general store, where each one of us that comes in is, to some degree, inadvertently exchanging goods with our neighbors by way of Luis’s stewardship. The effect is a feeling of generous flow, an abundance as reliable as the tides. You can pop in on any given day to see if he might have a clipboard, or a suitcase to sell you, because there is a legitimate chance that he does. This, combined with his infectious energy and genuine extroversion, makes Luis, in my estimation, the most popular guy on the block.

“Hiya, Bec!” Luis greeted me upon arrival for our first recorded interview. It was a seasonable Spring day, and I watched as he set up a cup of coffee, a bag of cookies, two oranges, and a knife on three plastic-upholstered dining room chairs he was selling out front. We settled into the spread and I joked that we were a living advertisement for the furniture. Not long after, a man walking by politely interrupted our conversation:

Customer: Hey, how much are these chairs?

Luis: These chairs? Will be fifty for three of them. And $25 for this table— $75.

Customer: Can I take a picture of this chair? I’m so sorry.

Becca: No worries.

Luis: Not a problem.

Becca: We were just saying, we’re an advertisement. [Laughter]

Customer: I’ll be back. I live around here. I bought stuff from you a couple of times. Remember the cage?

Luis: Yes.

Customer: Well I’m gonna come back. I’m gonna see, I like them, that’s a good price.

Luis: Alright, brother.

Customer: It matches my table, too.

Luis: It matches your table?!

Customer: Yeah it matches my table too.

Luis: Ay, let’s do it man.

Over the course of our time together, especially since we were meeting outside, I came to expect these interruptions. The frequent “Good morning” from a passerby, and Luis’s “Buenos dias!” or “Good morning! How are you?” back. The shop sits at a residential intersection, so cars sometimes whizzed by with greetings like, “AY, LUIEEEE!” flying out of an open window. “AY!” Luis would shout back, explaining to me with a grin, “That’s my buddy.”

The chairs sold later that day, purchased by another, more swift-acting customer. So for our second meeting, Luis set up a fold-out card table on the sidewalk next to his minivan, with an overturned milk crate and a stool for us to sit on. This time, there was an additional cup of coffee—for me (“My wife makes me coffee every morning,” he said appreciatively), and again, two oranges and a knife. He peeled one for each of us as he told me about his life. He talked about moving to Brooklyn from his rural town in El Salvador when he was twelve, and learning English from his aunt and uncle’s Engelbert Humperdinck records. He told me about the impact that his first job in New York had on him, learning how to sort and package fruit for produce displays at a local grocery store. He described how his family taught him to dust, sweep, and mop, and tasked him with cleaning their apartment on Kosciuszko Street from top to bottom every day, the summer before he started school in the USA.

He also told me about his struggles with substance abuse, his failed Western Union franchise due to a bad contract and a bad cocaine habit, the day he spent in jail because of a misunderstanding, and how he eventually bottomed out and found his way to God as a means of survival.

I arrived at our sixth meeting with the proof of our book, a condensed and edited selection of his most compelling stories culled from hours of recordings. We sat down once again next to his minivan and together, read through what we had made. Luis seemed to delight in hearing his words read aloud to him, exclaiming, “True! So true,” after each story. He persisted in his resistance to the one hundred dollar financial support from school, and, as a person deeply energized by hard work and a big project, he wondered aloud how we could make it better. “Let’s do it the best we can,” he said, leaning in to ask: “Can we do hardcover?”

~

Becca Kauffman: So here’s what I’m thinking. Here’s a pen, you can mark it up however you want if you have any edits to make.

Luis Beltrán: Ok. I like this, this is nice.

Becca: So this is a really big version, but I’m imagining it will be about five inches by four inches, sort of like a photograph size. So you can hold it in your hand, and that way it will be thicker, too. But the text will still be big enough that you can read it. “Inside Celene’s: Store Stories” is a working title. I just chose it because it’s kind of what we’re talking about.

Luis: Right.

Becca: But I’m open to any ideas. It’s just the starting point.

Luis: I like that. I like that. It goes together, cause it catches the attention. Stories? Stories? What’s in there?

Becca: Yeah, so now we open up and find out what’s inside… So this is the same writing I gave you a copy of last week, but I just formatted it. I put this big text at the top, the quote, that sort of gets you started. And then here’s all the nitty gritty details of what you’ve said. So there’s ten of these. They’re kind of like chapters. We can read it together if you want. I can read it out loud, or you can read it out loud.

Luis: You can read it out loud. Go ahead.

Becca: Okay. Great. So: [Reading aloud]

“It’s amazing how this little place keeps you on your feet.

I love what I do. I’m here seven in the morning, eight in the morning. And I know what I got to do. One thing I gotta say is that I’m not tired of doing it. And health wise, God gives me the strength to carry on. And I’m going to do it until… I don’t know what’s gonna happen… It’s a fountain of energy. Yeah, in a different way I found my match. I’m the manager. I clean the toilets, I sweep, I mop, I organize, I take, I put away.

After we take everything out and we clean inside, I like to sweep even though it’s clean. And I mop. Clean and mop… Sometime during the day, I like to do it once. Like it bothers me I haven’t done that… When it’s the time, it’s the time. There’s a time for everything, like I said. So when it’s, Oh okay, everything was cleaned. It’s amazing how this little place keeps you on your feet. I got a lot of work to do. So that’s how it is.”

Luis: Yeah, that’s nice. It sounds better when you say it.

Becca: I disagree. I like it when YOU say it! But I think it’s an interesting experience to read what you said out loud on paper.

Luis: Because you’re a storyteller.

Becca: So are you!

Luis: But it sounds… No, I like to hear it.

Becca: So here’s the next quote: [Reading aloud]

“Whatever they give me, whatever life gives me, I take care of it.

I was twelve when I started doing produce, because my brother-in-law was a project manager for this Jewish chain of supermarket.”

Luis: That’s produce. Produce manager.

Becca: Ohhh, yeah. That makes sense. Here, cross it out and write “produce.” That’s helpful, thank you. [Reading aloud]

“…It was called Royal Farms in Brooklyn. We had like twenty two stores. In September, after school, my brother-in-law used to take me to work at the basement of that store. And he taught me how to select oranges from apples and all that and wrapped up, put six, six apples in a tray, wrap it up, put a price and all that. So I was like in heaven. So I worked. And through the years, twelve, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, eighteen, nineteen, I knew that trade. So every summer, I used to come to the company and they started giving me jobs. And I was a full time, I was a part time, and I was a manager. Managing became also part of that responsibility of leadership, so to speak, because then you have to do what you have to do to manage. Right. So like freshness, cleanliness, and all that. All those things that I learned, got me, I mean, to be the person I am, I think. Humbly I say it. Because I think those are the little qualities that you pick up in life that you bring with you in those years. And that’s how I, I don’t know, whatever they give me, whatever life gives me I take care of it. Because it’s an opportunity to me to do well, for me to serve the community, to serve somebody else. And so you see, it depends on what you got. If you got lemons, you got to learn how to do lemonade. Right? That’s how it is. That’s how I did it, I guess.”

Luis: [Starts to laugh] That’s the story. I can’t believe it, I’m thrilled. I’m hearing things that I, that we said.

Becca: Yeah! Do you remember them? Do they sound familiar?

Luis: Yes, now it’s coming back to me.

Becca: Here’s photographs of where we were sitting, with you peeling the oranges.

Luis: You’re not there, though!

Becca: I know. You know what we need to do? We need to get a photograph of the two of us.

Luis: Yes.

Becca: Thank you for reminding me of that. Okay, now we’ve got: [Reading aloud]

“People are searching for something. Same thing here! Searching for something.…You listen, people come in need of something.

In church, there’s a principle that when someone comes near, for the first time, second time, we have to pay attention to that person. We have to, “Hi, how you doing today?” We have to like, “Hey, I see you again. Thanks for coming.” Because people are searching for something. Same thing here! It still has the same meaning.

I was in church when I opened this [shop] up. So the first thing I said to the pastor was, this space was a blessing, because it was a blessing. I said to myself, I want this place to be a blessing for people. I want this place to be, they could find something that they are looking for and need. And I said to him, “Do not let me get a hold of items. Do not let me get a hold on this. Let me be free to give it if they need it.” And it has happened. And people have come, people have come, and they come only to say hello, because of the relationship that we already had. I have had people coming back into the neighborhood [to visit] from LA, from Miami. And they come and say hello. “Hello Louie, I thought about you, I was in the neighborhood. And I came to say hello.” I say, “Thank you, thank you thank you.” And they do, they do, they come. Well, and this place, I have had people that come in, and they step in, and I say, “Hi, good morning, good afternoon. How you doing?” And they will start talking about different things. And we wind up healing the soul. Like I say, you listen, people come in need of something. And that’s when the Holy Spirit, I believe, Spirit touches you, and then you touch that person, and that person feels, Wow, I’m glad I came in, I don’t know how I got here—these are the words that they say-—I don’t know how I got here, but I’m happy that I came here, because I found…whatever, you know? They do that.”

Luis: True, true. I’m glad you put that in there. True story.

Becca: Yeah, that was a special one.

Luis: I’m here to say, Yes, it was true. You putting me way up there in my thoughts. This is not only—I’m glad you did this. I’m very glad. Because—

Passerby: Morning.

Luis: [To passerby] Good morning. [Back to me] I’m thinking about— I never thought I was gonna do this. The story of my last years. I’m not ready to go, but, this is something that I’m gonna leave behind. It’s great. It’s great, the thought of it. I want you to be there when you have to read it.

Becca: Oh my gosh, should we have a reading at the store?

Luis: Yeah! Okay keep on going, I don’t want to take your time.

Becca: Okay. [Reading aloud]

“Go the extra mile.

Through this place, I have had people that, they feel good. They come back. Some people, they come in and we sit down inside, we have coffee and we talk about religion, we talk about this. I’ve had people come with problems and they pour themselves out in tears. And sometimes I gone through the same things and I could share something with them. Last week it happened. And they come back and they call me later on, they say, “Luis, thank you for the comfort. For the comforting.” I say, “Don’t worry about it.” The idea of this place, like I said, I pray everyday, and when I pray, I say, Lord, find, get me people that I could talk to. Send me somebody in need, please. And He does. And He has also sent me people for my need. Because I also receive. I do not only give, I receive. Affection; I receive a word of encouragement. I receive, when I’m down, I’m struggling, my mind, I got too much work to do. And I have had people come and offer their help for free to do something for me, because it’s all a mess and all that. He listened to me. He knew me, he knew that I was bothered. So, you know, it’s like, it’s life. To me it’s God. To me it’s, I’m not the person I used to be. I’m a different person. You know, I stopped doing a lot of things that were not good to me or to the society. Change. We all change. Sooner or later, we all change. And the best that we could do is share that warmness, that careness, that ear, lending ear. Or, Listen, I’m looking for this bed frame that was there, and I want it, and let go, to not be greedy. I’m going to sell it to you. Listen, I’ll bring it to you in my car. You want it? It’s yours. Sure. For free? Yes. Take it. Take it, don’t worry about it, we take it in your car. Go the extra mile, go the extra mile. You never know when it’s going to be somebody coming for you for the extra mile.”

Luis: Nice. I remember that. I remember that story. It’s true.

Customer: [to Luis] How’s business today?

Luis: [to customer] Good! You the first customer that I greet with my smile. Bless your heart. Whatever you want— that smile pays for everything.

Customer: [Laughs]

Luis: [to customer] Stop smiling, otherwise you take everything!

Becca: Okay, so here’s a photograph. You, gesturing, which is something you do, I’ve noticed. So on to the next story. This is one of my favorites. “There’s time for everything.”

Luis: Yes. A wise man said. Solomon.

Becca: [Reading aloud]

“If I was a guy [who] did not care much for anything, would I be here sitting with you? Telling you all this stuff?”

Luis: [Laughs] Come on! [Laughs]

Becca: [Continuing]

“…Where I’ve made time to sit down? Is my life more like—I say to myself, right?— is my life more like, doing this business and all that? I try to live a life that is not too rush-y, because there’s time for everything. Sometimes I do get into the rumble, you know, and I rush, because I have to. But I realize that there’s time for everything. There’s time to cry. There’s time to laugh. There’s time to rest. There’s time to sleep.”

Luis: Mm, nice. Nice. It is. That’s a quote from the Bible.

Becca: Really?

Luis: Yes. Solomon, King Solomon. Ecclesiastes is a book in the Bible. And he says that there is time for everything in life and that nothing in life is new. Whatever has been, it’s always been. It’s like a cycle. You know? There’s nothing new in this world. Everything has been already done. In our lifetime, fire has always been fire. The rays of the sun, they always been there from the beginning, and they still are. Imagine, without a sun?

Becca: We wouldn’t survive.

Luis: We wouldn’t survive. And the distance is just right… I went to [a bible retreat in the country recently]. And I started walking in the open space, the birds. Not cement. But trees. No buildings, but grass. And I started to say, Wow, that peace, that complete peace—and I needed that peace—but at the same time, I feel lonely. Like I felt like I left everything behind. I missed this [gestures to the shop]. I don’t know, I missed communicating… My people, my customers, my helper [Ana Yris]. I said, Oh my god, what am I doing here? [laughs]. I feel lonely. But I didn’t know that my mind was taking other kind of oxygen. Not this oxygen. Nothing like this.

Becca: Yeah, I feel like being in nature has a tendency to do that. Because all of the stimuli of city life goes away and suddenly you’re like, What am I left with? Who am I without other people around?

Luis: I felt lonely. And I miss my wife. And I miss everything about New York. Oh my God, if I stay here, by myself, I’ll die. [Laughs] And that’s why, you see those people in the country? They live at their own pace, they got their own things. But not us. And what would I be without everybody? Without my customers? I felt like completely detached. Separate.

Luis: Have you told anybody else the story yet? You know, opinion-wise.

Becca: I showed my mom. I sent this to her last night. She loves it. She loves your stories. And oh, she actually had a different idea for the title. She suggested calling it, “Going the Extra Mile.”

Luis: That’s an option.

Becca: Because that’s a quote from one of the stories.

Luis: Yes. Well, we haven’t finished yet.

Becca: Okay. [Reading aloud]

“How do you know what you want? The need of other people is a start.

How do you know what you want? The need of other people, is one point, it’s a start, in this business, I understand. Or let’s go back forty years ago, people come in and say listen, I need this kind of oranges, size big or small, with seeds, without seeds, and you go and find it. Because your knowledge knows that the oranges, which one has seeds, which ones don’t have seeds. Because life teaches you a lot of things. So, I was an expert in fruit and vegetables. So how do I know? Because the need of other, the need of other is what I want. What I really, really want?—is different than in the business world. For example, there was a lady that is in the neighborhood. She wants earrings that have a little cross. And I had them, [but] I sold them all. I went to find them yesterday and there was none. But she asked me for it. And that’s my need. That’s what I need. I want to get those earrings for that lady. And I will not rest until I find it.”

Luis: She came.

Becca: Yeah?

Luis: She came and asked me, a young girl. And I’m gonna go to get them in Manhattan.

Becca: Yeah, that’s the next part! [Reading aloud]

“Even if I have to go Manhattan. [Both laugh]… And I want to see that. That’s all it takes. I want to do it, I want to have it.

It’s like a winning step up the ladder. You did that. Then after that? I don’t forget what I said. It’s done. The satisfaction is that few seconds of happiness of the person, that, Thank you, you know, or, Here, an extra dollar. I don’t need it, but she wants to compensate what I did. And I’ll take it.”

Luis: Life always gives you compensation. You never know when. For your good deeds. For that extra mile. That happens to everybody. Sometimes we don’t see it.

Becca: Final chapter. [Reading aloud]

“I see it as a gift.

I’m surprised that for ten years I’ve been doing this. And I’m still going with it. I’m still happy to do it. What else would I be doing? You know? And every morning is different. Somebody comes in with different things, even though it’s the same but it’s different, a gift, that they give me. I see it as a gift, you know? I see it as a blessing.”

Luis: It is.

Becca: [Showing the book’s last picture] I thought it was nice to end with the open door to the store.

Luis: Yes. And the blessing. That makes sense. Yes.

Becca: And then this would be the back cover. I wrote “Established 2011,” because you said you’d had the shop for ten years, but is that the right year?

Luis: I was gonna look for that. [Opens his wallet and unfolds a piece of paper] This is the certificate.

Becca: What! You carry this in your wallet? So cool.

Luis: Because when you go into business, some people, they ask you for the certificate. It’s a copy. And here, we have the date.

Becca: Which is… August 4, 2011.

Luis: So 2011 to 21. It is ten years.

Becca: So August 4th of this year is your ten year anniversary. Maybe that’s when the block party should happen!

Luis: Yes! So, very, very nice. I love it. I really, really love it. I’m so happy. I’m very, I’m very happy.

Becca: Well, it’s all you, you know, it’s your story.

Luis: I wouldn’t have done it without you.

Becca: It’s a good collaboration.

Luis: Yes, it is. It sounds so good. And so true. How can we make it better?

Becca: Okay, that’s the question. So now comes strategy about how the actual book will look. I think we have to think about, who do you want to share these stories with? And how can we make it accessible for those people?

Luis: Can we make copies?

Becca: Yeah, absolutely.

Luis: Can we make it like a real…

Becca: …book?

Luis: Book?

Becca: Yeah.

Luis: In like, hardcover? …Give me an estimate. Let’s do it the best we can.

Becca: Okay. So we have $100 to spend. This project, we call it the $100 Commission. The idea is that my institution gives me $100 to fund a project with somebody else. So I have this one hundred dollars to spend.

Luis: Yes.

Becca: So it’s like, I’m an artist, but right now I’m kind of wearing the hat of a bookmaker or a publisher: I want to make a book.

Luis: Okay.

Becca: And I want you and your stories to provide the content for that book.

Luis: Okay.

Becca: So in a way, it’s like I’m commissioning you to share your stories, so that we can make this book together. And we can use the $100 for publishing materials to print it out. I can find out how much it will cost to do a hardcover. And to do color.

Luis: Yes.

Becca: If there was anything left over, I would give it to you, donate it to the shop.

Luis: No. Let’s do something nice. Don’t worry about the price. Just find out. You know, give me the expense details.

Becca: Well, I don’t want you to pay for this.

Luis: But I do, I want to, because I want not only… I love the story, I love the point. For me, it’s very important. So that we could make a nice, real book. So that I could give it to my kids.

Becca: Okay.

Luis: Alright. And also, I want you to present, because at one point, you’re going to present this to the school, right?

Becca: I will.

Luis: Well what do you want to do with it?

Becca: My wish is that other customers who come into your store could also obtain a copy.

Luis: Okay.

Becca: So whether that means it’s available for free, and you throw it in with, you know, a purchase over $20, or maybe there’s some kind of cool little display, like a stand, that we could put the books on. And you could have a place in your store so that when people come in, and they’re like, “This is such a great shop, what’s the story here?,” you’re like: “Buy my book.”

Luis: [Laughs, applauds] That’s beautiful. Good idea, yes!

Becca: So in that case, especially if it’s a really nice object, then maybe you do sell them for a little bit of money. If we end up investing a little bit more in the quality of the book itself, it will make more sense to charge a couple dollars for it. What do you think?

Luis: Don’t worry about it, that’s not an issue, because I want… You see, there are people that come and are very interested and they love my shop. And it wouldn’t be fair for me to charge them for a book. I will give them with all my heart. You know?

Becca: Yeah.

Luis: “I’m glad you love my shop, I’m glad you love this store. This is us,” you know? And that book will travel and travel. Just the fact that we have a story about this, that’s my goal. And whatever it takes to make it a better story, we can work on it. If you have the time.

Becca: I do. In terms of the style of the book and how we present it, I want to design it around how you envision the exchange that you would have between someone who walks into the shop and loves it and wants to know more. Like, what kind of book would you feel comfortable saying, “Here, take this with you?” Do you have a picture of how big it is, what color it is, if it’s on display somewhere? And is this title something you feel like represents you and the store and how you want to be seen?

Luis: Okay. Is this gonna be like the front? No, that’s not going to be the—

Becca: This is a draft. It could be anything on the front.

Luis: We got to find something else. And the name, I like this name because it was first but I love your mother’s idea too.

Becca: “Going the Extra Mile?”

Luis: Yeah. Because it is an effort being accomplished. And you know what, it comes in a time of need, of the times that we are living. You know, it’s a business, but at the same time we are helping the community, right? We doing it for the community. And going the extra mile is helping people. Going the extra mile is providing for people. And the colors [points to the blue and yellow Celene’s Thrift sign on the building]. I would like to use those colors.

Becca: Oooh! Okay.

Luis: Because it has to go all according to the store… My son-in-law, he has a printer. We could get him involved. He prints t-shirts and hats.

Becca: Good to know for your ten year anniversary.

Luis: Yes! T-shirts.

Becca: I would definitely buy one of those.

Luis: Ten years anniversary and—

Becca: Ooh, a big sign!

Luis: A big sign! Now you got me going with this.

Becca: It’s good to think ahead. I mean, August isn’t even that far away. We could make these books before then, and make sure to have them there for your ten year anniversary. Maybe that’s the premiere of the book.

Luis: Everything. It comes along!

Becca: So it could be important to note on the back, like, “In honor of the ten year anniversary of Celene’s Thrift shop, this collection of stories.” And maybe that’s part of the reason why we publish it?

Luis: No, well, I’m doing this because I want you to, for your school, for your project.

Becca: But MY project is to facilitate and support YOUR project! [Both laugh] It would be perfect if there’s a ten year anniversary party, and then this book just fits right into that.

Luis: It would. We’re gonna do that. We’re gonna celebrate. We’re gonna put balloons, we’re gonna do something for everybody. We gotta announce it before. We could, you know, play some music. Celebrate. Make a celebration. I don’t see why not.

Becca: How many copies do you think? I can price stuff out, but I was hoping like, fifty?

Luis: Yes. Something like that.

Becca: Think that’s enough? We could always reprint it if it’s popular and they sell out and we want to keep going.

Luis: Let’s start with fifty. I want to take the funding. I want to fund it. I want to pay for it.

Becca: Noooo!

Luis: Yes. Because I love the story. It’s all about us. And it’s about you. But I want you to have some, and I want to have some. It’s not fair, that you, you came up with the idea, and I love the story, and everything is being created. And I want to fund it.

Becca: That’s very generous.

Luis: A hundred dollars isn’t gonna do.

Becca: Well, I know.

Luis: You know that!

Becca: I’m going to do as much as I can to fit it into a hundred dollar budget. I’m gonna do the best I can. And then yeah, I’ll let you know. I’ll ask around this week.

Luis: Ask around, take your time, and work on it, and let’s make something very nice. Okay?

Becca: Okay. Cool. Thank you!

Luis: Thank you, Becca.

Becca: It’s been so fun.

Luis: Oh, yes, it has. I’m happy.

Becca Kauffman (she/they) is an artist living a block away from Celene’s Thrift shop in Ridgewood, Queens. They are a first year in PSU’s Art and Social Practice MFA program currently investigating the voice as an artful and multifaceted communication device.

Luis Orlando Beltran (he/him) was born in El Salvador, Central America and moved to the United States in 1969. He went to high school in Brooklyn. He’s never written a book before, but has a lot of stories. He has worked as a produce manager, a vacuum and encyclopedia salesman, a chauffeur, a check-cashing clerk and franchise owner, and now runs his own thrift shop, where this story begins.

A Book for the Travel Ritual

“I like this project because the only certainty in life is that we will pass away, and we would like our children to remember us. I tell my son, ‘When I die, take me to Mexico.'”

Text by Diana Marcela Cuartas

Translated by Camilo Roldán

Spanish version below

I arrived in Portland in the fall of 2019. With nearly ten years of experience working with arts organizations in Colombia, I spent the entire Fall trying to find work in the art world in this new city. After months of searching without results, I wound up in the world of social work. I suddenly became a Family Engagement Specialist, and my mission was to support Latin American immigrant families as they navigate the school system and to foster an interest in education. In this new role, my first “client” was Reyna R., a Oaxaqueña with a curious and collaborative spirit. From day one, I was inspired by the strength she showed in pushing her own limits and learning new things. Beyond work, circumstances have helped us to build a friendship and a shared learning process.

As an artist immersed in an unconventional form of employment, I am interested in how art can impact other systems and professions—in this case, social work. Interviewing Reyna seemed like a perfect opportunity to experiment with my role as an artist-social worker in a timely way. I offered Reyna my bookmaking services to produce a small book of her choice, and I gave her the 100 dollars as a stipend for the interview. Reyna accepted and decided that she is interested in making a book for her family about Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). The following conversation is a starting point for what this project may become.

Diana Marcela Cuartas: Hello Reyna, tell us where you are from and when you arrived in Oregon.

Reyna R: I’m from Oaxaca, Mexico, from San Miguel Cuevas, in Juxtlahuaca, Oaxaca. I came to Oregon in 1998.

Diana: And what brought you here?

Reyna: I came to work during the fruit harvest—with blackberries, strawberries or blueberries—in a processing plant.

Diana: And did you like it?

Reyna: Yeah… I worked at night. It was hard for me, but at night I could get overtime.

Diana: And why did you decide to stay here?

Reyna: I liked the weather. It isn’t as it is in California. I used to live in Raisin City, California where I worked harvesting grapes and trimming the vines, it was a lot of really hard work.

Diana: So here you could do work that was just as hard, but with cooler weather.

Reyna: Yeah, it was easier.

Diana: And have you ever collaborated on an art project?

Reyna: No.

Diana: How do you feel about the opportunity to create your own book? Keeping in mind that what I proposed were my services in making it, plus a small payment in recognition.

Reyna: I feel a little bit nervous. It’s unbelievable to me. I never thought about making a book. I don’t even know where to begin.

Diana: But do you think it’s worth it?

Reyna: Yes. There’s nothing to lose. On the contrary, I’ll gain a little bit of experience. And, you know, I can remember what my hometown is like, how they celebrate fiestas there.

Diana: And why did you choose Día de los Muertos as a subject?

Reyna: I think it’s because I really like Día de los Muertos, but also, when we went to see the movie Coco, my son said to me, “When I die, put this and that on my altar.” “Oh no!” I said, “Your mother is going to die first, and you’ll die later on.” But it’s a beautiful tradition because Día de los Muertos is when our families come back to visit us, to live with us. That’s what people believe.

Diana: So, it’s also to leave this knowledge behind for your family?

Reyna: Yes, for the children. Because living in this country, we lose a lot of our original culture because we don’t practice it. And if I don’t do it myself, they’re even less likely to do it. So, when I’m gone, at least they’ll come to see me. I didn’t use to celebrate it, but when one of our pets died, for whom my youngest son was a “father,” he said, “This year we will make an altar for Mila.”

Diana: How long ago was that?

Reyna: We made the altar two years ago. This will be the third year.

Diana: I wanted to ask you, what is your relationship to art, or what do you think art is?

Reyna: Well, to me, art is… I imagine colorful drawings.

Diana: Because what we’re going to do is art. This little book will be a work of art that we’re going to make together. Maybe you haven’t drawn before, but would you like to draw?

Reyna: Oh no, I’m really bad at drawing. I have two left hands.

Diana: I ask because, to me, for example, art is more like a way of doing things.

Reyna: Like a way to express yourself? Like, if you don’t know how to do it one way, you can do it another way?

Diana: I think so. I see it as a way to present an idea in the coolest way possible. Like when you put lime or hot sauce on things. The plan will be to share your knowledge in a format we like best.

Reyna: That sounds good.

Diana: What do you expect from me as a collaborator and producer?

Reyna: That you show me how because, well, I haven’t the slightest idea. Like I said, to me, it’s incredible that I can help you to do this because, well…

Diana: But I’m the one who will be helping you! And ok, you say you want me to teach you, but what do you want to learn?

Reyna: How to better describe things, and how to write about them so that people will understand.

Diana: Yeah, I can do that. Now, tell me, what do you think about the $100 payment for something like that?

Reyna: I think it’s fine.

Diana: It makes me think about the difference in the value of money here and in our countries. When I first came here, every time I went to pay for something, I thought, “This is going to cost 3 dollars, that’s 9,000 Colombian pesos—it’s so expensive!”

Reyna: 100 dollars in Oaxaca is a lot of money, but here not so much. You can pay for some things, but it isn’t much. In Oaxaca, you could buy a lot more stuff. Because here you go to the store and you can’t buy anything with 100, even less if you go to Costco. My god! But wherever you go things are expensive, here and in Mexico. Wherever.

Diana: Ok, and how do you imagine the project we’re going to make? Without thinking about the fact that we still don’t know how we’re going to do it. If we had a magic wand and, “Ta da! it’s done,” what do you imagine?

Reyna: At the end there needs to be a photo of the altar for my “granddaughter.” And, I dunno… we should say why people do this, and describe everything you place there. That you collect the wood little by little, buying the little things, so when the day comes around you have everything. From making the mole and all the food, because it is a long process where men definitely have to help out. Because they have to decorate the tabletop altar for the saints. And the women are in the kitchen.

Diana: And do you see yourself sharing the result with the groups you belong to, like Guerreras Latinas or the Oregon Food Bank where you volunteer?

Reyna: If I can, sure. They should take a look to see what they think. And more than anything it would be a book for children, I think. I imagine it that way, with cartoony drawings or something really colorful that holds their attention, because children are the next generation, and it’s up to us, their parents, to teach them.

Diana: Okay, so the book needs to have colorful drawings. And you also told me that it should be in both languages.

Reyna: So that those who don’t speak Spanish can also understand it.

Diana: What’s most exciting to you about this project?

Reyna: I like this project because the only certainty in life is that we will pass away, and we would like our children to remember us. I tell my son, “When I die, take me to Mexico.” Because if they bury me here they have to make a payment every month that I’m in the ground, and if they don’t, someone will dig up my bones. Better to be in Mexico. There they’ll know where to go to visit me. Just yesterday he was saying to me, “Mommy, when you die I’ll go on my days off to bring you flowers and chat with you.”

Diana: Do the two of you talk about death a lot?

Reyna: Right now, yes, because my husband’s grandmother just died on Thursday. Over in Oaxaca. But she didn’t die of COVID, she was just very far along, she was 99, was going to turn 100 in August.

Diana: My grandfather also died at 99. He left us when we had nearly put together the party for his 100th. He died in April and was going to turn 100 in September. My aunts and uncles wanted to throw a big party and had been saving up since he turned 99.

Reyna: They were also saving up here for a big party, because she’s the pillar of their family. But she left us on Thursday, and that’s it, she died.

Diana: And tell me, what is Día de los Muertos and why do you have to prepare to celebrate it?

Reyna: Day of the Dead is October 31st, which is Halloween here, but in Mexico we celebrate it differently. We don’t ask for candy. There we celebrate with food because it’s the month when those who came before us come back to visit us and to eat. You have to prepare the totopos a month in advance because they’re made with fresh corn, and it takes time to make them. When I would make them, my father would say, “Don’t eat them. Even if it’s broken or burnt, don’t eat it because they have to eat first.” And I had to hold out and not eat those tortillas that smelled so good. But he said, “You have to show respect until they eat, and then we can.”

You also decorate an altar. You put out bread, lemon, oranges, sugar cane, plantain, pan de muerto—that bread in the shape of a skeleton. There are small ones for commemorating children who have left us, which we do on October 31st. For them, you put out rice pudding, candy, fish broth, small tortillas and little breads. The adult’s day is November 1st, and then you put out big tortillas, aguardiente, cigars, beer, mole, chayote, fig-leaf gourd, or whatever the deceased would like. The decorations should be made in the preceding week, otherwise the flowers, which are Mexican marigolds, will wilt. I remember my father would go into the hills to find some flexible cane to build an archway that he would fill with flowers. You also put out a lot of candles and votive candles, which are a light to guide them.

For the little dog’s altar, I didn’t make an arch. I only got the flowers and put them in a vase. I did buy bread and put some Maseca tortillas out for her, but it isn’t the same because it doesn’t smell as good as when you make fresh tortillas.

Diana: Because the smell is what matters.

Reyna: The smell is what the dead consume. I mean, they come to eat, but they come only to smell the food.

Diana: And do you play music?

Reyna: Yes. On November 2nd you go to the cemetery, and a live band from the town shows up and you tell them to play here or there. And they go and play where your dead loved ones are. Also, the priest is there, and you tell him to bless the tomb of your loved ones, and he goes and blesses it. You spend almost the whole day in the cemetery with them.

Diana: And, for example, here in the United States, where you don’t go to the cemetery, how do you conclude the ritual?

Reyna: With prayer. Praying for the dead just in your house.

Diana: In the movie Coco, I remember that the animals became alebrijes, sort of fantastical creatures. Is that really part of the tradition, or something Disney invented?

Reyna: My great grandmother told us to be nice to dogs because dogs would help us to cross the river the day we depart, but I’m not sure if that’s true. She also said that it was better to have a dog that isn’t white, because a white one would say, “Don’t ride on my back because you’ll get me dirty.” But Mila was white as snow.

Diana: I think we need some drawings of what Mila would look like as an alebrije.

Reyna: I think so. I’m going to tell her “father” to draw her.

Diana: Because if all of this came about for Mila, then we have to include her.

Reyna: Yeah, like I said, I didn’t do this until she died.

Diana Marcela Cuartas (she/her) is a Colombian artist and first year student in the Art and Social Practice program at Portland State University. In 2019, she moved to Portland and has been working as a social worker for Latino Network, serving immigrant families through school-based programs at the Reynolds School District in the East Multnomah County area. As an artist, she is interested in studying how art relates to and affects other disciplines and systems, in this particular case, social services.

Reyna R. (she/her) is a mom of three children, two of them students in the Reynolds School District. In addition, Reyna works as a caregiver of elderly people, as well as volunteers with the Oregon Food Bank Program and the Multnomah County Líderes Naturales group. She is also a member of the Guerreras Latinas Community and participates in Latino Network’s Colegio de Padres Program.

UN LIBRO PARA EL RITUAL DE VIAJE

Diana Marcela Cuartas con Reyna R

«Este proyecto me gusta porque lo único seguro en este en este mundo es que nos vamos a ir y nos gustaría que nos recordarán nuestros hijos. Yo le digo a mi hijo “el día que me muera llévame a México”»

Llegué a Portland en el otoño de 2019. Por mi experiencia de casi 10 años trabajando con organizaciones artísticas en Colombia, estuve todo ese otoño tratando de encontrar empleo en el mundo del arte de esta, mi nueva ciudad. Después de meses de búsqueda sin resultados, terminé por casualidad en el mundo del Trabajo Social. Me convertí de repente en Family Engagement Specialist, y mi misión sería apoyar familias Latinas inmigrantes a navegar el sistema escolar y motivar interés en la educación. Bajo este nuevo rol mi primera “clienta” fue Reyna R, una oaxaqueña de espíritu curioso y colaborador. Desde el primer día me pareció inspiradora su fuerza para empujar los propios límites y aprender cosas nuevas. Más allá del trabajo, las circunstancias nos han ayudado a construir una amistad y un proceso de aprendizaje recíproco.

Como artista inmersa en un ambiente laboral no convencional, me interesa explorar cómo el arte puede impactar otros sistemas y profesiones; en este caso, el trabajo social. Entrevistar a Reyna me pareció una oportunidad perfecta para experimentar con mi rol de trabajadora social artista de una manera más puntual. Le ofrecí a Reyna mis servicios profesionales para producir un pequeño libro de su interés, y los 100 dólares como un estipendio por la entrevista. Reyna aceptó y decidió que le interesa crear un libro acerca del Día de los Muertos para su familia. Esta conversación es un punto de partida sobre lo que este proyecto puede llegar a ser.

Diana: Hola Reyna, cuéntanos ¿De dónde eres y hace cuánto llegaste a Oregon?

Reyna: Yo soy de Oaxaca México, San Miguel Cuevas, Juxtlahuaca Oaxaca. A Oregon llegué en 1998.

Diana: ¿Y qué te trajo por acá?

Reyna: Me vine a trabajar la temporada de las frutas frescas como la mora, la fresa, y la blueberry en una procesadora de fruta.

Diana: ¿Y te gustó?

Reyna: Si, sí… trabajaba de noche. Se me hizo pesado pero pues de noche podía hacer overtime.

Diana: ¿Y cómo decidiste quedarte por aquí?

Reyna: Me gustó el clima. No hace tanto calor aquí como en California. Antes vivía en Raisin City, California. Allí trabajé piscando uva y podando las viñas, era mucho trabajo y muy pesado.

Diana: Entonces aquí se podía hacer el trabajo igual de pesado, pero con menos calor.

Reyna: Sí, más fácil.

Diana: ¿Y alguna vez has colaborado en un proyecto de arte?

Reyna: No.

Diana: ¿Cómo te sientes con la posibilidad de crear un libro tuyo? Teniendo en cuenta que lo que te propuse fue mis servicios para producirlo, más un pequeño pago en reconocimiento.

Reyna: Me siento un poco nerviosa. Para mí es como algo de no creer. Nunca había pensado en hacer un libro. No sé ni por dónde empezar.

Diana: ¿Pero crees que vale la pena?

Reyna: Sí. No voy a perder nada. Al contrario, voy a agarrar un poquito de experiencia. Y pues para recordar cómo es mi pueblo, cómo se festejan las fiestas de allá.

Diana: ¿Y por qué escogiste el Día de los Muertos como tema para esto?

Reyna: Creo que porque me gusta mucho el Día de los Muertos, y más cuando fuimos a ver la película Coco y mi hijo me dijo “Cuando me muera ponme esto y esto en mi altar”. “¡Ay no!” le digo, “tu madre se va a morir primero, luego tú”. Pero es una tradición bonita, porque es cuando regresan nuestros familiares a visitarnos, a convivir con nosotros, esa es la creencia.

Diana: Entonces ¿es también para dejarle ese conocimiento a tu familia?

Reyna: Sí, a los niños. Porque estando en este país mucha cultura de donde venimos se pierde porque uno no la practica. Y si uno mismo no lo hace, menos ellos. Así cuando yo falte, al menos que me vayan a ver. Yo no celebraba, pero desde que murió una mascota que teníamos, de la que mi hijo el más chiquito era el “papá”, pues él dijo “Éste año sí le vamos a poner un altar a la Mila”.

Diana: ¿Eso hace cuánto fue?

Reyna: Eso fue hace dos años que lo pusimos. Este sería el tercer año.

Diana: Te quería preguntar ¿Cuál es tu relación con el arte, o qué piensas que es el arte?

Reyna: Pues para mí el arte es… yo me imagino que es dibujos con colores.

Diana: Porque lo que vamos a hacer es arte. Este librito va a ser un trabajo artístico que vamos a hacer entre las dos. De pronto tú no has dibujado pero ¿te gustaría dibujar?

Reyna: Ay no, yo soy muy mala para dibujar. Tengo dos manos izquierdas.

Diana: Te pregunto porque para mí, por ejemplo, el arte es más como una manera de hacer algo.

Reyna: ¿Como una forma de expresión? ¿Que si uno no lo sabe hacer de una forma, se puede hacer de otra?

Diana: Yo creo que sí. Yo lo veo como una forma de entregar una idea de la manera más chévere posible. Como cuando uno le pone limón o chile a las cosas. El plan sería compartir un conocimiento que tú tienes de la manera que más nos guste.

Reyna: Suena bien

Diana: ¿Tú qué esperas de mí como colaboradora/productora?

Reyna: Que me enseñes porque pues yo ni idea. Como te digo, para mí es increíble que yo te ayude a hacerlo porque pues…

Diana: ¡Pero yo soy la que te va a ayudar a tí! Y bueno, dices que te enseñe pero ¿qué quieres aprender?

Reyna: Cómo describir mejor las cosas y cómo escribirlas para que la gente entienda.

Diana: Sí, yo puedo hacer eso. Ahora cuéntame ¿qué piensas del pago de $100 por algo así?

Reyna: Creo que está bien.

Diana: A mí me hace pensar en lo diferente que es el valor del dinero aquí y allá en nuestros países. Cuando recién llegué aquí, cada que iba a pagar algo pensaba “Esto vale 3 dólares, son 9000 pesos Colombianos, ¡está carísimo!”

Reyna: 100 dólares en Oaxaca es bastante dinero, aquí no tanto. Sí puedes comprarte algo pero no es mucho. En Oaxaca podrías comprar muchas más cosas. Porque aquí va uno a la tienda y no compra uno nada con 100, menos si va a Costco. Oh my god! Pero dónde sea, están caras las cosas, aquí y en México. Donde sea.

Diana: Bueno, y ¿cómo te imaginas el proyecto que vamos a hacer? Sin pensar que todavía no sabemos cómo vamos a hacerlo. Si tuviéramos una varita mágica y “tarán, ya está listo” ¿tú qué te imaginas?

Reyna: Al final tiene que haber una foto del altar de mi “nieta”. Y pues no sé… poner porqué uno lo hace, y describir todo lo que uno pone. Que poco a poco se va juntando la leña, comprando las cositas para cuando llegue la fecha ya tener todo. Desde hacer mole y toda la comida, porque es un proceso largo en el que los hombres tienen que ayudar ahí sí. Porque tienen que decorar el altar que es donde están los santos en la mesa. Y las mujeres, pues en la cocina.

Diana: ¿Y te imaginas compartiendo el resultado con los grupos de los que haces parte, como Guerreras Latinas y el Banco de Comida de Oregon donde eres voluntaria?

Reyna: Si se puede, sí. Que den su vista a ver qué opinan. Y sería algo más que nada como un libro para niños, creo. Me lo imagino así con dibujos de caricatura o algo bien colorido, que le llame la atención a los niños, porque los niños son las nuevas generaciones y a nosotros los padres nos toca enseñarles.

Diana: Okay entonces el libro tiene que ser colorido y con dibujos. Y me habías dicho también que estuviera en los dos idiomas.

Reyna: Pues para los que no hablan español lo entiendan también.

Diana: ¿Qué te entusiasma más de este proyecto?

Reyna: Este proyecto me gusta porque lo único seguro en este en este mundo es que nos vamos a ir y nos gustaría que nos recordarán nuestros hijos. Yo le digo a mi hijo “el día que me muera llévame a México”. Porque si me entierran aquí tienen que pagar cada mes mientras yo estoy enterrada y si no, me sacan mis huesitos. Mejor en México, allí saben dónde ir a verme. Justo ayer él me estaba diciendo “Mami cuando te mueras voy a ir los días de mi descanso a llevarte flores y a platicar contigo.”

Diana: ¿Ustedes hablan mucho de la muerte?

Reyna: Pues ahora sí porque apenas murió la abuelita de mi esposo el jueves. Allá en Oaxaca. Pero no murió de COVID sino que ya estaba grande, 99 tenía, iba a cumplir 100 en agosto.

Diana: Mi abuelito también se murió a los 99. Nos dejó con la fiesta de 100 años casi armada. Se murió en abril y cumplía los 100 años en septiembre. Mis tíos querían hacer una gran fiesta y estaban ahorrando desde que cumplió los 99.

Reyna: También acá estaban ahorrando para celebrarlo en grande, porque ella es la raíz de ellos. Pero ya el jueves se fue y pues ya, se murió.

Diana: Y cuéntame ¿qué es el Día de los Muertos y por qué hay que prepararse para celebrarlo?