Conversation Series Fall 2025 Sofa Issues

Teaching a Painting

Simeen Anjum with Tamia Alston-Ward

“The fact that you can’t read it all forces you to want to read what’s in there… There are creative ways you can educate about Black historical subjects which are being erased from our curriculums. Art is a wonderful gateway into educating people on not only contemporary, but historical, political situations and environments.”

During my summer internship in Adult Education at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, I found myself drawn to the dynamic conversations happening just next door at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where an educator institute was underway. It was there that I met Tamia, a gallery educator. I was struck by Tamia’s ability to cultivate an atmosphere of curiosity and critical engagement during gallery sessions, creating space for young learners to explore art in meaningful and thought-provoking ways. As someone exploring museum education across different institutions, I’ve been interested in how various museums approach learning in their spaces, what supports meaningful engagement and what insights I can bring into my own practice.

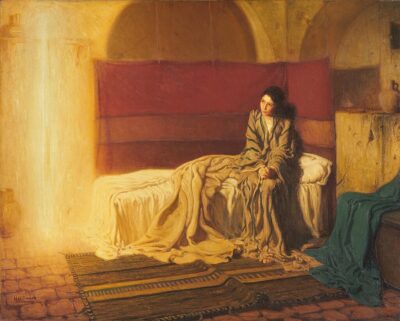

In this interview, I speak with Tamia about her role as a K–12 educator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the challenges and opportunities of working in museum education today, and what it means to teach art in a city as historically rich and complex as Philadelphia. We also delve into the work of Philadelphia-born artist Henry Ossawa Tanner, whose painting, The Annunciation, offers a historically grounded and deeply human take on a biblical scene, an entry point for considering how museums can foster more accurate, inclusive narratives.

At a time when public education is facing increasing censorship through restrictions on teaching about race, gender, and LGBTQ+ issues, museums may serve as critical spaces for dialogue and reflection. How can they support more honest, expansive conversations about history and identity? Tamia shares insight into the power and responsibility of museum educators to engage students in this important work.

Simeen Anjum: What is your favorite painting in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) that you like to talk about as a gallery educator?

Tamia Alston-Ward: I would say the Annunciation by Henry Ossawa Tanner. I have a connection to the artist through the alma mater (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts).

Simeen: Is it the one he painted in Palestine?

Tamia: Yes. I love this painting and I still teach it over and over again. And what’s cool is that it’s opposite another Annunciation painting from the Baroque era by the Spanish artist Zurbarán. It’s a great contrast and shows the differences in how the story of Mary, Jesus’ mother, is depicted across time. Tanner’s is from 1898. Zurbarán’s is from 1650.

What I love most about the painting is the expression of Mary. Tanner was really focused on historical and biblical accuracy. There are so many depictions of Mary, in the museum and around the world, but none quite like this one. He traveled to Palestine to study the architecture and the people because that’s where Mary and Jesus were from. There’s a long history of Black Christian presence here in Philadelphia that Tanner and his family were part of. His father was a bishop and the family published hymnals for churches.

Henry Ossawa Tanner: The Annunciation (1898)

But what I really love is how Tanner shows Mary in a way that I wish everyone could see. All the other versions of Mary just aren’t accurate. You can see the realism in her expression. She looks concerned. In the Bible, when Gabriel tells her that she’s been chosen, there’s a moment where she accepts it. And the expression on her face here makes it seem like she’s still in that moment, still figuring it out. She is not yet wearing the colors blue and red that symbolize her role. You don’t have to believe in Christianity to appreciate that these were real people from a real part of the world, a part of the world that’s currently experiencing real hurt, pain, and hardship through genocide. We forget that the religious figures we revere came from that area.

If I were to go online right now and search “Annunciation,” there would be so many images and almost all of them would show a much older Mary, a much whiter Mary. The architecture would be European, the curtains, the setting, the clothing, it’s all inaccurate.

The Zurbarán painting is across from it, so we do a compare and contrast activity. I’ll bring the visitors to both and use a Venn diagram. We talk about composition—Mary is on the right, Gabriel on the left, in both. But we also look at architecture, clothing—“Do you think they wore this 2,000 years ago in Palestine?” The answer is no. Definitely not. So when I show students these paintings, I ask them: After seeing this and the Zurbarán version—which one feels more accurate? And they always point to Tanner’s.

Francisco de Zurbarán: The Annunciation (1650)

All this is to say that art helps us discuss political and social issues, both from the past and today. Zurbarán’s painting is from 1650, after the medieval period when all art had to be religious. The Baroque era was dramatic and theatrical, artists were showing off their skills with drapery, perspective, etc. And the paintings were meant to depict the Bible for people who couldn’t read. But Tanner had the opportunity to travel. He made this painting in Paris, after studying at PAFA and trying to escape racism in the U.S. And you can see how that experience shaped his work, his faith, his clarity, his honesty. I think he made that painting for himself.

Simeen: I’m curious about how the Museum Educator role differs from the Docent role, and in what ways these positions overlap or collaborate. I’ve noticed that many museums are moving away from traditional docent models and shifting toward more learner-centered approaches to engaging with art, rather than strictly information-based methods.

Tamia: The docents work on a volunteer basis. And as educators, we’re constantly looking at work like, “Okay, how do we talk about different artworks to students? How do we talk about nudity?” etc. We have discussions on how to best go about teaching in the galleries. We also create the teaching resources and plan how objects of different cultural backgrounds should be taught about.

Simeen: I feel that traditional docent-led tours often don’t require deep critical engagement with the collection; they tend to focus more on familiarizing visitors with what’s on display. But museums are increasingly reconsidering how valuable it is to simply present the history of an artwork versus helping visitors actively engage with it, especially when working with visiting student groups.

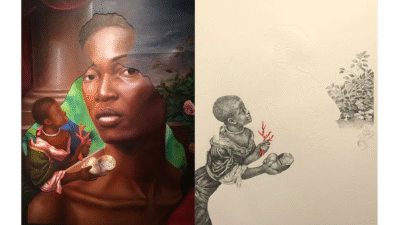

Tamia: Yeah, a lot of people who come to the museum are first time visitors, so we do a lot of highlights tours and it kind of lends itself to sameness. But the museum has been making an effort to make sure docents receive training from the educators. And they’ve done some of our K–12 tours for us, and they have great relationships with us and the students. But there was a time when an object was taught that was different from what we wanted it to be taught. It was a piece by Barbara Walker. She’s a draftsperson and she makes these drawings where one person is primarily drawn and the other is embossed.

From left to right: Seeing through Time, Titus Kaphar; Vanishing Point 24 (Mingard). Credits: Héloïse Le Fourner

So this painting right here is Titus Kaphar, and this drawing right here is Barbara Walker, and they were situated in the gallery opposite each other, so they were facing one another. They are both referencing the same artwork, a European piece by Pierre Mignard of a woman. And you can kind of barely see her in one, and then she’s cut out in the other artwork. And we see only the girl who was enslaved.

We discussed amongst educators: are we going to show the students the image that both of these artists are referencing? And we decided not to. The reason being that both of these artists intentionally cut out this European woman from these images—they’re both referencing the same image, but they are both removing, intentionally, the European image. It was in the section of the exhibition called ‘Past and Present’, it was a section dedicated to reclaiming history, basically, and contextualizing history in a different way.

So, I think one of the educators noticed that one of the docents had brought the laptop to the exhibition just to be able to show the Mignard piece to the visitors.And when we heard about that, we rolled our eyes. But again, it’s really up to the educator’s discretion if they want to do whatever they want to do on a tour. They really insisted on showing the image. And I think the main kind of discussion around these pieces was: why do we insist on showing the white figure?

Why do we need to see it, when we already can assume what she looks like based on just the outline here, this embossing and the clothes.

If you just go to the third floor of the museum, you’ll see a lot of Regency, aristocratic European figures everywhere. And the real reason why we didn’t want to show these is because this girl here is enslaved. This is a picture of a woman who is a duchess who had a painting by Pierre Mignard commissioned for her, and it was depicting her with her arm around this enslaved person. When we interpret it to the kids, we ask them close-looking questions: “What do you see?” “What do you notice?” A lot of the time, they’ll say ‘some mom and her kid’ or if it’s not a mother, then maybe it’s a sister. Because of the nature of the way the images are arranged, it makes the students think that the relationship between these two figures is tender.

But it also allows for a conversation around propagandistic imagery of the “benevolent slave owner” imagery. In the 1700s it would have looked like a really pretty, beautiful painting. But was that relationship really what it is in the painting? No, because this person was owned. And it’s another reason why we would not show the image of the woman because it’s not about her. Barbara Walker, in her drawing, makes an effort to render only the things that are relevant such as this little girl here. And Titus Kaphar in her artwork manipulates the canvas to physically cut out the woman. And then he puts a painting of another canvas inside, depicting the woman, in a way that you can’t tell who she is. So a lot of times in the galleries when we ask students “Who do you think she is?” Most of them reply with, “Maybe it’s the little girl grown up,” “Maybe it’s her mother,” “Her actual mother.”

Simeen: I am sure a lot of great discussions come from this. Has there been any other artworks lately that have allowed for more critical engagement within the museum?

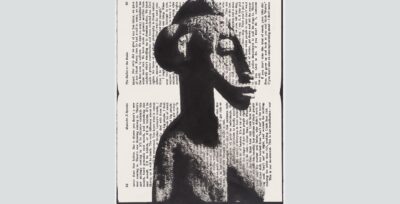

Tamia: Yes, this work from Brand X, a screen printing collective based in New York. And it is a piece depicting an African sculpture superimposed on an open book, that is oriented vertically, but you can see both the pages. It’s from a speech made by Malcolm X called ‘The Ballot or the Bullet’. My colleague, Cherish and I chose that image because we thought it would be great for teachers to understand that they can use this as a jumping-off point to talk about things that may be frowned upon by their administration. and then imposed over it, you have this African sculpture taken from 1970s “primitive” African works. And there’s no context, there’s really not much there that the artist, in the description, is telling you about the works. But there’s a lot that you can interpret from there. You can think about censorship, because you can’t see all of Malcolm X’s words. The fact that you can’t read it all forces you to want to read what’s in there. I think for students, it’s a great gateway for them to learn about many things. Learn about African objects, and why they are without context in certain spaces, anthropological context, but not in a formal or spiritual context. It makes you think about why there would be an African object mixed in with Malcolm X’s words, what is that connection? You could ask that to the students and have them research about Malcolm X as a historical figure, and this piece as an artwork. What I really enjoy about that piece, is that there are creative ways you can educate about Black historical subjects which are being erased from our curriculums. Art is a wonderful gateway into educating people on not only contemporary, but historical, political situations and environments.

Adam Pendleton: Untitled (Figure and Malcolm), 2020

Simeen Anjum (she/her) is an artist and educator based in Portland. In her practice, she explores new ways of fostering solidarity and community in response to the late-capitalist world that often isolates us. Her projects take many forms, including sunset-watching gatherings, resting spaces in malls, and singing circles in unexpected locations. She is also interested in learning and engagement within museums and art spaces. She has explored this through internships at several institutions, including the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, the Partition Museum in New Delhi, and the Littman and White Galleries at Portland State University. She currently works as a K–12 Learning Guide at the Portland Art Museum

Tamia Alston-Ward is an artist and educator based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her artistic practice is deeply rooted in research and the study of material culture in the Black Diaspora. She has worked as an educator in the National Liberty Museum, Malcolm Jenkins Foundation and currently serves as the Art Speaks Coordinator and Museum educator in Philadelphia Museum of Art.