Conversations On Everything: Interviews Winter 2021

Cover

As part of an assignment, my classmate Rebecca Copper mailed me a letter last winter. I gasped when I pulled it from my mailbox because on the back of the plain business envelope were outlines of her hands traced in blue ballpoint pen ink. The gesture seemed so obvious and yet I’d never encountered it nor thought of it on my own. Its intent was potent and stayed on my mind. Seeing those interlaced fingers made me feel as if her hands were passing me the note directly from her desk in Ohio to my own in Oregon.

While designing the cover for this issue, Rebecca’s envelope popped into my head. I thought of the intertwined fingers representing the exchange of ideas and wisdom that happens during a dialogue. These “conversations on everything” are not dependent on face to face interactions. Rather, they happen across media⸺email, video, phone⸺and hold the promise of connection with each other and now, the readers of SoFA Journal.

Cover design by Laura Glazer

Artwork by Rebecca Copper

Letter from the editor

In this second issue of Conversations on Everything, art & social practice graduate students continue their artistic inquiries by spending time in dialogue with artists, curators, boxers, undergraduate students, a livestock apprentice, a third-grade student photographer and their mum, as well as a Times Square security guard.

Editing my way through all the conversations feels like I’m traversing wildly different landscapes with a common value—the desire to build connection and an equitable world in the face of today’s violence. Lisa Jarrett, a professor in the art & social practice program, has a practice that is deeply rooted in the formulating of questions. Questions do not need answers. They can be poetic mysteries that open more doors. Seeing work through the questions they ask, or rather, that I formulate for myself on the behalf of its creators, helps me imaginatively frame inquiry and makes the work more expansive.

Here are my questions about the conversations in this issue, in the order published. Many concern privilege, power, self-knowledge and identity. I hope you find your own questions and in so doing, learn something new about yourself.

How do the members of a radically inclusive art project within a legacy sport practice view themselves and their community?

What did the strangers say?

How does caring for livestock expand an art practice?

What do I have to do to know me?

What is the impact of whiteness on Black creatives?

How can I convince everyone they are qualified?

How can we give children more power?

What makes an interview?

What is the profound vernacular conduit that can help invite someone into a shared space?

What art school would you create?

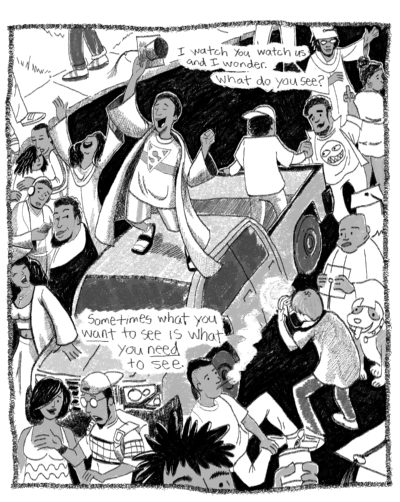

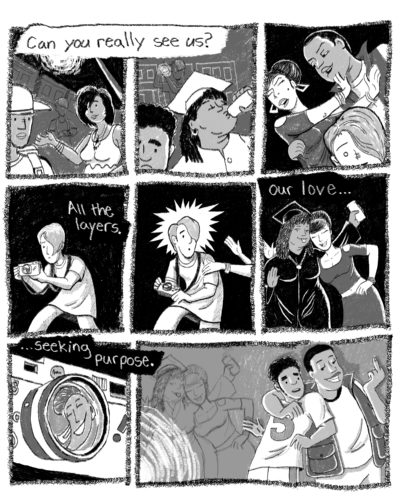

What is still truly obscured and how much of it is by choice?

How can people of color take up more space in museums in ways that are visceral, embodied and ritualistic?

As the trickster looks in the mirror they hear someone call their name; what is it?

Salty Xi Jie Ng is an artist co-creating semi-fictional paradigms for the real and imagined lives of humans within the poetics of the intimate vernacular. She is from the tropical island metropolis of Singapore and is an alumni of the Art & Social Practice MFA program. Salty receives letters to the editor at xi3@pdx.edu.

Talking About Trans Boxing

“When I look at the Trans Boxing class on Zoom in the grid view, I’m like yo, this is deep. It’s really dope. I think it’s a way of actually creating that representation within our group that we’re looking for outside.”

– Eleadah Clack

In the fall of 2013, when I was an undergraduate student at the University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee (UWM), I took a course with Dr. Shelleen Greene called Multicultural America. As part of the class, we worked with the Pan African Community Association (PACA) – a non-profit organization on Milwaukee’s north side which offers after-school programs and assistance to African immigrants and refugees. Throughout the semester, each UWM student paired up with a PACA student to create a collaborative digital storytelling project that shared their stories about migration and learning new cultures.

The collaboration facilitated an engagement with members of the community that I wouldn’t otherwise have had—and it also supported a deeper understanding of the ethnic studies concepts and theoretical frameworks I’d been introduced to in the class. The student I worked with was named Juma, and the experience of working with him had a lasting and profound impact on my life as an artist.

This term, I designed and taught my own class at Portland State University (PSU), an opportunity offered to me by Harrell Fletcher, the director of the Art and Social Practice program where I am completing my MFA, and made available through the advocacy and work of Ellen Wack, an Administrative Coordinator in the department of Art and Design.

The seminar class, called Relational Art and Civic Practice, is designed to support students with conceptual development as well as in-practice application of the strategies involved in socially engaged art projects. In addition to lectures, readings, and discussions, I wanted to give the students hands-on experience with a project.

Ellen asked me if I wanted to add a community-based learning component to the curriculum, and it seemed like an obvious decision to partner with my project, Trans Boxing. Conversation has been central to my artistic practice and education, and so I wanted to create a context in which PSU students and Trans Boxing members could be in dialogue with one another. To do this, I created an interview assignment.

After doing some initial research on Trans Boxing, the students were asked to generate a set of questions they’d like to ask participants. I went through and selected the questions I found most interesting, which would be used to guide our group interviews with Trans Boxing participants. I thought a group interview would be beneficial for multiple reasons. In addition to generating content for written interviews and posters– the format provided a framework for dialogic learning. The context that was created allowed two otherwise unaffiliated groups to come together and discuss trans identity, belonging, athletics, and a whole host of other related topics.

The excerpted conversation is from two group conversations I guided between Trans Boxing members and students from my art seminar course at PSU, which took place on Zoom on Tuesday, February 16th and Thursday February 18th, 2021.

Bri Graw (Portland State University): You’ve all been talking about representation, and what it means to be an openly trans athlete in terms of how important that is for younger generations to look to. Where have you sought inspiration for your own representation?

Maggie Walsh (Trans Boxing): That’s a great question. I mean, I definitely didn’t have it growing up at all. I remember joining the softball team and learning that being successful at softball meant that in addition to the skill, you also had to make sure that you weren’t labeled like, the “dyke player.” So, I had to create representation on my own. Like even if it was something that I could intellectually understand in an academic way or something, applying it in terms of like a sport hadn’t been something that I had consciously done until I felt like I was welcomed into a space that was doing it just naturally.

Eleadah Clack (TB): Yeah, just from my experience as a queer masculine Black lesbian, you do have to look for representation in things that don’t necessarily look like you sometimes. You have to create it. If you look at the Trans Boxing class, that’s a powerful image just to look at it in a grid view. Like I don’t do it frequently because I’m usually watching myself while I do the drills, but like when I do, and I’m sitting there like, Yo, this is really deep. It’s really dope. Everybody’s so focused on themselves, but at the same time we’re coming together. And I think that’s a way of actually creating that representation within our group that we’re looking for outside. We all experienced similar marginalization. It’s not even like we have to really speak on it, because we know that. But then also seeing each other strengthen and grow… it is creating the representation that we want to see for real.

Eniko Banyasz (PSU): I actually went to one of the recorded Trans Boxing classes. I was too shy to go to a live one because I haven’t worked out with other people in so long. After warming up and then hearing the instructor be really supportive, like, “Yeah little bit more, just 10 more seconds!” I was like, “Yes, yes!” And then I did it. I felt like I accomplished something so great. My experience in high school PE education was so bad because you constantly have to compare yourself to national averages. And, you know, you’re put into these boxes. And I feel your success in physical education should be so personalized.

Baer Karrington (TB): Yeah, high school is traumatizing in a lot of ways, especially if you’re not out and especially around sports, which are so gendered. I work in pediatrics and I do a lot of work with gender expansive children or young people, and so it’s been really powerful for me to out myself as a trans athlete, so I can potentially be a gateway for young people who really struggle with finding a space that feels safe for them. I want to show them that there are spaces that are safe and that validate our identities.

Bri (PSU): Yeah, Baer, going off of that, I wanted to ask, how has this experience affected other parts of your lives?

Maggie (TB): I think that it’s given me the ability to take different parts of my life and start blending them together. I think it’s easy to kind of let certain facets of your identity just be parts of your identity and exist in different spaces. And I think that’s true of everyone. I don’t think that’s just a genderqueer thing. But, as I developed a new identity as a boxer, and as an athlete, I saw how that could be blended in with both my personal life and social life.

For example, my boss is a huge boxing fan. And like, we ended up going into a boxing match together. It became like a tool for us to talk about other issues and other things at work. So in a way, I think it’s given me a new language and a new confidence to sort of blend all these different things together that maybe previously were easier to keep compartmentalized.

Eleadah (TB): Boxing is such a technical sport, and it helps me move through a lot of other spaces where there’s not a lot of nuance or technicality. Because I have this knowledge, if I’m in a space it’s like, Oh but there is nuance, because I’m here and I know how to do this on the ropes, I know how to turn my body this way…

Dane Kelley (PSU): How do you feel about other members of the group, and what kind of connections have you made through participating in Trans Boxing?

Brionne Davis (TB): I like that it’s like, we’re all the same, but we are different, you know? And it’s not just that like one, you know, that one type of transgender individual, because when speaking to my family or friends about it, they have that one view of what a trans person is supposed to look like. In Trans Boxing there are all different kinds of people—just like you see varieties of cisgender individuals in other spaces. It just feels more like a community of, you know, all shades of colors, which is the kind of community I prefer to be in.

Camden Zyler (TB): What I’ve noticed about myself is that I’d rather bond with people doing activities that I like. So I feel like Trans Boxing encompasses that because I’m hanging out with people that I can relate to, and also we’re bonding over an activity that we all enjoy.

Nolan Hanson: I’ve never felt great in spaces where the only thing bringing people together was an identifier, and like, thinking that is enough to create community.

Camden (TB): Yeah, I feel like the way that systematic oppression affects gender non-conforming people or transgender people could be similar, but within these categories there are experiences that interact with our transness or our gender non-conforming-ness. So to have this one unifying thing, like, okay, we’re all equal because we’re all like trans or gender non-conforming… I personally find that like, that’s not true; there are just so many different factors. And maybe there’s a collective joy and sorrow and all these different things that we may or may not share, being trans and gender non-conforming, but we also have different interests.

Eleadah (TB): I think it’s cool to think about what we do in Trans Boxing within the wider context of boxing. Because while it is like, you know, heavily masculinized, and patriarchal or whatever, there’s a connection that’s also existing outside of that, because it is skill-based, legacy based. It’s a two-way interaction and educational kind of thing. So even if you’re the manliest of men, you have to submit at a certain point to learn everything that you need to learn. And then at some point you’re going to be tapped to give that back. To you know, be a nurturer in a way to someone else’s skill.

Maggie (TB): You’re like, you’re blowing my mind every time you speak; I’d never thought of it like that. It’s a very intimate sport in a lot of ways that I like—in the sense of like, it’s one-on-one, but then also the emotional aspect is so super interesting.

Belen Murray (PSU): I just want to say that I find it really interesting that you guys are boxers. And I’m thinking of boxing as like, you know, rough and tough, like smashing faces and stuff like that. Anyway, like, all of you are like, “Oh, it’s so healing. And it’s such a great community.” And I’m, like, “Wow, that’s cool. That’s interesting.” I need that. You know, I want to work on my self esteem and build a community. It’s wonderful [the project] it’s doing that.

Nolan: I’m glad that we can kind of complicate that stereotype for you, Belen.

Belen (PSU): Yeah among everything else!

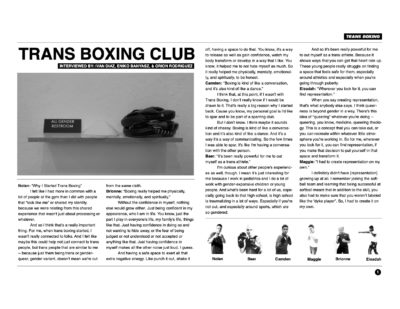

Trans Boxing Poster, by Ivan Diaz, Eniko Banyasz, and Orion Rodriguez, March 2021.

Nolan Hanson (they/he) is an artist based in New York City. Their practice includes independent work as well as collaborative socially engaged projects. Their work has been shown in New York, Chicago, Portland, and San Francisco. Nolan is the founder of Trans Boxing, an art project in the form of a boxing club that centers trans and gender variant people.

Eniko Banyasz (they/them, she/her) is an illustrator, character designer, hobby comic artist and plush craft/toy design enthusiast based in Portland, Oregon. Eniko is the owner of Pangokin Creations, and is currently pursuing their BA in Art Practice at Portland State University.

Orion Rodriguez (he/they) is an author and editor of educational nonfiction and fiction with a social justice bent. His writing has been published in Salon, Prism Reports, Lightspeed Magazine, and other publications. Their visual art has appeared in group exhibitions in Chicago, Denver, and Portland.

Belen Murray (she/her) is a graphic designer and humanities and sociology student from the California Bay Area. Belen is passionate about working with Native American communities. She currently resides in Portland, Oregon, and attends Portland State University.

Dane Kelley (they/them) is a painter and illustrator based in Portland, Oregon. They are in their final year at Portland State University and will be graduating with a BS in Art Practice. Their work focuses on blurring the lines of gender and sexuality representation by using a queer lens.

Mai Ide (she/her) is a Japanese American, Portland-based female artist, mother, wife, and full-time BFA student. Her work has been grounded in the textile realm for a long time and she tries to discover new materials as her medium. For her, an assemblage sculpture is a unique collision, an opportunity to provoke radical social change.

Ivan Vincent Santos Diaz (he/him) is an artist and designer based in Portland, Oregon. He is a full-time dog caretaker with a passion as a hobby to become a professional pitbull, boxer, and Brazilian Dogo breeder, as well as someone who has the power to reach out to queer couples and queer community, as he likes to help out with any problems.

Brianna Graw (she/her) is based in Portland, Oregon. She will be graduating with her degree in art and literature in spring 2021. She prefers to spend her time surfing, wandering, or reading a good story.

Eleadah Clack (she/her/boss) is a writer and fundraiser living in Washington, DC. She is author of The World Without Racism, a self-help guide for white culture. Find out more at www.theworldwithoutracism.com and follow at @theworldwithoutracism.

Maggie Walsh (she/they) is a genderqueer marketing strategist living in Brooklyn. They have been boxing with Trans Boxing for 2 years. Their other interests include photography, ice cream, and hanging out with their chihuahua, Puck.

Baer Karrington (they/them/their, elle/le in Spansh) is a genderqueer-transfemme 4th year medical student going into pediatrics. Their main research interest is in transgender and gender expansive health equity and empowerment, with a focus on community participatory and community-led projects.

Brionne Davis (he/him) is a Queens native trans guy who has been a member of the Trans Boxing Collective around 3 years. An aspiring entrepreneur who enjoys all things tech, tech repairs and health/fitness.

Camden Zyler (they/he) is a non-binary transmasculine bookworm and writer living in New York City. They are a proud Trans Boxing member. His hobbies include reading, boxing, learning American Sign Language, and being in nature.

A City of Newcomers

“We’re participants in a big experiment of our own devising simply by living here, much more than we are engaged somehow in creating utopian communities or ideals.”

– Ethan Seltzer

As I grappled to understand Portland, Oregon, the city in which I was new (I moved from my hometown for the first time to attend an MFA program) and everything else seemed fresh but firmly rooted, I read, on assignment, a chapter from Tom Finkelpearl’s What We Made. In this chapter, artist and educator Harrell Fletcher and Ethan Seltzer, an expert in land use planning and urban development, discuss Portland in a way that made it familiar and exciting. I was struck by the tenderness with which Seltzer described the culture and history of the city. Wanting to hear more, I asked Fletcher, whom I luckily already knew, to introduce me to Seltzer. After a brief back and forth on email to set a time to talk, we met over Zoom and had the conversation you are about to read.

Caryn Aasness: I moved here recently so some of my questions are going to be more about moving to a new city and getting to know Portland, but I’m interested in your specific point of view on that, based on the work that you’ve done.

Ethan Seltzer: Yeah, you know, Portland has been and continues to be a city of newcomers. You’re not alone.

Caryn: If you moved to a new city, how would you go about getting to know that place?

Ethan: Really good question. If I wanted to get to know a place I guess I would do a couple of things. First of all, I’d find things in the community that I cared about. And I’d volunteer. I would get involved without any expectation of profit or position. Just to meet people, and meet people who care about the same things that I care about. Because I think so much about getting to know a place is done through the people that you get to know. It’s a profoundly social kind of experience, so I guess I’d start by thinking about the things that I care about the most, and then look for places where I could volunteer, where I could get engaged, where something could happen.

Second thing I would do is, I would learn as much as I could about the history of the place. I would figure out who the local historians are. There are local historians in every community. Some of them are more formally oriented and trained and anointed as historians; they self-identify as historians. Some people are just simply the people in the community who know about the community. And I’d seek out the stuff that those people, the formal historians, had written. I basically find ways to get to know other people who are kind of local historic experts. And you can call up anybody, and the worst thing they’ll say is they’re too busy, No one’s ever died from trying to make an appointment with somebody, so it’s like I would do a little ethnography, right, and use that as a way of learning as much history about a place as I could.

And then for me, I guess the third thing that I would care about a lot would be nature. What’s the natural history of the place, what’s the ecology in the place? And then I guess the last thing I would look for over time is— I think it’s really helpful to kind of develop your own rituals in place. Like here in Portland in October, people go out to Oxbow Park and watch the salmon spawn. Or find a group of people to have Thanksgiving with and have Thanksgiving with them every year, or choose some other holiday, Solstice if you like. Find something to celebrate with other people. And do it again and again.

Caryn: If someone moved to this city, how would you recommend that they get to know Portland specifically?

Ethan: It’s really interesting. [I would want to know] what brought that person to Portland. I would poke around a little bit first with that person to figure out why they are here, what do they care about, what about this place can reward the things that they are most interested in or feel most passionate about? Because I think there are a lot of different aspects to Portland, some of which I don’t pay much attention to and other people value very highly, and other things which I pay a lot of attention to, but I’m not sure many other people care about, so it’s hard to say.

But I guess what I would start with is I would say, Read some books by Carl Abbott— he’s an historian. I would say, Get on your bike and go find some local parks. I would say, Figure out how the TriMet system works, and use it as much as you can. I would say, Make a point of going to farmers’ markets and seeing what gets grown and talk to the people who are selling, ask what’s for sale and ask them where they’re from and get acquainted with what’s coming in and out of the community. And I would say, Pay attention to local community scale festivals and exhibitions and attend, show up. I think the hardest thing in going to a new place is that you’re constantly putting yourself out there, you know, and it can feel a little relentless or a little unending or something like that, but you’ve just got to get out the front door and see who’s out there. There’s no other substitute.

Caryn: What’s like maybe one thing about the history of Portland that is compelling to you?

Ethan: One thing about the history of Portland that is compelling— well I think one of the things that’s important to keep in mind about Portland aside from the fact that we are and have been a city of newcomers— I’d add two other things to that. So it’s not one but it’s like two other things. The first is that this is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in North America. It’s been a really good place for people to live for over 12,000 years. And, as a consequence, there’s two aspects that are really important. Number one is, our personal presence here is just a blip in the timescale of people living in this place. The second is, this is a very, very abundant landscape. This has been a place that’s provided people with a good home for a long time. Pay attention to why that’s true.

But the second thing I would add to that is that Portland is a land of small things, which is to say that we do things in little tiny bits and pieces. Property here is divided up into very small units. In Arizona, or Texas, you know suburban subdivisions might have 5000 units. In Portland, a big subdivision might have 50 units. We don’t have many enormous employers, and the biggest employer in the state of Oregon, I think, is still Intel, which has less than 20,000 employees. But you know, Boeing up in Seattle has 75,000 employees. So we do things in little tiny bites. Organizations are small, jurisdictions are small. We use the term city really loosely around here. The City of Portland is a city; it has 640,000 people. It’s pretty big actually, but Johnson City is a city and Johnson City, which is out by Clackamas Town Center, has about 450 people in a trailer park. Both of those are regarded as cities in the context of things. So we’re a land of small things, we’re a time deep land, and we’re a land of newcomers. And I think those three things are important to keep in mind.

Caryn: Where in the city are you most aware of city planning or land use planning?

Ethan: Well, I spend a lot of time trying to understand land use planning at a pretty granular level, so it’s kind of like, when I look out at the city and I look out the window of my house here. I mean I see a lot of different stuff, right. So planning to me is kind of evident everywhere and if not planning, certainly the decisions people have made at various points in time. There’s a book by John Stilgoe called Outside Lies Magic, which is just kind of a story about what he thinks about as he walks around outside. And Stilgoe is a landscape historian. And this is kind of a book that was inspired by his work with his students, and ways of getting them to think about what they were seeing when they saw it. But there are a couple of things that I really think are kind of essential parts of Portland’s planning history.

Every structure, every neighborhood, every part of the city, whether you’re talking about Northeast Portland and redlining or Chinatown, or the east side versus the west side, there’s all kinds of history embodied in the structure of the city. But from a planning point of view, I think, two of the plans that have been most important to me have been the 1972 Downtown Plan, which is the reason why a lot of what you see in central Portland in particular is what you see in central Portland, I mean it really happened. And in a profound way, in a way that set Portland apart from other cities, which is really really interesting. And then the other one that is really important to me is the Urban Growth Boundary, which is a way of recognizing the kind of profound and irreversible impact of urban development and urbanization and urban land markets on rural and natural land resources. The Urban Growth Boundary is proven to be maybe the only effective tool at really enabling places like Portland to manage growth.

Caryn: One big old question. Do you think about utopias?

Ethan: Oh, fun question. So utopias are pretty interesting because in every utopia, there’s an element of dystopia. Right. And so, I don’t think a lot about utopias. To be honest, I’m less interested in what the perfect arrangement among people is than I am with what we can learn from the relationships between people and each other and people in the places they’re in. So to me, you know again back to the notion that we’re in this place, but this place got a 12,000 year headstart on us, basically. So what we’re doing now is really part of a long, ongoing experiment. Our legacy is not streets and roads and buildings, it’s how those streets and roads and buildings intervened in this place we found, and that will be found by others after us. So I look at it more as, you know, we’re participants in a big experiment of our own devising simply by living here, much more than we are engaged somehow in creating utopian communities or ideals. Yeah, have you ever read the book Ecotopia?

Caryn: No.

Ethan: Okay, Ernest Callenbach, nineteen seventy…I don’t know, six or something like that. It was kind of a description of Northern California, Oregon and Washington, breaking free from the United States and creating Ecotopia. Yeah. Check it out.

Caryn: Is there a book or movie or TV show that gets Portland right?

Ethan: Well, there was a movie back in the ‘70s called Property by Penny Allen, it was about hippies and gentrification. I think that’s pretty interesting. That was kind of fun. Let’s see, what else has been a good book…I don’t know, I’m trying to think. Yeah, I think certain parts of Ecotopia kind of get some things right, or did once upon a time, anyway. But I think if you are interested in writing a book, there’s room for a better book.

Caryn: Do you have any final thoughts?

Ethan: Well, tell me a little bit about the work you want to do.

Caryn: There’s a lot of things I guess, but I’m interested in getting to know this place in as many ways as I can because I’ve only ever lived in one other place and so it’s a brand new experience not only to be here but just to be somewhere new. And especially moving during quarantine. I feel like the way that I’ve been getting to know this place is through Craigslist ads, or just looking at the maps. It’s interesting to try to grab as many little pieces of the culture and the history and all of that from mostly being inside and on the internet.

Ethan: Yeah. Right, exactly. Because I mean so much of what we’re talking about is so tactile, isn’t it? Smelling things; it’s the sensual experience of a place really. One of my favorite definitions of urban design is the management of the sensual experience of the city. So it’s the breeze on your skin, what you smell, what you see, what you hear. It’s kind of the engagement of the senses, and in many ways it’s about creating environments that are much more successful at engaging the senses than we often find in the most urban places— it’s very much part of getting to know a place. Absolutely. I mean, I hope you get a chance to try swimming in different places to see how they’re different— you know, swimming in the Columbia and the Willamette and swimming in lakes, on mountains and other rivers and seeing what that’s all about. Hagg Lake, for example, out by Forest Grove, is this largely rain-fed lake. The water is incredibly soft. It’s amazing. Yeah, it’s really great. So when it gets hot and you’re looking for swimming, go try Hagg Lake sometime.

Ethan Seltzer (he/him) moved to Portland in 1980. He is now retired and has worked in the city in a number of capacities including as a land use supervisor. His roles at Portland State University included being the Founding Director of the Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies, the Director of the School of Urban Planning and the Director of the School of Art and Design. He has held jobs in the nonprofit sector and has volunteered widely.

Caryn Aasness (they/them) moved to Portland in 2020. They are a graduate student in the Art and Social Practice MFA program at Portland State University and are still trying to figure out the city.

On the Other Side of the Fence

“If something doesn’t quite seem right, your eye will fall on it… Because it’s a pattern that’s totally different from the pattern you expect to see.”

– Danielle Moser

Three years ago, I moved to a rented home close to Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania. There are many histories that shaped this land, but in the context of this interview, I focus on the more recent agricultural practices that now dominate the surrounding landscape. The Dickinson College Farm is my next door neighbor.

In what started as serendipity, I have been on lamb-watch and sometimes bottle-feeding duty on the farm for the past two spring seasons. A vastly under-skilled but convenient choice for this role, I jumped into it. A portion of my artwork involves fibers, textiles, and textile-related processes, so this was a new link in the fiber supply chain to explore. Following this initial interest, the lambs became part of a ritual I perform while air warms and soil thaws. I jump over the fence to check on members of the flock, look for new or struggling lambs, and bottle-feed with warm milk formula. The process offers clarity through repeated tasks meant to sustain a life—efforts that aren’t always successful. Later, during this ongoing period of global mourning, working with the lambs remains a way to navigate survival, loss, and care. Having never spent much time with livestock before this, my concern has expanded from a personal realm into something more communal: specifically, I wonder how this experience resonates among members of my community for whom agriculture is a way of life. Symbiosis is a spectrum, and exploring agricultural relationships can make the complexity of interconnection more visible.

Originally, I got to know Danielle, a livestock apprentice, artist and aspiring veterinarian, by name and not by face—she was another person caring for the sheep. Time with other people in the pastures is limited, especially now during the pandemic. Even so, the act of caring for these animals feels like social dialogue. Lamb feeding instructions come in the form of text messages, notes left on kitchen counters, unfamiliar tools, empty soda bottles, and plastic numbers on tiny, floppy ears. The following conversation is an initial survey of ideas that come to mind when I examine this work, along with potential connections to expand upon.

The two of us spoke while walking around Carlisle, PA, where Danielle lives. It’s a fifteen minute drive north of Boiling Springs and the farm.

Mo Geiger: So I was thinking the other day—the lambs are going to kind of book-end COVID, which is a crazy thing.

Danielle Moser: True, right? Hopefully.

Mo: Yeah, and it might continue, obviously, will probably continue. I was wondering if, in caring for animals on the farm, you think about time differently?

Danielle: I think it works almost, at least for me, in the same exact way as it will probably work for Will (the farm’s vegetable manager) and people in vegetable production. When you’re working with animal husbandry and there’s a reproductive cycle to keep track of, that totally influences the concept of a year. Seeing the year in terms of seasonality is so different, the more I’ve worked with animals. Working with the reproductive cycle as a career, definitely, you start thinking of time differently in that way. And with the lambs: the time, really the timing, can be so important, as we’ve seen before: you mis-time [things], then you suffer and your animals suffer.

Mo: Right.

Danielle: You know, Will might think of July and think of whatever vegetable he’s putting in the ground. I think of July and think, maybe we’ll probably be done calving by then.

Mo: Can you talk a little bit about what brought you to farms or to livestock? How would you trace that in your own life?

Danielle: Sure. Yeah, in my case, my only farming history is that my mom grew up in Lancaster [Pennsylvania]. And so whenever we’d visit my grandparents, we’d always be driving through the farms. My mom was always involved in Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) stuff when we were younger, so I also had that kind of knowledge that such a thing existed. Then, I started volunteering at [animal] shelters and got interested in veterinary medicine. And everyone I talked to was like, oh yeah, sure, small animal vet, but you should really look into being a food animal vet, because that’s what we need right now. Everyone’s always talking about the deficit in food animal expertise. Then, I was studying chemistry, [and] at that point, I was like, I don’t think I’ll probably be a vet. Got interested again, and that was a big reason why I came to Dickinson and then just found that I preferred working with the sheep and cattle.

Mo: You make artworks in addition to farming and raising livestock. Can you describe that connection?

Danielle: I think part of my interest in medicine is because it’s so visual. Farming, for me at least—I definitely see it as a visual thing. And observing these animals, observing their anatomy. For example, one time I did a camp. It was a session of going to University of Penn’s small animal hospital and touring the pathology lab. And the veterinarian showed a slide of a tissue sample. And I was looking at it as a piece of art. I was like, This is the coolest thing I’ve ever seen! Some of the visual anatomy and stuff like that. And even, you know, when you see a butchering done—I mean, the act of butchering I’m not particularly attached to, I’m still a vegetarian—there’s a lot to be explored there.

Mo: And you have kind of a kinship with the sheep, right?

Danielle: Yeah. And chickens. We got chickens when I was in high school, which got me interested in veterinary medicine in that way again too, because well, their anatomy is really cool, but I also just got such a kick out of their personalities and practicality.

Mo: Do you feel like while you were learning how to take care of livestock animals, that you had already done some of that physical learning beforehand? Or did it feel like a new process?

Danielle: I’d say a new process. Because that’s what it is with every animal we work with. It’s just so weird to conceive [of the fact] that these animals eat grass, or hay or something, when you’re so used to kibble, or wet food, or whatever. When it’s time for the animal to eat, and you chuck in a bale of hay—it’s definitely a change.

Mo: Right.

Danielle: This is a contention that I have with a lot of people who say that cows are just big dogs, or that horses are just big dogs. They’re just so different. And that changes the way you check if there’s a problem. Like—are they behaving normally for that species? If your dog is being more fearful than usual, they might have an injury, right? But if you look at a cow that way, if the cow runs away when there’s a loud noise, it’s because it’s a prey animal—that’s what they do. So, noticing behavioral changes, seeing what’s normal versus what’s not, that’s definitely a totally different thing, too. I’d argue that recognizing those discrepancies in behavior, or overall state, definitely is an everyday part of taking care of them. Checking to see: are they all ok, is anyone sticking out? Because you don’t want that, for sure.

Mo: So there’s an element of looking at the individual and looking at the group at once?

Danielle: It’s a lot of, at least for me, I’ve always enjoyed trying to see… You know, like those pictures where you have to search and find what’s different from the two pictures? Yeah, I always liked that kind of thing. Or doing jigsaw puzzles. And, when you check on the animals, if something pops out at you, you look closer. Because this individual that’s kind of making themselves obvious in a way—there might be something that’s abnormal.

Mo: So, you’re kind of constantly searching for changes. Does that describe the process?

Danielle: Yeah, or just… like almost errors in a pattern, you know?

Mo: Oh, that’s so interesting. Yeah.

Danielle: If something doesn’t quite seem right, your eye will fall on it. So if there’s an animal that is limping, you fall on it pretty quickly. Because it’s a pattern that’s totally different from the pattern you expect to see.

Mo: Has taking care of animals and looking for patterns in that way changed the way you interact with people? Or does it change your observation in worlds where animals aren’t around?

Danielle: It’s definitely influenced my own understanding of my ability to do that. And recognizing that as kind of like a skill, or something like that. It’s hard to say. I think a lot of people get into taking care of animals because maybe they don’t read humans well, or, as well. Taking that knowledge and applying it to humans isn’t something that I’ve done, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it can’t be done.

Mo: Sure, sure. And I wonder too, because I do work with textiles, there’s this preconception that the concept of care is playing a role, and there’s this feminine exploration happening. And sometimes I think care is [seen as being] limited to that scope: a delicate, care-ful sort of thing. I wonder if you, in your experience, have had to deal with that idea.

Danielle: Like the femininity attached to the nurturing aspect of animals?

Mo: Yeah.

Danielle: Yeah, I’d say I definitely relate to the nurturing. I don’t always relate to the female aspects. But that’s just me as an individual. When I was trying to visit a farm to come out and do some work for them, the one person who I knew had worked with them before was like, Oh, yeah, she only likes women to come by, because men go about livestock in a different way. So in some ways, the women in livestock may be stronger [workers] because of that attachment and nurturing things. Or if such a relationship exists, it might exist in some people, and their female identity has influenced their nurturing interest.

Mo: So that comes up? The gender difference?

Danielle: Yeah, and the whole gender difference thing can really mess you up if you’re trying to find opportunities with some more conservative, male livestock people. And that goes back to stereotypes of you know, women getting overinvested or physical strength being a barrier. I was warned by a veterinarian on both being a woman and being young: “You’re going to encounter difficulties.”

Mo: And then wanting to work with large animals. Yes, right.

Danielle: But it’s funny because you think, [in] livestock animal husbandry, so much of the emphasis—or basically all of it—is on the female animals.

Mo: Yeah!

Danielle: That sexuality is so inherent to it. And yet, it’s dominated by men who, you know…

Mo: Who actively exclude women for these preconceived reasons.

Danielle: Yeah. So I wonder if [the bias] has an aspect of preserving your, you know…

Mo: [Laughs] Vessel-like nature?

Danielle: Exactly. And if they view animals solely through their reproductive capacity, I wonder if that influences how they’re going to view a woman. Just on that basis.

Mo: So, this pandemic is happening, and we’re surrounded by an awareness of life cycles and death in a way that I don’t think, um, the vast majority of people expected…

Danielle: [People] who are outside of farms?

Mo: Yeah! and that’s a huge part of raising anything on a farm, right? This constant awareness of death and life cycles? And now, more people feel that in a way that’s not always been so obvious.

Danielle: So going back to some of the really conservative people and livestock… [They] will put a lot of work into saving an animal, and when the animal doesn’t make it, they’ll say, “The Lord decides when it’s their time to go. He takes them.” And I’ve heard some of this used by people in regards to anti-masking. In the really conservative spheres that don’t want to wear masks, they will be like, “Oh, if the Lord wants us to get COVID, we’ll get COVID. And if it’s our time to go, we’ll go.” [I am] seeing that kind of selective attachment—or dis-attachment—to life and value in that way. Or, chalking it up to fate, or a higher power. I’ve given some thought to the way that conservatives view life and death in that way, how they’ve applied it to COVID, and losing animals.

Mo: I wonder too, if there are things that can be dug up from the knowledge of raising livestock. Are there things to take away from this experience that we’ve all had over the last year, and what are the connections?

Danielle: Unfortunately, I think in some ways, there’s a connection that can be made absolutely with the divide in the country.

Mo: Right. Because this kind of care is becoming so distant from people—it’s not so much in front of our faces— it’s happening behind the scenes to a certain extent. Has the idea of care changed as a result?

Danielle: As a result of COVID?

Mo: Well, and also everything that led up to it. You know, economies pushing our awareness of raising animals further and further to the edges.

Danielle: Right. I mean, it’s funny, because I feel like a lot of small farms: smaller, sustainable ag farms… Business-wise, they might have done a little bit better than usual. I think that was solely because of the interruption of supply chains. Which is entirely a result of economic stuff.

When you interrupt the status quo [and] shake it up a bit, what tumbles out? You definitely look at it differently. What’s left behind? What survives?

Mo: Being a vegetarian and participating in this kind of relationship building—does pursuing a relationship [with food animals] feel ancient? Like: this is the only way to have that kind of relationship today?

Danielle: You said, does it feel ancient?

Mo: Yeah.

Danielle: It’s super interesting that you said that. The one time where I felt like I kind of understood, a little bit more, the connection that you can have with an animal and yet still do this thing, too, was when Hamid came to the farm. He lives in Lancaster; he’s an Arab Israeli who came to the U.S. His family—they have a shawarma stand. He does a lot of meat stuff, particularly with lamb and mutton. First of all, the method: they exsanguinate, [but] they don’t stun or anything. And I’m the most secular person I know, but in some ways, I think religion is the perfect way to bridge that gap. There’s so much imagery around harvesting animals, and lambs. Sheep are so common in the Bible and the Qur’an. So many ancient texts describe the relationship between humans and sheep.

Mo: Yeah.

Danielle: He opened up the actual process with, first of all, he was insistent that no one take pictures. Because it was a sacred thing. Which Matt (the farm’s livestock manager) requested as well, the one time I saw a sheep harvest before this.

Mo: Yeah, you’re watching a death.

Danielle: Right. And it’s like… to document that with pictures… I don’t know. I’ve gotten into debates about it with other people who are like, if you can’t take a picture, should it exist? But he also prefaced it with: “This animal is a gift from God, and we are telling God that we accept his gift.” Maybe it was his sincerity that was palpable, but I thought that was a really cool perspective to have.

Mo: Yes.

Danielle: And it’s clear that there’s an attachment between [human and animal] as well, right? A “care.” But ultimately, consumption. In some ways, I’m jealous that I can’t quite practice religion in that way. I kind of severed my ties a long time ago.

Mo: I have a similar relationship with religion: [being] somewhat in awe of its power to be able to do that kind of thing. But having shed it many years ago, it’s kind of interesting to be able to have that separation, where maybe you can observe how it can be practiced that way.

Danielle: Right. To have it without any sort of lens. But then again, a secular perspective can be seen as a lens, too.

Mo: I guess it’s all lenses.

Danielle: Yeah. Gotta have bifocals, I guess.

Mo Geiger (she/her) is an interdisciplinary artist and graduate student in Art+Social Practice at Portland State University. See more of her work at mogeiger.com.

Danielle Moser (she/her) is a second-year Livestock Apprentice at the Dickinson College Farm in Boiling Springs, PA. She is also an artist and aspiring veterinarian in food animal medicine. See more of her work here.

Becoming Black

“I began directing my attention, both what I was studying and who I was working with and for, in a specifically Black direction. And it is that kind of moment where I began to really strongly interrogate my own Blackness.”

Master Artist Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr.

I have been having a series of conversations with Master Artist Michael on the topic of our practices and race for some time now. I decided to interview them for this issue of SoFA journal’s Conversations On Everything to ask more about their personal history of reclaiming their past, and making space in the future for kids to move towards and flourish into a better society. Being a part of the African diaspora myself, I do not know much about my real last name due to generational trauma, and half of my family history has sometimes been difficult to grab a hold of. Talking with Master Artist Michael about their longing to find and reclaim their identity in their history, and pave a way for kids, inspires me deeply. They are making very important work in discussing the power in embodied history and sharing that embodied history. In this interview, I think a lot about time—how we do not have control over time unless we are archiving, documenting, educating, storytelling and sharing, as well as considering our own agency, and giving ourselves permission to take power.

Michael’s work, Afro Contemporary Art Class (ACAC) at KSMoCA (King School Museum of Contemporary Art), as well as the Afro Contemporary Art Archive in Special Collections at the Portland State University (PSU) Library, are spaces for archiving, documenting, and collective storytelling. Michael states, “ACAC (referring to both projects) helps young people of African descent to learn more about the histories and contemporary contexts that shape their lives, culture, and social contexts. These ideas are explored by studying contemporary artists and creatives as a conduit to (and a lens for) thinking through a range of experiences related to the African diaspora.” I hope you enjoy this interview with Michael. I recommend checking out a recent book I am reading called One Drop by Yaba Blay, on the range of experiences and identities in the African diaspora.

Brianna Ortega: So a couple months ago this Instagram account reached out to me and they’re like, Oh, we wanted to reach out to you. They said they were talking about my project and said to themselves, How did Bri know that Black Lives Matter was going to happen? How did she know to have Black Lives Matter in her second issue (of her surf publication)? And she had Black people. How did she know?

And I just was like, What the heck? It was so bad. It was horrible.

Artist Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr.: It’s an interesting time. People haven’t had to even think about this stuff. And yeah, I mean, it’s also weird. I made a post on Instagram recently and people said, Wow, great words. But my words didn’t feel overly profound to me. But, people are just literally like getting started, you know? Um, I mean, do you know about Adrian?

Brianna: I love Adrian Piper.

Michael: Yeah. So, I mean, she, that card was that project. She did the business cards, so it was like, Oh, by the way, I’m Black fucking you.

Brianna: I appreciate always talking to you, Michael.

Michael: Well, I also enjoy the university space with you.

Brianna: I feel like we’re both really, really different and that’s interesting.

Michael: Indeed.

Brianna: I know our last conversation we had was like in November and then I was driving up on a surf trip to a remote location. We were kind of just breaking down your identity as a Black man and your journey with that. Through the process of contextualizing your work over time, how do you identify yourself, or how has your identity changed through the making of your work? Like over the last few years, and since you started your work Becoming Black?

Michael: Sure. It was interesting that you specified just the past few years, because I do think a major change has occurred in this short time, though also has it been a longer process. Part of the container of the longer process is like my identity is now Master Artist Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr., which has changed recently. But I have been seen as Artist Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr. for a very long time and I was Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr. before that.

People might ask me, That’s your name? No one identifies as their full name. In fact, some people abbreviated or changed their names. The first stage of identity shifting was talking about objects, my origin as an object maker, and this culture around generating an object and then signing it with your name. “What is the culture of your signature?” is interesting as well because being in a—it was not just an object culture—but specifically was very near to like glass ceramics, and maybe even more influenced by glass culture.

One of my professors said, Yeah, when I was coming up, everyone’s like, Oh, sign your name real big. It was a big kind of ego thing, you know, even as it dates back to Duchamp, and the fact that there’s this expectation that you are signing your work and it may even be in an image taken of it, you know, ruining the image to include your name. My professor said, You guys don’t even sign your work, I don’t get it. So I thought, What’s my artist’s name? And I didn’t really identify with Bernard.

And it’s funny, I got a star chart reading right when I moved to Portland on the first social practice camping trip, and then Renee Sills who did my reading said, Oh, you have problems with identity. I thought, Well, this is working.

I decided to identify as my father’s full name sake. Right? He bestowed that upon me and it goes even further. It is this interesting, subtle cultural piece that has really sharpened in the past couple of years. I remember vividly. I found it on the internet. There’s this audiobook called Gift of the Tortoise. And it was like an African cultural thing. I was a young kid, and my mom got it for me, for whatever reasons she might’ve had for getting it. There was a song. The drawing on the cover was like this anthropomorphized turtle woman. The narrator on this album described the surname family name situation, and how when people would travel and go to like a different village, they would introduce themselves and they would say their entire family. From a very young age I thought about my identity. But, just thinking back now, since choosing to identify as my full whole name, I realized how there is a kind of cultural history that’s lost in the ways you choose to identify or not identify yourself through your name.

Now, I’m changing my name and my pronouns. And I’m shifting everything that was given because I want to reject it. I was always also attracted to indigenous cultures or other cultures where you earn a second name based on who you are. And so me claiming my father’s name is kind of like this version of that version for me.

I’m also an artist and artists are marginalized in ways. And I also want to be able to show up and [have it] be like, Oh, this is the artist. And you know, doctors get like a prefix of notoriety in general, or Mr. President…these things that we’ve decided as a culture to give power to. And Artist is not one of them. You might happen to be able to work your name into a Picasso or Vincent van Gogh. But not Artists as a culture or a group or an identity. And so I was like, I want all this on my name. I want my cultural group. I’m like forcibly marginalizing myself, like whatever. And then it became in pursuit of Master. During the in-between arc of pursuing mastership and post-school, I realized that Michael is an Archangel name. So it’s like Christian. Bernard is a Germanic name—in the distant past, but even prior to World War II, Germanic culture was colonial. They were essentially a war-based nation that would take stuff from other people. Stevenson is a Eurocentric name structure. So it’s essentially linked to the Mayflower coming to the Americas, and then introducing this kind of name structure.

And so here I am, an American citizen born to a Black man and an Italian woman, and all of my names are colonial names.

There’s this kind of pretentiousness projected onto me. And so I’ve started to explain it in more detail because I’m like, this is why I’m doing this. This is my own project. Like, this has nothing to do with you and you could choose to be an Artist as well. And it’s also interesting because with the shift to Master Artist, I am now a part of an even more select group, like not infinitely select, but more select than just Artist. PSU won’t let me use my chosen name, which is also interesting because there’s so much contextualizing I’m doing in my work and have signed my checks with Artist Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr. I started to sign them Master Bernard, you know, and my roommate is also someone who has a fiscal relationship with me and has paid me as Master Bernard.

I have like a paper trail, you know, with this identity. And PSU asks, What about your birth certificate? And I’m like, Okay, so you’re now preventing me from doing this, this is the whole point of it, right? There are these colonial systems that will tell me who I am and what I can do. And this is just another example. I’m going to get a stamp made that says Master Artist and alter my diploma. And now this pertains to other people, like anyone—you will be able to use this Master Artist stamp to identify yourself. And it can be used by anyone, even a child.

All of my names are not any of my ancestral cultures. There are these cultural identities battling to claim certain historical contexts within our species. And Black always remains on the bottom and is actually the foundation for all things in many cases. And so I use conversation around my name and essentially at this point, it doesn’t actually matter where it’s from. I’ve claimed it. And I’m now making it my own. Regarding some of your initial questions, Becoming Black and these other things, choosing what my identity is myself is this form of power that I have that both denies and is within awareness of something’s original place. Claiming it and making it my own, which is, pinging the sentiment of Becoming Black, not forgetting I was born Black. Depending on who you are, or at least in people in our situation, whereby you’re white passing, it’s something you have to own, otherwise it is invisibilized for you or you learn to invisiblize it, which I don’t think is inherently problematic. Maybe there’s a million reasons why someone might want to invisibilize themselves, however the primary reason is ostracization. And because of ostracization, there’s a desire to distance. Born from something that they don’t feel good about, that part of themselves.

But to bring my original identification into my current life—I don’t remember being aware of the process of Becoming Black again. I think it began a little while before I even started authentically investing in it as a project and making decisions based on it. But what is the precursor to all of that was starting the Afro Contemporary Art Class.

Brianna: How did you start the Afro Contemporary Art Class?

Michael: I met someone at the Headlands Center for the Arts who said I should look into the Black School and some other kinds of extracurricular groups that were specifically taking Black culture and Black history and turning it into a lesson that could be inserted into schools. It was that conversation that had me transition my graduate project into Afro Contemporary Art Class from maybe just sculpture class at King School.

An original intention for that class was to teach young kids the entirety of Black history, and then use that lesson, where we look at the history of Black culture, to then look at Black art.

Nyame Brown is an Afrofuturist painter with a robust career that we studied in the class. With the ACAC, I’ve been able to choose the artists whose work I want to contextualize into the lives of young people, and for that reason I was interested in Nyame’s work because it features ideas young people are already thinking through. Like the comic book character, Black Panther, and Nyame’s self imagined Afrofuturist character who I believe he calls Panther 13.

They’re working with all different forms of symbolism. Like in one of his paintings, there’s two characters and the first is writing C.R.E.A.M. on the second one’s back. And that acronym is colloquially “Cash Rules Everything Around Me,” which is the title to a Wu Tang Clan song. And, you know, meanwhile, he’s also inspired by Shakespearian contexts and kind of like a Pan-African Indigeneity. He’s marrying all these things together.

The original intention for the Afro Contemporary Art Class was to have studied every aspect of Black culture and history chronologically. Once we began to look at Nyame Brown’s paintings the project kind of transformed into looking at an artist’s work and then drawing out the history visible in the work before talking through and learning about that.

And so my point for both [Black culture and art] is that in neither circumstance did I actually consider myself to be educated, in a way where I could teach it. So I began to educate myself on all of these different things. And that is what kind of opened the door, because like what you and I have discussed in the past and kind of are discussing now, there’s a specificity around Black culture.

Brianna: Can you share a little bit of your personal history?

Michael: It’s interesting because, you know, I was raised in a Black family, in a Black household, like my grandmother’s house. There’s certain parts of my existence that are foundationally Black. And as I got older, I stopped going to my grandmother’s house. I had my own friends and whatever.

And even though I was living in a multicultural community, like very diverse, there was not any kind of specificity around being Black. You know what I mean? Like in my household or in the version of history I was taught in school.

Meanwhile, in my work, with the intention of benefiting different social systems in certain populations, I was directing my own intentions towards people facing marginalized conditions, which, disproportionately, is Black, young people. I was already working with Elijah, a young person who I connected with at KSMoCA and made art with, even though my content wasn’t specifically looking for a Black audience. And then when I was getting ready for my graduate class, I was like, Oh, African Contemporary Art Class. I want the entire class to be Black students.

I began directing my attention, both what I was studying and who I was working with and for, in a specifically Black direction. And it is that kind of moment where I began to really strongly interrogate my own Blackness. Such as instances where I was in situations that were anti-Black, even though—and you were talking about like being white-passing yourself—I don’t know that I consider myself white-passing. I think I’m white-passing-ish. Which is predicated on just me literally feeling like I have white privilege. At this point I have identified, I am Black and I think I express Black and I think I participate in things in a Black way. Especially now, but always, maybe. And I think also even, there’s ways that people have perceived me or how situations have gone, where even though I actually am feeling forms of white privilege or that I can be in a white space unchallenged, other people are projecting Blackness onto me in that situation.

I’ve learnt about Black art through creating the Afro Contemporary Art Class as well as the varying things that I’ve studied—including a Black film class, working to build the Afro Contemporary Art Archive at the PSU Library as well as researching and consuming different kinds of work. It’s a spectrum of things including UPN [United Paramount Network] show Girlfriends featuring Traci Ellis Ross, daughter of Diana Ross, or, you know, different Black films from the Blaxploitation era, different artists work, or recently deceased MF Doom—which weirdly in a not-so-distant past, I was identifying with his work and his practice, and later learned he had died not long after. When I found out, I went to his web store and I saw all of their albums and other merch was sold out.

And so I think, you know, two years ago, I would have thought, Oh yeah, like another Black creative dies. Okay. Fucked up, like this happens, like when Prince died and Michael Jackson died, it catalyzed the consumption of their life in their work and therefore their lives. Like a commodity.

I just am thinking about all of these things and how they’re juxtaposed with my own identity, whether it’s something I’m choosing or is projected onto me. And I think what I was just saying about MF Doom and the consumption of life—these things are projected onto me—but there’s also things that I’ve now chosen to identify with, and/or seek out.

Becoming Black embodies all of the things that I’ve been slowly describing. It’s a way where the conversation we’re having now is different than the conversation we might’ve been having two years ago. You know, not long ago, I was even skeptical of how much I was being perceived, presenting as, or identified with Blackness or Black culture.

And that has exponentially increased. I really do feel like a part of it in a way, whereas before I felt totally outside of it. And now I don’t. But also as I sit here, I’m wearing Kente cloth pants, essentially an extension of Becoming Black, which is an identity-based project that really has no structure or form worth presenting, but can be discussed. And I have an independent receipts folder of different clothing items purchased from Black businesses that are in some way Black leaning, if not in origin, also aesthetically. I’d had a t-shirt that I purchased from a thing called Artists Untold and they might’ve been mostly POC, but it features an artist and the artist’s work, and the shirt is priced at a designer cost. The t-shirt was like a darker Black-skinned lady and a lighter Black-skinned lady just, they kind of have no nose, maybe just like mouths and lips and a little bit of neck. The lips have orange lipstick on them. I wore that shirt when I went to the Afro Contemporary Art Class.

I usually just wear stuff out of whatever, a recycling bin; a sense of fashion is forsaken even in contemplating my identity. I’m not thinking about my appearance or I’m subverting my appearance. In the very recent past, literally since the uprising, after George Flyd’s murder, I was like, I feel more Black, but I also have some sort of like white-passing power, even if it’s just like, through my lexicon and way of moving through space, people are like, Oh, this Black guy’s okay. But it’s like, I actually wanted to appear more Black. You know what I mean? And so am draping myself in explicitly Black things, not to be like, Hey everyone, look I’m Black. But to be like, I’m taking up space as a Black person.

Brianna: Thank you for sharing the whole story and everything.

Michael: Totally. I mean, this is interesting. I haven’t even really found a place. I’m like, in some ways, vaguely unresolved in my own life around it. But there’s an altercation in my family that too, for me remains, unresolved. Like I was in my grandmother’s kitchen. I think I was ready to leave the state. You know, she lives in North Carolina. I traveled there and it was just like breakfast table-style moments. She was randomly talking about standing next to a female police officer in the line to McDonald’s and that she had like all this gear on and she was really petite. The kind of gear was, you know, more impressive seeming or something. And my uncle was talking to her about it and telling the story and then my grandmother casually says like, Oh, it’s a shame that she really needs that stuff or something. And I was like, What do you mean? And she said, You know, well, she’s hanging out in the ghettos and she’s got to protect herself and whatever. And I was like, Well, what the fuck you talking about? Like, I don’t think this is true at all. And then somehow the conversation evolved. Meanwhile, again, I think this is a very interesting situation because it’s different from all the stories I’ve told so far. I wasn’t super strongly identifying with Blackness, you know what I mean? This was six years ago or something. I hadn’t, uh, militarized my identity or something.

It’s just interesting and terrible in some ways that this is my own blood. And all of these things I have are kind of these precursors to my upbringing or my own awareness. But they are also the building blocks of, you know, why am I finding myself in a K through 5 school that’s expanded to a high school, and interestingly both are the two most Black schools in Portland, right? Are we saying that I wound up there by accident? Or are we saying that I wound up there because there’s these different elements in the world or my life that have shaped this story prior to my even participating?

I vividly remember some events in high school where one of the students said, Don’t say African Americans, say Black, and that was prior to my own thoughts and feelings around it. I don’t use the term African American unless someone is self-identifying. Because otherwise it’s like, Nah, I’m not trying to just be American by accident. And I’m not trying to juxtapose my Blackness with being American either. I’m specifically claiming these certain things that continue to even grow and become enhanced contextualization.

Brianna: Can you share about your new show with Arlene Schnitzer?

Michael: I essentially reproduced the Huey P. Newton photograph, where he’s sitting in the wicker chair. His life included being shot, shooting someone, killing a cop, getting arrested, and getting released from jail.

I don’t remember which of these events was the precursor to the creation of this photograph, but one of them, it was really like a fuck you, you know what I mean? And so I’m channeling some of that similar energy thinking about structural oppression. I’m not interested in giving them Black faces, you know what I mean? And that’s sometimes what people want, like, Oh, it’s so great to see a hundred Black kids smiling and cheering and jumping rope. Like let’s put it on the cover of our magazine. I’m thinking, What the fuck are you doing? I’m doing that work. You don’t get to say I won. You say you’re supporting this. If you were supporting this, I wouldn’t be searching around for crumbs to try to do this work. And essentially the majority of my time and labor is unpaid. So I reproduced this photo with the intention of bringing these narratives closer together, both the narrative of my youth work and the narrative of my community organizing, but to give it a facing or a facade that is in ways militant. But it was interesting because when I showed the photo to my cohort, my classmate Zeph asked, Oh, what does it feel like to be embodied in history?

And said, It’s very empowering. I didn’t just play Huey P. Newton. I am in the schools. I did the Black Panther Breakfast Program. I’ve created pamphlets about anti-Black sentiments. I’m in the community. I’m contributing resources. Like it’s just a juxtaposition. It isn’t an imitation. And then this has cemented my own path for a pursuit of meaningful identity that like, This was before me, this was for me, this is who I am, and this is what I’m going to be. And this is who and how I’m going to teach.

There are these nuanced figures in history, whether it’s musicians or artists or these different activists that you know are not a part of the common narratives of who’s being celebrated. And so it’s like all of this stuff that I’ve been doing and other people have been doing—a lot of my work is even raising up the work that has been done before me. And I haven’t studied it. I didn’t get taught it and I wasn’t identifying with it until the past year and a half, two years. It is even this vivid awareness that Becoming Black as a project exists. I’m finding my own way. This wasn’t taught to me in any school. In fact, I’m creating my own school system and educational materials to be reflecting on this. And so I think Becoming Black is centered on my experience. Like what are the ways that I am having this experience? But also it is the way that I’m cultivating that for others.

Brianna: Yeah, thank you so much for sharing all that. It’s really powerful. And it’s just cool to hear your own journey through it all with your identity. I know I talked about family members being ostracized from our family due to the color of their skin.

Michael: That’s interesting too because that is a part of the colorism discourse, you know what I mean? Like it’s okay to be light-skinned Black and, you know, you get kind of invisibilized if you’re a dark-skinned Black, and you have privilege if you’re light-skinned Black.

My Italian family doesn’t know how to speak Italian specifically because my grandparents’ parents didn’t teach them how to speak Italian. And that was specifically because they were trying to assimilate. And so, kind of a white-centric colonization exists on all sides of my family. And the discourse around colorism exists strongly. You know, there’s a lot there around that. But it’s also interesting because often Black people get seduced by anti-Black sentiments and kind of reject their own identities for other stranger reasons.

I was talking to someone locally a long time ago. We were talking about some of these things and he said that like, you know, I forget exactly his wording, but essentially he was saying that the entire culture of Black people and beyond need to really reckon with the fact that all Black blood in America is mixed blood.

So you know, there’s that, and that remains invisibilized in all kinds of different ways. But yeah, like these things that we don’t know about, right. People in our families are trained to suppress their relationship to these things. And so, I mean, the world’s a different place in some ways.

Panelists: Damaris Webb, Nora Colie, Ethan Johnson, Lex Weaver, Brianna Ortega, February 2021. Image courtesy of Master Artist Michael Bernard Stevenson Jr.

And so it’s not even inherently as problematic to be examining them. During college I lived in a small town and I was working at a grocery store and I remember one day a customer and I were talking about kind of the loss of culture and he’s like, Well, just so you know, it’s always there for you.

And I remember when he said that I thought, I don’t feel like that’s true. When it’s gone, it’s gone. I didn’t have it when I was growing up and I don’t know how to get it. And it’s just gone and I can just go to Africa and they’d be like, What the fuck are you doing here? But I’ve been thinking about it more recently because of all this stuff, looking back at history, and now I’m starting to see these different parts of history that were otherwise invisible, and see myself in it. And so it is there for me to find. And so my whole point was, what I was thinking when you were talking about your dad and his kind of rejection and stuff, is that the Afro Contemporary Art Class and all my activities, Becoming Black and all these things, are for me in the ways that they’re for me, but they are also for young people. For me, I do what I can to create resources so that young people just have exposure and have access to this information and to celebrate their culture outside of like rapid pop culture, which, you know, they are their own things.

And I’m also using the Rihanna x Lorna Simpson collaboration to share that message. But it’s also interesting because all of these entities and forces are essentially often cultivated for, by, with, through the money of essentially a white gaze, which again, isn’t inherently problematic.

I find myself less excited to even use conceptual ideas that have been nurtured and fostered and created by white people. And for that reason I’m thinking about Rirkrit Tiravanija’s thoughts, who’s a Thai artist. If you look at his work, you might also kind of see it as pandering or engaging with, you know, a Eurocentric perspective. But I learned later, who knew, that a lot of his intentions and work were like—the entirety of aesthetic culture is dominated by a colonial white Euro perception and history. And he’s questioning, What is the version of this that didn’t have that? What is the Thai pinnacle of aesthetic and creative glory? That’s what he’s interested in. And think, Yes, yes. This.

I was on a class trip with my MFA program and we were at an exhibition in Canada. It was actually a white dude who was a real estate dude who owned a lot of Black art. He had an entire exhibit of Kerry James Marshall’s, which I think was like the highest collection of them, which, once you start pulling the string and unravelling this, you’re thinking, Oh, this is messed up. Why is this white land manager owning all this stuff? In the Canadian structure, there are different tiers of galleries. So there’s an upper level, but this was just a personal gallery in his office building. It was open to the public, but you had to make an appointment. And then his trained art director person would come out and give you a tour. And so this young white lady spoke. Oh, look at all these Marshall’s, and so on. So that kinda went off the rails and I just stepped away. And thought, I don’t need this.

It was interesting. Because one of the first pieces we looked at was a Kerry James Marshall sculpture that was like a little bit classic. Kerry James Marshall said, Everyone says painting is dead. And he’s like, What the fuck do you mean painting is dead? Like, it’s literally been a conversation among white makers and different people. Black people have been withheld from accessing even the discourse or the platform or the space to be participating in this conversation. So how could it be dead when it hasn’t even really been a diverse discourse? And so, yeah, that remains. It was maybe decades ago that he made that statement. And here I am at the earlier part of my career and the ideas are just beginning as a discourse in my work, in a way that Kerry’s comments can be seen as having shifted the narrative in my individual life, the same way it can be seen as having shifted the narrative in the larger art world.

It’s interesting too with the uprising after the murder of George Floyd. All the art centers started asking, Oh, what if we had a Black artist? And so that’s happening, but it’s also starting to taper off. When it was first happening, I thought, Oh man, like, I got to take advantage of these opportunities. Now, I am thinking, Oh, I’m exhausted. Like I’m just going to chill out. But, will this all be here tomorrow? Do I need to take advantage of this now, before I don’t have it to take advantage of?