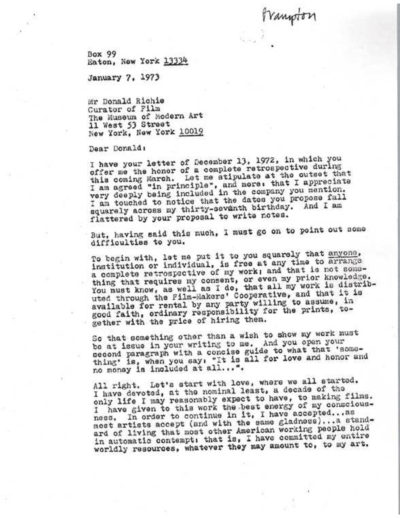

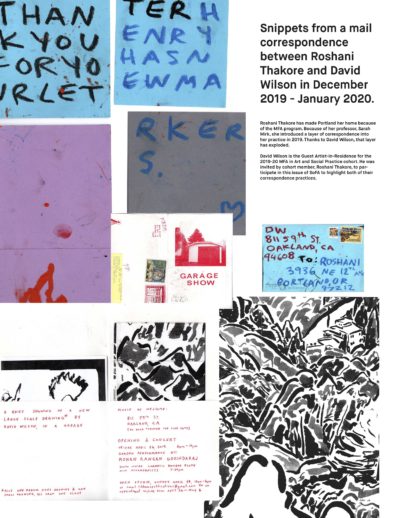

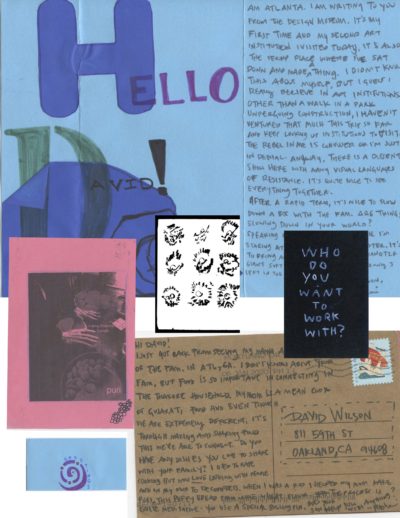

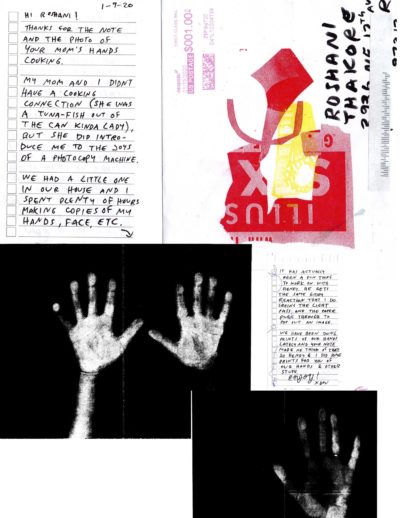

Issue 4: Exchange

An Interview with Cassie Thornton

Cassie Thornton Wants to Heal the Economy

Last October, Cassie Thornton popped up a tent in a downtown Oakland plaza offering “Luxury Real Estate Facials.” This was one of a series of collaborative projects under the title Desperate Holdings Real Estate and Land Mind Spa, using clay gathered from the construction pit underlying San Francisco’s newest and tallest skyscraper, the Salesforce Tower. While her invitations to real estate agents went unanswered, other workers on lunch break and passers-by stopped, talked, lay down, and received facials. They often fell asleep while Cassie read to them from a pamphlet poetically deconstructing the metaphorical and all-too-concrete dynamics of real estate speculation, hyper-inequality, liquidity/illiquidity, insecurity/securitization, and the resulting distortions in the mind, body and spirit of people living under predatory capitalism.

Flash back to another project in fall 2017: a group of men lay on their backs on the floor of a London black box theater with balloons stuffed up their shirts, breathing heavily in time with each other. Cassie Thornton and a crew of female friends strode around in dark balaclavas, spraying them with water. “This is what generosity looks like!” they yell. “We’re doing this because we care about you.” This was a labor ceremony, a birth rite for a new feminist cryptocurrency.

Both of these projects are perfectly logical extensions of Thornton’s career as the director of the Feminist Economics Department (FED).

Thornton’s experiments with debt, exchange, and radical imagination are anchored by her own family experience of having lost a house to predatory lending during the subprime mortgage crisis, a decade teaching in NY public schools, as well as being displaced by gentrification in the Bay Area. I first heard her name in connection with Strike Debt, an offshoot of Occupy Wall Street. Strike Debt organizers started a project called Rolling Jubilee, raising funds to buy up uncollected debt on the secondary market for pennies on the dollar. Then, they notified debtors that their debt was absolved. To date, Rolling Jubilee has abolished almost 32 million dollars in debt.

Thornton graduated from the California College of Art’s graduate Social Practice program in 2012 and currently lives in Thunder Bay, Ontario, also known as the racism and murder capital of Canada. With her partner, Max Haiven, she runs a little institute at Lakehead University called the ReImagining Value Action Lab, or RiVAL. They also co-founded University of the Phoenix, which teaches “courses for the dead that the living can attend,” and is currently developing a series of radical “financial literacy classes”. Under the FED moniker, Thornton’s work includes performance, hypnosis, yoga, visualizations, revenge consulting, do-it-yourself credit reports, interactive gallery installations, a children’s book and grassroots organizing.

The following segments are remixed from two different interviews with Cassie, in October 2018 and December 2019.

—Zeph Fishlyn

Complicating Care

My work has two sides. First, there’s a direct line of care. And then the other part of it is quite vengeful—about burying some radical politics within a service like yoga or a facial or a workshop or whatever.

I didn’t really realize that my work was absurd until recently. I’m from a situationist tradition, from a lineage of performance artists and magicians, but I always thought that all of my projects were really straight. I really thought that I was a person who was going to get a TED Talk, be on Oprah. I made a series of online yoga videos about confronting authoritarianism, confronting our addictions to cell phones and social media, and going beyond financialization to another world. The goal of making the videos and doing live performances was to figure out how to be a good enough yoga teacher to go into corporate yoga studios and deliver a kind of radical politics that nobody knew they wanted. I thought that wearing all black and making these very dark yoga videos was going to be super commercially successful! But I wasn’t very good at hiding that this project holds at its centre some aggression. It reveals how yoga is a weapon used by capitalism on us, and questions what it would mean to heal from that.

Most of what I offer is stuff that people don’t want. Or they don’t know they want it. And so they are not going to pay for it. Maybe eventually they would come back for it. But at that point, I don’t really want to give it to them anymore.

A couple of years ago in Miami, I had a residency and I asked to meet with the board of directors of my hosting organization, who are all pretty high level finance workers and corporate lawyers. I did interviews with them about their history of borrowing and lending and then I had them do a hypnosis project where they imagine debt as an image or place. For them, debt is mostly a commodity. We talked about it, we visualized it. A lot happened in the process where people confessed to me about really bad things they had been involved in, and how they felt trapped within the financial system that they were also on top of. This work helps me understand that everyone is suffering and everyone wants a transformation but nobody knows how to do that, because it would mean completely changing their lives, and no one can imagine how to do that alone.

Everyone’s suffering right now. There’s a lot of fingers being pointed sideways, and not enough fingers being pointed directly up to the things that are actually smashing us. Specifically on the left. We need to support each other to punch up. One of my projects is revenge consulting. It’s my job to remind people what the root problems are, problems that are ruining the planet and ruining our ability to actually live together at all. Tech giants are a great example. I think we have to figure out our collective targets. Our targets can’t be each other. Many of our common targets have names, addresses, and wives, and we can confront the powerful. That’s my game. For me, revenge is most beautiful when it’s collective and it’s about bringing down something that is collectively oppressing us. Revenge against an economic system, revenge against forms of power and control that are actually dominating our whole experience. And I am not opposed to vandalism either:)

University of the Phoenix and the Radical Financial Literacy Tour

I started a project called University of the Phoenix with my partner, Max. We stole the name and image of the University of Phoenix, which is the biggest, most predatory for-profit school in the US. University of the Phoenix really takes advantage of suburban and rural people of color and poor or working class first generation college students. They get a horrible education and spend the rest of their lives paying off a debt for a university degree that actually hurts their ability to get a job. We are like their ghost institution, haunting them and stealing all their nice graphic design.

We teach “courses for the dead that the living can attend.” For me, thinking about the dead helps me understand that what I’m working on right now might be the work that someone else started, and someone else may finish my work after I am done. It takes the pressure off, because we’re connected to so much and to so many people whom we can’t see and who we don’t understand. Bringing death and the dead into the room changes the idea of where we are and what we value. It opens up time and a sense of who we are outside of being financialized subjects (for example, the dead don’t worry about rent). With the University of the Phoenix, we occasionally do séances. We brought Ursula Le Guin into the room and we brought Hannah Arendt right after Trump was elected. Within these big anti-capitalist rituals, we’re trying to create transformative situations where we all confront the unknown, and it’s funny but it’s not a joke. We work hard to create paranormal situations where the world as we know it doesn’t seem so closed because we are connected to more than we can see, and a lot more is possible than just continuing to live and work and eat and sleep and consume.

As University of the Phoenix, we also teach a radical financial literacy workshop to help people who feel really mired in debt or other impossible economic conditions. In these workshops for anyone, we specifically focus on the idea that financial survival is not actually an individual responsibility. It’s impossible to survive or flourish in this economy, and that’s a collective, political, and a social problem. And the only way that we’re going to fix things so that more people can thrive is to actually change the economic system. In the workshops we show people how the economic system works, what is it doing to them and to everyone they know, and what it would take to actually confront it as a collective problem and not as a personal issue.

Every institution has so much funding for financial literacy. If you say “financial literacy,” it’s like a secret passcode, and suddenly a door appears where there was once a wall, and there’s a thousand dollars behind it. All over the world, people have decided that everyone needs financial literacy, which could really be called ‘capitalist obedience’, and there has been so much money thrown at it. Then we show up, and we say, actually financial literacy means understanding you’re a part of society, and your financial problems are linked to the financial problems of every other person you know, and to a government and to a set of corporations that are not making it very easy to live. We did a group of workshops last year in Thunder Bay where we got our footing and figured out how to teach the course, and then we just recently went to Minneapolis and did it in a bunch of libraries. Now I think we understand more about how to make it actually work for people so they don’t just leave happy, but with a set of skills and a project that would help them feel like there’s some practical steps to take towards a better situation.

One thing I love about teaching these kinds of workshops is that we get to do a lot of show and tell about different social movements around the world that succeeded when people got together and decided to work on each others’ behalf or stand up against different forms of austerity. It’s amazing to show people who have never been exposed to social movements a little bit of what has been happening. Showing little clips of documentaries where working class folks can see people who look like them having a really good time while seeking justice on behalf of themselves and others. That’s the mystical thing, that’s the missing link for people, because so many North American workers never thought of themselves as potentially more than workers. Many have never thought of socializing in these other ways, and they’ve definitely never thought about how fun working on collective liberation could be. That’s basically the secret weapon that comes at the end. People get super hyped to understand how much is possible and how much is always happening under the surface. The hard part is what you do with all that excitement. We’re always looking for new groups we can partner with so there’s something to sign up for, for our workshop participants. We need somebody who’s going to contact them and bring them into a social movement where there’s now somewhere to practice. We always refer people to the Debt Collective, which came out of Strike Debt—a giant debtor’s union.

Money and exchange within project funding

Some of my current projects can get funded because they do somehow “register” within the art world, and I’m trying to organize how I redistribute that funding. For instance, now that I live in Canada, I sometimes work with wealthier institutions like the Canada Council for the Arts, or Ontario Arts Council. So how can I take that money and sustain myself and also sustain my other [unfunded] collaborators and projects where I need to foot the bill and pay the workers? I need and want to support people who are not working within the art world, who don’t have money, or who are unfundable because their work is anti-capitalist, so they can afford to spend time doing radical post-work with me.

I have to constantly remember that the way that I’m valued in different situations looks different. Sometimes I’m able to actually receive money as a form of value, and then there are a lot of times when I’m not. And I would usually much rather work in the situations where I’m not able to get funding—where I’m doing something too weird, or I’m doing something that is in service of something that has such radical implications or demands that there’s no possible way it’s going to get funded. That might mean that I’m using funds from another project to pay someone to help me.

I started to try to think through a way that I could receive a sense of exchange from nonprofit galleries when I work with them. A lot of times you do a project at a small gallery, and maybe it’s the most awesome gallery and so many cool things are possible there. Maybe it’s cooperatively run, anti-capitalist, or an activist space. Those places, especially in the United States, never have money, but that’s where the most stuff is possible. So, what could I ask for? I don’t only want money, because we’re trying to build a new world with new values now, and the gallery can’t afford to pay me anyway. So instead it’s become my policy to ask the gallery for a favor. And my proposal is for the people surrounding the art space to try something socially-experimental with me; for example, to take phone calls with me, to set up a workshop, or to introduce me to five of their board members.

Recently I started to do this experimental form of health records keeping—a viral, anti-capitalist health project. And I thought, if places can’t pay me, maybe they would help me experiment on this project. I move around so much to do projects, and I’m pretty new to Thunder Bay where I live. I don’t have a big community of people to try ideas and projects out on yet. And so what I really needed was people that would be willing to try this health project with me. Maybe they’ll let me have a workshop with their workers. Or maybe they would let me work with three other people for a three month experiment. That could be happening underneath the project that is public facing, or before or after the project comes together.

If you’re responsibly asking for a favor you think is within somebody else’s capacity, it could be much better for them than paying you money. It opens up a conversation about value, and allows you both to discuss time and energy. If you already have the means to survive, maybe there are ways to honor your time and work without more money exchange. Just because we’re used to using money as a way to show that we appreciate something, doesn’t mean it is the only way. Money is not the highest form of flattery!

The Value of Poetic Labor in an Activist Context

Zeph:

What about doing work in a context where the artist is the initiator, seeking collaboration with people who have not asked for it? Before I came to grad school, a lot of my public work was very practical, very service-oriented, especially when working with activists. I’d be like, tell me what you need—I’ll get the cardboard. I’ll produce the visuals for you, I’ll host the space and build your props. I’ve been very cautious about asserting my own voice as an artist in those collaborations. But it becomes an unequal exchange and I burn out.

For instance, I have a longstanding involvement in housing activism in the SF Bay Area. Here in Portland, I’ve been trying to make work related to housing with a more open-ended approach that includes more emotional and poetic elements. It feels clunky—I’m asking myself, what am I offering people when they step closer to the table or take my phone call or meet with me? How do I work with people who are super busy dealing with really concrete conditions around housing and policy and I’m offering them something poetic?

Cassie:

I totally understand what you’re saying. The one really poisonous thing (I got many good things too) that I got out of grad school was feeling like a burden when entering a space where they’re doing “real work.” Say you want to work with the labor union. All these organizers are working their asses off and you’re like, “I want you to do this project!” The goal is to get to a point where you know that by being there, you are offering something really valuable, and that they will want to eventually have an exchange with you—because you are an expert in what you do, you’ve done this so many times, and your labor is valuable. The kind of work that you do, Zeph, does have value. You really support people to transform their ideas, situations, and themselves by showing that something more than they realized is possible. Exchange is pretty important, because otherwise you’re in a generosity mode, or a white benevolence mode. You’re classing yourself if there isn’t exchange in some way.

All of my projects feel much better to me when I’m part of social movements at the same time. That allows me to really think strategically and collectively, what does it mean to heal? What does it mean to create change or help somebody? I need to be grounded in a sense that I’m actually doing something before I can fuck around doing the more abstract, symbolic or aggressive work around healing or economics.

In Thunder Bay, I get a lot of energy from participating in a group called Wiindo Debwe Mosewin (formerly called the Bear Clan of Thunder Bay) which is a feminist indigenous-run project that means ‘Walks in Truth’. We do an alternative street patrol and make sure people on the street are ok. At RiVAL, we do lots to try to help people figure out how to organize or start anti-racist social movements. There are a lot of people here trying. Positive change is possible, but maintaining the imagination of what we actually want, besides what we’re actually being offered, is pretty hard sometimes. Being in touch with other artists and keeping up with what other social movements are doing really helps keep my radical imagination alive.

Cassie Thornton is an artist and activist who makes a “safe space” for the unknown, for disobedience and for unanticipated collectivity. She uses social practices including institutional critique, insurgent architecture, and “healing modalities” like hypnosis and yoga to find soft spots in the hard surfaces of capitalist life. Cassie has invented a grassroots alternative credit reporting service for the survivors of gentrification, has hypnotized hedge fund managers, has finger-painted with the grime found inside banks, has donated cursed paintings to profiteering bankers, and has taught feminist economics to yogis (and vice versa). She has worked in close collaboration with freelance curators and producers including Taraneh Fazeli, Magdalena Jadwiga Härtelova, Dani Admiss, Amanda Nudelman, Misha Rabinovich, Caitlin Foley and Laurel Ptak. Her projects, invited and uninvited, have appeared at (or in collaboration with) Transmediale Festival for Media Arts, San Francisco MoMA, West Den Haag, Moneylab, Swissnex San Francisco, Pro Arts Gallery & Commons, Dream Farm Commons, Furtherfield, Gallery 400, Strike Debt Bay Area, Red Bull Detroit, Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts, Flux Factory, Bemis Center for the Arts, Berliner Gazette and more.

Zeph Fishlyn (pronouns they/them) is a multidisciplinary visual artist dedicated to personal and collective storytelling as nonlinear tools for reinventing our world. Zeph’s participatory projects, drawings, objects and installations nurture alternative narratives by questioning, dreaming, distorting, celebrating and demanding. Their most recent work explores absurdity, embodiment, intimacy and playfulness as sources of resilience and creative subterfuge. Zeph is also a serial collaborator with grassroots groups focused on social and economic justice and LGBTQ liberation. Zeph is an MFA Candidate in the Art and Social Practice program of Portland State University.

Medicine Exchange

By Zeph Fishlyn

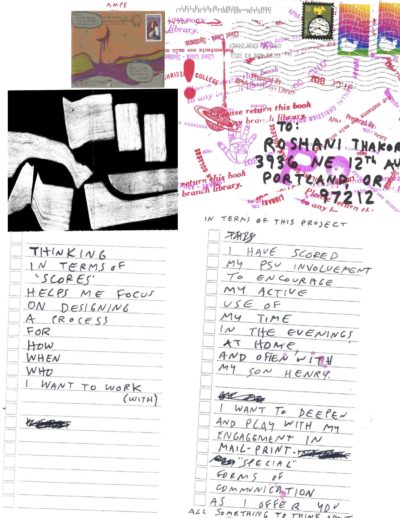

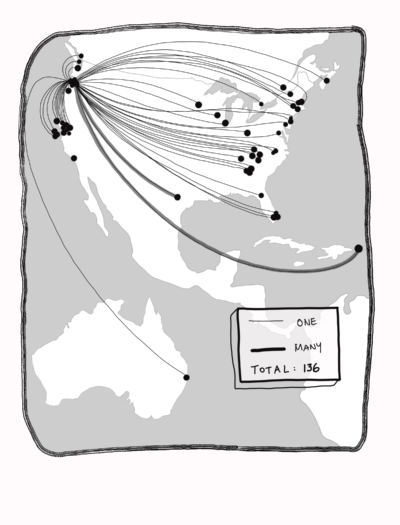

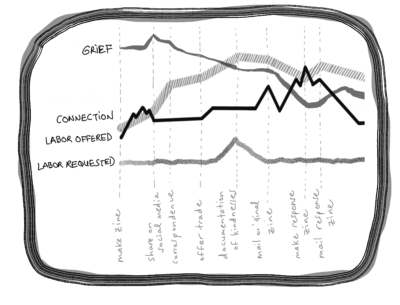

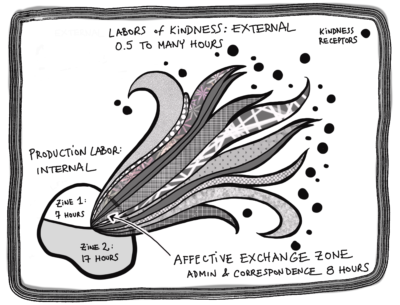

Medicine Exchange started as a simple, tiny one-page zine project: I wanted to share a few different ways I was coping with grief stemming from a series of difficult events in my personal life. When I posted it on social media, I had a sudden flood of requests from friends and friends-of-friends-of-friends for printed copies. They wanted them for themselves, they wanted them to gift to friends of theirs who were going through hard times. One person in Puerto Rico wanted a bunch to share with his community of queer and trans people struggling in the wake of Hurricane Maria. Another in Atlanta wanted to pass it around as part of her organizing work.

It felt strange to ask for money in return for such an intimate work. Also, one of the strategies I had illustrated in my zine was “offer care to others.” So I announced that I would mail a copy of the zine for free to anyone who sent me some kind of documentation of some small act of kindness they were sharing in their own life. I compiled all those responses into a new zine, which I sent back as a pair to the original one for everyone who had contributed a kindness.

I imagined this project as a sort of ripple effect, moving outwards. I underestimated how much the correspondence, the sweetness of peoples’ actions and sharings, the sheer exchange of affective labor and intimacy would ripple back and cheer me up. While I did not ask for much labor in return for all the work—just an anecdote or a text message or a photo—I got a glimpse into the work that so many do on a daily basis to try to make the world a little easier for others.

Hayden Island RV Park Exchange Subculture: A Personal Reflection

By Shelbie Loomis

Jantzen Beach RV Park, by unknown, © 2009-2018 Jantzen Beach RV Park

We live on an island where our nomadic people exist. We live in an RV Park that cultivates exchange so we can thrive.

When my partner (Charles) and I moved onto Hayden Island, we first met our neighbors when they came outside to watch as we backed up our forty-foot, twelve-thousand-pound payload into a narrow hook-up spot which would be our home for the foreseeable future. After a few tries, and feeling the pressure of being watched, I could feel myself become irritated with being such a spectacle. “I see you have a dog with you. What type of dog is he? He looks like a pit bull.” The woman called out as I performed my practiced landing signals to my partner. I could tell Charles was getting agitated with my neglect, and as I was standing there implementing my last task for the day, I was too. I gave her a short answer and turned my attention back to the task at hand. “I can tell you don’t want to talk right now,” she retorted and quickly went back inside to give us some space. Later on, I mentally kicked myself for being so short. After all, I knew the protocol for new arrivals and knew how important it was to have open communication with your neighbors. The RV (Relaxing Vacation) community was a complicated fabric of individuals who are reliant on each other to survive, to grow, and thrive through open exchange and alliance. And I knew that if I wanted my family to be supported in a time of need, it was necessary to be hospitable.

Fig. 1: (left) Dogs in Cougar RV, 2019. Photograph: Shelbie Loomis. Fig. 2: (right) With Ulay in the Citroën van, 1977-1978. Photograph: courtesy of Marina Abramović Archives © Marina Abramović and Ulay. DACS 2016

Before venturing out of the Southwestern desert to travel across the United States to the Pacific Northwest, I had done my share of research about the lifestyle of living in an RV full time and possible boondocking. I watched the videos, read articles, fantasized about the whimsical tiny house living that came with intriguing people that traveled a lot. I thought about Marina Abramović and Ulay who lived in their Citroën police van from the late 1970s into the 1980s and according to the Guggenheim had cultivated a “lifestyle choice that merged with their belief that freeing the mind and spirit was only possible after physical deprivation”. To me, I felt that this lifestyle could provide me a solution away from consumerism and capitalism while I focused on what freed my mind and spirit.

When asking for advice from people that were apart of this community, I realized that the most important information to know were all things that came with word of mouth. Things like “when should I empty my black-water tanks out?” or “which navigation routes should I take that don’t have the steepest slope highways?” It became apparent that if you were going to get on the road and successfully navigate through the country as a nomadic citizen with no special training, you had better learn how to ask for help from the people that knew best.

Fig 3. (left) Letters from Lyn. 2019. Ink on Paper. 8.5 x 11” Fig 4. (right) Mieko Shiomi. Event for the Midday (In the Sunlight). 1963. Event Score. Ink on paper, 4 9/16 x 7″ (11.5 x 17.8 cm)

The chance to exchange information, trade knowledge, use of specialized tools, or learning how to work on “rigs” began to re-contextualize simple actions, ideas and objects from everyday life on the road into a form of performance. A performance that came with a collaborative audience, should one be open to the folks that abide by the law of hospitality. I became interested in people, their stories, and their performances, asking them to exchange techniques through different forms of communication. Some of the correspondence resembled event scores, instructional by nature, which made me think of works such as Event for the Midday. (See Fig 3 & 4) When asked to take something that felt intuitive and place it down on paper, most people took the time to act out the action and close their eyes to picture the event as if it were happening in front of them. Shut eyes. Open eyes. Shut eyes. Turn the wheel.

Fig 5. (left) Robert with RV. 2019. Photograph by Shelbie Loomis. Fig 6. (right) Neighbors with RV. 2019. Photograph by Shelbie Loomis.

However, tThrough my inquiry and deeper conversations with people I asked questionsinto questions such as why they felt the need to have such an open forum of communication, shared resources and knowledge?; Tthe reactions and explanations were full of economic downfall, personal and family illness, and a series of unfortunate events that lead them to be placed in these circumstances. Conversations lead to comparisons to the lives they used to live and aspirations to once enter back into a larger sustainable house. Mostly, everyone who lived in the park was no longer considereding themselves as “passing through” and were on their charted paths to better their futures or upkeep the ones they already had; like for Robert (left) who owned an RV towing business but had outgrown his RV since the birth of his daughter and looked forward to the day that he did not have to spend the time or money maintaining it, or my neighbors (right) who preferred not to be named, who described a life of traveling and chasing rodeos around the country before the crash of 2008 which landed them in the RV park for twelve years and on their second RV.

As a community, we knew each other’s stories and if the rare opportunity arose where a long-term resident parked alongside your dwelling place; there exists a vested interest in knowing what kind of strengths or weaknesses you could bring to the mixing pot. Could you be trusted to watch your neighbor’s RV while they are at work? Would you participate in donating your cans for the woman down the street who is disabled and needs the income? Are you available to help a widow reattach her water-hose since her husband is no longer alive to maintain the rig? The day Charles and I pulled into our lot, we were being assessed to see if we should be welcomed or ignored.

Fig 7. (above) Virtue Reality of the Cougar 366RDS. 2019. Screenshot by Rebecca Copper. Fig 8. (left) RV Living & Cooking: Social Practice Exercise. 2019. Screenshot by Rebecca Copper. Fig 9. (right) Justin Maxon drinking an imaginary beverage. 2019. Screenshot by Rebecca Copper.

My work as a social practice artistsocial practice became a means to reconcile my own usefulness to the community and offer a platform to strengthen the bonds of my neighbors, which is still ongoing today. As I continue to work inwardly, I started to think outwardly towards a secondary/tertiary audience and what empathy and involvement they could participate in. SSince story-telling was at the root of every exchange:; a concept that was considered when implementing RV Living & Cooking: Social Practice Exercise when participants of the History of Social Practice 2019 class took a virtual reality tour of my rig and were tasked tasking them to complete a family meal within the confines of simple lines marked on the floor. The participants had to collaboratively fabricate dinner for virtual guests who were coming over and the challenge of seating everyone somewhere within the RV. I wanted imagination to take hold of my participants as they carried on the familiarity of playing house, but ultimately humanizeing the experience of the RV community’s reality.

I have bonded with my new community through art and open dialogue, and watch the ebbs and flow of exchange that flourished naturally to create a co-existence of tolerance and sustainability within individuals, within a community and in society as a whole. It is an organic and imperfect process. Hhowever by changing my lifestyle by living atwith Hayden Island Relaxing Vacation Park Residence,; my mind and spirit has been freed.

Transactional Relationships

By Rebecca Copper

Rachael Anderson and Rebecca Copper together in Rachael’s apartment, photo by Left-Handed Sophie (2019).

In conversation with my friend, Rachael, the topics of authenticity and ingenuity often surface. Rachael, who is also an artist, is concerned about the lack of authenticity in the artwork they see as well as in the interactions they observe between individuals. I myself have concern for the lack of humility, humanity, and compassion that I witness in the interactions of people. During one conversation in particular, Rachael labeled these superficial interactions as “transactional”, or a relationship developed with the sole purpose of pursuing a goal, be it an expanded network or financial gain. In the discussion we continued to question how people alter how they behave and who they spend their time with based on this drive to receive something.

Currently, I am pursuing a contemporary practice of art through social practice. What drew me to this kind of artistic practice was an interest in the process of evolution as a focus of art-making in combination with valuing the space that exists in the interaction between individuals. I have worked in this medium for the past few years, but as I become more familiar with the role of the artist in social-cooperative artworks I question: where do these artists sit on a spectrum of substantial relationships and transactional, superficial relationships?

In many socially engaged artworks, the artist acts as an instigator or facilitator working with people or participants. This implies that for the artist’s project to be successful on any scale, there needs to be some kind of engagement from a participant or a number of participants. Therefore, this would categorize the relationships between artist and participant as transactional, seeing as the engagement would benefit the artwork and artist.

From this point, I think it is important to define the terms substantial, superficial, transaction, and relationship. Lexico.com (n.d.), which is powered by the Oxford english dictionary and is often what you’ll find when you Google definitions, defines substantial as “of considerable importance, size, or worth.” Substantial is also defined as “real and tangible rather than imaginary” (Oxford, n.d.). Superficial is defined as “appearing to be true or real only until examined more closely” (Oxford, n.d.). Transaction is defined as, “An instance of buying or selling something; a business deal” (Oxford, n.d.). It is also defined as “An exchange or interaction between people” (Oxford, n.d.). Relationship is defined by the same source as, “the way in which two or more concepts, objects, or people are connected, or the state of being connected”(Oxford, n.d.).

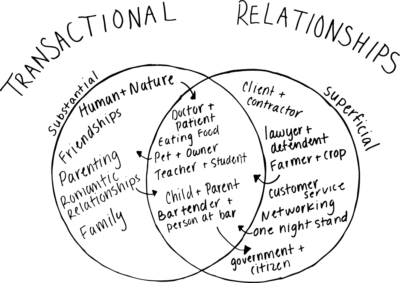

So, I’m left with my next question: are all transactional relationships unsubstantial or superficial? Personally, I usually don’t view things in a strictly binary perspective. I believe there is overlap in all areas of life and that truths blur together to create our very complex layers of experience. From this view, my answer is no. If not all transactional relationships are superficial, what do substantial, transactional relationships look like? Moreover, how does an artist ensure their practice leans more towards genuine and away from superficial transactional? I imagine that in our own web of relationships, examples of substantial, transactional relationships would be things like (but not limited to) parent-child relationships, romantic relationships, and mentor-student relationships.

If we were to create a Venn diagram of transactional relationships, it might look like this:

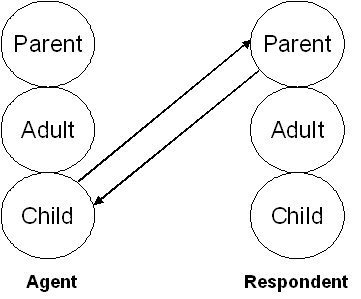

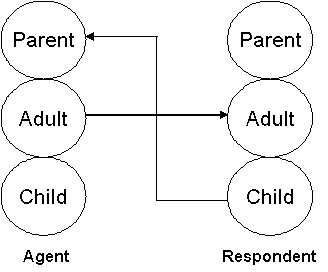

In researching transactional relationships on the internet, I stumbled across what is called Transactional Analysis. Transactional Analysis is the method of studying interactions between individuals that was developed by Dr. Eric Berne in the 1950s (International Transactional Analysis Association, 2014). Dr. Berne believed that transaction was the fundamental unit of social interaction. He also believed that the ego exists in three states, Parent, Child, and Adult. The Parent state is where an individual replicates behaviors or feelings that mimic what they observed their parents or act out parent-like roles. In the Child state, a person will act out in response through feelings and emotions in a similar way that they would have as a child. The Adult state is the last ego state that an individual exists in. In this state, a person has the ability to evaluate and validate information gathered through the Parent and Child states and to objectively observe reality. Dr. Berne believed that we all interact with one another through transactions with these three ego states.

Here are two diagrams pulled from a website dedicated to Dr. Eric Berne. These diagrams show two different types of ego states interacting, diagrams by Dr. Eric Berne (1964).

In the late 1960’s M.D. Thomas Anthony Harris, a student of Dr. Berne, published the self-help book, I’m Okay – You’re Ok: A Practical Guide to Transactional Analysis (Calcaterra, 2013). This title caught my eye because my husband, who has worked as an environmental education director of a transformational youth camp in the Appalachian foothills of southern Ohio, often referenced this model when working with youth who exemplified emotional responses due to unstable home environments. When a child was acting emotionally unsafe toward themselves or others, Al ,my husband, would say something like, “we need to get to a place where I’m okay and you’re okay. Right now, it looks like you are not okay, how do we get you to where we are both okay?”

Two kids from the youth camp, Camp Oty’okwa in the Hocking Hills of Ohio, photo by Al Marietta (2017)

The model outlined in Dr. Harris’s book consisted of four life positions that were based on Dr. Berne’s psychological set-up in his 1964 book: Games People Play: The Psychology of Human Relationships(Calcaterra, 2013).These four life positions are the following: I’m Not Okay, You’re Okay is the life position where an individual sees themselves in a weaker, unsafe position in comparison to others who they view as strong and more competent. I’m Not Okay, You’re Not Okay is the worst life position where an individual believes there is no hope, they see themselves and the rest of the world in a terrible state. I’m Okay, You’re Not Okay is where a person feels great about themselves but view others as weaker, less competent, or in a bad state. I’m Okay, You’re Okay is the healthiest life position. In this life position, the individual feels confident and good about themselves, and views others as good and competent.

When Faith Moves Mountains was a performance in Lima, Peru in which hundreds of volunteers shoveled a large scale sand dune from one place to another (Kester, 2012). The performance was orchestrated by Francis Alÿs in 2002 and was commissioned for the Lima Biennial. According to Grant Kester, the Los Angeles museum presentation of the performance “focused on the spectacle of the volunteers shoveling the sand” (p.68). He describes an image, “Alÿs, Medina, and Ortega all standing together at the performance site with bullhorns and cameras as they prepare to direct and document the labor of five hundred volunteers, mostly young college students from Lima wearing matching shirts emblazoned with the project logo” (p.69 ).

I would categorize When Faith Moves Mountains as a superficial, less substantial, transactional relationship. The artist instrumentalized and directed 500 people in unpaid, hard labor to create a symbolic gesture for an art audience in which the artist was paid and gained international presence. Furthermore, the volunteers were college students that were bused in to stage a performance that was supposed to criticize labor politics of a place without involving the population (Kester, 2012). “The dune was directly in front of a large shantytown with a population of over seventy thousand immigrants, displaced farmers, and political refugees. Few if any of the residents were involved in the project as volunteers. Instead, the town and it’s population functioned as a kind of backdrop, an image of the political ‘real’ (the impoverished, marginal space left to the victims of development and modernization) against which the metaphoric gesture of fruitless labor could take on added resonance” (p. 71).

I’d like to argue that Alÿs is taking the life position of I’m Okay, You’re Not Okay. Alÿs has assumed a role of power with his bullhorn in hand, dictating volunteers and students in a performance of hard physical work. Meanwhile, ignoring the people of the place that the project is supposed to represent. A perspective can be taken that the volunteers and residents of the nearby town were not left in a place of I’m Okay, where Alÿs left the project with more institutional clout and money. The unpaid volunteers were likely exhausted from shoveling sand for hours and the residents were not given agency but used as a superficial element to Alÿs staging. The ego state interaction which Alÿs falls within is likely one of the following two states: Parent or Child, or maybe a mix of the two. Alÿs mimics the role of a parent instructing the student volunteers, asserting his Parent ego state. Alÿs, also could be fulfilling his Child ego state by emotionally reacting to his poetic imagination or romanticizing the political issues around labor in Lima.

When interacting in the unstable ego states and the three unhealthy life positions previously mentioned, we pursue unsubstantial, transactional relationships. I’d like to push this further to advocate for socially engaged artists to be aware of their own ego states and life positions. If instrumentalization of people or participants is an element of conceptual rigor in a project, ensure that you are aware of it happening and why it is happening.

If you have thoughts, ideas, resources related to my questions and research please write to me OR if you just want to have a conversation :

References

Oxford University. (n.d.). Retrieved January 12, 2020, from https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/substantial

International Transactional Analysis Association. (2014). Retrieved January 12, 2020, from https://www.itaaworld.org/what-transactional-analysis

Description of Transactional Analysis and Games by Dr. Eric Berne MD. (n.d.). Retrieved January 12, 2020, from http://www.ericberne.com/transactional-analysis/

Calcaterra, N. B. (2013). History and impact of the book i’m ok – you’re ok dr. thomas a. harris. Retrieved January 12, 2020, from http://www.drthomasharris.com/im-ok-youre-ok-book-thomas-harris/

Kester, G. H. (2012). The one and the many: contemporary collaborative art in a global context. Durham: Duke University Press.

Rebecca Copper (b.1989) is an interdisciplinary artist that explores the space between symbolic and experiential, dialogical art. She is interested in using dialogue as a medium to shape experiences and as a way to explore collective learning processes. Deeply influenced by the ideas of Fluxus, bell hooks, and writings like the Society of the Spectacle, she supports blurring of art and life while removing hierarchical boundaries that keep art inaccessible. Rebecca has worked with people living in hospice, living under incarceration, as well as youth in some of her socially engaged art projects. She is currently in her first year as an MFA candidate at PSU’s Art and Social Practice Program and is a fellow through the Columbus Printed Arts fellowship. She received her BA from Otterbein University, where she focused on darkroom photography and experimental time-based media of which she pursues alongside her social practice.

Rooted in Relationship

By Emma Duehr

My houseplant practice is rooted in relationships. I began caring for plants after I moved away from my hometown and began searching for new signifiers of home and friendships. I ended up buying some of my mom’s favorite plants: hostas and impatiens, to help make my new house feel like home. This initiated my emotional connection to plants, as I grew to understand the sentimental importance, mental benefits, and self-care routine that is commonly associated with home gardening. I began collecting more plants by attending nurseries, buying from people on facebook, and exchanging clipping with people around Portland. This is how I ultimately began growing relationships with people in my new town.

Houseplants have been growing in popularity in recent years, which has created various plant community groups across the world. Plants are a growing collectible whose value is dependant on scarce supply, rare species, and age. Due to the rarity of certain plants and increase in demand, people have begun “proplifting” from nurseries, retail stores, and other public places; this refers to clipping off pieces of plants without permission from the owner. Some may call it a “green-collar crime,” others say it’s being resourceful. The act of taking clippings from plants is extremely resourceful because it allows thriving plants to duplicate and begin again in someone else’s life. You don’t need to steal from retail stores, because there is actually a large community of people who offer exchange, trade, or sell clippings from their own collection.

Gardeners and plant parents have traded clippings for years because certain plants have become status symbols and others hold sentimental value. This exchange happens between strangers on the internet, acquaintances at the same local plant swap, or it can be an extremely intentional and thoughtful gift from someone. One consistent component is an exchange of the plant’s history; it is important to share the plant’s history, story, and best care tips. Through this process, you’ll find that many plants have a story to tell. The original plant that has off-shooted new baby plants is commonly referred to as the mother plant; this terminology embodies the possibilities of sharing plants and the relationships that can be built.

My first plant became a piece of my family history. When my aunt’s cactus eventually reached the ceiling, she decided to trim, transplant, and gift pieces to different family members. I was one of the nine recipients. Kym states, “I have been cutting from this cactus for over 20 years! I would guess I have gifted these pieces to at least 20 people in my family. The original was my mother-in-law’s, which was born around 1990.” The passing down of plant clippings is a practice that many families and friends across the world practice. The symbolism of the plants’ roots embody the relationships that continue to coexist and add to the historical narrative. “I took many trimmings off it before it died around the age of 20, luckily many offsprings exist and are thriving in my childrens’ homes,” said Kym. A clipping from a plant that holds sentimental value is an invitation to a relationship that encourages health, growth, and connection.

I began asking for people to share their own family plant narratives and began archiving them online. Many narratives were shared about passing clippings of “family plants” and the influx storytelling that transpire from then. Brenda Mitchell is a recipient of a family plant, she said “I’ve had my Christmas Cactus for over 10 years. (Figure 2) It started as a scion* from my sister Barb’s cactus. She got hers from our Aunt Karen, who is now the caregiver of the first Christmas Cactus that came into our family over 60 years ago. This cactus was cared for and enjoyed by my Great Grandmother Dreyer. Around her death in 1960, it was passed on to her daughter who was my Grandma Klein. Around her death in 2001, it was passed to her son Dan’s wife Karen. Several family members have scions from the original or next generation plant. my mother received a scion from the family’s original Christmas Cactus in 1959, and she still cares for it today.”

Danica Shoffner received a clipping of a jade plant from her grandma when she was moving from her long-time home into assisted living. “I wrapped it up in a napkin and flew back home to Portland. It has grown much since and I hope one day to pass it down to other family members and share that it was from my grandmother.” She says “when I look at it or water it I think of my grandma and grandpa and what wonderful people they are/were. It gives me a sense of connection to them. Something living and growing that very well may live beyond me as well and continue to be shared and bring joy and connection.”

The sentimental value of plants can be from the relationships connected to it as well as the relationship you make with the plant itself. Plants communicate with their caretakers, and are proven to provide mental benefits and positive stimuli to the environment and the people within them. Getting dirty in a garden is a natural antidepressant due to the unique microbes in healthy organic soil. (insert source here) It is scientifically proven that plants make us happier and healthier. Plants can also provide metaphoric benefits for the importance of relationships, self-care, and suitable and healthy living environments. I took to the internet to ask specifically what plants do for different people. Facebook groups such as “Houseplant Hobbyists,” “Indoor Houseplant Group,” “Portland Plant Lovers,” Instagram, and my personal website were all platforms I created an interactive forum to gain research.

Nae Dumouchelle says “The greenery that fills the room allows me to feel more connected to nature within the walls of my home. It feels more lively and I am able to breathe a little better. Physically and spiritually. Mother Earth is our home and my door will always be open to her and the clippings that she continues to share with us.”

Britannie Weaver said “they are a reminder for me to take care of my mental health. When I notice I’m slacking or my plants look like they need love usually I need to take care of myself mentally too.”

“I love caring for all living creatures. Whenever I feel high anxiety or panic attacks, I start observing all my plants and seeing what they need and it helps calm me down. Plus, they are just beautiful! Why would you not want to be surrounded by natural beauty,” said Sara Campbell

Plants have filled the void in my life after my cat passed away. They need me…and respond to my care with gifts of bloom’s and beautiful new foliage. I need to be needed..and enjoy sharing plants with my loved ones, or really anyone that shows an interest in them. Great way to meet people also,” said Patricia Guidry

Roneal H. Torres says, “as a person who tends to procrastinate, having them made me become a lot more organized on how I consume my time. It taught me how to be a responsible individual.”

Do you have a family plant? What benefits have plants brought to your life? What sets your plant collection apart? I would love to hear, archive, and share your plant narratives. Send your thoughts to em.duehr@gmail.com or visit www.emmaduehr.com. *

Need propagation tips?

Most plants can be propagated into completely new plants by solely keeping them in water in the sunshine for about a month until the roots begin to grow. Not every plant likes excessive water, though tropical plants, succulents, and cacti are sure winners. Spring and Summer are the best seasons for successful propagation. Begonias, ctenanthe, peperomias, philodendrons, pilea, rhipsalis, and tradescantias are all types of plants that root well in water. Using a sharp edge, cut just below a node: the site where leaves grow from the stem. Cuttings should be about a foot long; larger clippings create an unhealthy ratio for demanding strong root system. Find a small glass jar such as a mason jar, vase, shot glass, etc. to fill with water. A smaller jar allows the plant’s hormones to be released into a lower volume of water which aids for quicker and controlled growth. Pick off any leaves that would touch the water; the leaves can rot and create affect the water quality. Patience is key.

Emma Duehr is an interdisciplinary artist who builds environments for community healing, empowerment, and education. Her work facilitates discussions, collaborations, and creativity using the worldwide web, educational settings, and city sidewalks. Her work is a platform for intimate exchange through gardening, craft, and dialogue. Emma is the creator of Talking Tushies; an ongoing international public art performance advocating for survivors of sexual violence. Duehr is based in Portland, Oregon and is pursuing her MFA in Art and Social Practice at Portland State University.

Between Generations: Learning through our difference

By Emily Fitzgerald

This morning, while on vacation in Mexico, I read a news article about a shooting in Florida. The article mentioned one of the victims, a 27 year old male UPS driver, who had picked up a shift and was caught in the crossfire. The story showed a photo of the victim’s grieving mother. At the end of passage, almost as an afterthought, a second victim was mentioned, a 72 year old man who also died while on his way home from work. I couldn’t help but wonder if this man’s age was the reason he was getting such a brief mention––as if he might have died soon anyway.

My husband used to work at a children’s hospital with state of the art facilities, and doctors and nurses from the highest caliber schools. He now works in skilled nursing at an assisted living facility for senior citizens, where he was hired straight out of nursing school. This facility, like many others, is desperate for nurses, especially those from high-caliber schools. During his training period they were so short-staffed, they called him in to work a shift on his own.

Both of these examples, among many others, leave me questioning the position of societies’ most experienced members of our culture. I would imagine that every young or middle-aged person would be interested in older people, considering that if we are lucky we are all going to experience being old one day. It seems that we would want to spend time with old people, if for no reason other than the fact that many people seem to want to know what to expect in the future. Or, perhaps a reason why generations are so segregated in the U.S. is that people are scared of the future, scared of growing old, and scared of dying.

Intergenerational work implies an exchange between different generations, but is typically understood as younger people working with senior citizens. How, as a society, do we define intergenerational work? Age may be the defining characteristic, but I wonder how much the desire really has to do with age, as much as difference of experience.

To me, intergenerational work has to do with understanding the perspectives of someone with a different personal, social, and political lens created by the passing of time. It has to do with learning from those who, in their many years, have (likely) made more mistakes than I have. It has to do with a relationship to time––which I seem to have no innate understanding of. And, hopefully, the longer you live, the more comfortable you become with change. I want to become more comfortable with change. Hopefully the longer you live the more comfortable you are with yourself. I want to be more comfortable with myself. I have talked to many older people who say they are now more comfortable in their own skin. I wonder if this is something young people can learn from elders or if we need to go through the process of aging in order to get there.

There is a societal perception that our value decreases with age. There must be a part of me that believes this, at least about myself, because as I prepare to leave my 30’s, I sometimes feel that my own value is decreasing. This is why personal exchange feels so valuable in this type of work. An older person that has been able to disregard harmful societal messages about value and become comfortable in their own skin has so much to teach us all.

So often with age comes lack of energy, decline of the body, and many other feelings that I want to avoid. There is no universal value that people of any generation provide, so I guess some of the value is in relating and listening to each other because we learn from understanding our differences.

I started doing what may be officially called intergenerational work when my Nonnie (grandmother) passed on. By that, I mean I worked with senior citizens that I wasn’t related to and brought groups of young people and older people together for different types of exchanges. I learned to use the term passed on, instead of passed away from the family of a wonderful 93-year-old who I worked with on a project. I like it more; it helps me feel like they are not totally gone. While working with seniors over the past five years, I have lost a lot of people I loved. Sometimes it is so easy to fall in love, especially with someone who has lived a very long time and has an ease of perspective that I always seem to be searching for. The sadness can take a toll after a while though; building relationships only to say goodbye so soon.

With my Nonnie, I had 34 years to build a relationship, to know her and to ask her questions. She was one of my soul mates. Our kindred connection seemed to transcend age, time, and dysfunctional family dynamics. With her I got to be myself. Someone seeing me in my best light helped me become the angel she thought I was. At least with her. She knew me before I guarded myself against loss and hurt and held that vision of me even when I didn’t feel it. I want everyone, young and old, to have an opportunity to be seen in their best light.

At some point I formalized the exchange with my grandma and we started working on a socially engaged photography and video project together. I documented my grandma’s life through photographs over the years. During the last year of her life I began to document our exchange, our relationship. I wanted to shift the power dynamic of me being “the photographer” and her “the subject”–– we both became photographer and subject. She took photos of me and I took photos of her. We staged images of us together and filmed our exchange. We sang songs and she wrote a children’s story. This collaboration supported our relationship and I think we got to know each other in new and different ways. So many things made us different, but it didn’t matter. There was a lightness and curiosity, rather than judgment of our difference.

How do we find and create more of these types of exchanges? Exchanges that add value to our lives and the lives of others? What does it mean to build that type of exchange between seemingly disparate people? How do we go about building alternate forms of exchange, interactions that are not built around transaction but on creating new paradigms, even if temporary? This is of endless interest to me––how to build or support infrastructures, environments, or relationships that encourage meaningful exchange, especially among people who are different from one another.

During an intergenerational project with youth from Beaumont Middle School and elders from Hollywood Senior Center I was interested in creating an exchange where youth and seniors could explore both the commonalities and differences between generations. As the creative producer of the project, I began by asking myself what my role was in bringing these two generations together, when I didn’t belong to either group? Wanting to make sure that the youth and seniors were directing the exchange, I started the project with seniors writing questions they wanted to ask the youth, and the youth writing questions they wanted to ask the seniors.

Similarly, I questioned how we were going to be able to dig deeper into more meaningful and intimate exchanges with a group of strangers when we only had six weeks together. An activity where participants mapped all the people and experiences that greatly impacted their lives helped guide the interactions in meaningful ways. Young people shared their fear of coming out as queer. Seniors shared how they understood the word ‘queer’. Students talked about depression and experiences with self-harm. One girl and older woman bonded over a love of the ukulele. One day a senior and youth came to our meeting in matching shirts. Both groups shared about people and loves that they had lost. Both groups shared their fears about the future.

After several projects that lasted less than a few months, I was ready to work on something longer-term. Molly Sherman, one of my collaborators and dear friend, and I were thinking a lot about the ways in which we, as young white artists living in NE Portland, were contributing to gentrification. We wanted to learn about our neighborhoods from people who really understood the history of this place. Our project, People’s Homes, paired longtime residents of NE Portland with local artists to create small-scale front yard billboards that shared the homeowners’ lived experience. That year we spent a lot of time in people’s kitchens and living rooms getting to know the homeowners and their families. Collaborating artists also spent a lot of time with the residents and created custom pieces for the homeowner’s front yards based on their exchanges. In addition to the front yard billboards, we created a newsprint publication featuring conversations between the artists and homeowners, project documentation, a map of the signage installations, biographies of the project participants, and interviews with art writer Lucy Lippard about her examination of art, place, and social engagement, and Norman Sylvester about his strong commitment to community and honoring the history of North and Northeast Portland. Since the project was completed in 2016, some of the older homeowners have passed away, people who had become so dear to me. I wonder if this kind of loss is a deterrent for people engaging in work with old people.

The senior from People’s Homes that lives closest to me is Paul Knauls. He just turned 89 on January 22nd this year. He has so much energy. In November he told me he hadn’t stayed home one Saturday night since May because he was invited to so many events and parties by his friends in town. He sends me photos of the new babies born into his family or moments when he is honored by another community plaque or mural. I stop in to see him occasionally and we chat at Geneva’s Shear Perfection, the barber shop he owns. We talk about his granddaughters, my work, what he is doing in the community, and anything funny that has happened to either of us since we saw each other last. He works at the shop seven days a week greeting people with his contagious laugh and exuberant smile.

When I returned from my vacation in Mexico about a week ago, I felt the weight of a return to the Pacific Northwest during the darkest days of winter. I wasn’t really excited to be back here and was missing the way strangers interact more freely when the sun is out, or in smaller communities. My husband and I went to the grocery store and the first person we ran into was Paul. His huge smile reminded me that this place isn’t so bad afterall. During our short catch up I noticed he was holding on to the shelf next to the Opal apples, his favorite. I guess in your late 80’s, your balance isn’t the best. He seems so youthful, but even if he lives to 100 he is still nearing the end of his life.

This exchange reminded me of the importance of knowing and sharing life with people of different generations––not just youth––but people much older than us as well. In our neighborhoods. At the grocery store. People that we have grown to know. It made me realize that without structures that encourage intergenerational exchange many of us might only know the elders in our own families. I continue to wonder how to build projects that encourage others to foster ongoing intergenerational exchange? How to get people to question the age segregation that exists? How to get people to think about what may be missing in a society that is so segregated by age? And how can we make these questions relevant to people of all ages? Age may be the defining characteristic of intergenerational work, but the value really lies in the depth of experience and perspective that comes with learning through difference.

Emily Fitzgerald is a creative consultant, socially-engaged artist, photographer, and storyteller. Through her consulting and art practice she focuses on integrating the relational and visual to elevate engagement, invoke curiosity, and demonstrate multi-dimensionality. Her work is responsive, participatory, and site-specific—seeking to shift systems of power, and build meaningful connection. Emily brings large-scale art installations into non-traditional, public and unexpected places in order to deepen our understanding, reframe our ways of relating to one another. In addition to creative consulting, Emily teaches Art and Human-Centered De- sign at Portland State University.

(Des) Conectividad en Cuba: La Ruta del Paquete Semanal

Por Aurora Rodriguez

Por mucho tiempo, la gran plaza pública cubana de medios ha sido ocupada principalmente por las fuentes estatales, que han centralizado voces diversas en coherencia con los preceptos y códigos ideológicos promovidos en el proyecto social del `59 con énfasis en mensajes políticos, informativos y educativos. Sin embargo, Cuba no está exenta de las transformaciones sustanciales que se han experimentado globalmente en el orden de las comunicaciones en los últimos años. Es por ello que el caso cubano resulta extremadamente interesante si de usos, alternativas y acceso a Internet se trata. ¿Qué es el paquete semanal? ¿Cuáles han sido las condicionantes que han generado su aparición? ¿Es un fenómeno exclusivamente cubano? ¿Podrá el paquete semanal sobrevivir la entrada de Internet a Cuba? A estas y otras interrogantes dará respuesta el presente artículo.

El punto de partida: ¿cuál fue el origen del paquete semanal?

Se dice que los cubanos son una especie humana muy particular. Y es que su particularidad comienza en esa naturaleza creativa que los caracteriza, como respuesta instintiva a la precariedad. La historia de este país de los últimos 60 años se ha visto fuertemente marcada por una escasez material que ha potenciado entre otras cosas, el valor espiritual de los nacidos en la isla y su permanente inventiva.

No se sabe realmente si el paquete semanal es un producto auténticamente cubano. Seguramente en diversas zonas con difícil acceso a la Red de Redes se podrán detectar soluciones similares. Pero de lo que si se está convencido es que el alcance y la magnitud que tenido en todo el país, es algo que lo convierte en un fenómeno único. Para entender los por qué, se hace necesario conocer un poco de la historia, condicionantes y detonantes que distinguen esta realidad infocomunicativa.

Descifrar las particularidades del acceso a Internet, nos obliga remitirnos a circunstancias inherentes al contexto cubano: bloqueo económico de los Estados Unidos, crisis sistémica de los años ´90 -con fisuras aún latentes en la economía-, economía limitada con deficiencias en la producción nacional, una dependencia a la importación de productos de cualquier índole, centralización de los recursos, burocratismo, etc. provocan que el acceso a Internet esté fuertemente condicionado por coyunturas espacio-temporales, así como por voluntades políticas.

Desde la temprana fecha de 1962, Estados Unidos ha prohibido el acceso al país de hardware y software de procedencia estadounidense. Situación que genera un encarecimiento de los dispositivos al tener que comprarlos por medio de otros proveedores. En el “Informe de Cuba contra el bloqueo” se valoraron las pérdidas causadas sólo en el período de abril 2018 a marzo 2019 de 4.343 billones de dólares. De modo que es innegable el impacto que este factor puede generar en la economía general y en especial en el renglón de las comunicaciones.

Se produce como respuesta desde Cuba una especie de “sobredimensión de la percepción de riesgo de Internet”. De modo que a inicios, existió un recelo desde la alta dirección por dar pasos decisivos en la implementación de políticas de libre acceso a la red. A esta condicionante se le suma que la entrada en Cuba de las nuevas tecnologías coincidió con la profunda crisis económica de la década de 1990.

Coordenadas para una definición: ¿Qué es el paquete semanal?

En Cuba, según datos de la Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información, sólo 257 personas de cada mil habitantes tienen acceso a Internet. Si bien, la conectividad en Cuba ha progresado a raíz de las más recientes prestaciones ofertadas por la compañía de telecomunicaciones cubana ETECSA, con la conexión a través de redes móviles, correo móvil, wifi en distintos puntos del país, etc., la cifra de ciudadanos que acceden a Internet y a redes sociales hoy en Cuba es todavía limitada. Como también son restringidos los sitios de accesos posibles desde un “estrecho” de banda.

A la luz de estas dificultades, ha florecido de soslayo, una alternativa que figura las primitivas vías de comunicación en las que el hombre, sin depender de la tecnología, se comunicaba de forma directa, cara a cara. Es así que semanalmente se movilizan a lo largo y ancho del país, hombres y mujeres con el fin de “copiar” o distribuir al menos 1 terabyte de información compuesta por videos (Filmes HD, Filmes Cubanos, Filmes Clásicos, Videos Youtube…), música (Música Nacional, Música Internacional), programas de participación, literatura (Revistas, Libros…), clasificados de compra y venta, etc.

“El paquete semanal es el resultado de la capacidad inventiva del cubano ante las limitaciones de acceso a internet, la ausencia de televisión por cable y de otras opciones que existen a nivel internacional para la difusión de mensajes culturales”, asegura el ex Ministro de Cultura y actual Presidente de la Casa de las Américas, Abel Prieto.

El paquete resulta ser la solución semi-artesanal, momentánea y relativamente económica, ante la ausencia de una plataforma masiva que conecte a los cubanos con la información generada diariamente en la web. Una excepción en una globalidad distinguida por la conectividad, cuya esencia consiste precisamente en el intercambio de información.

Información que se compra por un precio de 2 CUC (peso convertible cubano) y se recibe todas las semanas hasta la puerta de la casa. Un home delivery del cual los usuarios escogen y copian en su ordenador lo que consideren interesante. Las amas de casa copian sus novelas, los niños juegos de consola y los aficionados al cine logran acumular cientos de gigas de sus películas favoritas.

Aunque pocos conocen su origen real, el paquete se ha convertido en un repositorio multimedial, que cada usuario logra “costumizar” de acuerdo a gustos, intereses y preferencias, a manera de comunicación a la carta, o internet “empaquetado”.

En términos mercantiles, a través de “el Paquete” se han visto favorecidos muchos negocios nacionales, debido a la utilización de este espacio, como trampolín divulgador de mensajes promocionales. En este sentido, “el Paquete” ha permitido establecer un puente de comunicación no institucional y emergente entre todos los cubanos.

En su interior residen además una suerte de “contendedores” digitales para anunciantes como “Revolico”, “Porlalibre”, “Popularisimo”, etc. en los que se ofertan una amplia gama de productos y servicios para casi todos los gustos, intereses y preferencias. De modo que esta herramienta impacta ostensiblemente en el florecimiento de una especulación interna “subterránea” a los canales oficiales de comercialización.

Y es que “el Paquete” no es un ente casuístico. Detrás de cada terabyte de información que circula, existe un grupo de hombres o mujeres, creadores y gestores que son movidos por intereses y objetivos, hasta la fecha desconocidos, debido a la conveniente nebulosa que encierra su dinámica de funcionamiento interno.

Tampoco existe información precisa sobre cuántos paquetes son distribuidos semanalmente a lo largo y ancho de todo el país. Se desconoce además quienes son sus distribuidores. Muchos se preguntan cuál será el mecanismo que utilizan para lograr descargar 1 TB de archivos con la lenta conexión que existe en Cuba. Algunos especulan que llega directamente de los Estados Unidos. Y es que como la mayoría de los productos que circulan de forma clandestina en cualquier parte del mundo, existen “vacíos” informativos y legales que son los que permiten que dichos mecanismos continúen y sus responsables no sean identificados.

Relacionado con la definición de sus contenidos, aunque el paquete responde a una dinámica de libre fluir de la información, si se pueden trazar criterios de autocontrol de la información, de modo que ningún proveedor incluye dentro de sus “carpetas” pornografía o materiales políticamente incorrectos para evitar ser censurados o descontinuados.

Asimismo, los estudiosos del paquete semanal han logrado construir la cadena de distribución que hace posible su circulación: partiendo de los proveedores quienes reproducen la información a las matrices, quienes copian directamente a los distribuidores de primera mano, a quienes luego a su vez copiarán a pequeños distribuidores, para que finalmente llegue a manos de los consumidores.

Ahora bien, ¿por qué esta fórmula de apariencia tan simple alcanza tal impacto?

Primeramente, se debe partir del escenario mediático cubano que, como ya se ha mencionado, se distingue por políticas, estructuras y agendas constreñidas al aparato estatal. En la que cabe destacar la poca presencia, hasta hace algunos años, de materiales de procedencia extranjera; sin desconocer con ello, la cultura de dramatizados y filmes foráneos, que si se ha acostumbrado a trasmitir por las vías formales.

Acompañando esta constricción en la distribución cultural, la parrilla de programación mediática nacional se vio también deprimida como reflejo de la desnutrición que experimentaban los presupuestos de la producción audiovisual en plena crisis. Y como resultado, el televidente cubano sólo tenía para su esparcimiento escasos canales de televisión con programa de muy baja calidad en su confección y en algunos casos en su dramaturgia. La audiencia cubana, necesitada de una alternativa que la transportase hacia entornos completamente ajenos a los problemas que diariamente debía enfrentar, comienza a rentar por horas las antiguas cintas de video VHS, los CDs, VCDs y DVDs que contenían novelas, películas y shows latinos grabados de la “antena” (trasmisiones ilegales que algunos cubanos tenían en sus casas por medio de aparatos receptores que tomaban la señal trasmitida desde los Estados Unidos de televisoras americanas). El paquete semanal es por tanto, una forma mutante de lo que otrora fuesen estas alternativas multimediales bien demandas por los cubanos de a pie.

Agregar además, la poca experiencia en términos de producción y consumo de publicidad, que por política nacional hasta hace unos pocos años había sido desestimada, incluso por la academia, al considerarse una materia apegada a la ideología capitalista y consumista, ajena al proyecto socialista en construcción. No obstante, a principios de los 90, como estrategia de país para sortear la crisis económica que devino el derrumbe del campo socialista, se comenzó con discreción a coquetear con la publicidad como herramienta poderosa para el desarrollo del turismo. Actualmente, a partir de la concurrencia de nuevas formas económicas luego del VI Congreso del Partido Comunista de Cuba, el país se encuentra en franco despertar de las comunicaciones promocionales.

Dicha publicidad es pagada y resulta una de las formas más lucrativas del “negocio” del paquete. A raíz de la apertura del gobierno a la creación de negocios privados, numerosos cuentapropistas cubanos pagan a los creadores del paquete por anunciarse y es así que a lo largo de la gran diversidad de subcarpetas que contiene el paquete, encontrará el usuario alusión directa a una oferta concreta, bien por su colocación a finales de cada material o con cintillos insertos en cada video. Se ha creado una especie de compañía de las comunicaciones a espaldas de la oficialidad, que en estos momentos domina el escenario publicitario cubano de forma incontrolada y con no pocos dividendos.

La garantía de éxito de “el Paquete” ha sido la posibilidad de ejercer una libertad de elección, sobre las condiciones que determinan el consumo: lugar, horario, programación, dispositivos de reproducción: móviles, ordenadores, tablets, etc., así como de los formatos: dramatizados, filmes, series, videos Youtube, entre otros.

Este medio alternativo representa además una vía mediante la cual los sujetos logran sentirse conectados con resto del mundo, para conocer temáticas de actualidad, ya sea tecnológica, musical, cinematográfica, seriada o fashionista, que le permitan ejercer un derecho elemental común a toda la humanidad: la necesidad de estar/mantenerse informado.

Y es que en efecto, la “realidad” que nos presenta “el Paquete” es muy diversa, pero también muy diferente a nuestra cotidianidad. Envíos internacionales, compras on-line, tiendas y productos para cualquier necesidad, tecnología de punta, etc. ¿Cómo no conmoverse ante “bondades” como estas, que le facilitan la existencia a muchas personas actualmente, más aún cuando muchos cubanos “subsistimos” ante disimiles carencias de tipo económica? Ante ellas, resultan increíbles las otras verdades… las de los desconectados, los sin acceso, los no personas…

El camino desandado: ¿cuál es el futuro del paquete?

¿Desaparecerá el paquete si se lograse extender el acceso a Internet en Cuba? Considerar que la muerte del paquete –si realmente fuera posible- se encuentra ligada exclusivamente al acceso liberado a la Red de Redes, es concebir a uno como el sustituto del otro, y esta es una consideración errada. De la misma forma que el paquete no pudo, ni ha podido sustituir a Internet, pensar en una suposición a la inversa, tampoco es posible.

Se habla pues de dos plataformas diferentes: Internet, medio interactivo por excelencia, que atraviesa la totalidad de las acciones de la vida cotidiana del hombre/mujer de nuestra época y desborda la función informacional que caracteriza al paquete semanal como mero repositorio y medio para el consumo multimedia. De modo que se debe hablar en vez de una sustitución de una convergencia, en la que conviven ambos medios en el basto ecosistema mediático cubano.

Al igual que el resto de las sociedades, Cuba necesita adaptarse a la convergencia sin precedentes en la experiencia socialista, que le permita avanzar en el modelo económico-social humanista en el cual se ha involucrado hace más de cinco décadas.

La gestión mediática en un escenario de convergencia supone la anuencia de procesos de hibridación y sinergia que posibiliten el acceso para la producción y consumo de contenidos en dispositivos cada vez más portátiles, interactivos y multimediales.

Continuarán quienes sigan consultando al paquete. Probablemente, en un futuro lejano o no, aparezcan otras plataformas que revolucionen las comunicaciones en todo el mundo y quizás ya no le nombremos igual, pero de seguro, existirán nuevas formas que continuarán con la larga tradición del cubano de inventar y así perseverar.

Referentes:

- Cubadebate “Escaneando el Paquete Semanal”, www.cubadebate.cu

- Campos, Z. (2014) Cartografías de la Desconectividad, Tesis de Licenciatura en Comunicación Social, Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de La Habana.

(Dis)Connectivity in Cuba: The Route of El Paquete

For a long time, the Cuban media landscape has been occupied, principally, by state-run sources. These sources have centralized diverse voices in accordance with the precepts and ideological codes promoted by the social project of ‘59, with an emphasis on messages that are political, informative, and educational. Nonetheless, Cuba is not exempt from the substantial transformations that have been globally experienced within the realm of communications in the past few years. It is for this reason that the case in Cuba has incredibly interesting results in terms of use, access and alternatives to the internet. What is el paquete (the paquete)? What have been the conditioning factors that generated its appearance? Is it an exclusively Cuban phenomenon? Will el paquete be able to survive the entrance of internet to Cuba? To these and other questions this essay will respond.

The point of departure: what was the origin of el paquete?

It is said that the Cubans are a very particular species of human beings. This particularity is characterized by a certain type of creative nature, that comes as an instinctual response to precarity. The history of this country in the last 60 years can be seen clearly marked by a material scarcity that has maximized, among other things, the spiritual value of those born on the island, and their continual inventiveness.