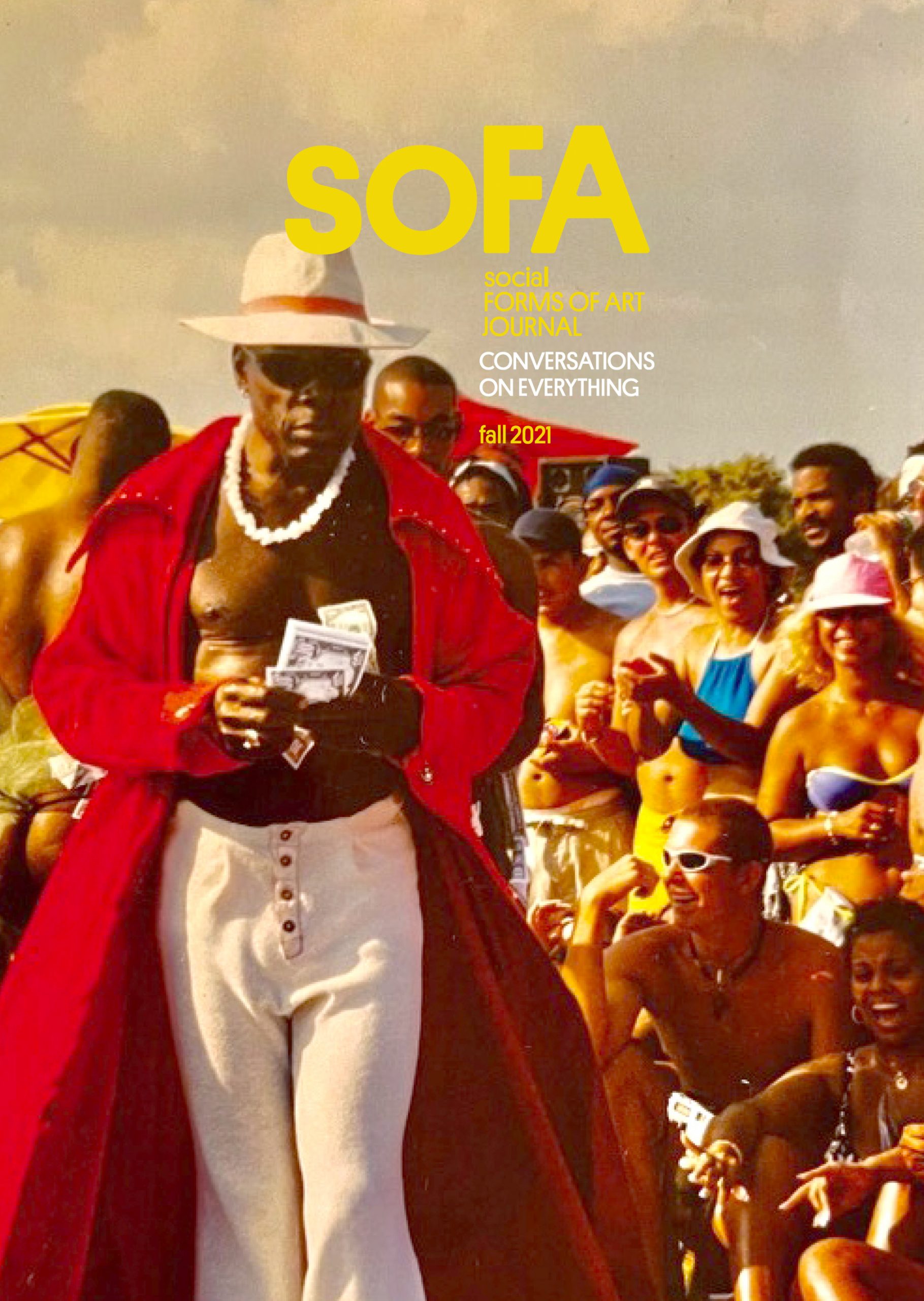

Conversations on Everything: Interviews Fall 2021

Letter from the Editor

A transcribed conversation isn’t always deeply revelatory, but it can be. In the participatory field of social practice, we honor the potency of dialogue and combined perspectives. If our art projects don’t take place in solitude, why should our research and creative inquiry? It’s only natural that conversation be a primary method; sometimes it’s even the artwork itself. For the socially engaged artist, conversation can be a hinge, a connector, a keystone, a debrief, a record. No matter what, it’s always a material.

In the Fall 2021 edition of Conversations on Everything for Social Forms of Art Journal, we share conversations using a traditional interview format, and approach the co-authored publication assignment as what I might call social practice praxis. As students in the PSU Art + Social Practice MFA program, we each come from different creative backgrounds and training, including: photography, design, dance, illustration, textiles, set design, publishing, curation, theater, herbalism, and cultural organizing. We find our way here because we’re drawn to the social component of our various disciplines, and we’re interested in spotlighting the parts of our artform that necessitate people, interactions, and collaborative contributions. We shift the focus from the picture (or the book or the play) to the process by which those things are made, and the people who work together to make them.

As a result of this shift, conversations become a significant and intentional medium for us all. “Social practice frames potentially ordinary or common actions such as dialogue and conversation,” first year student Luz Blumenfeld reflects. “It’s really helpful to understand that the things I do in my everyday life are a part of my work.”

That’s because a part of social practice praxis is formalizing what we’ve already been doing. Third year Shelbie Loomis offers, “Conversations and interviewing have been in the depths of my practice (existing in different forms, in different lives), but only recently, through reframing how I look at the act of conversation, did I realize how much…interviewing feeds my artform and practice.”

I relate to this as well. For years, I recorded conversations I had with friends and strangers, capturing the collectively-generated musings, theories, aimless chit chat, and impromptu laughs ping ponging between us to make sure they didn’t evaporate forever. The impulse was similar to taking a picture, and the result became an audio snapshot, which I could transcribe for my own amusement and/or re-perform as a script. Mostly, I put them on an obscure tumblr no one read, and assembled a semi-private album of memories that encapsulated the inherent value of people talking to each other. Many moons later, it’s thrilling to now have a framework to understand my instinct, integrate it into my art practice, and have the opportunity to channel it into a formal publication.

It led me to wonder how the practice of conversations and interviews is actively informing the broader work of my classmates. How has the practice of interviewing influenced their art making/thinking? In what ways are conversations valuable to their practice/s right now? How do they integrate the art of interviewing into their art practice? What did my colleagues find valuable in the process of conducting interviews for this issue?

For third year student Rebecca Copper, “an interview can open up space for exchange, to lean into an inquiry, to uncover, and to potentially understand. It’s a basis for questioning— questioning for curiosity.” That joint act of digging deeper together resonates with third year Mo Geiger, as well. “It’s a way of relating. Conversing is a trippy way to excavate something with another person.” Second year Laura Glazer agrees: “Having a conversation helps us figure out what we can do/make/explore together, and find shared points of curiosity and excitement.”

This exchange has the effect of expanding our practice and giving it artistic definition. “If conversation can be interview, material, medium,” Luz concludes, “it can also be research. And since I’m finding a lot of my practice to be research-based, it’s really helpful to understand that the things I do in my everyday life are a part of my work.”

For second year student Caryn Aasness, the interview gives structure to a familiar routine: “I think I’m always interviewing people, so it’s nice to formalize it. I always want to know what everyone is thinking and I love to try to convince them to think out loud. Or to work through on the spot something they have never really thought through before. Being sent into the world with ‘interview’ as an assignment really parallels the way I already thrust myself into the world with ‘interview’ as the imperative.”

The assemblage of these perspectives illuminates the utility of conversation as a tool for investigation, not only into our own subjects of interest, but into the importance of human-to-human exchange. In this issue, we hear from a scientist on his far reaching approach to mycology, a jazz professor on healing, a neighbor on her domestic art collection, a Ukranian immigrant on his transition to Portland, Oregon, the Bing Crosby Fan Club president on what it means to be invested, a librarian with a vision for collaborative learning, and much more. We hope you enjoy the material.

-Becca Kauffman, Editor

with contributions from Caryn Aasness, Luz Blumenfeld, Rebecca Copper, Mo Geiger, Laura Glazer, and Shelbie Loomis

Touch the Things, Make the Sounds

“I would love to have that integration of classroom space, studio space, and library space all in one. And that might be like a completely difficult thing to realize, but I think that I always want the library everywhere.”

ELSA LOFTIS

During my first year in the MFA program, I tried using an art studio on campus. I filled it with my favorite supplies, inspiring books, and uncluttered surfaces. But when I was there, it did not feel vital to my practice. I relocated it to another room with a huge window, hoping that it would be invigorating to see activity outside. Instead, the studio remained quiet and lonely, with few opportunities to respond to the place.

When Elsa and I talked for this interview, I was captivated by her vision of including spaces for art studios in the library, and I imagined relocating my under-utilized studio there. But even in my daydream, it still wasn’t a place I wanted to go. So, I started constructing a version of what a studio in the library might look like for me as a socially engaged artist: no walls, doors, or desks. Instead, there is a large table near the existing library study carrels and stools on wheels tucked under it. Nice paper and pens are available for free, and a special stapler for making zines is nearby. And anyone using the library is invited to sit down and work there. When we need inspiration or have questions, we can explore the books in the stacks and collaborate with Elsa.

This vision of a public art studio reveals an evolution of my creative practice, going from creating a private space that didn’t feel right, to envisioning a public space like the library as a studio space, and shaping it to respond to that site. This ideal place is not a space where I work in isolation. Rather, it is a large desk with space for me and other people to work, study, and create together; it is a place to be social in public.

Laura Glazer: I was trying to figure out a good place to start and what came to mind was how I’m haunted by something you said in our conversation last August. I have this really clear vision of what you described at OCAC(1), where you would have a pot of coffee and students would come in all the time. But at PSU, you were saying it doesn’t work at this scale. And you said, “I need help inserting myself into their practices.” Where are you with thinking about that?

Elsa Loftis: You know, I always feel re-invigorated when I’m able to do the instruction sessions because that’s when I start to get contacted by students. You know, when I get in front of them, and I do my little dog and pony show: here are the databases and this is why they’re so useful and look at all of the fun things you can look for and find. And then I will get emails after that from students who say, “oh, you visited my class and I’m doing this.” Then I get excited about the actual connection between working with people who are seeking information and hopefully assisting. And that’s the person-to-person stuff that I really enjoy. And that’s difficult because I’m waiting for people to kinda come to me. Whereas I would like to just sort of be out wandering around and saying, “Oh,” you know, “how are you today?”

I think very much about the library as place. The library is symbolic in many ways of a place for information. It’s a place to have solace and quiet and reflection, but there’s also kind of this element of, it’s a place to be. It’s a brick and mortar building and that is more or less important now than it ever has been.

I guess what I’m trying to say is, the library is definitely more than just what’s inside the four walls, it’s absolutely more than that. Not only because of our electronic resources and things of that matter, but it’s also kind of a headspace. It’s sort of a way to think, reflect, and work. But it’s also just the actual challenges of the proximity of where I am; in my past lives in other libraries, my office was sort of right out there where students were running around. So, if someone had a confused look on their face, I could just intercept them at their point of need. And where I am now, my office is in the cataloging and acquisitions space, which is behind locked doors so I have to actually physically leave my office to go look for students.

So that’s just a way that the space is elemental. And just having the energy of the people around me when they’re in their seeking phase of their research.

Laura: What does it mean to be an academic librarian?

Elsa: It’s a good question. It just means I’m a librarian in an academic setting. I’ve worked as a public librarian before, so that was a different experience. I mean, it’s not that different in a lot of ways. It’s a service orientation and you’re a public servant, you are meeting different needs in different spaces so you adjust your pedagogy or your workflow. You certainly are dealing with different kinds of collections. The range of people that you meet is certainly a little more narrowly defined in an academic library setting. Although most of the time we’re open to the public. Although we aren’t currently open to the public because of the pandemic. But we do offer spaces for the public to come in and share our resources and share our space. The PSU motto is “Let knowledge serve the city,” so we take that very seriously. We have that as an important role that we play, to offer information and services to people that are beyond our community.

And we also are a government document repository library. People need access to their government information and we provide that.

Laura: Where is the ideal space for you to work in? And it can be in a magical world!

Elsa: I think that in my magical world, the library is in the center of campus, in the heart of the physical space that students inhabit. I would love for there to be studio space in the library. In fact, I used to experiment with some of that.

I would try to put small little pop-up library collections in the studio spaces so that people could have reference resources while they’re throwing pots or welding things. [Laughs!] And when we did that, it was difficult to gauge the engagement with the resources, because a lot of times there’s no way to really track usage if it was just sort of like, Here’s some stuff you could look at it, you know, go nuts.

When you’re trying to work with students and getting folks to get engaged with your materials, you just throw stuff against the wall and see what sticks. We used to do those little pop-up libraries—these little mini curated things—and I thought that was really nice; I wanted people to be able to have access where they were. Not have to be like, Now I’d like to venture over to the library and look at some different examples of what I might be thinking about doing right now as I’m sitting here in the studio.

I would love to have that integration of classroom, studio, and library space all in one. And that might be a completely difficult thing to realize but I think that I always want the library everywhere. [Laughs]

Laura: That is a beautiful quote! “I want the library everywhere all the time.”

Elsa: Well, because I want people to feel like they own it. I think that libraries can be daunting spaces. When I talk about the library as “place,” that’s often very loaded, I think, for some people. I think of libraries as sanctuaries and places to explore and places to go on these adventures. And I think that maybe not everybody feels that way. I think that sometimes they can be sort of vaunted spaces. They’re sort of cold and quiet and maybe you don’t feel like you belong. If there’s one thing I want is for students to have agency over their library, because it is their library.

Elsa continued: We’re not here for any other reasons; we’re here for service. You want to humanize it, familiarize it and make it feel like their workspace, not as some sort of museum or a place where they aren’t supposed to touch the things or make sounds. That can be loaded in a way because I think the library as place is very important and I think that research can be done in so many different environments and formats. You can do a lot of research online; people are very good at doing research online. We’ve spent a lot of time here creating a lot of learning objects(2)(3) and ways that you can access materials virtually, and you don’t have to be in the library, but I also think that the space is important.

And again, that really depends on what kind of learner you are and how you like to interface with things. But I think one of the nice things, and especially for art students and art practice students, is that element of research that’s that really kind of almost haptic practice of research, like you get in there and you’re engaging with physical materials.

For some learners that’s really a big element for their practice, for their understanding: how you process things—physically and mentally—and work that into your creative practice.

And then there’s also that kind of iterative feeling of being in the lobby. You start… it’s like you search and you research, there’s this cycle. It’s not just searching, it’s re-searching. You keep coming back, you keep doing it again. And for some makers, it’s that kind of repetition.t’s that iterative process of research and it being a discipline, you approach it in a disciplined way. And that’s evidenced in a lot of different, physical practices of making art, too.

That’s what I also like to relate to people, is that the parts of the brain that you’re using when you’re doing research are creative parts of your brain. It’s part of art practice, too. You’re using those same kinds of problem solving connectors, the same little parts of your brain light up when you’re doing research as when you’re creating things. And I think that that’s a really useful way to look at it because it’s creative problem solving, just like you’re doing when you’re making work.

Laura: Where do you land on reframing the concept of research for a studio artist and a non-studio artist like myself?

Elsa: Well, it’s a really good question and it’s a really important issue. I think that all over the academy, not just in the arts, we are asking ourselves these questions and mostly from the library’s perspective: what do we collect and what voices are being centered; what voices are being left out; who is considered an expert in their field; what’s considered scholarship?

There are a lot of silenced voices in that narrow definition of what constitutes scholarly research and those definitions are opening up. We see this now and it’s our job as the library to be on the front lines of that and leading that, and collecting and valuing and centering—I don’t want to say alternative research, or maybe just non-traditional resources, I suppose—narrative things and people with learned experience and lived experiences, being thought of as experts, not necessarily attaining some sort of degree that makes them all of a sudden worthy to hear and listen to.

So, for a studio artist and a non-studio artist, I think that those paths are somewhat parallel. But it’s also difficult to wedge that into a traditional expression of scholarship. If you were doing a research essay and you needed five peer reviewed sources or X amount of primary sources versus secondary sources, and this is how you format your bibliography, it can be a little bit daunting to put this sort of non-traditional research into a traditional kind of scholarly product. I think that our instructors are more open than ever to that. You could speak to that better than I could. Do you feel that that is something that’s encouraged or at least tolerated?

Laura: I don’t know yet. I’m really taking my first class outside of the School of Art and Design this term in the History Department where I’m taking a class on museums and memory. We have to write a research paper, which I haven’t done since the nineties. [Laughs] So I am looking at the list of requirements, like six primary, secondary sources and thinking, huh, how can I bring the lens that’s relevant to me as an artistic researcher to this requirement? And I’m in a pretty good dialogue with the instructor. I want to be careful not to push her too far because I think she’s more traditional in how she approaches research papers and so are my classmates, but that doesn’t really work for me cause that’s not what I want to produce. I guess in undergrad, it was very traditional, very structured and I just didn’t do it.

Elsa: Well, you’re not alone in that. I think that we hear that a lot more and I think that that’s becoming more accepted. It’s not like, Oh, well, this student just doesn’t want to produce what I want them to produce. Even my son—he’s nine years old—his teachers are talking about, Okay, maybe you could make a video, maybe you could do a presentation rather than a paper or something like that, just being more inclusive to people with different learning styles or different storytelling. That’s been really central to a lot of more evolving scholarship, talking about things in terms of storytelling.

Laura: Definitely, which I’m always excited by and that’s the route I’m taking for my museums and memory research paper.

Would it make sense for a student to think of a librarian as a collaborator?

Elsa: Oh, yes. I hope so! [Laughs] Yes, because that’s how I think of myself. I think about myself as playing a supporting role. I love the idea of the librarian as a collaborator, yes. What that looks like in practice is a very interesting question, it can take a lot of forms. We’re in these roles as faculty, but we can do research together.

One of the things that I’m always trying to get to the root of is, how is that being engaged with, or is it being engaged with? And what can I do to better my pedagogy and my skills to share these research methods and these research resources and how can I do that better? I’m always, in a way, collaborating with students, whether they know it or not, to see how that’s going. Whether or not it’s a measurable outcome depends on how it’s being measured, I suppose. There’s traditional metrics of, We could give a pre-test and a post-test, or I can analyze people’s bibliographies to see if they found great sources or things like that, which is not really an active collaboration.

So, I’ve done things in the past where I’ve done focus groups with students, had them come to the library, tell me about what their needs are that we’re not meeting. What are we doing well? What could be improved? And again, trying to lend the agency to the students so that they have an active hand in creating their space, their library.

I’d love to collaborate with students on their independent projects, I think that would be wonderful. But mostly from my side, I am interested in collaborating with students to create a better library for them and a better learning experience for them. But I think it could happen on both sides.

Laura: When you say create a better library… I’ll tell you the vision that is in my head and it’s narrow: I think, Oh, get different books, more books.

Elsa: Okay.

Laura: Tell me what it means to you?

Elsa: It means community. I think it means an inclusive place where people feel welcome and where they feel productive. New books are nice but it’s also about active space and active engagement. There’s a few different ways to think about it.

More books, beautiful environments. Certainly, it’s nice if the chairs are comfortable and the colors are pleasing to the eye. But yeah, obviously the resources, the best possible resources that reflect our students’ needs and their interests, really inspire them and encourage their own growth.

Sure, the best possible library would be: you walk to a shelf and the thing that you were hoping for just pops right out. But what also is even better is that that thing didn’t pop out, but you got this other idea because the thing that was shelved next to it was sort of interesting. And so you pulled that out, and then you started walking around, you know what I mean? I love the serendipitous browsing, which is why we kind of create these cataloging systems where everything’s co-located.(4) So if you’re on the right track, you’re kind of on the right track. Sometimes that’s not true. Sometimes you gotta go to a whole different floor of the library if you want painting, but now you’re interested in aesthetics where you have to go down to the basement.

But that’s just the nature of the size of the collection, which is wonderful. You want a big, rich collection with lots of different formats and things kind of jump out at you in different ways. If you have the special collections, zines or ephemera or things like that, it’s just fun to kind of go through that stuff and get ideas. And then if you’re in the stacks, you’re kind of looking through the physical spines of the books and sort of getting the smell and all the physical and psychological cues that go with just sort of roaming around the stacks and having those kinds of serendipitous experiences. That would be the perfect library, I suppose.

And then you’d have a relaxing place to be, or where you were stimulated by all the cool stuff that was going on around you, where people were discussing great ideas. And then you’d have your studio right there and you could just go in and start working. That’d be pretty nice. Coffee wouldn’t hurt! [Laughs]

Laura: As a sidebar, I recently had that serendipitous experience at the downtown Multnomah County library and it was so special. I had to work for it, had to really pay attention to my inner voice, leading me around. It was triumphant and it changed my research path.

Elsa: Wow.

Laura: I’ve had that happen a little bit at the PSU library. It’s only been open for a little while, so I’m still finding my bearings there. So as you’re describing this magical library experience, the perfect library experience, I’m thinking of the different elements: in one way, you’re describing (in my mind), like a coffee shop and sometimes there’s a lot of activity and sometimes it’s really chill, without a lot of activity. And then I’m imagining a research lab for a scientist, like things bubbling over. It’s a really dynamic space, what you just described.

Elsa: I think the best libraries are, and it fits with our mission. But I also think that part of our other mission, just as important, is to collect and preserve. I mean it’s really important that we are keeping the human record, right? And that’s what we do. I think that a lot of what we do that is important, is curating a collection that is valuable and instructive to our students and also to the community at large.

And so we need to be very intentional about how we use our resources to provide those things. Resources are limited and not just in terms of budgets, but also in terms of space and our priorities and what we can provide. And that’s where librarians come in and use their expertise to get the best, most relevant information in front of a searcher– a researcher.

Laura: What’s informing you as a librarian, right now?

Elsa: In terms of what to collect or in terms of just how I’m spending my time?

Laura: Referring to how you collect, because you were just talking about that, the intentionality of a librarian. So that leads me to wonder: well, what’s informing your intentionality?

Elsa: We need to be responsive to the needs of our departmental faculty. So, of course instructors and professors will be telling us what they need to support their curriculum.

Another good indicator for me is when new courses come up, we are asked to write a statement of support from the library, so I get to see syllabi and make sure that our collections can support the teaching and learning endeavors of the new classes that are starting. So, that’s really wonderful for me because then I can see what’s being assigned. Certainly, I’m looking at making sure that we can support the assigned reading lists, but also just kind of getting a sense of where things are going in the departments. And so that is really informative to me.

It’s also informative to me when I’m in my instruction sessions, because I have an idea of what the assignments are, the research projects, working with students, finding out what they’re interested in and then that leads me to kind of explore. And maybe we don’t have everything that they might need and that’s when I go and I find it.

I also read a lot of academic book reviews, new things coming out by certain publishers that I really value or appreciate, but I’m also still looking for things that aren’t as well represented in our collection. We need to have a sense of where the gaps in our collection are, what might be overrepresented or underrepresented. Do we need another book about Renaissance painting, or are we more interested in collecting a new exhibition catalog about yarn bombing? I don’t know. [Laughs] It doesn’t mean that the other one isn’t useful and necessary. But where do we fit in the conversation and are we representing what’s going on currently in our students’ practice mostly and what’s being taught in the curriculum.

The other consideration we have is we are part of this wonderful big consortium. We have 37 other libraries from universities and colleges in our area that also have their collections and we share that catalog. So, we call that cooperative collections development.

While I might not need to buy everything… I can’t buy everything. But the University of Washington might have one and Portland Community College might have one. Reed College might have one. Willamette University just acquired PNCA (Pacific Northwest College of Art) and now their library collection is part of our catalog. They have some really amazing parts of their collection that might not be represented in the PSU collection, but I can get it.

So those are other things that are kind of informing my collection development and what I see as a need for our library. As wonderful as it is to have all the things on the shelves in the library space, where you’re looking and searching and having those serendipitous shelf moments, there’s no way that we can have everything on the shelf right in front of you. So that can be a frustration. People like to just go and browse and that’s awesome, I get that. But there’s so much more to our collections. They’re all over the region, they’re all over the world, and they’re in the online environment. And so some of those things do get missed when you have a researcher who just really likes to browse the shelves.

Laura: I read your article, The More Things Change: The Collaborative Art Library, and I’m a huge fan of the inclusion of “collaboration” in the keyword list. But I want to back up a little bit and ask you, does PSU have an art library and actually what is an art library?

Elsa: Ah, that’s a really good question. We have our central library; we don’t have any sort of satellite library. Some departments have their own collections, but they aren’t under the purview of the library.

But an art library you are basically focused on art but it’s not to the exclusion of everything else. I’ve worked in art libraries and it’s mostly to support a specific kind of learning activity, the study of art in this case. Museum libraries are much the same, they’re there to support the research of the curators or visiting researchers who come in and would exemplify a kind of collection focus that a museum has. The Museum of Modern Craft, when it was around, had its own library and those had obviously a very specific scope and focus.

At the OCAC library, we definitely built our collection around what was being taught in school, so the different kinds of craft concentrations, but also art history. And there was a lot of social history too, you know? Libraries take many forms and many shapes and the art library is not a monolith of one kind, but you would certainly find more art books in it. [Laughs]

Laura: Thinking about the art library: so PSU’s collection isn’t considered an art library?

Elsa: Well, it would be the art section of the library. Yeah, yeah, yeah, absolutely.

Laura: Okay. Got it. Cause as I was reading the article, I was like: oh no, are we not included?

Elsa: Oh my gosh, no, no, of course not. We have wonderful, wonderful art in our library. And I mean, an art library can be conflated to mean so many things. It could be a library of art, it could be a bunch of paintings lined up. A library is terminology that can mean any kind of collection, I suppose, as long as it’s organized and preserved in some way.

We use the Library of Congress classification system so most of our art books are in the Ns and they’re sort of located in a way that’s find-able and together. But other parts of “art” are not in the Ns necessarily. They might be in more technology-related things. So like photography will be in the Ts and aesthetics and the study of beauty and things like that are going to be in the Bs, which is more in the philosophy area.

That’s what’s wonderful about the multi-disciplinary part of that, and you can look all over the collection and that can inform your art practice, certainly.

Laura: When you think about yourself as a collaborator with a student researcher, what do you make together and what do you wish you could make together? We talked about maybe a bibliography, but what are some other things? I’m trying to really wrap my head around what that collaboration is like with you as a librarian or even with the library as space?

Elsa: Well, I think that one thing that was fun that I’ve done in the past with students at the Oregon College of Art and Craft Library has been for a guest student to curate a book display which was always really fun. We have had students do that in the past where they go with the theme and find things that they’ve connected with and arrange it in a way that’s pleasing or just accessible for people.

We’ve had people do art shows in the library, certainly utilizing not only the space, but also elements of the stacks and the books themselves. One example of that is, I had a student that made all of these really delicate ceramic books and he would kind of inner-shelve them in the space and it was really neat. We had students take over the space in a lot of different ways with their physical work.

Then rearranging the library space to facilitate other kinds of making and doing and even if it’s something as simple as having a knitting circle going on in the library and we would pick topics to talk about as we were doing that, readings that we all might have done, or just sharing favorite stories or something like that. I suppose you could mean a collaboration in that way. Students collaborating with the librarian themselves or with the space or just the different ideas of use.

We had one student one time who was exploring repetitive practice stuff and she put a big trampoline outside the library and she would go and be on the trampoline for at least two hours a day, not jumping necessarily, but she would be sitting out there or just being in that little space. That was outside of the library and certainly everybody else was welcome to use it, [laughs] and it was just kind of this fixture. It wasn’t necessarily anything that I was doing or collaborating with myself or even the space of the library, but it did take on a form of its own because it was this sort of feature that was happening and people would talk about it and she would start to try to help generate those conversations, too, because that was part of her inquiry.

I prefer the ones where the space is being used, reused, and remixed and the collection is part of that. And anything that people are using to connect. That’s what I hope for when I collaborate with students or have them collaborate with the space or the collection.

Laura: Anything being used to connect ideas? People?

Elsa: Yeah.

Laura: What are you meaning with that connection?

Elsa: I mean specifically people. Again, having ownership of the library, having agency, and feeling like they belong there and that the library can change to support them rather than the other way around, if that makes sense. Because when you come into the library space, you have to kind of conform to it in a way, right? You need to position yourself where you need to find the things and there are rules: you have to go to the circulation desk, you have a checkout period, you have a loan period. So there’s sort of these other things. But I think that the library can also transform and be a space that can be used and enjoyed and people can connect.

A really great example of our collaboration was with that subject guide that we created.

Laura: Yes!

Elsa: That can be a work in progress and it can be molded and shaped. That kind of learning object is really wonderful because I think that it fits a need and it wasn’t a need that I knew about until you told me.

That was a great example of a collaboration. It’s a positive step that now exists and it’s something that can continue to change and be added to. There’s a lot more things like that that we can do, I think, that I’d love to see students engage with and make it their own, in a way. I can’t exactly let everybody edit that guide, but I can garner all kinds of input and feedback about it and adapt and change and be agile enough to create new things out of it.

Laura: You mentioned including things in the collection that maybe aren’t in the traditional way we think of a collection being developed. And one example that comes to mind is publications by artists. How do you see those fitting into an academic library?

Elsa: You don’t mean like a monograph, you mean like kind of ephemera or like zines or…cause that can take so many different shapes.

Laura: I think zines are a good example. I’m also thinking about small press publications, things published that aren’t easy for an institution to buy.

Elsa: Right, right. Absolutely. Well, it gets challenging. We have the usual constraints of where to get it and how to collect it comprehensively, I suppose. And so it’s helpful if you wanted to have a concentration of some kind, like artists from Portland, for example, or an artist working in a specific kind of thematic area or medium or something like that. I suppose if we were to kind of pinpoint that sort of thing then it’s a little bit more scoped rather than just like, oh, you know, kind of anything we come across, we get.

Our special collection is a good place for some of this stuff, especially when the formats are a little unstable. Case in point, with a zine, I couldn’t really throw that on the shelf, it would get kind of destroyed, right? There needs to be a special place. And digitization of that kind of thing. Then that can go in our institutional repository, like PDXScholar, if it was somebody from our community, that would make a lot of sense. So there’s room for that and it tends to be kind of in what we think of as our special collections. Just for its own kind of protection, just physically, so it doesn’t fall apart.

Some libraries have very specific collections based on that. You know, ephemera collections, and postcard collections, for goodness sake! The New York Public Library has an amazing historical menus collection and things like that, it’s wonderful. It goes library by library and a lot of that has to do with the institution that it’s supporting.

Laura: I saw there was a faculty announcement that you are an associate professor.

Elsa: Oh no, I’m an assistant professor assistant. I haven’t gotten tenure yet.

Laura: Sorry, I mix them up. Do you teach classes?

Elsa: Librarians have faculty status at Portland State, or they can. We have faculty status and so we do teach, but teaching is defined as provision of library services. So our kind of pedagogy is providing information. We do teach, I teach instruction sessions. It’s kind of defined as, provision of library services is what teaching is, which means that we are providing the ability to do the research; that is our process.

Well, how is this going to look? What is the theme of this journal?

Laura: There is no theme for this issue. I bring the theme. For me, my practice is about books, collections of knowledge, selecting pieces of knowledge, libraries as spaces, people as collaborators. When we talked in August, I was like: oh, Elsa is a great resource. I need to understand more about what you do.

There’s a woman in Montana who does a traveling bookstore. And she goes all over the country and she comes to Portland. So I’m thinking about interviewing her in the winter. Kind of along this theme of books as spreaders of knowledge and trying to figure out where do I fit? Why is that a part of my practice? So, that’s why I’m talking with you. I’m like, why am I so drawn to the library, books, and collecting?

Elsa: I love that idea of the traveling bookseller, that’s really neat.

I had a colleague at OCAC, she’s at Reed now, she’s a book artist, Barbara Tetenbaum. And she was doing this really cool project where it was called The Slow Read and she was using Willa Cather’s book My Ántonia and she had these display monitors up in various places, and in different cities, too.

It would be just a display of one page of the book. And so people could kind of come and read that page. And then the next day there would be a new page. The idea was sort of like this community read, but also really slowly.

Laura: At the library?

Elsa: We had one of the monitors up at the library. But she went out all over the place and it was centered in Nebraska, because that’s where the author was from.

Laura: And she’s at Reed College now?

Elsa: Yeah. She and I used to teach together and she’s wonderful.

Laura: I’m looking at the website right now.

Elsa: Oh yeah, you got it? Okay, great. That puts me in mind of what you’re talking about, right?

Laura: Yes!

Elsa: Yeah. Pretty neat, huh?

Laura: Oh, my goodness. Where did you teach with her?

Elsa: At OCAC. She was the chair of the Book Arts department. Yeah, and then she and I co-taught a student success class for incoming freshmen. It was basically like a college skills class. I think we called it College Skills or something like that. But it was me teaching research and then also just how to be a student and how to succeed in school and even like financial literacy and stuff like that.

So she and I became good friends because we designed the whole course together and she was in the middle of this whole project in the last year that I was there and I was so blown away. You know, talk about collaborative and text as experience, right?

Laura: Oh my gosh. Text as experience. Did you just make that up?

Elsa: I just made that up and I don’t know, [laughs] maybe it flew in from somewhere. She’s one of those people that’s really quite amazing.

Laura: I’m going to have to spend some time with this. See, I already benefited from talking with you! I would not have known, oh my gosh!

This issue of SOFA Journal won’t come out until mid December, I think. And I will keep you in the loop. And just so you know, I personally publish it as a printed zine. And lucky you, you’ll be a lifetime subscriber. So you’ll get a copy of every one that I do in the next year and a half. And then I’ll also send you the back issues.

Elsa: Well, they’re beautiful. I’ve been looking at them on PDXScholar. I’ve never seen a physical one, but I’ve been enjoying looking at them, they’re so rich and pictorial.

Laura: Awesome. Thank you so much for your time.

Elsa: Have a wonderful weekend!

Laura: Thank you! Bye!

Footnotes:

(1) Oregon College of Art and Craft was a private art college in Portland, Oregon, from 1907 until 2019 when it terminated all of its degree programs.

(2) A learning object is a digital, open educational resource that is created to assist in a learning event. M, Vanessa, and Jane C. “What Are Learning Objects?” Instructional Resources, October 15, 2021. https://blog.citl.mun.ca/instructionalresources/what-are-learning-objects/.

(3) From Elsa: “I was specifically talking about the Library Guides and from our website, Subject, Course, and How to Guides, which are created by Portland State librarians to help you! These guides provide helpful resources, strategies for research, and tutorials.”

(4) Co-located means having multiple things located together—like the sections in a library—the painting books are near the other painting books, Portuguese language books are next to the other Portuguese language books, and so on. Definition provided by Elsa Loftis.

Laura Glazer (she/her) is a student in the Art and Social Practice MFA program at Portland State University. She graduated from Rochester Institute of Technology with a BFA degree in photography and lives in Portland, Oregon. Her curiosity about people and the visible world guide her as she uses research, conversations, and collaboration to create projects. She processes and organizes research through publications and local, free distribution methods of printed matter and visual culture such as brochures, flyers, and postcards. See her projects and process notes on lauraglazer.com and Instagram.

Elsa Loftis (she/her) joined the Portland State University library faculty in 2018 as the Humanities and Acquisitions Librarian. She is the subject liaison to the College of Art + Design, and the Film Studies, World Languages, and Literature departments. Prior to her arrival at PSU, she was the Director of Library Services for the Oregon College of Art and Craft, worked as the librarian for Everest College, held positions at the Brooklyn Public Library, the Brooklyn Museum Library and Archives, and the Pratt Institute Library. She received her MLIS from the Pratt Institute, and her BA in International Studies at the University of Oregon.

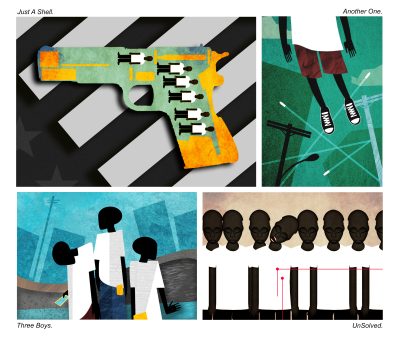

They Call Me ‘The Mayor’ at Riis Beach

“I wanted something for you to see that you hadn’t seen before. And to have a good time, and feel that you’re part of it.”

RALPH HOPKINS

Riis Beach, known for its history as a gay destination for sunbathing, swimming, and community, is a short walk from my apartment on the Rockaway peninsula, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, in Queens, New York. For this issue of Social Forms of Art Journal, I interviewed Ralph Hopkins, who they call The Mayor at Riis Beach. Ralph is a 73 year old native New Yorker, former chef, gold medalist for the Lindy Hop and Jitterbug, and a US army veteran. An elegant man filled with pizzazz, he described the beach parties and interactive fashion shows that he threw at Riis Beach in the ’90s, as well as his personal history marked by six decades immersed in the scene at Riis. We discussed art making at the beach, creativity with the queer community, and fashion shows as a socially engaged form of art.

While living in Rockaway, I have been on a quest to learn more about my dwelling place. As a native New Yorker, my connection to Rockaway dates back to my ancestry, with visits by my grandmother, Gilda Selby, in the early twentieth century. As a queer artist and herbalist, I have been researching queer ecologies and geographies, focusing on beaches. I have been engaging the intersections of nature, play, stories, and sensory experiences to explore queer possibilities.

Ralph, his work, and the history that his life expresses has been a great gift.

The following conversation took place on November 2, 2021.

Gilian Rappaport: Will you tell me a little about yourself? Where are you from?

Ralph Hopkins: I grew up in Greenwich Village in Manhattan… A lot of my friends don’t know, but I went to art schools in Newark [New Jersey]. When I was younger, I thought I was going to be a commercial artist. Come to find out, my mother and I end up having a little restaurant in Newark. It was called Bernice’s Snack Bar. So I worked there as a cook.

Gilian: Was your family in the restaurant business?

Ralph: No. Prior to [opening the restaurant], my mother was a beautician. My grandmother was a beautician, my cousin was a beautician. The beauty parlor was in my grandmother’s house that she owned, on the ground floor. My mother got tired of it, so she decided to open up a restaurant.

Gilian: When did you start throwing parties at Riis Beach?

Ralph: In about 1994, I was on Riis Beach with my friends, and we were saying maybe we should have a little party or something. Just as friends— everybody brings a drink, food, or something like that. Everybody will come in white. That would be pretty on the beach. So I thought, Okay, let me get to work. From then on, it was always the third Sunday in August.

Gilian: Will you tell me about the decorations? Did you do them yourself?

Ralph: Yes. I said, I have to do something to make it nice for everybody. I’d like to make the party look as nice as possible. I knew this area [in Manhattan] where they sell these discount toys, things like that, down the street from Macy’s. I went there and I bought like two dozen hula hoops. Then I looked up a balloon rental place on the East Side of Manhattan. I rented the balloons with the machine that blows them up. So the day of the party, I brought the hula hoops [and] I buried them halfway in the sand, so only half would stick out. And I tied the white balloons to each hula hoop so they would float in the air. To make it look pretty. And we brought food, and I cooked a little food. My friends bought drinks and food also, it was a little small table. And I brought my little boombox, and we had some music. We had a nice time, and everybody said, Wow… Other friends around saw and wanted to join. They said, Oh, well next year we’ve got to do another one. We had so much fun.

The next year was a white party again. Only I did it much bigger. The second party was at least, I would say 75 people. Then beach people started to notice. At the beach, they said, “What kind of party is this here?” To make it sound nice, I said, “This is my birthday,” so they would be more lenient. Any drinks, we kind of hid in the cooler. A couple of friends started to put my parties on the internet. I said, Oh my god. I was getting a little nervous. I said, I didn’t know it would get big like this. So I said, I got to up my game with the decorations.

So I had to get into my art mood… I went to the lumber place, and I picked up six 10-foot poles. They could barely get in my living room, so I tilted them in [there]. And I went to the fabric store and I got yards of fabric. It was only a dollar a yard at that time. I would have the fabric from the top of the poles come all the way down right into the sand as decorations. And I also had this ribbon that I got at this warehouse that a friend of mine worked at, luckily. Everything was like falling into place. And this warehouse, as I walked in, I felt like I was walking into a wonderland. All these treasures, everything is in this place. He said, Go take what you need, what do you want? It was stuff that companies would donate, they didn’t use anymore– restaurants, and whatever.

So I found my runway, it was a mylar fabric that coiled. It looked like you’re walking on water. Which I still have, the runway. I found this glitter ribbon, which shined like diamonds in the sun, like real diamonds. You could see it from across the bridge coming to the beach, that’s how they shine. So I added those to the top of the poles as decorations. Then I had to rent some tents. For the first party, we made our own tents. Through the years, it got bigger and bigger. I had to get three more tents– real tents– for the models to change. And I had to get a permit, because I had a DJ– music, the DJ, and I had a generator, everything.

Gilian: So the parties would happen once a summer?

Ralph: Always the third Sunday in August.

Gilian: And did you have a name for them?

Ralph: Well, it was “Ralph’s Beach Party.” And then every time I had to get the permit, they said I had to give a company name. I can’t remember what I said at the time. And they said, “Okay your name.” I paid them, it was $50 for the permit to have these big tents on Riis. They told me “If you have music, speakers, or a DJ, you have to have a permit.” Luckily, I was really friendly with the guy who was the head of the permits. He said, “Okay, Ralph.” Every other year.

Gilian: Did you have any fears when making these parties?

Ralph: The main thing that made me nervous was the weather— I couldn’t cancel the party and reschedule if it rained because I was working! And the food was already cooked, and I couldn’t do that again. Luckily it never rained at any of my parties!

Gilian: Where did the clothes come from?

Ralph: I found friends of mine who were students at FIT [Fashion Institute of Technology]. So I said, “Would you like to be one of my models?” And they said, “It’s fine, sure.” One friend of mine worked at FIT, and he said, “I can get more models for you if you need,” and he’d bring me the clothes. I said, “You never know if somebody will buy your things, you never know who’s in the crowd.” So they donated their time and knew other students that had their own clothing lines, so they donated their time too. I had like four or five different designers. Through the years, it got bigger and bigger. The main designer was my friend Everett Clarke. There were other friends of his, students at FIT. They would design outfits you had never seen before.

Another designer was named Wa Renee. That was the name everyone knew him as. He died years ago. Like a male Grace Jones. Very out there, very futuristic clothes he used to wear. Very famous in the community.

Gilian: Would you say it was mostly the same community who was hanging out at Riis Beach at that time? Or was it other people from the city who were coming there?

Ralph: Basically, people would come out to Riis, every week, every day of the week. But then after the word got out on the internet, they were coming from DC, upstate New York, and other places that are out of New York. And the Bronx. People were bringing me gifts because they thought it was my birthday party. People were coming up to me and saying, “Oh, happy birthday Ralph, happy birthday.” I said, “It’s not my birthday, my birthday is in May.” Memorial Day, May 30th. But I would tell them, I’d say, “Okay, nobody can say I can’t have my birthday party months later. So this is my birthday party.” So that’s what I did. I never even met these people that would bring me… I mean really nice gifts and stuff: bracelets, vases– which I still have. And some gave me some money, which shocked me.

Gilian: Because they wanted to thank you for throwing the party?

Ralph: They would come up to me and say, “Thank you so much.” Even up to this day they would say, “You know, I met my girlfriend, I met my boyfriend at your party.” “Your parties were so good, I had so much fun.” Everybody was nice. I never had any fights. Everybody was really nice.

Gilian: What was a typical run-of-show like on the day of a party?

Ralph: My DJ would come, the show started at three o’clock. Sometimes he would come a little late, like 3:30 or 4:00. When he came and set the music, he started playing as we’re putting down the runway. The models were in the tents getting ready, I’m getting ready too, because I opened. At the first parties I would close the fashion show too, with a show that I would do.

Gilian: What was your show? Were you dancing, or walking?

Ralph: I walked. I did Goldfinger by Shirley Bassey. She’s one of my favorite singers and I’m a James Bond fanatic, and I love Goldfinger. So I came out in all gold. Complete sequin gold. I was in a sequin gold bikini, my body was gold dust all over me, gold mask. I had six guys that I wrapped in gold mesh. They came out before me, like as the music started. And they would have in the fist of their hands, gold dust, which I still have some of that. And I told them, “Hold it in your fist to the very end. You will spray the gold dust all over everybody in the crowd.” I would come out in the middle of them, and I would touch each one of my dancers, while the music’s playing Goldfinger, because I’m Goldfinger. Another one, I came out as a… I was like a pimp. And that was to the music, “Money, Money, Money.” [singing] Money, money, money, money. And it was a coat with a long train. And I had a pimp hat on. And I had a fist full of fake money and real money. And I would throw the money into the crowd. And they were scrambling for the money, you know. It’s for fun. And I had six other dancers in that one. They would come out before me and I wrapped them in green mesh. And connected to the mesh was dollar bills all over the body. They would go out and I told them to face the crowd. They would just hand out the fake money, the fake dollar bills to the people in the crowd until I came out.

Gilian: Why was this at the beach, as opposed to somewhere else?

Ralph: Like I said, the first party, I just said to myself, You know, I want to have a party out here. And I wanted to have it in August, the end of the summer. At the end of the summer everybody will have their deepest tans. And your body will look really pretty. So I said, “Everybody come in white.” With your nice golden tan on your body, with the white bathing suits, and the girls bathing suits, the guys will look really pretty. White balloons and everything. And when they said, “Do you want to have another one?” I said, “Okay, one more, we’ve got to change the color.” That’s why we moved to red, blue, and neon.

Gilian: But always one color?

Ralph: That was the thing. I called it the color code. If the color code was blue, it was shades of blue. And we had another that was called Circus by the Sea. I had my friend, he’s a very good designer. I would say, “I need a ringmaster’s hat.” So he knew how to make that, he made the hat. He made a big ringmaster’s red coat. We had to make that in my hallway because it’s so big. With a long train.

At a fashion show you want to see really exotic, beautiful things that you’ve never seen before. I wanted you to know that I knew you were coming. I wanted something for you to see that you hadn’t seen before. And to have a good time, and feel that you’re part of it.

Gilian: Why is that important?

Ralph: It makes people want to come back for more, they want to see more. See something you have never seen before. You know? I’ve always liked dressing up, even when I was small. I love fashion. People who know me now, the clothes that I wear, you don’t see that with regular guys. The way I put it together. I don’t do it to show off. This is me, that’s just how I am. I like different things. People see me and ask me how old I am. No one can ever believe I’m 73.

Gilian: Did you realize that we are both wearing fleece today?

Ralph: Oh! I didn’t even notice that we matched.

Gilian: It seems like you were born with a sort of innately radiant sense of style. WIll you talk a little about style in your everyday life?

Ralph: When I sit on the beach, they walk up to me, [and they] notice my necklaces, my stones. I get a lot of compliments there. I wear it because it makes me feel good and has good energy. I’ve been doing this for many years with stones. People know me for my stones.(1)

Gilian: What is your setup like at the beach on a regular day?

Ralph: I only have my king-sized white sheets. I’m the only one. Been doing it for years.

Gilian: The beauty of a simple white sheet.

Ralph: I feel confined in a chair. I like to stretch out, and I can have guests come. I have room, I have a king-size sheet. For my friends I say, “No, sit down. I got room.” I’ve always been like this. I know so many people on the beach. They call me The Mayor at Riis Beach.

Gilian: And where on the beach do you usually sit?

Ralph: It’s the end of the beach where most of the gays sit. Mixed people sit, which I call “the Village.” Years ago, they used to be numbered back then. That was bay one. Back in the late ’60s. That was mostly African Americans, Latinos, and a few whites. Through the years it started changing, different people started coming to that area. And you had a mixed group of people who would start coming here. But it has always been nice, no fights.

Gilian: Tell me about the younger Ralph. Did you ever feel threatened in any way when you first started going to Riis?

Ralph: You know, when I started to experience tension— or even have any conflict that was highlighted— it was mostly when the beach was nude. It was nude twice over the years. The first time it was nude was the mid ’60s. One girl I knew saw a guy had a camera hidden inside of a boombox. She went up to him. She pulled out a knife, she’s like, “Give me that film.” Everybody was watching. He got nervous and he opened up the boombox and the camera was in there. He had to pull out the film. She took the film and she stretched it out. And everybody started clapping! But now, most people are half nude anyway. You know, g-strings, the girls are topless. Nobody’s bothering anybody. For me, it comes down to fun.

Gilian: How does it feel for you now to be there? We’re going through this pandemic, and more disconnected in a way from each other. How does the community at Riis feel now – compared with how it felt then in the ’60s?

Ralph: Well comparing the beach now with the way it used to be back then, ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s: it was a more “up” feeling, and more fun. The different outfits, people would just come out with robes on. And different girls who had different fabulous bikinis that you would see in Bergdorf Goodman or Saks Fifth Avenue. Stuff like that. Some models used to come out there back then. You would catch a famous model sitting in the area. It was just more fun back then. The atmosphere was more fun.

Gilian: More playful?

Ralph: Yeah. And on the boardwalk area there were more places where you could eat restaurant seafood. Game rooms. It was just more fun back then. Things to do. And you didn’t feel threatened with all of it, you could go to the boardwalk, nobody would bother me. Things like that. Today, now you have a younger crowd coming in the Village area. The new kids are now there. They’re nice, they’re really nice. They’re in their own little groups. It’s just different. But it’s still very nice. Now we are getting a lot of people from Manhattan coming here now. A lot of the people from Staten Island are coming in here now, because now they have ferry boats that come from Manhattan, Lower Manhattan. The crowd at Riis, you don’t see at Fire Island or Coney Island. With the kind of clothes and dresses… it’s just more fun at Riis.

I just recently had a girl tell me that the big building… I call it The Big House, it’s a big brick building on the boardwalk.(2) They’re going to make it a hotel.

Gilian: Oh yea. I heard that too. What do you think of that?

Ralph: Personally, I think it could make the beach look nicer. Hopefully it could bring Riis back to where it should be: more glamorous, more fun, fix up the roads [and] the boardwalk. I don’t think it will necessarily make us move the Village area. How could they do that? Well, it’s public, but it’s a federal beach. They have their own rules.

Gilian: That’s an interesting perspective. Some organizers I know believe it could displace the Village area.

Ralph: I don’t think so.

Gilian: Would you like to get back to the parties? What made the shows feel so different than what you would see in an average fashion show?

Ralph: People would ask me, they would [say they’d] like to help me with things. I said, “No, I didn’t need the help. I know what to do in my mind.” They didn’t realize, where I come from— my background in design, fashion, and stuff like that— that I knew how to do all this by myself. I know exactly how… I know how I want the tents; what direction I want the speakers to angle the water, so the sound goes over the water— not down the beach to bother anybody, things like that; where to put my tables for the food. I want the poles lined up around the host area, so everybody will be inside the ten foot poles, because everybody will sit along the runway. My designers would design outfits you believe you had never seen before. Things like something Grace Jones would come out with, stuff like that.

Gilian: How about the participatory aspect of the shows?

Ralph: I would snatch people out of the crowd. If the design needed another model, I would go out of the tent and I’d say, I need a girl size 10, or whatever size, and I would just grab any person in the crowd that’d like to come in, because the fashion show was for anybody who wanted to be in it. I mean my friends who wanted to be models, I’d tell them, Go in the tent, put on the clothes and walk the runway! So it involved people in the crowd also to make them more part of it. And then, they had more fun.”(3)

Gilian: Were there other parties like that going on at Riis, besides yours?

Ralph: While I was having mine, another group of black guys who called themselves The Black Pride started to have a dance party out there. Their party was three weeks before mine. There were four or five of them, and they put a little money together. They had big tents, a dance floor, and a performance later. They had more connections than I did. The main thing, after their party was finished, they would leave garbage and trash– dirty– all over the beach. A real mess. The beach people hired a cleanup crew to clean up their mess, and they tried to present the bill to them. I heard that The Black Pride guys said, “We’re not going to pay that.” So the beach people said, “Oh, you’re not going to pay for it!? Okay, no more parties for nobody on the beach anymore.” So that one messed me up. That’s why my parties stopped. That’s why I couldn’t have mine. And I had nothing to do with them. I didn’t even know them, these people. So since then, up to now, that’s why I haven’t had my parties. Maybe now, I probably could get a permit.

Gilian: Did it matter that your fashion shows happened around so much nature, close to the ocean, with the sun coming through, and all the dunes there? I’m thinking about the waves of the Atlantic Ocean, the rose bushes, dolphins swimming…

Ralph: Having this kind of fashion show on the beach made it a little more exotic. The audience felt relaxed in the hot sun; being basically half naked, with no clothes on, watching the show. Seeing the people come with beautiful colors— in all red against the white sand, or all blue. The outfits everybody would come in. All because I would say the color for that year. I said, Let’s have a neon party. Could you imagine the neon colors that came on that beach? Over 200 people in neon colors, and overhead, neon fabric comes from ten foot poles. That was the most pretty, out of all the parties.

Gilian: Did you ever feel like the stories you wanted to tell through the parties were about the ocean, or about the dunes, or the dolphins that are sometimes out there?

Ralph: Occasionally we saw dolphins out there, which is very surprising. I think the first time I started seeing dolphins out there was the early ’70s. We saw them jumping, we couldn’t believe it in this water. Everything was just so beautiful at the time. Even now, it still has this magic to it.

Gilian: Did you know that jumping is sometimes a way they communicate with a mate or another pod?

Ralph: Jumping has this magic to it, it’s beautiful!

Gilian: They’re pushing off the water and meeting the air on all sides! It’s so open and light, and also so present. Communities want to fly, windmilling around, and also want to feel at home. Right here, but also free completely.

Ralph: Even now a lot of people still don’t know where Riis Beach is. In Manhattan, they ask, “What beach do you go to?” I say, “Riis.” They say “So where is that?” I’m not surprised that people still don’t know. It is kind of nice, because it kind of makes it a more private beach for us. I’ve been a beach person all my life. Riis Beach, from day one, I loved it right away… I used to go every weekend by train or by bus. It was just, you felt more at ease at Riis. It fits my personality, I would say. It’s more fun.

Footnotes:

(1) That day, he was wearing a beautiful black fleece and an onyx necklace from Brazil.

(2) The abandoned Neponsit Beach Hospital, known as the Neponsit Children’s Hospital. It once served as a tuberculosis sanatorium and operated from 1915 to 1955. Neponsit Beach Hospital mostly treated children, but by World War II, began to also treat military veterans until the hospital’s closure. The hospital was later converted into a Home for the Aged, a city-run nursing home that closed in 1998.

(3) I was reminded of Vogue’s article “2016 Was the Year Real People Took Over the Runways”, which cited luminaries like Hood By Air, Eckhaus Latta, and Chromat as pioneering this tactic of placing real people on runways.

Gilian Rappaport (she/they) is a transdisciplinary artist, writer, and herbalist based in Rockaway Beach, Queens. She was born and raised in New York between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. A descendant of Russian and Polish migrants, she is a gatherer, and seeks to engage the intersections of nature, play, stories, and sensory experience to explore queer possibilities. She is also known for her design and research work, supporting the vision for regenerative projects that are renewing, restoring, and nurturing our world. For updates on upcoming projects, sign up for her newsletter and follow @gilnotjill.

Ralph Hopkins (he/him) is a 73 year old native New Yorker residing in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn. Known as The Mayor at Riis Beach, he threw participatory beach parties there in the ‘90s involving fashion shows, DJs, and food, and has been a consistent presence for the past six decades. He is also a former chef, and in the ‘70s, became a five-time gold medalist — and one bronze — at the Madison Square Garden Harvest Moon Ball for the Lindy Hop and Jitterbug. He is also a US army veteran. To get in touch, contact Ralph on Facebook.

Uncomfortable Conversations: Money

“It’s related to being able to be more present and less controlling. Which also relates to controlling money, being constipated, having a tight clenched jaw. So many things with white supremacy. So to me, there’s a connection between shitting and money.”

CAROLINE WOOLARD

In the last five years we have found ourselves in a cultural moment of reckoning, in which survivors are being listened to and supported and perpetrators are being held accountable more than before. However, what emerged is also a culture in which any infraction results in the call-out and cancellation of the individual in question. I believe that this kind of tipping of the scales in the opposite direction serves as an usher of transformation, but that it is not a sustainable or regenerative space to remain in. To create a culture that embodies values of cooperation, pluralism, and collective and democratic stewardship (like a Solidarity Economy(1)), we must be able to acknowledge the histories and experiences we come from in a generative way. And yet, we find ourselves in this moment where people are afraid to learn because the fear of getting it “wrong” is more powerful than the fear of their own ignorance.

Informed by my experiences as a biracial Mexican American woman, bodyworker/somatic educator, dancer, and cultural organizer working within the Solidarity Economy, I am observing a need to cultivate the skills to navigate conversations around topics and realities like race, white supremacy, gender, money, and any and all subjects that surface discomfort. I am engaged in an effort to use my personal forms of knowledge as strategies to help develop this as a cultural practice. It is a series of intimate meetings I’m calling, Uncomfortable Conversations.

Uncomfortable Conversations explores discomfort as a place of discourse and connection. Both verbal and non-verbal dialogue serves as the medium that traces back pathways to locate the roots and home of discomfort that reside within us as individuals, and form our social and cultural sinew. And then there are the bodies— our bodies— that have navigated these systems of oppression and have both delivered and endured violence across generations. Bodies that are doing the work of abolition and liberation. How do we bring them into all that we do in a way that acknowledges their labor, and understands them as places of discourse?

In Uncomfortable Conversations, we are invited to observe what our bodies are telling us. In this conversation, artist and cultural organizer, Caroline Woolard, who I met through our work together for Art.Coop’s Study-into-Action(2), beautifully mapped her somatic responses (see diagram below) as memories surfaced. Her sensations served as a dialogical partner as we explored the stories and lineage around the word ‘money.’

Uncomfortable Conversations places equal value on the topics and words we discuss, the somatic responses that emerge, and the skills that we cultivate to navigate discomfort with curiosity and resiliency. It is my hope that as these conversations continue to happen, that instead of the isolation that is felt from exiling discomfort from our ‘selves’ and society, we can embrace and understand that discomfort as a place of shared belonging.

Caroline is an artist, organizer, and thinker whose work offers a reframing around economies and exchange that is collaborative and disrupts the status quo of who defines ‘economy’ and how we participate in economic exchange. I want to acknowledge and honor the trust that Caroline placed in me by agreeing to have this conversation together and share it with each of you.

*Caroline and I have never met in person as she is currently in Berlin, Germany and I am in Northern California, U.S. Our conversation was conducted over zoom.

Marina Lopez, Cartography of Discomfort (Caroline and Marina), 2021

Drawing from moments and sensations in our conversation, these images begin the process of mapping the somatics of our dialogical exploration around money. The images function as a way to create a visible bridge between the intellectual experiences and how those surface in our bodies.

Marina Lopez: So I’ll share with you some of the guiding questions because they’ve been helping me ground a little bit in this work:

How can we learn to become better stewards of vulnerability?

When, in the history of humankind, did emotional vulnerability begin to register in our brains as a threat and therefore our bodies?

What does it feel like to listen/hear, and to guide/follow with curiosity?

Caroline Woolard: Yeah. Cool.

Marina: Do you have any questions or comments?

Caroline: Yeah. Thank you! It’s so beautiful to hear this other side of you. It’s vulnerable for both of us to be and share this creative side and practice. So that’s nice. Yeah, it’s really exciting!

Marina: Yeah, thank you [giggles]. It feels special and sweet to share this first conversation in the project with you.

Caroline: I’m excited. So tell me, where do we go? [Both laugh]

Marina: So I’d love to start with this experience we had while we were co-organizing Art.Coop’s Study-into-Action. We were wrapping the seven-week series and making sure all of the artists and facilitators had been paid or knew how to submit an invoice. One of the artists invoiced for a lot higher than what we had thought we were paying them. We went back into our correspondence to check in about what the agreement had been. You, me, and Nati had this exchange internally about how to proceed because the invoiced amount was actually higher than what we had agreed to. I thought it was interesting how we all had different inclinations for how to handle the experience. What stuck out to me about it was that you had said something like, I don’t like having conversations around money. Or, I don’t want to have that conversation. So I became really curious about that. One, because I’m still getting to know you as a person so it was interesting for me to learn that about you. And also I found it interesting because your work has been so much about exchange and economics. And then Study-into-Action specifically was bringing together this money world and creative world so I was really like, Huh, I want to explore that a little more with you. Like, what’s that about? So do you want to share anything about that experience?

Caroline: Yeah. The part I’m remembering is that the artist thought she was getting paid $500 per session and we had thought it was $500 for the whole thing, four sessions. We thought it was $100 a session rather than $500 a session, so it was so much less. So maybe what I meant to say is, I’m uncomfortable talking about money and paying people less. And the convo around, we actually want to pay you $500 rather than $2000— it’s that gap that makes me so uncomfortable: it’s the conversation around someone’s value with dollars. That’s the part that triggers so much rage and a sense of being controlled. Speaking of the body, this somatic feeling, like a tightness; feeling like I’m trapped. The way exploitation feels. I feel like it’s deep in my eye sockets. A feeling of hot tears welling up. [Hands are scrunched together beneath eyes] Or in my throat or in my chest. A tightness. [Hands in loose fists at center of sternum]. It just feels SO wrong that people can’t have what they need in order to survive. And so a lot of the work that I’ve done is not about money, it’s like, how do we not use money, even though of course we have to. So it’s about, how do we engage in exchange or barter or mutual aid or gift giving, or share our resources abundantly. Like I have a place in Berlin where people can come and stay here. I can help with this, I can help with that. But when it comes down to, maybe she [the artist] thought that she was going to pay rent with that, I just go into fear. Total fear. Like what you were saying about, when did vulnerability make us as a human species feel that we were being threatened and go into a space of fear, or fight or flight?

Marina: Yeah.

Caroline: Yeah, it feels like that. I guess there’s also this feeling about feeling let down around it [money] in particular. Like expecting something and not receiving it and having a sense of unclarity. And yeah it just brings up a whole family history going back for so long, where you thought you were going to have whatever. Like my grandfather thought he was going to have a job on this tobacco farm but he didn’t get it. That’s why he tried to rob a bank. That’s why he failed and changed his last name. And why my dad was born with a fake last name and didn’t know that he had family. And then came back to the farm when he was 10 and was raised in this very abusive family. And then my dad fled, and managed to go to college and make money, randomly, which is a long story, which we could get into. But he wanted to be a philosopher. He was drafted into Vietnam, all these things happened. He eventually became a doctor and actually made money and then raised me in this world that he didn’t feel comfortable in.

But then also my parents got divorced when I was 18, and they were so emotionally devastated with each other that they basically abandoned me. So then when I was in college, I had an expectation that I would be taken care of, like also financially, because I was raised totally owning class. [I] had money growing up from my dad and he wanted me to be comfortable in this world of owning class people. He put me in private school and was like, you’re gonna learn this world that I didn’t learn. But then when I was 18— he supported me a little bit and also I went to Cooper Union, which was free— but then once I was 22, he was like, No you’re done, which I had not expected at all. And emotionally he was also like, I can’t even think about you, because I’m so depressed. And so it brings up all this feeling of expectation and love and care. Like I just feel it in my throat [brings hands to throat]. It’s like [snaps fingers quickly across face] and then the rug gets ripped out from you. And so [these kinds of conversations about money as it relates to someone’s value] has this feeling that triggers all of that in me.

And I think that’s generational too. Like, Oh, you thought you’d have a family and a farm and help your mom on the farm. But no. And then my dad was, I don’t know what he thought. I think he just wanted to get out from the youngest age, and that sentiment echoed from his dad.

And then for me, I thought everything was amazing. I’m just living this fancy life. Everything’s going to be easy. And I kind of knew it was a fancy life ‘cause my dad had always told me how he hadn’t had running water. And reminded me that, You’ve got this fancy thing, or, I’m going to give you everything.