Issue 1: Civics

Introduction

Over the past year, members of the Portland State University Art and Social Practice Program have been asking ourselves what a Social Practice Journal might look like. In a field that is already so expansive and interdisciplinary, how do we corral together a group of contributions with some coherence? What are the topics relevant to socially engaged artists? What type of writing is lacking in the field of social practice, both locally and more broadly? Beginning with these questions, various models were tried out finally ending in the publication you see today.

The Social Forms of Art Journal is a bi-annual publication focusing on creating thematic issues related to socially engaged art. Our approach is to offer a multitude of perspectives on a given theme, pulling in contributions from not only artists, but people across disciplines. Each issue serves as a sort reader, or conceptual lookbook, that draws together writing not just about socially engaged art, but relevant to socially engaged artists as a way of orienting oneself in a given theme.

Each Summer issue of the Journal is published in conjunction with Assembly, a sprawling, weekend-long conference that the Social Practice program holds at various locations in Portland, Oregon. For the 2018 iteration, we have chosen to look at civic institutions and have planned events at Portland City Hall, the Multnomah County Central Library, and Portland State University. Our inaugural issue of SoFA reflects the theme of civics as well. Essays and writings look at a diverse range of perspectives on civics and civic engagement, questioning access, voter rights, power and transparency. Contributors include artists, educators, prisoners, activists, and social workers.

In “Who’s Got the Power?,” artist Chris Cloud reflects on his day shadowing the mayor of a small city. By going to a baseball game and walking the streets, Cloud gains insight into how power is wielded, especially when the mayor’s only nominal power is to forgive parking tickets. Ben Hall, in “Erase, No Place For Us,” outlines the ways in which ex-convicts are disenfranchised within civic society, lacking the right to vote in many states. In “On Systems That Don’t Work for Us,” Lauren Moran talks with DB Amorin and Rachel Mulder about working within the field of developmental disabilities, and the many challenges it poses to people across the spectrum of ability. Their ongoing project Public Annex works not so much within this system, as proposes a new one, based on care, access, and a common interest in art.

Artist Roz Crews reflects on learning and poignant classroom moments in “Learning to Participate,” crystallizing an approach to pedagogy that encourages engagement and public participation. John Paul Young contributes two poems and a short essay about the erasure of homelessness in the United States, based on decades spent as a self described hobo. Homelessness, according to Young, is an experience of being stuck in the present, for fear of the future. Shoshana Gugenheim Kedem interviews artist Beth Grossman about her socially engaged projects related to civics, including Seats of Power, where she documented the seated butts of city council members in Brisbane, CA. History teacher Gerald Scrutchions writes in “Justice in History” about the need to re-evaluate the narratives we teach our children, based on his experience teaching middle school history. And finally, artist Lenka Clayton shares a list of questions she asks herself about her own practice as part of 20 Questions, an ongoing series where we ask artists to share a list of questions that they might ask themselves about their own creative practice.

One of the central questions permeating this issue is who is allowed to participate? This question is about not only how we engage with government and citizenry, but also about how we create (or fail to create) a sense of community and belonging. It is a question at the heart of Social Practice, as artists engage, create, subvert, and interrogate the relationships that define our social spaces.

We hope you enjoy this first issue and look forward to the next,

SoFA Editorial Board

The SoFA Journal is made possible by the dedicated efforts of the SoFA Editorial Board and through contributions by members of the PSU Art and Social Practice Program, community members, and many other willing individuals.

Editors: Spencer Byrne-Seres, Kimberly Sutherland, Eric John Olson

Graphic Design: Kimberly Sutherland

Web Design: Eric John Olson

Justice in History

People who seek to learn history should know the truth, Students who are required to learn history should know the truth. Educators who have a passion to instruct, analyze, and facilitate history should speak the truth. In the west the narrative has been watered down, shaped in heroism, led by White Anglo Saxon Protestant men who escaped persecution of their homelands. In their circumventing of cultural cleansing, these men were perceived to have discovered a new world. From this point we have heard the white patriarchal experience hundreds of thousands of times over. Independance, westward expansion, abolition, industrialism, etc. Great wars, wars to end all wars, cold wars, wars on drugs, and wars on terrorism. Indeed there have been heroes, people who will continue to be idolized for their leadership, noble acts, and overall ingenuity. There are numerous reasons to take pride in being American, of course. American citizenship allows us to freely state our critical opinions of government, and not be placed in reeducation camps. Being an American “citizen” provides the platform to approach education with a very critical lens, especially when addressing United States history and civics.

Remember how great it felt to learn about the first Thanksgiving? Proud colonists trading their knowledge and food with indigenous peoples in the “new world.” Traditional education indoctrinates students in the roots of Thanksgiving at a very young age. Before we can even read we find it important to understand the first story of the new heroes. Turkeys are drawn on construction paper, cut out and pasted onto additional construction paper. Back in the day you could even cut out feathers, paste them to a headband and portray the “Indian” being saved from the great interior wilderness of your homeland. This story is a first step in a deep abyss. It prescribes the setting for a host of single-perspective events that some people never escape from. These lies create a host of problems in which the only victims are the students themselves. Generation after generation are perceiving war as a necessity of heroism, and injustice of many as a mandatory sacrifice.

Without some events indeed our world would be different, slavery for example. American chattel slavery created the most wealthy country on earth, no doubt. Not just southern planters were invested in the slave trade, cash crops and purchasing of large swaths of land. Wealthy northerners were sometimes directly involved; there was an immense profit to be made at various levels of this multidimensional institution. Importing humans as property, exporting of goods, innovation, and manufacturing were just a few of those components. Therefore, saviors of the black Africans were liberating slaves in theory, but withholding their freedom in reality. Northern entrepreneurs were equal to their southern counterparts in their determination to profit from the institution of slavery. In this young land of opportunity and free market economics, flesh was the sacrifice. Inhumanity was the backbone, and violence the legacy.

Indeed it hurts to learn that our forefathers, for some, were equally the masters of our ancestors. Great urban centers on beautiful waterways were once sacred tribal ceremonial grounds. Lands seized by people who conquer for freedom, wealth and protection of a certain few. The story of these victors and conquerors, in its most glorious and docile form, has filled our textbooks and become the mainstream narrative learned by students in history classes throughout the past century. Yet it is not the whole story; it lacks important details which are not yet lost to us as a society. We have the knowledge available in our collective memory to fill in the gaps and teach the whole story, the many truths that have so often been neglected. We are at a critical juncture at this moment: a crossroads where we can choose to embrace and teach our story from various perspectives or continue our past traditions of ignoring one side, whitewashing our textbooks, and teaching our students only the story of the victors, thereby perpetuating the cycle of misunderstanding which bolsters our deepest societal inequities.

This is why it is time to revise our history classes, textbooks and strategies for building upstanding citizens. No longer can educators perpetuate our original narrative as a means of assimilating some while undoubtedly disenfranchising others. In this search for justice in history, everyone is subjected to stories that are seemly impossible, overwhelming, and unfair. Hopefully by understanding these stories, students begin understanding the various conflicts that are present in contemporary society. Sexism, racism, xenophobia, consumerism and an overall imbalance of wealth in america and worldwide are just some of the problems perpetuated by our dominant perspective approach to teaching history.

Because it is difficult to capture and teach all stories, there is no timetable in which this goal might be attained, if ever. Nevertheless, it is essential that the instruction is implemented with fidelity, led without fear, and asserted with an objective cultural lens. Justice in history will not trickle down from our policy makers or the Department of Education, instead it will be led from the trenches of education. Educators must set the foundation in creating upstanders who refuse to let our history repeat itself, or mold the future. Moreover, it is never too early for our youth to learn the truth, an acknowledgement that there are two sides to every story. A good and a bad, merged into one narrative. It is time to merge the good and bad into one narrative, and to tell as many of the side stories as possible, before they are forever lost.

Since the truth has been proposed, what does this look like in the classroom in which I deliver instruction? My students are historically underserved, various institutions including education have left them overwhelmed and disenfranchised. Like many of today’s youth, their perspectives are often narrow, provided via internet and entertainment. However, this lack of experience is broadened in my classroom due to the fact that my students are brown and black. Furthermore, attending an underserved title I school means that we often don’t have opportunities to take our work into the field for real life experiences. Unfortunately a majority of our learning occurs in the classroom, and interacting with the greater world online. Therefore, it is my continuous goal to provide curriculum and instruction that examines US and global history using multiple perspectives. Again, informing students of the entire story, good and bad. Text, which allow me to facilitate culturally relevant and responsive instruction include, Howard Zinn’s Young People’s History of the United States. Bill Bigelow and Tim Swinehart’s Peoples Curriculum of the Earth, and when appropriate news specials from news outlets like Vice. Intertwined in this work is also my personal perspective.

As a black historian it is my job to retell the stories from our past, and I tend to do so with passion, I am one of the voices that for too long was ignored. I draw comparisons from the past to struggles and conflicts of the present. I provide students an academic voice that will hopefully be utilized in a powerful manner as they mature into contributing adults. I often tell students the most meaningful successful individuals are those who possess strong academic knowledge, and an ability to articulate themselves in a calm decisive manner. Is this always executed perfectly? I wish yes was the answer, but that would be another false claim, again perpetuating the belief that life is perfect, similar to the story we create of the American Dream. I am only sowing the seeds, it will take much more than me working with students over one or two years. Highschool instructors and administrators must be actively involved. University admissions officers, human resources and college professors alike will need to step up and provide a space that encourages moderate conversation. A space where people learn to understand each other’s knowledge, or lack thereof. White allies, black allies, hispanic, asian and native allies will all need to be present. Last but not least, society will need to put aside politics, heritage and other divisive tactics such as entertainment and media. It is society’s obligation to take on this task, reversing the harm created when our “forefathers” systematized our various institutions, based on where good was obligated to conquer evil.

Gerald D. Scrutchions is a middle school Social Studies teacher in Portland, OR. His goals are to instruct students to develop multiple perspectives when considering events of the past and present. Further, Gerald sits on the Portland Public Schools Environmental Climate Justice, which was the first of it’s kind in the United States. He is a strong advocate of teaching social and climate justice as well as reforming the use of textbooks in classrooms that fail to consider injustices of the past, or impacts of man made climate change of the present and future.

Life: Through the Eyes of a Hobo

There is such widespread prejudice towards the homeless, a widely accepted prejudice. They have become a new minority group hated by everyone. To become homeless is akin to becoming a leper. They are look at as mutants, outcasts and derelicts. A people to be ignored. For most of them homelessness was forced upon them with no other options. Once a person is introduced to such a level of abandonment and hopelessness, it affects them, on a deeply psychological level. Substance abuse is a logical step for someone who has lost everything they care about. Too afraid to die, they live in the moment wanting the pain and sorrow to end. They become stuck in the moment for fear of the future which is as terrifying as death.

At the rate America is producing homelessness, there just isn’t enough programs to reach all those that need them. Society doesn’t make it any easier, imposing so many restrictions and boundaries on the homeless communities. It seems like being homeless itself is a crime, which encourages the populace to look down on and even resent those who are thought of as not human. It seems to me that the prejudice against the homeless population is encouraged on most levels of society. You may think otherwise. But this is my opinion based off my own experience, spending the majority of my life as a vagabond. I just want people to be aware and recognize, that the homeless are still humans deserving human rights.

We as a species have become disconnected from our mother the earth (from which all life on this planet has sprung!). We well as each other. In city life we live in such close quarters but we don’t even know our neighbors. Our community has no community. We are afraid of the wilderness and its common knowledge that people think dirt is harmful. If concrete doesn’t give way to natural vegetation we won’t have a planet to live on. This conquer and subdue the land attitude need to be reconsidered. Because the conquered usually end up dead.

The Unsung Homeless

The Down Trodden,

Outcasts and misfits.

Sociaty’s cast aside,

Vagabonds.

Stepped on,

Stepped over,

Stepped away from,

Forgotten,

Unacknowledged

And left to die.

Scavengers,

Striving to live.

Fighting for life.

Oppressed,

Disrespected,

And disregarded.

Polluted

And poised.

Ravaged by addictions.

Coincidence?

Forced vagrancy,

Arrested for living.

Insanity.

No help for those that cannot help themselves.

The truly left behind.

The derelicts and garbage!

The UNSUNG HOMELESS!

Fighting Against Life

I’m living off the scraps of a dying people.

Who fancy themselves conquerors.

Conquerors of what they cannot say.

The evidence is clear in cities of decay.

Unknown to the populace,

Of each metropolis.

They are all rebels at war, with the natural world.

Behold the cancerous concrete,

Street by street,

Eating up what could live and breath.

Black and gray but never green.

Unable to live in harmony.

All because of a terrible belief,

That humanity should hold dominion.

The pinnacle of evolution,

And that their only solution.

No other species is allowed in.

Only as slaves never as friends.

No silly animals can be intelligent,

Only trained as entertainment.

The silent screams of the indigenous.

What would nature say? Would we listen?

We, trained to be afraid of the wilderness?

Lines drawn to separate sides, a battle neither can win.

I’m just a hobo on the outside looking in.

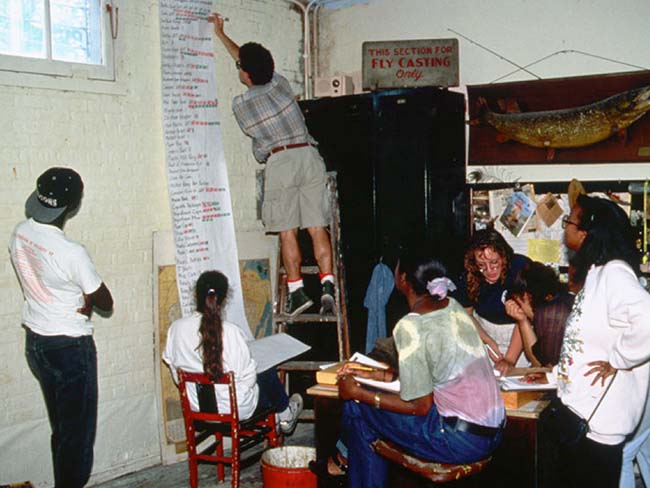

Learning to Participate

In August 2017, I founded the Center for Undisciplined Research, a nine-month art project situated within the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. The Center was meant to be a place for interdisciplinary research related to students’ interests. In the beginning of the school year, the incoming class of first year students collectively selected four main research topics: social justice, sustainability, music, and local cultures. Originally, I envisioned a structure for the project based on a traditional university center where the emphasis is on providing students and faculty with opportunities to practice interdisciplinary research and public engagement. As the year progressed, I realized that we didn’t exactly research any particular topic as much as we experimented with various ways to do and present “learning”; we functioned more often as a community of learners rather than a group of students with a “teacher.” Through the process, the collective established a force outside of the academic classroom where people came together to learn and practice new things publicly—maybe we became our own kind of citizenry within the university. Through this work, I am interested in breaking down the distinction between curricular and extra-curricular time to focus on what it means to be a participant within a community.

Since January 2015, I’ve lived in two different university residence halls as an Artist in Residence, where I’ve been working with first year students to think about how art relates to civic engagement. The intensity of my live-work situations has emphasized the relationship I see between education and civics—living my entire life between the walls of academic institutions surrounded by systems like: student and faculty governments; sexist, racist, ableist, and classist policies and procedures; the notion and consequences of tenure; controlled “common spaces”; false public space; condescending colleagues; outrageous tuition and crippling debt; lack of opportunity and resources; freedom of speech; depoliticized classrooms; and other civic structures upholding the current state of “higher education.” I’ve come to see my art practice as a tool for considering how and in what ways a university does or does not support the development of “engaged citizens.”

In the Reggio Emilia approach to childhood education, teachers document each student’s experience and progression using photography, note-taking, drawing, video and sound. I’ve incorporated this practice and other aspects of the Reggio Emilia approach into my work at the college level. This approach, in combination with the work of theorists like bell hooks and Paulo Freire, have helped me manifest my belief that students must work in collaboration with the teacher to create an atmosphere conducive to critical thinking and learning. Additionally, I’ve been influenced by practitioners of the Socratic method, archives from places like the Highlander Folk School (now known as the Highlander Research and Education Center) and Black Mountain College, as well as aspects of my own public education including my time at New College of Florida, my experience in the Art and Social Practice MFA program at Portland State University, and most especially, my committed teachers who’ve demonstrated the interwoven relationship between school, art, and life.

For this piece, I’ve recounted eight specific moments throughout my own education which call attention to the relationship between education, art, and civic life. I think this set of descriptions function together to explain how I arrived at the decision to make space for the Center for Undisciplined Research—a self-governing body of dedicated individuals, organizations, and teams that came together to explore the gray spaces between curricular and extra-curricular activities within a university community. I’m thinking about these moments as key memories that inspired me to think more deeply about how sites for education function as spaces where people decide how they want to engage with other members of their society. As you read through this essay, please consider the following quote from the exhibition catalogue written by Helen Molesworth, Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957 because I think it sort of sets a framework for where my mind is:

“Paul Goodman contends that when institutions and social roles become more important than the people who constitute them, humanity is suppressed to befit the system. Individuals must, therefore, disrupt the system to regain their humanity.” 1

1

When my painting professor told me there were no interdisciplinary MFA programs. 2008.

I’m not sure if my painting professor actually said this or if this is just what I heard as an obstinate twenty year old, determined to forge my own path. Regardless, this moment sticks with me because almost immediately after hearing her, I found out there are lots of interdisciplinary MFA programs out there. This interaction taught me to question the status quo and to seek out the information that I want to be true. It propelled me away from majoring in art, and it encouraged me to see what other interests I could pursue. During this conversation, my painting professor suggested that I check out a book from the library about Mark Dion—from her perspective, he was one of the only artists working in a truly interdisciplinary way at the time.

I remember seeing an image of Mark’s piece “On Tropical Nature” (1991), and I immediately felt connected to the varied “languages” present in the work. Within the project, I saw symbols and strategies from all the fields I was thinking about at the time—environmental science, archaeology and anthropology, art, ecology, and sociology. About eight years later I learned about his project, “Urban Ecology Action Group” (1993) during which he assembled a team from a local high school in Chicago to create a center for studying the ecology of a Chicago park, and I felt similarly transformed. Reading about this piece gave me a kind of hope that I could make work that was in conversation with other disciplines while continuing to be an artist.

On Tropical Nature, 1991. Source: http://www.tanyabonakdargallery.com/artists/mark-dion/series-sculpture-and-installation/41

2

When I spent two weeks at Mildred’s Lane. 2015.

After knowing about Mark’s work for several years, I eventually had an opportunity to

visit one of the largest and most collaborative installation’s he’s been involved with—Mildred’s Lane—which he and J. Morgan Puett founded in 1996.

The main house at Mildred’s Lane, 2015. Photo courtesy of the author. From

the project’s website accessed on May 10, 2018: Mildred’s Lane is a 96-acre site deep in the

woods of rural northeastern Pennsylvania bordering Narrowsburg, New York. It is a working

living-researching experiment centered on domesticity. The entire site is an art complex(ity)

open to anyone interested in programs and events that creatively embrace every aspect of life

in the 21st century.

I went there to attend a two-week workshop about social practice and walking as art which was co-taught by Dillon De Give and Harrell Fletcher, and during the trip, I felt like I was living in an installation. Being there was magical and it felt partly like summer camp, partly like school, partly like a party from the late 1800s, and partly like a long sleep-over. I was overwhelmed by the various ways I learned while I was there. Reading, walking, socializing, cooking, cleaning, organizing, talking, acting, public speaking, listening, swimming, and sitting quietly as learning. This was one of the first times I thought critically about how experiential education can unfold. The place and the pedagogy both feel inspired by Black Mountain College (as are many of the institutional educational experiences I’ve had).

Below is a description of Black Mountain College that feels especially relevant to my time at Mildred’s Lane:

“The mutability between art and entertainment, between work and play, was essential, not only because the mission of progressive education was to train democratic citizens capable of ‘the pursuit of happiness’ but also because it allowed for shifting positions between artist and audience. This fluidity suggested that making art was not an isolated activity, nor was membership in an audience a permanent condition. Rather the move between the two positions (actor and audience) was constitutive of the social fabric in which members have equal and rotating obligations to one another.” 2

Photo students at Black Mountain College. Source: https:/

www.thenation.com/article/the-weirdness-and-joy-of-black-mountain-college/

Being there also showed me how empowering it can be to work together with a team of people as part of something that is called an art project—something which is truly interdisciplinary. This was the first time I got to participate in a project that considered so many other disciplines as integral to its being. And it was really inspiring to be surrounded by fascinating artists from various countries and states within the US.

I’m thinking now about how this place contributed to my understanding of civic engagement, and I remember a really important moment when I was looking for a rolling pin. I was in the kitchen baking something with two other fellows, Pallavi Sen and Adele Ball. I looked around a little bit for a rolling pin, and as I was looking, Morgan walked in the room. I asked her where the rolling pin is stored. She asked if I had already looked for it myself, and then I said, “Yes, a little bit.” She responded, “If you had really looked, you would have found it. I suggest you look some more until you find it, and if you REALLY can’t find it, then I’ll be happy to show you were it is.” She left the room. I was startled by her assertiveness, and deflated by my own meekness. Eventually I found the rolling pin. This conversation made me feel a kind of urgency I hadn’t experienced before. I felt compelled to put my best effort into tasks before relying on someone else’s resources (in this case, Morgan’s time). This was an empowering moment because I realized I could probably teach myself almost anything I wanted to know if I was willing to put in the effort. And I felt reassured that if I did seriously need help, I had a community that would support me.

3

Swimming in a pool with snakes. 2009.

Tropical Ecology with Meg Lowman was one of the most influential courses I took during my undergraduate career at New College of Florida. It was an advanced level seminar in environmental studies, and I was a first-year student obsessed with sea turtles, pop-culture, and painting. I spent part of the summer before helping to collect data about Green Sea Turtle’s nesting habits in Tortuguero, Costa Rica, so based on that experience, I felt that I had satisfied some kind of requirement that gave me permission to skip any prerequisites for the class. I asked the instructor to join the class, explaining my reasons, and she agreed to have me. Everyone else was a junior or senior with a lot of knowledge about the environment and ecology in the region and beyond. For some reason, my out-of-placeness in this scenario didn’t bother me, and I joined the class with joy and appreciation.

After a semester of exciting experiments and experiences with the local environment, our professor invited us over to her house in the suburbs of Sarasota, Florida to have an end of year party. She invited a leading invasive species specialist, Skip Snow 3, to join our class for the event. He brought several animals with him to demonstrate some of the ways that exotic pets invade and destroy the local ecosystem after they are abandoned by their owners. As part of the demonstration, giant pythons were released into the fenced-in backyard pool area, and we were invited to swim with them. There was also a cake with snakes painted in frosting. I remember feeling totally amazed by Skip and his snakes. The experience was unlike anything I had ever done before—it was basically a pool party with invasive species masquerading as a college class. A lot of the folks who were in that class went on to become experts in various ecological topics, and even though I didn’t do that, the course taught me how to value experience as education.

4

Interviewing a stranger about their clothes. 2014.

When I applied to graduate school, one of the application requirements was to make a video of yourself asking a stranger about their clothes. As a lover of strangers and fashion, I had talked to plenty of strangers about their clothes in the past, but I had never documented any of those conversations through video. For the application, I decided to visit City Liquidators, self-described as “ample headquarters featuring an extensive selection of discount furniture plus home decor,” 4 in southeast Portland because I had been there a few times to buy props for work 5 and I was impressed by the sheer amount of objects filling the shelves. Without a doubt, I would meet someone interesting. I ended up talking to the owner’s wife who suggested that I talk to her husband because he had a reputation as a connoisseur of crazy socks. I spent an hour or so with the couple and their dogs in the back office. It was a really pleasant experience that was much more in-depth than any other conversation I had previously with a stranger about their clothes—a situation that would not have happened otherwise.

The process of actually doing something I might only have thought about doing if it weren’t for the assignment empowered me to dream bigger about what kinds of things I could do. It also helped me formalize the social, curious part of myself into something that I could utilize in my art practice. I started to see how my engagement with people might be interesting as part of my exploration of art. Since making that video, the process of claiming my curiosity and civic engagement as part of my work has emphasized the difference between doing something and thinking about doing something, as a motivating force.

5

Anna Craycroft’s Lecture at PNCA. 2015.

I was just starting my second year of graduate school, and I had only begun to scratch the surface of the question, “Why are you making this [artwork, book, essay, etc.]?” Anna Craycroft’s lecture at PNCA in October 2015 helped me see how an artist can create cohesive and concise projects while simultaneously being influenced by a variety of topics, experiences, and thoughts.

During this talk, she described some of her projects, but mainly, she explored out-loud and with images the lines of inquiry surrounding the artwork. One of the main things she discussed was the Reggio Emilia approach as it relates to a few of her projects. 6 This discussion got me thinking about how I learn, why I document my life so meticulously, and what it would mean to use the Reggio Emilia approach with adults.

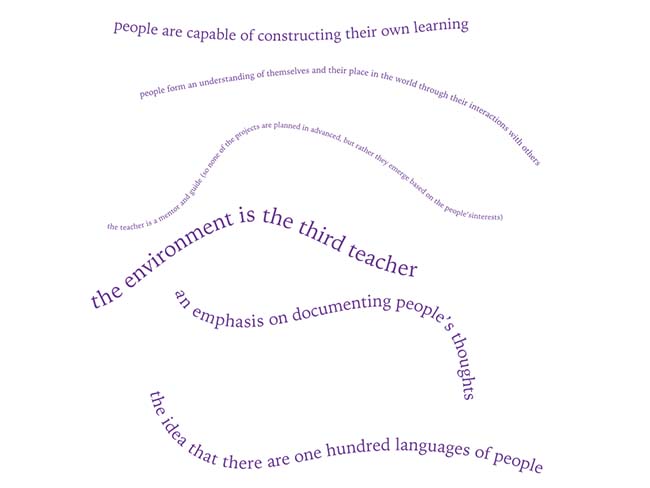

Core aspects of Reggio Emilia 7 :

– Children are capable of constructing their own learning

– Children form an understanding of themselves and their place in the world through their interactions with others (social collaboration)

– The environment is the third teacher

– The adult is a mentor and guide (so none of the projects are planned in advanced, but rather they emerge based on the child’s interests)

– An emphasis on documenting children’s thoughts

– The idea that there are one hundred languages of children

When I started thinking about the fundamental principles of the Reggio Emilia approach in connection to adult education, I saw clearly the links between education and participation in society. By replacing “child” or “children” with “person” or “people,” this list of principles functions as a nice blueprint for how to make a thoughtful, empowering, and generative civic space for adults.

6

When one of my students gave a class presentation about how inadequately my co-teacher and I were conducting the course. 2016.

The first time I taught a college course, I was a co-instructor with another teacher, and we were both very dedicated to establishing a horizontal learning environment where students felt responsible for contributing to the experience of being in the class. We hoped to make our classroom a space for exchange that could happen in any direction between everyone involved. In many ways, we were working directly in contrast with a more traditional type of classroom—we were working against a style of education that Paulo Freire refers to as the “banking concept of education.” 8

One day in the beginning of the semester, there was an event during which one student expressed that my co-teacher and I were not meeting their expectations of what should happen in the class. This student seemed to believe that we should be pouring meaningful, important, and otherwise inaccessible knowledge into their brain. The student expressed a desire to be a passive consumer, dependent on an economic exchange involving money and expertise.

I like to imagine water pouring in from all different sources, seeping into the cracks and crevices, absorbing into my permeable body—but not filling me up like an empty vessel. Image: Water Pouring into Swimming Pool, Santa Monica, 1964 by David Hockney. Source: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hockney-water-pouring-into-swimming-pool-santa-monica-p11378

This experience was a great reminder that some people disagree with how I want to teach, and it encouraged me to solidify my approach and vision so that I could defend my choices thoroughly in the future. Despite the difficulty of the situation, I became even more certain that I was on the right path, and I realized how much work it takes to shift a paradigm and to change expectations in the classroom. It also made me reflect on my relationship with government and local politics—if I could think of ways to effectively shift a paradigm within the classroom, I wondered if it would be possible to effectively communicate ideas with folks who disagreed with me in a more public sphere like the Neighborhood Association or City Hall.

7

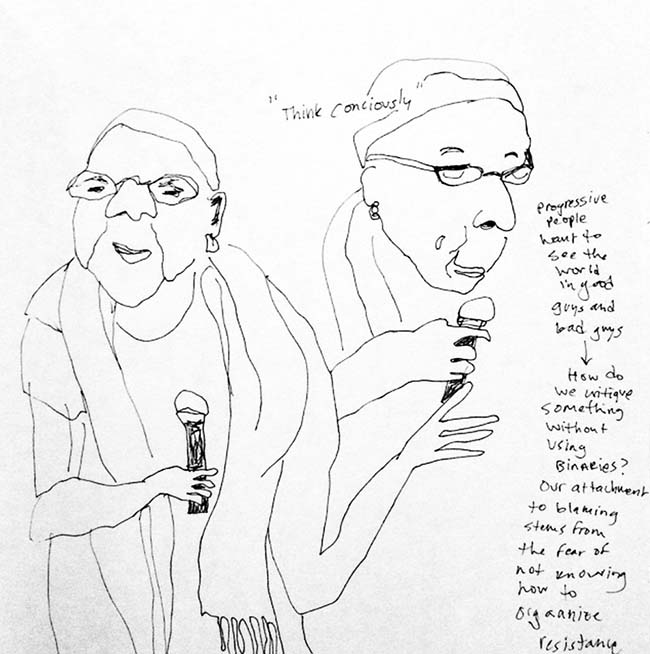

Having smoothies with bell hooks. 2012.

Four Winds Cafe at New College of Florida. Source: https://www.thoughtco.com/new-college-of-florida-photo-tour-788513

Throughout college, I worked at the Four Winds Cafe as a barista. This cafe, situated on campus, started as an economics student’s thesis project in 1996 and has continued as a student-owned and operated vegetarian restaurant and coffee shop since then. I was always inspired by the fact that a student created the cafe as a way to experiment with running a business, and I was even more excited to be at an institution where that type of project was not only allowed, but encouraged. In our life as cafe employees in the 2000s, we used it to experiment with cooking, and to host art shows, performances, lectures, special dinners, and other events. It felt like the cafe had its own civic life within the university, totally driven by students (even the director was required to be a recent graduate from New College).

Towards the end of my time at the university, bell hooks was embedded there as a visiting scholar, and she frequented the cafe. One day when I was working she asked me for a smoothie recommendation—I suggested the Bee’s Knees (almond milk, frozen blueberries, frozen bananas, honey, cinnamon, and vanilla protein powder). She tried it, and from that moment on, I felt connected to her. We often sat on the couches after my shift, just talking about life and love. We also served together on a committee of students and faculty that was organized to discuss and strategize ways to cope with the fact that there was a well-known white supremacist enrolled at New College at the time.

During this period, I fell in love with someone who was living in Oregon. I had one semester left in college, but I had all my credits and if I defended my thesis early, I could graduate early, and leave to live with my brand new lover in Oregon. Most people I talked to expressed concern about this idea—the idea of moving across the country to be with a person I only just met. But I knew how I felt, and I told bell about this situation. She encouraged me to follow my heart, so I did—almost immediately.

My casual experiences chatting with bell hooks showed me how influential and encouraging an academic person could be in an extracurricular way. At the time, I was an anthropology major with very little experience reading or thinking about theory, and I had never encountered bell’s work in a classroom setting. However, spending time with her made it so I could absorb some of her theoretical underpinnings into my moral fabric; our conversations made it possible for me to think about things in new ways without reading her texts. One day after knowing her for awhile, I saw her give a lecture, and I had a revelation about all the things I’d learned through talking to her. Her academic explanations gave context to my conversations with her.

Drawing by the author during one of bell hooks’ lectures at New College of Florida. Image courtesy of the author.

A few years later I started reading her books, and her texts got me thinking critically about how I facilitate learning environments—inside and outside of classroom settings. Making a productive space for education requires thinking and talking about how people engage with each other and how they make themselves accountable to the other folks in the room and beyond.

hooks has a lot of amazing things to say about the state of higher education:

“If we examine critically the traditional role of the university in the pursuit of truth and the sharing of knowledge and information, it is painfully clear that biases that uphold and maintain white supremacy, imperialism, sexism, and racism have distorted education so that it is no longer about the practice of freedom. The call for a recognition of cultural diversity, a rethinking of ways of knowing, a deconstruction of old epistemologies, and the concomitant demand that here be a transformation in our classrooms, in how we teach and what we teach, has been a necessary revolution—one that seeks to restore life to a corrupt and dying academy.” 9

Without bell hooks’ work (this particular excerpt is from 1993!), I might be afraid to acknowledge that my classrooms and the choices that I make within them are political, but because I can rely on her work and her spirit as the background for what I’m doing, I’m not scared to consciously make political decisions according to my own beliefs. Choosing to not talk about politics and social problems within a classroom context is just as political of a statement as discussing openly, so I think it’s important to be aware of what choices I’m making.

8

When Harrell asked, “How do you want to spend your time as an artist?” 2016.

Towards the end of graduate school, our professor Harrell Fletcher asked the group the question—“How do you want to spend your time as an artist?” Maybe he didn’t include “as an artist” in his original question, but that’s always how I’ve remembered it. This inquiry cracked open a lot of assumptions I had about what I might do as an artist. Suddenly I was free to spend my time anyway that I wanted, and I wasn’t bound to other methods, models, and approaches demonstrated by artists who came before me. At the same time, I could bind myself to ways of living that non-artists had established and followed for themselves. Everything felt so open, and I realized again how important it is to choose wisely and intentionally.

Right now, as an artist, I want to make time to think about how different and unique each one of these roses is. I took this photo at the Washington Park Rose Garden in Portland Oregon a few years ago, and I’m amazed looking at it now because I realize that while every flower in this picture is a rose, each one is completely different from the next. There must be hundreds of totally unique flowers here, and I want to carve out time to observe them all for their special qualities. But I’m not interested in doing this alone. I want my art practice to be a space for being together with other people, to view, to analyze, to describe the roses together—togetherness with a sense of urgency and responsibility.

I guess I hope that the civic spaces I encounter and participate in can function in an almost identical way to how I want my art practice to be. I’ve learned to inhabit shared space with a strong sense of curiosity, compassion, appreciation, and awareness—but I wasn’t born this way, I had to learn how to participate.

Footnotes:

1. Molesworth, Helen. Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957. Page 281. Yale University Press. 2015. “Leap Before You Look is a singular exploration of this legendary school and of the work of the artists who spent time there. Scholars from a variety of fields contribute original essays about diverse aspects of the College—spanning everything from its farm program to the influence of Bauhaus principles—and about the people and ideas that gave it such a lasting impact. In addition, catalogue entries highlight selected works, including writings, musical compositions, visual arts, and crafts. The book’s fresh approach and rich illustration program convey the atmosphere of creativity and experimentation that was unique to Black Mountain College, and that served as an inspiration to so many. This timely volume will be essential reading for anyone interested in the College and its enduring legacy.” This description comes from the Yale University Press website.

2. Molesworth, Helen. Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957. Page 46-47. Yale University Press. 2015.

3. Read this article to learn more about Skip Snow’s work: Revkin, Andrew C. A Movable Beast: Asian Pythons Thrive in Florida. New York Times. 2007.

4. Learn more about City Liquidators by visiting their website.

5. At the time I was working for a video production company as a producer.

6. Learn more about Anna Craycroft’s approach in this interview about her project C’mon Language with Sarah Murkett for MutualArt.com and the Huffington Post.

7. See the “main principles” of the Reggio Emilia approach here.

8. Freire, Paulo. “Chapter 2: Philosophy of Education.” Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 1968.

“In the banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing. Projecting an absolute ignorance onto others, a characteristic of the ideology of oppression, negates education and knowledge as processes of inquiry. The teacher presents himself to his students as their necessary opposite; by considering their ignorance absolute, he justifies his own existence. The students, alienated like the slave in the Hegelian dialectic, accept their ignorance as justifying the teachers existence—but unlike the slave, they never discover that they educate the teacher.”

9. hooks, bell. “A Revolution of Values: The Promise of Multicultural Change.” Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Page 30. Routledge. 1993.

Roz Crews is currently the artist in residence at the Working Library, a program of c3:initiative in Portland, Oregon where she is creating a temporary event space called the Conceptual Drawing Studio. During the 2017-2018 school year, she was the artist in residence at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth where she founded and directed the Center for Undisciplined Research, a nine-month public artwork and student-focused research collective sited on campus as a tool for people to critically examine what and how they want to learn. She makes collaborative and participatory projects which manifest in a variety of forms including videos, installations, publications, performances, ephemeral structures, and workshops. She wants to know where learning happens, and she uses her art practice as a platform to fnd out more about how art schools prepare artists (and more generally, how schools function to “train” citizens), ways to disrupt systems, and how people participate in society. She was the Artist in Residence at Portland State University’s Housing and Residence Life Department (2014-2017), a curatorial assistant at the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art (2015-2017), and she is a co-curator of the King School Museum of Contemporary Art’s annual International Art Fair as part of Converge 45 in Portland, Oregon (2017). She holds an MFA from Portland State University’s Art & Social Practice program, and a BA in Public Archaeology from New College of Florida.

An Interview With Beth Grossman

Shoshana Gugenheim Kedem sits down with artist Beth Grossman to talk about doors, seats, civics and conversation as an art form.

Shoshana Gugenheim Kedem: So, let’s jump to your work that’s specifically situated in politics and even more specifically in different forms of civic engagement. Let’s talk about what the first project was, and how that unfolded, and has informed, and continued to inform the work that you do. Like “The Bureau of Atmospheric Anecdata”, and “Washing the Wall Street Bull”, and “Table Talks”, “Seats of Power”, which are all sort of your more recent works. Not all of them, but some of them.

Beth Grossman: Well I think just in terms of where it started, I think that I was, even with the Passages Project, it was already happening there.

Shoshana: Oh, interesting.

Beth: I’m a really social, interactive person and there’s a lot of times I’ve wondered why did I decide to be an artist because the sort of stereotype is the artist that goes off into the studio alone to, you know. The carriage house or whatever, and comes out with a masterpiece. I’ve wanted to have my work be some kind of impetus for building community and creating conversations and making relationships and that kind of thing.

So, when I started my Passages Project, I was working alone in my studio, and it was super tedious. I was also leading this organization called No Limits for Women Artists, which is probably a whole other story I won’t go into that too much. But I was building a community of women artists around me at the same time as I was doing that big project.

It was my first really big project out of graduate school. I had worked in political theater at La MaMa Theater, doing set design, and some acting and dancing, in New York. I had done a lot of crossover theater work, then I went to graduate school in NYU in Performance Studies. My focus was feminist performance art, and political theater. The personal is political, you know, working from that perspective.

And my thesis was a really cool project called “Window Piece,” about fifty women artists who each took a week in a window of a comic book store, just on the edge of SoHo on West Broadway. Each of them had a week to do whatever they wanted as installations to address the nuclear war build-up, to all kinds of social-political issues. Some did more political things to greater and lesser degrees. And it was really “problematic” having a woman in a window, with the male gaze, and all that kind of stuff.

So I had a lot of theatrical background, and I wrote my thesis, and then I got out of grad school. I kind of had to undo all of that learning in some way, and figure out what my own path was. That’s when I started my Passages Project, and then going into my family and the narrative of that. Then building the women’s artist community at the same time.

Shoshana: Was that all in New York?

Beth: No. No, I had moved out here already, to Oakland.

Shoshana: Okay. In what year? Just to give a context.

Beth: I did my undergraduate in Minnesota and I graduated in 1980. As part of that I was an exchange student to Malaysia, and I studied shadow puppet theater. My focus was on how they used shadow puppet theater as a way to disseminate public health information. So the kind of educational, social-political tool, even though it was a traditional art form. So you can see it’s like, it was all kind of moving in that direction anyways.

I was always trying to find, as a kid, going back and forth, bridging between art and theater and puppetry, and then actually doing demonstrations, then moving into undergraduate, where that was my focus. Using art forms as education, public health and political propaganda. And then in my graduate degree, I was at NYU in Performance Studies in ’85 through ’87. That’s when I did my thesis on feminist political theater art.

Shoshana: Then you went west.

Beth: And then I moved out here right after I graduated in 1987, and that was when I didn’t have the Jewish community in California. I was just trying to figure out what I was doing here. I had started a graphic design business to support myself, which is what I had been doing in New York. I had a freelance graphic design business.

So I was doing that, and then I started the Door Project, but then I had this, as part of No Limits, the idea was that you would come up with a largest vision for yourself, something that you wanted to work for, and think about next steps, and how to set up support to keep going, and then you would get together with these women every two weeks. I was leading two groups, so I had a lot of … I kind of wanted to put the whole process, the support group process, to a test and see if I could actually pull off a really big vision.

So at the time, I had this idea that I wanted to bring my doors to Ellis Island. Given my lack of any kind of resume of shows and things like that, that was about as ridiculous as saying I want to have a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art, or something like that. It was huge. It was huge.

Anyway, I went out there and met everybody, and I put it together, and they said that they were into it. I wanted to use these old dormitory rooms that were not exhibition spaces yet, and then they said, it was the time of multiculturalism, and they’re like, “Don’t you know some Native Americans, and some African Americans, and maybe you can do a project on immigration with them”, and I’m thinking, ‘well yeah, but they didn’t actually immigrate here.’

Shoshana: Oh my God. I cannot believe they said that to you.

Beth: So I said, “Absolutely not. But I will do one on Jewish women’s immigration and family history.” So they agreed, and I had six rooms, six old dormitory rooms, and I invited six Jewish women artists to create installations based on different basic scenes that told the narrative of the immigration story. It was an amazing exhibition.

Shoshana: Did those women also create on the doors? Did they each do their own installation in another medium?

Beth: Yeah, they each had their own room, their own mediums, and I just gave the theme, like arriving in a country, continuing family tradition. I can’t remember them all. There were like six different themes, and each person got a theme to work on.

Shoshana: I’m looking at it now. Do you have more documentation? Do you have images of the work that they did?

Beth: Yeah I do. It’s not online, though. But I do have it.

Shoshana: You should put it up there. Okay?

Beth: Yeah, it feels like it was ages ago. For me, it wasn’t enough to just have a show at Ellis Island. It was like no, I want a dialogue with other Jewish women on this, you know? And the other part too is that, it was a really big deal to be that visible with, not just Jewish history at Ellis Island, but women, Jewish women’s history. And so that was in, I worked on it for five years, in 1995. I had to fundraise for it. It was a huge, huge project. It was one of those things where, if I had any idea of what I was getting into, I would have never done it.

Shoshana: I”m familiar with that experience.

Beth: I really have to say that was the beginning of my realizing that it wasn’t just about making art. I really wanted a conversation with my work.

I don’t think I got as aware of it until I came up against the changing economic times, in terms of … so my doors traveled for 12 years to museums all over the country. Every time they moved, it cost three thousand dollars, plus insurance, and they’d have to fly me out there, and the museums actually had some budgets. I had room in my studio. And as time has gone on since 1995, the economic situation for museums is tighter in terms of their budget. My space is tighter, and that’s when I think I became really aware of what I was doing.

What do I really, really, really want to do with my art? I want the conversations. I want to be building community. I want to be in situations where we’re mutually turning light bulbs on in each other’s heads, that kind of thing. Once I became clear about that, I really moved away from the large object making, that was the doors, or the Virgin Mary project, or even “The Sabbath Has Kept the Jews”, where I would … or “First Comes Love.” Now I have crates and boxes and shipping, and crazy stuff. I just got like, I don’t want to do that anymore.

So when I’m developing a project, the questions are, can I roll it up and put it under my arm and take it on a plane? Is the purpose of this work going to be able to have a low infrastructure but high impact? Will it allow me to set it up and create a situation or a space where people can be in a dialogue about issues that I care about?

Shoshana: Right. And you chose the latter.

Beth: Yeah, that’s the direction that I’ve come to in recent years.

Shoshana: So can you talk about what you call conversations? What has been the most meaningful and impactful for you?

Beth: Yeah. Well, I mean I think in a way, conversation has become my medium now. It’s interesting, when people ask me, “Oh, you’re an artist. Do you paint or do you sculpt? What medium do you do?” And I used to say, “All different mediums.” And now they’ll be like, “What’s your medium?” Ideas! I just hate when people ask me that. But somebody just pointed out to me the other night that no, your medium is conversations.

I’ve had so many. I don’t really know where to begin, but I think the biggest part is that listening is a key component. I talk about conversation so the other medium is listening. Because I think I just try to create a space … and I don’t even need art really to do it, but sometimes it’s just kind of, you know, it’s a way to get people to walk into a situation.

Whether I’m having an opening at a city hall, or at a community center, or a synagogue then the audience is actually invited to something and they come into there, into a space. They often think that they’re gonna stand around and look at art, and maybe have a glass of wine, and all of that. But usually I try to create some kind of point of entry where there’s going to be something that happens where they actually become part of the art and interact with each other.

Some of it is like framing a key question in a really, really open way, that I don’t even have the answer to. And there is not one answer, but it’s just gonna give people an opportunity to think, and think together, and realize their intelligence and creativity and having to put different things together, and different ideas together in some way. That hopefully, and this is the point of a lot of branding agencies now, that everybody wants these projects, which is funny because I’ve been doing it for so long. And back in the day, there was no funding for this. Now they want measurable outcomes. Then it’s not art, okay? Then it’s social services, or something like that. The art part about it is when you set something up and you have no idea what’s going to happen. And you’re unleashing something that it’s going to be a journey and an adventure. It might come up with nothing. You have to be willing for that too, you know?

Shoshana: Yeah, every week we talk about all of these things in our practice, as a cohort, wrestling with a lot of these things. Measurable outcomes, engagement, and all of those things. So it’s not unfamiliar. It’s a big and important conversation.

I’m curious about the civics piece, if you could pull out any project that you feel like – maybe “impactful” is not the right word, because they’re all impactful in different ways and they all have different meanings and reach different audiences to different degrees – but one that you feel that is current, or that you feel particularly drawn to. You can talk about what that meant, from a civics perspective.

Beth: I guess I’ll talk across three projects that I think they all led one to the other. I’ll start with “Seats of Power”. “Seats of Power” happened because I’ve been really involved as a community activist and an environmental activist in my town. At the same time, I’ve also been an arts activist organizer. And that’s been kind of one of the ways that I feel like I differentiated myself from the other environmental activists, in that I made relationships with our elected officials and our city staff.

Actually when we were deciding where we were gonna live, and the kind of life that we wanted, one of the things that I wrote on my list was that I wanna be able to walk into my city hall and have everybody know me, and be happy to see me. Nobody wants to see environmental activists at City Hall. Yet, I’m 100% committed to that role.

But what I did was, I came in as an arts advocate, and basically had to make a case, and kind of educate our city about why a really active and vibrant arts atmosphere was going to be important for the city, in terms of not just feel good community building but in terms of economics, in terms of real estate, in terms of schools, in terms of having a sense of place, an identity, and making it a place that people want to come to, and do business in, and stay. And so it was kind of a long process over the years, and then also lobbying them to make an art space.

I did all that through this idea that I proposed to our mayor – to do this art-sharing evening every year. It was kind of like a really well-produced talent show. I borrowed it from what we used to do in our No Limits group. When we would do our weekend workshops everyone got five minutes to share what they were working on. So this was way more formal than that but I got our city to allow me to do it and that created an artist community. And it also gave our community a sense of the amazing talent that people are living amongst – their neighbors. And it gave people a chance to connect. “Oh, yeah you’re the guitar player”, and “You’re the mosaic maker”and that kind of thing. “You do fabulous weaving; I want to commission something.”

It really made a sense to have everybody knowing everybody beyond the fighting that was going on in our city over this constant struggle against the vicious development that was happening. And is still happening.

Shoshana: How big is this city where you live?

Beth: Four thousand.

Shoshana: Oh, okay.

Beth: We’re right smack in the middle of the Bay Area, and we are on a mountain that is a county park, and it has three endangered butterfly species. It has some of the best views of the Bay Area. It’s ten minutes from downtown San Francisco. Also, part of Brisbane is the former San Francisco dump, which is an extremely toxic wasteland and now has radioactive waste. It was a Super Fund site. They want to force us to put in four thousand houses to help with the housing crisis in the Bay Area. But that’s a whole other longer story that’s kind of the back picture of what’s been going on since 2004 and what I’ve been fighting against for a really long time. It’s really weird to be in a situation of fighting against affordable housing which is not going to be affordable because it’s so toxic and because of what they’re going to have to do to remediate it. But it’s a really weird situation. And not on our watch do we want people living on that toxic waste dump. It’s really serious.

So, anyways. That was the context, and I started coming in and really showing that I was a person who wanted to contribute to our community. Not just try to stop development and argue with City Council. So when I would get up to talk about the environmental issues I felt like they listened to me in a different way because they knew of how much I’d done and contributed to the community.

And I have relationships with every single person in the City Hall. We all know each other by first names. That was my goal. It’s been fun. And when I walk in there, I almost feel like I work there even though I don’t.

Shoshana: Do you want to?

Beth: People have asked me so many times to run for mayor and do all this and that, and no, I absolutely do not want to. I’m way more effective on the outside, doing what I do best rather than try to read through all that stuff about parking spaces and all that.

So but anyways that was the context of how I ended up getting involved. And because I made all of those relationships our City Hall decided to renovate and when they were reopening it they asked if I would be willing to do an art show in the conference room as a way to kind of welcome people back into City Hall. And I said, okay sure. And I got this idea for “Seats of Power” because I’ve sat in that conference room with those chairs. And I thought, you know when I’m sitting in a forest and I wonder, if the trees could talk what would they say? I realized that these conference seat chairs had heard everything over all the years of Brisbane history and that those were the seats of power, and I had actually had the opportunity to sit in them, and that I wanted to know what they would say.

I had this totally goofy idea that if I could get the Council members to let me photograph their butt, I could turn them into chair seats of power. The thing that was really cool about it was, the most important thing about it was, again, not the art objects. It was going to each one of their houses asking them to bend over and taking a picture of their butt. I wanted to have them sit on the Xerox machine but that didn’t work out because some of them are a little too heavy and it would ruin the Xerox machine.

So we had to revamp, and I had them squish a piece of Plexiglass against their butt so that I could get a squished butt, because I wanted the view from the chair. But the best part was that while they were bent over, I asked them what it was like to be in power.

So, it was just so fun, and of course they just couldn’t resist making puns and jokes. Then the puns became the titles for their piece, or their butt, and I turned the photos into upholstery, and upholstered the chair seats. I had them up in City Hall.

I was thinking that I wanted to have a way to involve people to come into City Hall and see the new renovations. But also I wanted for them to have a sense that the City Hall is theirs and there’s a lot of people in Brisbane or in any city that have never walked into a city hall before. And also kids. And I wanted them to feel as comfortable as I felt. I thought that, ‘wow, isn’t it amazing that our City Council has not taken themselves so seriously that they wouldn’t participate in a project like this?’

I wanted the public to get a chance to both interact with the Council people but also to see what it felt like to sit in a seat of power so I had a red carpet and I had a throne. I asked the general public to come and sit one at a time in the throne, the seat of power, and to make decrees. To say what they wanted to see happen in their town and how they were going to go about it and the support they were gonna set up. Basically, I was asking the largest vision questions.

Shoshana: Like what?

Beth: A lot like the largest vision questions that I used to do through No Limits for Women Artists. But I wanted to give people a sense of their own empowerment. A lot of people would say, “I’ve been saying we need a dog park and nobody listens to me and nothing ever happens.” And it’s like, well that’s not how local politics work. You want a dog park, you get a bunch of people together and figure out how to make a proposal to City Council. It takes a lot of time and there’s a process. You have to learn the process.

So, I think that’s the other thing too, that I was lucky about. I figured out how to get people to support me and teach me and show me when I was a kid.

One of the first people that I met when I moved to Brisbane was the former City Manager and she became a good friend of mine. Through some other environmental issues, she coached me about the whole process of how to approach our City Council. It’s very formal and you have to play by those rules. There’s not a class in it usually, so I was just really lucky that she mentored me and was like, “Okay, here now, go talk to this person, go meet this one, and go take this one out to lunch.” I would not have known how to do all that stuff.

Shoshana: Right. It’s a whole language.

Beth: Yeah, and most people don’t speak it, so I was really, really lucky. And so what I kind of wanted my project to do was give people a sense of: ‘Come on into City Hall. This is yours. These are your representatives. Here’s the City Clerk, here’s the assistant to the City Manager. It is their job to walk you through how to do this. These are the people that you need to get to know. And I think that most people don’t have any idea about that. So I wanted to try to use my project to be an education vehicle and a point of entry into the City Hall.

Shoshana: Fabulous. Super inspiring. I actually wasn’t aware of that. I’m so happy to hear about how it’s been used as a catalyst for this kind of conversation and dialogue. It sort of deepens the whole meaning, and, quite literally, the power of the project.

Based in San Francisco, Beth Grossman has collaborated internationally with individuals, communities, corporations, non-profits and museums. She uses art as a creative force to stimulate conversation and focus attention on the environment, history and civic engagement – all aimed at raising awareness, building community and encouraging public participation.

Shoshana Gugenheim Kedem is an interdisciplinary artist, traditional Torah scribe and educator. Immersed in Jewish tradition and ritual, embracing institutional critique, inspired by craft and beauty, her studio and collaborative works invite participants into intimate and unexpected borderlands. Shoshana is the founding artist of Women of the Book which premiered at the Jerusalem Biennale 2015.

On Systems That Don’t Work For Us: Public Annex and Finding New Ways Together

When I think about the systems offered to people living in the United States by established institutions, I find myself frustrated with their lack of human-ness or recognition of what it means to be a whole person. Interactions are meant to be sanitized, ‘professional’, and access to resources or opportunities are based on privilege and positionality. It is becoming more obvious that the systems we are floating around in today were not designed with us in mind (by us I mean anyone who is not an able-bodied, heteronormative, wealthy white male), and we are given options to adapt. Often these options are inadequate and disabling.

Working in three different states in the Developmental Disability (DD) system over the last six years, I’ve learned a lot about how workers and those served by those structures are treated. There is often inadequate pay all around, complete absence of reliable transportation, scarce opportunities for meaningful work, physically restrictive or clinical spaces, and lack of respect for work created by artists. I’ve seen employees mistreated by the state and the management, and then they in turn flex the power they have to dehumanize or take agency away from the people they are working with. There is a ton of resilience, dignity and dedication brought by people on all levels, but it often seems to be swallowed up by the chaos and impossibility of sustainably being a whole human. In some places I’ve worked, I never felt safe to report injustices I witnessed for fear of losing my job, and I knew others felt the same. I don’t want to discredit the smattering of amazingly supportive, progressive and holistic programs out there, but they are rare birds and they are usually only one part of a person’s daily life, not all parts. Working with Public Annex, I’ve realized how we can change the game, functioning adjacent to this system, but distinctly separate.

There are many long, multi-layered stories about how Public Annex formed and why, but a general idea we talk about often is a dissatisfaction with the systems we have been offered to function within. We have created Public Annex in an attempt to work within these systems in a different way, and to build community together in small steps that we can manage in between our day jobs. We are trying to figure out ethical and good feeling ways of doing things together across the ability spectrum. We talk a lot about accessibility, and people often misinterpret what that actually means. It doesn’t mean simplifying things, or being reductive, it means creating multiple access points and flexibility in ways to engage.

In an article about Public Annex for Oregon ArtsWatch, artist and writer Hannah Krafcik used the phrase “alternative value systems” to describe what we are creating. That has really stuck with me. While functioning within these oppressive structures created by a capitalist, colonizing, nation-state, we are managing in small ways to create new methods of working. We do value things differently than the systems we are offered to participate in. We like hanging out together and are passionately supportive each other’s practices. We want to take care of each other beyond labor roles and build community. We hope to slowly influence institutions we interact with and create new ones.

I had a conversation with DB Amorin and Rachel Mulder, founding members of Public Annex, about some ideas, frameworks, motivations and foundational concepts that drive Public Annex.

DB Amorin: The impetus of Public Annex was to, like you just said, kind of subvert the prevalence of care within a contemporary art context, because we were/are all working within this really rigid social work environment where there are so many “rules” that are completely arbitrary and invented by the non profit industrial complex. Obviously there are protections in place for people that matter, but it’s also predicated on this weird hierarchical kind of system where there’s a “patient” and there’s a “caregiver” and there is this really clinical distinction between the two.

Lauren Moran: And there’s always bureaucracy and hierarchy created around labor positions like, I’ve been told in jobs that I wasn’t allowed to be friends with people and stuff like that, people are clients. I feel like it gets in the way of meaningful relationships and I’ve seen people set up in those situations act dehumanizing towards each other.

Rachel Mulder: Right, like your not even supposed to style someone’s hair. That was a rule when we were working, but it was never enforced…

DB: Because it was known we had a different culture at Project Grow. We made a stand and had to sell it saying that’s what they were buying into or had purchased.

L: Right, Project Grow was set up as a separate entity originally, very intentionally nonhierarchical (by social practice artist Natasha Wheat).

DB: But yeah, those types of directives are common within the care field, right? Because they want to maintain this like sanitized air of “professionalism”. It really destroys some of the natural, organically formed relationships that people create. If each person, in reality, had to eliminate their workplace as a place to gain relationships and form friendships? If you were literally told you were not allowed to be friends with people you work with, how many friends would any of us have? I would have zero. And half the reason I get employed is to make friends, at this point. That’s why I have so many goddamn jobs, I just want to have so many friends (laughs).

L: Right, I know, same, besides trying to survive. (laughs)

DB: You know what I mean? Really that’s what it comes down to. Then there’s this whole other portion of it, like this idea of what does it mean to support the artistic practice of people with disabilities? What are the existing structures of that? They are problematic as well and they’re problematic, in part, because the general structure of the art world, in terms of monetizing people’s practices, is problematic to begin with. It’s all hierarchical; there’s the artist, there’s the curator, there are these institutional leaders.

L: Right, and institutions often seem to benefit more than artists by being able to claim ‘diversity and inclusion’.

DB: It really robs a person of very much agency to begin with, let alone having to be forced into this category of “outsider art” or whatever it’s called. Public Annex wanted to address all of those things. How can we rethink disability itself? We try to reframe our thinking of it to see it as a spectrum instead of a black or white, yes or no kind of definition. Also, how can we reposition ourselves and what we do within the greater context of a contemporary art system that is wrong to begin with.

L: Yeah, the art world and the disability system are both functioning improperly in our opinion (laughs). And they seem threatened by the fact that we are critiquing them.

DB: But they also see us as necessary. One of the reasons we did form classes and do the things we decided to do was because we could, like you said, funnel money and resources away from those institutional systems into practices that don’t necessarily have to meet the same types of weird medical or institutional regulations that they fall under. Because of the changes in state funding, day programs have to seek these outside organizations for programming. And because (pause) they had to be told how to treat people. Someone had to slap someone’s hand and be like, “you can’t hide people in a warehouse and pay them less than minimum wage, so please go outside and mingle with the rest of the world!” (we laugh, but Oregon is one of the only states where sheltered workshops have been outlawed) Which is still not quite a right concept to function under, “let’s go out and into another person’s space in coordinated groups, let’s occupy different places.”

L: It’s still pretty stiff, every situation is ‘safely’ orchestrated, but I guess that’s the reality of functioning within that system.

……

I am interested in civic engagement, or civic resistance that is working towards building a new society, one where the starting point revolves around accessible systems and institutions built by EVERYONE. This may seem idealistic, given our current situations, but when I am in a workshop at Taborspace with the Public Annex crew and everyone is laughing and singing, or when Lawrence Oliver drives his remote control trucks through the Portland Art Museum or when we are all pulling mustard flowers together out of a garden bed or when Ricky Bereghost teaches a weaving workshop or when we sing karaoke, it feels possible.

Public Annex is a collective and volunteer-run 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in Portland, Oregon that provides accessible urban farming and arts programming, focusing on inclusivity of artists and farmers with developmental disabilities. Our mission is to break down systemic barriers that prohibit marginalized populations from inclusivity by building a community around accessible farming and art programming. Programs we offer include but are not limited to weekly art classes, urban farming, lectures and workshops, artist residencies and artist representation. Why art + farming? Both art and farming are trades in which there is not a single defined approach; they can be accessed by all. We believe that art and farming can act as forms of communication – forms that cross barriers of language, culture, physical and cognitive ability. These are our chosen entry points for the change that we strive to see in our society. We work to empower and connect people – of all abilities and mobilities, people who share a passion for art and/or farming – to learn from each other, find meaningful connections to “work” and define their chosen identity within society. We utilize the spaces of other arts organizations around Portland, Oregon and operate our urban farm project on the Side Yard Annex Farm to provide our programming. We believe that in partnering with other established organizations, we can further our mission of helping marginalized populations become included in communities and spaces that they have not historically been able to access. Learn more at publicannex.org

Lauren Moran wants to put relationships at the forefront of their artistic concerns. Creating interdisciplinary projects that are often participatory, collaborative and co-authored, they aim to experiment with and question the systems we are all embedded in by organizing situations of connection, openness and non-hierarchical learning. They are interested in developing sites for accessibility and are an active member of Public Annex. laurengracemoran.com.