Uncategorized

Visiting Scholar Lydia Matthews

Lydia Matthews is a Brooklyn and Athens-based critical writer, contemporary art curator, educator and cultural activist who currently serves as Professor of Visual Culture in the Fine Arts program of Parsons School of Design and Director of the Curatorial Design Research Lab at The New School. Trained as a contemporary art historian at the University of California, Berkeley and the University of London’s Courtauld Institute, her work focuses on the intersection of current art/craft/design practices, diverse local cultures and global economies. Thus far, she has been invited to design curatorial ventures in New York, Greece, Turkey, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and the Czech Republic.

Before relocating to New York in 2006, she taught for 17 years at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco. There she co-founded and chaired the graduate program in Visual Critical Studies and co-directed the MFA program in Fine Arts, which launched the first MFA program in Social Practice in the United States in 2005. From 2007-2012, she served as Dean of Academic Programs at Parsons, facilitating a restructure of the school and a collaborative, faculty-led re-design of the undergraduate curriculum to promote cross-disciplinarity and empower students to better respond to the conditions of today’s complex global arena. In 2011 she launched the Curatorial Design Research Lab (CDRL) across The New School, thus establishing a network of multidisciplinary colleagues dedicated to exploring the intersection of curatorial, pedagogical and activist practices. The Lab’s current project, I Stand In My Place With My Own Day Here: Site-Specific Art at The New School (forthcoming book/website, 2019) features the writing of over 50 authors–including Claudia Rankine, Lucy Lippard, Holland Cotter, Maggie Nelson, and others—demonstrating how a collection of commissioned artworks can embody and inspire polyvocal narratives over time.

Adrian Ruth Williams

Adrian Williams (she/her, b. 1979, Portland, Oregon) is a transdisciplinary artist and writer invested in various forms of language. Her practice involves voice, text, sound, video, photography, performance, and the immersive handling of space. Employing conceptual narrative structures, her work revolves in both literal and fictitious arenas, fielding the conditions that determine form to explore the form of the human condition.

Williams’ work has been exhibited internationally at institutions including the 21er Haus, Vienna, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Portikus, Frankfurt, Artpace, San Antonio, Art Production Fund LAB, New York, GAM – Galleria Civica D’Arte Moderna E Contemporanea, Turin, MACBA, Barcelona, the Athens Biennial, Athens.

Williams received a Bachelors degree from the Cooper Union, New York, and is a Meisterschulerin of the Städelschule, Frankfurt. She resides in Frankfurt, Germany and is a doctoral candidate at the University of Applied Sciences (HFG), Offenbach, writing about voice.

Manfred Parrales

I am a Latin art communicator from San Jose, Costa Rica. I believe in communicating through and by art.

After graduating from the Art School of the University of Costa Rica, my interest as a designer and art enthusiast is in creating art communications solutions/experiences around the use of technology.

I have 6+ years of experience in design and visual communication in the technology industry with several expressions in video, design, and photography. I created videos for Costa Rican rock bands, art videos, as well as educational videos about art topics and art history.

+ Take a look here

+ Instagram here

Ashley Yang-Thompson

The product of a Chinese immigrant and a white polygamist from Fort Scott, Kansas, Ashley Yang-Thompson has been a performance artist since the day she was ruthlessly shoved out of the safety of her mother’s womb. She works in a wide range of media, from figurative painting and zines to Diogenes-style performative pissing. Her art has been exhibited at the San Francisco Asian Art Museum, the Museum of Moving Image, and the Essex Peabody Museum (Spring 2023), as well as numerous national and international spaces. She is a recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts Creative Equity Fellowship and Mass MoCA’s Assets for Artists Grant. In 2021, Bateau Press published her graphic novella, How to be the worst laziest fattest most incontinent piece-of-shit in the world EVER.

Worm Slut

A collaboration with Nia Musiba

Zine collection 2022

WORM SLUT, a collaboration with Nia Musiba, is a Portland-based risograph zine that confronts issues of identity, as well as which barroom bathrooms are transgender nightmares, diurnal bowel movements, and the best breakfast burrito in Portland (an ongoing investigation). Nia and I started the zine in February 2022, and have 13 issues. We freely distributed 250 copies of each zine at various local coffee shops and throughout the PSU campus, with open calls for participation. Worm Slut is our personal invitation to the world: please be the weirdest version of yourself around us. It is our love letter to the lonely and our inoculation against the shrinking human being inside each of us.

Jane Fonda’s Original Workout / “Flex” Factory

Ever since 2016, I have done Jane Fonda’s Original Workout (the best-selling VHS of all time) almost every day. In an era where women were discouraged from exercising and gyms were dominated by men, Jane Fonda’s Original Workout (1982) was groundbreaking. It popularized fitness for women (as well as a neon spandex fashion craze), and the proceeds supported leftist political organizations. During my residencies at Vermont Studio Center, The Wassaic Project, and Oxbow School of Art, I made Jane Fonda’s Original Workout into a daily happening, and invited residents and staff to participate in this iconic aerobic ritual. In the heyday of Equinox, Class Pass, and the disgustingly remunerative Cult of Health, Jane Fonda’s Original Workout functions as a free, silly, and moderate group workout that only requires a towel. The workout attracted a heterogenous group of residents, including Cheryl R. Riley, who actually did Jane Fonda’s workout with Jane Fonda in the 80’s. In 2019, I was asked to lead Jane Fonda’s Original Workout (advertised as a “queer comedic fitness demo”) at Socrates Sculpture Park in Astoria, NY as part of Flux Takeover!

Video made in collaboration with Zehra Khan

Cognitive Disobedience (and the right to be Lazy)

Syllabus:

please contact me if you are interested in enrolling in this course:

contact: ashley.yang.thompson@gmail.com

website: ashleyyangthompson.com

newsletter: ashleyyangthompson.substack.com

Assembly 2022

Friday, June 3rd – Sunday, June 5th

Event Schedule with project descriptions

Friday, June 3rd

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 12:00pm – 12:50pm | How to Make Friends: Advice From Some Fourth Graders | Olivia DelGandio & Ms. Bre’s Class | Library at Dr. MLK Jr Elem School + Zoom | Participatory |

Making friends is hard! Let’s go back to school and learn the basics. We’ll start the hour by viewing a video featuring Valerie, Angelica, and Norma, students in Ms. Bre’s fourth grade class. Together, they’ll guide us through the essential questions to ask when getting to know someone. The video will then be followed by a collaborative exercise where Ms. Bre’s fourth graders will be paired up with the attending adults to practice the art of making friends!

Homework Assignment

Come up with your own list of questions essential to getting to know someone. Ask them to a stranger.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 1:00PM – 1:50PM | Art Forgery Club | Caryn Aasness & Students | Library at Dr. MLK Jr Elem School + Zoom | Workshop/Play |

Make your mark on the KSMoCA Art Book Library. In small groups, we will choose images of works of art from the books in the library collection that stand out to us. Then, we will recreate them with our own bodies and some provided props. The resulting images, our altruistic art forgeries, will be included in the art book library for visitors to see and admire!

Homework assignment:

Can you picture a work of art in your head? Try to draw it or recreate it with your body from memory without looking it up. When you are done look up the original and see how close you got in your recreation.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 2:00PM – 2:50PM | IAC: The Stone | Diana Marcela Cuartas & Illia Yakovenko | The Halls of KSMoCA | Show Opening |

The International Acquisitions Committee presents The Stone: an exhibition opening and a screening of the original work. The Stone is a video performance by Ukrainian artists Anna Sorokovaya and Taras Kovach. It was inspired by 7000 Oaks by Joseph Beuys and is about monuments, the environment, and feelings of disorientation due to the current war, occupation, and displacement in Ukraine.

This artwork got picked by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. School students to become part of the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. School Museum (KSMoCA) art collection and was featured at Fred Hampton Summer Camp. The exhibition features materials that provide further insight into The Stone: the surrounding context, its history, and meaning. The exhibition and event was curated in collaboration with Diana Marcela Cuartas.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 3:00PM – 3:50PM | The 5th Grade Safety Patrol High Vizibility Crosswalk Spectacutlar | Becca Kauffmann & Mo Geiger and MLK Jr School Crosswalk Crew | Dr. MLK: the rainbow crosswalk by the soccer court at NE Grand Ave and Humboldt St | Public Performance |

What and who do we want to make more visible? In the case of the Dr. MLK 5th Grade Safety Patrol, the answer just might be: each other. Every day from Monday to Friday during the school year, these volunteers suit up in high visibility garb to help their fellow students safely cross the street to and from school. Join us for the first annual Hi-Vizability Crosswalk Spectacular, the grand finale of our month-long collaboration with the Safety Patrol team in which they’ll debut their flagging routine on a freshly painted guerilla crosswalk while decked out in brand new customized hi-viz attire.

Special thanks to Niek Pulles and the Nike materials lab for their textile donations.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 4:00PM – 4:50PM | Artist Talk with Moe and Luz | Luz Blumenfeld & Moe | Library at Dr. MLK Jr Elem School + Zoom | Conversation |

Let’s talk about art baby, let’s talk about you and me,

If you have any questions that you specifically want us to answer, please email them to Luz at lublu2@pdx.edu prior to the event on June 3rd, 2022.

Homework assignment:

- Interview someone you see every day. This could be your parent, child, someone you see everyday at the coffee shop,

- Ask your favorite artist some questions.

Saturday, June 4th

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 10:00AM – 10:50AM | Persona Muy Importante – VIP Tour | Diana Marcela Cuartas | Touring all around the Museum – there is a table in the hallway/ entry | Tour / Visita guiada VIP |

Acompáñenos en una visita guiada exclusiva en español por las instalaciones del Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de la Escuela Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. de la mano de Diana Marcela Cuartas, artista Colombiana y estudiante de 2do año de la maestría en Arte y Práctica Social de la Universidad Estatal de Portland.

Tendremos una pequeña recepción, presentaremos la colección permanente y algunos de los proyectos que se desarrollan dentro este museo-escuela como el Comité de Adquisiciones Internacionales y el trabajo de la artista en residencia Lucía Monge (Perú).

Todas las familias y vecinos de la escuela que hablen español son bienvenidos a conocer de cerca este espacio de creación artística y conectar con otros miembros de la comunidad que comparten el idioma.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 11:00AM – 11:50AM | The Art We Value | Shelbie Loomis | Library at Dr. MLK Jr Elem School + Zoom | Graduate Lecture |

What in our lives can be considered art? What makes art valuable?

Shelbie Loomis will be giving her graduate lecture about her work leading up to The Art We Value, a socially engaged art project with portraits, interviews, and ongoing exchanges that explores how twelve neighbors living in Jantzen Beach RV Park and Hayden Island Mobile Home Community in North Portland think about art in their lives.

She will be exploring methods of working through exchange such as drawing, conversations, and spending quality time with residents in her neighborhood. And explaining threads of common artistic research and other projects around topics of home, art, and monetary value versus intrinsic value around objects.

The Art We Value is produced in collaboration with Alice Smith, Michael Smith, Dago Sanchez, John Ingels, Greg Hatley, Michelle Grimes, Cecilia Saucedo, Chris Emery, Sam Churchill, Benita Alioth, Carroll Kachold, and Herman Kachold.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 1:00PM – 1:50PM | 🏀 N-E-I-G-H-B-O-R 🏀 | Lillyanne Pham and Lo | Dr. MLK Outside Basketball Court | Basketball Game |

Join 🏀 N-E-I-G-H-B-O-R 🏀 , a basketball game filled with playful competition collaboration. Let’s bond through sweat! We will collectively make 8 ball shots to spell NEIGHBOR as many times as we can within the hour. After every ball shot, we will practice getting to know each other through questions made by Lomarion and Lillyanne.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 2:00PM – 2:50PM | Field Guide to a Crisis and Chester: Staring Down the White Gaze | Justin Maxon | Virtual | Graduate Lecture |

Justin Maxon (he/him) will be presenting his graduate lecture about his practice and the two projects he developed during his time in the Art & Social Practice program: “Chester: Staring Down the White Gaze” (a book project in collaboration with Dr. Herukhuti Willams, and Chester, PA artists Desire Grove, Wydeen Ringgold, and Leon Patterson); and “Field Guide to a Crisis,” (a skill development training program in collaboration with people in recovery from substance abuse in his hometown of Eureka, CA). Both of which have helped him reconcile his relationship to power and privilege as an artist who is racialized as white.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 3:00PM – 3:50PM | Invitation to Rest | Marina Lopez + Clara Takarabe | Virtual | Time to rest |

An Invitation to Rest is co-facilitated by Clara Takarabe and Marina Lopez. Let’s be honest, life is a lot right now and the capitalist grind and concurrent crises has us all in dire need of a long, restorative nap. Bring your cozy clothes, your weary bones, and come ready to relax.

During this session, your rest facilitators will use Clinically Designed Improvisational Music developed by Clara and the research team at Northwestern University paired with simple movements that signal to your brain and body that you are safe; shifting your nervous system from a state of fight or flight into a restful state of restoration.

This session seeks to disrupt habitual patterns in our brain and body as a means of disrupting social, economic, and political systems that perpetuate harm across sinew, psyche, and generations. Come experience how rest can be a place of endless possibility, transformation and even revolution.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 4:00PM – 4:50PM | I Want Everyone to Know with Ms. Melodie Adams | Laura Glazer & Ms. Melodie Adams | Library at Dr. MLK Jr Elem School + Zoom | Interview and Presentation |

First grade teacher and community leader, Ms. Melodie Adams, will share what she wants everyone to know in a keynote interview with Laura Glazer followed by a celebration of the book by Laura called I Want Everyone to Know, The Black History Month Doors at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School. The book features an extended interview with Ms. Adams.

| 5:00PM – 5:50PM | Book Launch | Laura Glazer & Ms. Melodie Adams | Library at Dr. MLK Jr Elem School + Zoom | Book Signing/Ceremony |

Sunday, June 5th

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 10:00AM – 10:50AM | SoFA Journal Release Party | PSU Art and Social Practice Program | Library at Dr. MLK Jr Elem School + Zoom | Journal Release |

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 11:00AM – 11:50AM | Self Care Zine Workshop | Kiara Walls and Lillyanne Pham | MLK Parking Lot | Workshop |

Join zine expert Kiara Walls and Lillyanne Pham in a community “self-care zine”. Each participant will create a page about self care using their choice of materials (collage, paint, drawing, etc.) to be added to a published Zine about self care to share with our community.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 12:00PM – 12:50PM | Lens-based Practices & Socially Engaged Art | Rebecca Copper | Library at Dr. MLK Jr Elem School + Zoom | Graduate Lecture |

Rebecca will discuss her artistic practice and the research that evolved over the course of her graduate studies at Portland State University within the Art and Social Practice MFA program. The presentation will cover work such as the development of site-specific projects that occurred at Colonial Hills in Worthington, Ohio and the Single Parent Archive, of which Rebecca co-founded with Marti Clemmons. Rebecca will discuss methodologies that connect her socially engaged work to her lens-based practices.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 2:00PM – 2:50PM | Collective Doing | Mo Geiger | Library at Dr. MLK Jr Elem School + Zoom | Graduate Lecture |

In this lecture, graduating student Mo Geiger will present her most recent work as part of a path toward collective doing and thinking. Her interdisciplinary and often collaborative projects blend interpersonal relationships, physical material, craft, and multimedia performance. In this narrative talk, Mo will describe relationships made while bottle-feeding lambs, weaving in public on a handmade loom, planting seeds for a day in Oregon, performing on a lakeside in Pennsylvania, and hiding a secret capsule in the Pennsylvania State Capitol Building. By performing shared labor in her immediate surroundings, she explores embodied knowledge and the ways that her collaborators’ routines, passions, and knowledge can be windows into unfamiliar ways of relating.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 3:00PM – 3:50PM | The Gatherade Stand 01 | Giliian Rappaport and students from Ms. Johnson’s 5th Grade Class | Library at Dr. MLK Jr Elem School + Zoom | Interactive Installation |

The Gatherade Stand is a co-authored art project in the form of a lemonade stand that serves drinks* made from wild-foraged plants and creates opportunities for collaborative creativity centering those same plants.

Lead Artist and Naturalist: Gilian Rappaport

Artist, Teacher and Collaborator: Ms. Johnson

Artist, Audio Composer and Collaborator: DJ Tikka Masala

Student Artists: Caeden, Fatina, Matthew, Bella, Rehena, Romero, Zayair, Ana, Amaury, Penelope, Caterina, Romelia, Tayler, Serena, Aden, and Timmy

*This season, we are serving sodas made from the nettle plant

Many thanks to all those who have supported this work. Thanks to our canner, Mike Lockwood of Duality Brewing. Cans will be donated to Trash For Peace, who builds community-led and equitable waste reduction and recycling systems in Portland. Thanks to artists Michael Bernard Stevenson, Lisa Jarrett, Harrell Fletcher, Lucia Monge, Lillyanne Pham, Luz Blumenfeld, Mo Geiger, Becca Kauffman, and Hilary Rappaport.

| Time | Program | People | Where | Type |

| 4:00PM – 4:50PM | Closing Event | PSU Art and Social Practice Program | TBA | Party/Celebration |

Letter from the Editors

Everyone you meet knows something you don’t. Part of doing an interview is learning things that you are curious about from experts and enthusiastic amateurs. Google searches don’t always give you the answers you may be looking for, as Jessica Cline tells Laura Glazer in their interview “How it Works to be Curious.” When sourcing through the web, “you don’t necessarily want to see the same image everyone else saw.” Asking people what they know or how they feel can give you a larger picture of what matters. An interview can be a tool to show that you care about someone. This is sort of like being a good host. Becca Kauffman talks with Fernando Perez in the interview “The Unexpected Host” about the intersection of hosting and interviewing, and how both require empathy and the ability to make people feel comfortable. “If you’re extremely empathic, that is reliably a good way to bring the best out of interview subjects,” says Perez.

As social practice artists we are regularly trying to create experiences for people as a form of art. In “Collaborative Curation, Ethical Exclusion, and the Materiality of Nightlife,” Luz Blumenfeld and Roya Amirsoleymani discuss how parties can be and are artworks: “I am frustrated by curatorial practices that simply display politics as content, signaling social justice values without living them, embedding them, operationalizing them, or building them into the ways in which a curatorial project or institution functions.” There are lots of reasons to conduct an interview. Sometimes it’s because you want to revisit a time in your life with someone who was there and find out if your memory matches theirs. Olivia Delgandio interviews her 2nd grade teacher about her teaching philosophies, a topic that may not have been on Olivia’s mind at seven, but is now a shared interest between the two. Sometimes an interview happens because you have someone in your life who is amazing at what they do and/or amazing at describing the world and you just want others to experience the person you have the privilege of having regular undocumented conversations with.

Reading interviews can make you feel like a backseat interviewer; you might wish different questions had been asked, or more time was spent on a particular idea. Remember, you can always conduct your own interview! Pursue a “self-educational” experience, explained in this issue by Harrell Fletcher in conversation with Kiara Walls. As we are so often reminded in our program, everyone you’re interested in is just a person, and you can always ask to talk to them. Go forth and interview! Here is some inspiration to get you started.

Caryn Aasness

Becca Kauffman

Emma Duehr Mitchell

Nice to Re-meet You

Caryn Aasness with Wesley Chung

“We’re always asking questions about information. ‘What did you do?’ The better question is, ‘What did it mean?'”

WESLEY CHUNG

I met Wesley Chung in the mid to late 2000s when I was a middle schooler and he was a youth mentor a bit older than me. He was the lead singer and songwriter of the indie pop collective, Boris Smile, at the time. Wesley recorded audio of various curated conversations from his life that sometimes made it into the music. Recently, as I reflected on my own artistic influences, I realized that my desire to ask people open-ended questions and document the answers was partly based on what I had seen Wesley doing in those years before I called myself an artist. I wanted to hear what he remembered about that time and how he would describe his own creative influences.

Caryn Aasness: I think a lot of the work that I’m interested in is just asking people questions. I started thinking about how, when I was in junior high, you were asking people questions that were interesting and recording their answers. And in my memory, I think you had a tape recorder.

Wesley Chung: It was a Dictaphone. Yeah.

Caryn: Okay. That’s what I was gonna ask, because I don’t know. What is it? What is a Dictaphone?

Wesley: It’s like an old fashioned thing. It has a small cassette, but it was for people to take notes or minutes. For lawyers, that’s what they use. It’s like the more grown up thing of the Talkboy FX, you know, from Home Alone 2. But the same idea, it’s just a simple recorder, but I like the sound of the tape. There’s a nice nostalgic sound to it.

Caryn: Where did you get the idea of using it for music?

Wesley: I think the band Bright Eyes would do some things where you hear some recording. I always like tracks where suddenly the curtain is lifted and you can hear the band talking a little bit. I think it was the band, The Books. That was the first time I stopped in my tracks at Fingerprints and I was just like, “Who is this?” Because it’s all field recordings— the sounds of footsteps, and then another recording of someone humming. Not in the way that hip hop would do that in a really creative way of turning it into the beat, which I also really like. I like sampling in hip hop and now when I think about it, probably the very first time I heard it was in what I think is one of the greatest albums of the 20th century, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill. If you listen to that album, there’s one song where at the end, they’re just in a classroom. It’s some older person asking kids questions like, “What do they think love is?” It’s this snapshot of a certain time. It feels very 90s but it could be any time. There’s no pretense to it, because it’s just whatever people said, whether it’s dumb or funny or profound. It’s kind of wildly exciting because you don’t know what people are gonna say. I was just like, so you’re human.

Caryn: And so then where did you get your Dictaphone?

Wesley: My dad had one. For the first album I did, I just randomly recorded people speaking and then put music underneath. By the second album, called Young and it Feels so Good, I was asking people questions that were kind of connected to the theme of the album: Why do you like being young?

Caryn: I remember.

Wesley: I was a young adult, working with young people, and it’s still close enough for me to remember the time and age and the awkwardness of that period of time. But I was just curious how different it was for people that were younger than me experiencing youth compared to myself. It ties to the theme of the album, just hearing young people’s voices. That album,, if I listened back to it, which I haven’t in a bit, will be a snapshot of my life and the people that I was around. I was spending so much time being a youth leader. It’s like old family movies or something like that. I think the question is broad enough to still be kind of interesting, and even talking about it now will make me want to listen back to it. What did people say? How different is it now?

Caryn: I think I was in middle school when that came out. There’s a song on the album about middle school that felt very real to me in the moment.

Wesley: Yeah. I think it’s rare to find the artists who are able to create a piece of work that’s still self-reflective enough both for themselves as well as the culture they’re living in.

Caryn: Do you have a favorite question to ask people?

Wesley: Well, I guess whatever question gets to what’s important. I’m always trying to figure out what people’s opinions are and what makes people tick. We’re always asking questions about information. Like, “What did you do?” “We did this.” But that’s only half. That’s like one aspect of it and it’s not the most important thing; it’s not what moves people. The better question is, “What did it mean? What did you do, and what did it mean?” It reveals a bit about that individual or maybe a bit about the community they’re a part of.

Caryn: You said before that you hadn’t listened to Young and it Feels so Good in a long time. How often do you go back to things that you’ve made in the past?

Wesley: Probably more often than other artists revisit their work. Some people are really shy, but like, to me, I made it for myself and for other people to enjoy. I have to listen back to stuff to go, does it still hold up? As I’m writing new work, sometimes I’ll reference back to stuff I’ve done previously and go, “Am I just repeating what I’m doing? Has it gotten a little bit better?” Because if I’m doing a song that’s quite similar to another song that I’ve done previously, that’s fine. That’s just called having a style. But if I’m not improving on it, or if I’m not getting closer to something that I find a bit more interesting or adding some twist to it, then I feel like I’m getting bored of my own songwriting.

Caryn: Do you currently have a tape recorder or Dictaphone now?

Wesley: Yeah, I’m using my phone a lot, but also something called a Zoom recorder. It’s digital and it’s much better for sound recordings. I have a recording of my nephew and my mom and me because we were trying to get this dog to howl and I just started recording it. And I used it for one of the tracks because I like the ending. It’s something just for me. I’m just like, that’s three generations of the Chung family all howling together, and the song title is “Rumspringa,” that idea of sowing your wild oats in the Amish community. So I like the idea that it’s the Chung wolf pack. There’s something that has all these layers of meaning for me, but for other people it might just be like, “Oh, that’s a cool sound.”

Caryn: Do you have the desire to share that information in any way with the listeners who want to dive deeper into it?

Wesley: No, but I guess that’s the way I approach albums and songs. If people want to dig deeper, oh there’s plenty. There’s plenty to find, but if people want to hear it just on the surface level then I just like to make sure that the melody is something that is pretty or it’s catchy, or something that people can enjoy from a lot of different angles.

Caryn: Do you have any final thoughts?

Wesley: It’s nice to re-meet you again as an adult. We’re so much further on in our lives. It’s just really cool, what you’re doing. I think that’s a great place, the intersection of art and how it reaches out of gallery spaces. That’s more punk rock.

Caryn: Yeah! More punk rock, that’s the goal!

Caryn Aasness: (They/them) is a Social Practice artist living in Portland Oregon. Originally from Long Beach California. When they were in middle school and Wesley asked why they liked being young, they said “You can move faster.”

Wesley Chung: (He/him) is a songwriter and musician living in Scotland now with his family. Wesley works at Flourish House, which is part of the Clubhouse movement that aims to support people living with mental illness outside of a medical model. He also writes and records music as a solo artist as A. Wesley Chung. You can check out his music here and here and here.

Touch the Things, Make the Sounds

“I would love to have that integration of classroom space, studio space, and library space all in one. And that might be like a completely difficult thing to realize, but I think that I always want the library everywhere.”

ELSA LOFTIS

During my first year in the MFA program, I tried using an art studio on campus. I filled it with my favorite supplies, inspiring books, and uncluttered surfaces. But when I was there, it did not feel vital to my practice. I relocated it to another room with a huge window, hoping that it would be invigorating to see activity outside. Instead, the studio remained quiet and lonely, with few opportunities to respond to the place.

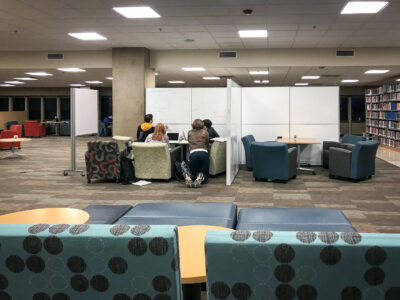

When Elsa and I talked for this interview, I was captivated by her vision of including spaces for art studios in the library, and I imagined relocating my under-utilized studio there. But even in my daydream, it still wasn’t a place I wanted to go. So, I started constructing a version of what a studio in the library might look like for me as a socially engaged artist: no walls, doors, or desks. Instead, there is a large table near the existing library study carrels and stools on wheels tucked under it. Nice paper and pens are available for free, and a special stapler for making zines is nearby. And anyone using the library is invited to sit down and work there. When we need inspiration or have questions, we can explore the books in the stacks and collaborate with Elsa.

This vision of a public art studio reveals an evolution of my creative practice, going from creating a private space that didn’t feel right, to envisioning a public space like the library as a studio space, and shaping it to respond to that site. This ideal place is not a space where I work in isolation. Rather, it is a large desk with space for me and other people to work, study, and create together; it is a place to be social in public.

Laura Glazer: I was trying to figure out a good place to start and what came to mind was how I’m haunted by something you said in our conversation last August. I have this really clear vision of what you described at OCAC(1), where you would have a pot of coffee and students would come in all the time. But at PSU, you were saying it doesn’t work at this scale. And you said, “I need help inserting myself into their practices.” Where are you with thinking about that?

Elsa Loftis: You know, I always feel re-invigorated when I’m able to do the instruction sessions because that’s when I start to get contacted by students. You know, when I get in front of them, and I do my little dog and pony show: here are the databases and this is why they’re so useful and look at all of the fun things you can look for and find. And then I will get emails after that from students who say, “oh, you visited my class and I’m doing this.” Then I get excited about the actual connection between working with people who are seeking information and hopefully assisting. And that’s the person-to-person stuff that I really enjoy. And that’s difficult because I’m waiting for people to kinda come to me. Whereas I would like to just sort of be out wandering around and saying, “Oh,” you know, “how are you today?”

I think very much about the library as place. The library is symbolic in many ways of a place for information. It’s a place to have solace and quiet and reflection, but there’s also kind of this element of, it’s a place to be. It’s a brick and mortar building and that is more or less important now than it ever has been.

I guess what I’m trying to say is, the library is definitely more than just what’s inside the four walls, it’s absolutely more than that. Not only because of our electronic resources and things of that matter, but it’s also kind of a headspace. It’s sort of a way to think, reflect, and work. But it’s also just the actual challenges of the proximity of where I am; in my past lives in other libraries, my office was sort of right out there where students were running around. So, if someone had a confused look on their face, I could just intercept them at their point of need. And where I am now, my office is in the cataloging and acquisitions space, which is behind locked doors so I have to actually physically leave my office to go look for students.

So that’s just a way that the space is elemental. And just having the energy of the people around me when they’re in their seeking phase of their research.

Laura: What does it mean to be an academic librarian?

Elsa: It’s a good question. It just means I’m a librarian in an academic setting. I’ve worked as a public librarian before, so that was a different experience. I mean, it’s not that different in a lot of ways. It’s a service orientation and you’re a public servant, you are meeting different needs in different spaces so you adjust your pedagogy or your workflow. You certainly are dealing with different kinds of collections. The range of people that you meet is certainly a little more narrowly defined in an academic library setting. Although most of the time we’re open to the public. Although we aren’t currently open to the public because of the pandemic. But we do offer spaces for the public to come in and share our resources and share our space. The PSU motto is “Let knowledge serve the city,” so we take that very seriously. We have that as an important role that we play, to offer information and services to people that are beyond our community.

And we also are a government document repository library. People need access to their government information and we provide that.

Laura: Where is the ideal space for you to work in? And it can be in a magical world!

Elsa: I think that in my magical world, the library is in the center of campus, in the heart of the physical space that students inhabit. I would love for there to be studio space in the library. In fact, I used to experiment with some of that.

I would try to put small little pop-up library collections in the studio spaces so that people could have reference resources while they’re throwing pots or welding things. [Laughs!] And when we did that, it was difficult to gauge the engagement with the resources, because a lot of times there’s no way to really track usage if it was just sort of like, Here’s some stuff you could look at it, you know, go nuts.

When you’re trying to work with students and getting folks to get engaged with your materials, you just throw stuff against the wall and see what sticks. We used to do those little pop-up libraries—these little mini curated things—and I thought that was really nice; I wanted people to be able to have access where they were. Not have to be like, Now I’d like to venture over to the library and look at some different examples of what I might be thinking about doing right now as I’m sitting here in the studio.

I would love to have that integration of classroom, studio, and library space all in one. And that might be a completely difficult thing to realize but I think that I always want the library everywhere. [Laughs]

Laura: That is a beautiful quote! “I want the library everywhere all the time.”

Elsa: Well, because I want people to feel like they own it. I think that libraries can be daunting spaces. When I talk about the library as “place,” that’s often very loaded, I think, for some people. I think of libraries as sanctuaries and places to explore and places to go on these adventures. And I think that maybe not everybody feels that way. I think that sometimes they can be sort of vaunted spaces. They’re sort of cold and quiet and maybe you don’t feel like you belong. If there’s one thing I want is for students to have agency over their library, because it is their library.

Elsa continued: We’re not here for any other reasons; we’re here for service. You want to humanize it, familiarize it and make it feel like their workspace, not as some sort of museum or a place where they aren’t supposed to touch the things or make sounds. That can be loaded in a way because I think the library as place is very important and I think that research can be done in so many different environments and formats. You can do a lot of research online; people are very good at doing research online. We’ve spent a lot of time here creating a lot of learning objects(2)(3) and ways that you can access materials virtually, and you don’t have to be in the library, but I also think that the space is important.

And again, that really depends on what kind of learner you are and how you like to interface with things. But I think one of the nice things, and especially for art students and art practice students, is that element of research that’s that really kind of almost haptic practice of research, like you get in there and you’re engaging with physical materials.

For some learners that’s really a big element for their practice, for their understanding: how you process things—physically and mentally—and work that into your creative practice.

And then there’s also that kind of iterative feeling of being in the lobby. You start… it’s like you search and you research, there’s this cycle. It’s not just searching, it’s re-searching. You keep coming back, you keep doing it again. And for some makers, it’s that kind of repetition.t’s that iterative process of research and it being a discipline, you approach it in a disciplined way. And that’s evidenced in a lot of different, physical practices of making art, too.

That’s what I also like to relate to people, is that the parts of the brain that you’re using when you’re doing research are creative parts of your brain. It’s part of art practice, too. You’re using those same kinds of problem solving connectors, the same little parts of your brain light up when you’re doing research as when you’re creating things. And I think that that’s a really useful way to look at it because it’s creative problem solving, just like you’re doing when you’re making work.

Laura: Where do you land on reframing the concept of research for a studio artist and a non-studio artist like myself?

Elsa: Well, it’s a really good question and it’s a really important issue. I think that all over the academy, not just in the arts, we are asking ourselves these questions and mostly from the library’s perspective: what do we collect and what voices are being centered; what voices are being left out; who is considered an expert in their field; what’s considered scholarship?

There are a lot of silenced voices in that narrow definition of what constitutes scholarly research and those definitions are opening up. We see this now and it’s our job as the library to be on the front lines of that and leading that, and collecting and valuing and centering—I don’t want to say alternative research, or maybe just non-traditional resources, I suppose—narrative things and people with learned experience and lived experiences, being thought of as experts, not necessarily attaining some sort of degree that makes them all of a sudden worthy to hear and listen to.

So, for a studio artist and a non-studio artist, I think that those paths are somewhat parallel. But it’s also difficult to wedge that into a traditional expression of scholarship. If you were doing a research essay and you needed five peer reviewed sources or X amount of primary sources versus secondary sources, and this is how you format your bibliography, it can be a little bit daunting to put this sort of non-traditional research into a traditional kind of scholarly product. I think that our instructors are more open than ever to that. You could speak to that better than I could. Do you feel that that is something that’s encouraged or at least tolerated?

Laura: I don’t know yet. I’m really taking my first class outside of the School of Art and Design this term in the History Department where I’m taking a class on museums and memory. We have to write a research paper, which I haven’t done since the nineties. [Laughs] So I am looking at the list of requirements, like six primary, secondary sources and thinking, huh, how can I bring the lens that’s relevant to me as an artistic researcher to this requirement? And I’m in a pretty good dialogue with the instructor. I want to be careful not to push her too far because I think she’s more traditional in how she approaches research papers and so are my classmates, but that doesn’t really work for me cause that’s not what I want to produce. I guess in undergrad, it was very traditional, very structured and I just didn’t do it.

Elsa: Well, you’re not alone in that. I think that we hear that a lot more and I think that that’s becoming more accepted. It’s not like, Oh, well, this student just doesn’t want to produce what I want them to produce. Even my son—he’s nine years old—his teachers are talking about, Okay, maybe you could make a video, maybe you could do a presentation rather than a paper or something like that, just being more inclusive to people with different learning styles or different storytelling. That’s been really central to a lot of more evolving scholarship, talking about things in terms of storytelling.

Laura: Definitely, which I’m always excited by and that’s the route I’m taking for my museums and memory research paper.

Would it make sense for a student to think of a librarian as a collaborator?

Elsa: Oh, yes. I hope so! [Laughs] Yes, because that’s how I think of myself. I think about myself as playing a supporting role. I love the idea of the librarian as a collaborator, yes. What that looks like in practice is a very interesting question, it can take a lot of forms. We’re in these roles as faculty, but we can do research together.

One of the things that I’m always trying to get to the root of is, how is that being engaged with, or is it being engaged with? And what can I do to better my pedagogy and my skills to share these research methods and these research resources and how can I do that better? I’m always, in a way, collaborating with students, whether they know it or not, to see how that’s going. Whether or not it’s a measurable outcome depends on how it’s being measured, I suppose. There’s traditional metrics of, We could give a pre-test and a post-test, or I can analyze people’s bibliographies to see if they found great sources or things like that, which is not really an active collaboration.

So, I’ve done things in the past where I’ve done focus groups with students, had them come to the library, tell me about what their needs are that we’re not meeting. What are we doing well? What could be improved? And again, trying to lend the agency to the students so that they have an active hand in creating their space, their library.

I’d love to collaborate with students on their independent projects, I think that would be wonderful. But mostly from my side, I am interested in collaborating with students to create a better library for them and a better learning experience for them. But I think it could happen on both sides.

Laura: When you say create a better library… I’ll tell you the vision that is in my head and it’s narrow: I think, Oh, get different books, more books.

Elsa: Okay.

Laura: Tell me what it means to you?

Elsa: It means community. I think it means an inclusive place where people feel welcome and where they feel productive. New books are nice but it’s also about active space and active engagement. There’s a few different ways to think about it.

More books, beautiful environments. Certainly, it’s nice if the chairs are comfortable and the colors are pleasing to the eye. But yeah, obviously the resources, the best possible resources that reflect our students’ needs and their interests, really inspire them and encourage their own growth.

Sure, the best possible library would be: you walk to a shelf and the thing that you were hoping for just pops right out. But what also is even better is that that thing didn’t pop out, but you got this other idea because the thing that was shelved next to it was sort of interesting. And so you pulled that out, and then you started walking around, you know what I mean? I love the serendipitous browsing, which is why we kind of create these cataloging systems where everything’s co-located.(4) So if you’re on the right track, you’re kind of on the right track. Sometimes that’s not true. Sometimes you gotta go to a whole different floor of the library if you want painting, but now you’re interested in aesthetics where you have to go down to the basement.

But that’s just the nature of the size of the collection, which is wonderful. You want a big, rich collection with lots of different formats and things kind of jump out at you in different ways. If you have the special collections, zines or ephemera or things like that, it’s just fun to kind of go through that stuff and get ideas. And then if you’re in the stacks, you’re kind of looking through the physical spines of the books and sort of getting the smell and all the physical and psychological cues that go with just sort of roaming around the stacks and having those kinds of serendipitous experiences. That would be the perfect library, I suppose.

And then you’d have a relaxing place to be, or where you were stimulated by all the cool stuff that was going on around you, where people were discussing great ideas. And then you’d have your studio right there and you could just go in and start working. That’d be pretty nice. Coffee wouldn’t hurt! [Laughs]

Laura: As a sidebar, I recently had that serendipitous experience at the downtown Multnomah County library and it was so special. I had to work for it, had to really pay attention to my inner voice, leading me around. It was triumphant and it changed my research path.

Elsa: Wow.

Laura: I’ve had that happen a little bit at the PSU library. It’s only been open for a little while, so I’m still finding my bearings there. So as you’re describing this magical library experience, the perfect library experience, I’m thinking of the different elements: in one way, you’re describing (in my mind), like a coffee shop and sometimes there’s a lot of activity and sometimes it’s really chill, without a lot of activity. And then I’m imagining a research lab for a scientist, like things bubbling over. It’s a really dynamic space, what you just described.

Elsa: I think the best libraries are, and it fits with our mission. But I also think that part of our other mission, just as important, is to collect and preserve. I mean it’s really important that we are keeping the human record, right? And that’s what we do. I think that a lot of what we do that is important, is curating a collection that is valuable and instructive to our students and also to the community at large.

And so we need to be very intentional about how we use our resources to provide those things. Resources are limited and not just in terms of budgets, but also in terms of space and our priorities and what we can provide. And that’s where librarians come in and use their expertise to get the best, most relevant information in front of a searcher– a researcher.

Laura: What’s informing you as a librarian, right now?

Elsa: In terms of what to collect or in terms of just how I’m spending my time?

Laura: Referring to how you collect, because you were just talking about that, the intentionality of a librarian. So that leads me to wonder: well, what’s informing your intentionality?

Elsa: We need to be responsive to the needs of our departmental faculty. So, of course instructors and professors will be telling us what they need to support their curriculum.

Another good indicator for me is when new courses come up, we are asked to write a statement of support from the library, so I get to see syllabi and make sure that our collections can support the teaching and learning endeavors of the new classes that are starting. So, that’s really wonderful for me because then I can see what’s being assigned. Certainly, I’m looking at making sure that we can support the assigned reading lists, but also just kind of getting a sense of where things are going in the departments. And so that is really informative to me.

It’s also informative to me when I’m in my instruction sessions, because I have an idea of what the assignments are, the research projects, working with students, finding out what they’re interested in and then that leads me to kind of explore. And maybe we don’t have everything that they might need and that’s when I go and I find it.

I also read a lot of academic book reviews, new things coming out by certain publishers that I really value or appreciate, but I’m also still looking for things that aren’t as well represented in our collection. We need to have a sense of where the gaps in our collection are, what might be overrepresented or underrepresented. Do we need another book about Renaissance painting, or are we more interested in collecting a new exhibition catalog about yarn bombing? I don’t know. [Laughs] It doesn’t mean that the other one isn’t useful and necessary. But where do we fit in the conversation and are we representing what’s going on currently in our students’ practice mostly and what’s being taught in the curriculum.

The other consideration we have is we are part of this wonderful big consortium. We have 37 other libraries from universities and colleges in our area that also have their collections and we share that catalog. So, we call that cooperative collections development.

While I might not need to buy everything… I can’t buy everything. But the University of Washington might have one and Portland Community College might have one. Reed College might have one. Willamette University just acquired PNCA (Pacific Northwest College of Art) and now their library collection is part of our catalog. They have some really amazing parts of their collection that might not be represented in the PSU collection, but I can get it.

So those are other things that are kind of informing my collection development and what I see as a need for our library. As wonderful as it is to have all the things on the shelves in the library space, where you’re looking and searching and having those serendipitous shelf moments, there’s no way that we can have everything on the shelf right in front of you. So that can be a frustration. People like to just go and browse and that’s awesome, I get that. But there’s so much more to our collections. They’re all over the region, they’re all over the world, and they’re in the online environment. And so some of those things do get missed when you have a researcher who just really likes to browse the shelves.

Laura: I read your article, The More Things Change: The Collaborative Art Library, and I’m a huge fan of the inclusion of “collaboration” in the keyword list. But I want to back up a little bit and ask you, does PSU have an art library and actually what is an art library?

Elsa: Ah, that’s a really good question. We have our central library; we don’t have any sort of satellite library. Some departments have their own collections, but they aren’t under the purview of the library.

But an art library you are basically focused on art but it’s not to the exclusion of everything else. I’ve worked in art libraries and it’s mostly to support a specific kind of learning activity, the study of art in this case. Museum libraries are much the same, they’re there to support the research of the curators or visiting researchers who come in and would exemplify a kind of collection focus that a museum has. The Museum of Modern Craft, when it was around, had its own library and those had obviously a very specific scope and focus.

At the OCAC library, we definitely built our collection around what was being taught in school, so the different kinds of craft concentrations, but also art history. And there was a lot of social history too, you know? Libraries take many forms and many shapes and the art library is not a monolith of one kind, but you would certainly find more art books in it. [Laughs]

Laura: Thinking about the art library: so PSU’s collection isn’t considered an art library?

Elsa: Well, it would be the art section of the library. Yeah, yeah, yeah, absolutely.

Laura: Okay. Got it. Cause as I was reading the article, I was like: oh no, are we not included?

Elsa: Oh my gosh, no, no, of course not. We have wonderful, wonderful art in our library. And I mean, an art library can be conflated to mean so many things. It could be a library of art, it could be a bunch of paintings lined up. A library is terminology that can mean any kind of collection, I suppose, as long as it’s organized and preserved in some way.

We use the Library of Congress classification system so most of our art books are in the Ns and they’re sort of located in a way that’s find-able and together. But other parts of “art” are not in the Ns necessarily. They might be in more technology-related things. So like photography will be in the Ts and aesthetics and the study of beauty and things like that are going to be in the Bs, which is more in the philosophy area.

That’s what’s wonderful about the multi-disciplinary part of that, and you can look all over the collection and that can inform your art practice, certainly.

Laura: When you think about yourself as a collaborator with a student researcher, what do you make together and what do you wish you could make together? We talked about maybe a bibliography, but what are some other things? I’m trying to really wrap my head around what that collaboration is like with you as a librarian or even with the library as space?

Elsa: Well, I think that one thing that was fun that I’ve done in the past with students at the Oregon College of Art and Craft Library has been for a guest student to curate a book display which was always really fun. We have had students do that in the past where they go with the theme and find things that they’ve connected with and arrange it in a way that’s pleasing or just accessible for people.

We’ve had people do art shows in the library, certainly utilizing not only the space, but also elements of the stacks and the books themselves. One example of that is, I had a student that made all of these really delicate ceramic books and he would kind of inner-shelve them in the space and it was really neat. We had students take over the space in a lot of different ways with their physical work.

Then rearranging the library space to facilitate other kinds of making and doing and even if it’s something as simple as having a knitting circle going on in the library and we would pick topics to talk about as we were doing that, readings that we all might have done, or just sharing favorite stories or something like that. I suppose you could mean a collaboration in that way. Students collaborating with the librarian themselves or with the space or just the different ideas of use.

We had one student one time who was exploring repetitive practice stuff and she put a big trampoline outside the library and she would go and be on the trampoline for at least two hours a day, not jumping necessarily, but she would be sitting out there or just being in that little space. That was outside of the library and certainly everybody else was welcome to use it, [laughs] and it was just kind of this fixture. It wasn’t necessarily anything that I was doing or collaborating with myself or even the space of the library, but it did take on a form of its own because it was this sort of feature that was happening and people would talk about it and she would start to try to help generate those conversations, too, because that was part of her inquiry.

I prefer the ones where the space is being used, reused, and remixed and the collection is part of that. And anything that people are using to connect. That’s what I hope for when I collaborate with students or have them collaborate with the space or the collection.

Laura: Anything being used to connect ideas? People?

Elsa: Yeah.

Laura: What are you meaning with that connection?

Elsa: I mean specifically people. Again, having ownership of the library, having agency, and feeling like they belong there and that the library can change to support them rather than the other way around, if that makes sense. Because when you come into the library space, you have to kind of conform to it in a way, right? You need to position yourself where you need to find the things and there are rules: you have to go to the circulation desk, you have a checkout period, you have a loan period. So there’s sort of these other things. But I think that the library can also transform and be a space that can be used and enjoyed and people can connect.

A really great example of our collaboration was with that subject guide that we created.

Laura: Yes!

Elsa: That can be a work in progress and it can be molded and shaped. That kind of learning object is really wonderful because I think that it fits a need and it wasn’t a need that I knew about until you told me.

That was a great example of a collaboration. It’s a positive step that now exists and it’s something that can continue to change and be added to. There’s a lot more things like that that we can do, I think, that I’d love to see students engage with and make it their own, in a way. I can’t exactly let everybody edit that guide, but I can garner all kinds of input and feedback about it and adapt and change and be agile enough to create new things out of it.

Laura: You mentioned including things in the collection that maybe aren’t in the traditional way we think of a collection being developed. And one example that comes to mind is publications by artists. How do you see those fitting into an academic library?

Elsa: You don’t mean like a monograph, you mean like kind of ephemera or like zines or…cause that can take so many different shapes.

Laura: I think zines are a good example. I’m also thinking about small press publications, things published that aren’t easy for an institution to buy.

Elsa: Right, right. Absolutely. Well, it gets challenging. We have the usual constraints of where to get it and how to collect it comprehensively, I suppose. And so it’s helpful if you wanted to have a concentration of some kind, like artists from Portland, for example, or an artist working in a specific kind of thematic area or medium or something like that. I suppose if we were to kind of pinpoint that sort of thing then it’s a little bit more scoped rather than just like, oh, you know, kind of anything we come across, we get.

Our special collection is a good place for some of this stuff, especially when the formats are a little unstable. Case in point, with a zine, I couldn’t really throw that on the shelf, it would get kind of destroyed, right? There needs to be a special place. And digitization of that kind of thing. Then that can go in our institutional repository, like PDXScholar, if it was somebody from our community, that would make a lot of sense. So there’s room for that and it tends to be kind of in what we think of as our special collections. Just for its own kind of protection, just physically, so it doesn’t fall apart.

Some libraries have very specific collections based on that. You know, ephemera collections, and postcard collections, for goodness sake! The New York Public Library has an amazing historical menus collection and things like that, it’s wonderful. It goes library by library and a lot of that has to do with the institution that it’s supporting.

Laura: I saw there was a faculty announcement that you are an associate professor.

Elsa: Oh no, I’m an assistant professor assistant. I haven’t gotten tenure yet.

Laura: Sorry, I mix them up. Do you teach classes?

Elsa: Librarians have faculty status at Portland State, or they can. We have faculty status and so we do teach, but teaching is defined as provision of library services. So our kind of pedagogy is providing information. We do teach, I teach instruction sessions. It’s kind of defined as, provision of library services is what teaching is, which means that we are providing the ability to do the research; that is our process.

Well, how is this going to look? What is the theme of this journal?

Laura: There is no theme for this issue. I bring the theme. For me, my practice is about books, collections of knowledge, selecting pieces of knowledge, libraries as spaces, people as collaborators. When we talked in August, I was like: oh, Elsa is a great resource. I need to understand more about what you do.

There’s a woman in Montana who does a traveling bookstore. And she goes all over the country and she comes to Portland. So I’m thinking about interviewing her in the winter. Kind of along this theme of books as spreaders of knowledge and trying to figure out where do I fit? Why is that a part of my practice? So, that’s why I’m talking with you. I’m like, why am I so drawn to the library, books, and collecting?

Elsa: I love that idea of the traveling bookseller, that’s really neat.

I had a colleague at OCAC, she’s at Reed now, she’s a book artist, Barbara Tetenbaum. And she was doing this really cool project where it was called The Slow Read and she was using Willa Cather’s book My Ántonia and she had these display monitors up in various places, and in different cities, too.

It would be just a display of one page of the book. And so people could kind of come and read that page. And then the next day there would be a new page. The idea was sort of like this community read, but also really slowly.

Laura: At the library?

Elsa: We had one of the monitors up at the library. But she went out all over the place and it was centered in Nebraska, because that’s where the author was from.

Laura: And she’s at Reed College now?

Elsa: Yeah. She and I used to teach together and she’s wonderful.

Laura: I’m looking at the website right now.

Elsa: Oh yeah, you got it? Okay, great. That puts me in mind of what you’re talking about, right?

Laura: Yes!

Elsa: Yeah. Pretty neat, huh?

Laura: Oh, my goodness. Where did you teach with her?

Elsa: At OCAC. She was the chair of the Book Arts department. Yeah, and then she and I co-taught a student success class for incoming freshmen. It was basically like a college skills class. I think we called it College Skills or something like that. But it was me teaching research and then also just how to be a student and how to succeed in school and even like financial literacy and stuff like that.

So she and I became good friends because we designed the whole course together and she was in the middle of this whole project in the last year that I was there and I was so blown away. You know, talk about collaborative and text as experience, right?

Laura: Oh my gosh. Text as experience. Did you just make that up?

Elsa: I just made that up and I don’t know, [laughs] maybe it flew in from somewhere. She’s one of those people that’s really quite amazing.

Laura: I’m going to have to spend some time with this. See, I already benefited from talking with you! I would not have known, oh my gosh!

This issue of SOFA Journal won’t come out until mid December, I think. And I will keep you in the loop. And just so you know, I personally publish it as a printed zine. And lucky you, you’ll be a lifetime subscriber. So you’ll get a copy of every one that I do in the next year and a half. And then I’ll also send you the back issues.

Elsa: Well, they’re beautiful. I’ve been looking at them on PDXScholar. I’ve never seen a physical one, but I’ve been enjoying looking at them, they’re so rich and pictorial.

Laura: Awesome. Thank you so much for your time.

Elsa: Have a wonderful weekend!

Laura: Thank you! Bye!

Footnotes:

(1) Oregon College of Art and Craft was a private art college in Portland, Oregon, from 1907 until 2019 when it terminated all of its degree programs.

(2) A learning object is a digital, open educational resource that is created to assist in a learning event. M, Vanessa, and Jane C. “What Are Learning Objects?” Instructional Resources, October 15, 2021. https://blog.citl.mun.ca/instructionalresources/what-are-learning-objects/.

(3) From Elsa: “I was specifically talking about the Library Guides and from our website, Subject, Course, and How to Guides, which are created by Portland State librarians to help you! These guides provide helpful resources, strategies for research, and tutorials.”

(4) Co-located means having multiple things located together—like the sections in a library—the painting books are near the other painting books, Portuguese language books are next to the other Portuguese language books, and so on. Definition provided by Elsa Loftis.

Laura Glazer (she/her) is a student in the Art and Social Practice MFA program at Portland State University. She graduated from Rochester Institute of Technology with a BFA degree in photography and lives in Portland, Oregon. Her curiosity about people and the visible world guide her as she uses research, conversations, and collaboration to create projects. She processes and organizes research through publications and local, free distribution methods of printed matter and visual culture such as brochures, flyers, and postcards. See her projects and process notes on lauraglazer.com and Instagram.

Elsa Loftis (she/her) joined the Portland State University library faculty in 2018 as the Humanities and Acquisitions Librarian. She is the subject liaison to the College of Art + Design, and the Film Studies, World Languages, and Literature departments. Prior to her arrival at PSU, she was the Director of Library Services for the Oregon College of Art and Craft, worked as the librarian for Everest College, held positions at the Brooklyn Public Library, the Brooklyn Museum Library and Archives, and the Pratt Institute Library. She received her MLIS from the Pratt Institute, and her BA in International Studies at the University of Oregon.

Healing in Practice

“I think about joy being something that doesn’t come from the outside and joy is not something that we assume is permanent. It’s something that we are trying to be aware of. I think that recognizing that the possibility for joy exists within me changes my focus. Because I’m looking less directly at how I can succeed, how can I win? I think that’s a really useful way to think about it.”

DARRELL GRANT

The Black Box Conversation Series (BBCS) is a podcast and radio project launched in 2020 in response to the pandemic. BBCS aims to create a safe space where people of color can hold meaningful conversations centered around their human experience. My practice often uses conversations and storytelling as primary tools to connect us. I’m interested in co-authoring work that centers the need for reparations to address the injuries inflicted on the African American community. For SoFa journal, I’m sharing a conversation about healing with PSU jazz professor and composer, Darrell Grant. This interview originally aired on Portland State University’s radio station, KPSU, on November 11, 2021.

Kiara Walls: Hello everyone, my name is Kiara Walls and this is the Black Box Conversation Series. The Black Box Conversation Series aims to create a safe space where people of color can hold meaningful conversations centered around their human experience. Today, I will be speaking with professor Darrell Grant, and we will be talking about healing. So to kick things off, I will let Darryl introduce himself and then we’ll go into some of the questions.

Darrell Grant: I’m Darrell Grant. I’m a jazz pianist, composer, and a professor of music at Portland State University where I’m entering my 25th year of teaching. I’m also associate director of the School of Music and Theater at PSU. I direct a new program in the College of the Arts, it’s called the Artist as Citizen Initiative, which is an interdisciplinary pathway/intersection between the arts and social justice.

Kiara: Awesome. I’m super excited to be talking with you today. We’ll just jump right in. The first question is, what does healing feel and look like to you?

Darrell Wow, well, let’s start with the easy question. The first thing that I think of is self-knowledge, because I think without that, it’s really difficult to approach the idea of healing. Self-knowledge, for me, has meant coming to understand myself as a Black person, coming to appreciate the unique experiences that I have had, and both the challenges and the successes. I think then coming to see that it’s okay for me to be uniquely myself, both, you know, as an individual, but especially as a Black person in America. That has been a big part of the healing is, you know, self knowledge and then self acceptance. After that comes the process of sort of working through all the things that come up, trying to find contentment and satisfaction. I mean, happiness is kind of a big ask. It’s something that comes and goes, but I’m feeling like this way of feeling content, you know, sort of content with my lot in life, with my path in life. So those are the kinds of things I think about when I think about healing.

Kiara: Thank you for that. I just want to touch back on how you’re talking about being content versus being happy, because happiness is fleeting. There’s this idea that the main goal is just to be happy, and happiness is an emotion that comes and goes. What I think about is joy, and being able to cultivate joy. It doesn’t necessarily have to be tied to anything that you’re working towards, but something like a framework that you create every single day. You find joy in the little specialties of life, you add value to that, versus something that’s external and also something that takes a certain amount of work to get towards. Then the idea is that you’ll be rewarded with feeling. In my opinion, healing is also tied to happiness. Before I had a better understanding of what healing was for me, I used to think that it was more about when you get to a certain point in your journey that you no longer deal with any bad things.

Darrell: Right! Like nothing goes wrong, it’s all good. You have finally crossed over!

Kiara: I’m just like, WOW, that’s a really tall order. I think it’s also not sustainable. I mean, to be human is to make mistakes.

Darrell: Yeah. It’s to be imperfect. I mean, that’s nature, you know, it’s really funny. I was just watching Oprah’s interview with Will Smith, and he has just written a new memoir where he talks a lot about this idea of joy. I know a lot of African Americans, especially artists in my field who are always aspiring, always reaching, always stretching, and always trying to get to someplace. On the outside, a lot of that looks like success. Some of it looks like security. I think about joy being something that doesn’t come from the outside and joy is not something that we assume is permanent. It’s something that we are trying to be aware of. I think that recognizing that the possibility for joy exists within me changes my focus. Because I’m looking less directly at how I can succeed, how can I win? I think that’s a really useful way to think about it.

Kiara: Right. It’s about giving yourself that agency to experience that feeling, you know, giving yourself that power versus always having external validation, because I feel like external validation is nice, but what happens when you don’t always have that type of energy around you? Not to say it doesn’t feel good when you get the external validation, but it’s not going to be a situation where it’s around you all the time.

Darrell: Or you wear yourself out constantly seeking it. That’s what I think is interesting hearing Will Smith talk about it in reflecting on that myself, that there’s this really interesting and insidious way where you keep chasing accomplishment. It’s never quite enough, you get it, but it’s not. It’s just, Oh, but if I could just get that, oh, this is nice, but if I could just get that one thing. I always thought I’m not really chasing money or I’m not chasing things that are considered vain. It looks like I’m really trying to do good things, right? But if I’m still seeking that validation, then I’m ignoring the times when I really need to be stopping and doing nothing, just sitting, just restoring myself for the thing that I’m really supposed to be doing, rather than doing this one other little thing to try and get the validation. I’ve noticed this act of chasing your tail a bit.

Kiara: That also makes me think about the energy that one puts into their work. When you aren’t chasing external validation, you’re truly creating the work because it’s coming from your heart and your soul. There’s a level of transparency and an organic element to it that is seen within the work.

Darrell: I don’t know though. I mean I hear what you’re saying, but I also feel like it won’t necessarily be perceived outside of yourself. Do you know what I mean? Because I think that one of the things that we get good at when we are seeking validation is, we get good at doing things that get the kind of recognition that we’re looking for. Right? And if you desire to be validated for being selfless, you get really good at doing work that is admired for being selfless. The problem is if you’re really supposed to be doing something else, like if your own path to joy or fulfillment involves something else, other people may not recognize that because you’re not hitting those buttons that they’re used to seeing. I think that as an artist, I find that especially true. It’s like, sometimes you really do have to go inside and when people ask you what you’re doing, you got nothing to show you can’t say to them I’m trying to figure some stuff out. I’m just working on some stuff. Because they’re like, “When are you going to play a show? What are you going to do?” And then I say, “I’m not sure because I’m really trying to work some stuff out.” This kind of dialogue does not get a lot of validation. So I think it can be lonely. So that’s when I think what you said about the joy, finding the joy and doing it for those reasons, is really necessary because it can be a dark lonely place sometimes.

Kiara: I totally understand. It’s funny because people can’t always see the work that you’re doing or the work that you’ve been up to and all of the things that you’re processing. So it just boils down to giving yourself that validation, and allowing yourself that space to process things and not be worried about what anyone else is saying or their expectations. With that said, what are the expectations that you have for yourself? Can you meet those expectations and call it a day? Can you describe any day-to-day rituals you practice that contribute to your self-care?