Interviews – Spring 2022

Cover

The spring 2022 cover of SOFA Journal celebrates the subject of Benita Alioth from Shelbie Loomis’ interview, and ongoing socially engaged art project by the same name, The Art We Value. During weekly Bingo/Luncheons for the Jantzen Beach RV Park and Hayden Island Mobile Home community, where Shelbie and Benita are both residents, they became friends and ultimately collaborators in a local art show and sharing event that Shelbie organized for the project. In reading their interview, I started to think about compassion: the feeling of fellowship birthed from the suffering of others. How social forms of art can really artifact, and even celebrate, this exchange of tenderness between people. What are the forms of documentation for any given project that make this warmth and gentleness sing?

How does the documentation resonate with the people experiencing the artwork firsthand, those on their computer at home, in a book a decade later? They’re all sharing an experience of this same artwork. They may all tell a similar story of the work, when it was made and where, the materials it’s made from, and the motivation. But that compassionate feeling may be an ephemeral thing. So we ask, how do we communicate that feeling over time, which is often so crucial to the birth of the artwork when it’s in a social form?

It isn’t about requiring one way of interpreting or defining the meaning of a work. It’s more about offering a lens through which we can understand the relationship behind the work, which may offer us a hopeful possibility for the future when we feel more disconnected. With heavy hearts holding recent shootings in Buffalo and Uvalde, rising food shortages, the overturning of Roe v Wade, on top of being over two years into a global pandemic, it’s a starting point. A test for possibilities for change. Shelbie’s tender illustration of her collaborator Benita serves as documentation of the tender hope that is possible to uncover in the relational experience at the core of socially engaged artworks. Helping us to see who is aching, and who is resonating with that ache. Who is navigating the world a certain way because of it, and what strategies they are using. Ultimately, this can help us to see the limitations of our singular perspectives in favor of coming together.

Gilian Rappaport

Spring 2022

Cover Art Direction: Gilian Rappaport

Cover Art Production: Laura Glazer

Letter from the Editors

So much art is a treasure trove of references and allusions. It can sometimes feel like a scavenger hunt to look at works of art and it is so exciting when you get it! It’s like having an inside joke with the artist, even if you have never met them. Reading the interviews in this issue for example, you may notice a few people make the deliberate choice to forego capitalization in their names or the titles of their work. Rest assured this didn’t just get missed by us, the editors. This is reminiscent of bell hooks’ decision to spell her name in all lowercase, because “when the feminist movement was at its zenith in the late ‘60s and early ’70s, there was a lot of moving away from the idea of the person. It was: Let’s talk about the ideas behind the work, and the people matter less.” Was Sister Corita Kent making the decision to use lowercase letters in her titles for similar political reasons? Maybe Roz Crews’ performance piece titled with lowercase, tell us how you became so close to art, was an homage to Kent.

This idea that hooks referenced is an important notion in Social Practice, and a highlight in some of the interviews in this issue too. When talking about Sister Corita Kent’s work, Nellie Scott tells Gillian Rappaport, “The objects are not unimportant, but the message, the meaning, and the collective coming together is priority one. And the byproduct of this incredible collaboration is almost like eye candy.” This deemphasis on the object is echoed by Kenny Walls who tells his twin sister Kiara Walls, “I think that’s the power of art, whether it’s music, writing, it forces you to create the idea as well. You become the creator of that idea.”

Because our particular area of artmaking is niche, many people working this way pull from the same set of references. We often have a shared set of values. Art, and especially socially engaged art, is such a small world, but it also opens you up to how big the world is. It is a tiny tool through which to look at something huge. When we find others who see the world the same way, it is a treasure. As artist Wendy Ewald told us in a recent workshop, “I don’t usually get to meet people who think so similarly.”

The interview can be a way of finding out how people think and hopefully finding some who think the way you do. From shared family memories tied to place, as in Luz Blumenfeld’s talk with their grandmother, Aqui, to forming friendships through plants and co-mentoring youth, like in Lillyanne Pham’s conversation with ridhi d’cruz and Jackie Santa Lucia, there is a joy to be found in reading a shared language between others, as well as having that shared language, shared with you.

An interview can also be a method of learning an unfamiliar language. Like Justin Maxon, who asks others to reflect on experiences he wouldn’t be able to understand by himself. Or Laura Glazer, whose admiration and curiosity about an art piece led her to publish a book about what she learned from the artist, Ms. Melodie Adams. She now asks others, “What do you want everyone to know?” We hope the Spring Issue of the SoFA Journal connects your curiosity and questions with a couple methods for exploration.

We hope you’ll enjoy.

Caryn Aasness

Spring 2022

On Vulnerability

“What I respond to in socially engaged art is a sense of vulnerability. When I see an artist being vulnerable and then I see people responding in vulnerable ways, that’s what I’m interested in.”

ROZ CREWS

I first connected with Roz Crews the summer before I moved to Portland, Oregon. I had just been accepted to the Art and Social Practice Program and Harrell Fletcher told me that Roz, a program alum and instructor, had attended the same strange and tiny liberal arts college I had just graduated from (New College of Florida). I got in touch with her in an attempt to gather as much knowledge about this program as I could, and our first conversation clued me in to what I quickly learned could be expected from conversations with Roz: warmth, honesty, and genuine connection. Since that point, I’ve gotten to know and appreciate Roz’s teaching style by both being in a class facilitated by her and by hearing more about her experiences teaching elementary school. While I think about the kind of teacher and facilitator I want to grow into, I think it’s important to learn directly from those whose styles I admire, hence the following conversation with Roz.

Olivia DelGandio: How would you feel about talking about vulnerability today?

Roz Crews: I like that idea.

Olivia: I’ve been thinking a lot about vulnerability as it relates to teaching. I’d like to be a teacher who teaches with and through vulnerability, but with the teacher/student relationship there can easily be a lack of empathy that makes learning, and just being a person in that space, really difficult. I think you do a really great job of teaching through vulnerability and I’m interested to know your thoughts on this.

Roz: I’ve always wanted to be a teacher and I don’t think I’m naturally super empathetic, but I am naturally very sensitive and I’ve always wanted to be an empathetic teacher. I wanted to support students in all the ways that I could, and whether they are kids or adults, I really try to advocate for each person whenever I can. Sometimes that does wind up feeling like a maternal kind of role and personally, I never thought that critically about it until more recently when I started to recognize how much emotional labor goes into supporting students and the various needs that come up. You know, some years I’d have 300 students and if it’s elementary school then I’d have around 700 that I saw every week. So you can imagine that all of those people relying on and needing support from you can be challenging, especially when you’re an adjunct instructor or somebody who’s not necessarily feeling compensated for work beyond their “contract hours.” But in the same breath, I am so happy that I have been able to support people in times of need, and also just in their everyday regular life. Teachers have done that for me, and I feel kind of like I owe people that kind of support.

Olivia: It’s interesting to think about the teachers I’ve had who have played that maternal role and those who have been pretty against it. Maybe there’s some kind of middle ground where you can have boundaries while still having a deep connection to your students. What would that look like?

Roz: I think it looks like developing a strong sense of self but not letting it affect you on a personal level or else you’ll be over involved in everything. So for me it’s been about establishing a strong sense of what I believe and then committing to that, but also being flexible wherever I can. My philosophy on education is that you are really going to get out of it what you put into it. That can be a controversial point of view; especially if students or participants are expecting a more traditional “banking model” of education: where students are perceived as empty vessels ready to be filled up with knowledge, an approach criticized by folks like Paulo Friere and bell hooks. I see teaching as an exchange. And that’s my boundary actually. I’m not really there to hold your hand through a situation as much as I am to present something to you and see what you think, and then, if it’s hard, we can talk about it. If it’s good and rewarding, we talk about it. For me it comes down to self-preservation and self-awareness, and I try to teach those things to students.

Photo of a passage Olivia highlighted in their copy of bell hook’s Teaching to Transgress, 2022, Portland, OR, photo by Olivia DelGandio.

Olivia: Totally. I’m thinking about the class I took last term, the pedagogy class taught by Alison Heryer. We had to write a teaching philosophy and I was thinking a lot about vulnerability and teaching and also reading a lot of bell hooks. Something she talks about is teaching through vulnerability, but having to be vulnerable yourself before you can expect vulnerability back from your students. I feel like that’s connected to this idea of boundaries and how vulnerable you can allow yourself to be with your students.

Roz: Yes, and I certainly have been influenced by bell hooks and I think that’s where my relationship to vulnerability and teaching comes from. Vulnerability in the classroom is complicated. Certain things, I’m happy to be super transparent and vulnerable about. This was especially true when I was younger, I was like an open book. And I use that in my art practice too. I use the strategy of: I’m going to tell you whatever you want to know about me so that you will want to participate in this project and so we can have a shared sense of vulnerability. I do that in my artwork, but I also do it in the classroom and it’s changed over time in both contexts, but more specifically in my teaching because there’ve been some situations that have happened that I’ve been alarmed by. These things have shifted my willingness to be vulnerable with students and the public. It’s become harder to want to share, even though these situations are far and few between, considering all the students I’ve worked with and all of the public places I’ve put myself into.

Olivia: But situations like that can make a big impact.

Roz: They can, yeah.

Olivia: Considering all those things and how difficult it is to ask people to be vulnerable, how do you make the classroom a safe place?

Roz: I’ve really developed a strategy for quickly acclimating students to the situation that we’re going to be in for the next 10 or 15 or 36 weeks. Part of how I think of making a safe-feeling space is by trying to be vulnerable to some degree myself, more so with grad students than undergrads, and then I share even less about myself with kids. I also always create community agreements in the beginning of a class so there’s a sense of accountability. If something does happen, we can refer back to this document which includes things like “move up, move back,” which is about creating space for people who might not necessarily love being the first to talk. A lot comes up when we make the community agreements, which I find super useful as a starting place. Of course, uncomfortable things happen throughout the class, and you can come back to community agreements.

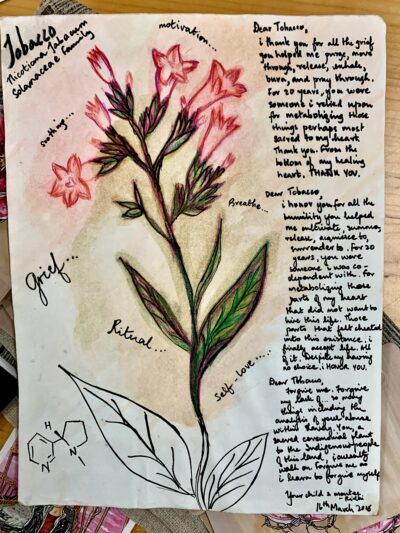

Olivia: You started talking a bit about vulnerability in your art practice. I feel like there are some similarities in how you think about vulnerability in terms of art versus teaching, but also ways that these spaces are pretty different. How do you think it shifts when you’re trying to be vulnerable in the classroom space versus in your own practice?

Roz: For me, the classroom and my practice are pretty intertwined. Even though I don’t think of my teaching as my practice, there’s a lot of times when, in my career, they have intersected. I’ve done a lot of projects at schools and I’ve also taught in schools and so sometimes I’m doing a project in the school where I’m teaching. Recently I did a performance. I was really struggling with the whole fifth grade at my new school and I was pretty desperate, so I was like, I’m going to go off the books here and just sort of see what I can do to build trust with this group. With one class in particular I said, “Hey I’m going to be doing this performance artwork and I would like it if you guys would help me create a score for the piece.” I explained what a score is and the whole time we were talking they were so engaged because I’m talking to them about something that’s really in my life and that they don’t know about. They were excited about it and I told them they could choose everything that I do during the performance; they were totally in control of this performance and I wasn’t going to change anything that they decided on. And I did everything they said, I followed through on my promise. I’m very committed to doing what I say I’ll do. So that’s one example of how my teaching intersects with my practice and involves vulnerability and trust building. Other times I’m more vulnerable in my practice than in teaching because I have less to lose when it’s not something I’m doing in an institution.

Olivia: I love that project. Do you have any other thoughts on this?

Roz: I think talking about vulnerability in the context of social practice is really important. What I respond to in socially engaged art is a sense of vulnerability. With a lot of projects, I see people putting up personal, emotional, and mental walls and that can make it hard for me to respond to the work. When I see an artist being vulnerable and then I see people responding in vulnerable ways, that’s what I’m interested in.

Roz Crews (she/her) is an artist, educator, and writer whose practice explores the many ways that people around her exist in relationship to one another. Recent projects have examined the dominant strategies and methods of research enforced by academic institutions, schemes and scams of capitalism, and the ways authorship and labor are discussed in the context of a specific art gallery. Her work manifests as publications, performances, conversations, essays, and exhibitions, and she shares it in traditional art spaces… but also in hotels, bars, college dorms, Zoom rooms, and river banks. As part of her exploration of the oppressive qualities of schools, she worked for two years as a full-time art teacher at a public elementary school in North Florida during the pandemic. She is currently a manager of community engagement programs for a collecting museum in New England.

Olivia DelGandio (they/she) is a storyteller who asks intimate questions and normalizes answers in the form of ongoing conversations. They explore grief, memory, and human connection and look for ways of memorializing moments and relationships. Through the work they make, they hope to make the world a more tender place and aim to do so by creating books, videos, and textiles that capture personal narratives in an intimate manner. Essential to Olivia’s practice is research. Their current research interests include untold queer histories, family lineage, and the intersection between fashion and identity.

Gardens in Canoes

“It was very important to always be there, to have someone doing things and staying in that place, spending time with the people. Many projects in rural communities happen in a more transitory way, and the people leave as soon as they’re over. Our idea was to really be there.”

YOLANDA CHOIS

Text by Diana Marcela Cuartas, translated by Camilo Roldán

Spanish version below

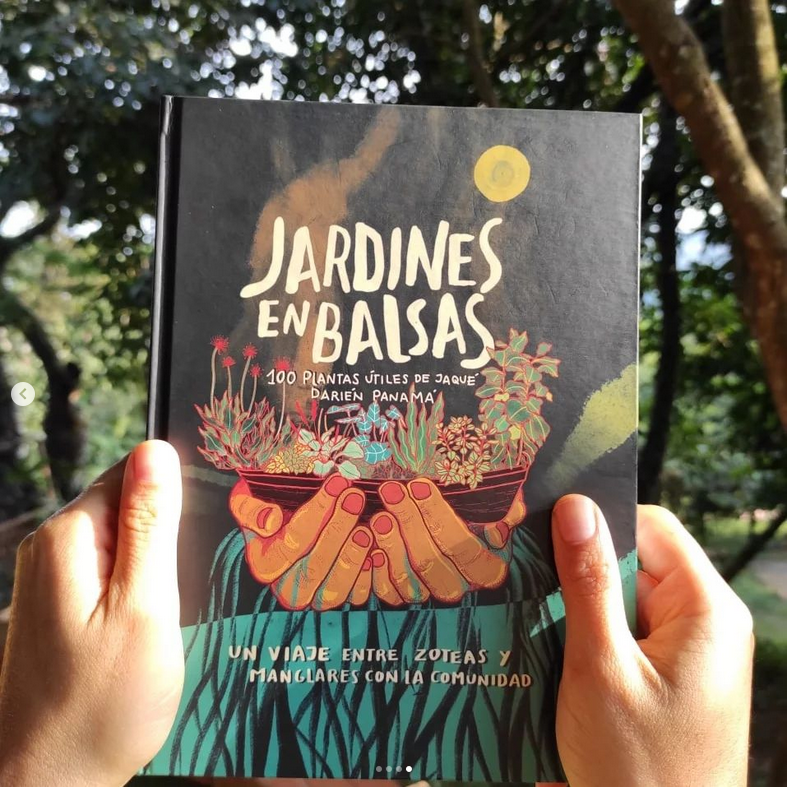

Jardines en Balsas (Gardens in Canoes) is an environmental education and community arts project, created by Yolanda Chois and Michelle Szejner in collaboration with a group of farming families. The project takes place in the township of Jaqué on the border between Panama and Colombia, on the Pacific Coast in what is known as the Darien Region. The name of this project refers to an agricultural practice called zoteas: a concept particular to the coastal communities of various places in the Chocó biogeography, which involves converting unused boats into beds for elevated gardens that can adapt to tidal changes and rising water levels in rivers.

In this interview, Yolanda and Michelle discuss a seven-year process of artistic and interdisciplinary work that, at the community’s behest, brought back this planting technique that was on the brink of being forgotten. One of the results is a book that compiles and classifies 100 usable plants in Jaqué that were collectively researched through plantings, seed exchanges, and knowledge sharing, for traditional agriculture practices and native plant identification, with a focus on local food sovereignty.

Tomatillo cultivated in a zoteas garden, Jaqué 2016 – Photo: Jardines en Balsas archive

_____________________________

Diana Marcela Cuartas: Let’s start at the beginning: How did Gardens in Canoes get started?

Michelle Szejner: I met Yolanda through a mutual friend and when we were talking she told me about Hacia El Litoral (Toward the Shore), a project that involved a trip through the Chocó region with an art collective. They were going to travel by sea, getting to know local cultures and recognizing them, compiling oral traditions, histories, and soundscapes. It was a lovely project and one of the stops was in Panama. She also mentioned that she wanted to do a recipe book and I thought my services could be helpful in identifying useful plants with the community. I told her I would request vacation days so I could meet with the collective as a volunteer. She said, “Great! Arrive on this day on this airplane,” and that’s how I arrived in a community I didn’t know, in a super remote part of Panama that very few Panamanians even know about.

Once I was there, I started to meet the farming families of Jaqué. One day, in the garden of one of the project participants, we found that there were more than 120 species of useful plants in her zoteas garden. That was when I realized that I had to return to that community. I’m a biologist and ethnobotanist and I love talking to people. I started documenting the plants I was finding, who was growing them, and what they were used for. This database started to grow, which fortunately allowed us to get more funding to continue traveling to Jaqué with Yolanda and to make the magic that happened there.

First, we wanted to connect two coastal communities, which were the Las Perlas archipelago and Jaqué, around gardens, recipes and useful plants. Later, we focused only on Jaqué, and there we went through a whole journey of workshops, volunteers, art, permaculture, and culinary arts. We were trying to recuperate traditional cooking and not depend so much on things that come from the city on ships. Jaqué is so isolated and has so many market restrictions that a ship arrives on a sixteen-hour trip from Panama City carrying stuff like cement, beer, eggs, chicken and canned goods—a lot of canned goods that have led to really high amounts of diabetes and malnutrition. And so, there were conversations about going back to eating more salads and vegetables and about using local seeds. We did a lot of work in that area. We started organizing seed exchanges, and that’s where the Gardens in Canoes came from.

Yolanda Chois: Now here’s my version of the story. Like Michelle said, with Hacia el Litoral, I had done a tour through the Chocó and Darién regions of Panama and Colombia, which have been very stigmatized by the intense violence that they experienced as a border zone. In that project, what I did was to invite people that were interesting to me to do interdisciplinary work in that border zone. Michelle was there contributing as a botanist, but we had other friendships with sociologists, documentarians, scientists and people who didn’t necessarily come from an arts background. It was conceived as a kind of residency, and then other things started to happen.

I had in mind the model of Siembra (Planting), a project that the Más Arte Más Acción (More Art More Action) foundation had done, which was also an artistic practice connecting people from other disciplines, and they had developed a recipe book. It was a search for local knowledge and plants, and this is why Michelle and I started talking about a recipe book. But later there were the particular needs of that region, of the people who we got involved with in Jaqué, the need to bring back knowledge about the zoteas, which is a practice in many communities on the Pacific Coast, and surely in many other places where there are rivers and oceans. We started talking and came up with the idea of Hacia el Litoral as a platform for people to meet and develop a lot of different kinds of projects. Some of these came to fruition; others didn’t, others came together as artworks, others became radio programs, and Gardens in Canoes was one of those projects. It was really interesting because, among all of the people who contributed to the project, there was a spirit of collectivity, ideas and feelings that motivated people to find resources. On the other hand, it was also a constant learning process for all of us who came from different ways of working.

Michelle: It was totally a two-way learning experience!

Seeds and plants exchange in Jaqué, 2017 – Photo: Jardines en Balsas archive

Diana: How were you able to integrate those working methods between arts and science backgrounds?

Yolanda: It was often very difficult for me. For those of us who work in culture, communications or art, it’s sometimes hard to place our contributions to a project, which for example: in the case of science, biology and botany, is much clearer. While my question was “How can we deconstruct our ideas about how we relate to this community?” For Michelle, the question was much more practical. She would say to me, “We have to bring tools and that’s it,” which made a lot of sense.

Art came into the project as a way to think about the relationship with the community and as a way to design strategies for bringing back that knowledge about the zoteas. For example, one of the volunteer artists devoted herself to studying biochemicals and solutions for plant diseases, and in the end, she made a handbook. At a different point, we invited an illustrator to draw gardens and spend time with the people. She was doing different cultural activities that had to do with the gardens, beyond collecting information. There were also a lot of labs where people from different disciplines were invited to work with the community to complement each person’s knowhow, instead of telling them how they needed to do things.

In the case of botany specifically, it was vital not only for scientific information, but it also helped us to establish some processes for seed exchanges that were and are essential for the project. It helped us to identify problems, and it helped us in the search for [food] sovereignty, because there is a financial control over something that shouldn’t be subject to that. It allowed us to hold onto seeds so that they would continue to exist, which is an example of how things started to intersect, and the knowledge set down in the books is definitely as much about local science as it is a huge contribution from Michelle as a scientist interested in the relationship between human beings and the vegetation.

Michelle: It also had a lot to do with the volunteers’ work. They were invited to stay as long as they wanted and the only thing we asked in return was that they would go along with the community on issues of agriculture to find and rescue seeds, through questions like: “Which seeds did your grandparents use? Which ones are they? How do you preserve them?” That was what guided us all and was what we worked on all the time, which generated other kinds of projects with other issues, but always with the community. That way we could gradually refine the botanical information and technical things about the book, so that the local knowledge would be respected and it wouldn’t contain erroneous information.

Diana: How did the community take to these interdisciplinary processes of knowledge sharing?

Michelle: It’s important to know that there was already a community structure in place and that we didn’t arrive out of thin air. There was the Escuelita de la Paz (School for Peace), where people worked a lot on the issue of healthy, non-violent education for children. There was the Colegio de la Tierra (Earth/Soil School): a high school that focused on agriculture. There is a turtle conservation project in place since 1998. All of that already existed. There were also precedents that basically set things up for us to be well received. We’ve also been lucky that the people who spent time with us and the people from the community have accepted each other. All of it has been happening from a place of good will and respect. I’ve never heard of someone who had to leave the community because they couldn’t stand it. Which is something that can happen and has happened in other projects.

Yolanda: I would also say that when we talk about community it’s not that we’re talking about all of Jaqué. Jaqué is the municipality’s main town and a meeting point for various communities that are much further up the rivers. When we say community, we’re referring to the group we work with, people who have already been acting as leaders in other projects and are accustomed to this. In fact, I think what we did was to refresh that relationship a little bit, because many other projects that happen there are international aid projects, which can often be much more instrumentalist relationships. Though they may have already become accustomed to people arriving from the outside to do things, we tried to manage a project with a more horizontal logic, although there are things that simply can’t be horizontal because of certain ways of relating that are very difficult to break.

On the other hand, the people who arrived as volunteers each had their own way of relating to people and opening up the project to other concerns. To me, that was very important because, at the end of the day, one of the valuable things about the project and the relationship between volunteers and the community was the development of other stories about such a stigmatized place. The book is, more than anything, a tool for the community to get to know the symbolic and biological wealth of their land, and as such: a tool for defending it too.

Volunteers and community members in Jaqué, 2016 – Photo: Hacia el Litoral archive

Diana: You said that you tried to establish more horizontal work dynamics. How do you approach horizontality?

Yolanda: I see it in different ways. The first thing is that it’s important to open up the relationship to resources, to funding. People should know what is the money available and how it’s being managed. Michelle would come every month with a folder with all of the information about how the funding was being used.

Michelle: I believe a lot in transparency in the data and the respect that I as a “foreigner” should show the community for allowing me to do a project there. It is an ethic that doesn’t get practiced much, but it’s vital. Transparency from financial resources to how far the project will go, what will come out of it, as well as identifying what we can’t control, the risks has been key over all these years and is at least a way to define the playing field. The budget is public, as are the activities, and also the changes that can be made. Everything is open because the project belongs to everyone. I think that changed how people were thinking about things a lot.

Yolanda: What’s more, we created a lot of strategies for being there, for spending time with people. The work with volunteers was super important because, although we did spend a lot of time in Jaqué, we couldn’t go and live there at the time. But the people who went to volunteer were there and were the project’s presence. It was very important to always be there, to have someone doing things and staying in that place, spending time with the people. Many projects in rural communities happen in a more transitory way, and the people leave as soon as they’re over. Our idea was to really be there, and we did it in a continuous way for over two years, with people tied to the project also staying in place, and that was also a way to create horizontality. Being present day in and day out, not only for the problems that affect the project, but also as part of the place.

On the other hand, there is also a more subjective process, and it’s that being in that place starts to transform how you see things, and it’s important to stay open to that possibility. Because for all of these rural communities—that are afro-Colombian, that are indigenous, that have different conditions, and are apparently distant to someone coming from the city with other problems, in a different condition. So, allowing yourself to ask who you are to that other reality is also part of the process, I think. But I don’t know if there is an ABC to these things.

Diana: With all of the possibilities for collective creation, how did you stick to the idea of making a book?

Yolanda: Initially, the reference was the project I told you about called Siembra. The process started to take a different shape, but the book always remained as an idea of how to culminate the project. What gradually changed was that it was no longer about a recipe book; it would be a different kind of knowledge that had to be there.

This was also part of our group conversations, asking what would be better for this place to leave that knowledge remaining in something; if it would be better to make a movie or a documentary—and in fact, several documentary videos were made as part of the process of returning the information to this place. This is when we decided that all that botanical work that Michelle had been doing with the families and local people should be the content. We invited the Isla en Vela, a local collective of graphic designers, to make the botanical illustrations, diagrams, and design the book, a job that we also carried out for several years. That has left us a powerful mark on collective creation for the community.

Diana: What have been your conclusions about this process, from its conception up until now?

Yolanda: I feel that, as artists, we’re used to processes that lead more to works, to some kind of physical thing. So, this practice is a little strange because it takes many forms. At one point it is an ethnobotany book; at another point i t’s local processes, and at another point it’s labs. It’s a more hybrid practice, and sometimes it is difficult for me to explain what it is in its different manifestations.

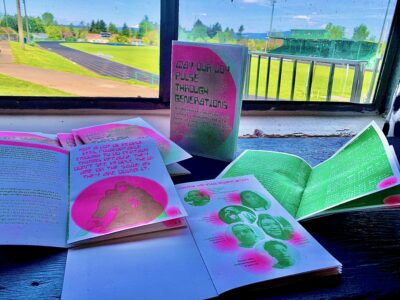

Jardines en Balsas publication, 2022 – Photo courtesy of Yolanda Chois

___________________

Yolanda Chois-Rivera (she/her) studied Visual Arts at the Universidad del Valle in Cali, Colombia. She has lived between Panama and Colombia, where she researches curatorial, artistic, and interdisciplinary practices between urban and rural territories. She has managed projects in Colombia with the Museo la Tertulia, the Goethe Institute, the Ministry of Culture, the Cultural Area of Banco de la República, and multiple artistic and environmental organizations in the global south, among others.

Michelle Szejner (she/her) is a biologist with a great passion for ethnobotany cultures, and the traditional uses of her resources. She enjoys walking with the oldest and wisest people in town; strolling through her gardens and learning about plants is what she likes the most. She is originally from Guatemala and fell in love with Jaqué in 2014, visiting continuously to plant and exchange seeds and knowledge.

Diana Marcela Cuartas (she/her) is a Colombian artist, educator, and culture worker residing in Portland, Oregon since 2019. She is currently a student at the Art and Social Practice MFA program at Portland State University. As a family engagement specialist for the Latino Network’s education department, she creates spaces for immigrant families to meet and learn within the afterschool programs offered by Portland Public Schools.

Diana Marcela Cuartas en conversación Con Yolanda Chois y Michelle Szejner

“Era algo muy importante que siempre alguien se quedara haciendo cosas y estando en el lugar, pasando tiempo con la gente. Muchos de los proyectos de que trabajan en comunidades rurales de manera más pasajera y se van tan pronto terminan. Nuestra idea era estar, estar, estar”

YOLANDA CHOIS

Jardines en Balsas es un proyecto de educación ambiental y creación artística comunitaria, creado por Yolanda Chois y Michelle Szejner junto a un grupo de familias de sembradores en el corregimiento de Jaqué, en la costa pacífica de la frontera entre Panamá y Colombia conocida como la Región del Darién. El nombre hace referencia a una práctica agrícola llamada zoteas, el cuál es un conocimiento propio de las comunidades ribereñas en varios lugares del Chocó biogeográfico,en la que se aprovechan embarcaciones en desuso para cultivar huertos elevados que se adaptan a las crecidas del mar o de los ríos.

En esta entrevista, Yolanda y Michelle nos comparten sobre un proceso de siete años de trabajo artístico e interdisciplinario buscando, por petición de la comunidad, traer de vuelta esta técnica de siembra en alerta de ser olvidada. Uno de los resultados es un libro que recopila y clasifica 100 plantas útiles de Jaqué que se investigaron de manera colectiva a través de encuentros de siembra, intercambios de semillas, y el compartir de conocimientos en torno a la agricultura tradicional y las plantas nativas, con miras hacia la soberanía alimentaria de esta provincia.

Vista de Jaqué llegando en barco – Foto: archivo Hacia el Litoral

_____________________________

Diana Marcela Cuartas: Empecemos por el principio: ¿cómo surgió Jardines en Balsas?

Michelle Szejner: Conocí a Yolanda por una amiga en común y en una conversación me contó de Hacia El Litoral, un proyecto que consistía en un recorrido por la región del Chocó con un colectivo de artistas. Ellos iban a viajar por mar, conociendo y reconociendo las culturas locales, recopilando tradiciones orales, historias y cartas sonoras. Era un proyecto precioso y una de las paradas era Panamá. Mencionó también que quería hacer un recetario y pensé que mis servicios podrían ayudar a identificar las plantas útiles con estas comunidades, le dije que pediría vacaciones si ella me permitía unirme a este colectivo de forma voluntaria. Ella me dijo “Súper! Llegas tal día día en tal avión” y así llegué a una comunidad que no conocía, en un área súper remota de Panamá, que muy pocos panameños conocen.

Estando allá empecé a conocer a las familias cultivadoras de Jaqué. Un día en el jardín de una de las participantes del proyecto, encontramos que había más de 120 especies de plantas útiles en su jardín de zoteas. Ahí me di cuenta que yo tenía que regresar a esa comunidad. Yo soy bióloga y etnobotánica y me encanta platicar con la gente. Empecé a documentar las plantas que encontraba, quién las cultivaba, y qué usos tenían. Esta base de datos fue creciendo y afortunadamente nos permitió conseguir otros recursos para seguir viajando a Jaqué con Yolanda y hacer la magia que ocurrió allá.

Primero queríamos unir a dos comunidades costeras que era el archipiélago de Las Perlas con Jaqué. Siempre con el tema de jardines, recetas y plantas útiles. Después nos enfocamos solo Jaqué y ahí tuvimos todo un camino de talleres, voluntarios, arte, prácticas de permacultura y culinarias, tratando de recuperar la cocina tradicional y no depender tanto de las cosas que vienen de la ciudad en el barco. Jaqué está tan aislado y tiene tantas restricciones de comercialización que llega un barco que se tarda dieciséis horas desde la Ciudad de Panamá llevando cosas como cemento, cervezas, huevos, pollo y enlatados, muchos enlatados que han generado unos índices de diabetes y desnutrición altísimos. Entonces surgieron conversaciones sobre regresar a comer más ensaladas y vegetales, y en torno a las semillas locales. Tuvimos mucho trabajo con este tema, empezamos a hacer intercambios de semillas y ahí surgió Jardines en Balsas.

Yolanda Chois: Ahora viene mi versión de la historia. Como mencionaba Michelle, con Hacia el Litoral yo había hecho ese recorrido entre Panamá y Colombia por las regiones del Chocó y el Darién, que han sido unos territorios muy estigmatizados por la fuerte violencia que se vive por el hecho de ser una frontera. En ese proyecto, lo que hice fue invitar gente que me pareció interesante para hacer un trabajo desde la interdisciplinariedad en este lugar de frontera. Estaba Michelle aportando desde la botánica, pero también había otras amistades sociólogas, documentalistas, científicas, y gente que no necesariamente venía del campo de la creación artística. Esto se plantea de alguna manera como una residencia y allí empiezan a pasar otras cosas.

Yo tenía el referente de Siembra, un proyecto que había hecho la fundación Más Arte Más Acción, en la región de Nuquí en el Chocó, que también era una práctica artística que vinculaba a personas de otras disciplinas y en ese caso se materializó en un recetario. Era una búsqueda por el conocimiento local y las plantas, y por eso se inició la conversación del recetario con Michelle. Pero posteriormente aparece esta necesidad propia del lugar, de las personas con las que nos involucramos en Jaqué, de que el conocimiento de las zoteas volviera, que es una práctica que viene de varias comunidades del Pacífico, y seguramente en muchos otros lugares con mar y río. Empezamos a hablar y la idea era que Hacia el Litoral sería una plataforma de encuentros para generar muchos tipos de proyectos. Algunos se materializaron, otros no, otros se configuraron como obras de arte, otros en procesos de radio, y Jardines en Balsas fue uno de esos proyectos. Era algo muy interesante porque, entre todas las personas que se sumaron al proyecto había un espíritu de colectividad, unas ideas y sentires que motivaban la gestión de recursos. Por otro lado también fue un aprendizaje constante para todos pues veníamos de diferentes maneras de trabajar.

Michelle: ¡Era un aprendizaje de doble vía totalmente!

Siembra de semillas en jardines de zoteas – Foto: archivo Jardines en Balsas

Diana: ¿Cómo lograban articular esas maneras de trabajar desde el arte y la ciencia?

Yolanda: Para mí muchas veces era difícil. A nosotros los que trabajamos en cultura, comunicación, o arte, a veces nos cuesta ubicar lo que estamos colocando en los proyectos. Cosas que por ejemplo en el caso de la ciencia, la biología y la botánica son muy claras. Mientras para mí la cuestión era “¿Cómo deconstruir la idea de la relación con la comunidad?”, para Michelle la cuestión era mucho más práctica. Me decía “Tenemos que llevar herramientas y punto”, lo cual tuvo mucho sentido.

El arte entraba en el proyecto para pensar las relaciones con la comunidad y en diseñar estrategias para que ese conocimiento de las zoteas volviera. Por ejemplo, una de las artistas voluntarias se dedicó a investigar sobre bioquímicos y soluciones para las enfermedades de las plantas y al final hizo un manual. En otro momento invitamos a una dibujante para dibujar jardines y estar con la gente. Ella estuvo haciendo diferentes actividades culturales que tenían que ver con los jardines, más allá del levantamiento de la información. También se montaron muchos laboratorios en los que se invitaba gente de diferentes disciplinas a trabajar en comunidad para complementar los conocimientos que cada quien tenía en lugar de decirle cómo tiene que hacer las cosas.

En el caso de la botánica específicamente, fue vital no solo por la información científica, sino que nos ayudó a establecer unos procesos de intercambios de semillas que fueron y siguen siendo vitales para el proyecto. Nos ayudó a señalar problemas y a buscar soberanía, porque hay un control económico sobre algo que no debería tenerlo. Nos permitía mantener las semillas para que siguieran existiendo. Esto como un ejemplo de cómo se iban cruzando las cosas, y en definitiva el conocimiento depositado en el libro es tanto de ciencia local, como un gran aporte de Michelle como científica interesada en la relación de los seres humanos con la vegetación.

Michelle: También tenía mucho que ver con el trabajo de los voluntarios. Se les invitaba por el tiempo que ellos quisieran y lo único que se pedía era que fluyeran con la comunidad en temas del agro, las semillas, para encontrar y rescatar semillas. Desde preguntas como “¿Qué semillas usaban tus abuelos? ¿Cuáles son? ¿Cómo se conservan?”. Eso nos guiaba a todos y se trabajó todo el tiempo, generando otro tipo de proyectos con otro tipo de temas, pero siempre con la comunidad. Esto nos permitió ir afinando la información botánica y cosas técnicas del libro para que respetara el conocimiento local y no incluyera información errónea.

Diana: ¿Cómo era la acogida de la comunidad con estos procesos interdisciplinares de compartir saberes?

Michelle: Es importante saber que ya había una base comunitaria y no es que llegamos ahí de la nada. Estaba la Escuelita para La Paz, donde se trabajó muchísimo un tema de educación hacia los niños, sana, no violenta. Estaba el Colegio de la Tierra, una secundaria con enfoque agro. Hay un proyecto de conservación de tortugas desde 1998. Todo eso ya existía. Había antecedentes que básicamente nos abrieron el camino para tener buena aceptación. También ha sido muy especial que las personas que nos han acompañado y las personas de la comunidad han sido bien recibidas entre ellas. Todo se ha movido desde un lugar de buena voluntad y respeto. Nunca he sabido que hay alguien que se tiene que ir de la comunidad porque no lo aguanta. Que es algo que puede pasar y ha pasado en otros proyectos.

Yolanda: También te diría que cuando hablamos de comunidad no es que hablemos de todo Jaqué. Jaqué es una cabecera municipal que es un punto central para varias comunidades que están mucho más adentro en los ríos. Cuando decimos comunidad, nos referimos al grupo con el que trabajamos, que son personas que ya venían de muchos años atrás siendo líderes de otros proyectos y estaban acostumbrados a esto. De hecho, creo que lo que nosotros hicimos fue refrescar un poco esa relación, porque muchos otros proyectos que suceden allí son proyectos de cooperación internacional, que muchas veces puede ser una relación más instrumentalista. Aunque ya estuvieran acostumbrados a que llegue gente afuera a hacer cosas, nosotros intentamos gestar un proyecto en una lógica un poco más horizontal, aunque hay cosas que es imposible que sean horizontales por cierto tipo de relaciones que ya son muy difíciles de romper.

Por otro lado, las personas que llegaban como voluntarias tenían cada uno su propia manera de relacionarse con la gente y abrir el proyecto a otras cuestiones. Para mí eso era muy importante porque al final de todo, una de las cosas valiosas del proyecto y la relación de los voluntarios con la comunidad fue generar otros relatos de ese lugar tan estigmatizado. El libro es una herramienta sobre todo para la comunidad para conocer la riqueza simbólica y biológica de su territorio, y en esa medida también poder defenderlo.

Intercambios de semillas en Jaqué – Foto: archivo Jardines en Balsas

Diana: Mencionaste que ustedes trataron de establecer unas dinámicas de trabajo más horizontales, ¿cómo se intenta la horizontalidad?

Yolanda: Yo lo veo de varias maneras. La primera es que la relación con los recursos, con el dinero, es importante abrirla. Que la gente sepa qué dinero hay, cómo se está manejando. Michelle cada mes llegaba con una carpeta donde estaba toda la información de cómo se estaban ejecutando los recursos.

Michelle: Soy bien creyente de la transparencia de los datos y el respeto que que yo como “extranjera” le debo a la comunidad por permitirme hacer un proyecto ahí. Es una ética que no se practica mucho pero es vital, la transparencia desde los recursos económicos hasta el dónde vamos a llegar con el proyecto, qué va a salir de ahí; así como identificar lo que no podemos controlar, los riesgos. Eso ha sido clave en todos estos años y es al menos es “marcar la cancha”. El presupuesto es público, tanto como las actividades, y también los cambios que se pueden hacer. Todo está abierto porque el proyecto es de todos. Creo que eso cambió mucho la forma de pensar.

Yolanda: Además, creamos muchas estrategias de estar en el lugar, de pasar tiempo con la gente. El trabajo con voluntarios fue súper importante porque, aunque nosotras sí pasábamos bastante tiempo en Jaqué, no nos podíamos ir a vivir allí en ese momento. Pero la gente que fue voluntaria estaba allí y era la presencia del proyecto, era algo muy importante que siempre alguien se quedara haciendo cosas y estando en el lugar, pasando tiempo con la gente. Muchos de los proyectos de que trabajan en comunidades rurales de manera más pasajera y se van tan pronto terminan. Nuestra idea era estar, estar, estar, estar, y lo logramos sin interrupción por más de dos años, en donde la gente que estaba vinculada al proyecto también estaba en el lugar y eso también era una manera de intentar la horizontalidad. Estando presente en el día a día, en los problemas que surgen no sólo con el proyecto, sino como parte del sitio.

Por otro lado, también hay un proceso más subjetivo y es que el estar en ese lugar te empieza a transformar la mirada sobre las cosas y es importante abrirse a esa posibilidad. Porque en el caso de todas estas comunidades que son rurales, que son afro, que son indígenas, que están en otras condiciones y evidentemente tienen una distancia para el que viene de la ciudad con otros problemas, en otra condición. Entonces el permitirse cuestionar quién sos por esta otra realidad también creo que hace parte del proceso. Pero no sé si hay un A,B,C de estas cosas.

Diana: ¿Con todas las posibilidades de la creación en colectivo, cómo se sostuvo la idea de hacer un libro?

Yolanda: Inicialmente el referente era el proyecto que te dije que se llamaba Siembra. El proceso se fue dando de otra manera pero el libro siempre se conservó como la idea de culminar el proyecto en un libro. Lo que fue cambiando es que ya no se trataba de un recetario, sino que era otro conocimiento el que tenía que estar.

Esto también fue parte de las conversaciones en grupo, preguntarnos qué es mejor para ese lugar en términos de que su conocimiento quede fijado en algo. Si sería mejor una película o un documental, y de hecho sí se hicieron varios videos documentales como parte del proceso de devolver la información al lugar. Ahí decidimos que todo ese trabajo botánico que venía recopilando Michelle con las familias y personas locales debía ser el contenido del libro, invitamos al colectivo Isla en Vela para realizar las ilustraciones botánicas, para diagramar y diseñar el libro, un trabajo que también realizamos durante varios años y que nos ha dejado una huella muy fuerte desde la creación colectiva para una comunidad.

Diana: ¿Cuáles han sido tus conclusiones con este proceso desde su concepción hasta ahora?

Yolanda: Siento que como artistas estamos acostumbrados a unos procesos que devienen más en obra, en algún tipo de cosa física. Entonces esta práctica es un poquito extraña porque tomó muchas formas. En un momento es un libro de etnobotánica, en otro momento son procesos locales, en otro momento son laboratorios. Es una práctica más híbrida y a mí me ha costado, que ahí en sus diferentes instancias se comprenda qué es lo que es.

Mural sobre los jardines en zoteas – Foto: archivo Jardines en Balsas

Yolanda Chois Rivera

Licenciada en Artes Visuales, ha vivido los últimos años entre Panamá y Colombia. Realiza prácticas curatoriales, artísticas e interdisciplinarias entre territorios urbanos y rurales. Ha gestionado proyectos en Colombia con el Museo la Tertulia, Goethe Institute, Ministerio de Cultura, Área cultural del Banco de la República entre otras instituciones y con fundaciones artísticas y ambientales en el sur global.

Michelle Szejner es bióloga con gran pasión por la cultura etnobotánica y los usos tradicionales de sus recursos. Caminar con los más grandes y sabios del pueblo, pasear por sus jardines y aprender de plantas es lo que más le gusta. Es originalmente de Guatemala y se enamoró de Jaqué en el 2014 y junto con su hijo no han dejado de visitarlo y continuar sembrando e intercambiando semillas y saberes.

Diana Marcela Cuartas es una artista, educadora y trabajadora cultural colombiana, radicada en Portland desde 2019. Actualmente es estudiante de Maestría en Arte y Práctica Social en Portland State University y trabaja en el departamento de educación de Latino Network, como especialista en participación familiar, generando espacios de encuentro y aprendizaje compartido para familias inmigrantes a través de programas extra curriculares en escuelas secundarias de Portland.

Come Together In Joy

“What would it look like if we could come together, not in protest, but in joy, and center these very real human issues, such as poverty and world hunger?”

NELLIE SCOTT

Two month has passed since the debut incarnation of my project The Gatherade Stand; a co-authored art project in the form of a lemonade stand that serves drinks made from wild-foraged plants and creates opportunities for collaborative creativity centering those same plants. I initiated the project in Spring 2022 in Portland, Oregon at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. School to encourage the connection of students and their communities to the natural world through the King School Museum of Contemporary Art (KSMoCA) a contemporary art museum and social practice art project inside the elementary school. Since its inception, The Gatherade Stand has supported community building, nature education, and cross-disciplinary artmaking through collages, drawings, poems, audio works, and soda making.

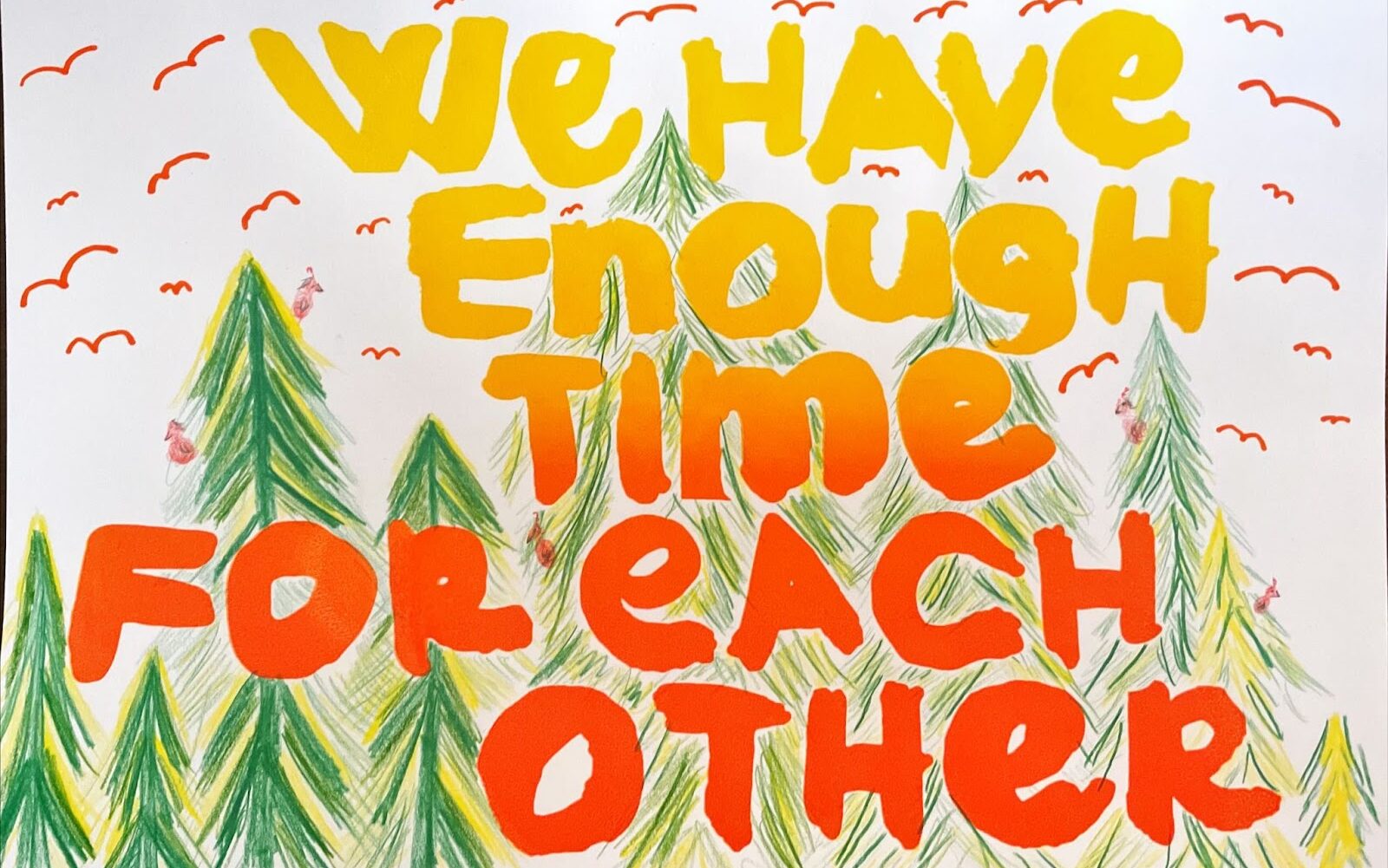

The inaugural spring season of The Gatherade Stand was dedicated to the nettle plant. Alongside serving nettle tea, we began by displaying a large wooden sign that proudly appropriates Gatorade branding, which pivots on the interests of the fifth grade audience. We then made visual artworks that responded to the prompt: “If a nettle plant made a protest sign, what would it say?” We hosted a table at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. School Celebration Day and offered a collaging prompt inspired by nettle shapes. Further workshops facilitated song and poetry writing about and for the nettle plant and making soda from dried nettle leaves inside a school classroom. Finally, DJ and composer DJ Tikka Masala was invited to collaborate on an audio piece about nettle. As I gear up for the project’s first big culminating moment through an interactive installation for The Gatherade Stand 01 at Assembly 2022 at KSMoCA, I’m asking: How much of The Gatherade Stand is about Pop Art? How much is about adequacy, “the idea of making art that barely passes the threshold of being art (Harrell Fletcher. An Incomplete and Subjective List of Terms and Topics Related to Art and Social Practice Volume One, 2022)”? What is the message behind this blend of nature, mass culture, fifth grade voices, and co-creation? How does it all relate to this urgent moment of climate catastrophe?

I gained a treat on this trail of wanderings when my astute classmate, Laura Glazer, referenced the artist Sister Corita Kent in response to The Gatherade Stand sign. She remarked on synchronicities with Corita around Pop Art and co-authoring with students. My curiosity was immediately piqued around Corita’s incorporation of advertising images and slogans as well as popular song lyrics, biblical verses, and literature as a strategy to connect with a broader audience. I also wanted to learn more about the increasingly political direction in her work, as she urged viewers to consider poverty, racism, and injustice. On top of that, I discovered how prolific she was, and collaborative in terms of working relationships with students as well as businesses and nonprofits that aligned with her mission: at the time of her death, she had created almost 800 serigraph editions, thousands of watercolors, and innumerable public and private commissions. Corita’s work inspires me as I continue to develop The Gatherade Stand, with the ultimate aim of building connections to the natural world at this crucial moment. To my delight, Nellie Scott, director of the Corita Art Center and PSU alumni, was eager to converse around my questions.

Gilian Rappaport: Would you consider Corita Kent a socially engaged artist?

Nellie Scott: When I consider what she was doing at The Immaculate Heart College in the 1960s while she was a nun, what she was doing with her students, and the proto-happenings, it does feel very rooted in the social practice ethos. She offers an interesting intersection between Social Practice and Pop Art, which is her most frequent association.

Gilian: I’m interested in exactly that intersection.

Where did the Wonderbread imagery come from, and who were the students that she was collaborating with at The Immaculate Heart College?

Nellie: Pop Art was really a tool for her at the intersection of faith, art, and social justice. In wonderbread, she’s drawing very much from Wonder Bread packaging. In 1962, there were many things happening at the same time in a fruitful way. Vatican II was this larger calling in Catholic history to think about who they’re serving and how they’re serving them, and it even changed the language that they were using to connect with people in mass, which went from Latin to English. That’s one of the reasons that Corita began appropriating packaging.

Also, The Immaculate Heart College was this incredible location for women’s education. Ultimately when many left and sought dispensation from their vows, 40% had master’s degrees or higher. And it wasn’t just the art department getting accolades, it was also the science department, and people were publishing books. It was a hotbed of creative activity. Her students were this active hub of young women primarily, often in their undergraduate study. There are great stories about her students, it was a very creative environment that was very collective in its practice. They were often the ones hanging the screens by little pins all over, and helping to clean the screens.

It’s also important that a grocery store went in across the street, right next to the space that the college was using for printmaking, which was ultimately Corita’s studio. They walked into the grocery store using a tool called a viewfinder, which is a one-inch-by-one-inch square that Corita was using to teach her students how to see again. This is part of her approach to social justice as well. Sometimes taking in the whole picture can be overwhelming, but by isolating small parts and focusing on just that little bit, one can find gratitude in that place and create change. In this way, she was teaching them to see again.

Gilian: Was it intended for her students or was she envisioning a broader national or international audience?

Nellie: She was a nun, and her art practice was always for the common good and the greatest audience possible, versus as a tool in the marketplace. It came down to how she saw her contribution to her order. She believed that everyone had a job to do as part of a collective whole, and her artwork was, in some cases, a way to provide resources for the order.

Being a nun and having taken the vow of poverty, she wasn’t using the most expensive materials. Printmaking is a really democratic medium, but was mostly used in commercial settings. When she was at USC, she printed on paper towels from the bathroom. She was using what was the best that was around her, and finding inspiration there too.

Also, she wasn’t working in a silo. She had seen the Duchamp show at the Pasadena Art Museum, which many of the West Coast, mostly male, Pop Artists had seen and drew inspiration from. She was going on long lecture tours across the country, had an exhibition in New York, and was cross-pollinating with a lot of the artists that were working at that time.

Once she started screen printing, she quickly began getting more attention and ultimately became a lightning rod of thought, hope, and conversations around the subjects in her work. And she was always taking on commissions for nonprofits and causes that she believed in. She knew her work was valued, which enabled her to give further. This wasn’t a typical model at the time.

Gilian: What, if anything, do you see as Corita’s unique contribution to social forms of art as a discipline?

Nellie: There are so many milestones to touch on there. The one that is most well known is her Ten Rules which still hangs in many classrooms and art studios. She made those in her classroom by asking “What’s important in being a student, and what’s important in being an educator?” From there, they curated these rules together.

Also, when we think about her happenings now, they feel like prototypes to what later became central to the counterculture identity of hippie festivals in California.

In 1964, Corita was tapped, as the Head of the Art Department, to rethink the Mary’s Day celebration. Years prior, it very much centered on Mary and it had always been kind of a straightforward, traditional event. Corita was put in charge with her students, and they extended this practice that she was already doing of processions. The Vatican and the Pope were concerned about world hunger. Corita, the Order of Immaculate Heart of Mary, and the students of the Immaculate Heart college completely redecorated the college campus in Hollywood, and also created incredible signs and banners that spoke to this cause.

A lot of people think Mary’s Day was a protest, but it was a procession. The idea was: what would it look like if we could come together, not in protest but in joy, and center these very real human issues, such as poverty and world hunger? And there’s food packaging everywhere because Corita and her students just went into the grocery store, and were like, “You have some extra boxes? Great, we’re going to take them.” And they built these larger box towers by painting and decorating those directly to be stacked on top of one another. The students created the vision and social justice messaging throughout these works as well.

Gilian: Will you share more about the box towers?

Nellie: The box towers continued with her students well beyond Mary’s Day. For example, there’s Peace on Earth, a commission by IBM in 1965 for an installation in the form of a Christmas window display for their showroom on Madison Avenue in New York. Corita offered her students Mickey Myers and Paula McGowan directorship on the commission, which she had received days before, and worked out the contract. The students created an exhibition using 725 cardboard boxes, and featuring quotes by five recently deceased men of peace: Pope John XXIII, JFK, Adlai Stevenson, Dag Hammarskjöld, and Jawaharlal Nehru. Newspapers across the country ran stories claiming that the students and Corita had protested the Vietnam War through the art installation on the most consumerist street in New York City, Madison Avenue.

This was a great example of her collaborating with her students for a message, and centering that message as the reason behind the art. The objects are not unimportant, but the message, the meaning, and the collective coming together is priority one. And the byproduct of this incredible collaboration is almost like eye candy, when your eyes go across all of these messages your heart stops. You realize how relevant those messages are today.

Nellie: Her pedagogy is this incredible, rich thing that she left us. These fundamental practices in education are things she was doing with her students forever ago. It’s such a well of inspiration to draw upon.

Gilian: In what ways are you drawing upon that inspiration today?

Nellie: Since you are in Portland, I wanted to mention that Kate Bingaman-Burt, Co-Director of the School of Art and Design at Portland State University, was the Artist-in-Residence at the Portland Art Museum while the Corita Kent: Spiritual Pop (2016) show was up at such a pivotal election time. Kate made a call out for the term “power up” and ultimately made a screen print of power up that was distributed more widely.

power up is a print that Corita made in her studio. The Los Angeles Archdiocese at the time had banned the radical priest Daniel Berrigan from presenting at the college, and at this time, he wasn’t even the radical person that we all know and love. So Corita took his words and made this artwork, and then made it into an installation for the students for reading and perhaps prayer. She was thinking of this hierarchy of what might be traditional prayer versus reading the current events of our time as a participatory citizen and human.

So in 2016, at the Portland Art Museum, this work was on display, and people were visiting it the day after the election and finding solace in these words that were made 50 years ago.

Nellie: Also, last year, we had a cohort of students through our video program Learning by Heart. The program takes its name from the seminal book Learning by Heart: Teachings to Free the Creative Spirit that Corita co-wrote with Jan Steward, which details the teaching methods that she developed.

At the end of our partnership program with Casa Esperanza, a youth program in Panorama City, as a kind of culmination, we asked them, “If you could have a message that you could broadcast to your neighbors, what would that look like? What would it be?” We were working with a lot of immigrants, and we created a box tower together with that message as this temporary installation in their neighborhood.

At the Kennedy Center last week [May 1, 2022], we debuted POW POW POWER UP: Someday is Now, an opera installation, which was made collaboratively by interdisciplinary artist Liss LaFleur, composer Samuel Beebe, and the Corita Art Center, and performed by choral ensemble The Artifice. This performance is the first of 29 mini-operas, each referencing one individual artwork from Corita’s heroes and sheroes series. This inaugural performance was inspired by the artwork titled green fingers, and gathered a community to center on environmental justice. We invited participants to join the performance in a celebratory procession a la Mary’s Day.

Nellie: We also hosted a hands-on art-making event in Los Angeles on Earth Day with Self Help Graphics & Art, with instruction by lead teaching artist Oscar Rodriguez. It was founded by a woman named Sister Karen, who was a former student of Corita’s. Participants had the opportunity to create and personalize posters that featured some of Corita’s iconic words and phrases. The collection of posters traveled to Washington, D.C., and became part of the performance at the Kennedy Center.

We asked the participants to center themselves, in many ways like a love letter to a stranger involving environmental justice and respond to the prompt, “What does it mean to be a human on this earth?” Some of the signs were so beautiful and timely in that conversation. Also, the individuals who carried them in D.C. had never met the people who made them in Los Angeles, yet can see their name, their message, and be torch bearers of that message in this larger procession.

It was an act of interconnectivity, in a way that will be crucial in days and years to come in really talking about environmental justice. It was a reminder, if people didn’t learn this from COVID, that we are all connected. Just because we live in one state doesn’t mean that we don’t affect another state. We are one planet.

Gilian: Do you have a favorite of Corita’s 10 Rules?

Nellie: With this project, our effort is to “consider everything an experiment!” We [Corita Art Center] very much approach what it is that we’re doing, supporting, and thinking through as experimentation. As an organization, we’re going to get a lot of things wrong, and we’re going to get a lot of things right. In that process, there’s so much understanding in feedback.

We’re very fortunate to be the stewards of her legacy. We’re participating in so many different worlds—as a nonprofit and also as an artist estate. We’re always asking, “What’s the meaning of all of this? How do we actually use her work? And also feed people? How do we use her work for mental wellness, and to talk about these very heavy topics, and this wonderful intersection of faith and art and social justice? How can you be the stewards of a legacy but also meet the ethos she presented in her lifetime?”

*

*

Nellie Scott (she/her) holds her degree in Art History from Portland State University and Szeged University in Hungary. With art accessibility as a pillar to all of her professional endeavors, Scott has spent the last decade developing exhibitions and art education initiatives geared toward democratizing art engagement. Prior to holding the position of Director at the Corita Art Center, she served as an independent consultant and art advisor for a variety of public and private foundations, institutions, artists, and estates.

Gilian Rappaport (they/she) is an artist, educator, and naturalist. In this urgent moment of climate catastrophe, their practice is asking, what can we learn from closeness with nature, and the paths to get there? They believe co-authorship can deepen our connection to ourselves, our communities, and our natural environments. The granddaughter of Ashkenazi migrants by way of Russia and Poland, they were born and raised in New York between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. Gilian is openly queer, and lives and works in Rockaway Beach, Queens and Portland, Oregon. Follow them @gilnotjill.

The Tapes, Conversation III

“Peggy Burton was a teacher at Salem High School who got fired in the late ‘60s or early 70s because she was gay. Charlie Hinkle took her case. In those days, there was hardly a gay rights movement, it just barely started. He took her case to the ninth circuit. They won the case, but he took it on free speech grounds.”

CINDY CUMFER

The Tapes, Conversation III is the third in a series of conversations about a collection of archived audiotapes that are held within the Portland State University Special Collections and Archives. What the tapes hold are the intimate stories of lesbian mothers and gay fathers who were up against court systems that denied them of custody and their parenting rights because of their sexual orientation and gender identies in the 1970s and 1980s. The tapes are closed to the public because there is no information about who is recorded, therefore gaining permission to share their stories has been a difficult path to forge. Together, we; Marti Clemmons and Rebecca Copper, are working to track down who is on these tapes in hopes to gain permission to release these valuable stories to the public. In our search for those identities, we’ve recorded conversations with those we have been able to get in touch with. Through these conversations, we’ve simultaneously garnered first-hand accounts of the LGBTQ history in Portland, Oregon as it connects to parenting rights.

In the first conversation, we spoke with Gilah Tenenbaum, whose name Marti found written on one of the audiotapes. Gilah spoke to us about their connection to the tapes and led us to Katharine English, who we spoke to in the second conversation. In the second conversation, we invited both Gilah and Katharine to discuss the tapes with us. The two of them talked about the history of the Portland queer community and the cases they remembered together. In this conversation, we learned that Cindy Cumfer and Pat Young could be tied to these audiotapes. In the following conversation, Cindy Cumfer and Pat Young with Katharine, Gilah, Marti, and myself met to discuss the possibility of who could have been a part of making these tapes. We also discuss their past work as laywers in the queer community and one as a writer for Just Out.

Cindy and Pat both helped add historical context to the conversation. Though Cindy and Pat were not parents themselves, they understood the importance of the right to parent. Cindy was the first lawyer to get a signed adoption for a gay couple in the United States. Together, Cindy and Pat co-organized feminist resource spaces in Portland to support queer parents in the community.

Rebecca Copper: This meeting is about a group of audiotapes Marti shared with me that were donated or given to the PSU archive. The audio tapes are closed to the public. Marti works in the archive and could probably speak better to the audio tapes than I can.

Pat Young: The tapes are from the women’s bookstore, right?

Marti Clemmons: Yeah, from In Other Words. The collection was donated when they closed down a few years ago– four or five years now. One of the boxes contains multiple cassette tapes, some of which are labeled with a name of the person interviewed, but not the interviewer. It makes it a little harder to identify the voices. There’s about 50 tapes in here. They all date from, like, ‘78 to ‘81, ‘82.

Katharine English: What are you trying to do with these tapes, Marti and Becca?

Marti: For the archives at Portland State, it’d be great to have whoever we can identify sign off forms so we can eventually digitize them. Of course, there are things that come along with that. Not everyone can be identified by voice. Pat, I think that you are on one of the tapes. I took a class with Pat in 2012, a capstone LGBT class. I recognized Pat. Really, I swear, it’s your voice. Katharine, you mentioned that Pat was the one that interviewed you, right?

Katharine: Yes.

Pat: That was for Just Out, the newspaper.

Katharine: I remember it being for archives, for Portland State. It might have been for Just Out; I did a lot of interviews.

Pat: That’s when I wrote that article about those two women or something, or a wedding? I don’t know anymore. Obviously, we’re all old. [laughter]

Katharine: Well, I think you were questioning me about all the work that I did in gay custody. I think it was broader at that time, but you asked me about the leatherbound women case. [laughter] I call it my “leatherbound women” case. I think it was for more than that, but that was a story that stood out.

Pat: Yeah. I’m not remembering. So, there you have it.

Marti: All these tapes are custody-based. Pat, do you know—sorry, this is the archivist in me talking, but, the Just Out interviews, are those at OHS (Oregon Historical Society) with Robin?

Pat: I have no idea, you’d have to check with Robin or Oregon Historical Society. I don’t know what happened to all of the Just Out items. I mean, other than their paper versions, I don’t know what happened to any of them. If they had any audio files, certainly they had a lot of photos.

Marti: Great, thank you.

Rebecca: To give a little bit more information about why we’re all here together; as Marti mentioned, we are trying to find who is on these tapes. When we first found Gilah Tenenbaum, who’s not here right now, I had an interest in documenting these conversations as we were trying to find who is on the tapes. It was published in the SoFA (Social Forms of Art) Journal. I’m a graduate student at Portland State University. This journal is put out by my program. A lot of this history has come up in these conversations. While searching for who is on these tapes, we are simultaneously trying to document these conversations. Marti and I are collaborating on an archive that is based on the single parent experience and Marti shared these tapes with me one day when I was visiting them at the Portland State Archives.

Cindy Cumfer: Gilah’s connection with all this… I didn’t know she didn’t work in this area, so I’m just curious.

Rebecca: Gilah was on one of the tapes, one of the first names that was identified. So, then I got on the internet and we got a hold of Gilah.

Cindy: Katharine, do you know if she did work about custody?

Katharine: I don’t think she did. She was in the community, but I don’t think she did work on custody cases. What did you do, Cindy, in custody cases?

Cindy: I litigated a few of them. Maybe late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Then, I did the first two same-sex parent adoption, which is a different topic, in ‘85.

Katharine: Was Judge Deiz the judge on those adoptions?

Cindy: I did a number of adoptions, but she was the judge on the first adoption, yeah.

Katharine: On the first single sex adoption?

Cindy: Yeah, in ‘85. Then, some of the other judges fell in line.

Katharine: Would those clients mind if you reveal their identities?

Cindy: I don’t know. I’d have to ask them. I do still know them. You helped out on that.

Katharine: Oh, yeah. I know who they were.

Cindy: I dragged you into that. [laughter]

Katharine: Haha, you didn’t drag me into it.

Cindy: I think you were late. She (Judge Deiz) had already signed the order. But then she looked at you and started laughing when you came in. She said, “You came to check-in on me, huh?”[laughter]

Marti: When was the last time that you spoke with Cindy, Katharine?

Katharine: Oh, gosh, when did we last speak, Cindy? Years ago.

Cindy: I came to town for your book reading.

Katharine: Oh, yes. That’s right. That was about five years ago, wasn’t it? But, you’re always in my thoughts, dear.

Cindy: [laughter] You too. Are you in Utah right now?

Katharine: Ah, yes, I’m in Utah, by the mountains and the conservative community. [laughter]

Pat: I’m sure you’re good for the community there. [laughter]

Katharine: I’m not sure if that’s how it will go, it’s fine [laughter]. I figure I’ve passed the torch, I can kind of be in the background again.

Cindy: Does anybody know how Gilah is involved? I’m just wondering because we’re waiting for her. Her name just popped up? Did she do custody work? I thought she was a (workers’) comp hearing person.

Katharine: She did some wills in the States. I’m not sure. She didn’t do any custody work. She always sent her custody cases to me, or perhaps to you. I got a lot of referrals from her.

Marti: Yeah, she’s mentioned on the Excel spreadsheet as someone who was in the community, but not necessarily involved in the custody cases, but more as a support. I know on tape, she does speak specifically about the judicial system and just helps give a kind of a background.

Cindy: I see. I was one of the people who helped start the Women’s Place bookstore. I didn’t realize they had all these tapes, good for them. That was in 1973 I think or something. That was before law school.

Katharine: Oh, that’s right, when it was on Grand Street? I remember that. [laughter]

Cindy: Back when it was a women’s center. You came to our opening.

Katharine: [laughter] I came, I was in my little frotte dress.

Cindy: Nobody had thought a man would come. Madeline Warren and I sat and chatted about it. [laughter]

Katharine: I know! I came with my husband! It was too funny. I had on red, white, and blue stars on my little jumper. I had on nylons and heels. I was all dressed up because I came to this planning meeting. I walked in and I was sort of surprised when my husband walked in with me. Some woman, who looked at the time to me, like this great, huge, hulking lumberjack, came out and said, “Hi, what are you here for?” I said, “I’m here for the planning meeting.” She said, “Well, it’s through those beads.” We both started to walk through and she stepped in front of my husband and said, “Men aren’t allowed.” [laughter] I thought, “Oh, my God, what am I gonna do?!”

Cindy: That was a different occasion. I don’t know about the planning meeting. This was the grand opening of the bookstore, which was in the front half. You guys just came in. Madeline and I looked at each other. It hadn’t dawned on us that a man would even want to come. We knew we had to be open to men when we were open to the public.

Katharine: Oh well, it must have been a different time. But, It was all downhill from there. [laughter]

Cindy: That was a great project.

Katharine: Yeah. So, what kinds of things did you need to know, Becca?

Rebecca: These conversations have unfolded in an organic kind of way. First, I reached out to Gilah. Then, Marti and I had a conversation with Gilah who mentioned Katharine’s name. So, I tracked down Katharine and we had a conversation with Gilah and Katharine. Pat, your name came up several times, and, Cindy, your name came up as well. I thought it would be good to connect everybody and talk about what was happening when these tapes were recorded and hopefully figure out more about who is on these tapes.

Katharine: You might be interested in Cindy talking about the work that she did. I told you a lot about the work I did. I think it’d be really helpful to hear the work Cindy did.

Cindy: Are we talking about legal work or work with Women’s Place? Or the bookstore?

Rebecca: Both! We are focusing on custody though.

Cindy: Legal work… all gay stuff? Or, are you talking just custody?